CHAPTER 80 Nerve Entrapment Syndromes

INTRODUCTION

The diagnosis of a nerve entrapment lesion arising at the elbow can be relatively straightforward if the history, physical examination, electromyographic (EMG), and imaging studies, when indicated, all confirm the diagnosis and the localization of the lesion.12,32,47,87,93,138 However, when the history and physical examination do not correspond or the electrophysiologic or imaging studies do not support a specific clinical diagnosis, then problems can arise. Therefore, one must apply the same systematic, thoughtful approach to the care of every patient. One can then put all of the data of the clinical puzzle together to offer appropriate treatment.

Other issues may confound the clinical picture and the treating physician:

Recurrent neural compression lesions also occur. A physician may successfully care for an individual’s neural compression only for another nerve compression to arise a few months or years later that affects the same peripheral nerve or another nerve.132,139,198 Usually, technical factors at surgery can prevent recurrent lesions. Free gliding of the nerve with elbow flexion and extension and forearm rotation helps prevent late postoperative symptoms. If a nerve is fixed by adhesions or scarring or at a fracture site, it is not just a matter of entrapment. A traction neuritis can exist as well. As the joint moves, the nerve is tethered and can be stretched. If the ulnar nerve is transposed anteriorly (especially if it has not been transposed in a straight line), ulnar neuritis can develop at a later date. Similarly, if the medial epicondyle is resected and the nerve becomes adherent to the medial epicondylectomy site, resistant ulnar nerve neuritis can develop after the primary surgery.

A detailed understanding of the complex normal anatomy of this region and the “common” variants is essential for proper diagnosis and treatment of these conditions (Fig. 80-1). Careful history, serial examinations and EMG studies, and at times, imaging modalities can usually localize the lesion or lesions. Early, accurate diagnosis and treatment are important for effective overall management of nerve compression lesions. Understanding the degree of nerve injury can help a physician predict recovery patterns and guide management.

NEUROPHYSIOLOGY OF NERVE COMPRESSION LESIONS

Nerve compression may be categorized as first-, second-, third-, or fourth-degree neural lesions. This method was first described by Sir Sydney Sunderland.184 The earlier classification of Sir Herbert Seddon (1943)157 uses the terms neurapraxia, axonotmesis, and neurotmesis and can be correlated with Sunderland’s classification in the following manner. A first-degree lesion is a neurapractic lesion. A second-degree or mild third-degree lesion is an axonotmetic lesion. The neurotmetic lesion encompasses all of the fourth-degree lesions (the neuroma in continuity) and the advanced third-degree lesions. I prefer using Sunderland’s classification when correlating clinical problems with the underlying nerve fiber pathologic condition present (Table 80-1).139

TABLE 80-1 Correlation of Seddon and Sunderland Classification of Nerve Injuries*

|

*Shaded areas indicate equivalent terms.

With neural compression lesions, it is rare to have a pure first-, second-, or third-degree lesion. Most often, these lesions are mixed. One of the degrees of injury usually predominates in a particular case.138 The lesion mix can be determined by serial physical examinations, preoperative and postoperative serial EMG studies, and knowledge of the duration of the partial or complete nerve compression lesions. A fourth-degree nerve compression lesion is found most often when motor and sensory complete paralysis of a particular nerve has existed for more than 18 months.

The factors that affect return of nerve function following entrapment lesions are (1) the nerve fiber pathology, (2) the duration of the lesion and whether it is complete or partial, (3) the status of the end organs (i.e., motor and sensory), and (4) the level of the lesion.120 When a nerve is entrapped, it is the peripheral fibers that are the most vulnerable to the pathologic process. Similarly, the heavy myelinated fibers are more susceptible to compressive forces.

There appear to be several types of first-degree injury. These lesions are correlated best when both the nerve fiber pathologic processes and the clinical recovery following neurolysis are analyzed temporally. There are ionic96 and vascular40,109,117 lesions of nerve fibers that respond to release by prompt recovery within, at times, hours of surgery. There is a structural first-degree lesion, described by Gilliatt and colleagues64 and Ochoa,136 in which there is segmental injury to the nerve fiber consisting of segmental demyelination and remyelinization of just a few nodal segments of the fibers. In this instance, the entire recovery process takes 30 to 60 days. The clinical implications of this particular lesion are as follows: whether the lesion is high or low in the nerve, it takes 30 to 60 days for neural function to be restored.

RADIAL NERVE

The radial nerve and its major branches, the posterior interosseous nerve and the superficial radial nerve, are vulnerable to compression forces from the level of the lateral head of the triceps through the region of the elbow, proximal forearm, and even into the distal forearm.27,53,133 Depending on which branch of the nerve is involved at the elbow, either pure motor (posterior interosseous nerve) or sensory (superficial radial nerve) paralysis can occur; rarely, motor and sensory involvement can be due to a process in the proximal forearm affecting both branches rather than the radial nerve itself.

Relevant Anatomy

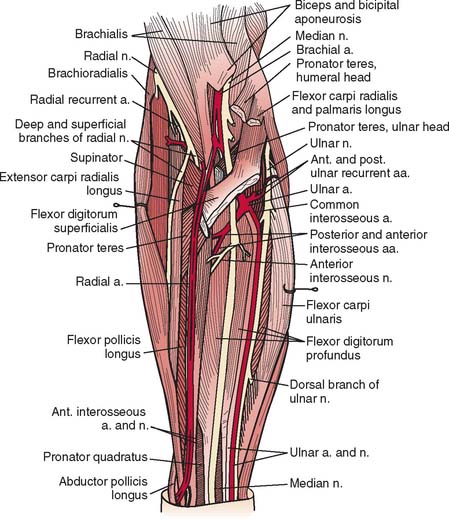

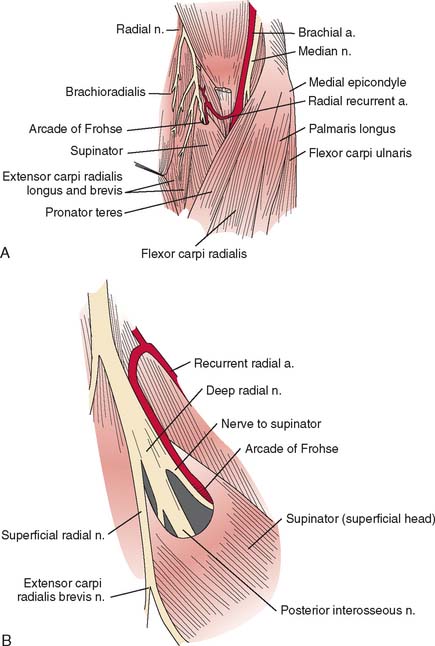

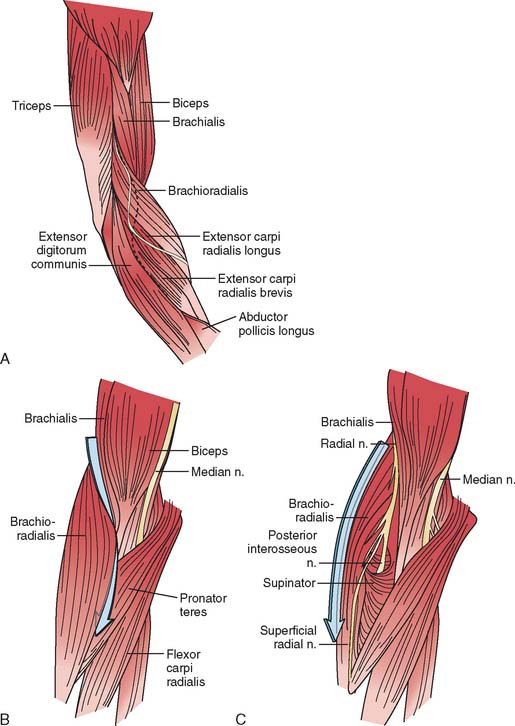

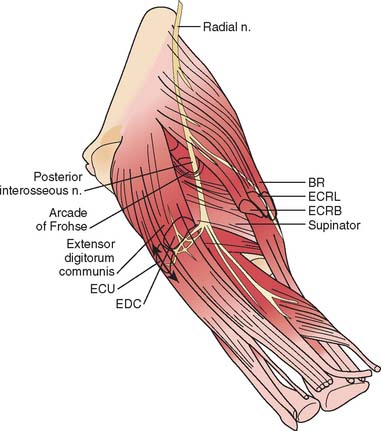

The radial nerve in the distal arm passes anteriorly, 10 cm proximal to the lateral epicondyle (Fig. 80-2).80 At the level of the radiocapitellar joint, it divides into its major branches, the deep and the superficial radial nerves. In this passage, the radial nerve passes just deep to the fascia of the brachioradialis. Above the elbow, the radial nerve innervates the brachioradialis and the extensor carpi radialis longus. The motor branch to the extensor carpi radialis brevis arises from the superficial radial nerve in 58% of the population.155 It frequently arises as a separate terminal branch of the radial nerve with the posterior interosseous and superficial radial nerves.

At the elbow, the deep branch passes between the two heads of the supinator muscle, where it becomes the posterior interosseous nerve.31 The proximal edge of the supinator forms an arch for the posterior interosseous nerve, the arcade of Frohse. The superficial radial nerve passes superficial to the supinator muscle. It is covered anteriorly by the brachioradialis. Recurrent vessels of the radial artery cross superficial and deep to these radial nerve branches. The posterior interosseous nerve courses in a dorsoradial direction in the proximal forearm. As it passes through the supinator, it innervates this muscle by multiple branches. Approximately 6 to 8 cm below the elbow joint, this nerve emerges from the supinator muscle, where it divides into its terminal motor branches to the extensor digitorum communis, extensor digiti minimi, extensor carpi ulnaris, abductor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis longus and brevis, and extensor indicis proprius.

