50

Neurofibromatosis and Tuberous Sclerosis

Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (von Recklinghausen Disease)

• Incidence of approximately 1 in 3000 births.

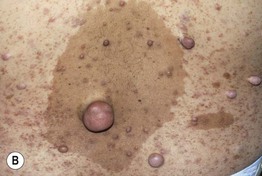

• The major clinical features of NF1 are outlined in Table 50.1 and depicted in Figs. 50.1–50.5; Fig. 50.6 shows the time course of their development.

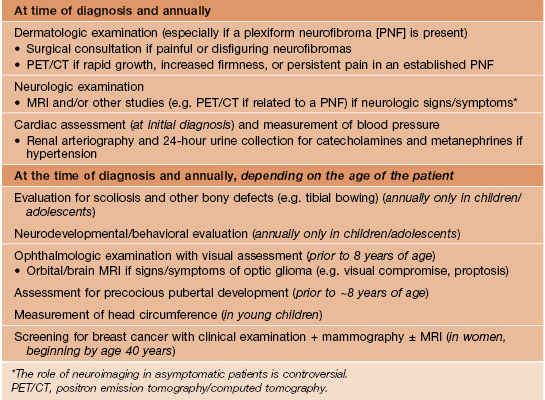

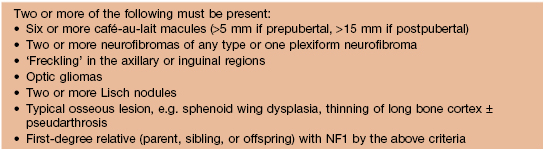

Table 50.1

Major clinical features of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1).

ADD, attention deficit disorder; GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumors; GU, genitourinary; JMML, juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia.

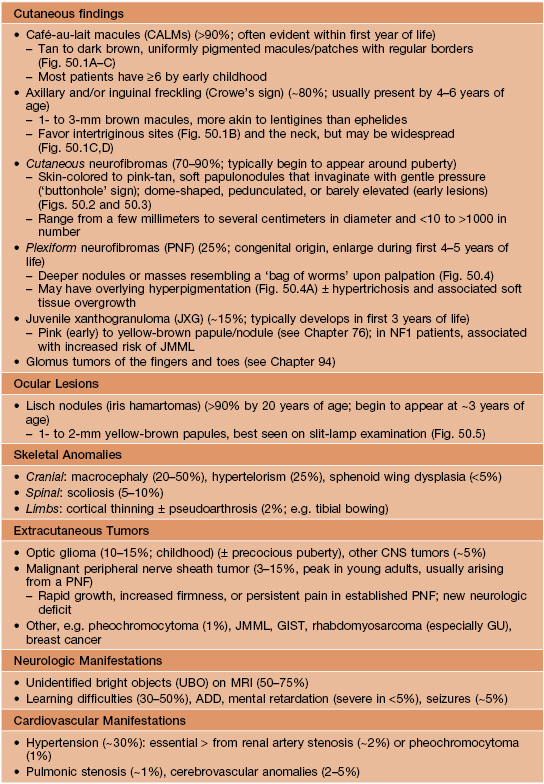

Fig. 50.1 Café-au-lait macules and ‘freckling’. Oval-shaped, light-to medium-brown patches with regular borders and uniform pigmentation (A, B). Numerous 1- to 3-mm lentigines are most commonly found in the axilla (Crowe’s sign) (B) but can also develop in other sites such as the perioral region (C). A, C, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

Fig. 50.2 Multiple cutaneous neurofibromas. Soft, skin-colored to pinkish tan, dome-shaped or polypoid, well-demarcated papules and nodules of various sizes (A, B) in patients with NF1. Neurofibromas may be superimposed on café-au-lait macules and lentigines (B). Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

Fig. 50.3 Spectrum of cutaneous neurofibromas. Lesions range from subtle blue-red macules (A) to exophytic nodules with associated hypertrichosis (B). Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

Fig. 50.4 Plexiform neurofibromas. A A hyperpigmented plaque that may be misdiagnosed as a congenital melanocytic nevus or (if not palpated) a café-au-lait macule. Note the widespread ‘freckling’ on the trunk. B A poorly circumscribed, sagging pink mass. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

Fig. 50.6 Development of clinical features in neurofibromatosis type 1. The time course of major diagnostic lesions that develop in NF1. During the first few years of life, a child may have only café-au-lait macules. Adapted from DeBella K, Szudek J, Friedman JM. Use of the National Institutes of Health criteria for diagnosis of neurofibromatosis 1 in children. Pediatrics 2000;105:608–614.

