Objectives

• Identify the components of a neurological history.

• Describe the five components of the neurological assessment.

• Discuss the neurological changes associated with intracranial hypertension.

• Identify key diagnostic procedures used in assessment of the patient with neurological dysfunction.

• Discuss the nursing management of a patient undergoing a neurological diagnostic procedure.

• Identify the different types of intracranial pressure monitoring devices.

![]()

Be sure to check out the bonus material, including free self-assessment exercises, on the Evolve web site at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Urden/priorities/.

Assessment of the critically ill patient with neurological dysfunction includes a review of the patient’s health history, a thorough physical examination, and an analysis of the patient’s laboratory data. Numerous invasive and noninvasive diagnostic procedures may be performed to assist in the identification of the patient’s disorder. This chapter focuses on clinical assessments, laboratory studies, and diagnostic procedures for the critically ill patient with a neurological dysfunction.

Clinical Assessment

A thorough clinical assessment of the patient with neurological dysfunction is imperative for the early identification and treatment of neurological disorders. The completed assessment is used for developing the management plan for the patient. The assessment process can be brief or can involve a detailed history and examination, depending on the nature and immediacy of the patient’s situation.

History

Neurological assessment encompasses a wide variety of applications and a multitude of techniques. This chapter focuses on the type of assessment performed in a critical care environment. Common to all neurological assessments is the need to obtain a comprehensive history of events preceding hospitalization. An adequate neurological history includes information about clinical manifestations, associated complaints, precipitating factors, progression, and familial occurrences. If the patient is incapable of providing this information, family members or significant others should be contacted as soon as possible. An ideal historian is able to provide detailed information with emphasis on the chronology of events. Valuable information is gained through medical history that assists the patient’s clinical assessment. When someone other than the patient is the source of the history, it should be an individual who was in contact with the patient on a daily basis. Frequently, valuable information is gained that directs the caregiver to focus on certain aspects of the patient’s clinical assessment.1

Physical Examination

Five major components make up the neurological evaluation of the critically ill patient. Nursing assessment priorities focus on evaluating (1) level of consciousness, (2) motor function, (3) pupillary function, (4) respiratory function, and (5) vital signs. A complete neurological examination requires assessment of all five components.1

Level of Consciousness

Assessment of the level of consciousness is the most important aspect of the neurological examination. In most situations, a patient’s level of consciousness deteriorates before any other neurological changes are noticed. These deteriorations often are subtle and must be monitored carefully. Nursing priorities in assessment of level of consciousness focus on (1) evaluating arousal or alertness and (2) appraising consciousness or awareness.1 Although universally accepted definitions for various levels of consciousness do not exist, the categories outlined in Box 17-1 are often used to describe the patient’s level of consciousness.1–4

Evaluating Arousal

Assessment of the arousal component of consciousness is an evaluation of the reticular activating system and its connection with the thalamus and the cerebral cortex. Arousal is the lowest level of consciousness, and observation centers on the patient’s ability to respond to verbal or noxious stimuli in an appropriate manner. To stimulate the patient, the nurse should begin with verbal stimuli in a normal tone. If the patient does not respond, the nurse should increase the stimuli by shouting at the patient. If the patient still does not respond, the nurse should further increase the stimuli by shaking the patient. Noxious stimuli should follow if previous attempts to arouse the patient are unsuccessful. To assess arousal, central stimulation should be used (Box 17-2).

Appraising Awareness

Content of consciousness is a higher-level function, and appraisal of awareness is concerned with assessment of the patient’s orientation to person, place, and time. Assessment of content of consciousness requires the patient to give appropriate answers to a variety of questions. Changes in the patient’s answers that indicate increasing degrees of confusion and disorientation may be the first sign of neurological deterioration.1,3,4

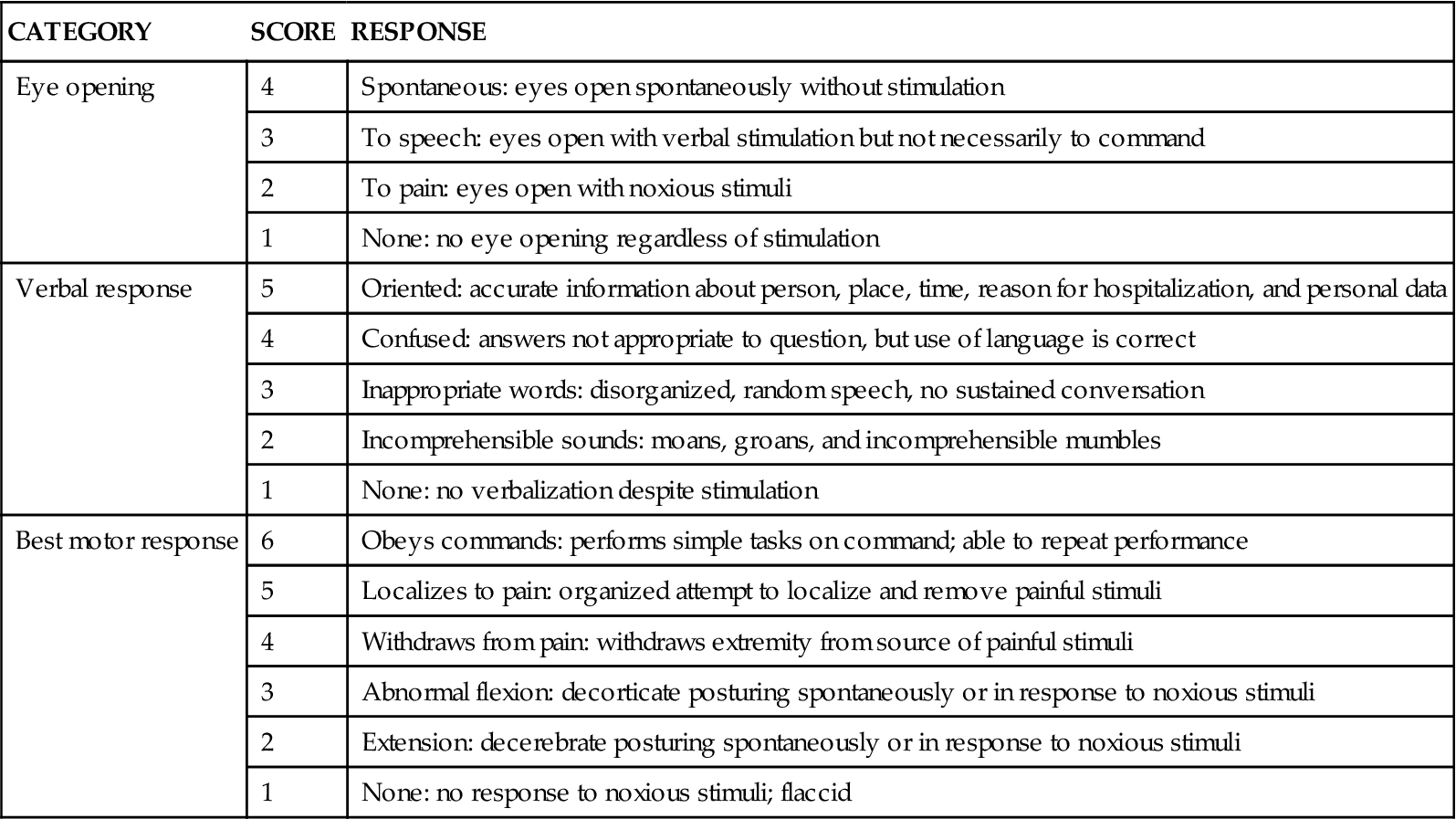

Glasgow Coma Scale

The most widely recognized level of consciousness assessment tool is the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS).5 This scored scale is based on evaluation of three categories: eye opening, verbal response, and best motor response (Table 17-1). The best possible score on the GCS is 15, and the lowest score is 3. A score of 8 or less on the GCS usually indicates coma. Originally, the scoring system was developed to assist in general communication concerning the severity of neurological injury. Recent testing of the GCS revealed a moderate to high agreement rating among physicians and nurses.6,7 Several points should be kept in mind when the GCS is used for serial assessment. It provides data about level of consciousness only, and it never should be considered a complete neurological examination. It is not a sensitive tool for evaluation of an altered sensorium, nor does it account for possible aphasia. The GCS is also a poor indicator of lateralization of neurological deterioration.7 Lateralization involves decreasing motor response on one side or unilateral changes in pupillary reaction.

