CHAPTER 82 Neoplasms of the Elbow

INTRODUCTION

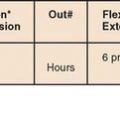

Most benign and malignant tumors of bone and soft tissue are relatively rare, and their occurrence in the region of the elbow is even more unusual. Although there are no valid statistics on soft tissue tumors, compilation of data from the files of the Mayo Clinic until December 2003 indicates that only 1% or so of bone tumors occur at the elbow (Table 82-1). Hence, no single entity is likely to be encountered very often at this site.

| Type of Tumor | Number at Elbows | Total |

|---|---|---|

| Benign | ||

| Osteoid osteoma | 25 | 397 |

| Osteochondroma | 16 | 884 |

| Giant cell tumor | 13 | 682 |

| Chondromyxoid fibroma | 2 | 50 |

| Osteoblastoma | 1 | 108 |

| Malignant | ||

| Malignant lymphoma | 38 | 905 |

| Ewing sarcoma | 15 | 611 |

| Osteosarcoma | 16 | 1984 |

| Fibrosarcoma | 3 | 285 |

| Angiosarcoma | 1 | 109 |

| Chondrosarcoma | 6 | 1080 |

| Malignancy in giant cell tumor | 2 | 39 |

| Malignant fibrous histiocytoma | 1 | 98 |

| Myeloma | 19 | 1069 |

*Does not include patients with multiple exostoses.

Unfortunately, comparable figures are not available for benign and malignant soft tissue tumors, although our impression is that the most common benign soft tissue tumor in the elbow region is the lipoma. Ganglia and myxomas are also occasionally seen in this region. Of the malignant soft tissue tumors, epithelioid sarcoma and synovial sarcoma are probably the most frequently encountered at this joint. The locally aggressive desmoid tumor may also occur at or near the elbow. Metastatic disease usually originates from the breast or kidneys.55

Tumors that occur in the region of the elbow are unique in that because there are a relatively large number of important structures in a relatively small and confined area, there is little normal tissue that can be spared; and it may be difficult or impossible to remove a tumor with a margin of normal tissue on all sides without severely compromising the function of the forearm and hand. In this respect, tumors that occur at the elbow, particularly those in the antecubital fossa, are comparable with tumors that occur in the region of the knee. However, the upper extremity is probably considered more important by most patients and their physicians; hence, amputation surgery is probably less likely to be carried out for these tumors than for those of the lower extremity. In addition, it is generally considered difficult to fit a patient with an upper limb prosthesis; and even if upper limb prosthetic devices are prescribed, patients are often reluctant to use them. In contrast, most patients readily accept the use of a lower limb prosthesis. An amputation may be required for aggressive or malignant tumors to achieve adequate surgical margins, and yet both the patient and the physician may be reluctant to accept this radical treatment. Finally, as with traumatic conditions, the tumor or its treatment often renders the elbow stiff and restricts function.27,54

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

Following the clinical examination, radiographs in at least two planes should be obtained.22 Computed tomography (CT), with a comparison of the opposite elbow joint, may yield useful information, particularly in terms of planning for the surgical procedure. The authors have not found the performance of routine arteriography to be particularly helpful in this or any other site; however, if one needs to know the relationship of the tumor to the adjacent major vessels, contrast material can be used when CT is performed, thereby supplying this information more simply and safely than by performing routine arteriography.

Magnetic resonance imaging has proved to be particularly valuable in the assessment of both bone and soft tissue tumors in most areas, including the elbow. Soft tissue tumors can be defined as to the extent of disease and their relationships with major neurovascular structures. Information about the extent of medullary involvement can be ascertained for bone tumors.

STAGING

The staging system of Enneking and colleagues,24 which includes both soft tissue and bone sarcomas, is useful. This system has two main factors, the first of which is the biologic potential of the lesion. If the lesion is benign, it is labeled G0. If it is malignant, it is judged to be either a low-grade (G1) or a high-grade (G2) lesion; the high-grade lesions have a greater potential for metastatic spread. The second factor is the anatomic site of the lesion; that is, whether it is entirely within a surgical compartment (T1) or whether it extends outside the compartment (T2). With these classifications, a low-grade malignant tumor that is entirely within a single compartment is a 1A lesion; a low-grade lesion that extends into a second compartment is a 1B lesion; a high-grade malignant tumor that is confined to a single compartment is a 2A lesion; and a high-grade tumor that extends into a second compartment is a 2B lesion. Any tumor that shows evidence of metastatic spread is considered a stage 3 lesion.

The terminology suggested by Enneking23 describing surgical procedures is now generally accepted. Thus, if a lesion is entered at surgery, the procedure should be considered an intralesional resection; if a tumor is “shelled out,” the procedure should be considered a marginal resection; and if there is a margin of normal tissue on all aspects of the resected specimen, the operation should be considered a wide excision. For the procedure to be judged a radical resection, all the structures within the involved compartment must be resected. When the lesion involves bone, the entire bone must be removed if the procedure is to be considered a radical resection.

PROSTHETIC REPLACEMENT

With improved designs and techniques, we have improved our outcomes with the use of prosthetic replacement for both primary and metastatic diseases.3,54 The majority (90%) were treated for metastatic diseases. Satisfactory outcomes may be expected given that the overall prognosis of these patients is guarded, with a mean survival time of only 3 years3 (Fig. 82-1).

