Opioids were first introduced into the central neuraxis in 1979. Since that time, epidurally and intrathecally administered opioids have been used for both acute and chronic pain control and are commonly administered in combination with other neuraxial adjuvant compounds, such as local anesthetics and α2-adrenoreceptor agonists. The clinical benefits of epidural and intrathecal opioids include excellent analgesia in the absence of motor, sensory, and autonomic blockade. Downstream benefits then occur, which include earlier ambulation and improved pulmonary function.

The sites of action are the opioid receptors found mainly within layers 4 and 5 of the substantia gelatinosa in the dorsolateral horn of the spinal cord. When activated, these receptors inhibit the release of excitatory nociceptive neurotransmitters within the spinal cord. In addition to producing direct spinal effects, neuraxially administered opioids may also activate cerebral opioid receptors when cephalad spread of the drug occurs via cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Systemic effects may also be seen because some drug is absorbed into the vasculature.

The lipid solubility of each opioid, determined by the octanol/water partition coefficient, is the most critical pharmacokinetic property to consider when administering opioid doses near the neuraxis. Molecular weight, dose, and volume of injectate may also play a role in dural transfer (Table 212-1).

Table 212-1

Octanol/Water Partition Coefficients and Molecular Weights of Common Opioids

| Drug |

Octanol/Water Partition Coefficient |

Molecular Weight (g/mol) |

| Morphine |

1.4 |

285 |

| Hydromorphone |

2 |

285 |

| Meperidine |

39 |

247 |

| Alfentanil |

145 |

452 |

| Fentanyl citrate |

813 |

528 |

| Sufentanil citrate |

1778 |

578 |

Hydrophilic opioids (those with low octanol/water partition coefficients, e.g. morphine) have a high degree of solubility within the CSF, permitting significant cephalad spread. Therefore, thoracic analgesia may be accomplished when either epidural or intrathecal doses are administered at the lumbar level. The epidural or intrathecal dose of morphine is significantly less than that required to achieve an equianalgesic effect through intravenous administration.

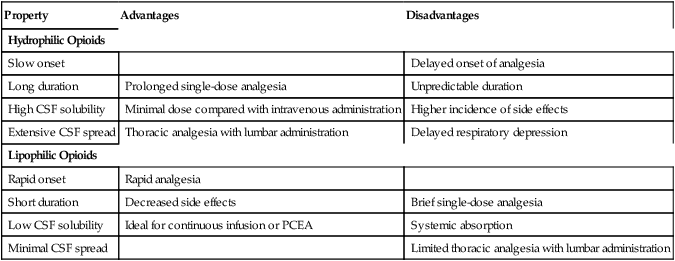

Hydrophilic opioids, used epidurally (Table 212-2), have a slow onset and prolonged duration of action. An initial epidural bolus dose is required, which may be followed by a continuous infusion through an epidural catheter. Because of their slow onset of action, hydrophilic opioids are less suitable for patient-controlled epidural analgesia than are lipophilic opioids. When hydrophilic opioids are used intrathecally, onset of action is more rapid and very low doses are required, resulting in less systemic toxicity. Effective analgesia may be provided for up to 24 h. This method is less expensive because no catheter is used.

Table 212-2

Clinical Pharmacology of Epidural Opioids*

| Property |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

| Hydrophilic Opioids |

| Slow onset |

|

Delayed onset of analgesia |

| Long duration |

Prolonged single-dose analgesia |

Unpredictable duration |

| High CSF solubility |

Minimal dose compared with intravenous administration |

Higher incidence of side effects |

| Extensive CSF spread |

Thoracic analgesia with lumbar administration |

Delayed respiratory depression |

| Lipophilic Opioids |

| Rapid onset |

Rapid analgesia |

|

| Short duration |

Decreased side effects |

Brief single-dose analgesia |

| Low CSF solubility |

Ideal for continuous infusion or PCEA |

Systemic absorption |

| Minimal CSF spread |

|

Limited thoracic analgesia with lumbar administration |

CSF, Cerebrospinal fluid; PCEA, patient-controlled epidural analgesia.

*Modified from Grass JA. Epidural analgesia. Probl Anesth. 1998;10:45-70.

Lipophilic opioids (those with a high octanol/water partition coefficient, e.g., fentanyl) have a rapid onset and a much shorter duration of action. When used epidurally (see Table 212-2), these drugs are rapidly taken up by epidural fat and redistributed into the systemic circulation, resulting in poor bioavailability to the spinal cord. Neuraxial doses of lipophilic opioids needed to achieve equianalgesic effect are nearly equal to intravenous doses. Plasma levels attained with equal doses of epidural and intravenous infusions of fentanyl are nearly identical, suggesting a significant systemic mode of action. Low CSF solubility permits only a limited amount of cephalad spread. Doses should be placed near the dermatome or dermatomes at which analgesia is desired. Therefore, lumbar administration of a lipophilic opioid would be a poor choice for thoracic analgesia. Side effects are generally fewer, with a lower incidence of delayed respiratory depression. These drugs are ideal for continuous infusions and patient-controlled epidural analgesia.

Epidural doses of hydrophilic opioids produce a biphasic pattern of respiratory depression. A portion of the initial bolus dose is absorbed systemically, accounting for the initial phase, and usually occurs within 2 h of the bolus dose being administered. Remaining drug within the CSF slowly spreads rostrally, producing a second phase as the drug reaches the brainstem 6 to 18 h later, resulting in direct depression of the respiratory nuclei and chemoreceptors. Intrathecal doses of hydrophilic opioids produce only a uniphasic pattern of respiratory depression. Effective doses of intrathecally administered hydrophilic opioid are very low compared with the larger epidural doses, and early respiratory depression is typically not seen. The slow rostral spread of drug deposited directly within the CSF is responsible for the pattern of delayed respiratory depression. Mechanical ventilation and Valsalva maneuvers (coughing/vomiting) that raise intrathoracic pressure may promote rostral spread. Somnolence usually precedes the onset of significant respiratory depression. Patients should be closely monitored; monitoring should include continuous pulse oximetry for the 24-h period following a neuraxial dose of morphine. If an infusion is planned, monitoring is necessary throughout its duration.

Side effects after neuraxial administration of opioids are dose dependent and are generally similar when used either epidurally or intrathecally. They include respiratory depression, somnolence, pruritus, nausea and vomiting, and urinary retention. Generalized pruritus is the most common and least dangerous side effect seen with the use of neuraxial opioids. The mechanism is unclear, but it is not thought to be secondary to histamine release—rather, it is more likely to be brainstem mediated. Treatment includes dilute naloxone infusions and low-dose mixed agonist/antagonist opioids (nalbuphine). Antihistamines may also be beneficial for the sedation they may provide.

Nausea and vomiting are common complications of neuraxial opioid administration. They also often occur with parenteral opioid use. Reversible causes, such as hypotension, must be initially ruled out and corrected. Rostral spread of opioids directly stimulates the medullary vomiting center. Treatment options include the administration of butyrophenones (droperidol), phenothiazines (prochlorperazine), 5-HT3 antagonists (ondansetron or granisetron), and antihistamines. Phenothiazines may cause significant drowsiness, however, which may hinder evaluation of somnolence secondary to the opioid effects.

Opioids may reduce the sacral parasympathetic outflow, resulting in urinary retention. Although this may be reversed by direct antagonism with naloxone, the doses of naloxone required are often high and may also result in reversal of analgesia. Placement of an indwelling urinary catheter should be considered.