TABLE 17-1

| CATEGORY | SCORE | RESPONSE |

| Eye opening | 4 | Spontaneous: eyes open spontaneously without stimulation |

| 3 | To speech: eyes open with verbal stimulation but not necessarily to command | |

| 2 | To pain: eyes open with noxious stimuli | |

| 1 | None: no eye opening regardless of stimulation | |

| Verbal response | 5 | Oriented: accurate information about person, place, time, reason for hospitalization, and personal data |

| 4 | Confused: answers not appropriate to question, but use of language is correct | |

| 3 | Inappropriate words: disorganized, random speech, no sustained conversation | |

| 2 | Incomprehensible sounds: moans, groans, and incomprehensible mumbles | |

| 1 | None: no verbalization despite stimulation | |

| Best motor response | 6 | Obeys commands: performs simple tasks on command; able to repeat performance |

| 5 | Localizes to pain: organized attempt to localize and remove painful stimuli | |

| 4 | Withdraws from pain: withdraws extremity from source of painful stimuli | |

| 3 | Abnormal flexion: decorticate posturing spontaneously or in response to noxious stimuli | |

| 2 | Extension: decerebrate posturing spontaneously or in response to noxious stimuli | |

| 1 | None: no response to noxious stimuli; flaccid |

Motor Function

Nursing priorities in assessment of motor function focus on (1) evaluating muscle size and tone and (2) estimating muscle strength. Each side should be assessed individually and then compared with the other.1,8

Evaluating Muscle Size and Tone

Initially, the muscles should be inspected for size and shape. The presence of atrophy is noted. Muscle tone is assessed by evaluating the opposition to passive movement. The patient is instructed to relax the extremity while the nurse performs passive range-of-motion movements and evaluates the degree of resistance. Muscle tone is appraised for signs of flaccidity (no resistance), hypotonia (little resistance), hypertonia (increased resistance), spasticity, or rigidity.8

Estimating Muscle Strength

Having the patient perform a number of movements against resistance assesses muscle strength. The strength of the movement is then graded on a 6-point scale (Box 17-3). Ask the patient to extend both arms with the palms turned upward and to hold that position with the eyes closed. If the patient has a weaker side, that arm will drift downward and pronate. The lower extremities are tested by asking the patient to push and pull the feet against resistance or to elevate the legs.9,10

Abnormal Motor Responses

If the patient is incapable of comprehending and following a simple command, noxious stimuli are necessary to determine motor responses. The stimulus is applied to each extremity separately to allow evaluation of individual extremity function. Peripheral stimulation is used to assess motor function (see Box 17-2).1,2 Motor responses elicited by noxious stimuli are interpreted differently from those elicited by voluntary demonstration. These responses may be classified as shown in Box 17-4.8

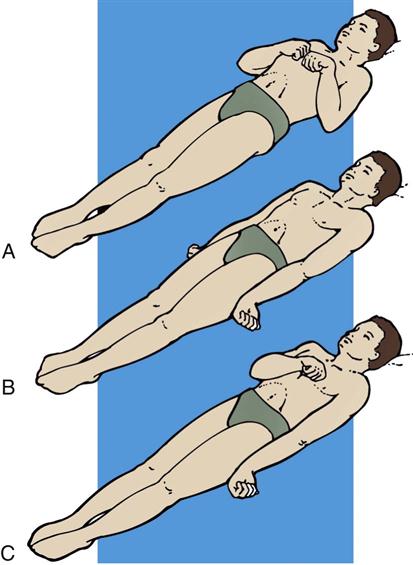

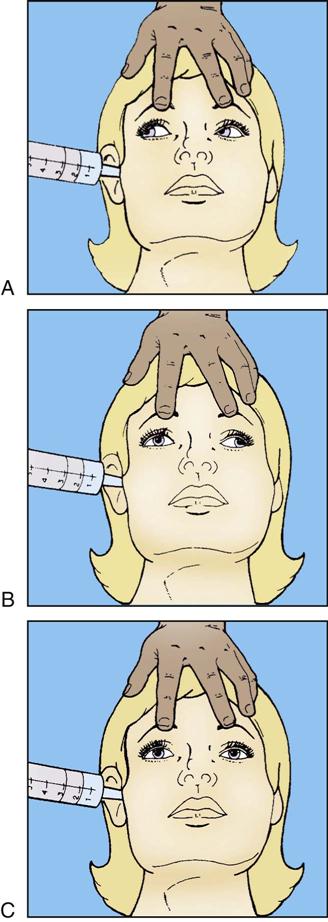

Abnormal flexion also is known as decorticate posturing (see Figure 17-1, A). In response to painful stimuli, the upper extremities exhibit flexion of the arm, wrist, and fingers with adduction of the limb. The lower extremity exhibits extension, internal rotation, and plantar flexion. Abnormal flexion occurs with lesions above the midbrain, located in the region of the thalamus or cerebral hemispheres. Abnormal extension also is known as decerebrate rigidity or posturing (see Figure 17-1, B); when the patient is stimulated, teeth clench, and the arms are stiffly extended, adducted, and hyperpronated. The legs are stiffly extended with plantar flexion of the feet. Abnormal extension occurs with lesions in the area of the brainstem. Because abnormal flexion and extension appear similar in the lower extremities, the upper extremities are used to determine the presence of these abnormal movements. It is possible for the patient to exhibit abnormal flexion on one side of the body and extension on the other (see Figure 17-1, C).1–3 Outcome studies indicate that abnormal flexion or decorticate posturing has a less serious prognosis than does extension, or decerebrate posturing. Onset of posturing or a change from abnormal flexion to abnormal extension requires immediate physician notification.3

Pupillary Function

Nursing priorities in assessment of pupillary function focus on (1) estimating pupil size and shape, (2) evaluating pupillary reaction to light, and (3) assessing eye movements. Pupillary function is an extension of the autonomic nervous system. Parasympathetic control of the pupil occurs through innervation of the oculomotor nerve (CN III), which exits from the brainstem in the midbrain area. When the parasympathetic fibers are stimulated, the pupil constricts. Sympathetic control originates in the hypothalamus and travels down the entire length of the brainstem. When the sympathetic fibers are stimulated, the pupil dilates. Pupillary changes provide a valuable assessment tool because of pathway locations. The oculomotor nerve lies at the junction of the midbrain and the tentorial notch. Any increase of pressure that exerts force down through the tentorial notch compresses the oculomotor nerve. Oculomotor nerve compression results in a dilated, nonreactive pupil. Sympathetic pathway disruption occurs with involvement in the brainstem. Loss of sympathetic control leads to pinpoint, nonreactive pupils. Control of eye movements occurs with interaction of three cranial nerves: oculomotor (CN III), trochlear (CN IV), and abducens (CN VI). The pathways for these cranial nerves provide integrated function through the internuclear pathway of the medial longitudinal fasciculus (MLF) located in the brainstem. The MLF provides coordination of eye movements with the vestibular nerve (CN VIII) and the reticular formation.3

Estimating Pupil Size and Shape

Pupil diameter should be documented in millimeters with the use of a pupil gauge to reduce the subjectivity of description. Most people have pupils of equal size, between 2 and 5 mm. A discrepancy up to 1 mm between the two pupils is normal; it is called anisocoria and occurs in 16% to 17% of the human population.11 Change or inequality in pupil size, especially in patients who previously have not shown this discrepancy, is a significant neurological sign. It may indicate impending danger of herniation and should be reported immediately. With the location of the oculomotor nerve (CN III) at the notch of the tentorium, pupil size and reactivity play a key role in the physical assessment of intracranial pressure (ICP) changes and herniation syndromes. In addition to CN III compression, changes in pupil size occur for other reasons. Large pupils can result from the instillation of cycloplegic agents, such as atropine or scopolamine, or can indicate extreme stress. Extremely small pupils can indicate opioid overdose, lower brainstem compression, or bilateral damage to the pons.11,12

