Nasogastric and Feeding Tube Placement

Properties of NG and Feeding Tubes

Polypropylene is the material most commonly used for Levin and Salem sump NG tubes (Fig. 40-1), but it is too rigid for long-term use as a feeding tube. Polypropylene tubes are less likely to kink than others but are more capable of creating a false passage during placement. Latex (rubber) tubes are moderately firm, require greater lubrication for passage, are relatively thick walled, and induce a greater foreign body reaction than do tubes made of other common materials. Latex, especially in latex balloons, deteriorates more rapidly than other material does.1 Foley catheters are primarily latex, although silicone Foley catheters are available for patients with latex allergies. Silicone tubes are thin walled, pliable, and nonreactive; however, the walls of silicone tubes are weaker and may rupture if fluid is introduced into a kinked tube.2 Polyurethane tubes are nonreactive and relatively durable. Rigidity varies from manufacturer to manufacturer, depending on the thickness of the tube. A stylet may aid in the passage of polyurethane and silicone tubes, but it increases rigidity and the potential for tissue dissection, especially with tubes that have a small distal end-bulb.3 Some feeding tubes have weights, which are usually made of tungsten and are nontoxic if released into the GI tract.

NG Tube Placement

Indications and Contraindications

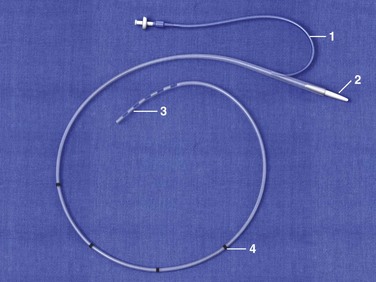

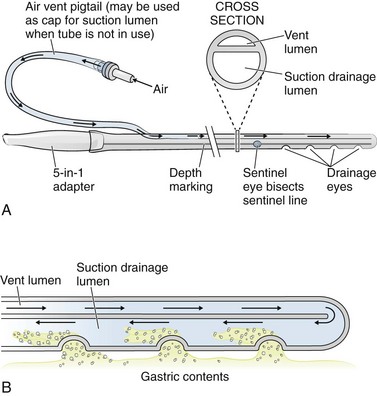

The simplest NG tube is the Levin tube, which has a single lumen and multiple distal “eyes.” The advantage of the Levin tube is its relatively large internal diameter (ID) in proportion to its external diameter. The theoretical disadvantage is that a Levin tube should not be left hooked up to suction after the initial contents of the stomach have been drained because the suction will cause the stomach to invaginate into the eyes of the tube and thereby blocking future tube function and potentially cause injury to the stomach lining. Levin tubes are therefore rarely used in the ED. The Salem sump tube is preferred over the Levin tube for chronic use as a drainage device because it has a separate (blue-colored) channel that vents the distal main lumen to the atmosphere (Fig. 40-2). This vent helps prevent excessive vacuum from forming at the tip of the tube. Note that both intermittent suction and wall unit vacuum can exceed the venting capacity of the second lumen, so the vacuum setting should be less than 120 mm Hg.

For the evaluation and treatment of upper GI bleeding, indications for NG tubes differ among clinicians, and practices vary widely. Clinical judgement prevails as the best arbitrator, but the true clinical value of an NG tube in patients with GI bleeding is probably less than traditionally promulgated. Although insertion of an NG tube may prompt earlier endoscopy, the procedure has not been demonstrated to improve clinical outcomes.4 NG aspiration can help localize bleeding in only a minority of patients with GI hemorrhage. Patients who vomit a significant amount of proven bloody material have had upper GI bleeding; they do not need an NG tube for diagnosis. Such patients are best evaluated by endoscopy, although when a history of bleeding is suspected, stomach aspiration may have a role in diagnosis to confirm the presence of blood. In patients without hematemesis, NG aspiration uncovers less than half the patients with upper GI hemorrhage and thus cannot be used to unequivocally rule out upper GI bleeding. Even a rapidly bleeding duodenal ulcer may not produce blood in the stomach. Some contend that emptying a markedly dilated stomach of blood and stomach contents may reduce the rate of bleeding, but data are lacking. Patients with presumptive upper GI bleeding, which includes those with melena, those younger than 50 years old, and those with a hematocrit lower than 30, need upper endoscopy.5,6 Patients passing clots or blood per rectum or those with known previous lower GI bleeding are usually experiencing lower GI bleeding.6 Except when frankly bloody fluid is obtained, a nasogastric aspirate is diagnostically unhelpful. Small bits of darkish material, bloody mucus, or positive Gastroccult or guaiac tests probably represent sequelae of the procedure, whereas a clear appearance and negative tests still miss most bleeding distal to the stomach. Patients with a bleeding pattern indicative of a Mallory-Weiss tear may need neither an NG tube nor endoscopy.

