Neoplasms in the region of the pituitary fossa

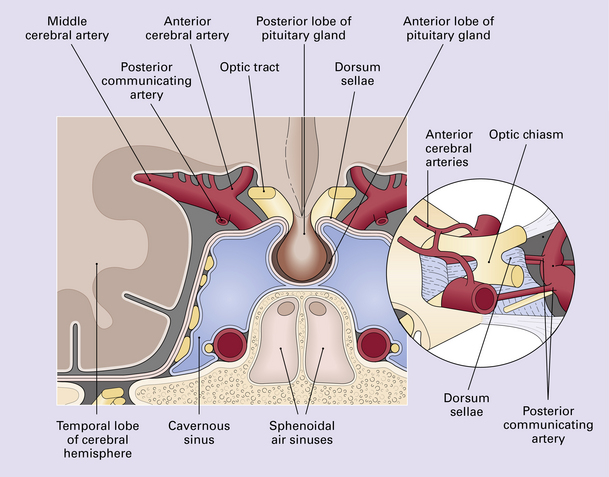

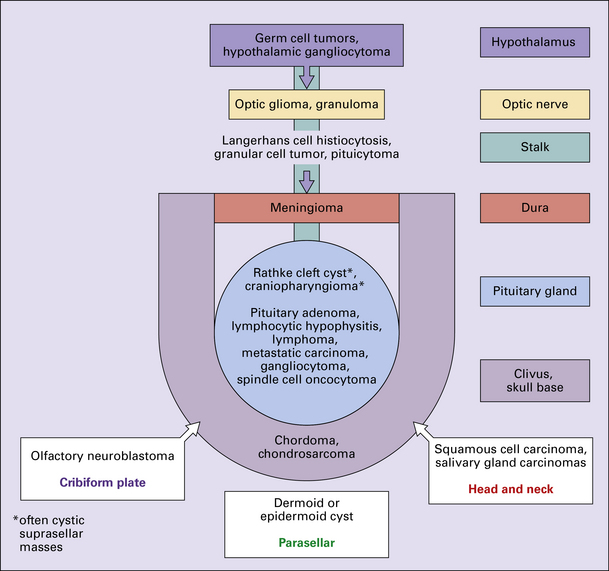

Neoplasms in the region of the pituitary fossa may arise in the pituitary gland itself, the sphenoid bone that surrounds the fossa, or the suprasellar region (Figs 44.1, 44.2). Structures in the suprasellar region and adjacent to the pituitary fossa include the hypothalamus, optic chiasm, nasal sinuses, and cavernous sinuses and their contents.

44.2 Schematic illustration of the types and sources of neoplasm that can affect the pituitary gland.

Common neoplasms in this region are:

Uncommon neoplasms in this region are:

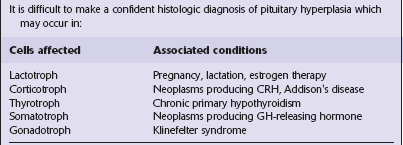

The pituitary gland weighs about 600 mg and consists mainly of the adenohypophysis (anterior lobe) and the neurohypophysis (posterior lobe) (Figs 44.3–44.6); the pars intermedia is poorly developed in man.

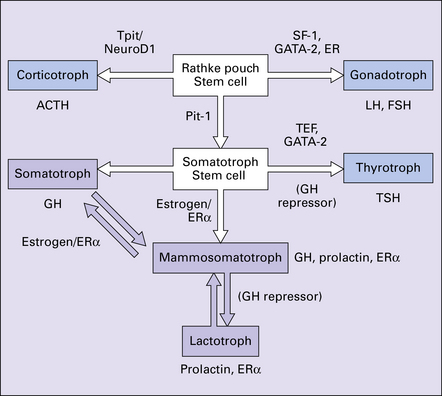

44.3 Hormonal cell type is mediated by transcription factors and estrogen receptors.

ERa, estrogen receptor alpha; FSH, follicle stimulating hormone; GATA-2, GATA binding protein 2; GH, growth hormone; (GH repressor), postulated growth hormone repressor; LH, luteinizing hormone; NeuroD1, neurogenic differentiation 1; Pit-1, pituitary transcription factor 1; SF1, steroidogenic factor 1; TEF, thyroid embryonic factor; TPit, pituitary restricted transcription factor; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone.