Pupil shape is included in the assessment of pupils. Although the pupil is normally round, an irregularly shaped or oval pupil may be observed in patients who have undergone eye surgery. Initial stages of CN III compression from elevated ICP can cause the pupil to have an oval shape.1,11

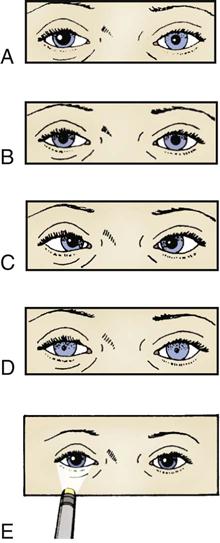

Evaluating Pupillary Reaction to Light

The pupillary light reflex depends on optic nerve (CN II) and oculomotor nerve (CN III) function (Figure 17-2).3,11 The technique for evaluation of the pupillary light response involves use of a narrow-beamed bright light shined into the pupil from the outer canthus of the eye. If the light is shined directly onto the pupil, glare or reflection of the light may prevent the assessor’s proper visualization. Pupillary reaction to light is identified as brisk, sluggish, or nonreactive or fixed.1 Each pupil should be evaluated for direct light response and for consensual response. The consensual pupillary response is constriction in response to a light shined into the opposite eye. This reflex occurs as a result of the crossing of nerve fibers at the optic chiasm.1 Evaluation of consensual response is necessary to rule out optic nerve dysfunction as a cause for lack of a direct light reflex. Because the optic nerve is the afferent pathway for the light reflex, shining a light into a blind eye produces neither a direct light response in that eye nor a consensual response in the opposite eye. A consensual response in the blind eye produced by shining a light into the opposite eye demonstrates an intact oculomotor nerve. Oculomotor compression associated with transtentorial herniation affects the direct light response and the consensual response in the affected pupil.1,2,11,12

Assessing Eye Movement

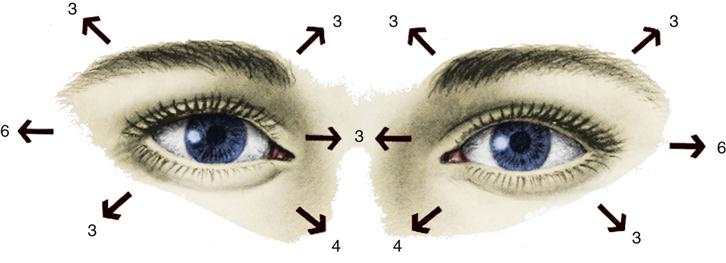

In the conscious patient, the function of the three cranial nerves of the eye and their MLF innervation can be assessed by asking the patient to follow a finger through the full range of eye motion. If the eyes move together into all six fields, extraocular movements are intact (Figure 17-3).1

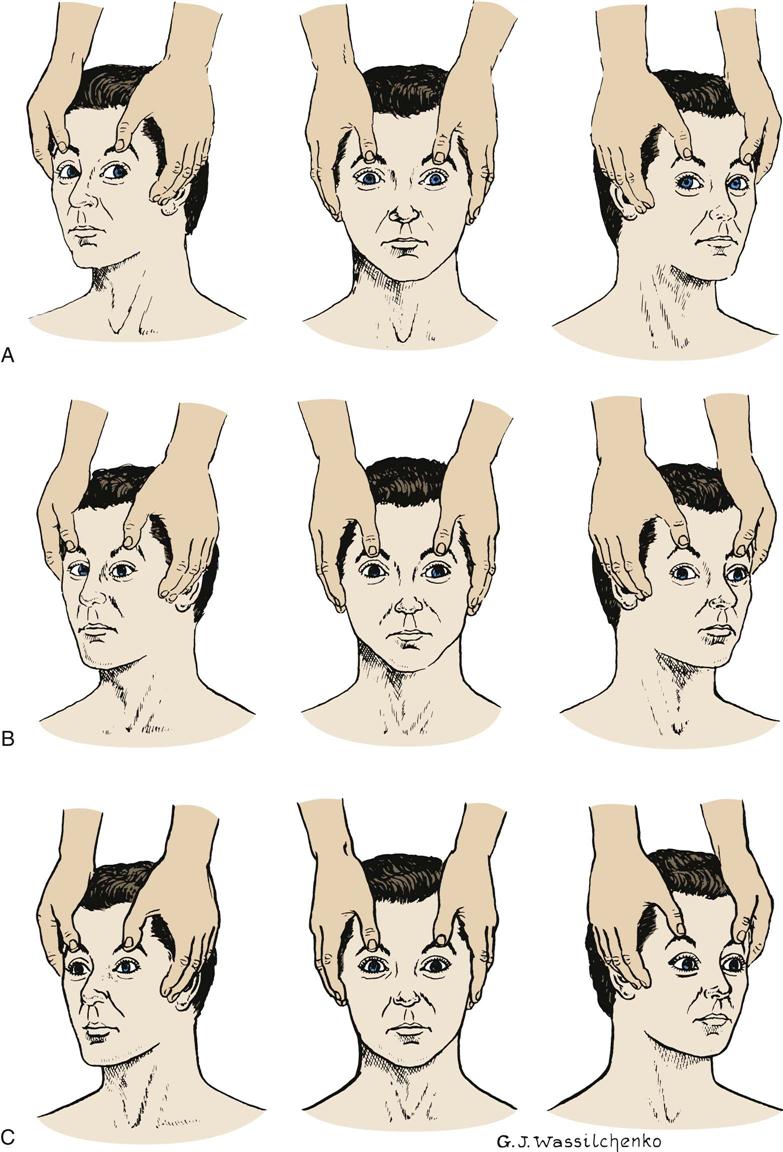

In the unconscious patient, assessment of ocular function and innervation of the MLF is performed by eliciting the doll’s eyes reflex. If the patient is unconscious as a result of trauma, the nurse must ascertain the absence of cervical injury before performing this examination. To assess the oculocephalic reflex, the nurse holds the patient’s eyelids open and briskly turns the head to one side while observing the eye movements and then briskly turns the head to the other side and observes. If the eyes deviate to the opposite direction in which the head is turned, the doll’s eyes reflex is present, and the oculocephalic reflex arc is intact (Figure 17-4, A). If the oculocephalic reflex arc is not intact, the reflex is absent. This lack of response, in which the eyes remain midline and move with the head, indicates significant brainstem injury (Figure 17-4, C). The reflex may also be absent in severe metabolic coma. An abnormal oculocephalic reflex is present when the eyes rove or move in opposite directions from each other (Figure 17-4, B). Abnormal oculocephalic reflex indicates some degree of brainstem injury.1–3

The oculovestibular reflex is performed by a physician, often as one of the final clinical assessments of brainstem function. After confirmation that the tympanic membrane is intact, the head is raised to a 30-degree angle, and 20 to 100 mL of ice water is injected into the external auditory canal. The normal eye movement response is a conjugate, slow, tonic nystagmus deviating toward the irrigated ear and lasting 30 to 120 seconds. This response indicates brainstem integrity. Rapid nystagmus returns the eyes back to the midline only in a conscious patient with cortical functioning (Figure 17-5).1 An abnormal response is disconjugate eye movement, which indicates a brainstem lesion, or no response, which indicates little or no brainstem function. The oculovestibular reflex may be temporarily absent in reversible metabolic encephalopathy.3 This test is an extremely noxious stimulation and may produce a decorticate or decerebrate posturing response in a comatose patient. In the conscious patient, this procedure may produce nausea, vomiting, or dizziness.1,12

Respiratory Function

Nursing priorities in assessment of respiratory function focus on (1) observing respiratory pattern and (2) evaluating airway status. The activity of respiration is a highly integrated function that receives input from the cerebrum, brainstem, and metabolic mechanisms. In clinical assessment, correlations exist among altered levels of consciousness, the level of brain or brainstem injury, and the patient’s respiratory pattern. Under the influence of the cerebral cortex and the diencephalon, three brainstem centers control respirations. The lowest center, the medullary respiratory center, sends impulses through the vagus nerve to innervate muscles of inspiration and expiration. The apneustic and pneumotaxic centers of the pons are responsible for the length of inspiration and expiration and the underlying respiratory rate.1–3