BONE TUMORS

BENIGN BONE TUMORS

Osteoid Osteoma and Osteoblastoma

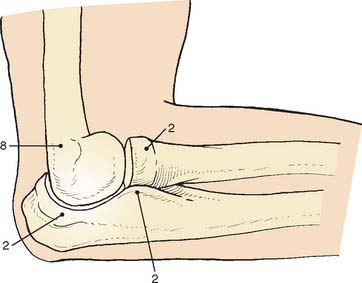

Osteoid osteoma arising in an intra-articular location is relatively uncommon; however, it may occur in the region of the elbow. It is relatively common at the elbow, but only a few reports on the presentation,36 diagnosis,33 and management41 have appeared. This small benign bone tumor occurs in patients of any age, most commonly children and young adults. As with most bone tumors, boys and men are more commonly affected than girls and women. Unremitting pain is the usual symptom for which the patient seeks medical attention; however, progressive loss of motion may also be a characteristic feature. Pain during the night is particularly prominent. Aspirin may afford very dramatic relief of pain, a fact that may even suggest the diagnosis of osteoid osteoma. Occasionally, the pain may be experienced at a site remote from the lesion. Another peculiar feature of this tumor is its occasional association with atrophy of the adjacent soft tissues. In the Mayo Clinic’s experience with 14 such cases, eight have occurred in the distal humerus, four in the ulna (two coronoid, two olecranon), and two in the radial head–neck region60 (Fig. 82-2).

As noted previously, when osteoid osteoma occurs at or near the elbow joint, there is characteristically loss of some flexion or extension, but pronation and supination are preserved. In addition, there may be a synovial reaction that may further confuse the diagnosis. The most striking feature of these tumors is the prolonged average time required for making the diagnosis. In the Mayo Clinic’s experience, the delay to diagnosis averaged almost 2 years.60

The osteoid osteoma, by definition, is small, usually no more than 1.5 cm in diameter. Lesions that are clinically and histologically similar but are 2 cm or more in diameter are referred to as osteoblastomas; these lesions have clinical features somewhat different from those of osteoid osteoma,48 but loss of motion is a common feature.8,27 Osteoid osteoma is small when first encountered and remains small,30 further complicating the diagnosis.

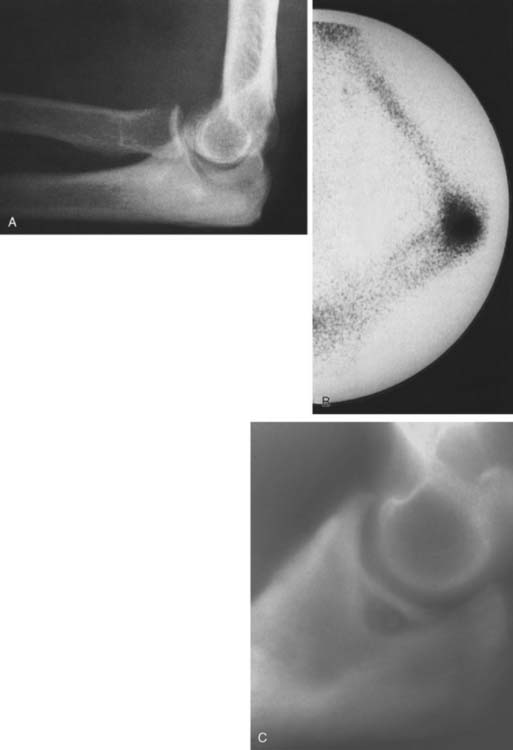

An extensive diagnostic evaluation is usually required in determining the precise location of the osteoid osteoma.12,34 When the patient complains of unremitting pain in the elbow, plain radiographs are obtained (Fig. 82-3). These may or may not reveal the presence of the tumor. The lesion typically appears as a central small nidus, which is a radiolucent area usually surrounded by an area of sclerosis. It is this sclerosis that is usually seen38; the central area of the nidus is more difficult to identify. When the lesion is located on the surface of the bone, there may be periosteal new bone formation thatfurther obscures the nidus.36 Cronemeyer and colleagues13 described an unusual radiographic feature of osteoid osteoma in the elbow joint—subperiosteal new bone formation in adjacent bones; for example, an osteoid osteoma in the distal end of the humerus that exhibits periosteal new bone formation in the proximal radius and ulna.13 These authors concluded that “awareness of this association will prevent misdiagnosis of the benign neoplasm as an inflammatory arthritis.”

Technetium-99m scintigraphy has been helpful in locating these lesions.33 If technetium-99m scintigraphy reveals no abnormality, an osteoid osteoma is unlikely; however, if the bone scan is positive, further diagnostic studies of the involved area should be undertaken (Fig. 82-4). If there is any significant synovial reaction, there may be increased uptake owing to the synovitis as well as to the lesion itself.51,52 Sometimes, multiple radiographs must be taken before the lesion can be identified. Today, CT is the diagnostic standard, however, if the tumor is so small it may be missed on this examination.55

Grossly, there is usually some sclerotic bone surrounding a central nidus. This nidus may be somewhat redder than the surrounding cortical bone and has been described as having the appearance of a small cherry. It is sometimes helpful to obtain radiographs of the excised block of tissue before the pathologist cuts into the block. Microscopic examination of the surrounding bone shows no unusual features; the nidus itself consists of a network of osteoid trabeculae (see Fig. 82-3).

