Chapter 3 Neurologic Examination after the Newborn Period until 2 Years of Age

The first two years of life are a time of rapid changes in the acquisition of development skills and responses based on maturation of physiologic processes and anatomic structures of the developing central and peripheral nervous systems. Visual, sensory, and motor pathways are the most rapidly evolving in the first year of life, but the bases of social communication and language are also becoming more orgainized and sophisticated with each passing month. Neurologic assessment depends on comparing the results of the infant’s examination with established norms (Box 3-1) [Gesell and Amatruda, 1956; Illingsworth, 1987; Zafeiriou, 2004]. In some ways the examination is easier than that of a neonate because older infants and toddlers maintain alertness for much longer periods and can interact meaningfully with the examiner, but sudden or painful manipulation and stranger anxiety can lead to a screaming child and upset parents. As it is critical that the infant remain calm and cooperative for the longest possible time during the examination, the least intrusive portions of the examination should be done first. A review of Chapter 2 can assist in understanding the material in this chapter.

Box 3-1 Child Development from 2 Months through 2 Years

(Data from Frankenburg et al., 1981; Illingsworth RS, 1987; Knobloch H et al., 1980.)

Approach to the Evaluation

There is no one way to organize the examination of an infant. Experienced examiners develop individual techniques and sequences for the evaluation [Brett, 1997]. The following is a sequence that has been successful for many individuals, using a staged approach for examination of the infant.

It is important to recognize that the examination of the infant and toddler can be a challenge even for the experienced clinician. Less experienced individuals may find it almost impossible: one study of medical students reported that more than 90 percent found the neurologic examination challenging and that children were uncooperative and difficult to examine [Jan, 2007]. This discomfort appears to remain an issue when one considers that more than 50 percent of pediatricians referred more than 90 percent of patients with neurologic complaints to neurologists, and those who refer the most have the least self-confidence in their own neurologic examinations [Maria and English, 1993].

Evaluation of the Patient

Stage 1

Head

Examination of the head must be done systematically, looking for asymmetry, indentations, and protuberances. Evaluation of the fontanels and cranial sutures should be performed with gentle palpation. The dimensions of the anterior fontanel should be carefully recorded [Pedroso et al., 2008]. The examiner should determine by observation and palpation the presence of frontal bossing, bulging fontanel, sutural synostosis or diastasis (separation), and unusual head shapes such as trigonocephaly, marked dolichocephaly or brachycephaly. Positional plagiocephaly has become increasingly common with the current “back to sleep” approach, and is the most common cause of abnormal head shape; it can often be distinguished from isolated craniostenosis by prominence of the contralateral forehead, which leads to a rhomboidal appearance [Bialocerkowski et al., 2008]. Unusual masses under the scalp and gross asymmetries of the skull should be sought.

Cranial Nerves

Most of the examination of cranial nerve function of the infant and toddler can be completed by observation with minimal invasive procedures. More details concerning examination of each cranial nerve can be found in Chapter 2. Toys or colorful objects can facilitate the assessment of extraocular movements in young children. Visual fixation and pursuit will bring out nystagmus and strabismus. If the child appears uninterested in bright objects, the possibility of a visual defect or an underlying intellectual defect must be considered. Rolling eye movements and dysconjugate gaze suggest gross visual impairment. Double simultaneous stimulation (i.e., simultaneously bringing two bright objects into both temporal fields) normally causes the child to look from one object to the other; failure to take notice of one object may indicate homonymous hemianopsia. An opticokinetic tape (with repetitive bars or objects) should be drawn horizontally and then vertically across the child’s field of vision. An absent response results from lack of visual fixation or from gross impairment of vision. Unusual transient deviations of the eyes may occur in the first year of life [Echenne and Rivier, 1992].

