Chapter 2 Neurologic Examination of the Older Child

Examination of a child older than 2 years should be as informal as possible while maintaining a basic flow pattern to permit complete evaluation. The older child has acquired a large repertory of skills since infancy (Box 2-1). For children between 2 and 5 years old, the Denver Developmental Screening Test II may be useful in evaluating various motor skills [Frankenburg et al., 1992] (see Chapter 1). Many neurologic functions of children between the ages of 2 and 4 years are examined in the same manner as those of children younger than 2 years. As is the case with younger children, some patients between 2 and 4 years old may be most comfortable sitting on a caregiver’s lap. The examining room should be equipped with small toys, dolls, and pictures with which to interest the child and provide for ease of interaction. Observation and play techniques are essential means of monitoring intellectual and motor function. Children may choose to move about the examining room and may be attracted to these various playthings. After 4 years of age, the components of the neurologic examination are more conventional and routine, and by adolescence, the examination is much the same as the adult examination.

Box 2-1 Emerging Patterns of Behavior from 1 to 5 years of Age

15 months

| Motor: | Walks alone; crawls up stairs |

| Adaptive: | Makes tower of two cubes; makes line with crayon; inserts pellet into bottle |

| Language: | Jargon; follows simple commands; may name familiar object (ball) |

| Social: | Indicates some desires or needs by pointing; hugs parents |

18 months

| Motor: | Runs stiffly; sits on small chair; walks up stairs with one hand held; explores drawers and waste baskets |

| Adaptive: | Piles three cubes; initiates scribbling; imitates vertical stroke; dumps pellet from bottle |

| Language: | Ten words (average); names pictures; identifies one or more parts of body |

| Social: | Feeds self; seeks help when in trouble; may complain when wet or soiled; kisses parents with pucker |

24 months

| Motor: | Runs well; walks up and down stairs one step at a time; opens doors; climbs on furniture |

| Adaptive: | Makes tower of six cubes; circular scribbling; imitates horizontal strokes; folds paper once imitatively |

| Language: | Puts three words together (subject, verb, object) |

| Social: | Handles spoon well; tells immediate experiences; helps to undress; listens to stories with pictures |

30 months

| Motor: | Jumps |

| Adaptive: | Makes tower of eight cubes; makes vertical and horizontal strokes but generally will not join them to make a cross; imitates circular stroke, forming closed figure |

| Language: | Refers to self by pronoun “I”; knows full name |

| Social: | Helps put things away; pretends in play |

36 months

| Motor: | Goes up stairs alternating feet; rides tricycle; stands momentarily on one foot |

| Adaptive: | Makes tower of nine cubes; imitates construction of “bridge” of three cubes; copies circle; imitates cross |

| Language: | Knows age and gender; counts three objects correctly; repeats three numbers or sentence of six syllables |

| Social: | Plays simple games (in “parallel” with other children); helps in dressing (unbuttons clothing and puts on shoes); washes hands |

48 months

| Motor: | Hops on one foot; throws ball overhand; uses scissors to cut out pictures; climbs well |

| Adaptive: | Copies bridge from model; imitates construction of “gate” of five cubes; copies cross and square; draws man with 2–4 parts besides head; names longer of two lines |

| Language: | Counts four pennies accurately; tells a story |

| Social: | Plays with several children with beginning of social interaction and role playing; goes to toilet alone |

60 months

| Motor: | Skips |

| Adaptive: | Draws triangle from copy; names heavier of two weights |

| Language: | Names four colors; repeats sentences of ten syllables; counts ten pennies correctly |

| Social: | Dresses and undresses; asks questions about meanings of words; domestic role playing |

(Adapted from Behrman RE, et al. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 14th edn. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1992.)

Physical Examination

Deep Tendon Reflexes

Deep tendon reflexes (i.e., muscle stretch reflexes) are readily elicited by conventional means with a reflex hammer while the child is sitting quietly. In the case of the biceps reflex, it may be helpful for the examiner to place his or her thumb on the tendon and strike the positioned thumb to elicit the reflex. If the child is crying or overtly resists, the examiner should postpone this portion of the examination. The child may be reassured if the examiner taps the brachioradialis reflex of the caregiver before performing the same act on the child. Deep tendon reflexes customarily examined include the biceps, triceps, brachioradialis, patellar, and Achilles reflexes. Each tendon reflex is mediated at a specific spinal segmental level or levels (Table 2-1) [Haymaker and Woodhall, 1962; Hollinshead, 1969].

| Reflex | Nerve | Segmental Level |

|---|---|---|

| Biceps | Musculocutaneous | C5, C6 |

| Brachioradialis | Radial | C5, C6 |

| Gastrocnemius and soleus (ankle jerk) | Tibial | L5, S1, S2 |

| Hamstring | Sciatic | L4, L5, S1, S2 |

| Jaw | Trigeminal | Pons |

| Quadriceps (knee jerk) | Femoral | L2–L4 |

| Triceps | Radial | C6, C8 |

The response to elicitation of deep tendon reflexes can be characterized as follows:

Other Reflexes

Developmental reflexes are discussed in Chapter 3. The persistence of developmental reflexes beyond the expected age of extinction is usually an indication of corticospinal tract impairment [Zafeiriou, 2004].