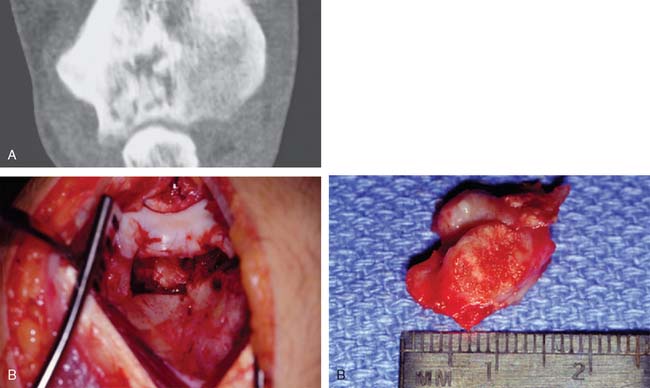

Treatment.

In the past, the treatment of osteoid osteoma was surgical excision of the nidus. It is not necessary to remove all of the sclerotic bone. The main problem with this type of surgery is identification of the lesion and confirmation of its removal by the pathologist, which may be difficult. Ghelman and associates26 have described a method for localizing an osteoid osteoma intraoperatively using a scintillation probe. This technique may simplify the localization of the lesion at the time of surgery. Patients whose lesions are not completely excised will probably continue to have the same pain and will probably require a second operation.50 The authors have observed that the loss of motion so characteristic of this lesion at the elbow resolves with removal of the nidus. Hence, capsular release is not necessary as an adjunctive procedure.60

Osteochondroma

Osteochondroma is probably the most common benign bone tumor, but it is not very commonly encountered in the elbow. The incidence may be somewhat higher than that reflected in our surgical experience, however, because many osteochondromas in other locations are asymptomatic and presumably may also be in the region of the elbow. The osteochondroma is not inherently painful but causes symptoms by pressure on adjacent structures. The tumor may be found in a patient of any age, but it usually stops growing when skeletal maturity is reached. An osteochondroma may arise from the surface of any bone but most commonly does so in the metaphyseal region of long bones (Fig. 82-5). The tumor tends to project away from the joint along the direction of attached muscles. The tumor may be pedunculated on a stalk or may be sessile and have a broad base (Fig. 82-6). The tumor is covered by a cartilage cap, which, if it becomes markedly thickened, suggests the possibility of sarcomatous transformation. If it is more than 1 cm thick, the risk of secondary chondrosarcoma is relatively high. In children, the cartilage cap is normally thicker than in adults. Probably fewer than 1% of osteochondromas ever become malignant.29

FIGURE 82-5 Osteochondroma in a 23-year-old woman. Radial shaft with cortical and medullary bone extending into tumor.

FIGURE 82-6 Osteochondroma of the distal humerus in a 41-year-old man. Note the soft tissue reaction.

Osteochondromas in the region of the elbow may cause mechanical difficulties; specifically, interference with the motion of the elbow joint. In addition, the cartilage cap may impinge on important neurovascular structures. If there are symptoms or mechanical or cosmetic difficulties, complete excision of the osteochondroma, together with the overlying cartilage cap, is performed. Excision commonly involves the use of an osteotome to shave the lesion level with the underlying cortical bone. Such simple excision generally results in cure, although local recurrence may occasionally be noted, indicating that part of the cartilaginous cap was left behind. If the cap is thicker than 1 cm in an adult, the lesion must be carefully studied histologically to exclude the possibility of a sarcoma.

Giant Cell Tumor

Giant cell tumors nearly always occur in the epiphyseal region and may extend to the articular surface of the bone. Campanacci and coworkers10 have attempted to grade giant cell tumors according to radiographic criteria; thus, grade 1 lesions are radiographically indolent, and grade 3 tumors are radiographically aggressive. Unfortunately, the majority of giant cell tumors are probably what Campanacci and colleagues refer to as grade 2, in which the radiographic appearance is aggressive but the tumor has not yet broken through cortical bone. Radiographic grading may be important in helping the surgeon decide on the appropriate treatment.

Grossly, the tumor consists of a red, soft tissue that typically extends up the subchondral bone at the articular surface. Microscopically, a giant cell tumor shows a combination of giant cells and mononuclear cells, with a more or less uniform distribution of the giant cells. Giant cell tumors that appear to be more aggressive histologically do not necessarily behave more aggressively clinically.17

The extent of surgery required to eradicate giant cell tumors is somewhat controversial. In the region of the elbow, particularly difficult problems may be encountered. The distal end of the humerus does not lend itself well to surgical excision by curettage unless the lesion is radiographically a grade 1 lesion. Total excision of the distal end of the humerus, although it would probably be curative and prevent local recurrence, creates a very serious problem for the reconstructive surgeon. Allograft replacement might be considered in this setting, but the decision about the method of treatment is often exceedingly difficult. Excision by curettage in other locations results in a local recurrence rate of approximately 25%. It is probably reasonable to accept this risk and to try curettage for the first treatment because the alternative of resection of the distal end of the humerus is so drastic (Fig. 82-7). However, if the tumor has already broken through the cortex into the surrounding soft structures, curettage is unlikely to be effective. For tumors of the proximal end of the ulna, curettage might be more reasonable because there is more bone to work with; hence, a larger margin of normal bone can be included in the resected specimen, whether resection is done by curettage or actual excision. Whenever possible, the treatment of choice is to pack the tumor cavity with methylmethacrylate (Fig. 82-8). This method of reconstruction has, in other locations, proved to be effective. If the proximal radial head is involved with a reasonably small tumor, it is probably best treated with simple excision.28,32