Motor Evaluation

There is a normal developmental sequence of fine motor control as the child becomes more adept at reaching for objects. Grasping things with both hands and holding the object before the face or immediately placing it in the mouth is later superseded by transferring the object from hand to hand and manipulating the toy. The infant’s grasping skills are best demonstrated in the response to small objects. The 4–5-month-old infant is able to grasp an object with the entire hand (Figure 3-1); at 7 months the thumb and the neighboring two fingers are used (Figure 3-2); and the pincer grasp (using only the thumb and forefinger) should be present by 9–11 months (Figure 3-3). The palmar grasp reflex (i.e., obligate grasp reflex) should gradually diminish from 3–6 months of age. Teleologically, this allows the infant to develop the ability to transfer objects from hand to hand. The persistence of the obligate grasp reflex beyond 6 months of age may signal corticospinal tract dysfunction. Observation of the child’s ability to raise the arms and to abduct and adduct the arms while reaching for a proffered object provides valuable information concerning proximal muscle strength. Simultaneously, the presence of intention tremor and of the avoidance response of early athetosis may be evident. Congenital malformations of the fingers and hands from webbing to clinodactyly can be readily determined during this portion of the examination.

Fig. 3-1 Entire hand grasp of a 4-month-old infant.

(Courtesy of the Division of Pediatric Neurology, University of Minnesota Medical School.)

Fig. 3-2 Use of two fingers and thumb in the grasp of a 7-month-old infant.

(Courtesy of the Division of Pediatric Neurology, University of Minnesota Medical School.)

Fig. 3-3 Pincer grasp with the thumb and forefinger of an 11-month-old infant.

(Courtesy of the Division of Pediatric Neurology, University of Minnesota Medical School.)

The plantar response can be as important in infants as in adults. There is no consensus of opinion about the latest time at which an extensor response is a normal finding. One report found an extensor response in 50–75 percent of 1-year-old infants [Dodge, 1964]. Others claimed that the usual response in the newborn period is flexor in origin and that the initial response is flexor in 93 percent of normal infants [Hogan and Milligan, 1971]. All would agree that asymmetric extensor toe signs or extensor toe signs that persist beyond 12 months should be considered pathologic. A pathologic extensor plantar sign is indicative of upper motor neuron unit disease. Unsustained ankle clonus up to six beats is often present in the neonatal period. Ankle clonus should disappear by 2 months of age. The persistence of ankle clonus and extensor plantar response suggests upper motor neuron unit disease even in the absence of hyperreflexia.

Sensory Testing and Cutaneous Examination

Light touch can be tested by gently stroking the extremities; this should lead to a reaction with signs of recognition ranging from eye deviation and facial response to anxious withdrawal of the limbs (Figure 3-4). Application of a tuning fork often causes arrest of motion and a wide-eyed look of wonder in the child who cannot otherwise describe the feeling. Proprioception cannot be directly evaluated at this age, but observations of sitting positions, gait, and posture may provide some clues. Pain response from light application of a pin or gentle pinching should be reserved until late in the examination. The child may cry or make short, whimpering sounds. Careless use of the pin can destroy rapport with the patient and loss of confidence on the part of the caregivers.

Stage 2

Trunk, shoulder, and pelvic girdle tone and strength should be directly evaluated. The child is observed while held in vertical and horizontal suspension. A hypotonic infant often droops over the examiner’s arm when held in horizontal suspension (“the inverted comma position”). In vertical suspension, the hypotonic child may slide through the examiner’s hands. The child may be unable to maintain a standing posture when the feet are placed on the table surface – this must be distinguished from active withdrawal of the legs that may also prevent successful standing. Increased tone, or hypertonicity, usually the result of spasticity, may manifest by arching of the extended head, neck, and back) while in horizontal suspension. Extensor thrusting with legs extended and “scissoring” with excessive abduction can be seen when the child is held in vertical suspension, and the child may stand on the toes when the feet are allowed to touch the table (Figure 3-5).

Fig. 3-5 Extended legs, scissoring, toe stance, and fisting in an infant with spastic quadriplegia.

(Courtesy of the Division of Pediatric Neurology, University of Minnesota Medical School.)

Motor Performance Instruments

Through the years, several instruments have been devised that are useful for evaluating motor performance in relation to chronologic age. These instruments have provided norms for evaluating the expected rate of motor development for a number of different assessments and maneuvers [Zafeiriou, 2004]. The instruments that are most commonly used are listed in Box 3-2.

Box 3-2 Most Commonly Used Motor Performance Tools

Developmental screening tests

(Adapted from Zafeiriou DI. Primitive reflexes and postural reactions in the neurodevelopmental examination. Pediatr Neurol 2004;31:1.)

