Chapter 21. Nervous System

Much of the neurologic assessment can be integrated with other areas of the assessment. Parents can be valuable aides in performing the neurologic assessment of a child because they are more aware of the child’s usual functioning. Parental concerns are important in alerting health professionals to delays, impairments, behavioral changes, and need for anticipatory guidance.

In performing the neurologic assessment, the nurse must be aware of age-appropriate levels of functioning.

Rationale

A thorough neurologic assessment is necessary whenever a child has sustained a fall, has suffered an injury to the head or spine, complains of headaches, or has a temperature of unknown origin. Children who have an apparent developmental delay or impairment and those with identified neurologic disorders should also undergo neurologic assessment. Neurologic impairment can delay a child’s development and functioning and must be identified early to minimize long-term disability.

Anatomy and Physiology

The nervous system is a complex integrated system, and its scope is beyond that of this text. Essentially the nervous system is composed of the brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nervous system. The brain is divided into the brainstem, cerebrum, and cerebellum. Except for the first cranial nerve, the cranial nerves emerge from the brainstem. The brainstem and the spinal cord are continuous. Consciousness arises from interaction between the cerebrum and brainstem. The cerebellum is primarily responsible for coordination. The full number of adult nerve cells is established midway through the prenatal period. Neurons, responsible for memory, consciousness, sensory and motor responses, and thought control, increase in size but not number after birth. Glial cells increase in both size and number until the age of 4 years. Dendrites, responsible for the transmission of impulses across synapses, increase in number and branchings. Axons increase in length. The size of the brain increases from 325 gm (11 oz) at birth to 1000 gm (2.2 lb) by 1 year of age (the adult brain weighs 1400 gm, or approximately 3 lb). Myelinization, begun in the fourth month of gestation, progresses throughout early infancy and childhood, until the child is able to move voluntarily and to engage in higher cortical functions. The order in which myelinization occurs corresponds to the normal sequence of development.

Equipment for Assessment of Nervous System

▪ Two safety pins

▪ Closed jars containing solutions with distinctive odors

▪ Cotton balls

▪ Reflex hammer

Preparation

Ask whether there is a family history of genetic disorders, learning disorders, or birth defects. Inquire whether the mother had difficulties during pregnancy or delivery. Ask the parent about prenatal history, consumption of drugs (such as alcohol, cocaine, heroin, and marijuana) during pregnancy, type of delivery, birth weight of the infant or child, and whether the infant or child had problems after birth. Ask whether the child has or has had recurrent headaches, neck stiffness, seizures, irritability, or hyperactivity. If the child has sustained an injury, determine the time of occurrence, the events surrounding the injury, the area of impact, whether consciousness was lost, and memory loss for events just before or after the injury. If concussion has been sustained, inquire about symptoms of postconcussion syndrome (PCS) (see box on p. 311).

Assessment of Mental Status

Mental status can be assessed formally and informally throughout the examination and includes intellectual or cognitive functioning, thought and perceptions, mood, appearance, and behavior (see Chapter 24 for a more detailed discussion of assessment of mental health). Intellectual functioning can be formally assessed through the use of the Denver Developmental Screening Test II (Denver II) (see Chapter 22), which is administered at specified intervals in some agencies but can be administered anytime a problem is suspected. Illness, injury, a strange environment, cultural and language differences, and the examiner’s approach can all influence intellectual functioning, mood, and understanding, so the nurse should compare findings against the parent’s observations of the child’s behavior.

| Assessment | Findings | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Level of Consciousness (LOC) | |||

|

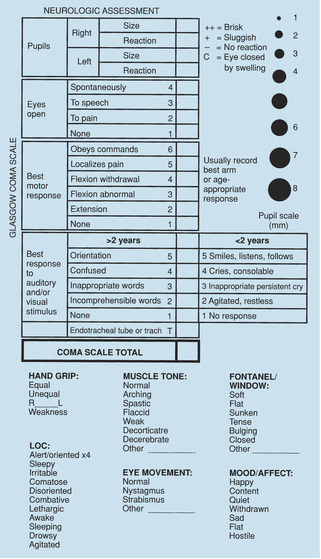

Level of consciousness remains the most reliable and earliest indicator of changes in neurologic status and is a less variable indicator than vital signs, reflexes, and motor activity. LOC can be assessed using a pediatric version of the Glasgow Coma Scale (Figure 21-1).