Posterior Interosseous Nerve Syndrome

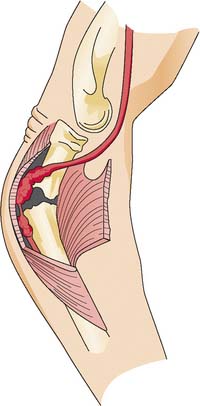

The deep branch can be compressed by a fibrous band or thickened proliferating rheumatoid synovium from the radiocapitellar joint,18,114,116 the radial recurrent artery, or the leading tendinous edge of the extensor carpi radialis brevis.119 Next, the posterior interos-seous nerve can be compressed at the arcade of Frohse,54,118,134,152,163,168,196 the most common site of compression. It may also be compressed by fibrotic bands within the midportion of the supinator26 and its distal end. Other causes of compression include adhesions at the anterior aspect of the distal humerus, muscular anomalies, vascular aberrations,41 bursae,2 inflammatory thickening, and adherence of the extensor carpi radialis brevis119 tendinous origin to the proximal edge of the supinator on its radial side.19,20 Some have identified focal constriction within the posterior interosseous nerve.71,94 Posterior interosseous nerve palsy may result from fractures124,179 or fracture-dislocations (Fig. 80-3).122,171 Tardy posterior interosseous nerve palsy may also occur years after unreduced Monteggia fracture-dislocations73,105 or after radial osteomyelitis (Fig. 80-4).176 Tumors may compress the nerve primarily, which can be secondarily compressed by a structure such as the arcade of Frohse.7,11,17,151,178,200

Classically, the clinical presentation of this nerve paralysis is thought to be typically motor because the posterior interosseous nerve basically carries motor fibers destined to innervate the extensor digitorum communis, extensor digiti minimi, extensor carpi ulnaris, abductor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis longus and brevis, and extensor indicis proprius. However, pain simulating lateral epicondylitis is also recognized as a common early presentation (see later discussion).19 Because of the segmental innervation of the supinator, the proximal or distal location of the compression of this nerve in the supinator can be determined by evaluating the electromyogram occasionally. Fibrillations in the supinator muscle suggest that the compression is proximal, at the arcade of Frohse. The pattern of involvement of this nerve varies depending on whether the entire nerve is compressed or whether there is a partial paralysis. When the entire posterior interosseous nerve is compressed, the fingers and thumb cannot extend at the metacarpophalangeal level and the wrist deviates in a radial direction with wrist extension (because the branches to the extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis usually take off more proximally) (Fig. 80-5).15,197 An untreated partial paralysis commonly evolves into a complete paralysis. Wristdrop signifies a lesion proximal to the posterior interosseous nerve branch (Fig. 80-6).

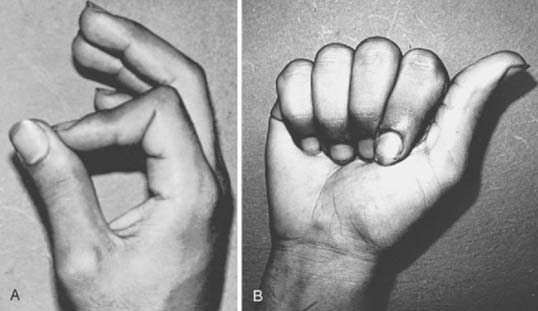

With partial paralysis, some of the digits, for example the fourth and fifth fingers at the metacarpophalangeal joints, do not extend but the others do.41,66,78,126 This attitude looks like a “pseudoulnar” claw hand. In reality, there is no clawing but only a drop at the metacarpophalangeal joint and no true hyperextension of the metacarpophalangeal joints of the fourth and fifth fingers, as is present in a typical ulnar nerve palsy (Fig. 80-7).

Understanding the branching pattern of the posterior interosseous nerve can assist in further localization of partial lesions. Different patterns of presentation have been described and localized.72,77,173,181 These include dropped finger (all) and thumb deformity; dropped long-ring, and little finger (and extensor carpi ulnaris) deformity; dropped thumb (abductor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis brevis and longus, and extensor indicis proprius) deformity; and dropped long and ring fingers only (“sign of the horns”). If surgery is entertained for incomplete lesions, the exit of the supinator should also be explored. In both partial and complete posterior interosseous nerve paralysis, sensation in the autonomous region on the dorsum of the first web space of the hand is uninvolved.

On occasion, isolated superficial radial nerve entrapment may occur in the elbow or proximal forearm region, but it is more commonly involved in the distal forearm or wrist. Isolated radial sensory paresthesias are usually secondary to irritations to the nerve in the region of the radial styloid. A compression neuropathy may occur in which this nerve penetrates the deep fascia in the midforearm between the brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis longus.37 Focal tenderness usually identifies the involved site.

Plain radiographs may be helpful in showing a fat stripe of a lipoma or a bony lesion in the vicinity of the radial neck (see Fig. 80-4). Ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may demonstrate an occult ganglion or elucidate a palpable mass by its imaging characteristics (Fig. 80-8).178 MRI is helpful in demonstrating denervation atrophy and hyperintensity in the nerve, which may help confirm a diagnosis or localization of nerve compression, or both. Electrical studiestypically demonstrate denervational changes in the muscles innervated by the posterior interosseous nerve. If there are no EMG abnormalities in the supinator, then one should have a suspicion that the compression lesion of the posterior interosseous nerve is at the distal end of this muscle rather than at its proximal end. The brachioradialis and the extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis should not reveal any abnormalities in the typical posterior interosseous nerve syndrome because these muscles are innervated by the radial nerve proximal to the arcade of Frohse. Because of the overlap of posterior interosseous nerve syndrome with many cases of Parsonage-Turner syndrome, EMG should examine other muscles (e.g., shoulder muscles) to identify a more diffuse neurologic process that would favor the diagnosis of an inflammatory disease. The favorable response of operative decompression in some patients with posterior interosseous nerve “entrapment” may well be due to a favorable natural history of Parsonage-Turner syndrome. I believe that Parsonage-Turner syndrome is underrecognized. For this reason, I recommend performing decompression after 6 months of observation in patients with spontaneous onset of symptoms in whom mass lesions are not discovered and there has not been any clinical recovery.

Resistant Tennis Elbow (Radial Tunnel Syndrome)

For the most part, resistant tennis elbow is caused by degeneration or fascial tears at the lateral epicondyle. On occasion, persistent complaints have been attributed to either compression of the posterior interosseous nerve or to a combination of nerve compression and persistent localized epicondylitis.20,153,165 Resistant pain localized to the proximal forearm should suggest that entrapment of the adjacent posterior interosseous nerve may be an unrecognized factor.

EMG studies in cases of resistant tennis elbow due to entrapment of the posterior interosseous nerve are often normal, even if the condition has been present for months and with definite clinical findings. Conduction delays are observed rarely. Stress testing as described by Werner193 has sometimes been helpful in confirming the diagnosis. Fibrillations in the muscles innervated by the posterior interosseous nerve are usually sparse, but if present, they are most likely in the extensor indicis proprius. If fibrillations are widespread in the more severe lesions, weakness of the finger extensors and extensor carpi ulnaris is also usually evident.

Patients suspected of having coexisting lateral epicondylitis and posterior interosseous nerve compression, who fail conservative treatment, should have both conditions treated simultaneously. Patients with persistent pain after surgery for lateral epicondylitis should be suspected of having posterior interosseous nerve compression.121

Preferred Operative Exposure for the Entire Course of the Posterior Interosseous Nerve

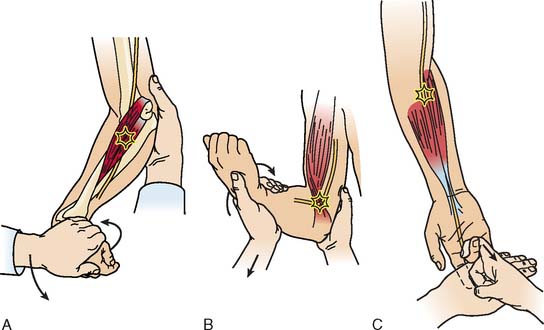

When exposure of the entire posterior interosseous nerve is needed, the plane between the extensor carpi radialis brevis and the extensor digitorum communis (Fig. 80-9) is developed. The incision begins 5 cm proximal to the lateral epicondyle and passes over the lateral epicondyle down to the region of the origin of the outcropping muscles (abductor pollicis longus, extensors pollicis longus and brevis). The aponeurotic plane between the extensor carpi radialis brevis and the extensor digitorum communis is developed from distal to proximal (Fig. 80-10). Identification of the plane is facilitated by passive motion of the fingers while the wrist is held steady, and the plane can be developed by blunt dissection. The supinator muscle is seen in the depth of the wound as these muscles are liberated. To gain complete exposure to the proximal end of the supinator, the extensor carpi radialis brevis tendon can be detached from its origin at the lateral epicondyle. At times, the distal portion of the origin of the extensor carpi radialis longus is detached, if necessary, for complete exposure of the underlying arcade of Frohse. This is facilitated with elbow flexion. Adherence of the tendinous origin of this muscle to the lateral portion of the supinator muscle is frequently found and is freed to give exposure to the proximal end of the supinator. One can identify the posterior interosseous nerve by flexing the elbow and by palpating the nerve’s course as it passes obliquely through the supinator in a dorsoradial direction. By gently spreading longitudinally through the fat on both sides of the nerve with a right-angled hemostat, the nerve can be isolated. Because there are recurrent vessels in the vicinity, dissection must be gentle. Any vessels crossing the nerve should be clamped and tied individually. When the posterior interosseous nerve is identified proximal to the arcade of Frohse, a vasoloop is passed about it so that its identity and continuity are maintained. The arcade of Frohse may be found to be thickened. A hemostat is placed deep to the arcade but superficial to the nerve, and the arcade is incised, liberating the most proximal portion of the nerve. If further surgery is necessary, the entire posterior interosseous nerve can be traced and brought into direct view. Compression of the proximal and distal region has been described, as well as compression of the nerve in its midportion.177 Epineurotomy of the posterior interosseous nerve at the site of its compression on occasion may be deemed necessary. Microsurgical technique should be used when this is indicated.

The detailed anatomy of the nerve supply to the extensor digitorum communis is important because this muscle obtains its innervation from branches of the terminal portion of the posterior interosseous nerve that run at right angles to the plane of the forearm in the distal portion of the proximal third of the forearm (see Fig. 80-10).173 The operating surgeon should not sweep the planes between the extensor digitorum communis and the supinator because these branches are vulnerable. Furthermore, strong retraction posteriorly of the extensor digitorum communis in this area could damage the nerve supply to this important muscle.

If a limited approach to the proximal portion of the supinator is needed, I prefer an anterior exposure of the posterior interosseous nerve. The lesion localized to the arcade of Frohse is approached by developing the plane proximal to the elbow between the brachialis and brachioradialis (see Fig. 80-9). Distal to the elbow, the anatomic dissection is continued, and the plane between the brachioradialis and the pronator teres is developed. If the dissection is difficult because of scarring or muscle anomalies, the superficial radial nerve can be identified distally and traced proximally to the main radial nerve and then to the deep branch. Any obstructing collateral vessels are ligated. The proximal third of the posterior interosseous nerve can be best visualized with this exposure. If necessary, the rest of the nerve can be followed by a separate posterior approach.

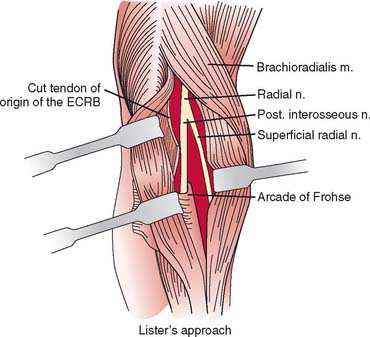

A longitudinal transmuscular approach through the brachioradialis has been popularized by Lister and associates.107 It provides direct access to the nerve from the radiohumeral level to the midsupinator (Fig. 80-11).