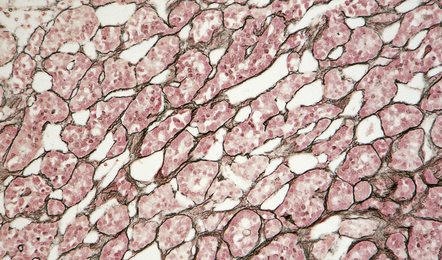

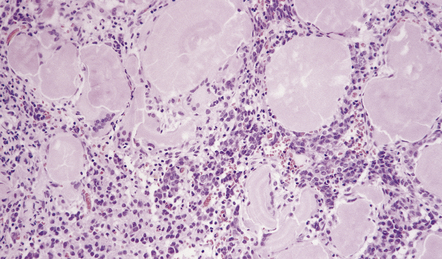

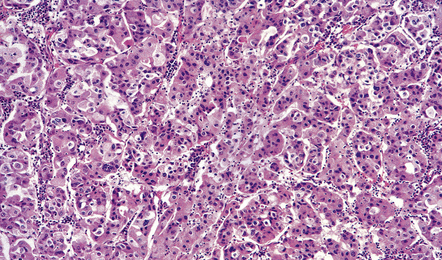

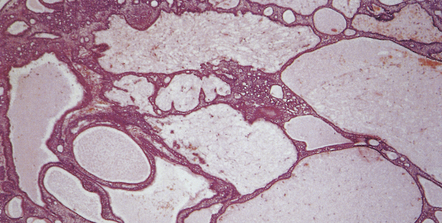

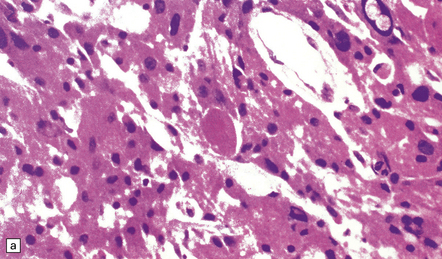

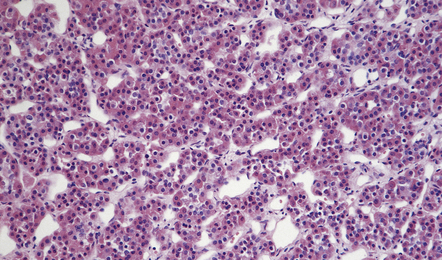

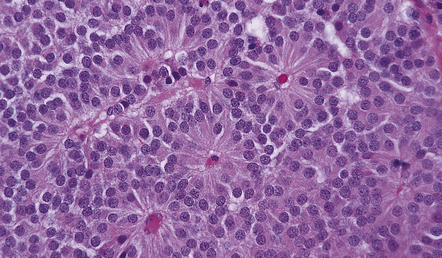

44.4 Normal adenohypophysis.

Nests of round or polyhedral cells, and an intervening network of vascular sinusoids are evident.

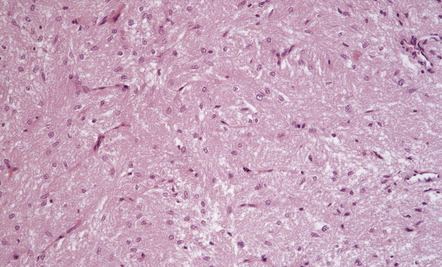

44.6 Normal neurohypophysis.

This consists of non-myelinated hypothalamohypophysial nerve fibers and a meshwork of capillaries adjacent to which the fibers terminate. Also present are specialized astrocytes (pituicytes).

PITUITARY ADENOMAS

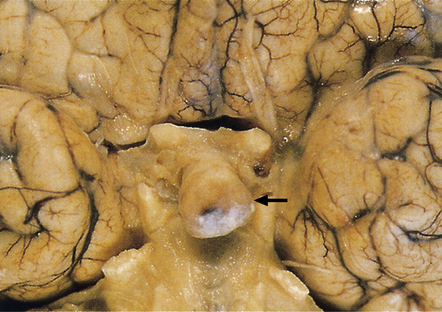

Pituitary adenomas are derived from secretory cells in the adenohypophysis. Some adenomas secrete peptides in an unregulated manner and may therefore produce abnormal endocrine effects in addition to causing mass effects in the region of the pituitary fossa (Fig. 44.7).

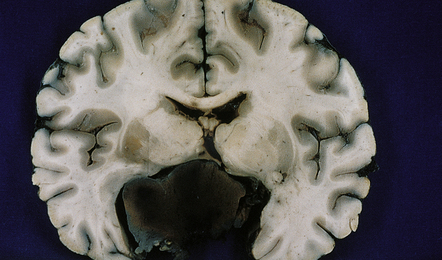

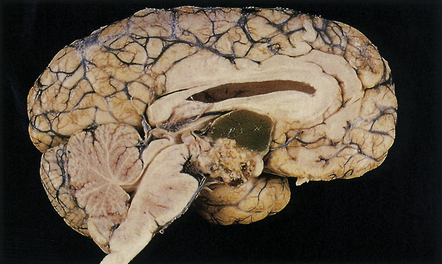

44.7 Pituitary adenoma.

Large, hemorrhagic pituitary adenoma producing distortion of surrounding structures.