Cerebellar Function

Head tilt may be associated with tumors of the cerebellum. The tilt is usually ipsilateral to the involved cerebellar hemisphere, but exceptions are common. Herniation of the cerebellar tonsils through the foramen magnum resulting from increased intracranial pressure may cause head tilt; neoplasms that induce increased intracranial pressure, other than those of the cerebellum, may cause head tilt. Cerebellar function is also evaluated during testing of station and gait (see Chapter 5). Cerebellar dysfunction is usually associated with hypotonia.

Cranial Nerve Examination

Optic Nerve: Cranial Nerve II

Pupils should be observed in light that allows them to remain mildly mydriatic. The diameter, regularity of contour, and responsivity of the pupils to light should be examined. When the pupil is dilated and is minimally reactive or unresponsive to light, the patient may suffer from Adie’s pupil. The upper lid is usually at the margin of the pupil. In Horner’s syndrome, impairment of the sympathetic pathway results in a miotic pupil, mild ptosis, and defective sweating over the ipsilateral side of the face (Figure 2-1). Dragging a finger over the child’s forehead may aid in the recognition of anhidrosis. The fixed, dilated pupil usually is associated with other signs of oculomotor nerve dysfunction and may signify cerebral tonsillar herniation.

Oculomotor, Trochlear, and Abducens Nerves: Cranial Nerves III, IV, and VI

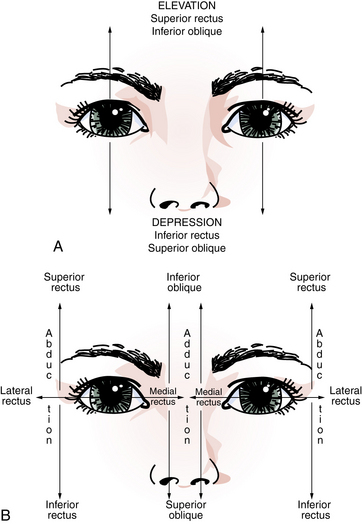

The oculomotor, trochlear, and abducens cranial nerves control extraocular motor movements; these nerves must operate synchronously or diplopia ensues. Cranial nerve III innervates the superior, inferior, and medial recti; the inferior oblique; and the eyelid elevator (levator palpebrae superioris). Cranial nerves IV and VI innervate the superior oblique muscle and the lateral rectus muscle, respectively. Unfortunately for purposes of understanding, the function of extraocular muscles depends somewhat on the direction of gaze. The lateral and medial recti are abductors and adductors of the globe, respectively. The superior rectus and inferior oblique are elevators, and the inferior rectus and superior oblique are depressors. The oblique muscles act in the vertical plane while an eye is adducted. The recti muscles serve this function when an eye is abducted (Figure 2-2). When directed forward (i.e., primary position), the oblique muscles effect torsion around the anteroposterior axis (rotation) of the globes [Cogan, 1966]. The eye position that results from paralysis of each eye muscle is listed in Table 2-2.

| Paretic Muscle | Cranial Nerve | Eye Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Inferior oblique | III | Down and out |

| Inferior rectus | III | Up and in |

| Lateral rectus | VI | Medial |

| Medial rectus | III | Lateral |

| Superior oblique | IV | Upward and outward (head tilted) |

| Superior rectus | III | Down and in |

Extraocular muscle dysfunction is associated with many conditions that affect the brainstem, cranial nerves, neuromuscular junction, or muscles. Among the diseases are ophthalmoplegic migraine, cavernous sinus thrombosis, brainstem glioma, myasthenia gravis, and congenital myopathy. Cranial nerve VI function may be impaired by increased intracranial pressure, irrespective of cause. Squint, usually esotropia, often accompanies decreased visual acuity in infants and young children [Smith, 1967].

Ptosis and extraocular muscle paralysis accompany dysfunction of cranial nerve III. Ptosis resulting from oculomotor nerve compromise is usually more pronounced than is the malposition of the lid associated with Horner’s syndrome. This symptom is a great diagnostic aid because the lid does not significantly elevate when the patient is asked to look up. Complete oculomotor nerve paralysis, although uncommon, causes the eye to position downward and outward. Poor adduction and elevation are also evident (see Figure 2-1).

Brainstem lesions, especially those in the midbrain or pons, may disrupt the medial longitudinal fasciculus. The resultant impairment of conjugate eye movement is referred to as an internuclear ophthalmoplegia. These lesions engender weakness of medial rectus muscle contraction of the adducting eye, which is accompanied by a monocular nystagmus in the abducting eye. Occasionally, paresis of lateral rectus muscle movement in the abducting eye may occur. Medial longitudinal fasciculus involvement may be unilateral or bilateral, and may be associated with a number of brainstem conditions, including hemoglobinopathies, demyelinating disease, or brainstem vascular disease [Cogan, 1966].