Aneurysmal Bone Cyst

In the Mayo Clinic’s experience with 134 aneurysmal bone cysts unrelated to pre-existing disease, 43% occurred in men. In contrast to the age of predilection for giant cell tumors, 78% of the patients were younger than 20 years of age. Only eight examples of aneurysmal bone cysts were found in the region of the elbow. Pain and swelling are the most common features.14

Radiographically, the diseased area is sometimes confusingly like that of a malignant tumor, but the zone of rarefaction is usually well circumscribed, eccentric, and associated with an obvious soft tissue extension of the process (Fig. 82-9). Classically, the soft tissue extension is produced by bulging of the periosteum and a resultant layer of radiographically visible new bone that delimits the periphery of the tumor. Fusiform expansion may be produced, especially when small bones such as a fibula or a rib are affected. The lesion is usually metaphyseal in location.6,18

Pathologically, an aneurysmal bone cyst contains anastomosing cavernous spaces that usually constitute the bulk of the lesion. The spaces are usually filled with unclotted blood, which may well up into, but does not spurt from, the tumor when it is unroofed. The most important factor to recognize histologically is the benign quality of the constituent cells.16,46 Telangiectatic osteosarcomamay simulate aneurysmal bone cyst when viewed at low magnification.

OTHER BENIGN BONE TUMORS AND TUMOR SIMULATORS

Benign tumors of bone at the elbow other than those previously discussed may rarely be encountered (Fig. 82-10). In addition, a number of lesions may occur in any bone and may simulate or mimic a primary bone tumor (Figs. 82-11 through 82-13). Benign cartilage tumors are very rare at the elbow; nevertheless, they do occasionally occur (Fig. 82-14).

MALIGNANT BONE TUMORS

Lymphoma

Currently, the term malignant lymphoma is used for those small round cell tumors of bone that previously were referred to as reticulum cell sarcoma.42 Lymphoma tends to occur in middle-aged or elderly adults; young persons are uncommonly affected. Patients with lymphoma generally present with pain and perhaps swelling in the region of the lesion. The tumor may arise primarily in any bone, including bones in the region of the elbow (Fig. 82-15).

The radiographic features of lymphoma are nonspecific (Fig. 82-16). There is usually a diffuse, destructive, mottled appearance with indistinct margins. Variable degrees of sclerosis may be present in the lesion; the cortical bone is usually eroded, and the tumor may extend into the adjacent soft tissues. Periosteal new bone formation usually is not a prominent feature.

Grossly, lymphoma tissue is usually gray or white and very soft. Microscopically, malignant lymphomas fit into the group of small round cell tumors. Under low power, the tumor shows a permeative pattern. The infiltrate tends to fill up the marrow cavity without destroying medullary bone. When a diagnosis of lymphoma in bone is made, it is important to stage the disease process. If the disease is localized to one site, the prognosis is excellent.40 About a fourth of patients will have multiple bones involved. Even these patients do well. However, if there are other sites, such as liver, spleen, or lymph nodes, the survival rate decreases dramatically.

There is no clear-cut or obvious advantage to the use of adjunctive chemotherapy at the time of initial treatment if only a solitary lesion is present.49

In general, lymphoma presenting primarily in bone has a long-term survival of about 60%.7 However, no figures are available for the occurrence of lymphoma of bone specifically at the elbow.

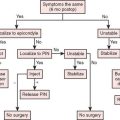

Ewing’s Sarcoma

The usual radiographic appearance of Ewing’s sarcoma is that of a mottled or moth-eaten destructive lesion that may contain both lytic and blastic areas (Fig. 82-17). Although not pathognomonic, there is frequently periosteal reactive new bone, which may form layers, forming the “onion skin” appearance that is reported to be typical of this disease. The radiographic appearance combined with the presence of fever and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate may lead to the erroneous diagnosis of osteomyelitis.2

Grossly, Ewing’s sarcoma may be very soft or even semiliquid; indeed, the appearance may simulate the purulence of infection. Microscopically, Ewing’s sarcoma is very cellular, composed of small round cells that are remarkably similar to one another. Periosteal new bone formation, if present, may complicate the histologic interpretation.47

Treatment of Ewing’s sarcoma of bone in the region of the elbow is similar to that for other sites. The local lesion is generally treated with radiation therapy, and systemic combination chemotherapy is generally used in an attempt to prevent micrometastases. Although there is a growing trend toward considering a larger role for surgery in the treatment of the primary lesion, there is little enthusiasm for resecting malignant tumors in the region of the elbow because it is difficult to achieve adequate margins in this region without damaging important normal structures.44 Even if an adequate resection could be achieved, satisfactory reconstruction would be difficult or impossible. This is particularly true when one deals with children with open physes. Thetreatment for Ewing’s sarcoma is the same as that for lymphoma in the region of the elbow.5,31 A major side effect is soft tissue fibrosis causing a stiff joint.