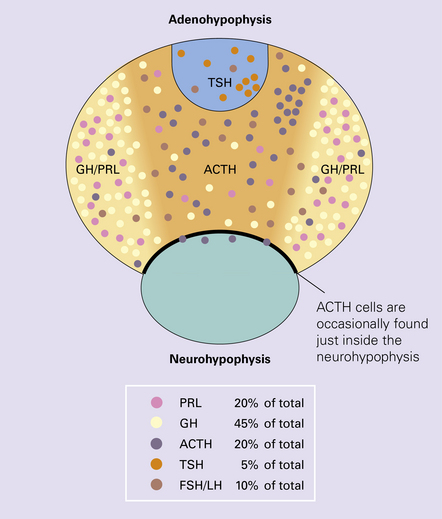

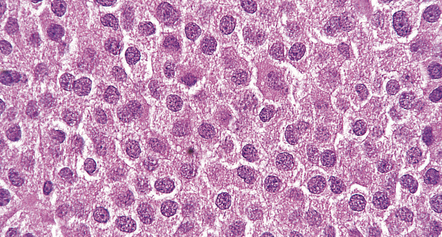

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

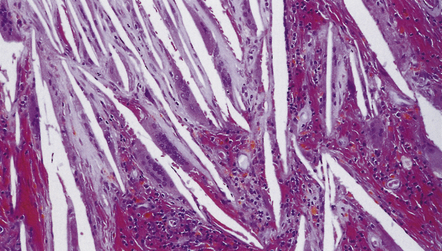

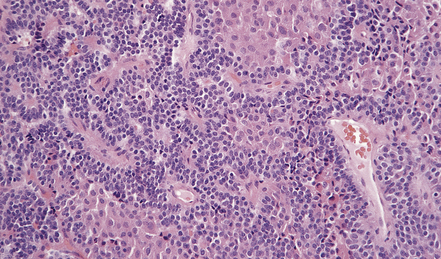

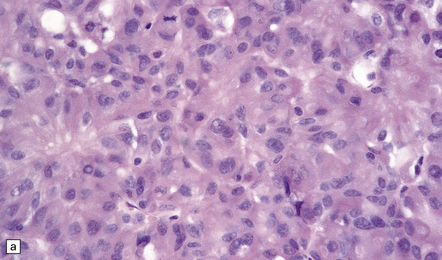

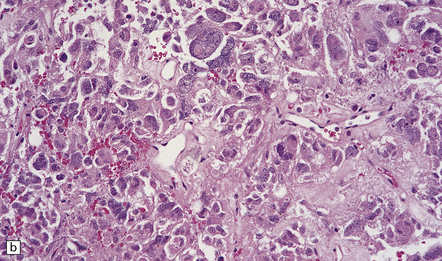

The histology of pituitary adenomas is varied (Table 44.1). Many adenomas consist of small, oval, or polyhedral cells. These may be arranged in monotonous sheets or show a variety of acinar, papillary, trabecular, or other patterns (Figs 44.9–44.11). The nuclei of neoplastic cells are generally round or oval and contain the stippled chromatin typical of neuroendocrine neoplasms. Tiny nucleoli may be evident. Cytologic pleomorphism and mitotic figures may be present, but do not necessarily signify aggressive biologic behavior (Fig. 44.12). Invasion of local structures (Fig. 44.13), particularly the dura, is not infrequent, even by adenomas with bland cytologic features.

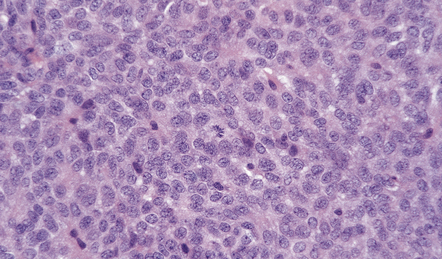

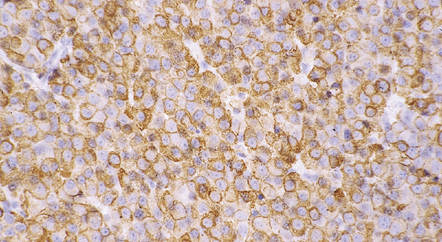

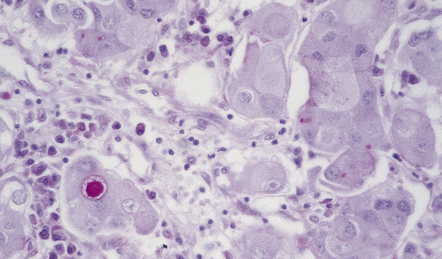

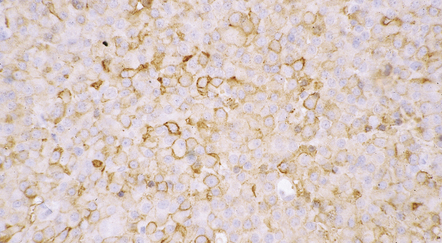

44.10 Pituitary adenoma.

A vascular network is seen between cells, some of which have formed pseudorosettes.