ULNAR NERVE

Relevant Anatomy

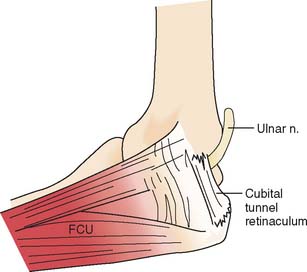

At the elbow, the ulnar nerve90 passes posterior to the medial epicondyle through the cubital tunnel. The cubital tunnel retinaculum137 (Fig. 80-12) seems to be the predominant site of pathology for patients with primary symptoms. In the proximal arm, the nerve descends in the anterior compartment. In the majority of upper extremities, the ulnar nerve crosses from the anterior to the posterior compartment in the distal arm. The anatomy of the region (about 8 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle), corresponding to the so-called arcade of Struthers, is controversial.164 The ulnar nerve, similarly, passes from posterior to the medial epicondyle to the anterior compartment of the forearm a few centimeters distal to the medial epicondyle and the cubital tunnel.

In the arm, there usually are no branches of the ulnar nerve of significance. Occasionally there is a variant high take-off of a motor branch to the flexor carpi ulnaris in the distal arm. The dorsal cutaneous nerve of the forearm, the sensory branch to the dorsoulnar aspect of the hand, rarely has been observed to arise in the proximal rather than the distal forearm. At the elbow level, the first branch is usually an expendable articular branch that arises just distal to the medial epicondyle; next are usually varying branches of the flexor carpi ulnaris and the motor branch to the fourth and fifth flexor digitorum profundus muscles. Stimulation of these branches can help the physician in deciphering whether the branch is a motor branch to an end organ or an articular branch. In addition, fascicular mobilization of these branches can be performed safely for a distance up to 6 cm to facilitate ulnar nerve transposition.192

Etiology

Ulnar nerve compression lesions may be due to many factors.4,69,110,140,141,189,190 At the elbow level, spontaneous compression neuritis is well known as the cubital tunnel syndrome.49 It is second only to carpal tunnel syndrome in its frequency.

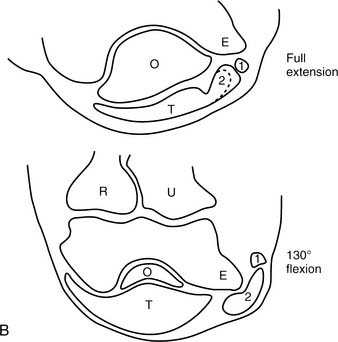

Ulnar nerve lesions may be due to compression, stretch, traction, friction, or a combination of these. Direct pressure on the posterior aspect of the elbow can compress the nerve and is seen in patients following coma, in surgical cases, or even in those who use wheelchairs. Flexion of the elbow may exacerbate symptoms, because it causes tightening and narrowing of the cubital tunnel and traction-related deformation of the nerve.60 The tendinous origin of the flexor carpi ulnaris can compress this nerve between its ulnar and humeral heads with elbow flexion.6 Extrinsic pressure on the nerve may result from the anconeus epitrochlearis,29,102 a variant muscle crossing the ulnar nerve in the region of the medial epicondyle, or from adhesions. Tumors130 such as ganglia14,89 may also be a causative factor.

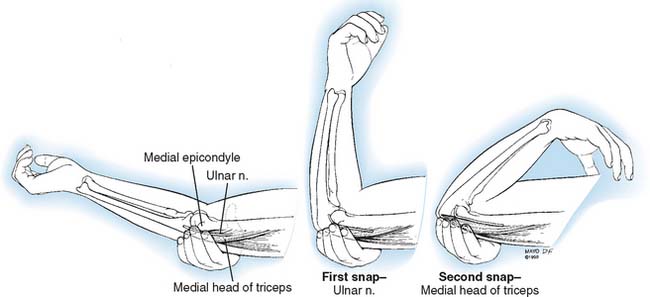

A hypermobile ulnar nerve can produce symptoms.23 This usually occurs during elbow flexion, as the nerve dislocates from the undersurface of the medial epicondyle to a position anterior to the epicondyle. Snapping of the medial triceps43,75,149,154,175 may be found in association with a dislocating ulnar nerve, and this can result in elbow pain, snapping, and ulnar nerve symptoms (Figs. 80-13 and 80-14). Persistent pain after an otherwise successful ulnar nerve transposition may represent unrecognized snapping of the triceps.

Bony changes at the elbow, whether acute or chronic, can result in ulnar nerve symptoms. Fracture-dislocations, medial epicondylar fractures, arthritic changes from osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis,45,104 callus, heterotopic bone, and spurs have been implicated. Both cubitus valgus and varus deformities1,56,188 may produce late ulnar nerve symptoms at the elbow.

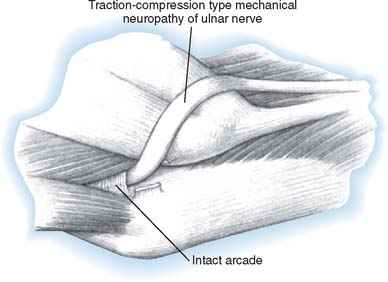

Iatrogenic causes of secondary ulnar nerve compression are numerous and related to technical factors.57 Compression may occur when the ulnar nerve is transposed anteriorly and is insufficiently mobilized, proximally or distally.169,170 After a previous transposition, secondary compression can be found proximally at the level of the so-called arcade of Struthers or distally where the ulnar nerve passes in the region of the common aponeurosis for the humeral head of the flexor carpi ulnaris and the origin of the flexor digitorum superficialis.86 If these aponeurotic areas are not released sufficiently both proximally and distally (Fig. 80-15), then potential secondary sites of entrapment are created, which can produce symptoms.172 The medial intermuscular septum should be excised because it, too, is a common cause of secondary ulnar nerve entrapment. However and whenever, the ulnar nerve is transposed, it should be transposed anteriorly without kinking. Tight slings used to maintain the nerve in an anterior position may result in secondary compression.103,108 Furthermore, traction neuritis can result when the nerve is transposed into a groove in the flexor-pronator group of muscles. When the nerve heals in the muscular groove, the longitudinal fibrotic aponeuroses of flexor muscles of the medial aspect of the elbow can produce secondary traction neuritis.

Clinical Presentation

A patient with an ulnar nerve lesion at the elbow typically presents with a combination of elbow pain and sensory and motor complaints. It usually begins with intermittent paresthesias in the ring and little fingers that are aggravated by elbow flexion and frequently awaken the patient. Sensory loss in the ring and little fingers of the hand usually occurs later, but sensory loss in the dorsoulnar aspect of the hand is a classic localizing sign. Usually, there are no sensory abnormalities in the forearm. The sensory fibers and the intrinsic motor fibers lie more peripherally than the fibers of the flexor digitorum profundus or the flexor carpi ulnaris and may explain their vulnerability early on. Motor weakness may be progressive in both the extrinsics and the intrinsics; at times, significant motor findings can be present with minimal sensory symptoms. With paralysis of the flexor digitorum profundus to the ring and little fingers, there is usually minimal clawing or no clawing of the ring and little fingers. With partial lesions, clawing may be more pronounced if the flexor digitorum profundus muscles are intact and the intrinsic muscles are atrophic.113,182 However, if the metacarpophalangeal joints of the ring and little fingers cannot hyperextend because of innate tightness of the volar plates, then clawing will also not be observed.

A mechanical lesion of the ulnar nerve at the elbow may present with different clinical patterns in different patients because of the presence or absence of neural anomalies and the extent of involvement of the nerve. There are numerous variations in fibers carried within the ulnar nerve at the elbow level.169 In 15% of upper extremities, the median nerve will carry many of the intrinsic motor fibers to pass from the median nerve or the anterior interosseous nerve branch of the median nerve to the ulnar nerve in the midforearm.

The sensory pattern typical of an ulnar nerve lesion at the elbow with diminished or absent sensation on the dorsoulnar aspect of the hand100 may not be observed. This may occur when other sensory nerves take over the area usually supplied by the dorsal cutaneous branch of the forearm. One variant sensory pattern is observed when the superficial radial nerve not only innervates the dorsal radial aspect of the hand but also extends to supply the dorsoulnar aspect. Furthermore, sensation in all of the ring and middle fingers can be affected in some complete ulnar nerve lesions.

Differential Diagnosis

In the differential diagnosis, a nerve lesion that involves the cervical foramina, as in cervical arthritis, can present with ulnar nerve type symptoms. Restriction and pain on movement of the neck, positive foraminal compression maneuvers, arthritic changes seen radiographically, and cervical paravertebral muscle electrical abnormalities are usually noted. Short segment stimulation may be effective in isolating the level of the compression to the ulnar nerve at the elbow.46

Entrapment in the hand is much less common than entrapment at the elbow; entrapment in the forearm is even rarer. Depending on the level of nerve involvement, varying clinical signs and symptoms become manifest. In a full-blown lesion in Guyon’s canal, there is usually more significant (“paradoxical”) clawing of these digits because the flexor digitorum profundus is functioning (see Fig. 80-7). The sensation on the dorsoulnar aspect of the hand is intact, whereas the palmar aspect of the hand may have some hypesthesia. Lesions of the ulnar nerve in the proximal forearm have findings similar to those at the elbow, whereas in the middle and distal forearm, symptoms depend on the relationship of the lesion to the motor branch of the flexor digitorum profundus and the dorsal cutaneous branch of the forearm. A lesion distal to the take-off of the motor branch of the flexor digitorum profundus is usually seen in patients with clawing. A lesion proximal to the dorsal cutaneous branch presents with numbness in the dorsoulnar aspect of the hand.

Operative Treatment

There are several different approaches for the surgical intervention of the ulnar nerve: simple decompression, medial epicondylectomy, subcutaneous, intramuscular and submuscular transposition and endoscopic or arthroscopic techniques. Many surgeons over the years have passionately advocated a particular technique under all circumstances, whereas others have suggested that the choice of operative procedure52 should be fitted to the patient’s symptoms and the EMG findings. Despite these opinions, recent prospective studies performed in primary cases have not demonstrated any statistical differences between simple decompression and the different types of anterior transposition.8,10,61,128,202 As a result, simple decompression in these cases is becoming more commonly performed. In secondary cases, submuscular transposition is the procedure of choice.