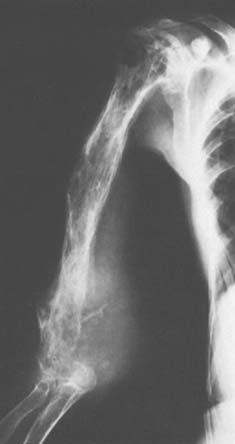

Osteosarcoma

Osteosarcoma is the most common bone malignancy except for myeloma. Radiographically, osteosarcoma usually appears to be aggressive, with evidence of cortical destruction and reactive periosteal new bone for-mation. In the distal humerus, the classic “sunburst” appearance may be evident. The precise extent of the lesion may not be apparent on plain radiographs (Fig. 82-18). The tumor can usually be more accurately assessed with a technetium or gallium bone scan. Other studies, such as CT, may be used to help determine the extent of soft tissue involvement if it is present. Magnetic resonance imaging may be helpful in further defining both the extent of soft tissue involvement and the extent of intramedullary involvement.

FIGURE 82-18 Grade 4 osteosarcoma of the distal end of the humerus in a patient with Paget’s disease of the entire bone.

About one half of these tumors are predominantly fibrous or cartilaginous, and the remainder are predominantly bone forming. Because any one of these three types of differentiation may predominate, the lesions may be subtyped into fibroblastic, chondroblastic, or osteoblastic osteosarcoma. This subclassification may be important because the osteoblastic subtype appears to have a worse prognosis than the other two subtypes.9,15,19,35,56–58

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma can also show areas of matrix production.20 Yet, only one of the 83 tumors listed as malignant fibrous histiocytoma in the Mayo Clinic files occurred in the elbow region. From a practical standpoint, the clinical management of this malignancy is essentially identical with that of osteosarcoma (Fig. 82-19). In the author’s own experience, 8% to 10% of patients with newly diagnosed osteosarcoma are foundto have metastatic disease, either by plain radiography or CT.53

METASTATIC TUMORS

There is no particular predilection for metastatic disease to involve the elbow. Yet extensive destruction is observed on occasion from several tumor types. Treatment is most commonly joint replacement (Fig. 82-20). In the editor’s experience, 18 of 20 conditions treated with joint replacement were metastatic. Patients do well in general with this palliative treatment. Complications relate to nerve dysfunction and stiffness.3

SOFT TISSUE TUMORS

Many benign soft tissue tumors are commonly encountered; however, because some soft tissue sarcomas may grow very slowly, both the patient and the physician may be misled into thinking that a soft tissue mass is benign. When this happens, a definitive diagnosis may be delayed, sometimes for years. When the patient does seek medical attention, it is common for the physician to perform a biopsy procedure that may jeopardize subsequent surgical care. As with bone tumors, proper placement of the biopsy incision is critical, and any subsequent resection surgery for malignant tumors demands that the biopsy site be included in the resected specimen. If the biopsy incision is not well placed, inclusion of the site at surgery may be difficult or impossible to achieve. If the mass is small and is situated in a favorable location, it is far preferable to perform an excisional biopsy, leaving a margin of normal tissue on all aspects of the suspected lesion. If an incisional biopsy is performed, sufficient tissue must be removed to allow adequate representative sampling of the tumor so that the pathologist can arrive at the correct diagnosis. Perhaps no other factor is as important in the management of patients with soft tissue tumors as the proper performance of the biopsy procedure.

BENIGN SOFT TISSUE TUMORS

Lipoma

Most lipomas are small, asymptomatic, and relatively dormant in that they seem to remain approximately the same size. Occasionally, however, the tumor may grow and become symptomatic. If there is trauma to the area, necrosis may develop within the lipoma, and this is usually symptomatic. Most lipomas consist almost entirely of adipose tissue; however, there may be increased vascularity, in which case the lesion is referred to as angiolipoma.21

Surgical excision should be considered for lipomas that increase in size, are symptomatic or cosmetically undesirable, or interfere with function and in situations when the diagnosis is not certain (Fig. 82-21). For most such tumors, a simple marginal excision is all that is indicated. The vulnerability of the neurovascular structures is of particular concern for lipoma of the antecubital space. When a lipoma is located within the belly of a muscle, it may be necessary to sacrifice some normal muscle tissue on all aspects to minimize the risk of local recurrence. At the elbow, this can cause permanent stiffness.

Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis

In the past, pigmented villonodular synovitis had various names, including xanthoma, xanthogranuloma, giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath, and myeloplaxoma. This disease probably belongs in the middle of the spectrum of diseases, within the general category of fibrous histiocytoma. It involves the synovium, bursae, or tendon sheaths. The knee is the most common site of involvement. In the authors’ experience, only two cases occurred in the elbow joint.43 This is not surprising, because Pimpalnerkar43 reports that only 18 cases have been cited in the literature through 1998.

Clinically, there are two forms of the disease: nodular and diffuse. The nodular or localized form is probably most frequently encountered in the small joints of the fingers, whereas the diffuse form is most commonly found in the knee joint. At the elbow, swelling, with a suggestion of increased thickening of the synovium, may be present, but motion loss is always present. Radiographs may reveal cystic erosions on either side of the joint (Fig. 82-22). When erosions are found and there is no loss of joint space and no demineralization of the surrounding bone, the diagnosis should be suspected. In most cases of pigmented villonodular synovitis, however, there is no bony erosion but there is evidence of lobular swelling of the soft tissues.4

In the nodular form, the nodule may be simply excised with the expectation that a cure will be achieved in most cases. However, the results of treatment of the diffuse form are likely to be followed by local recurrence, which is more frequent when there is evidence of bony erosion. Even multiple synovectomies have not always been curative; because of this, various alternative treatments have been attempted. Radiation therapy has been used, but there is no convincing evidence that such treatment will actually eliminate the disease and prevent local recurrences. High doses of radiation are avoided at the elbow joint. Synovectomy is the treatment of choice, but the incidence of recurrence is at least 33% with open procedure.43 This may be less with arthroscopic procedures (Fig. 82-23). If synovectomy leads to symptomatic local recurrence, arthrodesis is considered in most joints. At the elbow, however, because this joint does poorly with an arthrodesis, replacement arthroplasty would appear to be the treatment of choice.