Nystagmus, especially vertical nystagmus, is most commonly induced by medications (e.g., barbiturates, phenytoin, carbamazepine, benzodiazepines). Such nystagmus often has a jerk component and is usually most prominent in the direction of gaze. Vertical nystagmus that is not associated with medications indicates brainstem dysfunction. A few beats of horizontal nystagmus with extreme lateral gaze are usually normal. Persistent horizontal nystagmus indicates dysfunction of the cerebellum or brainstem vestibular system components; the nystagmus is coarser (i.e., the amplitude of movements are greater) when the direction of gaze is toward the side of the lesion. A rare condition, seesaw nystagmus, is characterized by disconjugate (alternating) movement of the eyes, which move upward and downward in a seesaw motion. This type of nystagmus accompanies lesions in the region of the optic chiasm (see Chapter 6).

Trigeminal Nerve: Cranial Nerve V

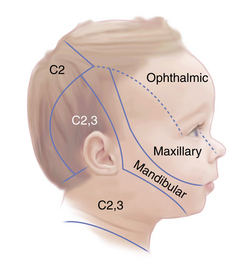

Cranial nerve V is also responsible for sensation involving the face and the anterior half of the scalp (Figure 2-3). Brainstem compromise can effect clearly delineated laminar sensory deficits; however, mapping of such deficits is difficult in children. The corneal reflex, provided its sensory input by the trigeminal nerve, may be diminished or absent after trauma, in cerebellopontine angle tumors, brainstem tumors, cavernous sinus thrombosis, Gradenigo’s syndrome, or childhood collagen–vascular diseases.

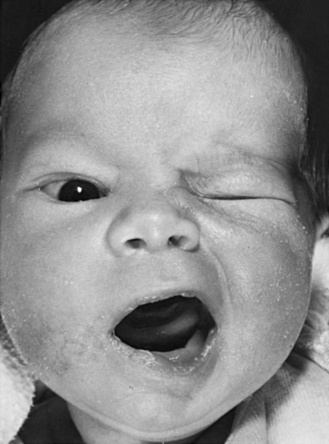

Facial Nerve: Cranial Nerve VII

Taste sensation over the anterior two-thirds of the tongue, secretory fibers (parasympathetic) innervating the lacrimal and salivary glands, and innervation of all facial muscles are accomplished by cranial nerve VII. Complete motor dysfunction on one side of the face ensues when the cranial nerve VII pathway is disrupted in the nucleus, pons, or peripheral nerve. The patient is unable to move the forehead upward, close the eye forcefully, or elevate the corner of the mouth on the side of the affected nerve (Figure 2-4 and Figure 2-5).

Fig. 2-4 Right facial paralysis of the peripheral type.

(Courtesy of the Division of Pediatric Neurology, University of Minnesota Medical School.)

Central (supranuclear) facial nerve impairment produces only paresis of the muscles involving the lower face, with resultant drooping of the angle of the mouth, disappearance or diminution of the nasal labial fold, and widened palpebral fissure. The muscles of the forehead, which are innervated bilaterally, are unaffected. Cardiofacial syndrome is a congenital weakness that causes failure of depression of the angle of the mouth and is unrelated to facial nerve palsy (see Chapter 4).

Auditory Nerve: Cranial Nerve VIII

Function and evaluation of cranial nerve VIII are discussed in detail in Chapters 7 and 8. Although cranial nerve VIII is known as the auditory nerve, it has auditory and vestibular functions. Gross auditory impairment may be suspected during the history-taking session while the child is in the room. The child may not respond directly to questions or to directions from the caregivers. More specific testing with whispered language, the ticking of a watch, a party noisemaker, or a tuning fork may be used to gain more information.

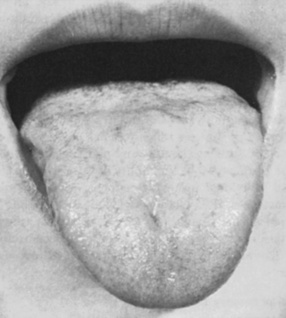

Hypoglossal Nerve: Cranial Nerve XII

The tongue muscle is the primary responsibility of cranial nerve XII. Atrophy and fasciculation of the tongue occur when the ipsilateral hypoglossal nucleus or hypoglossal nerve is involved. The protruded tongue deviates toward the involved side because contraction of the normally innervated tongue muscle causes protrusion and is unopposed. The child cannot push the tongue against the cheek of the unaffected side. Speech may be muffled or dysarthric. Bilateral involvement of hypoglossal nuclei or cranial nerve XII may be severely incapacitating. The tongue muscle may be markedly atrophied, and fasciculations of the tongue may be very prominent (Figure 2-6). The patient may be unable to protrude the tongue beyond the lips, and there is marked dysarthria with unintelligibility of speech. Although chewing and swallowing are somewhat affected by unilateral tongue weakness, bilateral involvement results in gross difficulty.