For mild and moderate ulnar nerve compression, I perform a simple release of the cubital tunnel.24 If the nerve is noted to dislocate intraoperatively after release, I perform an anterior subcutaneous translocation, the same procedure that I perform currently in most patients with severe ulnar neuropathy. If the patient has no fat in the subcutaneous tissue, or in revision surgery, I prefer the Learmonth procedure, the submuscular anterior translocation of the ulnar nerve.101,103 I do not perform submuscular transposition in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or in those with post-traumatic medial bony changes.

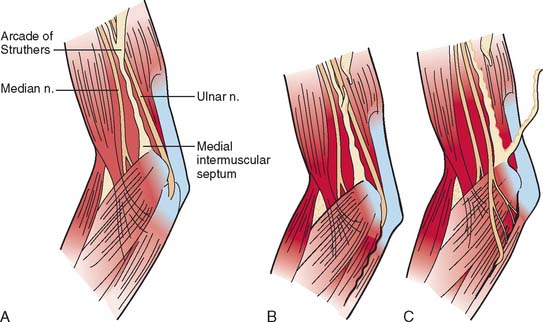

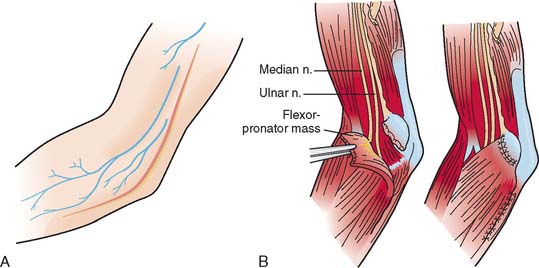

Preferred Operative Exposure for Anterior Transposition of the Ulnar Nerve

The incision extends 5 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle and 4 cm distal to the medial epicondyle on the posteromedial side of the elbow (Fig. 80-16A). The V-shaped flap formed at the elbow level is undermined subcutaneously and is retracted medially. The medial cutaneous nerves of the forearm and arm are identified and preserved by vasoloops about them. Avoidance of injury to them is important because patients afflicted with ulnar entrapment lesions are vulnerable to symptomatic postoperative skin neuromata.38 The plane between the subcutaneous fat and the brachial and antebrachial fascia in the distal arm is delineated and undermined. The medial intermuscular septum is seen, and the ulnar nerve is identified just posterior to the medial intermusclar septum in the distal third of the arm. In approximately 70% of limbs, muscular fibers of the medial head of the triceps have been reported to cross the ulnar nerve and attach to the so-called arcade of Struthers, 8 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle. If these muscular fibers of the medial head of the triceps are noted, it is a clear indication that the ulnar nerve must be liberated in this area (see Fig. 80-16B). The medial intermuscular septum is cleared posteriorly of muscular fibers to the level of the humerus. Anteriorly, the medial intermuscular septum is separated with care from the neurovascular bundle. The inferior ulnar collateral vessels, which penetrate the intermuscular septum, can be preserved, and the medial intermuscular septum is excised (see Fig. 80-16C). The ulnar nerve is mobilized. Its external longitudinal vessels are kept in continuity with the nerve. The transverse components of the vascular supply can be cauterized, preferably with a bipolar unit, keeping the external and internal vascular supply intact. At the level of the posterior aspect of the medial epicondyle, the ulnar nerve is liberated and an articular branch to the adjoined surface is sacrificed. One or two rubber bands are placed about the ulnar nerve to aid in the dissection. Distal to the medial epicondyle, the ulnar nerve is identified as it passes through the cubital tunnel. The tendinous arch for the origin of the flexor carpi ulnaris of the humerus and ulna in the proximal region is identified. The humeral attachment is detached, and the interval between the common aponeurosis of the flexor carpi ulnaris humeral head and the flexor digitorum superficialis is defined. The ulnar nerve is identified distally, deep to the flexor carpi ulnaris. Its common fibrous aponeurosis is liberated to free the ulnar nerve in the proximal forearm. The multiple branches of the flexor carpi ulnaris are preserved. The motor branch to the flexor digitorum profundus of the ring and little fingers is also identified and preserved. The ulnar nerve is mobilized in the proximal third of the forearm with the use of loupe magnification and microsurgical technique to permit nontethered anterior translocation.67 At this point, the nerve can be placed in a subcutaneous plane or placed in a submuscular position. A loose fasciodermal sling44 or the medial intermuscular septum145 may be used to stabilize the ulnar nerve; before wound closure, the elbow should be passively flexed and extended to ensure that ulnar nerve compression has been eliminated and to check that snapping of the medial portion of the triceps is not present.175 If snapping of the medial triceps is identified either preoperatively or intraoperatively, one can transpose laterally or excise the offending dislocating portion of the medial triceps.

To proceed with the Learmonth procedure, the median nerve is identified proximal to the lacertus fibrosus in the distal arm and a rubber band is placed around it (Fig. 80-17). The median nerve is found deep to the brachial fascia at the elbow level medial to the brachial artery. The lacertus fibrosus in the proximal forearm is incised longitudinally. The next step in the dissection is to detach the muscles of the flexor-pronator group 1 cm distal to the medial epicondyle. To accomplish this, a tonsillar clamp is placed from the radial side of the flexor-pronator group of muscles 1 cm distal to the medial epicondyle and passed medially deep to the flexor-pronator group of muscles to exit in the region of the cubital tunnel. The tonsillar clamp is passed superficial to the ulnar collateral vessels on the anterior aspect of the medial side of the forearm. The flexor-pronator origin is incised sharply. The brachial fascia is identified. By a combination of sharp dissection and periosteal stripping, the flexor-pronator group of muscles is stripped distally. The tourniquet is released. Any additional bleeding is brought under control either by ties or with the bipolar electrocautery. The ulnar nerve is translocated anteriorly adjacent to the median nerve, and the flexor-pronator origin is repaired (Fig. 80-17B). Z-lengthening or advancement of the flexor-pronator origin can also be performed.33–35135 The subcutaneous tissues and skin are closed with either interrupted or subcuticular sutures. After a submuscular transposition, the elbow is immobilized in a semiflexed position with the forearm in midposition and the wrist in neutral; the fingers and thumb are free. The immobilization is continued for 7 days followed by progressive active extension in a blocking splint.

I do not have direct experience with medial epicondylectomy28,55,63,84,85,158 and do not like intramuscular transposition for ulnar nerve neuritis, although other surgeons have reported success with these techniques. Endoscopic and arthroscopic techniques are being employed by some surgeons.79,95,144,187

MEDIAN NERVE

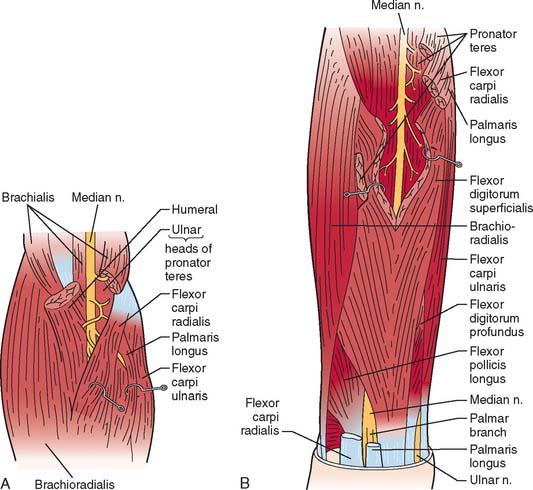

Relevant Anatomy

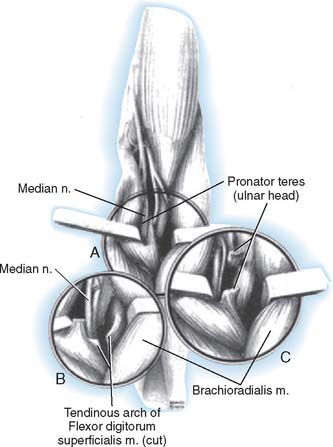

The median nerve lies beneath the brachial fascia on the medial aspect of the arm resting on the brachialis muscle (Fig. 80-18).80 The brachial artery and veins lie laterally in close proximity and adjacent to the biceps tendon. The medial intermuscular septum lies posteriorly and attaches to the medial epicondylar flare. The median nerve passes first alongside the humeral origin of the pronator teres and then beneath it to lie on the deep surface. It most often passes between the humeral head and the ulnar head of the pronator muscle but may pass deep to both heads, or the ulnar head may be absent. Fibrous arches may play a role in the nerve compression.39 The motor branches of the pronator teres usually arise from the medial aspect of the nerve beneath the upper margin of the muscle but variably arise above the antecubital area. The branch to the ulnar head may arise from the main branch or as a separate branch from the median nerve. The anterior interosseous branch arises deep and usually laterally at the level of the deep head of the pronator teres and in close approximation to the bifurcation of the radial and ulnar arteries from the brachial artery.68,81 The main branch of the median nerve next passes beneath the tendinous arch of origin of the flexor digitorum superficialis and lies in close approximation to the deep surface of this muscle (see Fig. 80-18B). The anterior interosseous nerve runs onto the index flexor digitorum profundus muscle and the flexor pollicis longus.112

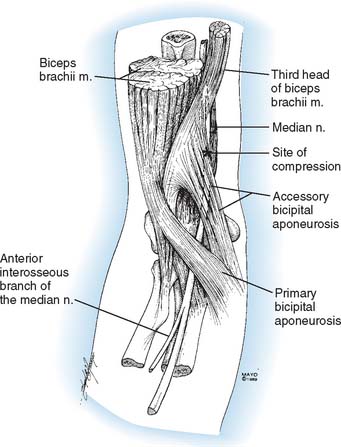

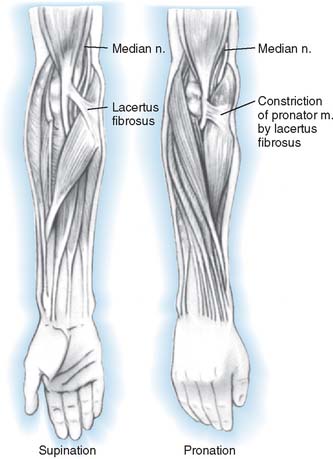

Altered anatomy, whether from anatomic variation or a pathologic condition, may play an important part in causing nerve compression syndromes.51,98 The most important for median nerve compression about the elbow are the supracondylar process and ligament of Struthers,180 the Gantzer muscle,3,59 the palmaris profundus,169 the flexor carpi radialis brevis,169 a variant lacertus fibrosus (Fig. 80-19),174 and vascular perforation or tethering of the nerve.13 Distal humeral fracture or dislocation is well known to cause median nerve injury.106,146

Supracondylar Process

Compression of the median nerve at the level of the distal humerus may occur when the nerve passes beneath the osseous process,115 which extends obliquely midanteriorly and continues to the medial epicondyle as the ligament of Struthers.62 (Ulnar nerve compression may rarely occur in association with a supracondylar process and the ligament of Struthers.) Muscle hypertrophy or strenuous use may facilitate the irritant effect of this structure.80 The supracondylar process has been a compressive factor in approximately 40 case reports. The supracondylar spur may be associated with proximal extension of the humeral head of the pronator teres, which may also be a factor in compression of the median nerve.