Responses in each category are rated on a scale from 1 to 5. Whenever possible, have a parent present because a child might not respond actively to an unfamiliar person in an unfamiliar environment. It is also important to ask the parent about the child’s normal level of responsiveness.

|

Normal children will score 15 on the Glasgow Coma Scale.

Clinical Alert

A score of 8 or less on the Glasgow Coma Scale indicates coma.

A variety of drugs affect pupil size and reaction to light. Pupils are pinpointed and fixed with narcotic ingestion; they are dilated and reactive to light with central nervous system stimulants and hallucinogens.

Photophobia occurs with bacterial meningitis, PCS, and some infectious diseases.

|

||

| Posttraumatic Amnesia (PTA) | |||

| If traumatic brain injury has occurred, recall of events before and after the event can be useful in assessing the extent of the injury. In concussion, this information is included in a variety of grading systems (Table 21-1). Inquire about the child’s memory of the event (e.g., “Tell me what happened. What were you doing just before that? After that?”). | |||

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Memory and Orientation | |

| Assess memory and orientation by asking the child for his or her name; city or town of residence; grade or birth date; and day, time, and year (older children). With athletes, studies suggest it might be more useful to ask questions that assess short-term memory, such as “What period were we in?” “What rink are we at?” and “Which side scored the last goal?” |

Clinical Alert

Cognitive function remains relatively intact in sports-related concussions; assessment of general orientation is therefore less sensitive than for other head injuries. Questions of short-term memory are more sensitive with sports-related injuries.

Headache and confusion may be the presenting symptoms in athletic related head injuries.

Athletes may not recognize that they have had a head injury or may be reluctant to report symptoms for fear of not being able to participate in sport.

|

| Posture and Motor Behavior | |

| Assess the child’s level of activity, control of impulses, appropriateness of behavior to situation and developmental stage, repetitive movements, presence of culturally appropriate eye contact and interaction, withdrawal, cooperativeness, and argumentativeness. |

Motor behavior will vary with the age of the child and stage of development, what is acceptable within the family, and cultural norms.

Clinical Alert

Soft signs represent more primitive responses than might be expected for age and can indicate minimum brain dysfunction. Signs normally disappear with maturation. These include unusual body movement (e.g., mirroring), short attention span, easy distractibility, impulsivity, lability, hyperactivity, poor coordination, perceptual defects, learning difficulties, and language or articulation difficulties.

Hyperactivity, irritability, and diminished impulse control can indicate attention deficit disorder (ADD) or fetal alcohol syndrome.

Aggressiveness, irritability, disobedience, and emotional lability can indicate PCS when injury has occurred.

Hyperactivity, hypoactivity, and other behavioral changes can accompany the use of commonly abused drugs.

Withdrawal, diminished eye contact (unless culturally appropriate), slumped shoulders, and slowed movements can indicate depression.

Opisthotonus or hyperextension of the neck and spine, accompanied by pain on flexion of the neck, can indicate meningeal irritation or inflammation and should be immediately referred.

|

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Hygiene and Grooming | |

| Observe hygiene and grooming in older children and adolescents. Inquire if there have been changes in grooming habits lately that are of concern. |

Clinical Alert

Neglect of personal hygiene can indicate family stress, depression, PCS, fatigue related to sleep disturbances or injury, or substance abuse.

|

| Mood | |

| Observe mood and intensity of mood (see Chapter 24 for detailed assessment). | |

Motor function can be assessed during assessment of the musculoskeletal system.