Sensory System

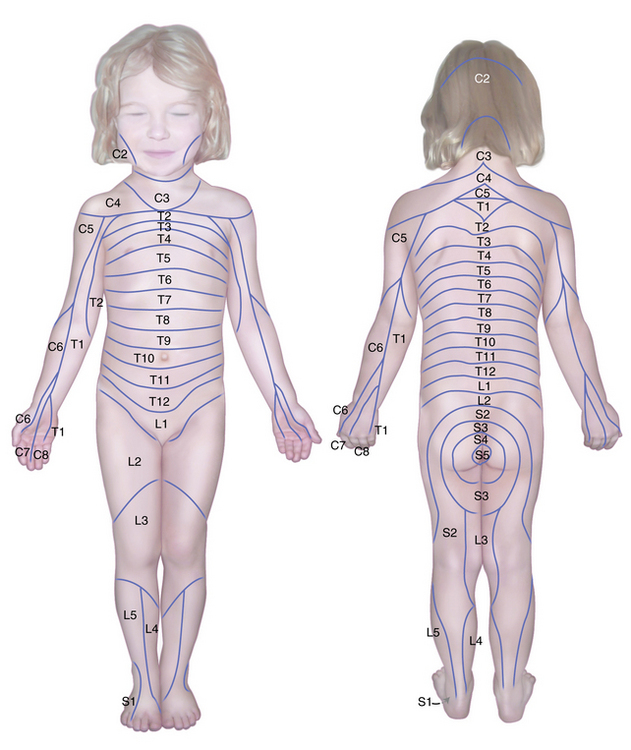

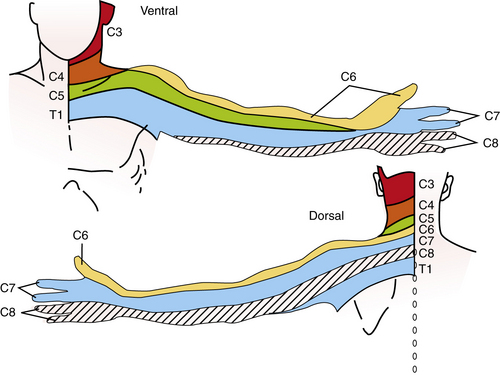

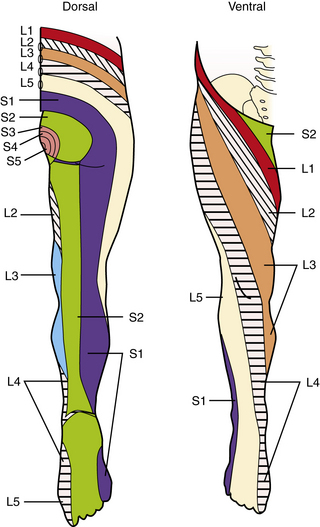

Testing for segmental sensory level during childhood is sometimes an essential portion of the examination. Because the patient must be attentive and cooperative, the examination often has to be repeated for corroboration. Segmental sensory innervations of the arm and leg are illustrated in Figure 2-7, Figure 2-8, and Figure 2-9 [Keegan and Garrett, 1948]. The nipples are at approximately the T5 level and the umbilicus at the T10 level.

Fig. 2-7 Segmental sensory innervation of the arm.

(Courtesy of the Division of Pediatric Neurology, University of Minnesota Medical School; adapted from Keegan JJ, Garrett FD. The segmental distribution of the cutaneous nerves in the limbs of man. Anat Rec 1948;102:409. Reprinted with permission of Wiley–Liss, Inc., a subsidiary of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.)

Fig. 2-8 Segmental sensory innervation of the leg.

(Courtesy of the Division of Pediatric Neurology, University of Minnesota Medical School, adapted from Keegan JJ, Garrett FD. The segmental distribution of the cutaneous nerves in the limbs of man. Anat Rec 1948;102:409. Reprinted with permission of Wiley–Liss, Inc., a subsidiary of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.)

The ability to distinguish between closely approximated stimulation at two points is two-point discrimination. The minimal distance between two simultaneous points of stimulation is determined. Normal findings have been reported for children 2–12 years old [Cope and Antony, 1992]. Testing of this modality is frequently performed over the fingertips. Differences in perception over homologous areas on both sides are sought. Absence or impairment of two-point discrimination results from parietal lobe dysfunction.