Pronator Syndromes

The pronator syndrome has been described as a neural compression syndrome within the proximal forearm.70,82,83,92,123,161,194 It is a controversial disorder. The symptoms are often vague, consisting of discomfort in the forearm with occasional proximal radiation into the arm. A fatigue-like pain description may be elicited. Numbness of the hand in the median distribution isoften secondary. Repetitive strenuous motions, such as industrial activities, weight training, or driving, often provoke the symptoms. Nocturnal symptoms are infrequent. Numbness may affect all or part of the median distribution. Occasionally, patients may insist on emphasizing numbness of the little finger or the “whole hand.”

Acute symptoms should be distinguished from the typical pattern of a more chronic “pain syndrome.” An expanding hematoma such as following venipuncture can result in acute compression of the median nerve by the lacertus fibrosus. Renal dialysis patients with arteriovenous fistulae have been reported to develop median nerve symptoms suddenly that localize to the elbow level. Pronator syndrome may also occur following crushing or contusion of the proximal forearm or stretching of the spastic musculature by casting in patients with cerebral palsy.

Physical Examination

It is important to verify whether these tests mimic or reproduce exactly the symptoms that brought the patient to the physician. This syndrome is most likely to be confused with carpal tunnel syndrome, and unfortunately, the two conditions may occur simultaneously, or one may antedate the other, suggesting a susceptibility factor. Some factors that may help to differentiate between the two syndromes are indicated in Table 80-2. Obviously, careful clinical judgment is required to ensure the correct diagnosis. Indications for surgery depend largely on the severity of the patient’s symptoms. Aside from avoidance of the activities associated with aggravation of the symptoms, there is little available nonoperative treatment. A mixture of lidocaine and hydrocortisone instilled near the nerve may produce temporary beneficial effect and provide an additional diagnostic aid if effective. An increasing number of surgeons have advocated carpal tunnel release before pronator release,5 whereas others are releasing both areas simultaneously.125

TABLE 80-2 Comparison of Findings Between the Carpal Tunnel Syndrome and the Pronator Syndrome

| Carpal Tunnel Syndrome | Pronator Syndrome | |

|---|---|---|

| Nocturnal symptoms | + | − |

| Muscular fatigue | − | + |

| Proximal radiation | ± | + |

| Thumb paresthesias | ± | + |

| Thenar atrophy | + | − |

| Phalen’s sign | + | − |

| Pronator signs | − | + |

| Electromyography | + | − |

Electromyography

EMG findings as an aid in the diagnosis of the pronator syndrome have been disappointing.16 Findings that adequately supported the diagnosis were found in only 10% of patients with the diagnosis of pronator syndrome. Slowed conduction velocity across the median nerve below the elbow is seldom detected. The best explanation for this is the size and complexity of the nerve, which is insufficiently compressed to prevent a stimulus progressing at normal velocities down a significant number of fascicles of the nerve. The slowed impulses in affected fascicles are blurred and dampened in the recording. Muscle studies are seldom specific. Isolated fibrillations, particularly in the pronator teres, have been observed. Insertional changes are often nonspecific. Electrical studies are useful in ruling out the presence of another entrapment site or underlying peripheral neuropathy.

Intraoperative studies of conduction velocities and voltages were carried out before and after median nerve release in 10 forearms in the early part of one series.70 Significant increases in recorded velocities or voltages at the distal electrodes were noted in only five instances after decompression. Newer techniques may improve the diagnostic acuity of EMG, but at this time, the history and physical examination must be relied on for the diagnosis.

Operative Findings

The median nerve seldom shows the flattening, indentation, or pseudoneuroma formation so common at the carpal tunnel. The lacertus fibrosus is usually apparent in its course from the biceps tendon to its interdigitations with the longitudinally directed fibers of the antebrachial fascia over the proximal third of the flexor-pronator muscle group. An indentation of the pronator teres is apparent with passive pronation (see Fig. 80-20). At times, this finding may be dramatic. The compression may even be due to an accessory bicipital aponeurosis. After release of the lacertus fibrosus and antebrachial fascia, the median nerve is apparent lying adjacent to the humeral head of the pronator teres (Fig. 80-22).

The fibrous arch of origin of the flexor digitorum superficialis lies 1 to 2 cm distal to the deep head of the pronator teres (see Fig. 80-22B). This, too, may be a constriction, especially when there is a large sharp edge to the band and hypertrophy of both the deep flexors and overlying muscle groups. This structure can be a cause of pronator syndrome. In a similar fashion, variant or vestigial muscles such as the Gantzer muscle, palmaris profundus, or flexor carpi radialis brevis may act to produce constriction. Less common factors that act to compress the median nerve are vascular malformations or distention of the bicipital bursa. The nerve may be perforated by a branch of the radial artery and accompanying veins or overlain by a taut vascular bridge. Some authors74,129 have recommended microsurgical interfascicular dissection of the median nerve in the distal arm and elbow region in suspected cases of pronator or anterior interosseous nerve syndromes where no obvious sign of median nerve compression is identified.

Anterior Interosseous Nerve Syndrome

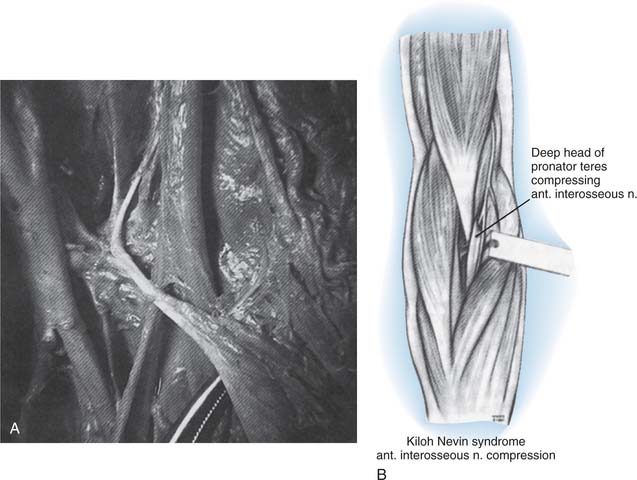

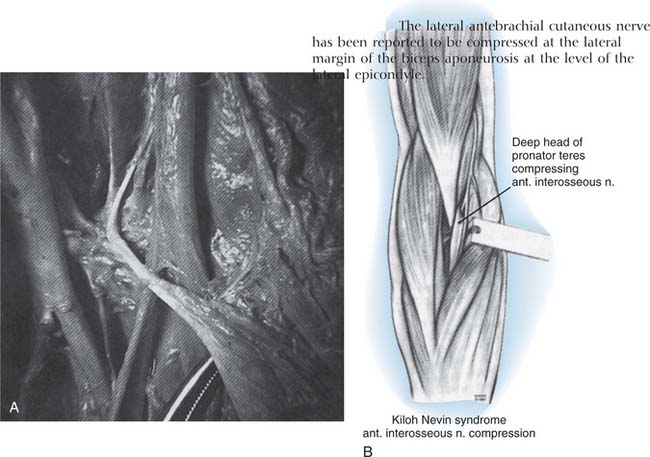

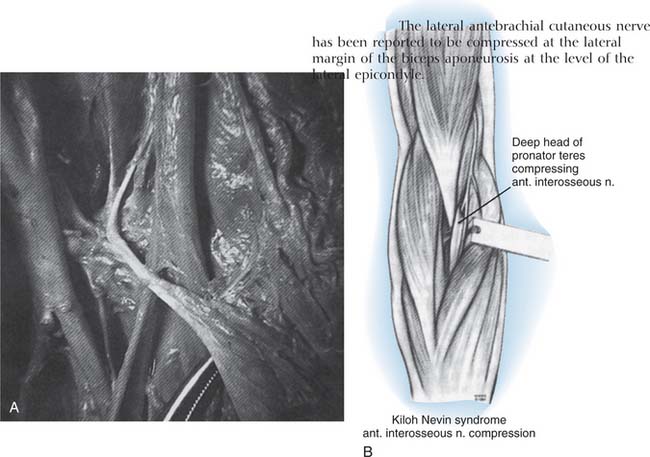

Isolated paresis or paralysis of the anterior interosseous nerve gained modern acceptance following the report of Kiloh and Nevin in 1952 and is often referred to as the Kiloh-Nevin syndrome.91 It was perhaps originally described by Tinel in 1918,186 and a number of authors have cited case reports or small series.48,99,111,131,148,162,167 Several larger series have recently been reported.156,159,166 Both complete and incomplete presentations have been described.76

The cause of this problem may be an acute demyelination episode similar to those seen in the brachial plexus as in Parsonage-Turner syndrome or brachial plexitis.142,199 An initial period of nonoperative therapy is therefore warranted, to allow time for improvement of symptoms which would be characteristic of Parsonage-Turner syndrome, or the development of other neurologic findings, which might suggest another diagnosis.

Symptoms

Commonly, a deep unremitting pain in the proximal forearm initiates the symptoms, which subside within 8 to 12 hours. The patient may then note a lack of dexterity or weakness of pinch that fails to resolve. If the patient was seen previously, diagnoses from tendinous rupture to multiple sclerosis may have been entertained, particularly if the onset has been insidiously painless. Spontaneous improvement has been reported in some instances in which the patient had an apparently demyelinating etiology.58,195

Physical Findings

In complete cases, the findings are those associated with denervation of the classic distribution of the anterior interosseous nerve to the flexor pollicis longus, the index and middle finger flexor digitorum profundus, and the pronator quadratus. The stance of the thumb and index finger when attempting to pinch is characteristic (Fig. 80-23). Because of an inability to flex the distal joints, they are approximated in hyperextension along their distal phalanges. Pinch is weak, and manipulative facility is impaired. Isolated testing shows marked weakness or paralysis of the flexor pollicis longus and index finger flexor digitorum profundus (see Fig. 80-23B). The middle finger is usually less affected, depending on the relative contributions of the ulnar and median nerves to the profundi. Thumb to little finger opposition is unaffected. In incomplete cases, usually the flexor pollicis longus or the index finger profundus is affected. Incomplete lesions are frequently misdiagnosed as a tendon rupture and electrodiagnosis is especially helpful both in establishing neural dysfunction but also excluding polyneuropathy or wider median nerve dysfunction. They may occur spontaneously or follow fracture fixation.88

Tenderness over the proximal forearm is usually absent, and sensory disturbance is not apparent. EMG findings of fibrillations are present in the affected muscles. In one study, all patients had electrical changes; the pronator quadratus was most consistently affected.159

Nerve variations such as the Martin-Gruber anastomosis may occur between the anterior interosseous nerve and the ulnar nerve, as well as between the median and ulnar nerves. These fibers are likely to innervate intrinsic muscle on the radial aspect of the hand. Therefore, it is necessary to differentiate partial apparent ulnar paralysis from the anterior interosseous nerve syndrome.