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Observe the infant or child for obvious abnormalities that can influence motor functioning. Specifically, observe the size and shape of the head and inspect the spine for sacs and tufts of hair. |

Clinical Alert

A large head, enlarged frontal area, and tense fontanels (if open) can indicate hydrocephalus.

A dimple with a tuft of hair or a sac protruding from the spinal column can indicate spina bifida occulta.

A small head or microcephaly is associated with chromosomal abnormalities, prenatal exposure to toxic agents, maternal infections, and trauma during the perinatal period or infancy.

|

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Observe for handedness. |

Infants and toddlers do not display marked preference for one hand, although they might show some preference.

Clinical Alert

Singular use of one hand by a very young child can indicate paresis of the opposite side.

Failure to develop handedness in a school-age child can indicate failure of the brain to develop dominance.

|

|

Test muscle strength and symmetry by asking the child to squeeze your fingers, press soles of feet against your hands, and push away pressure exerted on arms and legs.

Place all joints through range of motion. Note flaccidity or spasticity.

|

Clinical Alert

Report any asymmetry.

Infants normally have the most flexible range of motion.

All school-age children should be able to perform these activities.

Clinical Alert

Retroflexion of the head, stiffness of the neck, and extension of the extremities accompanies the meningeal irritation of meningitis and intracranial hemorrhage.

Head lag after 4 months is an early sign of neurologic damage.

Hypotonia is associated with Down syndrome.

|

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Cerebellar function can be tested by asking the child to hop, skip, or walk heel-to-toe. A Romberg’s test can be performed by asking the child to stand still, eyes closed and arms at side. Stand near the child to catch the child if leaning occurs. |

Clinical Alert

Leaning to one side during a Romberg’s test indicates cerebellar dysfunction.

|

Assessment of Sensory Function

Sensory function is assessed during testing of cranial nerve function.

Assessment of Cranial Nerve Function

The function of most of the cranial nerves can be evaluated during other areas of the health assessment (Table 21-2). Particular attention is paid to function of the cranial nerves when neurologic impairment is possible, suspected, or actually present, and should be a routine part of assessment in a child with a head injury.

| *Some portions of function can be assessed in infants and younger children. |

||

| †Only older children can participate in testing. |

||

| Cranial Nerve | Assessment of Function | Area of Health Assessment into Which Testing Can Be Integrated |

|---|---|---|

| I Olfactory | Have the child close eyes and, blocking one nostril at a time, correctly identify distinctive odors (e.g., coffee, oranges). | Head and neck |

| II Optic* | Check the child’s visual acuity, perception of light and color, and peripheral vision. Examine the optic disk. | Eye |

| III Oculomotor* | Check pupil size and reactivity. Inspect the eyelid for position when open. Have the child follow light or a bright toy through the six cardinal positions of gaze. | Eye |

| IV Trochlear† | Have the child move eyes downward and inward. | Eye |

| V Trigeminal* | Palpate the temple and jaw as the child bites down. Assess for symmetry and strength. Determine whether the child can detect light touch over the cheeks (a young infant roots when the cheek areas near the mouth are touched). Approaching from the side, touch the colored portion of the eye lightly with a wisp of cotton to test the blink and corneal reflexes. | Eye |

| VI Abducens† | Ask the child to look sideways. Assess the ability to move eyes laterally. | Eye |

| VII Facial* | Test the child’s ability to identify sweet (sugar), sour (lemon juice), or bitter (quinine) solutions with the anterior tongue. Assess motor function by asking the older child to smile, puff out the cheeks, or show the teeth. (Observe the infant while smiling and crying.) | Head and neck |

| VIII Acoustic | Test the child’s hearing (see Chapter 12). | Ear |

| Head and neck | ||

| IX | Test the child’s ability to identify the taste of solutions on the posterior tongue. | Head and neck |

