12 Neonatal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

• In newborn resuscitation, simultaneous auscultative assessment of the heart rate and respirations should precede more advanced interventions.

• Because visual determination has been found to be unreliable, pulse oximetry with the minimal oxygen supplementation necessary to maintain adequate oxygen saturation should be used to assess newborns.

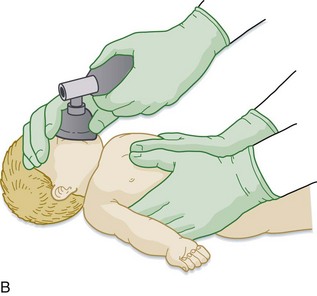

• Endotracheal intubation should be considered for tracheal suctioning of meconium, heart rates below 100 beats/min that do not respond to initial bag-valve-mask ventilation, prolonged bag-valve-mask ventilation or chest compressions, administration of medications, and other special considerations such as congenital diaphragmatic hernia and extremely low birth weight.

• If the heart rate remains below 60 beats/min despite respiratory support, chest compressions should be performed at a rate of at least 100 compressions per minute via the two-finger or chest-encircling technique. The chest-encircling technique is preferred for chest compressions. The ratio of compressions to ventilations should be 3 : 1, with 90 compressions and 30 breaths to achieve approximately 120 events per minute to maximize ventilation at an achievable rate. Each event will be allotted approximately  second, with exhalation occurring during the first compression after each ventilation.

second, with exhalation occurring during the first compression after each ventilation.

Perspective

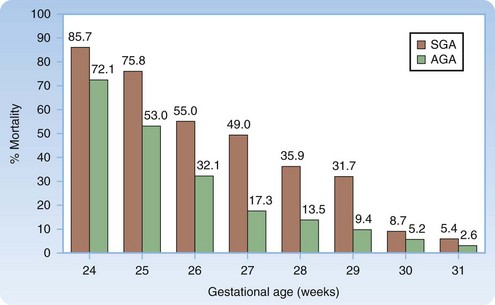

Approximately 10% of newborns require assistance after birth to achieve spontaneous breathing, and 1% need additional support. The likelihood of survival can be estimated from the gestational age and birth weight (Fig. 12.1).1

Survival with Comorbid Conditions

A 2001 study reviewing more than 700 neonatal intensive care unit admissions involving infants born at or before 25 weeks’ gestation found that survivors (63%) had a high incidence of chronic lung disease (51%), high-grade retinopathy of prematurity (32%), intraventricular hemorrhage (44%), nosocomial infection (38%), and necrotizing enterocolitis (11%).2

Anatomy

Anatomic considerations for the neonatal airway are similar to those discussed for pediatric patients (see Chapter 13), with the exception that the structures are even smaller and more anterior and superior, thus making visualization of the vocal cords an even greater challenge.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

“Yes” answers to the following three questions identify babies who do not require support after birth but can be dried, covered, and kept with the mother if desired.3

Interventions and Procedures: Resuscitation Steps

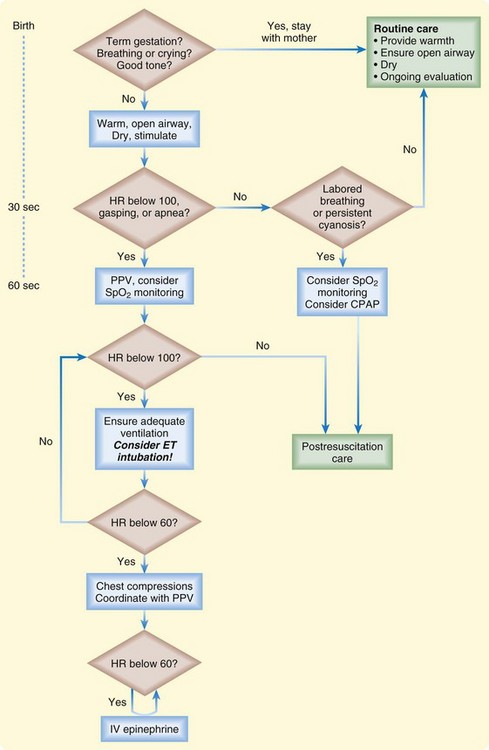

Figure 12.2 lists the steps in neonatal resuscitation.