Operative Findings

The operative findings reported are similar to those described earlier for the pronator syndrome. The usual finding is a constriction due to the tendon or origin of the ulnar head of the pronator teres across the posterolateral aspect of the anterior interosseous nerve as it separates from the median nerve (Fig. 80-24). There may be a fibrous reaction in the area that is probably associated with the acute episode of pain, suggesting a localized vascular reaction such as thrombosis or ischemia.

Preferred Treatment for Exposure of the Median Nerve

If the pronator teres is prolonged proximally, the muscle often covers the median nerve above the elbow. The medial intermuscular septum and the brachial fascia tend to envelop the nerve in this situation. A true ligament of Struthers may be present if there is a supracondylar process. Although such a diagnosis is usually made radiographically, palpation of the lower humerus through this incision may indicate an unsuspected supracondylar process.

CUTANEOUS NERVES

Lateral Antebrachial Nerve

Compression neuropathy of the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve is a recently recognized syndrome.9,30,50,65,143 This cutaneous branch may also be injured at surgery or with injections.201

Relevant Anatomy

The musculocutaneous nerve, after supplying the coracobrachialis, biceps, and brachialis muscles, continues in the interval between the last two muscles as a sensory nerve to supply the skin over the anterolateral aspect of the forearm, often as far as the thenar eminence. It emerges from beneath the biceps tendon laterally and penetrates the brachial fascia just above the elbow crease to course down the forearm (Fig. 80-25).

Clinical Findings

Bassett and Nunley describe both acute and chronic problems.9 A distinct mechanism of injury consisting of elbow hyperextension and pronation or resisted elbow flexion and pronation was elicited from their patients; presumably, the nerve was compressed between the biceps tendon and the brachialis fascia because both the nerve and the tendon were rendered taut by the forearm position. Burning dysesthesia in the distribution of the nerve is seen acutely. In chronic phases, the patient complains of a vague discomfort in the forearm with some dysesthetic qualities that are sometimes made worse by supinopronatory activities with the elbow extended.

On physical examination, a dysesthetic area on the anterolateral aspect of the forearm can be elicited by gently stroking across the skin transversely with a blunt point. Tenderness to direct pressure on the lateral aspect of the bicipital tendon just proximal to the elbow crease is characteristic127; loss of extension and pronation is often exhibited with this maneuver. The sensory action potential may exhibit a prolonged latency or diminished amplitude.50

Medial Antebrachial Cutaneous Nerve

The posterior branch of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve has received some attention because of its course near the medial epicondyle. This has obvious clinical significance. Neuromata occur relatively frequently after ulnar nerve surgery38 but may also occur following treatment of medial epicondylitis.150 A recent anatomic study147 describes the course of this cutaneous nerve and its variations. Rare cases of compressive lesions have also been reported.21,160 Patients present with sensory disturbance in the posteromedial forearm or pain at the medial aspect of the elbow or both.

Posterior Antebrachial Cutaneous Nerve

Nerve lesions of the posterior antebrachial cutaneous branch (a branch of the radial nerve at or near the spiral groove) do occur. Patients may present with isolated sensory abnormalities in the dorsolateral forearm or lateral elbow pain, or both. Several cases22,36,42 have been reported, occurring either spontaneously or following surgery. The nerve emerges from the lateral triceps and has a variable relationship with the lateral intermuscular septum. It then courses over the brachioradialis near the lateral epicondyle. Its course makes it particularly vulnerable in surgery for lateral epicondylitis or posterior interosseous nerve releases, and even following humeral fracture reduction and fixation, demonstrating the nerve’s vulnerability more proximally. Excision of the neuroma or decompression of the nerve branch can relieve the symptoms.

1 Abe M., Ishizu T., Okamoto M., Onomura T. Tardy ulnar nerve palsy caused by cubitus varus deformity. J. Hand Surg. 1995;20A:5.

2 Agnew D.H. Bursal tumor producing loss of power of forearm. Am. J. Med. Sci. 1863;46:404.

3 Al-Qattan M.M. Gantzer’s muscle. An anatomical study of the accessory head of the flexor pollicis longus muscle. J. Hand Surg. 1996;21B:269.

4 Amadio P.C. Anatomical basis for a technique of ulnar nerve transposition. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 1986;8:155.

5 Amadio P.C. Operations I no longer do (well, hardly ever). J. Hand Surg. 2002;27B:155.

6 Apfelberg D.B., Larson S.J. Dynamic anatomy of the ulnar nerve at the elbow. Plast. Reconst. Surg. 1973;51:76.

7 Barber K.W.Jr., Bianco A.J.Jr., Soule E.H., MacCarty C.S. Benign extramural soft tissue tumors of the extremities causing compression of nerves. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1982;44A:98.

8 Bartels R.H., Verhagen W.I., van der Wilt G.J., Meulstee J., van Rossum L.G., Grotenhuis J.A. Prospective randomized controlled study comparing simple decompression versus anterior subcutaneous transposition for idiopathic neuropathy of the ulnar nerve at the elbow: Part 1. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:522.

9 Bassett F.H., Nunley J.A. Compression of the musculocutaneous nerve at the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1982;64A:1050.

10 Biggs M., Curtis J.A. Randomized, prospective study comparing ulnar neurolysis in situ with submuscular transposition. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:296.

11 Bowen T.L., Stone K.H. Posterior interosseous nerve paralysis caused by a ganglion at the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1966;48B:774.

12 Boyes J.H. Bunnell’s Surgery of the Hand, 5th ed., Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co.; 1970:418.

13 Braun R.M., Spinner R.J. Spontaneous bilateral median nerve compression in the distal arm. J. Hand Surg. 1991;16A:244.

14 Brooks D.M. Nerve compression by simple ganglia. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1952;34B:391.

15 Bryan F.S., Miller L.S., Panijaganond P. Spontaneous paralysis of the posterior interosseous nerve: A case report and review of the literature. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1971;80:9.

16 Buchthal F., Rosenflack A., Trojaborg W. Electrophysiological findings in entrapment of the median nerve at wrist and elbow. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1974;37:340.

17 Busa R., Adani R., Marcuzzi A., Caroli A. Acute posterior interosseous nerve palsy caused by a synovial haemangioma of the elbow joint. J. Hand Surg. 1995;20B:652.

18 Campbell C.S., Wulf R.F. Lipoma producing a lesion of the deep branch of the radial nerve. J. Neurosurg. 1954;11:310.

19 Capener N. Posterior interosseous nerve lesions. Proceedings of the Second Hand Club. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1964;46B:361.

20 Capener N. The vulnerability of the posterior interosseous nerve of the forearm. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1966;48B:770.

21 Chang C.W., Oh S.J. Medial antebrachial cutaneous neuropathy: Case report. Electromyogr. Clin. Neurophys. 1988;28:3.

22 Chang C.W., Oh S.J. Posterior antebrachial cutaneous neuropathy. Case report. Electromyogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1990;30:3.

23 Childress H.M. Recurrent ulnar-nerve dislocation at the elbow. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1975;108:168.

24 Clark C.B. Cubital tunnel syndrome. J. A. M. A. 1979;241:801.

25 Cohen B.E. Simultaneous posterior and anterior interosseous nerve syndromes. J. Hand Surg. 1982;7:398.

26 Comtet J.J., Chambaud D. Paralysie “spontanée” du nerf inter-osseoux posterier par lesion inhabituelle. Deux observations. Rev. Chir. Orthop. 1975;61:533.

27 Comtet J.J., Chambaud D., Genety J. La compression de la branche posterier du nerf radial. Une etiologie meconnue de certaines paralysies et de certaines spicondylalgies rebelles. Nouv. Presse Med. 1976;5:1111.

28 Craven P.R.Jr., Green D.P. Cubital tunnel syndrome. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1980;62A:986.

29 Dahners L.E., Wood F.M. Anconeus epitrochlearis, a rare cause of cubital tunnel syndrome: a case report. J. Hand Surg. 1984;9A:579.

30 Davidson J.J., Bassett F.H.III, Nunley J.A. Musculocutaneous nerve entrapment revisited. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7:250.

31 Davies F., Laird M. The supinator muscle and the deep radial (posterior interosseous) nerve. Anat. Rec. 1948;101:243.

32 Dawson D.M., Hallett M., Millender L.H. Entrapment Neuropathies, 2nd ed. Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1990.

33 Dellon A.L. Techniques for successful management of ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow. Neurosurg. Clin. North Am. 1991;2:57.

34 Dellon A.L., Coert J.H. Results of the musculofascial lengthening technique for submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve at the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85A:1314.

35 Dellon A.L., Coert J.H. Results of the musculofascial lengthening technique for submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve at the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2004;86A(suppl 1 Pt 2):169.

36 Dellon A.L., Kim J., Ducic I. Painful neuroma of the posterior cutaneous nerve of the forearm after surgery for lateral humeral epicondylitis. J. Hand Surg. 2004;29A:387.

37 Dellon A.L., Mackinnon S.E. Radial-sensory nerve entrapment in the forearm. J. Hand Surg. 1986;11A:199.

38 Dellon A.L., Mackinnon S.E. Injury to the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve during cubital tunnel surgery. J. Hand Surg. 1985;10B:33.

39 Dellon A.L., Mackinnon S.E. Musculoaponeurotic variations along the course of the median nerve in the proximal forearm. J. Hand Surg. 1987;12B:359.

40 Dennny-Brown D., Brenner C. Paralysis of nerve induced by direct pressure and by tourniquet. Arch. Neurol. Psychiatry. 1944;51:1.

41 Dharapak C., Nimberg G.A. Posterior interosseous nerve compression. Report of a case caused by traumatic aneurysm. Clin. Orthop. 1974;101:225.

42 Doyle J.J., David W.S. Posterior antebrachial cutaneous neuropathy associated with lateral elbow pain. Muscle Nerve. 1993;16:1417.

43 Dreyfuss U., Kessler I. Snapping elbow due to dislocation of the medial head of the triceps. A report of two cases. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1978;60B:56.

44 Eaton R.G., Crowe J.F., Parkes J.C.III. Anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve using a non-compressing fasciodermal sling. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1980;62A:820.

45 Erhlich G.E. Antecubital cysts in rheumatoid arthritis: a corollary to popliteal (Baker’s) cysts. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1972;54A:165.