Increasingly, the literature suggests that most other causes of vomiting are best controlled with medication. Postoperative ileus ends sooner and patients recover faster without an NG tube after various studied abdominal surgeries.5 NG tubes prolong the hospital stay, pain, and hyperamylasemia in those with mild to moderate pancreatitis.7,8 Many patients are better off without an NG tube from the point of view of safety, comfort, and speed of recovery.

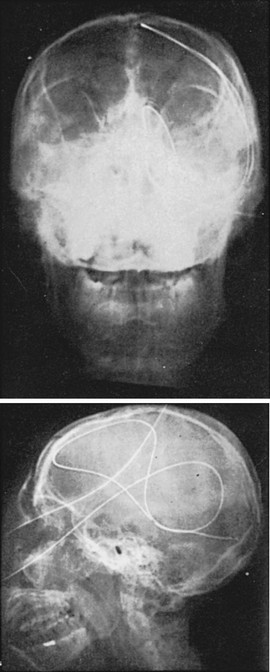

In an awake and alert patient with a preserved gag reflex, passage of a NG tube has not been demonstrated to result in significant pulmonary aspiration, even when vomiting occurs during passage. NG tubes are, however, contraindicated in patients with a special predisposition to injury from placement of the tube. Patients with facial fractures who have sustained an injury to the cribriform plate may suffer intracranial penetration with a blindly placed nasal tube.9 Severe coagulopathy is a relative contraindication to passage of an NG tube. In patients with a coagulopathy or significant facial or head trauma, an NG tube passed through the mouth may be a better alternative (Fig. 40-3). Patients who have esophageal strictures or a history of alkali ingestion may suffer esophageal perforation. Gagging will decrease venous return and increase cervical and intracranial venous pressure. Comatose patients may vomit during or after NG tube placement. Indwelling NG tubes predispose patients to pulmonary aspiration because of tube-induced hypersalivation, depressed cough reflex, or mechanical or physiologic impairment of the glottis.7 Aspiration is also quite common with nasoenteral feedings in debilitated patients, hence the use of a gastrostomy feeding tubes for this condition. An NG tube should be avoided when possible in patients who have undergone gastric bypass surgery or lap banding procedures.

Extended irrigation of the stomach with water in a patient with upper GI hemorrhage can lower serum potassium levels,10 and animal studies suggest that cold water lavage can cause rather than control bleeding.11,12 No study has shown irrigation to be effective in the control of bleeding,13,14 and vigorous lavage with cold water may lower the body temperature. Erythromycin has been demonstrated to be effective in clearing the stomach for endoscopy,15,16 and its success is better substantiated than irrigation.

Procedure

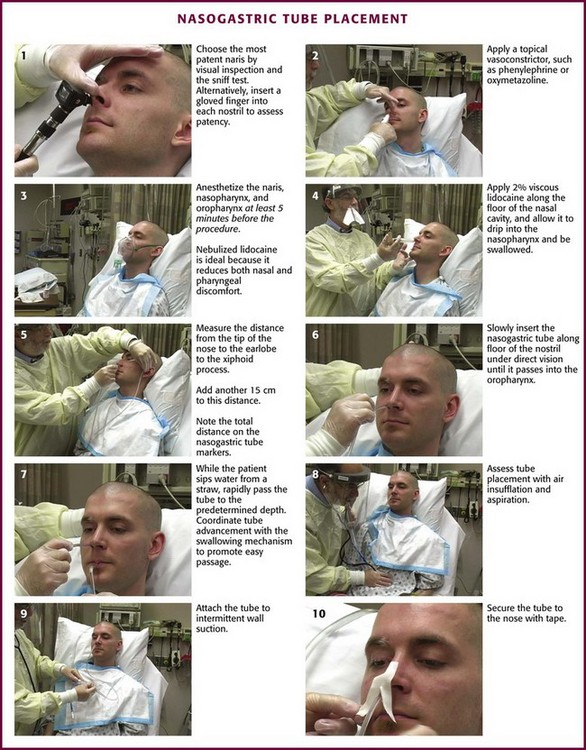

Explain the procedure to the patient. Written informed consent is not standard. If the patient is alert, raise the head of the bed so that the patient is upright. Place a towel over the patient’s chest to protect the gown, and place an emesis basin on the patient’s lap.17 Position the tube (typically a 16- or 18-Fr sump) so that the insertion distance can be estimated, and mark the distance with tape or by noting the markers printed on the proximal end of the tube. A simple method is to measure the tube from the xiphoid to the earlobe and then to the tip of the nose. Then add 15 cm (6 inches) to this number (Fig. 40-4, step 5).18 It is a common error to fail to estimate the proper length of tube before passage, which can result in the tip of the tube positioned in the esophagus or coiled excessively in the stomach. Check the nares for obstruction. Assess patency by direct visualization, by gentle digital nasal examination, and by having the patient sniff while first one and then the other nostril is occluded. Pass the tube down the more patent naris.