Developmental Reflexes

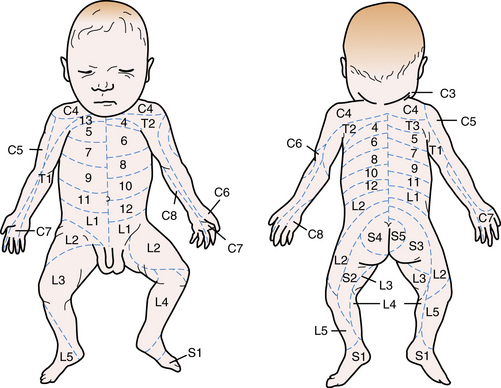

Developmental reflexes are patterned responses that are ontogenetically determined at certain ages. They represent maturational stages of the developing nervous system, and therefore they can be helpful in assessing neurologic development. Occasionally, they can have localizing value, but usually, they are non-specific. Abnormal findings include the absence or poor manifestation of the expected response, persistence of a reflex that should have disappeared, or an asymmetric response. These reflexes and the means of elicitation are listed in Table 3-1 and Table 3-2 [Zafeiriou, 2004].

| Reaction | Position | Method |

|---|---|---|

| Traction | Supine | Placing the examiner’s index finger in the infant’s hand and pulling the infant at a 45-degree angle to the examination bed |

| Horizontal suspension | Prone | Suspending the infant by placing the hands around the infant’s thorax without providing support for the head or legs |

| Vertical suspension | Vertical | Placing both hands in the axillae without grasping the thorax and lifting the infant straight up facing the examiner |

| Vojta response | Vertical | Suspension from the vertical to the horizontal position facing the examiner by placing both hands around the infant’s thorax |

| Collis horizontal suspension | Prone | Placing one hand around the upper arm and the other around the upper leg and suspending the infant in the horizontal position, parallel to the examination bed |

| Collis vertical suspension | Prone | Placing one hand around the upper leg and suspending the infant in the vertical position with the head directed downward |

| Peiper–Isbert vertical suspension | Prone | Placing the examiner’s hands around the upper leg of the infant and suspending the infant in the vertical position with the head directed downward |

(Data from Vojta, 1988; Zafeiriou et al., 1998; Zafeiriou, 2004.)

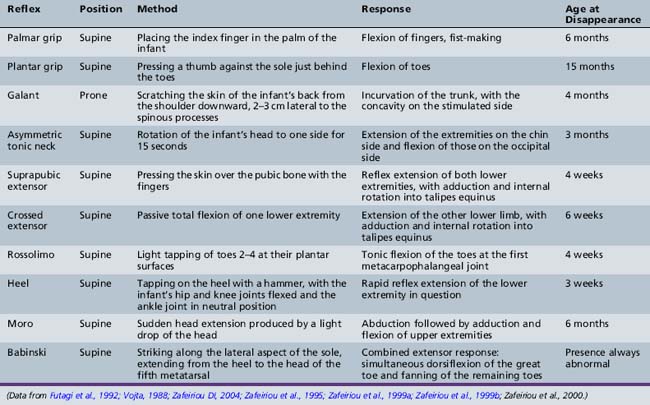

The Moro reflex presents in an incomplete fashion with an attenuated adduction phase at 2 months, and is seen in its complete fashion until 5 or 6 months of age. Although the Moro reflex may be demonstrated by different maneuvers, correctly eliciting it requires holding the infant in the supine position, lifting the head and then allowing it to fall approximately 30 degrees while cradling the head in the examiner’s hands [Parmelee, 1964]. The expected response is initial extension and abduction of the arms with extension of the fingers, followed by adduction of the arms at the shoulder (Figure 3-6). An abnormal Moro reflex usually represents diffuse central nervous system depression, generalized weakness, or severe spasticity rather than a specific area of involvement. An asymmetric Moro reflex can be caused by unilateral brachial plexus palsy, fractures of the humerus or clavicle, or spastic hemiplegia. An exaggerated Moro reflex may indicate pathologic central nervous system (CNS) irritability. The Moro reflex can be distinguised from similarly presenting extensor infantile spasms since the normal developmental reflex is always associated with a postural change and never occurs spontaneously or in clusters.