Fig. 12.2 Newborn resuscitation algorithm.

(Modified from Kattwinkel J, Perlman JM, Aziz K, et al. Part 15: neonatal resuscitation: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation 2010;122:S909-19.)

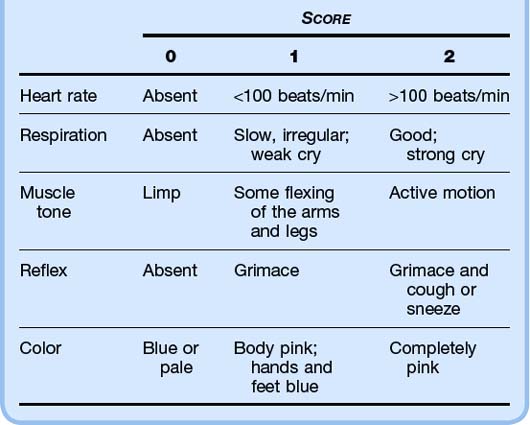

Apgar scores are measured at 1 minute and 5 minutes after delivery. These scores are used to (1) predict which infants will require resuscitation and (2) identify infants who are at higher risk for neonatal mortality. A score of 7 or higher is reassuring (Table 12.1).

Airway

The American Heart Association (AHA) no longer recommends routine intrapartum oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal suctioning because it has been shown to be associated with cardiopulmonary complications in healthy neonates. Oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal suctioning should be reserved for newborns with obvious upper airway obstruction and associated respiratory distress.3,4

Meconium-stained amniotic fluid occurs in up to 20% of deliveries, and as many as 9% of infants with meconium-stained amniotic fluid experience meconium aspiration syndrome (MAS), which carries a modern-day mortality rate of up to 40%.4

MAS occurs when the fetus aspirates meconium before or during birth, which leads to obstruction of the airways, atelectasis, severe hypoxia, inflammation, acidosis, and infection.5 The AHA guidelines regarding the management of a newborn with potential meconium aspiration make no distinction between thin and thick meconium because both have shown to lead to MAS.

In the absence of randomized controlled trials on routine tracheal suctioning of depressed infants born through meconium-stained amniotic fluid, the 2005 newborn resuscitation guidelines have not changed significantly. Thus, a nonvigorous newborn with meconium-stained amniotic fluid should not be suctioned on the mother’s perineum. Avoiding such suctioning prevents undue stimulation, which would lead to breathing and aspiration of meconium before endotracheal suctioning.6 Endotracheal intubation (ETI) and suctioning of meconium should be performed with a 10 French (F) to 14 F suction catheter and a meconium aspirator attached to an endotracheal tube. If intubation attempts are prolonged, bag-mask ventilation should not be delayed, especially when bradycardia is present.4

A vigorous neonate born with meconium-stained amniotic fluid does not require endotracheal suctioning for any level of meconium staining. Endotracheal suctioning has shown no benefit in this setting because the meconium has already caused irreversible damage to the lower airways. Vigorous is defined as having strong respiratory effort, good muscle tone, and a heart rate higher than 100 beats/min.7

Breathing

Methods to stimulate breathing in neonatal resuscitation are as follows:

Positive pressure ventilation (PPV) via a bag-valve-mask device at a rate of 40 to 60 breaths/min is indicated for the following situations3,4:

• The infant is apneic or gasping after warming, stimulation, and administration of blow-by oxygen.

• The heart rate remains lower than 100 beats/min after the preceding methods have been applied.