Observing Respiratory Pattern

Changes in respiratory patterns assist in identifying the level of brainstem dysfunction or injury. Evaluation of the respiratory pattern must include assessment of the effectiveness of gas exchange in maintaining adequate oxygen and carbon dioxide levels (Table 17-2). Hypoventilation is not uncommon in the patient with an altered level of consciousness. Alterations in oxygenation or carbon dioxide levels can result in further neurological dysfunction. ICP increases with hypoxemia or hypercapnia.1–3

TABLE 17-2

| PATTERN OF RESPIRATION | DESCRIPTION OF PATTERN | SIGNIFICANCE |

| Cheyne-Stokes | Rhythmic crescendo and decrescendo of rate and depth of respiration; includes brief periods of apnea | Usually seen with bilateral deep cerebral lesions or some cerebellar lesions |

| Central neurogenic hyperventilation | Very deep, very rapid respirations with no apneic periods | Usually seen with lesions of the midbrain and upper pons |

| Apneustic | Prolonged inspiratory and/or expiratory pause of 2-3 sec | Usually seen in lesions of the middle to lower pons |

| Cluster breathing | Clusters of irregular, gasping respirations separated by long periods of apnea | Usually seen in lesions of the lower pons or upper medulla |

| Ataxic respirations | Irregular, random pattern of deep and shallow respirations with irregular apneic periods | Usually seen in lesions of the medulla |

Evaluating Airway Status

Evaluation of the respiratory function in a patient with a neurological deficit must include assessment of airway maintenance and secretion control. Cough, gag, and swallow reflexes responsible for protection of the airway may be absent or diminished.13

Vital Signs

Nursing priorities in assessment of vital signs focus on (1) evaluating blood pressure and (2) monitoring heart rate and rhythm. As a result of the brain and brainstem influences on cardiac, respiratory, and body temperature functions, changes in vital signs can indicate deterioration in neurological status.

Evaluating Blood Pressure

A common manifestation of intracranial injury is systemic hypertension. Cerebral autoregulation, responsible for the control of cerebral blood flow (CBF), frequently is lost with any type of intracranial injury. After cerebral injury, the body often is in a hyperdynamic state (increased heart rate, blood pressure, and cardiac output) as part of a compensatory response. With the loss of autoregulation as blood pressure increases, CBF and cerebral blood volume increase, and ICP therefore increases. Control of systemic hypertension is necessary to stop this cycle, but caution must be exercised. The mean arterial pressure must be maintained at a level sufficient to produce adequate CBF in the presence of elevated ICP. Attention must also be paid to the pulse pressure because widening of this value may occur in the late stages of intracranial hypertension.13

Monitoring Heart Rate and Rhythm

The medulla and the vagus nerve provide parasympathetic control to the heart. When stimulated, this lower brainstem system produces bradycardia. Sympathetic stimulation increases the rate and contractility.14 Various intracranial pathologies and abrupt ICP changes can produce bradycardia, premature ventricular contractions (PVCs), QT changes, and myocardial damage.14,15

Cushing’s Triad

Cushing’s triad is a set of three clinical manifestations (bradycardia, systolic hypertension, and widening pulse pressure) related to pressure on the medullary area of the brainstem. These signs often occur in response to intracranial hypertension or a herniation syndrome. The appearance of Cushing’s triad is a late finding that may be absent in patients with neurological deterioration. Attention should be paid to alteration in each component of the triad and intervention initiated accordingly.3

Neurological Changes Associated With Intracranial Hypertension

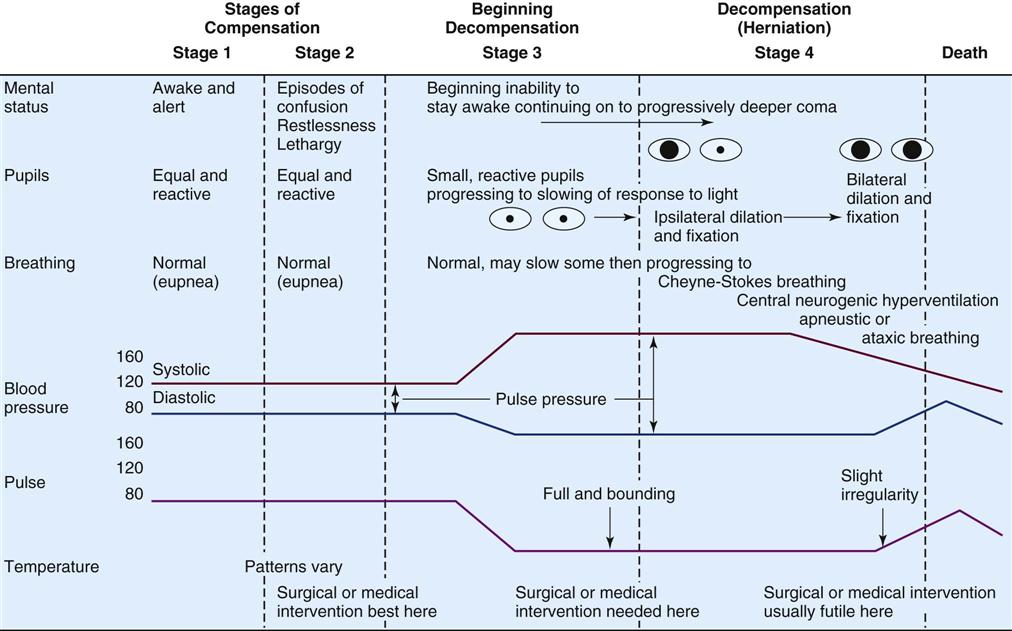

Assessment of the patient for signs of increasing ICP is an important responsibility of the critical care nurse. Increasing ICP can be identified by changes in level of consciousness, pupillary reaction, motor response, vital signs, and respiratory patterns (Figure 17-6).