The asymmetric tonic neck reflex (ATNR) may be detected in the neonatal period but reaches its peak at 2 months. It gradually diminishes and is absent by 6 months of age. The tonic neck reflex has been described in great detail in animals and humans [Shevell, 2009]. To elicit the reflex, the head is turned to one side while the infant is lying in the supine position. There is extension of the arm and leg on the side toward which the face is turned, while the contralateral extremities flex (“fencer’s posture”). The degree of response varies widely but is usually seen to the same degree in each direction. In any event, a normal infant should not maintain the position beyond a few seconds (i.e., obligate ATNR). This reflex should disappear by 6 months of age [Paine et al., 1964]. When the ATNR can only be elicited to one side, it may indicate a lesion in the hemisphere opposite the direction in which the face is turned. The same consideration holds true if the response is obligate or persists beyond the expected age. Severe muscle weakness secondary to central or peripheral motor unit involvement may lead to an abnormally diminished response. Athetoid and spastic infants may also have an exaggerated response, and this may contribute to their difficulty in sitting or standing.

In slightly older infants, the Landau reflex can be first elicited between 5 and 10 months of age, and can usually be seen up to 2 years of age. With one hand supporting the abdomen in the prone position, the examiner flexes the infant’s head with his other hand. The normal response is flexion of the legs and trunk. When held in horizontal suspension, 55 percent of infants spontaneously elevate their heads above the horizontal plane by age 5 months and 95 percent by 6 months [Paine et al., 1964].

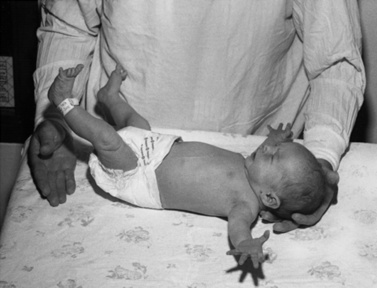

One of the most useful maneuvers is the traction response. This is elicited with the infant in the supine position; the examiner grasps both hands and pulls the infant gently and slowly upward, to a sitting position. Marked head lag with little resistance to the examiner’s pulling efforts characterizes the newborn response (Figure 3-7). By 1 month, the infant’s head shows transient neck flexion followed by extension as the infant is pulled forward. Usually, by 3–5 months of age at the latest, the infant is able to participate actively with arm flexion at the elbow, as well as holding the head and trunk in a straight line as the examiner pulls him or her to the upright position. At this point there should be no head lag, and little or no forward motion of the head as the child reaches the upright position. Asymmetry signals a neurologic difficulty. Superimposition of leg extension with standing as the infant is pulled to sitting suggests bilateral corticospinal tract difficulty.

Fig. 3-7 The traction maneuver causes little response in a 2-day-old infant.

There is little or no perceptible flexion of the neck or the arms at the elbows.

A stereotypic “elbowing” movement in newborns has been described. A curved wooden model of an ultrasonographic probe is gently used to exert pressure on the right and left subcostal regions. The newborn reacts with a particular defensive arm movement in which there is a three-phase response [Saraga et al., 2007].

Stage 3

Examination of the optic fundi should be performed with the infant supine, possibly lying in the caregiver’s lap or held over the caregiver’s shoulder with the infant’s head held tightly against the caregiver’s head. Abnormalities of the fundi, including vascular changes, elevation of the optic disc, and retinal changes, as well as abnormalities of the lens and media, should be assessed (see Chapter 6). Mydriatic agents and sedation are rarely employed in the office evaluation, although they are both occasionally necessary. During the first few months of life, the optic discs may be somewhat gray. This normal finding should not be confused with optic atrophy. Retinal abnormalities that can be seen during a routine fundoscopic examination include hypoplasia, papilledema, chorioretinitis and retinitis pigmentosa.

Stage 4

The crawling child should be put on a carpeted floor or a suitable pad; if the child stands, or walks, he or she should be placed on the floor. The child should be allowed to ambulate or encouraged by rolling a ball across the room or having him follow a parent across the room. Spastic diparesis, hemiplegia, waddling, footdrop, limp, or ataxia may be evident. The manner in which the child stoops and bends to retrieve a ball or block may show premature hand dominance, athetosis, tremor, or weakness of the legs. Whenever there is a question of proximal weakness, the child should be observed when arising from the floor to a standing position to determine the presence of Gowers’ maneuver (see Figure 2-11).