Synovial Chondromatosis

Chondromatosis is a benign, tumorous, multifocal, chondromatous, or chondro-osseous metaplastic proliferation involving the subsynovial connective tissue of joints, tendon sheaths, or bursae (see Chapter 83). The process can involve any joint. The average age of the patients is about 40 years; men are affected more often than women. Symptoms include pain and limited motion. The duration of symptoms may be long or relatively short before diagnosis is made. In the Mayo Clinic series, only two thirds of the radiographs showed radiopaque masses (Fig. 82-24).37 Diagnosis is difficult because the radiograph may not reveal ossified bodies even when they are present.

FIGURE 82-24 Synovial chondromatosis of the elbow. Note that a small mineralized focus is evident in the antecubital fossa.

The treatment of osteochondromatosis consists of removing any loose osteochondromatous bodies and the involved synovium from which they arise. In general, complete synovectomy is necessary and today is done arthroscopically. The condition may recur because nests of synovium may be left behind. If this happens, a second procedure, maybe even an arthrotomy, is necessary. Long-standing synovial osteochondromatosis creates secondary osteoarthritis (see Chapters 83 and 85).

Myositis Ossifications (Heterotopic or Ectopic Ossification)

Heterotopic ossification, often erroneously called myositis ossificans, may occur near the elbow, either in muscle or in other soft tissue. In its early, or “florid,” stage, there may be such pronounced cellular activity that it may be mistaken for sarcoma.1 The relative rarity of this disease has delayed understanding of the peculiar tissue reaction associated with it. The topic has been thoroughly reviewed in Chapter 31.

A similar non-neoplastic benign, reactive process may occur in the deeper portions of the skin. The poorly defined small mass that is found may also show prominent mitotic activity. The lesion is called proliferative fasciitis and has been mistaken for entities such as liposarcoma or fibrosarcoma.11 The rapidly proliferating cells again do not show true anaplasia. Another related entity is proliferative myositis.25 In this condition, there is a tumefactive, intramuscular proliferation of benign fibroblastic cells, but no discernible osseous metaplasia. Mitotic activity may be pronounced, making it possible to mistake this lesion for a malignant tumor.

MALIGNANT SOFT TISSUE TUMORS

Synovial Sarcoma

Synovial sarcoma, or synovioma, is a malignant soft tissue tumor that usually arises in the extremities or limb girdles; about 70% of lesions involve the lower extremity, most commonly the thigh, but this tumor does occur in the region of the elbow. In the Mayo Clinic experience, only the tumors of about 20% of patients had suggestive evidence of origin from anatomic synovium.61 This tumor can be found in patients of any age, but young or middle-aged adults seem to be most commonly affected.

Symptoms may be present for many years before diagnosis. In the Mayo Clinic experience, the average duration of symptoms before diagnosis was 2½ years. The radiographic examination may be particularly helpful because about a third of patients with synovial sarcoma show evidence of calcification. When calcification is found in a soft tissue tumor, synovial sarcoma should be included in the differential diagnosis. This tumor can invade the bone on a rare occasion.39

Close cooperation between the pathologist and the surgeon is essential if the diagnosis is to be made at surgery. Local excision of the tumor generally results in a local recurrence; with local recurrence, the prognosis for survival is lessened. In the Mayo Clinic experience, the overall 5-year survival rate was 23%, with a median survival time of 39 months.59 However, for patients treated after 1960, the 5-year survival rate has been 55% and the 10-year rate has been 38%. Patients who had the best prognosis were those treated with wide excision or radical surgery. Today, the authors usually combine radiation therapy and surgery; with this approach local recurrence occurs in only about 5% of cases. We do not routinely employ lymphadenectomy unless the regional nodes are clinically involved.

Liposarcoma

The extent of treatment depends, at least in part, on both the size and the grade of the tumor. Lesions that are grade 1 or grade 2 probably can be safely excised with a margin of normal tissue on all aspects, but this can be very difficult at the elbow. If the lesion recurs, it can probably be excised without the need for radical surgery. However, the higher grade lesion should probably be treated with wide resection and perhaps with radical resection unless the tumor can be totally and widely removed without sacrifice of limb function. This is difficult to do with tumors in the region of the elbow, and amputation may be necessary. As with other soft tissue sarcomas, the authors usually combine radiation therapy and surgery. In the Mayo Clinic experience, more than 50% of all patients treated for liposarcoma may expect to survive for 5 years and be free from evidence of disease progression.45

Malignant Fibrous Histiocytoma

There is no one universally acceptable treatment for this lesion. Relatively small tumors may be excised with a margin of normal tissue on all aspects. Larger lesions or those that are histologically higher grade require a more aggressive approach. In this situation, the authors now favor a course of preoperative radiation therapy using approximately 5000 rad, followed after several weeks by excision of the lesion with a margin of normal tissue on all aspects. Adjunctive chemotherapy has not been helpful in our experience.