In the absence of meconium-stained amniotic fluid, laryngeal mask airways may be used in a newborn weighing more than 2000 g or delivered at more than 34 weeks’ gestation and requiring assisted ventilation, but not chest compressions.8

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) delivered via face mask immediately after delivery may be used in a neonate with respiratory effort but significant distress.9 Devices that provide some level of CPAP include standard self-inflating bags, flow-inflating bags, and predetermined CPAP devices such as the Neopuff Infant Resuscitator (Fisher and Paykel, Auckland, NZ). Benefits of CPAP include reduced need for intubation, diminished work of breathing, reduced incidence of apnea, decreased inspiratory resistance, and improved oxygenation. Drawbacks include an increased risk for pneumothorax and those related to the risk associated with overdistention, which can result in reduced pulmonary perfusion, diminished cardiac output, and ultimately, ventilation-perfusion mismatch. The current AHA recommendations allow either CPAP or intubation to be used in infants requiring ventilatory support.4

Guidelines for ETI in neonatal resuscitation are as follows3,4:

• Tracheal suctioning is needed for nonvigorous newborns with meconium-stained amniotic fluid.

• Bag-valve-mask ventilation is prolonged or ineffective.

• Chest compressions are prolonged.

• Administration of medications by endotracheal tube is desired.

• Special considerations include conditions such as congenital diaphragmatic hernia or extremely low birth weight.

Circulation

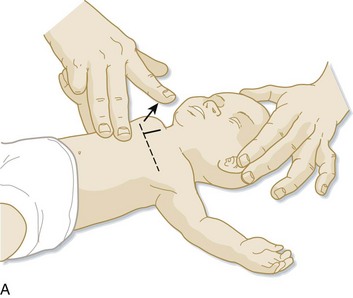

It is recommended that assessment of the heart rate be performed via auscultation at the anterior surface of the chest. However, if palpation is used, the umbilical pulse should be used while recognizing that this method may underestimate the heart rate. If the heart rate remains below 60 beats/min despite respiratory support, chest compressions (on the lower third of the sternum and at a depth of one third the diameter of the chest) should be performed at a rate of at least 100 per minute with the two-finger or the preferred chest-encircling technique (Fig. 12.3). At this point, the ratio of chest compressions to breaths should be 3 : 1 unless a cardiac cause is suspected, in which case a 15 : 2 ratio should be considered.

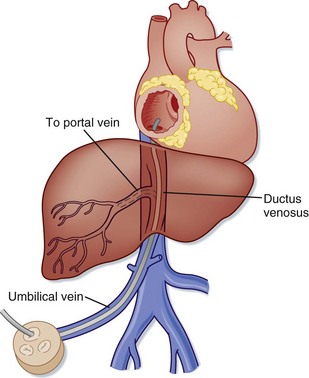

If an intravenous (IV) line cannot be placed, an umbilical catheter can be used. The umbilical vein (UV) may be used for blood sampling, fluid or drug infusion, and monitoring of blood pressure and central venous pressure. Anatomically, there are typically two umbilical arteries (UAs) and one UV. The UV is usually in the 12-o’clock position and has a thinner wall and wider lumen than the UAs. The UV is often described as resembling a “smiley face.” In emergency situations the UV is the preferred vessel to access because the UAs are often tortuous and difficult to cannulate. The umbilicus should be prepared with a bactericidal solution and draped, and a silk suture should be placed around the base of the umbilical stump. The distal end of the stump is cut off, and the vessels are occluded to prevent blood loss. A 3.5 to 5.0 F catheter is flushed with saline and inserted into the lumen of the desired vessel. The UV catheter should be advanced just to the point where good blood return is obtained (Fig. 12.4). Plain radiographs should be taken to confirm placement. Complications of umbilical catheters include hemorrhage, infection, air embolism, and perforation of a blood vessel.