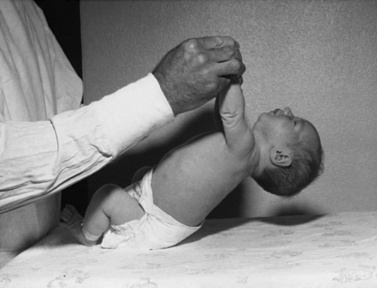

Further examination of muscle strength can be accomplished by using the parachute response; the examiner holds the child in the prone position over an examining table and gently thrusts the patient toward the table surface. A fully developed response (expected at 8 months) consists of arm and wrist extension, allowing the outstretched palms to make contact with the table as the infant supports the body weight with arms and shoulders. Each upper extremity can be tested individually if one arm is pulled from the table by the examiner, forcing the child to support most of the body weight on the opposite arm and shoulder. Somewhat older infants may be induced to support their weight on their hand as they move forward in the “wheelbarrow” maneuver (Figure 3-8) (see Chapter 2). The child should then be asked to crawl. Formal individual muscle testing can be used in the older child whenever necessary.

Fig. 3-8 Abnormal parachute response.

(Courtesy of the Division of Pediatric Neurology, University of Minnesota Medical School.)

The sensory examination is difficult and is usually limited to rather gross evaluation of touch and pain; however, much can be accomplished with persistence and patience (Box 3-3). Examination of touch, position sense, and vibration sense should be done first. When a tuning fork is placed on the appropriate bony prominence, a look of surprise or bemusement appears. Evaluation of pain should be done last and only after the examiner demonstrates to the child the method that will be used.

Box 3-3 Tips for Examining Poorly Cooperative Children

[Jan, 2007].

The older child should be asked to stand in one place with the feet together and then asked to close the eyes to be evaluated for Romberg’s sign. The examiner should observe the child for titu-bation, nystagmus, and dysmetria while reaching for objects. Cooperative children older than 3 years should be able to perform finger-nose testing with eyes closed. The heel-shin test is frequently not possible in children younger than 4 years. Many of the maneuvers suggested in Chapter 2 for the older child are applicable, depending on the maturity and abilities of the older infant.

General Considerations

Throughout the examination, the clinician should evaluate the child’s alertness, interest in the surroundings, and ability to learn during the examination. The child’s speech pattern should also be assessed. By 15 months of age, the child should have a consistent vocabulary of 2–6 words; by 18 months, up to 20 words. Short phrases consisting of two or three words are usually part of the child’s repertoire by 21–24 months. By 2 years of age, most children have a vocabulary of up to 50 words. Using specific scales to evaluate intelligence and development levels is of some help but a single office assessment may not be reliable. It is therefore important that the examiner become proficient in informal means of evaluating these characteristics. A new website, PediNeuroLogicExam (http://library.med.utah.edu/pedineurologicexam/html/download_by_exam.html), provides text and movies demonstrating the changing examination as the child matures, along with an approach to examining the young patient.

References

![]() The complete list of references for this chapter is available online at www.expertconsult.com.

The complete list of references for this chapter is available online at www.expertconsult.com.

Amiel-Tison C. Neurological evaluation of the maturity of newborn infants. Arch Dis Child. 1968;43:89.

Amiel-Tison C. Update of the Amiel-Tison neurologic assessment for the term neonate or at 40 weeks’ corrected age. Pediatr Neurol. 2002;27:196.

Bayley N. The Bayley scales of infant development. New York: The Psychological Corporation, 1969.

Bialocerkowski A.E., Vladusic S.L., Ng C.W. Prevalence, risk factors, and natural history of positional plagiocephaly: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50:577.

Brazelton T., Nugent K. Neonatal Behavior Assessment Scale, ed 3. London: MacKeith Press, 1995.

Brett E.M. Normal development and neurological examination beyond the newborn period. In Brett E.M., editor: Paediatric Neurology, ed 3, London: Churchill Livingstone, 1997.

Campbell S., Osten E., Kolobe T., et al. Development of the test of infant motor performance. Phys Med Rehabil Clin. 1993;4:541.

Dargassies S.S. Neurological development in the full term and premature neonate. New York: Excerpta Medica, 1997.

Dodge P.R. Neurologic history and examination. In: Farmer T.W., editor. Pediatric Neurology. New York: Paul B. Hoeber, Medical Book Department of Harper & Brothers, 1964.

Dubowitz L.M.S., Dubowitz V., Mercuri E. The neurological assessment of the preterm and full-term infant, ed 2. London: MacKeith Press, 1999.