Epithelioid Sarcoma

Epithelioid sarcoma is a rare, slowly growing malignant tumor that usually begins in the superficial tissues of the hand or forearm and may occur at the elbow. The tumor is made up of small, poorly defined tumor nodules composed of epithelioid cells or histiocytic aggregates. Sometimes, central necrosis in these aggregates of cells suggests that the disease is a granulomatous infection. There is often a delay in recognition of the malignant nature of the disease, and the long-term prognosis for life is poor. Rarely, the tumor erodes into underlying bones (Figs. 82-25 and 82-26). Lymphatic or hematogenous metastasis is common, especially in the later stages of this disease.

1 Ackerman L.N. Extra-osseous localized non-neoplastic bone and cartilage formation (so-called myositis ossificans): Clinical and pathologic confusion with malignant neoplasms. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1958;40A:279.

2 Angervall L., Enzinger F.M. Extraskeletal neoplasm resembling Ewing’s sarcoma. Cancer. 1975;36:240.

3 Athwal G.S., Chin P.Y., Adams R.A., Morrey B.F. Coonrad-Morrey total elbow arthroplasty for tumours of the distal humerus and elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2005;87B:1369.

4 Atmore W.G., Dahlin D.C., Ghormley R.K. Pigmented villonodular synovitis: A clinical and pathologic study. Minn. Med. 1956;39:196.

5 Bacci G., Picci P., Gitelis S., Borghi A., Campanacci M. The treatment of localized Ewing’s sarcoma: The experience at the Istituto Ortopedico Rizzoli in 163 cases treated with and without adjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer. 1982;49:1561.

6 Bonaledarpeun A., Levy W.M., Aegerter E. Primary and secondary aneurysmal bone cyst: A radiologic study of 75 cases. Radiology. 1978;126:75.

7 Boston H.C.Jr., Dahlin D.C., Ivins J.C., Cupps R.E. Malignant lymphomas (so-called reticulum cell sarcoma) of bone. Cancer. 1974;34:1131.

8 Brabants K., Geens S., van Damme B. Subperiosteal juxta-articular osteoid osteoma. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1986;68:320.

9 Campanacci M., Cervelatti G. Osteosarcoma: A review of 345 cases. Ital. J. Orthop. Traumatol. 1975;1:5.

10 Campanacci M., Giunti A., Olmi R. Giant cell tumors of bone: A study of 209 cases with long-term follow-up in 130. Ital. J. Orthop. Traumatol. 1975;1:249.

11 Chung E.B., Enzinger F.M. Proliferative fasciitis. Cancer. 1975;36:1450.

12 Corbett J.M., Wilde A.H., McCormick L.J., Evarts C.M. Intra-articular osteoid osteoma, a diagnostic problem. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1974;98:225.

13 Cronemeyer R., Kirchmer N.A., Desmet A.A., Neff J.R. Intra-articular osteoid osteoma of the humerus simulating synovitis of the elbow: A case report. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1981;63A:1172.

14 Dahlin D.C. Bone Tumors: General Aspects and Data on 6221 Cases. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas, 1978;445.

15 Dahlin D.C. Pathology of osteosarcoma. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1975;111:23.

16 Dahlin D.C., Besse B.E.Jr., Pugh D.G., Ghormley R.K. Aneurysmal bone cysts. Radiology. 1955;64:56.

17 Dahlin D.C., Cupps R.E., Johnson E.W.Jr. Giant cell tumor: A study of 195 cases. Cancer. 1970;25:1061.

18 Dahlin D.C., McLeod R.A. Aneurysmal bone cyst and other non-neoplastic conditions. Skeletal Radiol. 1982;8:243.

19 Dahlin D.C., Unni K.K. Osteosarcoma of bone and its important recognizable varieties. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1977;1:61.

20 Dahlin D.C., Unni K.K., Matsuno T. Malignant (fibrous) histiocytoma of bone—fact or fancy? Cancer. 1977;39:1508.

21 Dionne G.P., Seemayer T.A. Infiltrating lipomas and angiolipomas revisited. Cancer. 1974;33:732.

22 Edeiken J., Hodes P.J.. 2nd ed.. Roentgen Diagnosis of Diseases of Bone, Vols. 1 and 2. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, 1973.

23 Enneking W.F.. Musculoskeletal Tumor Surgery, Vol. 1. Churchill Livingstone, New York, 1983.

24 Enneking W.F., Spanier S.S., Goodman M.A. A system for the surgical staging of musculoskeletal sarcoma. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1980;153:106.

25 Enzinger F.M., Dulcey F. Proliferative myositis: Report of thirty-three cases. Cancer. 1967;20:2213.

26 Ghelman B., Francesca M., Thompson F.M., William D., Arnold W.D. Intra-operative radioactive localization of an osteoid osteoma: Case report. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1981;63A:826.

27 Gil-Albarova J., Amillo S. Osteoblastoma causing rigidity of the elbow: A case report. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1991;62:602.

28 Goldenberg R.R., Campbell C.J., Bonfiglio M. Giant cell tumor of bone: An analysis of. 218 cases. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1970;52A:621.

29 Harsha W.N. The natural history of osteocartilaginous exostoses (osteochondroma). Am. Surg. 1954;20:65.

30 Jaffe H.L., Lichtenstein L. Osteoid-osteoma: Further experience with this benign tumor of bone; with special reference to cases showing the lesion in relation to shaft cortices and commonly misclassified as instances of sclerosing non-suppurative osteomyelitis or cortical-bone abscess. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1940;22:645.