| Glossopharyngeal† | ||

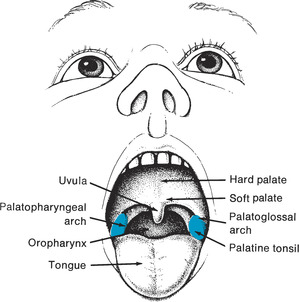

| X Vagus | Assess the child for hoarseness and ability to swallow. Touch a tongue blade to the posterior pharynx to determine if the gag reflex is present (cranial nerves IX and X both participate in this response). Do not stimulate the gag reflex if there is any suspicion of epiglottitis. Check that the uvula is in the midline. | Head and neck |

| XI Accessory† | Have the child attempt to turn the head to the side against resistance. Ask the child to shrug shoulders while downward pressure is applied. | Head and neck |

| XII Hypoglossal† | Ask the child to stick out the tongue. Inspect the tongue for midline deviation. (Observe the infant’s tongue for lateral deviation when crying and laughing.) Listen for the child’s ability to pronounce “r” (rabbit, run, Robert). Place a tongue blade against the side of child’s tongue and ask the child to move it away. Assess for strength. | Head and neck |

| Adapted from LeClare S et al: Recommendations for grading of concussion in athletes, Sports Med 31:629–636, 2001.(SOURCE) | |

| Grade | Assessments |

|---|---|

| Grade 1 | No loss of consciousness, no PTA |

| Grade 1A | No PCS seconds of confusion |

| Grade 1B | PCS and/or confusion (disorientation, inability to maintain coherent stream of thought or goal-directed movements, heightened distractibility) that resolves within 15 minutes |

| Grade 1C | PCS and/or confusion that lasts longer than 15 minutes |

| Grade 2 | PTA that lasts less than 30 minutes and/or loss of consciousness that lasts less than 5 minutes |

| Grade 3 | PTA that lasts longer than 30 minutes and/or loss of consciousness that lasts longer than 5 minutes |

Assessment of the cranial nerves varies with the child’s developmental and cognitive levels. Testing of several functions depends on the child’s ability to understand and cooperate; therefore, such functions cannot be tested in the infant or young child.

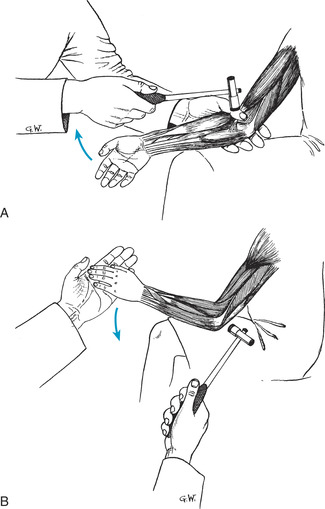

Assessment of Deep Tendon Reflexes

Assessment of deep tendon reflexes (Figure 21-2) provides information about the intactness of the reflex area. Compare the symmetry and strength of reflexes. Superficial reflexes such as the abdominal reflex, anal reflex, and cremasteric reflex can also be evaluated (Table 21-3) but are usually assessed during other areas of the health assessment. Findings from assessment of deep tendon and superficial reflexes are variable in infancy. Their absence or intensity is not diagnostically significant unless asymmetry is present.

|

| Figure 21-2Assessment of deep tendon reflexes. A, Biceps. B, Triceps.(From Whaley LF, Wong DL: Nursing care of infants and children, ed 4, St Louis, 1991, Mosby.)Elsevier Inc. |

| Reflex | Method of Assessment | Usual Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Deep Tendon Reflexes | ||

| Biceps | Partially flex the child’s forearm. Place your thumb over the antecubital space and strike with the reflex hammer (Figure 21-2, A). | Forearm flexes slightly |

| Triceps | Bend the child’s arm at the elbow while supporting the forearm. Strike the triceps tendon above the elbow (Figure 21-2, B). | Forearm extends slightly |

| Brachioradialis | Place the child’s arm and hand in a relaxed position with the palm down. Strike the radius 2.5 cm (1 in) above the wrist. | Forearm flexes and palm turns upward |