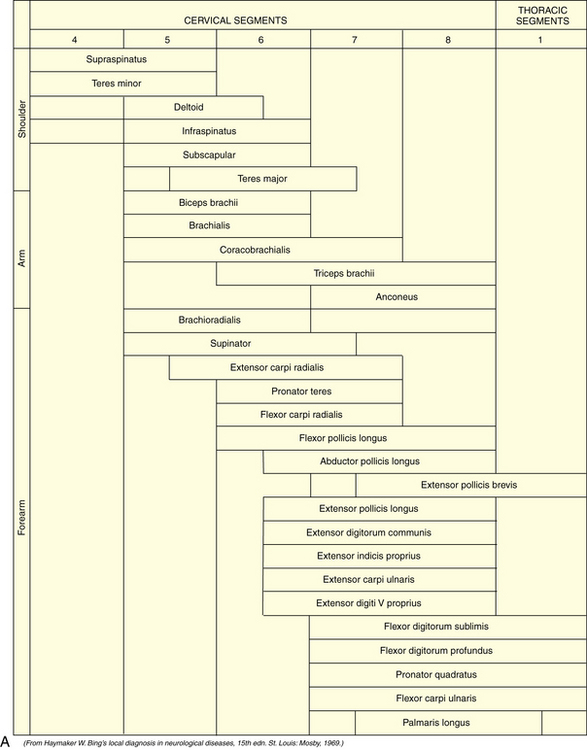

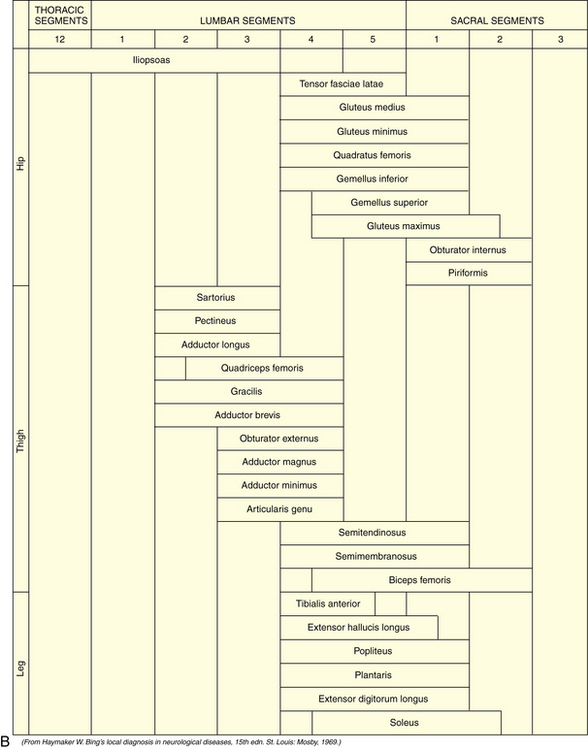

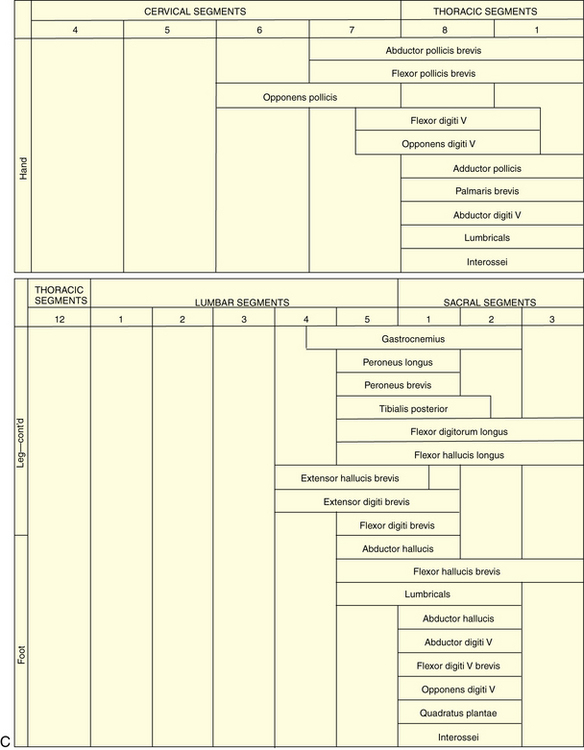

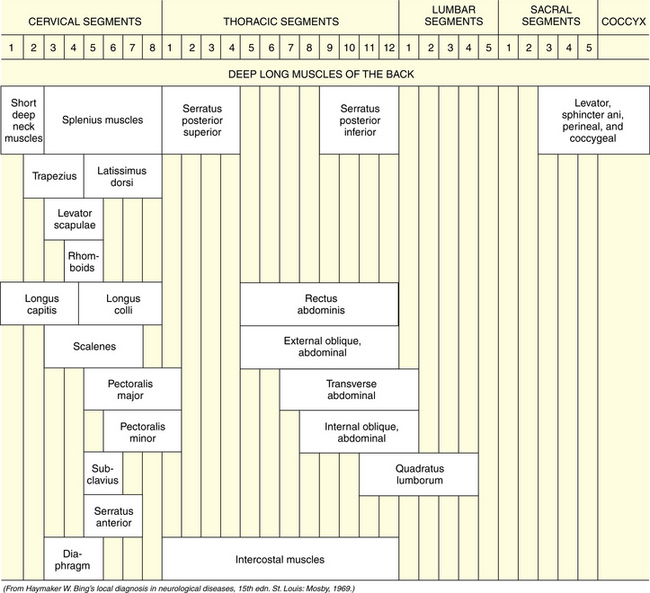

Skeletal Muscles

Tone, bulk, and strength of the skeletal muscles should be determined during this portion of the examination. The segmental innervation patterns of the trunk muscles and the extremities and the motor functions of the spinal nerves are described in Table 2-3, Table 2-4, and Table 2-5.