• The NIH diagnostic criteria for NF1 (Table 50.2) are met in 97% of patients by age 8 years.

Table 50.2

Classic diagnostic criteria for neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1).

Reproduced with permission from NIH Conference: Neurofibromatosis Statement. Arch. Neurol. 1988;45:575–578.

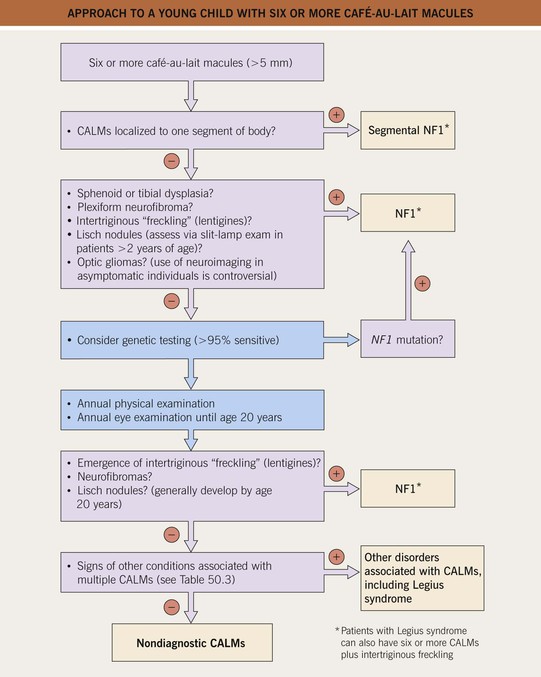

• An approach to infants or young children with ≥6 CALMs is presented in Fig. 50.7.

Fig. 50.7 Approach to a young child with six or more café-au-lait macules (CALMs). More than half of these patients will eventually be diagnosed with NF1 or, less often, another CALM-associated syndrome (see Table 50.3). The latter should be considered if other signs of NF1 do not develop.

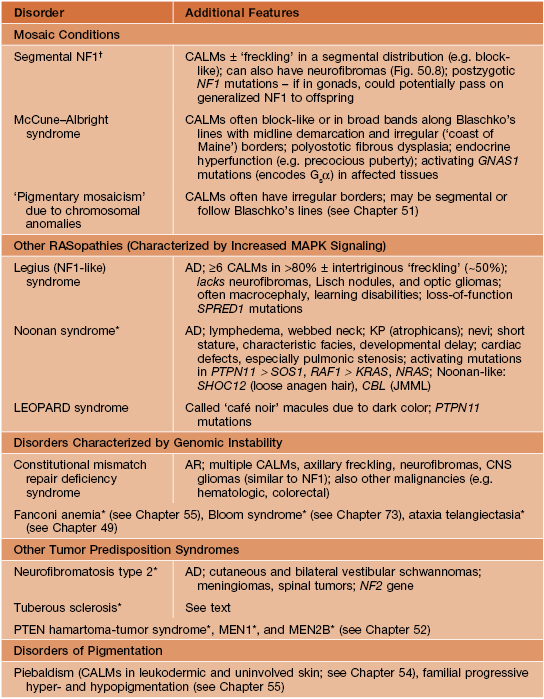

• DDx: other disorders that can manifest with multiple CALMs are summarized in Table 50.3.

Table 50.3

Other disorders associated with multiple café-au-lait macules (CALMs).

Of note, approximately 30% of the general population has at least one CALM.

† DDx may include a large speckled lentiginous nevus (nevus spilus) or partial unilateral lentiginosis (see Chapter 92).

* Multiple CALMs in small minority of affected individuals.

AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; JMML, juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia; KP, keratosis pilaris; LEOPARD, lentigines/electrocardiogram abnormalities/ocular hypertelorism/pulmonary stenosis/abnormalities of genitalia/retardation of growth/deafness syndrome; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; NF1, neurofibromatosis type 1.

Fig. 50.8 Segmental neurofibromatosis. A cluster of soft, pink to pink-brown papules limited to the thigh. There were no associated café-au-lait macules. Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

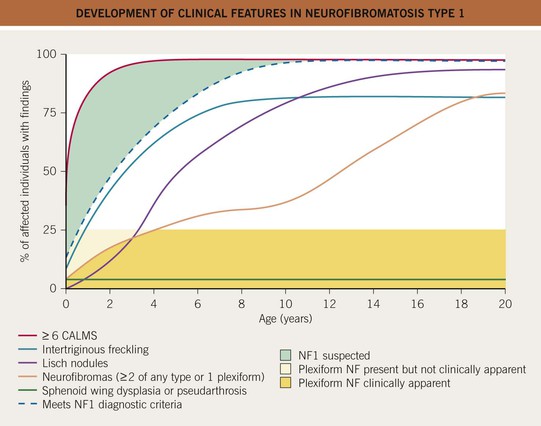

• Management of NF1 requires a multidisciplinary approach (Table 50.4).

Tuberous Sclerosis

• Incidence of approximately 1 in 10 000 births.

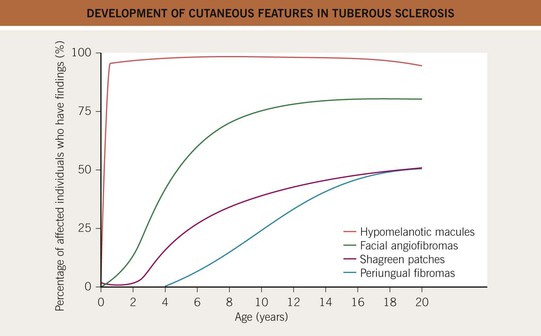

• Fig. 50.9 shows the time course for the development of cutaneous findings in TS.

Fig. 50.9 Development of cutaneous features in tuberous sclerosis. Hypomelanotic macules are usually the only cutaneous finding at birth.

• The hypomelanotic macules in TS patients vary in number (few to >100) and size (<1 to >10 cm); their shapes are polygonal more often than resembling an ‘ash leaf’ – rounded at one end, tapered at the other (Fig. 50.10A).

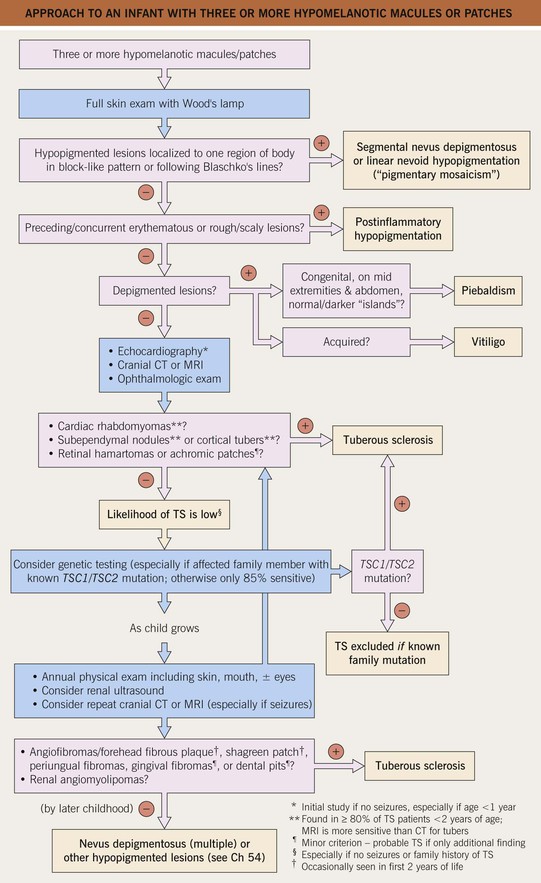

– DDx: nevus depigmentosus is a common (1–5% of healthy children) cause of one or two hypopigmented macule(s) or patch(es); Fig. 50.11 presents an approach to infants/young children with ≥3 hypomelanotic macules.