| Knee jerk or patellar | Have the child sit on a table or on the parent’s lap with legs flexed and dangling. Strike the patellar tendon just below the kneecap. | Lower leg extends |

| Achilles | Have the child sit on a table or on the parent’s lap with legs flexed, and support the foot lightly. Strike the Achilles tendon. | Foot plantar flexes (points downward); rapid, rhythmic plantar flexion of the foot can occur in newborn infants (as many as 10 flexions might be noted) |

| Superficial Reflexes | ||

| Abdominal | Stroke the skin toward the umbilicus. Assess the reflex in all four quadrants. The abdominal reflex might not be present for the first 6 months. (Can be incorporated into assessment of the abdomen.) | Umbilicus moves toward the stimulus |

| Cremasteric | Stroke the upper inner thigh. (Can be integrated into assessment of the abdominal or genital area.) | Testes retract into the inguinal canal |

| Anal | Stimulate the skin in the perianal area. (Can be incorporated into assessment of the rectal area.) | Brisk contraction of the anal sphincter occurs |

Infant reflexes or automatisms (Table 21-4) are particularly useful in assessing the function of the central nervous system. Reflexes should be formally assessed if there is any suggestion of a central nervous system disorder. Many reflexes can be assessed during other parts of the health assessment. Knowledge of the reflex aids in education of the parents.

| Reflex | Description | Method of Assessment | Significance of Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blinking (corneal or dazzle) | Closes eyelids in response to bright light. Present during first year of life. | Shine light into infant’s eyes. | Absence of reflex suggests blindness. |

| Babinski’s sign | Toes fan and big toe dorsiflexes. Disappears after 1 year. | Stroke sole of foot along outer edge, beginning from heel. | Fanning of toes and dorsiflexion of great toe after 2 years of age suggests lesion in extrapyramidal tract. |

| Crawling | Infant makes crawling movements with arms and legs when placed on abdomen. Disappears at about 6 weeks. | Place infant prone on flat surface. | Asymmetry of movements suggests neurologic disorder. |

| Dance or stepping | Infant’s feet move up and down when feet lightly touch firm surface. | Hold infant so that feet lightly touch firm surface. | Persistence of reflex beyond 4 to 8 weeks is abnormal. |

| Present for approximately first 4 weeks. | |||

| Extrusion | Tongue extends outward when touched. Present until 4 months of age. | Touch tongue with tip of tongue blade. | Persistent extension of tongue can indicate Down syndrome. |

| Galant’s (trunk incurvation) | Back moves toward side that is stimulated. Present for first 4 to 8 weeks. | Stroke infant’s back along side of spine from shoulder to buttocks. | Absence of reflex can indicate transverse spinal cord lesions. |

| Moro’s | Arms extend, fingers fan, head is thrown back, and legs might flex weakly. Arms return to center with hands clasped. Spine and lower extremities extend. Strongest during first 2 months. Disappears at 3 to 4 months. | Change infant’s position abruptly or jar table. | Persistence of reflex beyond 4 months suggests brain damage. |

| Persistence beyond 6 months highly indicates brain damage. | |||

| Asymmetry of responses indicates hemiparesis, fracture of clavicle, or injury to brachial plexus. | |||

| Absence of response in lower extremities indicates congenital hip dislocation or low spinal cord injury. | |||

| Neck righting | When infant is supine, shoulder and trunk and then pelvis turn toward direction in which infant is turned. Appears at 3 months and persists until 24 to 36 months. | Place infant supine. Attempt to attract infant’s attention to one side. | Absence or persistence beyond 10 months suggests central nervous system disorders. |

| Body righting | When infant is supine, all body parts follow when hips and shoulders are turned to one side. | Place infant supine. Turn hips and shoulders to side. | |

| Labyrinth righting | Infant able to raise head when prone or supine. Appears at 2 months and disappears by 10 months. | Place infant prone or supine. | |