| Nerves | Muscles* | Function |

|---|---|---|

| CERVICAL PLEXUS (C1–C4) | ||

| Cervical | Deep cervical | Flexion, extension, and rotation of neck |

| Phrenic | Scalene | Elevation of ribs (inspiration) |

| Diaphragm | Inspiration | |

| BRACHIAL PLEXUS (C5–T1) | ||

| Anterior | Pectorales major and minor | Adduction and depression of arm downward and medially |

| Long thoracic | Serratus anterior | Fixation of scapula on raising arm |

| Dorsal scapular | Levator scapulae | Elevation of scapula |

| Rhomboid | Drawing scapula upward and inward | |

| Suprascapular | Supraspinatus | Outward rotation of arm |

| Infraspinatus | Elevation and outward rotation of arm | |

| Subscapular | Latissimus dorsi | |

| Teres major | Inward rotation and abduction of arm toward the back | |

| Subscapularis | Inward rotation of arm | |

| Axillary | Deltoid | Raising of arm to horizontal |

| Teres minor | Outward rotation of arm | |

| Musculocutaneous | Biceps brachii | Flexion and supination of forearm |

| Coracobrachialis | Elevation and adduction of arm | |

| Brachialis | Flexion of forearm | |

| Median | Flexor carpi radialis | Flexion and radial deviation of hand |

| Palmaris longus | Flexion of hand | |

| Flexor digitorum sublimis | Flexion of middle phalanges of second through fifth fingers | |

| Flexor pollicis longus | Flexion of distal phalanx of thumb | |

| Flexor digitorum profundus (radial half) | Flexion of distal phalanges of second and third fingers | |

| Pronator quadratus | Pronation | |

| Pronator teres | Pronation | |

| Abductor pollicis brevis | Abduction of metacarpus I at right angles to palm | |

| Flexor pollicis brevis | Flexion of proximal phalanx of thumb | |

| Lumbricals I, II, III | Flexion of proximal phalanges and extension of other phalanges of first, second, and third fingers | |

| Opponens pollicis brevis | Opposition of metacarpus I | |

| Ulnar | Flexor carpi ulnaris | Flexion and ulnar deviation of hand |

| Flexor digitorum profundus (ulnar half) | Flexion of distal phalanges of fourth and fifth fingers | |

| Adductor pollicis | Adduction of metacarpus I | |

| Hypothenar | Abduction, opposition, and flexion of little finger | |

| Lumbricals III, IV | Flexion of first phalanx and extension of other phalanges of fourth and fifth fingers | |

| Interossei | Same action as preceding. Also spreading apart and bringing together of fingers | |

| Radial | Triceps brachii | Extension of forearm |

| Brachioradialis | Flexion of forearm | |

| Extensor carpi radialis | Extension and radial flexion of hand | |

| Extensor digitorum communis | Extension of proximal phalanges of second through fifth fingers | |

| Extensor digiti quinti proprius | Extension of proximal phalanx of little finger | |

| Extensor carpi ulnaris | Extension and ulnar deviation of hand | |

| Supinator | Supination of forearm | |

| Abductor pollicis longus | Abduction of metacarpus I | |

| Extensor pollicis brevis | Extension of proximal phalanx of thumb | |

| Extensor pollicis longus | Abduction of metacarpus I and extension of distal phalanges of thumb | |

| Extensor indicis proprius | Extension of proximal phalanx of index finger | |

| THORACIC NERVES | ||

| Thoracic | Thoracic and abdominal | Elevation of ribs, expiration, abdominal compression, etc. |

| LUMBAR PLEXUS (T12–L4) | ||

| Femoral | Iliopsoas | Flexion of leg at hip |

| Sartorius | Inward rotation of leg together with flexion of upper and lower leg | |

| Quadriceps femoris | Extension of lower leg | |

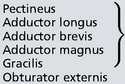

| Obturator |  |

|

| Adduction of leg | ||

| Adduction and outward rotation of leg | ||

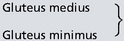

| SACRAL PLEXUS (L5–S5) | ||

| Superior gluteal |  |

Abduction and inward rotation of leg; also, under certain circumstances, outward rotation |

| Tensor fasciae latae | Flexion of leg at hip | |

| Piriformis | Outward rotation of leg | |

| Gluteus maximus | Extension of leg at hip | |

| Inferior gluteal | ||

| Sciatic |  |

|

| Outward rotation of leg | ||

| Biceps femoris | Flexion of leg at hip | |

| Semitendinosus | ||

| Semimembranosus | ||

| Peroneal | Tibialis anterior | Dorsiflexion and supination of foot |

| Deep | Extensor digitorum longus | Extension of toes |

| Extensor hallucis brevis | Extension of great toe | |

| Superficial | Peroneus | Pronation of foot |

| Tibialis |  |

Plantar flexion of foot |

| Tibialis posterior | Adduction of foot | |

| Flexor digitorum longus | Flexion of distal phalanges II–V | |

| Flexor hallucis longus | Flexion of distal phalanx I | |

| Flexor digitorum brevis | Flexion of middle phalanges II–V | |

| Flexor hallucis brevis | Flexion of middle phalanx I | |

| Plantar | Spreading, bringing together and flexion of proximal phalanges of toes | |

| Pudendal | Perineal anal sphincters | Closure of sphincters of pelvic organs; participation in sexual act; contraction of pelvic floor |

* Various muscles may receive still other nerve supplies than those mentioned. The following are the principal accessory nerve supplies: the brachial muscle receives fibers from the radial nerve; the flexor digitorum sublimis, from the ulnar; the adductor pollicis, from the median; the pectineus, from the femoral; the adductor magnus, from the tibial.