44.11 Pituitary adenoma composed of two populations of cells.

The larger cells were immunoreactive for GH.

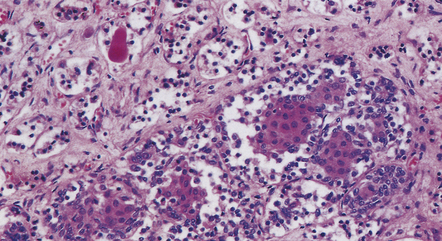

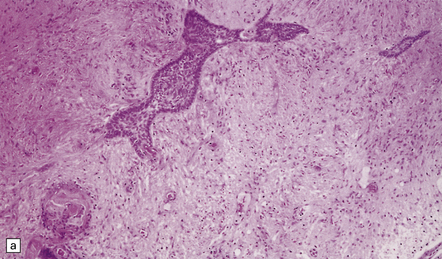

44.12 Pituitary adenoma. (a,b)

Cytologic pleomorphism and rare mitotic figures may be present and do not necessarily signify aggressive behavior.

44.13 Entrapped hypothalamic neurons at the invading edge of a suprasellar adenoma.

Adenomas containing neoplastic ganglion cells are recorded but are very rare.

Dystrophic calcification and eosinophilic (amyloid) bodies are strongly associated with prolactinomas (Fig. 44.14). Long-term treatment of prolactinomas with bromocriptine before surgical resection produces fibrosis.

Crooke’s hyaline change describes the development of a zone of glassy agranular cytoplasm around the nuclei of non-adenomatous corticotrophs in patients with elevated corticosteroid concentrations due to an ACTH-cell adenoma, a systemic ACTH-producing neoplasm, an adrenal neoplasm or exogenous corticosteroid administration (Fig. 44.15). This appearance results from a massive accumulation of keratin microfilaments.

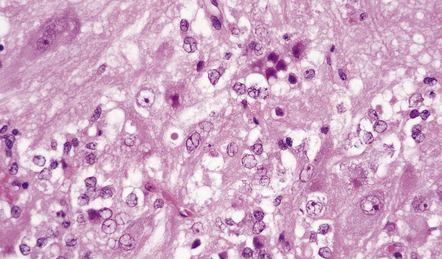

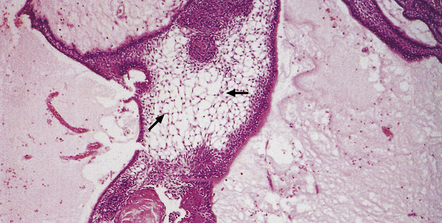

44.15 Crooke’s hyaline change.

Basophilic cytoplasm in corticotrophs is displaced by amorphous material. Perinuclear material has displaced the magenta granules in the corticotrophs to the periphery of the cytoplasm (arrows).

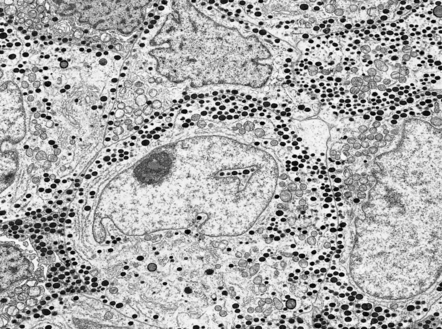

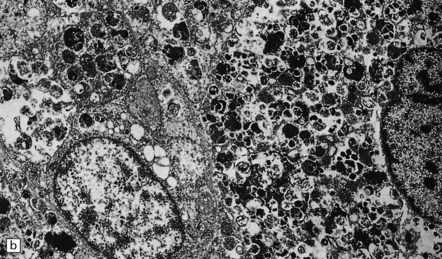

A small proportion of null-cell adenomas comprises oncocytomas (Fig. 44.16). The (arbitrary) ultrastructural criterion for a diagnosis of oncocytoma is that more than 10% of the cell volume must be occupied by mitochondria. ACTH-cell adenomas occasionally show oncocytic change.

44.16 Pituitary oncocytoma.

The uniform cells in this adenoma exhibit cytoplasmic granularity and eosinophilia. (Courtesy of Dr S van Duinen, Academisch Ziekenhuis, Leiden.)