| Parachute reflex | When infant is suspended horizontally and suddenly dipped downward, hands and fingers extend forward. Appears at 6 to 8 months and persists indefinitely. | Suspend infant and drop head and trunk. | |

| Palmar grasp | Infant’s fingers curve around finger placed in infant’s palm from ulnar side. Palmar grasp disappears by 3 to 4 months. | Place finger into infant’s palm from ulnar side. If reflex is weak or absent, offer infant bottle or soother because sucking enhances reflex. | Asymmetric flexion indicates paralysis. Persistence of grasp reflex indicates cerebral disorder. |

| Placing | Infant lifts leg off table as if stepping on to table. Time of disappearance variable. | Hold infant upright, under arms. Place dorsal side of foot briskly against table or other hard surface. | |

| Rooting | Infant turns in direction that cheek is stroked. Reflex disappears at 3 to 4 months but can persist until 12 months, especially during sleep. | Stroke corners of infant’s mouth or midline of lips. | Absence of reflex indicates severe neurologic disorder. Exaggerated rooting reflex together with ineffective sucking is associated with cocaine-dependent mothers. |

| Startle | Infant extends and flexes arms in response to loud noise. Hands remain clenched. Reflex disappears after 4 months of age unless there are neurologic impairments. Infants with neurologic impairments can evidence increased sensitivity to sound. | Claps hands loudly. | Absence of reflex indicates hearing impairment. |

| Sucking | Infant sucks strongly in response to stimulation. Reflex persists during infancy and can occur during sleep without stimulation. | Offer infant bottle or soother. | Weak or absent reflex suggests developmental delay or neurologic abnormality. |

| Tonic neck | Infant assumes fencing position when head is turned to one side. Arm and leg extend on side to which head is turned and flex on opposite side. | Turn head quickly to one side. | It is considered abnormal if response occurs each time head is turned. Persistence indicates major cerebral damage. |

| Normally reflex should not occur each time head is turned. Disappears at 3 to 4 months. |

Assessment of Pain

The response of children to pain follows developmental patterns (Table 21-5) and is influenced by temperament, coping abilities, and previous exposure to pain and painful procedures. When assessing pain, the use of various assessment strategies aids in obtaining a more accurate assessment of the pain. These strategies include questioning the child (in words that are appropriate to developmental level and language) and the parents, observing behavioral and physiologic responses, and using pain scales (Table 21-6). The Preverbal, Early Verbal Pediatric Pain Scale (PEPPS) (see the box on pp. 332-333) is a pain-measurement tool that is useful with toddlers and for taking and evaluating action. Headache is a common symptom in children and can indicate several disorders (Table 21-7).

| Age | Motor Response | Expressive Response | Ability to Anticipate Pain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Young infants | Generalized. Includes thrashing, rigidity, exaggerated reflex withdrawal, lack of sucking, disorganized sucking, starts to eat or drink and discontinues. | Cries loudly, closes eyes tightly, opens mouth in squarish manner, grimaces. | No link between approaching stimulus and pain. |

| Older infants | Localized. Withdrawal of affected area. Sucking and feeding behaviors as for young infants. | As for young infant except eyes can be open. | Physical resistance after painful stimulus occurs. |

| Young children | Thrashes arms, legs. Uncooperative, reluctant to move, lies rigid, guards area, restless. | Cries, screams loudly, moans, verbalizes pain, clings to support person, asks for support, irritable. | Anticipates pain. |

| School-age children | Includes behaviors found in young child, as well as muscular rigidity (clenched fists, body stiffness, closed eyes, frowning), muscle tension, and withdrawal. | Includes responses found in young child, as well as stalling or bargaining behavior. | Behaviors seen less before procedure; more pronounced during pain experience. |

| Adolescents | Less motor activity than for younger children. Demonstrates muscle tension, body control. | Uses more sophisticated language to verbalize pain. Less verbal protest. | Uses anticipation to prepare self. |