(From Haymaker W. Bing’s Local Diagnosis in Neurological Diseases, 15th edn. St. Louis: Mosby, 1969.)

Table 2-4 Segmental Innervation of Muscles of Extremities

Table 2-5 Segmental Innervation of Trunk Muscles

The strength of limb muscles is assessed, when possible, by testing the child’s ability to counteract resistance imposed by the examiner on proximal and distal muscle groups or individual muscles. Norms cited for gross motor outcomes in young children with brain injury are useful in assessing children with apparent motor difficulties [Golomb et al., 2004].

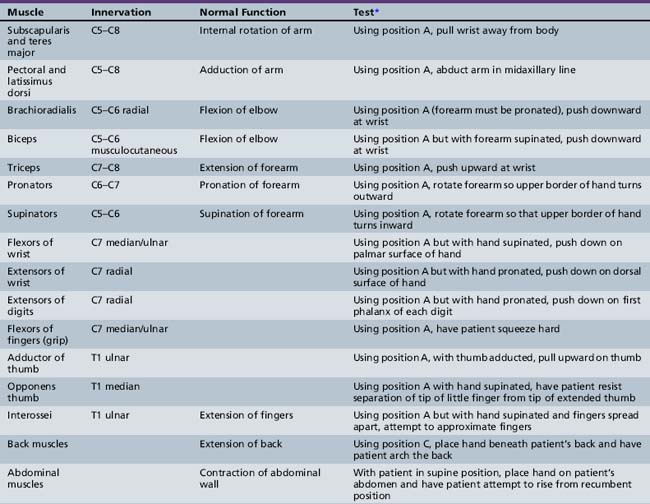

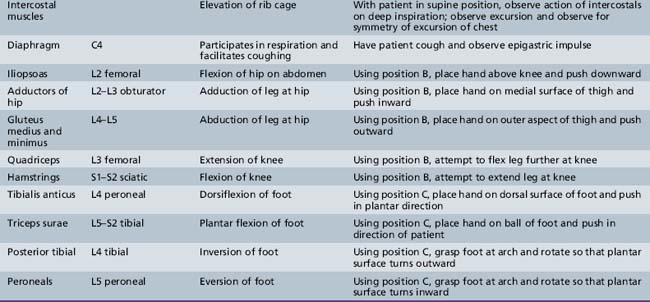

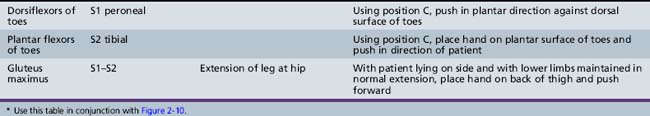

Muscle Testing

The skeletal muscles selected in the subsequent text are responsible for primary movements (Table 2-6). The material presented is adapted from Baker [1958]. Frequently, more than one muscle participates in the movement. For this reason, while testing the selected muscles, the examiner should observe and palpate surrounding muscles to detect any substitution of action of other muscles.

The following scoring system is useful for recording muscle power*:

While testing for muscle function, it is most convenient for the patient to maintain a fixed position against force. The examiner can assess the strength of various muscles by instituting the action of the antagonist. This strategy obviates the necessity for providing new directions for each muscle tested and simplifies the procedure for patient and examiner. The fixed positions depicted in Figure 2-10 are used routinely here and are referred to by the following letters:

Position A: The arm is adducted, the forearm flexed at the elbow, and the wrist placed across the xiphoid process.

Position A: The arm is adducted, the forearm flexed at the elbow, and the wrist placed across the xiphoid process. Position B: The child lies on the back with the lower extremity flexed at 90 degrees at the hip and knee. The examiner should support the lower limb at the ankle.

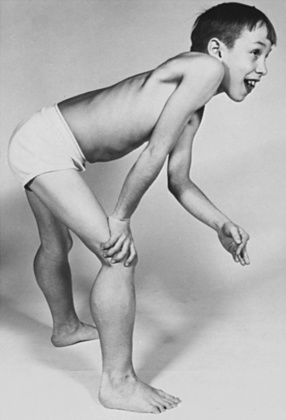

Position B: The child lies on the back with the lower extremity flexed at 90 degrees at the hip and knee. The examiner should support the lower limb at the ankle.Arm and shoulder strength can also be assessed by using functional operations. The child is asked to lean against a wall with the legs placed a foot or two from the wall edge and the arms outstretched with the palms against the wall. Strength of the shoulder girdle and arm extension can be evaluated. Winging of the scapulas also is evident. Alternatively, the child can be placed on the floor and asked to “wheelbarrow.” The child should be placed on the floor and asked to rise without assistance. The normal child will spring erect. The child with weakness of the hip extensors will engage in Gowers’ maneuver, and climb up the legs and push off into the erect position (Figure 2-11).