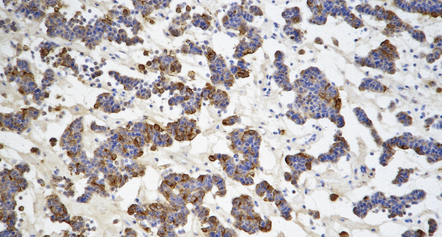

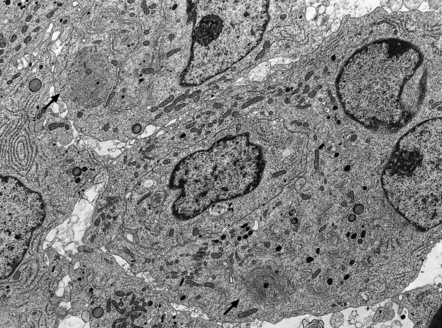

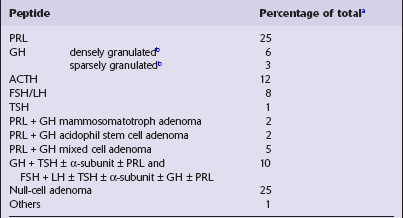

Immunohistochemistry to assess the production of peptide hormones (Figs 44.17–44.20, Table 44.2) is used with electron microscopy (Figs 44.21, 44.22) to classify pituitary adenomas. The various pituitary trichrome stains are useful for demonstrating normal adenohypophysis, but of limited value for distinguishing different types of adenoma. Immunolabeling of a hormone in adenoma cells does not necessarily signify that it is secreted in a physiologically active form. This is exemplified by the patchy and usually weak labeling of cells in some adenomas with FSH, LH, TSH or α subunit antibodies. Pituitary adenomas label with antibodies tosynaptophysin, chromogranin-A, and low molecular weight cytokeratins (Table 44.3).

Table 44.2

Pituitary adenomas classified by peptide production

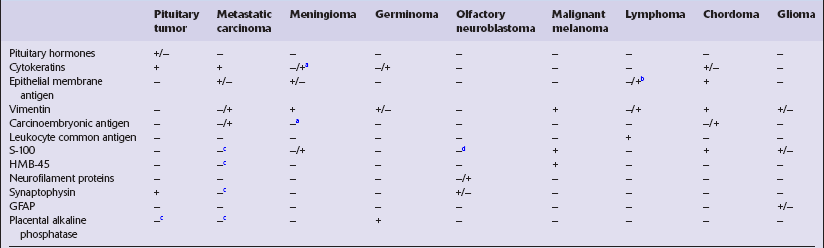

Table 44.3

Immunohistochemical profiles of neoplasms in the region of the pituitary fossa

+, nearly always immunoreactive;

+/−, majority of cases immunoreactive;

−/+, minority of cases immunoreactive.

aFocal immunoreactivity in secretory meningiomas.

bImmunoreactive in some anaplastic large cell lymphomas and lymphomas that show plasma cell differentiation.

cSome immunoreactive examples recognized.

dImmunoreactive sustentacular cells are present in some olfactory neuroblastomas.

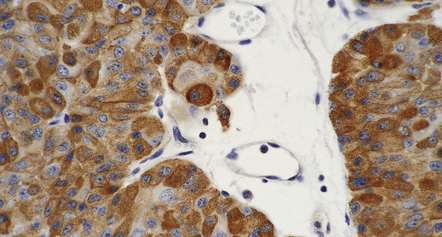

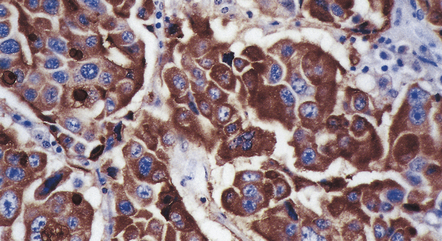

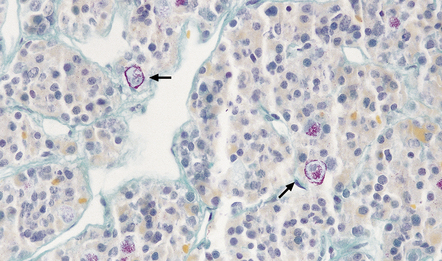

44.20 Mammosomatotroph adenoma.

Cells in the adenoma shown in Figure 44.16 label with a PRL antibody.

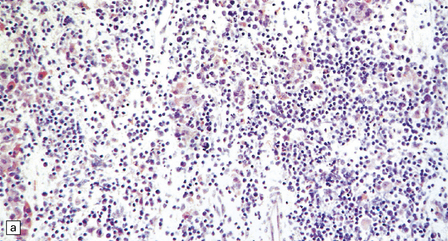

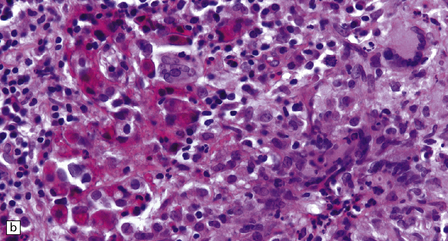

PITUITARY HYPERPLASIA

Pituitary hyperplasia (Table 44.4) may be nodular or diffuse. Nodular hyperplasia is characterized by enlarged cell nests and can be demonstrated in a reticulin preparation. Diffuse hyperplasia may not be obvious, requiring an appreciation of the uneven distribution of cells in the adenohypophysis (Fig. 44.28) and cell counts to make the diagnosis.