Fig. 50.10 Hypopigmentation in tuberous sclerosis. A Ash leaf macule. B ‘Confetti’ macules of guttate leukoderma. B, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

Fig. 50.11 Approach to an infant with three or more hypomelanotic macules or patches. A child with fewer than three macules and no family history of tuberous sclerosis (TS) has an extremely low likelihood of having this disease.

• Numerous small, confetti-like hypopigmented macules (especially on the extremities) represent a relatively specific finding for TS (Fig. 50.10B).

• Angiofibromas (formerly known as ‘adenoma sebaceum’) are smooth, dome-shaped, pink to red-brown papules (Fig. 50.12); they favor the central face and sometimes coalesce to form plaques.

– DDx: multiple facial angiofibromas can occur in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) and Birt–Hogg–Dubé syndrome (see Chapter 91).

Fig. 50.12 Facial angiofibromas. Multiple shiny, dome-shaped papules on the cheeks and nose of an adolescent. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• Variants of angiofibromas include cephalic fibrous plaques (e.g. on forehead), ungual fibromas (Koenen tumors; toes > fingers) (Fig. 50.13), and molluscum pendulum (resembling large skin tags) in flexural sites.

Fig. 50.13 Periungual fibromas of tuberous sclerosis. Multiple fibromas of the toes arising in a periungual location.

• Shagreen patches are connective tissue nevi with a predilection for the lower back; they present as skin-colored, hyperpigmented or (less often) hypopigmented plaques with an uneven, pigskin-like surface (Fig. 50.14).

Fig. 50.14 Connective tissue nevi (shagreen patches) in tuberous sclerosis. These plaques can be hyperpigmented (A) or hypopigmented (B) relative to the patient’s background skin. The surface is said to resemble leather or pigskin. B, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

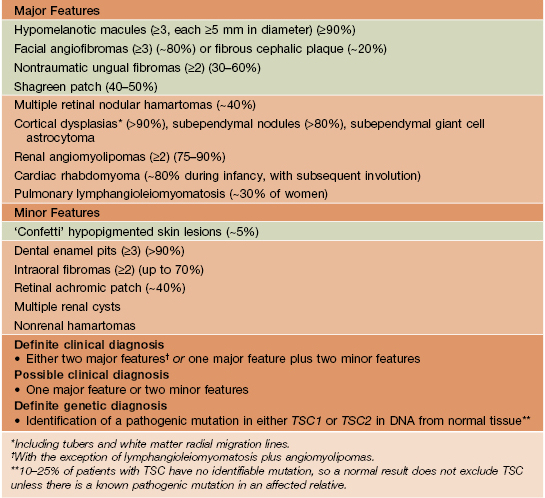

• Additional extracutaneous manifestations and diagnostic criteria are listed in Table 50.5.

Table 50.5

Revised diagnostic criteria for tuberous sclerosis complex.

In contrast to NF1, café-au-lait macules are found in a minority of patients and are usually few in number. Green background = cutaneous lesions.

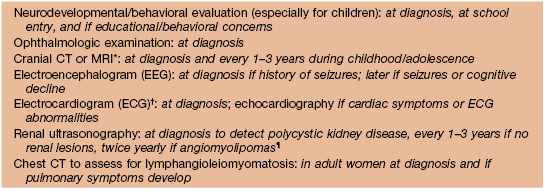

• Recommendations for evaluation and management are presented in Table 50.6.

Table 50.6

Evaluation and management of tuberous sclerosis patients.

* Findings may correlate with seizure activity and cognitive deficits; assess for enlarging lesions suggestive of giant cell astrocytomas (most common during childhood).

† Arrhythmias are more common in patients with TS than the general population.

¶ Angiomyolipomas >3.5–4 cm in diameter should be assessed with CT or MRI.

For further information see Ch. 61. From Dermatology, Third Edition.