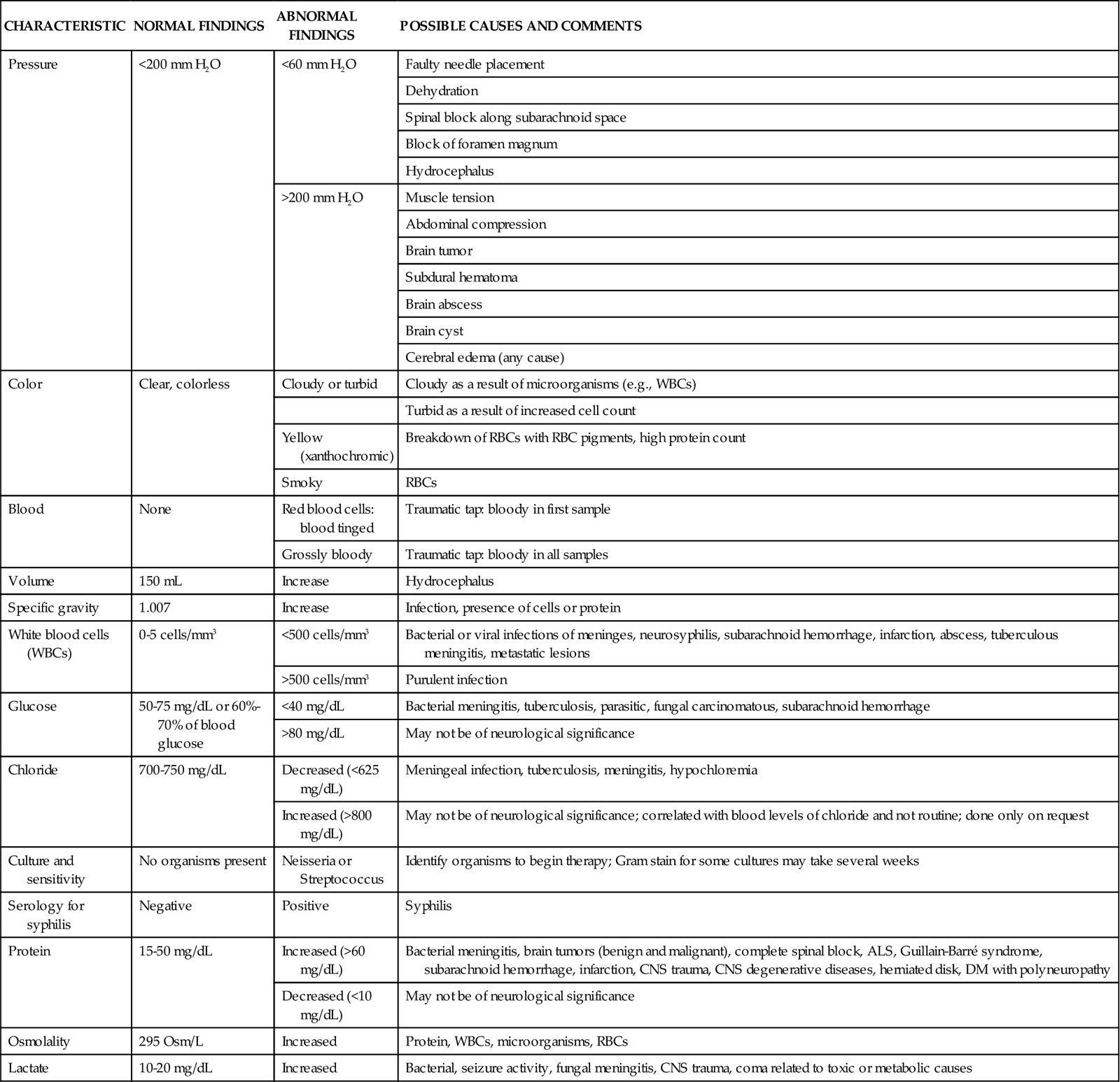

Laboratory Studies: Lumbar Puncture

The major laboratory study performed in the patient with neurological dysfunction is analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) obtained by a lumbar puncture or a ventriculostomy.1–3 The main purpose of a lumbar puncture is to obtain CSF for analysis. CSF opening pressure may also be obtained. CSF samples are evaluated for the presence of subarachnoid blood or infection, or they are sent for laboratory analysis (Table 17-3).

TABLE 17-3

ANALYSIS OF CEREBROSPINAL FLUID

| CHARACTERISTIC | NORMAL FINDINGS | ABNORMAL FINDINGS | POSSIBLE CAUSES AND COMMENTS |

| Pressure | <200 mm H2O | <60 mm H2O | Faulty needle placement |

| Dehydration | |||

| Spinal block along subarachnoid space | |||

| Block of foramen magnum | |||

| Hydrocephalus | |||

| >200 mm H2O | Muscle tension | ||

| Abdominal compression | |||

| Brain tumor | |||

| Subdural hematoma | |||

| Brain abscess | |||

| Brain cyst | |||

| Cerebral edema (any cause) | |||

| Color | Clear, colorless | Cloudy or turbid | Cloudy as a result of microorganisms (e.g., WBCs) |

| Turbid as a result of increased cell count | |||

| Yellow (xanthochromic) | Breakdown of RBCs with RBC pigments, high protein count | ||

| Smoky | RBCs | ||

| Blood | None | Red blood cells: blood tinged | Traumatic tap: bloody in first sample |

| Grossly bloody | Traumatic tap: bloody in all samples | ||

| Volume | 150 mL | Increase | Hydrocephalus |

| Specific gravity | 1.007 | Increase | Infection, presence of cells or protein |

| White blood cells (WBCs) | 0-5 cells/mm3 | <500 cells/mm3 | Bacterial or viral infections of meninges, neurosyphilis, subarachnoid hemorrhage, infarction, abscess, tuberculous meningitis, metastatic lesions |

| >500 cells/mm3 | Purulent infection | ||

| Glucose | 50-75 mg/dL or 60%-70% of blood glucose | <40 mg/dL | Bacterial meningitis, tuberculosis, parasitic, fungal carcinomatous, subarachnoid hemorrhage |

| >80 mg/dL | May not be of neurological significance | ||

| Chloride | 700-750 mg/dL | Decreased (<625 mg/dL) | Meningeal infection, tuberculosis, meningitis, hypochloremia |

| Increased (>800 mg/dL) | May not be of neurological significance; correlated with blood levels of chloride and not routine; done only on request | ||

| Culture and sensitivity | No organisms present | Neisseria or Streptococcus | Identify organisms to begin therapy; Gram stain for some cultures may take several weeks |

| Serology for syphilis | Negative | Positive | Syphilis |

| Protein | 15-50 mg/dL | Increased (>60 mg/dL) | Bacterial meningitis, brain tumors (benign and malignant), complete spinal block, ALS, Guillain-Barré syndrome, subarachnoid hemorrhage, infarction, CNS trauma, CNS degenerative diseases, herniated disk, DM with polyneuropathy |

| Decreased (<10 mg/dL) | May not be of neurological significance | ||

| Osmolality | 295 Osm/L | Increased | Protein, WBCs, microorganisms, RBCs |

| Lactate | 10-20 mg/dL | Increased | Bacterial, seizure activity, fungal meningitis, CNS trauma, coma related to toxic or metabolic causes |

From Barker E: Neuroscience nursing; a spectrum of care, ed 3, St Louis, 2008, Mosby.