46 Escobar P.L. Short segment stimulations in ulnar nerve lesions around elbow. Orthop. Rev. 1983;12:65.

47 Eversmann W.W.Jr. Entrapment and compression neuropathies. In: Green D.P., editor. Operative Hand Surgery. 2nd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1988:1423.

48 Farber J.S., Bryan R.S. The anterior interosseous nerve syndrome. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1968;50A:521.

49 Feindel W., Stratford J. The role of the cubital tunnel in tardy ulnar palsy. Can. J. Surg. 1958;1:296.

50 Felsenthal G., Mondell D.L., Reischer M.A., Mack R.H. Forearm pain secondary to compression syndrome of the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1984;65:139.

51 Flory P.J., Berger A. Die akzessorische brachialissehneselten Ursache des Pronator Teres-Syndroms. Handchir. 1985;17:270.

52 Foster R.J., Edshage S. Factors related to outcome of surgically managed compressive ulnar neuropathy at the elbow level. J. Hand Surg. 1981;6:181.

53 Freundlich B.D., Spinner M. Nerve compression syndrome in derangements of the proximal and distal radioulnar joints. Bull. Hosp. Joint Dis. 1968;19:38.

54 Frohse F., Frankel M. Die Muskeln des menschlichen Ames. In: Bardelenbens Handbuch der Anatomie des Nenschlichen. Jena: Fisher; 1908.

55 Froimson A.I., Zahrawi F. Treatment of compression neuropathy of the ulnar nerve at the elbow by epicondylectomy and neurolysis. J. Hand Surg. 1980;5:391.

56 Fujioka H., Nakabayashi Y., Hirata S., Go G., Nishi S., Mizuno K. Analysis of tardy ulnar nerve palsy associated with cubitus varus deformity after a supracondylar fracture of the humerus: a report of four cases. J. Orthop. Trauma. 1995;9:435.

57 Gabel G.T., Amadio P.C. Reoperation for failed decompression of the ulnar nerve in the region of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1990;72A:213.

58 Gaitzsch G., Chamay A. Paralytic brachial neuritis or Parsonage-Turner syndrome anterior interosseous nerve involvement. Report of three cases. Ann. Chir. Main. 1986;5:288.

59 Gantzers C.F.L. De Musculorum Varietates, thesis. Berlioni: J. F. Starckie, 1813.

60 Gelberman R.H., Yamaguchi K., Hollstien S.B., Winn S.S., Heidenreich F.P.Jr., Bindra R.R., Hsieh P., Silva M.J. Changes in interstitial pressure and cross-sectional area of the cubital tunnel of the ulnar nerve with flexion of the elbow. An experimental study in human cadavera. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1998;80A:492.

61 Gervasio O., Gambardella G., Zaccone C., Branca D. Simple decompression versus anterior submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerve in severe cubital tunnel syndrome: a prospective randomized study. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:108.

62 Gessini L., Jandolo B., Pietrangeli A. Entrapment neuropathies of the median nerve at and above the elbow. Surg. Neurol. 1983;19:112.

63 Geutjens G.G., Langstaff R.J., Smith N.J., Jefferson D., Howell C.J., Barton N.J. Medial epicondylectomy or ulnar nerve transposition for ulnar neuropathy at the elbow? J. Bone Joint Surg. 1996;78B:777.

64 Gilliatt B.W., Ochoa J., Rudge P., Neary D. The cause of nerve damage in acute compression. Trans. Am. Neurol. Assoc. 1974;99:71.

65 Gillingham B.L., Mack G.R. Compression of the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve by the biceps tendon. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5:330.

66 Goldman S., Honet J.C., Sobel R., Goldstein A.S. Posterior interosseous nerve palsy in the absence of trauma. Arch. Neurol. 1969;21:435.

67 Graf P., Hawe W., Biemer E. Gefabversorgung des nulnaris nach Neurolyse im Ellenbogenbereich. Handchir. 1986;18:204.

68 Gunther S.F., DiPasquale D., Martin R. The internal anatomy of the median nerve in the region of the elbow. J. Hand Surg. 1992;17A:648.

69 Harrelson J.M., Newman M. Hypertrophy of the flexor carpi ulnaris as a cause of ulnar-nerve compression in the distal part of the forearm. Case report. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1975;57A:554.

70 Hartz C.R., Linscheid R.L., Gramse R.R., Daube J.R. Pronator teres syndrome: compressive neuropathy of the median nerve. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1981;63A:885.

71 Hashizume H., Inoue H., Nagashima K., Hamaya K. Posterior interosseous nerve paralysis related to focal radial nerve constriction secondary to vasculitis. J. Hand Surg. 1993;18B:757.

72 Hashizume H., Nishida K., Nanba Y., Shigeyama Y., Inoue H., Morito Y. Non-traumatic paralysis of the posterior interosseous nerve. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1996;78B:771.

73 Hashizume H., Nishida K., Yamamoto K., Hirooka T., Inoue H. Delayed posterior interosseous nerve palsy. J. Hand Surg. 1995;20B:655.

74 Haussmann P., Patel M.R. Intraepineurial constriction of nerve fascicles in pronator syndrome and anterior interosseous nerve syndrome. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 1996;27:339.

75 Haws M., Brown R.E. Bilateral snapping triceps tendon after bilateral ulnar nerve transposition for ulnar nerve subluxation. Ann. Plast. Surg. 1995;34:550.

76 Hill H.A., Howard F.M., Huffer B.R. The incomplete anterior interosseous nerve syndrome. J. Hand Surg. 1985;10A:4.

77 Hirachi K., Kato H., Minami A., Kasashima T., Kaneda K. Clinical features and management of posterior interosseous nerve palsy. J. Hand Surg. 1998;23B:413.

78 Hobhouse N., Heald C.B. A case of posterior interosseous paralysis. Br. Med. J. 1936;1:841.

79 Hoffmann R., Siemionow M. The endoscopic management of cubital tunnel syndrome. J. Hand Surg. 2006;31B:23.

80 Hollinshead W.H. Anatomy for Surgeons, Vol. 3, The Back and Limbs, 3rd ed. New York: Harper and Row, 1982.

81 Jabaley M.E., Wallace W.H., Heckler F.R. Internal topography of major nerves of the forearm and hand: a current view. J. Hand Surg. 1980;5:1.

82 Jebson P.J.L., Engber W.D. Radial tunnel syndrome: long-term results of surgical decompression. J. Hand Surg. 1997;22A:889.

83 Johnson R.K., Spinner M., Shrewsbury M.M. Median nerve entrapment syndrome in the proximal forearm. J. Hand Surg. 1979;4:48.

84 Jones R.E. Medial epicondylectomy for ulnar nerve compression syndrome at the elbow. Clin. Orthop. 1979;139:174.

85 Kaempffe F.A., Farbach J. A modified surgical procedure for cubital tunnel syndrome: partial medial epicondylectomy. J. Hand Surg. 1998;23A:492.

86 Kane E., Kaplan E.B., Spinner M. Observations of the course of the ulnar nerve in the arm. Ann. Chir. 1973;27:487.

87 Kaplan E.B. Functional and Surgical Anatomy of the Hand, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co., 1965.

88 Keogh P., Khan H., Cooke E., McCoy G. Loss of flexor pollicis longus function after plating of the radius. J. Hand Surg. 1997;22B:375.

89 Keret D., Porter K.M. Synovial cyst and ulnar nerve entrapment: a case report. Clin. Orthop. 1984;188:213.

90 Khoo D., Carmichael S.W., Spinner R.J. Ulnar nerve anatomy and compression. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 1996;27:317.

91 Kiloh L.G., Nevin S. Isolated neuritis of the anterior interosseous nerve. Br. Med. J. 1952;1:859.

92 Kopell H.P., Thompson W.A.I. Pronator syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 1958;259:713.

93 Kopell H.P., Thompson W.A. Peripheral Entrapment Neuropathies. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1963.

94 Kotani H., Miki T., Senzoku F., Nakagawa Y., Ueo T. Posterior interosseous nerve paralysis with multiple constrictions. J. Hand Surg. 1995;20A:15.

95 Krishnan K.G., Pinzer T., Schackert G. A novel endoscopic technique in treating single nerve entrapment syndromes with special attention to ulnar nerve transposition and tarsal tunnel release: clinical application. Neurosurgery. 2006;59(1 Suppl 1):ONS89.

96 Kuszynski K. Functional micro-anatomy of the peripheral nerve trunks. Hand. 1974;6:1.

97 Laha R.K., Lunsford L.D., Dujovny M. Lacertus fibrosus compression of the median nerve. A case report. J. Neurosurg. 1978;48:838.

98 Lahey M.D., Aulicino P.L. Anomalous muscles associated with compression neuropathies. Orthop. Rev. 1986;15:19.

99 Lake P.A. Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome. J. Neurosurg. 1974;41:306.

100 Learmonth J.R. A variation of the radial branch of the musculo-spiral nerve. J. Anat. 1919;53:371.

101 Learmonth J.R. Technique for transplanting the ulnar nerve. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1942;75:792.

102 LeDouble A.F. Traite des Variations du Systeme Musculaire de l Homme. Paris: Schleicher, 1897.

103 Leffert R.D. Anterior submuscular transposition of the ulnar nerves by the Learmonth technique. J. Hand Surg. 1982;7:147.

104 Leffert R.D., Dorfman H.D. Antecubital cyst in rheumatoid arthritis. Surgical findings. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1972;54A:1555.

105 Lichter R.L., Jacobsen T. Tardy palsy of the posterior interosseous nerve with a Monteggia fracture. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1975;57A:124.

106 Lipscomb P.R., Burleson R.J. Vascular and neural complications in supracondylar fractures in children. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1955;37A:487.

107 Lister G.D., Belsole R.B., Kleinert H.E. The radial tunnel syndrome. J. Hand Surg. 1979;4:52.

108 Lluch A.L. Ulnar nerve entrapment after anterior transposition at elbow. N. Y. State J. Med. 1975;75:75.

109 Lundborg G. Ischemic nerve injury. Experimental studies on intraneural microvascular pathophysiology and nerve function in a limb subjected to temporary circulatory arrest. Scand. J. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. [Suppl.]. 1970;6:1.

110 Macnicol M.F. Extraneural pressures affecting the nerve at the elbow. Hand. 1982;14:5.

111 Maeda K., Miura T., Komada T., Chiba A. Anterior interosseous nerve paralysis. Report of 13 cases and review of Japanese literature. Hand. 1977;9:165.

112 Mangini U. Flexor pollicis longus muscle. Its morphology and clinical significance. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1960;42A:467.

113 Mannerfelt L. Studies on the hand in ulnar nerve paralysis. A clinical-experimental investigation in normal and anomalous innervation. Acta Orthop. Scand. (Suppl. 87):1966.