CRANIOPHARYNGIOMAS

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

An admixture of cystic and solid components is characteristic (Figs 44.29–44.31), and there is sometimes a smooth lobulated capsule. The solid tissue often contains foci of calcification and the cysts may contain a thick liquid that has been likened to machine oil. The papillary craniopharyngioma tends to be more circumscribed than the adamantinomatous type, and does not contain the calcification or oil-like cyst fluid of the adamantinomatous variant.

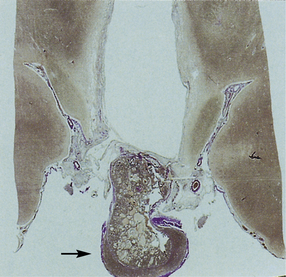

44.29 Craniopharyngioma.

This craniopharyngioma has solid and cystic components, and disrupts the diencephalon. Note the ‘machine oil’ nature of the cyst fluid.

44.31 Histology of the craniopharyngioma shown in Figure 44.30 (arrow).

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Features of the adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma (Figs 44.32–44.35) include:

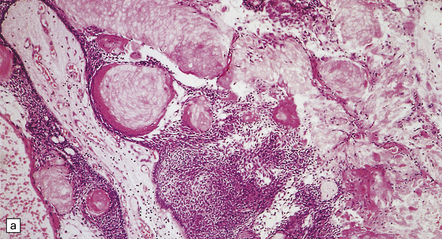

44.33 Adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma.

A loose matrix (stellate reticulum) is due to intercellular fluid accumulation (arrows).

44.34 Adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma.

(a,b) Sheets and nodules of keratinized ‘ghost’ cells are evident.

groups of squamous cells, often surrounded by a peripheral palisade of columnar cells

groups of squamous cells, often surrounded by a peripheral palisade of columnar cells

intercellular accumulations of fluid that separate the cells in some parts of the neoplasm

intercellular accumulations of fluid that separate the cells in some parts of the neoplasm

cohesive clusters or sheets of keratinized anuclear ‘ghost’ cells

cohesive clusters or sheets of keratinized anuclear ‘ghost’ cells

calcification, which may progress to metaplastic bone formation

calcification, which may progress to metaplastic bone formation

cholesterol clefts, which are often related to necrotic debris within the cysts.

cholesterol clefts, which are often related to necrotic debris within the cysts.

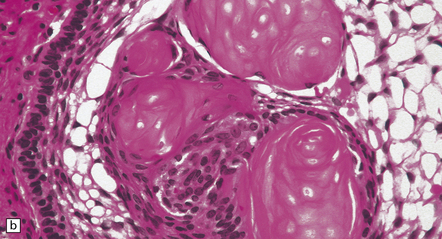

Papillary craniopharyngiomas (Fig. 44.36) consist of groups of squamous cells, which may form keratin pearls. Cysts are infrequent and an adamantinomatous pattern is absent. There are no nodules of keratinized ‘ghost’ cells and calcification is rare.

44.36 Papillary craniopharyngioma.

This variant lacks an adamantinomatous architecture and foci of degenerating keratinocytes.

The surrounding brain parenchyma is usually densely gliotic (Fig. 44.37) and may contain many Rosenthal fibers. Leakage of cyst contents may provoke an inflammatory reaction, which includes multinucleated giant cells (see Fig. 44.35).

RATHKE CLEFT CYST

Small cysts lined by cuboidal epithelium in the pars intermedia of the pituitary gland are remnants of Rathke’s pouch and can enlarge to produce a Rathke cleft cyst (Fig. 44.38). Small examples may be an incidental postmortem finding, but if the cysts are large enough they can produce endocrine or visual abnormalities.