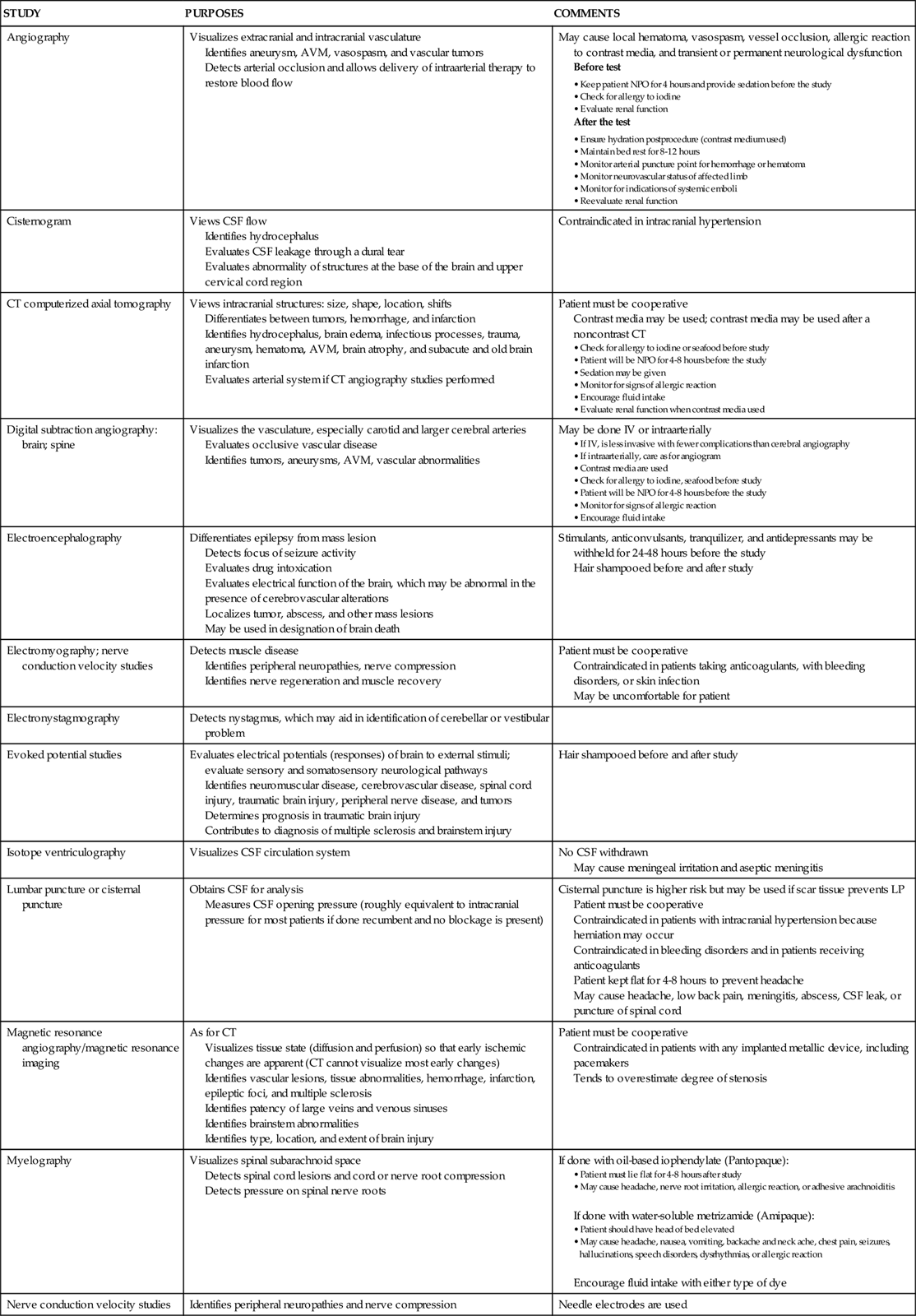

Diagnostic Procedures

Table 17-4 presents an overview of the various diagnostic procedures used to evaluate the patient with neurological dysfunction.

TABLE 17-4

NEUROLOGICAL DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

| STUDY | PURPOSES | COMMENTS |

| Angiography | Visualizes extracranial and intracranial vasculature Identifies aneurysm, AVM, vasospasm, and vascular tumors Detects arterial occlusion and allows delivery of intraarterial therapy to restore blood flow |

May cause local hematoma, vasospasm, vessel occlusion, allergic reaction to contrast media, and transient or permanent neurological dysfunction Before test After the test |

| Cisternogram | Views CSF flow Identifies hydrocephalus Evaluates CSF leakage through a dural tear Evaluates abnormality of structures at the base of the brain and upper cervical cord region |

Contraindicated in intracranial hypertension |

| CT computerized axial tomography | Views intracranial structures: size, shape, location, shifts Differentiates between tumors, hemorrhage, and infarction Identifies hydrocephalus, brain edema, infectious processes, trauma, aneurysm, hematoma, AVM, brain atrophy, and subacute and old brain infarction Evaluates arterial system if CT angiography studies performed |

Patient must be cooperative Contrast media may be used; contrast media may be used after a noncontrast CT |

| Digital subtraction angiography: brain; spine | Visualizes the vasculature, especially carotid and larger cerebral arteries Evaluates occlusive vascular disease Identifies tumors, aneurysms, AVM, vascular abnormalities |

May be done IV or intraarterially |

| Electroencephalography | Differentiates epilepsy from mass lesion Detects focus of seizure activity Evaluates drug intoxication Evaluates electrical function of the brain, which may be abnormal in the presence of cerebrovascular alterations Localizes tumor, abscess, and other mass lesions May be used in designation of brain death |

Stimulants, anticonvulsants, tranquilizer, and antidepressants may be withheld for 24-48 hours before the study Hair shampooed before and after study |

| Electromyography; nerve conduction velocity studies | Detects muscle disease Identifies peripheral neuropathies, nerve compression Identifies nerve regeneration and muscle recovery |

Patient must be cooperative Contraindicated in patients taking anticoagulants, with bleeding disorders, or skin infection May be uncomfortable for patient |

| Electronystagmography | Detects nystagmus, which may aid in identification of cerebellar or vestibular problem | |

| Evoked potential studies | Evaluates electrical potentials (responses) of brain to external stimuli; evaluate sensory and somatosensory neurological pathways Identifies neuromuscular disease, cerebrovascular disease, spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury, peripheral nerve disease, and tumors Determines prognosis in traumatic brain injury Contributes to diagnosis of multiple sclerosis and brainstem injury |

Hair shampooed before and after study |

| Isotope ventriculography | Visualizes CSF circulation system | No CSF withdrawn May cause meningeal irritation and aseptic meningitis |

| Lumbar puncture or cisternal puncture | Obtains CSF for analysis Measures CSF opening pressure (roughly equivalent to intracranial pressure for most patients if done recumbent and no blockage is present) |

Cisternal puncture is higher risk but may be used if scar tissue prevents LP Patient must be cooperative Contraindicated in patients with intracranial hypertension because herniation may occur Contraindicated in bleeding disorders and in patients receiving anticoagulants Patient kept flat for 4-8 hours to prevent headache May cause headache, low back pain, meningitis, abscess, CSF leak, or puncture of spinal cord |

| Magnetic resonance angiography/magnetic resonance imaging | As for CT Visualizes tissue state (diffusion and perfusion) so that early ischemic changes are apparent (CT cannot visualize most early changes) Identifies vascular lesions, tissue abnormalities, hemorrhage, infarction, epileptic foci, and multiple sclerosis Identifies patency of large veins and venous sinuses Identifies brainstem abnormalities Identifies type, location, and extent of brain injury |

Patient must be cooperative Contraindicated in patients with any implanted metallic device, including pacemakers Tends to overestimate degree of stenosis |

| Myelography | Visualizes spinal subarachnoid space Detects spinal cord lesions and cord or nerve root compression Detects pressure on spinal nerve roots |

If done with oil-based iophendylate (Pantopaque): • Patient must lie flat for 4-8 hours after study • May cause headache, nerve root irritation, allergic reaction, or adhesive arachnoiditis If done with water-soluble metrizamide (Amipaque): Encourage fluid intake with either type of dye |

| Nerve conduction velocity studies | Identifies peripheral neuropathies and nerve compression | Needle electrodes are used |

| Oculoplethysmography | Indirectly measures ocular artery pressure Reflects adequacy of cerebrovascular blood flow in the carotid artery retinal detachment |

Contraindicated in patients who have undergone eye surgery within the last 6 months, who have had lens implants or cataracts, or who have had retinal detachment May cause conjunctival hemorrhage, corneal abrasions, or transient photophobia |

| Pneumoencephalography | Visualizes ventricular system and subarachnoid space Identifies intracranial tumors Identifies brain atrophy |

Care as for LP Contraindicated in patients with intracranial hypertension May cause headache, nausea, vomiting, autonomic dysfunction, herniation, subdural hematoma, air embolus, or seizures Keep patient flat for 12-24 hours after the study |

| Positron emission tomography or single-photon emission computed tomography | Evaluates oxygen and glucose metabolism Measures cerebral blood flow, which may be altered by traumatic brain injury, seizure, ischemia, stroke, or neoplasm Also used to evaluate dementia, depression, schizophrenia, and Alzheimer’s disease |

Patient must be cooperative Contraindicated in pregnant and breastfeeding patients |

| Radioisotope brain scan | Identifies tumors, cerebrovascular disease, infarction, trauma, infectious processes, and seizures | Generally replaced by CT scan Reassure patient that amount of radioactive material is minimal Patient must be cooperative Contraindicated in pregnant and breastfeeding patients |

| Regional cerebral blood flow (xenon [133Xe] inhalation) | Evaluates blood flow to the cerebral cortex material Identifies cerebrovascular disease Detects regions of increased or decreased perfusion Determines presence of collateral blood flow Evaluates the effect of vasospasm on tissue perfusion |

Assure patient that amount of radioactive is minimal Contraindicated in pregnant and breastfeeding patients |

| Skull x-rays | Detects skull fracture, facial fracture, tumor, bone erosion, cranial anomalies, air-fluid level in sinuses, abnormal intracranial calcification, and radiopaque foreign bodies | Linear and basal fractures frequently missed by routine x-rays Contraindicated in pregnant patients |

| Somnography | Records electroencephalogram during sleep Evaluates sleep and sleep disorders |

|

| Spinal cord arteriography | Differentiates between spinal AVM, angioma, tumor, and ischemia | As for skull x-rays May cause thrombosis of spinal vessels and allergy to contrast agent |

| Spine x-rays | Detects vertebral dislocation or fracture, degenerative disease, tumor, bone erosion, or calcification Identifies structural spinal deficits and rules out associated cervical spine injuries |

Care must be taken to prevent fracture displacement and spinal cord injury C1-C2 view best obtained via open mouth; C6-C7 best obtained with arms pulled down |

| Suboccipital puncture | Obtains CSF for analysis Measures CSF pressure Rarely performed but may be useful when LP is contraindicated |

May cause trauma to the medulla |

| Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography | Measures blood flow velocity through the cerebral arteries Identifies vasospasm, emboli, vascular stenosis, and brain death |

Quality of findings and interpretation vary with user Transtemporal window required (lacking in 14% of general population) |

| Ventriculography | Obtains CSF for analysis Measures CSF pressure Is used especially when intracranial hypertension contraindicates LP |

May cause meningeal irritation, seizures, herniation, intracerebral or intraventricular hemorrhage |

From Dennison RD: Pass CCRN!, ed 3, St Louis, 2007, Mosby.