Figure 40-4 Nasogastric tube placement.

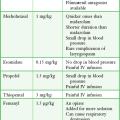

Relief of Discomfort

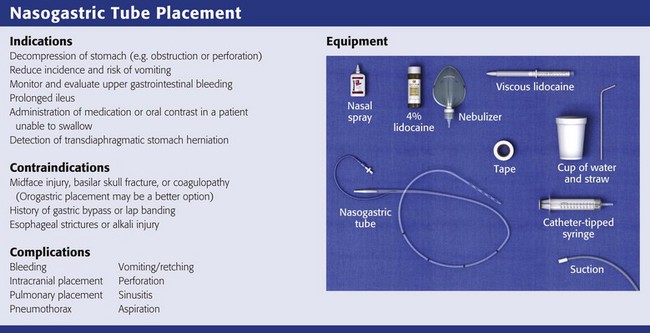

Ameliorate the pain and gagging associated with tube placement by using vasoconstrictors, topical anesthetics, and antiemetics. Because patients rate NG tube placement as very painful, one of the most painful procedures performed in the ED, use these adjuncts whenever time and the clinical situation permit (Fig. 40-5). Spray topical vasoconstrictors, such as phenylephrine (0.5% Neo-Synephrine) or oxymetazoline (0.05% Afrin), into both nares at first in case one side proves to be problematic (see Fig. 40-4, step 2). The nares, nasopharynx, and oropharynx should all be anesthetized at least 5 minutes before the procedure. Gagging is reduced if the pharynx is anesthetized as well as the nose. Combinations of tetracaine, butyl aminobenzoate, and benzocaine (Cetacaine), nebulized or atomized (spray cans or bottles) lidocaine (4% or 10%), and lidocaine gels (2%) are most commonly used. Lidocaine preparations of 10% are most useful. Lidocaine may be nebulized and delivered by face mask with the equipment used to administer bronchodilators to asthmatics (see Fig. 40-4, step 3). This method has been found to be superior to lidocaine spray for reducing gagging and vomiting and increasing the chance of successful passage.19,20 Cullen and coworkers concluded that nebulized nasal and pharyngeal lidocaine (4 mL of a 10% solution) reduces the discomfort associated with passage of an NG tube better than placebo does and without any lidocaine-related toxicity.21

After a topical vasoconstrictor and anesthetic are administered, lubricate the tube with viscous lidocaine or lidocaine jelly.22 Lubrication and anesthesia of the nares can be facilitated by using a syringe (without needle) filled with 5 mL of an anesthetic lubricant, such as 2% lidocaine gel (Fig. 40-4, step 4). Simply putting anesthetic jelly on the tube just before insertion will not provide any anesthesia. Topical anesthetics are generally quite safe, but pay attention to the total dose of anesthetic administered to avoid toxicity.23 Note that each milliliter of a 10% lidocaine solution contains 100 mg of lidocaine and can be absorbed systemically. In rare cases, topical benzocaine has caused methemoglobinemia even with the relatively small amounts used for endoscopy.24

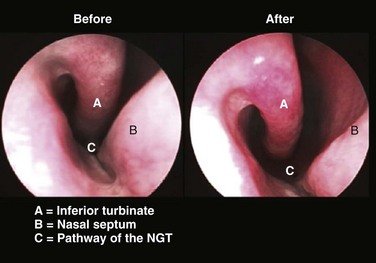

Under direct vision, not blind forcing, insert the tube gently into the naris along the floor of the nose under the inferior turbinate and not upward toward the nasal bridge (Fig. 40-6; also see Fig. 40–4, step 6). If mild resistance is felt in the posterior nasopharynx, apply gentle pressure to overcome this resistance. If significant resistance is encountered, it is better to try the other nostril because bleeding or dissection into retropharyngeal tissue may occur if force is used. Once the tube passes into the oropharynx, pause to help the patient regain composure and enhance the chance for cooperation with the rest of the procedure.