| FACES Pain Rating Scale from Hockenberry MJ et al: Wong’s nursing care of infants and children, ed 7, St Louis, 2003, Mosby.(SOURCE) | ||

| Tool | Instructions | |

|---|---|---|

| Adolescent pediatric pain tool (APPT) | Ask adolescent to color in areas of pain on anterior and posterior body outlines. Ask adolescent to make marks as big or as small as pain. | |

| Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale |

|

|

| Explain to the child that each face is for a person who feels happy because he has no pain (hurt) or sad because he has some or a lot of pain. Face 0 is very happy because he doesn’t hurt at all. Face 1 hurts just a little bit. Face 2 hurts a little more. Face 3 hurts even more. Face 4 hurts a whole lot. Face 5 hurts as much as you can imagine, although you don’t have to be crying to feel this bad. | ||

| Ask the child to choose the face that best describes how he or she is feeling. | ||

| Recommended for children age 3 and older. | ||

| Numeric scale | Ask the child to rate pain on a line from 0 to 10, with 0 being no pain and 10 being the worst possible pain. Useful for children who know how to count and who understand the concepts of more and less. | |

| Characteristics of Pain | Location | Factors that Aggravate or Provoke | Associated Symptoms | Possible Etiology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aching, mild, diffuse, tightness and pressure; gradual onset | Usually bilateral; can be generalized; can involve back of head and neck |

▪ School and relationship stressors

▪ Long periods in one position (e.g., working at a computer, playing video games)

|

▪ Depression

▪ Anxiety

|

Tension

headache

|

| Aching, progressive, recurrent; worse on arising | Occipital or frontal areas |

▪ Lowering head

▪ Bowel movements, coughing, sneezing

|

▪ Vomiting, with or without feeding

▪ Decreased appetite

▪ Increasingly projectile vomiting

▪ Clumsiness

▪ Changes in reflexia

▪ Spasticity

▪ Irritability

▪ Seizures

▪ Weakness

▪ Positive Babinski’s sign

|

Brain tumor |

| Aching, throbbing; variable severity; can be recurrent | Above eye (frontal sinus), in cheekbones, over gums (maxillary sinus) |

▪ Bending

▪ Coughing

▪ Sneezing

▪ Jarring the head

|

▪ Fever

▪ Nasal discharge

▪ Nasal congestion

▪ Halitosis

|

Sinusitis |

| Aching, steady, dull, in and around eyes | Around and over eyes | ▪ Activities requiring use of eyes such as reading, schoolwork, video games, television |

▪ Child might say eyes are tired

▪ Redness of conjunctiva

▪ Frequent rubbing of eyes

▪ Squinting

▪ Clumsiness

▪ Nausea following close work

▪ Closes one eye

|

Errors of refraction; strabismus |

| Steady, severe; abrupt onset, often after falling asleep; clustered over days or a week, with relief for weeks or months | One sided; high along the nose; over and behind the eye | ▪ Can be provoked by alcohol use |

▪ Coryza

▪ Reddening and tearing of the eye

|

Cluster

headaches

|

| Steady, aching; gradual onset following injury to head; more common in infancy than in older children | Variable location | ▪ Injury, sometimes forgotten because of passage of time |

▪ Alterations in levels of consciousness

▪ Irritability

▪ Difficulty feeding

▪ Excessive crying

▪ Weakness along one side

|

Subdural hematoma |

| Severe, worsening; interferes with sleep | Variable | ▪ Injury to the head, often to the parietotemporal region |

▪ Possible loss of consciousness at time of injury

▪ Drowsiness; difficult to arouse

▪ Confusion

▪ Difficulty with speaking

▪ Irritability, crying

▪ Unsteady gait (older child)

▪ Refusal of feeding

▪ Nausea

▪ Swelling in front of or above earlobe that increases in size

▪ Increased head circumference (infant)

▪ Pupil changes

▪ Papilledema (older child)