Nursing Management

The nursing management of a patient undergoing a diagnostic procedure involves a variety of interventions. Nursing priorities are directed toward (1) preparing the patient psychologically and physically for the procedure, (2) monitoring the patient’s responses to the procedure, and (3) assessing the patient after the procedure. Preparation includes teaching the patient about the procedure, answering questions, and transporting and positioning the patient for the procedure. During the procedure, the nurse observes the patient for signs of pain, anxiety, or hemorrhage and monitors vital signs. After the procedure, the nurse observes for complications of the procedure and medicates the patient for any postprocedure discomfort. Any evidence of increasing ICP should be immediately reported to the physician, and emergency measures to maintain circulation must be initiated.

Bedside Monitoring

Intracranial Pressure Monitoring

In the patient with suspected intracranial hypertension, a monitoring device may be placed within the cranium to quantify ICP. Under normal physiological conditions, mean ICP is maintained below 15 mm Hg. The device is used to monitor serial ICPs and assist with the management of intracranial hypertension. An increase in ICP can decrease blood flow to the brain, causing brain damage. It can also provide sterile access for draining excess CSF.16

Monitoring Sites

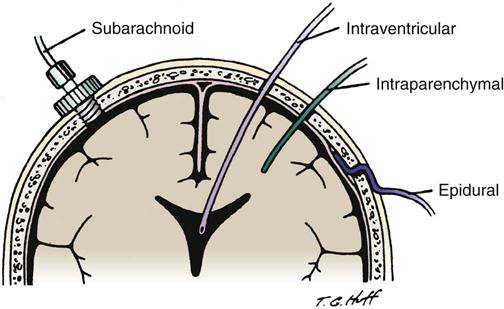

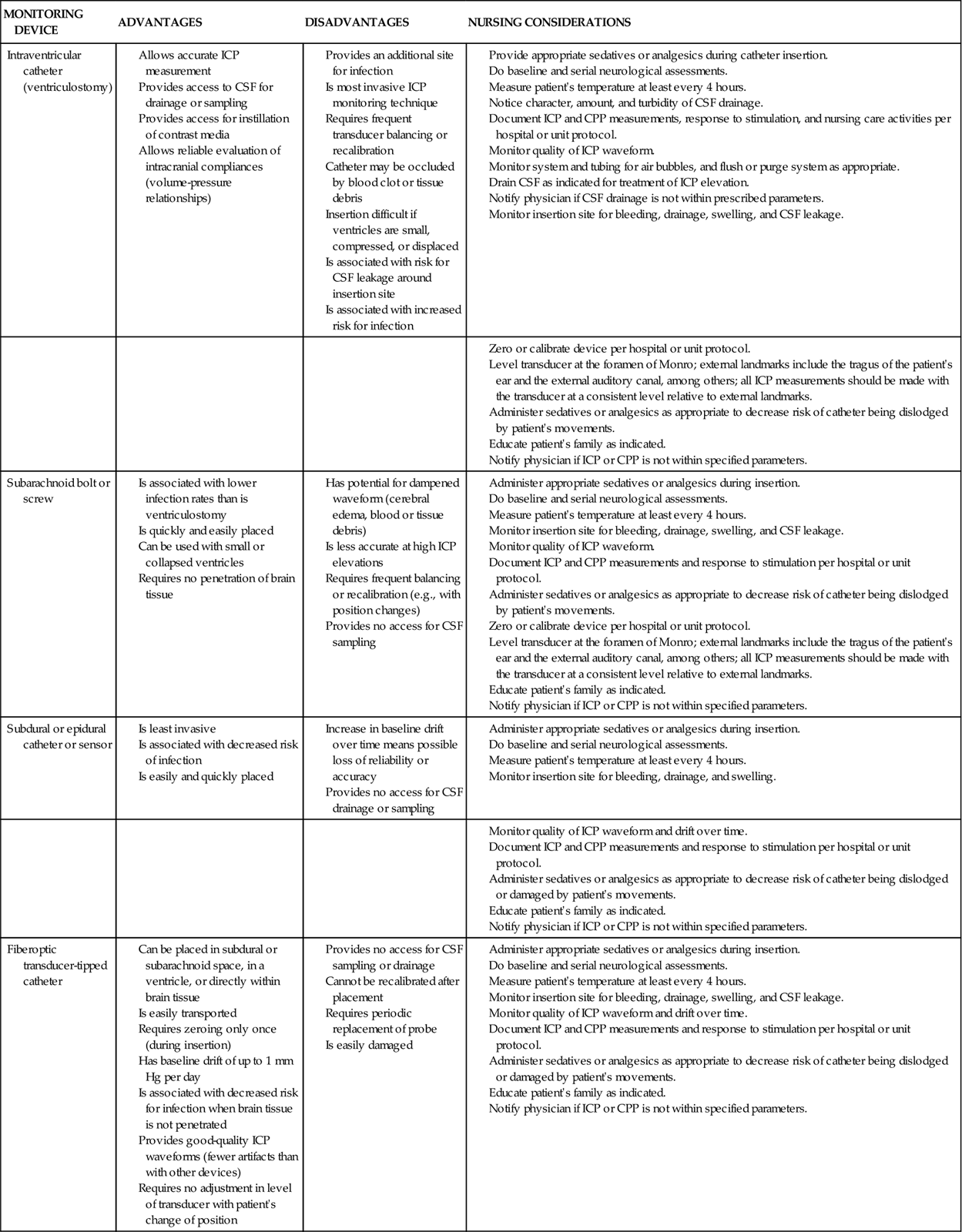

The four sites for monitoring ICP are the intraventricular space, the subarachnoid space, the epidural space, and the parenchyma (Figure 17-7). Each site has advantages and disadvantages for monitoring ICP (Table 17-5). The type of monitor chosen depends on the suspected pathological condition and physician’s preferences.16,17 Nursing considerations for each type of device are discussed in Table 17-5.

TABLE 17-5

ADVANTAGES, DISADVANTAGES, AND NURSING CONSIDERATIONS OF ICP MONITORING TECHNIQUES

CPP, cerebral perfusion pressure; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; ICP, intracranial pressure.

From Arbour R: Intracranial hypertension: monitoring and nursing assessment, Crit Care Nurse 24(5):19, 2004.