Maintenance of Temperature

Some evidence indicates that induced hypothermia (33.5° C to 34.5° C) may decrease the rate of death or disability (or both) in asphyxiated newborns.10 Using clearly defined protocols, infants born at greater than 36 weeks’ gestation with suspected severe hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy should be treated with therapeutic hypothermia within 6 hours. If these protocols are not in place, at the very least, hyperthermia should be strictly avoided.3,4

Resuscitation Medications and Volume Replacement

If volume replacement is necessary, isotonic crystalloid is recommended at 10 mL/kg, with repeated dosing as dictated by the clinical situation. Caution should be used when giving fluids because rapid newborn volume expansion has been associated with intraventricular hemorrhage (Tables 12.2 and 12.3). Glucose regulation is particularly important during the poststabilization period in an asphyxiated newborn, whose glycogen stores can be depleted rapidly. Although a target glucose level has not been established, a serum glucose level greater than 40 mg/dL should be maintained with the administration of 10% dextrose in water (D10W).

Table 12.3 Medications for Pediatric Resuscitation and Arrhythmias

| MEDICATION | DOSE | REMARKS |

|---|---|---|

| Adenosine | 0.1 mg/kg (maximum: 6 mg) Repeat: 0.2 mg/kg (maximum: 12 mg) |

Monitor the ECG Rapid bolus IV/IO |

| Amiodarone | 5 mg/kg IV/IO; repeat up to 15 mg/kg Maximum: 300 mg |

Monitor the ECG and blood pressure Adjust the administration rate to urgency (give more slowly when a perfusing rhythm present) Use caution when administering with other drugs that prolong the QT interval (consider expert consultation) |

| Atropine | 0.02 mg/kg IV/IO 0.03 mg/kg ET* Repeat once if needed Minimum dose: 0.1 mg Maximum single dose: Child: 0.5 mg Adolescent: 1 mg |

Higher doses may be used with organophosphate poisoning |

| Calcium chloride (10%) | 20 mg/kg IV/IO (0.2 mL/kg) | Slowly Adult dose: 5-10 mL |

| Epinephrine | 0.01 mg/kg (0.1 mL/kg 1 : 10,000) IV/IO 0.1 mg/kg (0.1 mL/kg 1 : 1000) ET*† Maximum dose: 1 mg IV/IO; 10 mg ET |

May repeat q3-5min |

| Glucose | 0.5-1 g/kg IV/IO | D10W: 5-10 mL/kg D25W: 2-4 mL/kg D50W: 1-2 mL/kg |

| Lidocaine | Bolus: 1 mg/kg IV/IO Maximum dose: 100 mg Infusion: 20-50 mcg/kg/min |

|

| Magnesium sulfate | 25-50 mg/kg IV/IO over 10-20 min; faster with torsades de pointes Maximum dose: 2 g |

|

| Naloxone | <5 yr or ≤20 kg: 0.1 mg/kg IV/IO/ET*‡ ≥5 yr or >20 kg: 2 mg IV/IO/ET*‡ |

Use lower doses to reverse respiratory depression associated with therapeutic opioid use (1-15 mcg/kg) |

| Procainamide | 15 mg/kg IV/IO over 30-60 min Adult dose: 20-mg/min IV infusion up to total maximum dose of 17 mg/kg |

Monitor ECG and blood pressure Use caution when administering with other drugs that prolong the QT interval (consider expert consultation) |

| Sodium bicarbonate | 1 mEq/kg per dose IV/IO slowly | After adequate ventilation |

D10W, 10% dextrose in water; ECG, electrocardiogram; ET, via endotracheal tube; IO, intraosseously; IV, intravenously.

* Flush with 5 mL of normal saline and follow with five ventilations.

† See text for neonatal ET dosing.

‡ Not recommended in neonates.

From 2005 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Part 12: pediatric advanced life support. Circulation 2005;112(Suppl IV):IV-167-IV-187.

