Needle blocks of the eye

Anatomy

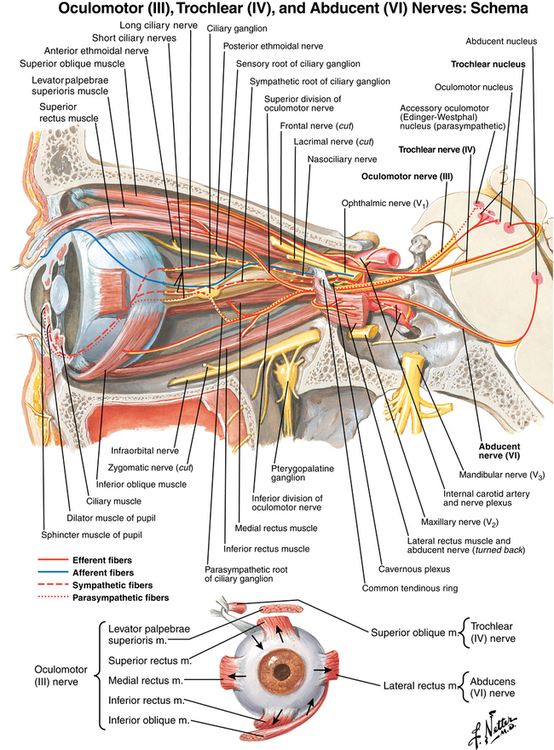

The ciliary ganglion, a parasympathetic ganglion that is 1 to 2 mm in diameter, is located approximately 1 cm anterior to the posterior wall of the orbit between the lateral surface of the optic nerve and the ophthalmic artery (Figure 121-1). Parasympathetic fibers originating in the oculomotor nerve and postganglionic fibers supply the ciliary body and sphincter pupillae muscles. The nasociliary nerve, a branch of the ophthalmic nerve, supplies the sensory innervation of the cornea, iris, and ciliary body via the short ciliary nerves, which are 6 to 10 small filaments accompanying the ciliary arteries.

Types of eye blocks

Intraconal block

An intraconal block primarily involves the ciliary ganglion, ciliary nerves, and cranial nerves II, III, and VI. The classic Atkinson technique (described in Box 121-1, Figure 121-2, A to C) typically uses a 35-mm, 25-gauge, blunt needle inserted to a depth of one third of the distance medially from the outer lower orbital margin. It requires not only deep injection of a local anesthetic agent into the orbit, but also a separate block of the seventh cranial nerve to provide akinesia and anesthesia to the surgical field.

Contraindications

Eye blocks are not used in procedures that are anticipated to last longer than 90 min, nor in patients younger than 15 years of age. Any factor that precludes the patient from following commands or lying still during the procedure or increases the patient’s bleeding risk is also a contraindication to the use of an eye block (Box 121-2).

Complications

Retrobulbar hemorrhage

Oculocardiac reflex

An oculocardiac reflex (see Chapter 38) manifested by bradycardia, arrhythmias, and even periods of cardiac asystole—may occur acutely with block placement or expanding retrobulbar hemorrhage. The latter may happen some hours after a retrobulbar hemorrhage as additional blood extravasates. The reflex is trigeminal-vagal via the ciliary branch of the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve. If an arrhythmia develops, surgical manipulation should be stopped and intravenous atropine (0.007 mg/kg) given.