Intraventricular Space

ICP monitoring is accomplished by placing a small catheter into the ventricular system; this procedure is known as a ventriculostomy. The catheter is inserted through a burr hole with the patient under local anesthesia, and it usually is placed in the anterior horn of the lateral ventricle. If possible, the side chosen for placement of the ventriculostomy is the nondominant hemisphere.16,17

Subarachnoid Space

ICP monitoring is accomplished by placing a small hollow bolt or screw into the subarachnoid space. It is inserted through a burr hole, usually located in the front of the skull behind the hairline, with the patient under local anesthesia. Inserting this device is easier than inserting the ventriculostomy catheter.16,17

Epidural Space

ICP monitoring is accomplished by placing a small fiberoptic sensor into the epidural space. It is inserted through a burr hole while the patient is under local anesthesia. The physician strips the dura away from the inner table of the skull before inserting the epidural monitor.16,17

Intraparenchymal Site

ICP monitoring is accomplished by placing a small fiberoptic catheter into the parenchymal tissue. After placing a subarachnoid bolt (as previously described), a hole is punched in the dura, and the catheter is inserted approximately 1 cm into the brain’s white matter.16,17

Intracranial Pressure Waves

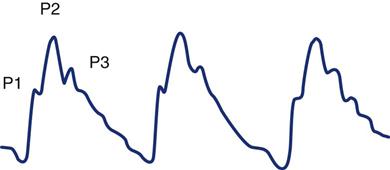

The ICP pulse waveform is observed on a continuous, real-time pressure display, and it corresponds to each heartbeat. The waveform arises primarily from pulsations of the major intracranial arteries but also receives retrograde venous pulsations.16,17

Normal Intracranial Pressure Waveform

The normal ICP wave has three or more defined peaks (Figure 17-8). The first peak (P1) is called the percussion wave. Originating from the pulsations of the choroid plexus, it has a sharp peak and is fairly consistent in its amplitude. The second peak (P2) is called the tidal wave. The tidal wave varies more in shape and amplitude, ending on the dicrotic notch. The P2 portion of the pulse waveform has been most directly linked to the state of decreased compliance. When the P2 component is equal to or higher than P1, decreased compliance occurs (Figure 17-9). Immediately after the dicrotic notch is the third wave (P3), which is called the dicrotic wave. After the dicrotic wave, the pressure usually tapers down to the diastolic position, unless retrograde venous pulsations add a few more peaks.16–19

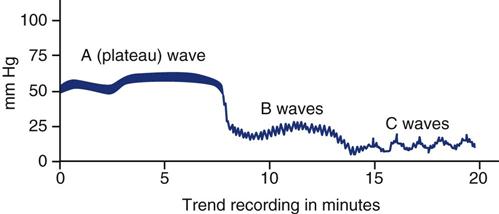

A, B, and C pressure waves are not true waveforms (Figure 17-10). Rather, they are the graphically displayed trend data of ICP over time. These waves reflect spontaneous alterations in ICP associated with respiration, systemic blood pressure, and deteriorating neurological status.

A Waves

Also called plateau waves because of their distinctive shape, A waves are the most clinically significant of the three types. They usually occur in an already elevated baseline ICP (>20 mm Hg) and are characterized by sharp increases in ICP of 30 to 69 mm Hg, which plateau for 2 to 20 minutes and then return to baseline. The cause of A waves is unknown, but they may result from vasodilation and increased CBF, decreased venous outflow (and therefore increased cerebral blood volume), fluctuations in PaCO2 (and therefore changes in cerebral blood volume), or decreased CSF absorption. B waves often precede A waves. Plateau waves are considered significant because of the reduced cerebral perfusion pressure associated with ICP, in the range of 50 to 100 mm Hg. Transient signs of intracranial hypertension, such as a decreased level of consciousness, bradycardia, pupillary changes, or respiratory changes, may accompany these waves. Some research suggests that prolonged increases in ICP associated with plateau waves may result in transient and permanent cell damage from ischemia.2,17

B Waves

B waves are sharp, rhythmic oscillations with a sawtooth appearance that occur every 30 seconds to 2 minutes and that can raise the ICP from 5 to 70 mm Hg. They are a normal physiological phenomenon that can occur in any patient, but they are amplified in states of low intracranial compliance. B waves appear to reflect fluctuations in cerebral blood volume. Decompensation of normal intracranial volume compensatory capacity is indicated by B waves with a high amplitude (>15 mm Hg pressure change from peak to trough of the wave).2,17

C Waves

C waves are small, rhythmic waves that occur every 4 to 8 minutes at normal levels of ICP. They are related to normal fluctuations in respiration and systemic arterial pressure. C waves are considered clinically insignificant.2,17

Cerebral Perfusion Pressure

Measuring CBF in the clinical setting is difficult, but at the bedside, an estimated pressure of cerebral perfusion can be derived. Cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) is the blood pressure gradient across the brain, and it is calculated as the difference between the incoming mean arterial pressure (MAP) and the opposing ICP on the arteries (see Appendix B).

The CPP in the average adult is approximately 80 to 100 mm Hg, with a range of 60 to 150 mm Hg. The CPP must be maintained near 80 mm Hg to provide adequate blood supply to the brain. If the CPP drops below this point, ischemia may develop. A sustained CPP of 30 mm Hg or less usually results in neuronal hypoxia and cell death. When the mean systemic arterial pressure equals the ICP, CBF may cease.1–3

Cerebral Oxygenation Monitoring

Cerebral Metabolism

The measurements of CBF and CPP do not address the brain’s metabolic need for oxygen. Active neurons require greater amounts of oxygen than those that are inactive. The determination that CBF matches the brain’s metabolic needs is expressed as cerebral metabolic rate (CMRO2), the normal value of which is 3.4 mL per 100 g of brain tissue per minute. Neuronal demand for oxygen is governed by the metabolic rate. For technical reasons, this value is not easily attained, although it can be calculated. It is the product of the measured CBF and calculated arteriojugular oxygen difference (AJDO2) (see Appendix B).20

CBF can be measured using a variety of complex techniques (e.g., PET, SPECT). Most recently, continuous bedside monitoring of regional cerebrocortical blood flow has become available.8 Arteriojugular oxygen difference is the amount of oxygen extracted by the brain, and it is reflected in the difference between the arterial oxygen content and the jugular venous oxygen content. The normal value is 5.0 to 7.5 vol%.20

Jugular Venous Oxygen Saturation

One method of measuring CBF allows continuous measurement of oxygenation within the jugular venous system through the use of the jugular bulb monitor. Jugular venous oxygen saturation (SjvO2) can be used to reflect cerebral oxygen supply-and-demand balance. Any disorder that increases CMRO2 or decreases oxygen delivery may decrease SjvO2, and conversely, any disorder that that decreases CMRO2 or increases oxygen delivery may increase SjvO2.20,21

To measure SjvO2 a fiberoptic catheter is placed retrograde through the internal jugular vein into the jugular bulb and attached to a bedside monitor. The normal value is 60% to 80%. Patients with values less than 50% and 55% are hypoxemic or oligemic (low CBF compared with metabolic rate). Oligemia occurs as a result of decreased blood flow due to hypotension, vasospasm, or intracranial hypertension or as a result of increased brain metabolic requirements due to fever or seizures.20,21 SjvO2 values below 45% are indicative of severe cerebral hypoxia.20 Patients with values above 75% to 80% are considered hyperemic (high CBF compared with metabolic need). SjvO2 also increases if the brain is so severely injured the neurons are unable to extract oxygen.20,21

SjvO2 monitoring has several limitations. SjvO2 is a global measure of cerebral oxygenation, and a normal SjvO2 value does not rule out localized areas of cerebral ischemia.20,21 Readings are affected by the movement of the patient’s head.21 Up to 50% of low SjvO2 readings are false, which may be caused by technical issues with the catheter, particularly catheter migration.22 For accurate reading, the tip of the catheter must be within 1 cm of the jugular bulb.21

Brain Tissue Oxygen Pressure

Over the past few years, a new device has become available to measure the partial pressure of oxygen within brain tissue (PbtO2). The device consists of a monitoring probe on the end of a catheter, which is inserted into the brain parenchyma and attached to a bedside monitor. The probe may be inserted into the damaged portion of the brain to measure regional oxygenation or inserted into the undamaged portion of the brain to measure global oxygenation. One risk associated with insertion of the catheter is bleeding with hematoma formation.23 Although there is no consensus on normal values because they vary from device to device, it has been concluded that the probability of death increases with prolonged periods of PbtO2 less than 15 mm Hg and any episode of PbtO2 less than 6 mm Hg.23

In the head-injured patient, the goal of treatment is to maintain the PbtO2 greater than 20 mm Hg. Factors that decrease PbtO2 include tissue hypoxia, hypocapnia, hypovolemia, decreased blood pressure, low hemoglobin levels, intracranial hypertension, and hyperthermia.24 Treatment is directed at the underlying cause.