114 Marmor L., Lawrence J.F., Dubois E. Posterior interosseous nerve paralysis due to rheumatoid arthritis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1967;49A:381.

115 Marquis J.W., Bruwer A.J., Keith H.M. Suparcondyloid process of the humerus. Proc. Staff Meeting Mayo Clin. 1957;37:691.

116 Marshall S.C., Murray W.R. Deep radial nerve palsy associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1974;103:157.

117 Martinelli P., Gabellini A.S., Poppi M., Gallassi R., Pozzatti E. Pronator syndrome due to thickened bicipital aponeurosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1982;45:181.

118 Mayer J.H., Mayfield P.H. Surgery of the posterior interosseous branch of the radial nerve. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1947;84:979.

119 Millender L.H., Nalebuff E.A., Holdsworth D.E. Posterior interosseous nerve syndrome secondary to rheumatoid synovitis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1973;55A:753.

120 Miller R.G. Acute versus chronic compressive neuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 1984;7:427.

121 Morrey B.F. Reoperation for failed surgical treatment of refractory lateral epicondylitis. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1992;1:47.

122 Morris A.H. Irreducible Monteggia lesion with radial-nerve entrapment. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1964;46A:608.

123 Morris H.H., Peters B.H. Pronator syndrome: Clinical and electrophysiological features in seven cases. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1976;39:461.

124 Mowell J.W. Posterior interosseous nerve injury. Int. Clin. 1921;2:188.

125 Mujadzic M., Papanicolaou G., Young H., Tsai T.M. Simultaneous surgical releases of ipsilateral pronator teres and carpal tunnel syndromes. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2007;119:2141.

126 Mulholland R.C. Non-traumatic progressive paralysis of the posterior interosseous nerve. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1966;48B:781.

127 Naam N.H., Massoud H.A. Painful entrapment of the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve at the elbow. J. Hand Surg. 2004;29A:1148.

128 Nabhan A., Ahlhelm F., Kelm J., Reith W., Schwerdtfeger K., Steudel W.I. Simple decompression or subcutaneous anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve for cubital tunnel syndrome. J. Hand Surg. 2005;30B:521.

129 Nagano A., Shibata K., Tokimura H., Yamamoto S., Tajiri Y. Spontaneous anterior interosseous nerve palsy with hourglass-like fascicular constriction within the main trunk of the median nerve. J. Hand Surg. 1996;21A:266.

130 Nakamura I., Hoshino Y. Extraneural hemangioma: a case report of acute cubital tunnel syndrome. J. Hand Surg. 1997;21A:1097.

131 Nakano K.K., Lundergan C., Okihiro M.M. Anterior interosseous nerve syndromes. Arch. Neurol. 1977;34:477.

132 Narakas A.O. The role of thoracic outlet syndrome in the double crush syndrome. Ann. Chir. Main Memb. Super. 1990;9:331.

133 Nicolle F.V., Woolhouse F.M. Nerve compression syndromes of the upper limb. J. Trauma. 1965;5:313.

134 Nielsen H.O. Posterior interosseous nerve paralysis caused by fibrous band compression at the supinator muscle: a report of four cases. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1976;47:304.

135 Nouhan R., Kleinert J.M. Ulnar nerve decompression by transposing the nerve and Z-lengthening the flexor-pronator origin. J. Hand Surg. 1997;22A:127.

136 Ochoa J. Schwann cell and myelin changes caused by some toxic agents and trauma. Proc. Soc. Med. 1976;67:3.

137 O’Driscoll S.W., Horii E., Carmichael S.W., Morrey B.F. The cubital tunnel and ulnar neuropathy. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1991;73B:613.

138 Omer G., Spinner M., Van Beek A.L. Peripheral Nerve Problems, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Co., 1998.

139 Omer G.E., Spinner M. Peripheral nerve testing and suture techniques. In: American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, Vol. 24. Instructional Course Lectures. St. Louis: C.V. Mosby Co.; 1975:122.

140 Osbourne G. Compression neuritis of the ulnar nerve at the elbow. Hand. 1970;2:10.

141 Osbourne G. The surgical treatment of tardy ulnar neuritis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1957;39B:782.

142 Parsonage M.J., Turner J.W. Neuralgic amyotrophy: The shoulder girdle syndrome. Lancet. 1948;1:973.

143 Patel M.R., Bassini L., Magill R. Compression neuropathy of the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve. Orthopedics. 1991;14:173.

144 Porcellini G., Paladini P., Campi F., Merolla G. Arthroscopic neurolysis of the ulnar nerve at the elbow. Chir. Organi Mov. 2005;90:191.

145 Pribyl C.R. Use of the medial intermuscular septum as a fascial sling during anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve. J. Hand Surg. 1998;23A:500.

146 Pritchard D.J., Linscheid R.L., Svien H.J. Intraarticular median nerve entrapment with dislocation of the elbow. Clin. Orthop. 1973;90:100.

147 Race C.M., Saldana M.J. Anatomic course of the medial cutaneous nerves of the arm. J. Hand Surg. 1991;16A:48.

148 Rask M.R. Anterior interosseous nerve entrapment: report of seven cases. Clin. Orthop. 1979;142:176.

149 Reis N.D. Anomalous triceps tendon as a cause for snapping elbow and ulnar neuritis: a case report. J. Hand Surg. 1980;5:361.

150 Richards R.R., Regan W.D. Medial epicondylitis caused by injury to the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve: a case report. Can. J. Surg. 1989;32:366.

151 Richmond D.A. Lipoma causing a posterior nerve lesion. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1953;35B:83.

152 Riordan D.C. Radial nerve paralysis. Orthop. Clin. N. Am. 1974;5:283.

153 Roles N.C., Maudsley R.H. Radial tunnel syndrome. Resistant tennis elbow as a nerve entrapment. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1972;54B:499.

154 Rolfsen L. Snapping triceps tendon with ulnar neuritis. Report on a case. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1970;41:74.

155 Salsbury C.R. The nerve to the extensor carpi radialis brevis. J. Surg. 1938;26:95.

156 Schantz K., Riegels-Nielsen P.R. The anterior interosseous nerve syndrome. J. Hand Surg. 1992;17B:510.

157 Seddon H.J. Three types of nerve injury. Brain. 1943;66:237.

158 Seradge H., Owen H. Cubital tunnel release with medial epicondylectomy factors influencing the outcome. J. Hand Surg. 1998;23A:483.

159 Seror P. Anterior interosseous nerve lesions. Clinical and electrophysiological features. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1996;78B:238.

160 Seror P. Forearm pain secondary to compression of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve at the elbow. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehab. 1993;74:540.

161 Seyfarth H. Primary myoses in the mpronator teres as cause of lesion of the n. medianus (the pronator syndrome). Acta Psychiatr. Neurol. Scand. Suppl. 1951;74:251.

162 Sharrard W.J.W. Anterior interosseous neuritis. Report of a case. J. Bone Joint. Surg. 1968;50B:804.

163 Sharrard W.J.W. Posterior interosseous neuritis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1966;48B:777.

164 Siqueira M.G., Martin R.S. The controversial arcade of Struthers. Surg. Neurol. 2005;64(S1):17.

165 Somerville E.W. Pain in the upper limb. Proceedings of the British Orthopaedic Association. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1963;45B:621.

166 Sood M.K., Burke F.D. Anterior interosseous nerve palsy. A review of 16 cases. J. Hand Surg. 1997;22B:64.

167 Spinner M. The anterior interosseous nerve syndrome: with special attention to its variations. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1970;52A:84.

168 Spinner M. The arcade of Frohse and its relationship to posterior interosseous nerve paralysis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1968;50B:809.

169 Spinner M. Injuries to the Major Branches of Peripheral Nerves of the Forearm, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Co., 1978.

170 Spinner M. Nerve decompression. In: Morrey B.F., editor. Master Techniques in Orthopedic Surgery. The Elbow. New York: Raven Press, 1994.

171 Spinner M., Freundlich B.D., Teicher J. Posterior interosseous nerve palsy as a complication of Monteggia fracture in children. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1968;58:141.

172 Spinner M., Kaplan E.B. The relationship of the ulnar nerve to the medial intermuscular septum in the arm and its clinical significance. Hand. 1976;8:239.

173 Spinner R.J., Berger R.A., Dyck P.J., Carmichael S.W., Nunley J.A. Isolated paralysis of the extensor digitorum communis associated with the posterior (Thompson) approach to the proximal radius. J. Hand Surg. 1998;23A:135.

174 Spinner R.J., Carmichael S.W., Spinner M. Partial median nerve entrapment in the distal arm because of an accessory bicipital aponeurosis. J. Hand Surg. 1991;16A:236.

175 Spinner R.J., Goldner R.D. Snapping of the medial head of the triceps and recurrent dislocation of the ulnar nerve. Anatomical and dynamic factors. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1998;80A:239.

176 Spinner R.J., Spinner M. Tardy posterior interosseous nerve palsy due to childhood osteomyelitis: a case report. J. Hand Surg. 1997;22A:1049.

177 Sponseller P.D., Engber W.D. Double-entrapment radial tunnel syndrome. J. Hand Surg. 1983;8A:420.

178 Steiger R., Vogelin E. Compression of the radial nerve by an occult ganglion. Three case reports. J Hand Surg. 1998;23B:420.

179 Strachan J.C.H., Ellis B.W. Vulnerability of the posterior interosseous nerve during radial head resection. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1971;53B:320.

180 Struthers J. On a peculiarity of the humerus and humeral artery. Monthly J. Med. Sci. 1848;8:264.

181 Suematsu N., Hirayama T. Posterior interosseous nerve palsy. J. Hand Surg. 1998;23B:104.

182 Sunderland S. The innervation of the flexor digitorum profundus and lumbrical muscles. Anat. Rec. 1945;83:317.

183 Sunderland S. Nerve lesions in the carpal tunnel syndrome. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1976;39:615.

184 Sunderland S. Nerves and Nerve Injuries. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins Co, 1968;749.

185 Swiggett R., Ruby L.K. Median nerve compression neuropathy of the lacertus fibrosus: report of three cases. J. Hand Surg. 1986;11A:700.

186 Tinel J. Nerve Wounds. New York: William Wood, 1918;183.

187 Tsai T.M., Chen I.C., Majd M.E., Lim B.H. Cubital tunnel release with endoscopic assistance: results of a new technique. J. Hand Surg. 1999;24A:21.

188 Uchida Y., Sugioka Y. Ulnar nerve palsy after supracondylar humerus fracture. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1990;61:118.

189 Vanderpool D.W., Chalmers J., Lamb D.W., Whiston T.B. Peripheral compression lesions of the ulnar nerve. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1968;50B:792.

190 Wadsworth T.G. The external compression syndrome of the ulnar nerve at the cubital tunnel. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1977;124:189.