Table 12.2 Medications to Maintain Cardiac Output and for Postresuscitation Stabilization

| MEDICATION | DOSE RANGE* | COMMENT |

|---|---|---|

| Inamrinone | 0.75-1 mg/kg IV/IO over 5 min; may repeat ×2; then 2-20 mcg/kg/min | Inodilator |

| Dobutamine | 2-20 mcg/kg/min IV/IO | Inotrope, vasodilator |

| Dopamine | 2-20 mcg/kg/min IV/IO | Inotrope, chronotrope, renal and splanchnic vasodilator in low doses, pressor in high doses |

| Epinephrine | 0.1-1 mcg/kg/min IV/IO | Inotrope, chronotrope, vasodilator in low doses, pressor in higher doses |

| Milrinone | 50-75 mcg/kg IV/IO over 10-60 min, then 0.5-0.75 mcg/kg/min | Inodilator |

| Norepinephrine | 0.1-2 mcg/kg/min | Inotrope, vasopressor |

| Sodium nitroprusside | 1-8 mcg/kg/min | Vasodilator, prepare only in D5W |

D5W, 5% dextrose in water; IO, intraosseously IV, intravenously.

* Alternative formula for calculating an infusion: Infusion rate (mL/hr) = Weight (kg) × Dose (mg/kg/min) × 60 (min/hr)] ÷ Concentration (mg/mL).

From 2005 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Part 12: pediatric advanced life support. Circulation 2005;112(Suppl IV):IV-167-87.

Naloxone administration should generally be avoided in the resuscitation of a newborn at the time of delivery; instead, one should concentrate on support of breathing and the circulation. Administration of naloxone to mothers with known opioid addiction can have adverse outcomes and is not recommended by the AHA.3

Bicarbonate is not routinely recommended in the acute resuscitation of a newborn because of studies showing deleterious effects, including depression of myocardial function, intracellular acidosis, reductions in cerebral blood flow, and risk for intracranial hemorrhage.11

1 Regev RH, Lusky A, Dolfin T, et al. Excess mortality and morbidity among small-for-gestational-age premature infants: a population-based study. J Pediatr. 2003;143:186–191.

2 Chan K, Ohisson A, Synnes A, et al. Survival, morbidity, and resource use of infants of 25 weeks’ gestational age or less. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:220–226.

3 Perlman JM, Wylie J, Kattwinkel J, et al. on behalf of the Neonatal Resuscitation Chapter Collaborators. Part 11: neonatal resuscitation: 2010 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recommendations. Circulation. 2010;122:S516–S538.

4 Kattwinkel J, Perlman JM, Aziz K, et al. Part 15: neonatal resuscitation: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010;122:S909–S919.

5 Velaphi S, Vidyasagar D. Intrapartum and postdelivery management of infants born to mothers with meconium-stained amniotic fluid: evidence-based recommendations. Clin Perinatol. 2006;33:29–42.

6 Vain NR, Szyld EG, Prudent LM, et al. Oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal suctioning of meconium-staining neonates before delivery of their shoulders: multicentre, randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:597–602.

7 Wiswell TE, Gannon CM, Jacob J, et al. Delivery room management of the apparently vigorous meconium-stained neonate: results of the multicenter, international collaborative trial. Pediatrics. 2000;105:1–7.

8 Trevisanuto D, Micaglio M, Pitton M, et al. Laryngeal mask airway: is the management of neonates requiring positive pressure ventilation at birth changing? Resuscitation. 2004;62:151–157.

9 Morley CJ, Davis PG, Doyle LW, et al. Nasal CPAP or intubation at birth for very preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:700–708.

10 Azzopardi DV, Strohm B, Edwards AD, et al. Moderate hypothermia to treat perinatal asphyxial encephalopathy. N Engl J Med.. 2009;361:1349–1358.

11 Wyckoff M, Perlman MB. Use of high-dose epinephrine and sodium bicarbonate during neonatal resuscitation: Is there proven benefit? Clin Perinatol. 2006;33:141–151.