Echenne B., Rivier E. Benign paroxysmal tonic upward gaze. Pediatr Neurol. 1992;8:154.

Frankenburg W.K., Sciarillo W., Burgess D. The newly abbreviated and revised Denver Developmental Screening Test. J Pediatr. 1981;99:995.

Frankenburg W.K., Dodds J., Archer P., et al. The Denver II: A major revision and restandardization of the Denver Developmental Screening test. Pediatrics. 1992;89:91.

Futagi Y., Tagawa T., Otani K. Primitive reflex profiles in infants: Differences based on categories of neurological abnormality. Brain Dev. 1992;14:294.

Gesell A., Amatruda C.S. Developmental diagnosis. New York: Paul B. Hoeber, Medical Books Department of Harper & Brothers, 1956.

Glascoe F.P., Byrne K.E. The Usefullness of the Battelle Developmental Inventory Screening Test. Clin Paediatr (Phila). 1999 May;32(5):273-280.

Haataja L., Mercuri E., Regev R., et al. Optimality score for the neurological examination of the infant at 12 and 18 months of age. J Pediatr. 1999;135:153.

Hogan G.R., Milligan J.E. The plantar reflex of the newborn. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:502.

Illingsworth R.S. The development of the infant and young child, ed 9. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1987.

Jan M.M. Neurological examination of difficult and poorly cooperative children. J Child Neurol. 2007;22:1209.

Kaye L., Whitfield M.F. The eighth month movement assessment of infants as a prediction of cerebral palsy in high-risk infants (Abstract). Dev Med Child Neurol. 1988;30(Suppl. 57):11.

Knobloch H., Stevens F., Malone A. The Revised Developmental Screening Inventory. Houston, Texas: Gesell Developmental Test Materials, 1980.

Leppert M.L.O., Shank T.P., Shapiro B.K., et al. The Capute Scales: CAT/CLAMS–tool for the early detection of mental retardation and communicative disorders. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 1998;4:14.

Maria B.L., English W. Do pediatricians independently manage common neurological problems? J Child Neurol. 1993;8:73.

Morgan A. Early diagnosis of cerebral palsy using a profile of abnormal motor patterns. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1988;30(Suppl. 57):12.

Paine R.S., Brazelton T.B., Donovan D.E. Evolution of postural reflexes in normal infants and in the presence of chronic brain syndromes. Neurology. 1964;14:1036.

Parmelee A.H.Jr. A critical evaluation of the Moro reflex. Pediatrics. 1964;33:773.

Piper M.C., Pinnell L.E., Darrah J., et al. Construction and validation of the Alberta Infant Motor Scale (AIMS). Can J Public Health. 1992;83(Suppl. 2):46.

Prechtl H., Beintema D. Neurological examination of the full term infant. London: Heinemann, 1964.

Prechtl H.F. State of the art of a new functional assessment of the young nervous system. An early predictor of cerebral palsy. Early Hum Dev. 1997;24:1.

Prechtl H.F., Eisenpieler C., Cioni G., et al. An early marker for neurological deficits after perinatal brain lesions. Lancet. 1997;349:1361.

Reed H. Review of Peabody developmental motor scales and activity cards. In: Mitchell J., editor. The ninth mental measurements yearbook. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 1985:1119.

Russell D., Rosenbaum P.L., Avery L.M., et al. Gross Motor Function Measure (GMFM-66 and GMFM-68). User’s manual. London: MacKeith Press, 2002.

Saraga M., Resić B., Krnić D., et al. A stereotypic “elbowing” movement, a possible new primitive reflex in newborns. Pediatr Neurol. 2007;36:84-87.

Vojta V. Die cerebralen Bewegungstoerungen im Kindesalter, 4te Auflage. Stuttgart: Ferdinand Enke Verlag, 1988.

Zafeiriou D.I. Plantar grasp reflex in high-risk infants at the first year of life. Pediatr Neurol. 2000;22:75.

Zafeiriou D.I. Primitive reflexes and postural reactions in the neurodevelopmental examination. Pediatr Neurol. 2004;31:1.

Zafeiriou D.I., Tsikoulas I.G., Kremenopoulos G.M. Prospective follow-up of primitive reflex profiles in high-risk infants: Clues to an early diagnosis of cerebral palsy. Pediatr Neurol. 1995;13:148.