▪ Hemiparesis

|

Epidural hemorrhage |

| Steady, throbbing, severe | Generalized | ▪ Movement of the neck |

▪ Accompanies fever, chills, vomiting

▪ Irritability

▪ Agitation

▪ Vomiting

▪ Seizures

▪ Photophobia

▪ Poor feeding

▪ Resists flexion of neck

▪ Positive Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs

|

Meningitis |

| Throbbing, aching; variable severity; rapid onset | Usually frontal or temporal, but can be occipital; can start behind eye and radiate outward; can be one or both sides Can be localized |

▪ Alcohol

▪ Some foods (chocolate milk, cheese, soft drinks, food additives)

▪ Tension

▪ Premenstrual

▪ Noise, bright lights

|

▪ Nausea, vomiting

▪ Abdominal pain

▪ Visual disturbances

▪ Local weakness

▪ Sensory disturbances

|

Migraine |

| Variable quality and severity; following head injury |

▪ Mental and physical activity

▪ Excitement

▪ Bending

▪ Alcohol

▪ Noise, lights

|

▪ Can occur following injury to the head

▪ Poor concentration

▪ Irritability

▪ Restlessness

▪ Fatigue

|

Concussion |

Elsevier Inc.

Heart Rate

4—>40 beats/min above baseline

3—31-40 beats above baseline

2—21-30 beats above baseline

1—10-20 beats above baseline

0—baseline range

Facial

4—Severe grimace; brows lowered and tightly drawn together, eyes tightly closed

2—Grimace; brows drawn together, eyes partially closed, squinting

0—Relaxed facial expression

Cry (Audible/Visible)

4—Screaming

3—Sustained crying

2—Intermittent crying

1—Whimpering, groaning, fussiness

0—No cry

Consolability/State of Restfulness

4—Unable to console, restlessness, sustained movement

2—Able to console, distract with difficulty, intermittent restlessness, irritability

1—Distractable, easy to console, intermittent fussiness

0—Pleasant, well integrated

4—Sustained arching, flailing, thrashing, and/or kicking

3—Intermittent or sustained movement with or without periods of rigidity

2—Localization with extension or flexion or stiff and nonmoving

1—Clenched fists, curled toes, and/or reaching for or touching wound or area

0—Body at rest, relaxed positioning

Sociability

4—Absent eye contact, response to voice and/or touch

2—With effort, responds to voice and/or touch, makes eye contact, difficult to obtain and maintain

0—Responds to voice and/or touch, makes eye contact and/or smiles, easy to obtain and maintain; sleeping

Sucking/Feeding

2—Lack of sucking, refusing food or fluids

1—Disorganized sucking, attempting to eat or drink but discontinues

0—Sucking, drinking, and/or eating well

0—N/A; NPO and/or does not use oral stimuli

Total score:

Constipation: related to neurologic impairment, abdominal muscle weakness.

Impaired verbal communication: related to decrease in circulation in brain.

Diversional activity deficit: related to frequent lengthy treatment.

Self-care deficit: related to cognitive or neuromuscular impairment.

Altered role performance: related to physical illness.

Altered growth and development: related to physical disability.

Impaired physical mobility: related to sensoriperceptual impairments, neuromuscular impairments.

Altered family processes: related to transition, crisis.

Ineffective family coping, compromised: related to role disorganization, prolonged disease, situational crisis.

Impaired skin integrity: related to mechanical or chemical factors, impaired physical mobility.

Pain: related to injury agents.

Impaired social interaction: related to limited physical mobility.

Social isolation: related to alterations in mental status, altered state of wellness.

Altered thought processes: related to neurologic disturbance.

Impaired memory: related to neurologic disturbance, acute hypoxia.

Risk for disuse syndrome: related to paralysis.

Dysreflexia: related to bladder or bowel dysfunction, lack of caregiver knowledge, skin irritation.

Bowel incontinence: related to lower motor nerve damage.

Ineffective airway clearance: related to neuromuscular dysfunction.

Risk for injury: related to balancing difficulties, cognitive difficulties, reduced coordination, seizures.