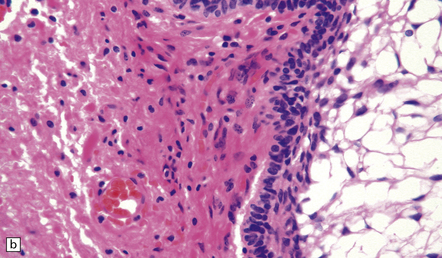

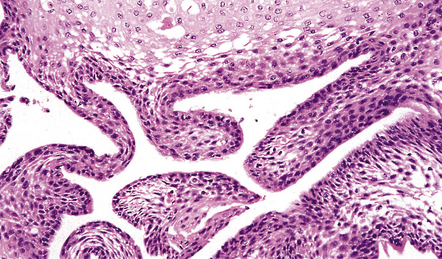

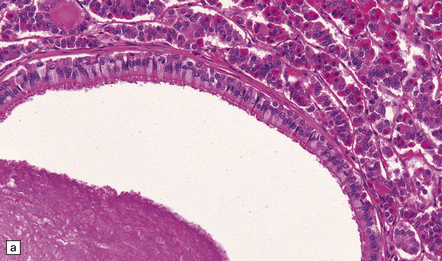

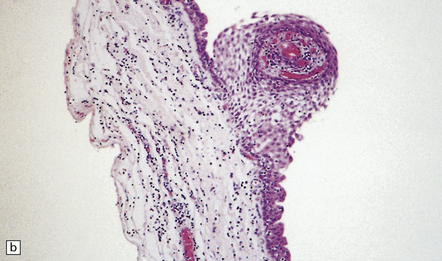

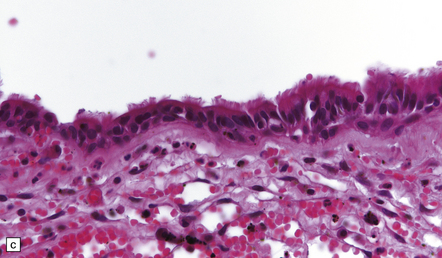

44.38 Rathke cleft cyst.

(a) Remnants of Rathke’s pouch in the adenohypophysis. (b) Rathke cleft cyst is lined by a simple columnar epithelium, but in this example also shows focal squamous metaplasia. (c) The epithelium is usually ciliated.

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Rathke cleft cysts usually have a thin wall and slightly cloudy mucinous contents. The cyst is lined by cuboidal or columnar epithelium, which may be ciliated (Fig. 44.38), and usually contains goblet cells. Peptide-containing cells may occasionally be found in the epithelium. The cuboidal/columnar epithelium sometimes incorporates a metaplastic stratified squamous epithelium. Microscopic cysts with a similar appearance are occasionally found in pituitary adenomas.

GRANULAR CELL NEOPLASM OF THE INFUNDIBULUM

MACROSCOPIC AND MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

Choristomas/tumorlets and granular cell neoplasms share cytologic features (Fig. 44.39). Their oval cells contain finely granular, eosinophilic, strongly PAS-positive cytoplasm. In larger neoplasms the cells may be arranged in fascicles. There is little nuclear pleomorphism and mitotic figures are not found. The cells are reactive for S-100 and CD68 with immunohistochemistry.

REFERENCES

Asa, S.L. Practical pituitary pathology: what does the pathologist need to know? Arch Pathol Lab Med.. 2008;132:1231–1240.

Asa, S.L., Tumors of the pituitary gland. Third series edn. Atlas of tumor pathology. Vol. 22, Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology 1998.

Burger, P.C., Scheithauer, B.W., Vogel, F.S. Region of the sella turcica. In: Surgical pathology of the nervous system and its coverings. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2002:437–490.

Ellison, D.W., Perry, A., Ronseblum, M., et al, Pituitary and sellar tumors. 8th ed,. Love, S., Louis, D.N., Ellison, D., eds. Greenfield’s neuropathology. Vol. 2. London: Hodder Arnold; 2008:2088–2116.

Lloyd, R.V., Kovacs, K., Young, W.F., Jr., et al. Tumors of the Pituitary. In: DeLellis R.A., Lloyd R.V., Heitz P.U., et al, eds. Pathology and genetics of tumours of endocrine organs. Lyon: IARC Press; 2004:9–45.

Calle-Rodrigue, R.D., Giannini, C., Scheithauer, B.W., et al. Prolactinomas in male and female patients: a comparative clinicopathologic study. Mayo Clin Proc.. 1998;73:1046–1052.

Horvath, E., Kovacs, K. Pathology of acromegaly. Neuroendocrinology.. 2006;83(3–4):161–165.

Horvath, E., Kovacs, K., Scheithauer, B.W. Pituitary hyperplasia. Pituitary.. 1999;1:169–179.

Horvath, E. Ultrastructural markers in the pathologic diagnosis of pituitary adenomas. Ultrastruct Pathol.. 1994;18:171–179.

Keil, M.F., Stratakis, C.A. Pituitary tumors in childhood: update of diagnosis, treatment and molecular genetics. Expert Rev Neurother.. 2008;8:563–574.

Korbonits, M., Carlsen, E. Recent clinical and pathophysiological advances in non-functioning pituitary adenomas. Horm Res.. 2009;71:S123–S130.

Osamura, R.Y., Egashira, N., Kajiya, H., et al. Pathology, pathogenesis and therapy of growth hormone (GH)-producing pituitary adenomas: technical advances in histochemistry and their contribution. Acta Histochem Cytochem.. 2009;42:95–104.

Osamura, R.Y., Kajiya, H., Takei, M., et al. Pathology of the human pituitary adenomas. Histochem Cell Biol.. 2008;130:495–507.

Scheithauer, B.W., Horvath, E., Kovacs, K., et al. Plurihormonal pituitary adenomas. Semin Diagn Pathol.. 1986;3:69–82.

Scheithauer, B.W., Kovacs, K.T., Laws, E.R., Jr., et al. Pathology of invasive pituitary tumors with special reference to functional classification. J Neurosurg.. 1986;65:733–744.