Fig. 2-11 Gowers’ maneuver indicates weakness of truncal and proximal lower extremity muscles.

(Courtesy of the Division of Pediatric Neurology, University of Minnesota Medical School.)

During examination of gait, the examiner must be aware of the presence of normal associated movements of the arms, circumduction of the legs, footdrop, unusual positions of the feet, and waddling (see Chapter 5). The presence of a limp may also be evident.

Gait evaluation

The evaluation of gait is discussed in detail in Chapter 5, but a brief outline is presented here. The child should be asked to walk back and forth normally, preferably in a corridor, and up and down steps. The examiner should observe whether the gait is wide- or narrow-based, whether there are symmetric reciprocal movements of the arms, and whether the legs and feet move in a symmetric and normal fashion. The child should also be asked to run because running exaggerates neurologic impairment. Flexion or extension of an arm with subsequent athetosis not present during walking may be apparent during running.

Among the abnormal gaits are those that can be characterized as cerebellar, spastic, waddling, and steppage. These gait types are discussed further in Chapter 5.

References

![]() The complete list of references for this chapter is available online at www.expertconsult.com.

The complete list of references for this chapter is available online at www.expertconsult.com.

Baker A.B. An outline of clinical neurology. Dubuque, Iowa: William C Brown, 1958.

Cogan D.G. Neurology of the ocular muscles. Springfield, Ill: Charles C Thomas, 1966.

Cope E.B., Antony J.H. Normal values for two-point discrimination. Pediatr Neurol. 1992;8:251.

Frankenburg W.K., Dodds J.B., Archer P., et al. The Denver II: A major revision and restandardization of the Denver Developmental screening test. Pediatrics. 1992;89:91.

Golomb M.R., Garg B.P., Williams L.S. Measuring gross motor recovery in young children with early brain injury. Pediatr Neurol. 2004;31:311.

Haymaker W. Bing’s local diagnosis in neurological diseases, ed 15. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1969.

Haymaker W., Woodhall B. Peripheral nerve injuries. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1962.

Hollinshead W.H. Functional anatomy of the limbs and back, ed 3. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1969.

Keegan J.J., Garrett F.D. The segmental distribution of the cutaneous nerves in the limbs of man. Anat Rec. 1948;102:409.

Smith J.L., editor. Neuro-ophthalmology: Symposium of the University of Miami and the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, vol 3. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1967.

Zafeiriou D.I. Primitive reflexes and postural reactions in the neurodevelopmental examination. Pediatr Neurol. 2004;31:1.

Brett E.M.. Normal development and neurological examination beyond the newborn period. Paediatric Neurology. ed 3. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1997.

Dekaban A. Examination. In: Dekaban A., editor. Neurology of early childhood. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1970.

Dodge P.R. Neurologic history and examination. In: Farmer T.W., editor. Pediatric neurology. New York: Paul B Hoeber, 1964.

Egan D.F. Developmental examination of infants and preschool children. Clinics in developmental medicine. Oxford: MacKeith Press, 1990. no. 112

Fenichel G.M. Clinical pediatric neurology: a signs and symptoms approach, ed 5. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2005.

Haerer A.F. Dejong’s the neurologic examination. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1992.

Iannetti P., Spalice A., Iannetti L., et al. Residual and persistent Adie’s pupil after pediatric ophthalmoplegic migraine. Pediatr Neurol. 2009;41:204.

Illingworth R.S. The development of the infant and young child, ed 9. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1987.

Kestenbaum A. Clinical methods of neuro-ophthalmologic examination. New York: Grune & Stratton, 1961.

Menkes J.H., Sarnat H.B., Maria B. Textbook of Child Neurology, ed 7. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

Nellhaus G. Composite international and interracial graphs. Pediatrics. 1968;41:106.

Paine R.S. Neurologic examination of infants and children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1960;7:41.

Paine R.S. Neurologic conditions in the neonatal period: diagnosis and management. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1961;8:577.

Paine R.S. The evolution of infantile postural reflexes in the presence of chronic brain syndromes. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1964;6:345.

Paine R.S., Brazelton T.B., Donovan D.E., et al. Evolution of postural reflexes in normal infants and in the presence of chronic brain syndromes. Neurology. 1964;14:1036.

Paine R.S., Oppe T.E. Neurological examination of children. London: William Heinemann, 1966.

Peiper A. Cerebral function in infancy and childhood. New York: Consultants Bureau Enterprises, 1963.

Popich G.A., Smith D.W. Fontanels: Range of normal size. J Pediatr. 1972;80:749.

Sauer C., Levinsohn M.W. Horner’s syndrome in childhood. Neurology. 1976;26:216.

Volpe J.J. The neurological examination: Normal and abnormal features. In Volpe J.J., editor: Neurology of the newborn, ed 5, Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2008.