31 Johnson R.E., Pomeroy T.C. Evaluation of therapeutic results in Ewing’s sarcoma. A.J.R. 1975;123:583.

32 Larsson S.E., Lorentzon R., Boquist L. Giant-cell tumor of bone: A demographic, clinical, and histopathological study of all cases recorded in the Swedish Cancer Registry for the years. 1958 through 1968. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1975;57A:167.

33 Lenoble E., Sergent A., Goutallier D. Preoperative, intraoperative, and immediate postoperative skeletal scintigraphy to locate and facilitate excision of an osteoid osteoma of the coronoid process. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1994;Sept./Oct.:323.

34 Marcove R.C., Freiberger R.H. Osteoid osteoma of the elbow: A diagnostic problem. Report of four cases. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1966;48A:1185.

35 Matsuno T., Unni K.K., McLeod R.A., Dahlin D.C. Telangiectatic osteogenic sarcoma. Cancer. 1976;38:2538.

36 Moser R.P.Jr., Kransdorf M.J., Brower A.C., Hudson T., Aoki J., Berrey B.H., Sweet D.E. Osteoid osteoma of the elbow: A review of six cases. Skeletal Radiol. 1990;19:181.

37 Murphy F.P., Dahlin D.C., Sullivan C.R. Articular synovial chondromatosis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1962;44A:77.

38 Norman A., Dorfman H.D. Osteoid osteoma inducing pronounced overgrowth and deformity of bone. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1975;110:223.

39 O’Donnell P., Diss T.C., Whelan J., Flanagan A.M. Synovial sarcoma with radiological appearances of primitive neuroectodermal tumour-Ewing sarcoma: Differentiation by molecular genetic studies. Skeletal Radiol. 2006;35:233.

40 Ostrowski M.L., Unni K.K., Banks P.M., Shives T.C., Evans R.G., O’Connell M.J., Taylor W.F. Malignant lymphoma of bone. Cancer. 1986;58:2646.

41 Otsuka N.Y., Hastings D.E., Fornasier V.L. Osteoid osteoma of the elbow: A report of six cases. J. Hand Surg. 1992;17:458.

42 Parker F.Jr., Jackson H.Jr. Primary reticulum cell sarcoma of bone. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet.. 1939;68:45.

43 Pimpalnerkar A., Barton E., Sibly T.F. Pigmented villonodular synovitis of the elbow. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7:71.

44 Pritchard D.J., Dahlin D.C., Dauphine R.T., Taylor W.E., Beabout J.W. Ewing’s sarcoma: A clinicopathological and statistical analysis of patients surviving five years or longer. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1975;57A:10.

45 Reszel P.A., Soule E.H., Coventry M.B. Liposarcoma of the extremities and limb girdles: A study of two hundred twenty-two cases. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1966;48A:229.

46 Sanerkin N.G., Mott M.G., Roylance J. An unusual intraosseous lesion with fibroblastic, osteoclastic, osteoblastic, aneurysmal, and fibromyxoid elements: “Solid” variant of aneurysmal bone cyst. Cancer. 1983;51:2278.

47 Schajowicz F. Tumors and Tumor-like Lesions of Bones and Joints. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1981;581.

48 Schajowicz F., Lemos C. Osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma: Closely related entities of osteoblastic derivation. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1970;41:272.

49 Schwartz H.S., Unni K.K., Pritchard D.J. Pigmented villonodular synovitis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1989;247:243.

50 Shoji H., Miller T.R. Primary reticulum cell sarcoma of bone: Significance of clinical features upon the prognosis. Cancer. 1971;28:1234.

51 Sim F.H., Dahlin D.C., Beabout J.W. Osteoid osteoma: Diagnostic problems. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1975;57A:154.

52 Snarr J.W., Abell M.R., Martel W. Lymphofollicular synovitis with osteoid osteoma. Radiology. 1973;106:557.

53 Spanos P.K., Payne W.S., Ivins J.C., Pritchard D.J. Pulmonary resection for metastatic osteogenic sarcoma. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1976;58A:624.

54 Sperling J.W., Pritchard D.J., Morrey B.F. Total elbow arthroplasty following resection of tumors at the elbow. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1999;367:256.

55 Swee R.G., McLeod R.A., Beabout J.W. Osteoid osteoma: Detection, diagnosis, and localization. Radiology. 1979;130:117.

56 Taylor W.F., Ivins D.C., Edmonson J.H., Pritchard D.J. Trends and variability in survival from osteosarcoma. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1978;53:695.

57 Unni K.K., Dahlin D.C., Beabout J.W. Periosteal osteogenic sarcoma. Cancer. 1976;37:2476.

58 Unni K.K., Dahlin D.C., Beabout J.W., Ivins J.C. Parosteal osteogenic sarcoma. Cancer. 1976;37:2466.

59 Weatherby R.P., Dahlin D.C., Ivins J.C. Postradiation sarcoma of bone: Review of 78 Mayo Clinic cases. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1981;56:294.

60 Weber K., Morrey B.F. Osteoid osteoma of the elbow: A diagnostic challenge. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1999;81A:1111.

61 Wright P.H., Sim F.H., Soule E.H., Taylor W.F. Synovial sarcoma. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1982;64A:112.