Terada, T., Kovacs, K., Stefaneanu, L., et al. Incidence, pathology, and recurrence of pituitary adenomas: study of 647 unselected surgical cases. Endocr Pathol.. 1995;6:301–310.

Thapar, K., Kovacs, K., Scheithauer, B.W., et al. Proliferative activity and invasiveness among pituitary adenomas and carcinomas: an analysis using the MIB-1 antibody. Neurosurgery.. 1996;38:99–106.

Saeger, W., Lüdecke, D.K., Buchfelder, M., et al. Pathohistological classification of pituitary tumors: 10 years of experience with the German Pituitary Tumor Registry. Eur J Endocrinol.. 2007;156:203–216.

Sansur, C.A., Oldfield, E.H. Pituitary carcinoma. Semin Oncol.. 2010;37:591–593.

Syro, L.V., Ortiz, L.D., Scheithauer, B.W., et al. Treatment of pituitary neoplasms with temozolomide: A review. Cancer.. 2011;117:454–462.

Zada, G., Woodmansee, W.W., Ramkissoon, S., et al. Atypical pituitary adenomas: incidence, clinical characteristics, and implications. J Neurosurg.. 2010;114:336–344.

Adamson, T.E., Wiestler, O.D., Kleihues, P., et al. Correlation of clinical and pathological features in surgically treated craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg.. 1990;73:12–17.

Crotty, T.B., Scheithauer, B.W., Young, W.F., Jr., et al. Papillary craniopharyngioma: a clinicopathological study of 48 cases. J Neurosurg.. 1995;83:206–214.

Pettorini, B.L., Frassanito, P., Caldarelli, M., et al. Molecular pathogenesis of craniopharyngioma: switching from a surgical approach to a biological one. Neurosurg Focus.. 2010;28:E.1.

Zada, G., Lin, N., Ojerholm, E., et al. Craniopharyngioma and other cystic epithelial lesions of the sellar region: a review of clinical, imaging, and histopathological relationships. Neurosurg Focus.. 2010;28:E4.

Miscellaneous sellar/suprasellar tumors

Albright, A.L., Price, R.A., Guthkelch, A.N. Diencephalic gliomas of children. A clinicopathologic study. Cancer.. 1985;55:2789–2793.

Branch, C.L., Jr., Laws, E.R., Jr. Metastatic tumors of the sella turcica masquerading as primary pituitary tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.. 1987;65:469–474.

Coons, S.W., Rekate, H.L., Prenger, E.C., et al. The histopathology of hypothalamic hamartomas: study of 57 cases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol.. 2007;66:131–141.

Geddes, J.F., Jansen, G.H., Robinson, S.F., et al. ‘Gangliocytomas’ of the pituitary: a heterogeneous group of lesions with differing histogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol.. 2000;24:607–613.

Louis, D.N., Ohgaki, H., Wiestler, O.D., et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol.. 2007;114:97–109.

Moshkin, O., Muller, P., Scheithauer, B.W., et al. Primary pituitary lymphoma: a histological, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural study with literature review. Endocr Pathol.. 2009;20:46–49.

Phillips, J.J., Misra, A., Feuerstein, B.G., et al. Pituicytoma: characterization of a unique neoplasm by histology, immunohistochemistry, ultrastructure, and array-based comparative genomic hybridization. Arch Pathol Lab Med.. 2010;134:1063–1069.

Roncaroli, F., Scheithauer, B.W., Cenacchi, G., et al. ‘Spindle cell oncocytoma’ of the adenohypophysis: a tumor of folliculostellate cells? Am J Surg Pathol.. 2002;26:1048–1055.

Sautner, D., Saeger, W., Ludecke, D.K. Tumors of the sellar region mimicking pituitary adenomas. Exp Clin Endocrinol.. 1993;101:283–289.

Bills, D.C., Meyer, F.B., Laws, E.R., Jr., et al. A retrospective analysis of pituitary apoplexy. Neurosurgery.. 1993;33:602–608.

Flanagan, D.E., Ibrahim, A.E., Ellison, D.W., et al. Inflammatory hypophysitis – the spectrum of disease. Acta Neurochir (Wien).. 2002;144:47–56.

Paulus, W., Honegger, J., Keyvani, K., et al. Xanthogranuloma of the sellar region: a clinicopathological entity different from adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma. Acta Neuropathol.. 1999;97:377–382.

Rivera, J.A. Lymphocytic hypophysitis: disease spectrum and approach to diagnosis and therapy. Pituitary.. 2006;9:35–45.

Scanarini, M., d’Avella, D., Rotilio, A., et al. Giant-cell granulomatous hypophysitis: a distinct clinicopathological entity. J Neurosurg.. 1989;71:681–686.

Semple, P.L., De Villiers, J.C., Bowen, R.M., et al. Pituitary apoplexy: do histological features influence the clinical presentation and outcome? J Neurosurg.. 2006;104:931–937.