Zafeiriou D.I., Tsikoulas I., Kremenopoulos G., et al. Using postural reactions as a screening test to identify high-risk infants with cerebral palsy: A prospective study. Brain Dev. 1998;20:307.

Zafeiriou D.I., Tsikoulas I., Kremenopoulos G., et al. Moro reflex profile in high-risk infants at the first year of life. Brain Dev. 1999;21:216.

Zafeiriou D.I., Tsikoulas I., Kremenopoulos G., et al. Plantar response profile of high-risk infants at the first year of life. J Child Neurol. 1999;14:514.

Dodge H.W. Cephalic bruits in children. J Neurosurg. 1956;13:527.

Egan D.F. Developmental examination of infants and preschool children. Clinical developmental medicine. Oxford: MacKeith Press; 1990;112.

Fenichel G.M. Clinical pediatric neurology: A signs and symptoms approach, ed 3. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1997.

Hack M., Mostow A., Miranda S.B. Development of attention in preterm infants. Pediatrics. 1976;58:669.

Haymaker W. Bing’s local diagnosis in neurological diseases, ed 15. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1969.

Kamin D.F., Hepler R.S., Foos R.Y. Optic nerve drusen. Arch Ophthalmol. 1973;89:359.

Keegan J.J., Garrett F.D. The segmental distribution of the cutaneous nerves in the limbs of man. Anat Rec. 1948;102:409.

Kestenbaum A. Clinical methods of neuro-ophthalmologic examination. New York: Grune & Stratton, 1961.

Knobloch H., Pasamanick B. Predicting intellectual potential in infancy. Am J Dis Child. 1963;166:43.

Korobkin R. The relationship between head circumference and the development of communicating hydrocephalus following intraventricular hemorrhage. Pediatrics. 1975;56:74.

Lubchenco L.O., Hansman M., Boyd E. Intra-uterine growth in length and head circumference as estimated from live births at gestational ages from 26 to 42 weeks. Pediatrics. 1966;37:403.

Miller G., Heckmatt J.Z., Dubowitz L.M.S., et al. Use of nerve conduction velocity to determine gestational age in infants at risk and in very-low-birth-weight infants. J Pediatr. 1983;103:109.

Moosa A., Dubowitz V. Assessment of gestational age in newborn infants: Nerve conduction velocity versus maturity score. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1972;14:290.

Nellhaus G. Composite international and interracial graphs. Pediatrics. 1968;41:106.

Nelson K.B., Eng G.D. Congenital hypoplasia of depressor anguli oris muscle: Differentiation from congenital facial palsy. J Pediatr. 1972;81:16.

O’Neill E. Normal head growth and prediction of head size in infantile hydrocephalus. Arch Dis Child. 1961;36:241.

Paine R.S. Neurologic conditions in the neonatal period: Diagnosis and management. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1961;8:577.

Paine R.S., Oppe T.E. Neurological examination of children. London: William Heinemann Medical Books, 1966.

Pedroso F.S., Rotta N., Quintal A., et al. Evolution of the anterior fontanel size of normal infants in the first year of life. J Child Neurol. 2008;23:1419.

Peiper A. Cerebral function in infancy and childhood. New York: Consultants Bureau Enterprises, 1963.

Prechtl H.F.R. The neurological examination of the full term newborn infant, ed 2. London: William Heinemann Medical Books, 1977.

Robinson R.J. Assessment of gestational age by neurologic examination. Arch Dis Child. 1966;41:437.

Sauer C., Levinsohn M.W. Horner’s syndrome in childhood. Neurology. 1976;26:216.

Scher M.S., Barmada M.A. Gestational age by electrographic, clinical, and anatomical criteria. Pediatr Neurol. 1987;3:256.

Shevell M. The tripartite origins of the tonic neck reflex: Gesell, Gerstmannn, and Magnus. Neurology. 2009;72:850.

Sonksen P.M. The assessment of vision in the preschool child. Arch Dis Child. 1993;68:513.

Volpe J.J. The neurological examination: normal and abnormal features. In Volpe J.J., editor: Neurology of the newborn, ed 5, Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2008.

Volpe J.J., Pasternak J.F., Allan W.C. Ventricular dilation preceding rapid head growth following neonatal intracranial hemorrhage. Am J Dis Child. 1977;131:1212.