If the patient is alert and cooperative, a common option is to ask the patient to sip water from a straw and swallow while you advance the tube into and down the esophagus (see Fig. 40-4, step 7). This may facilitate passage of the tube. Once the tube is in the nasopharynx, flex the patient’s neck to direct the tube into the esophagus rather than the trachea. In an intubated, anesthetized, or paralyzed patient, two stacked positive pressure breaths lasting 1 to 2 seconds each via a face mask provide similar relaxation of the upper esophageal sphincter for a brief 4- to 5-second window, and this markedly increases successful tube placement.25

Some gagging during the procedure is common and is not an indication to halt attempts at passage. Withdraw the tube promptly into the oropharynx if the patient has excessive choking, gagging, coughing, or a change in voice or condensation appears on the inner surface of the tube because this indicates the possibility of passage of the tube into the trachea. Inspect the tube by way of the mouth to detect coiling or respiratory passage. If the tube is lateral to the midline, this suggests correct position in the esophagus.26 Once the tube is in the esophagus, advance it rapidly to the previously determined depth. Passing the tube slowly prolongs discomfort and may precipitate more gagging.17

Confirmation of Tube Placement

A quick and simple method of confirmation is to insufflate air into the NG tube and auscultate for a rush of air over the stomach (see Fig. 40-4, step 8). If increased pressure is required to instill the air or if no sounds are heard, the tube may be malpositioned or kinked. Suspect an esophageal location if the patient immediately burps on insufflation.

If alert and cooperating, the patient will feel whether the tube is entering the trachea or lungs and can notify the inserter. Unfortunately, if the patient is comatose, struggling, or demented, the tube may pass into the lungs unrecognized. Insufflation is often insufficient to detect this type of malpositioning.3 The insufflation test is also unreliable in detecting a tube that has advanced past the stomach and into the small bowel.27 In such patients, radiographic verification may be prudent.

Aspiration of stomach contents, especially if pH-tested, is more reliable and can be performed if positioning is in question. If the pH is less than 4, there is an approximately 95% chance that the tube is in the stomach and nonrespiratory placement is almost guaranteed.28 Although aspirated fluid can occasionally be obtained from the lung or pleural space, the pH should be 5.5 or higher.29 Approximately 4% of correctly placed tubes have aspirates with a pH higher than 5.5. Causes include duodenal reflux, antacids, H2 blockers, or recent instillation of formula or medications.29

If awake and cooperative, ask the patient to talk. If the patient cannot speak, suspect respiratory placement. Note that with small-bore tubes, patients may still be able to speak despite tracheal placement.30

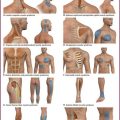

Securing the Tube

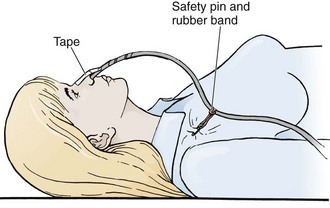

The NG tube is generally secured to the patient with tape attached to both the tube and nose (Fig. 40-4, step 10). A butterfly bandage (or tape on each side of the nose) that coils around the NG tube is a typical approach. The nose and tube should both be clean and prepared with tincture of benzoin if possible. If the tape should let go or require repositioning, both the tape and the tincture of benzoin must be replaced. It is wise to also secure the tube to the patient’s gown so that a tug on the tube will encounter this resistance before pulling on the tape securing the tube to the patient’s nose. A rubber band tied around the tube with a slipknot (Fig. 40-7) and pinned to the gown near the patient’s shoulder is effective. It is critical to ensure that the tube is secured in such a way that it does not press on the medial or lateral aspect of the nostril. Necrosis or bleeding can result if a tube is not secured correctly.

Placement Issues

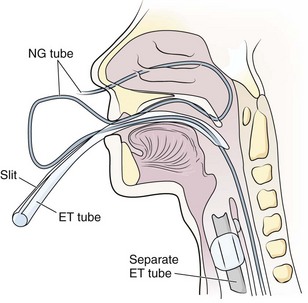

If less traumatic strategies fail, an ET tube can be prepared with an ID that is slightly larger than the external diameter of the NG tube. Slit it along its lesser curvature from the proximal end to a point 3 cm from its distal end. Pass the NG tube through a naris into the oropharynx. Visualize the tip of the tube with a laryngoscope, grasp it with Magill forceps, and pull it out of the mouth. Pass the slit ET tube (generally 8 mm in ID) through the mouth into the esophagus.31 Alternatively, pass a 7-mm-ID slit ET tube directly through the nose into the esophagus.32 Passage into the esophagus is facilitated by the stiffness of the larger ET tube and does not require active swallowing. Thread the tip of the NG tube into the ET tube and advance it into the stomach (Fig. 40-8). Remove the slit ET tube from the esophagus. When the distal part of the ET tube is visible, slit the unslit 3-cm distal part with scissors. Remove the ET tube, and the NG tube will remain in place.33 Advance any slack tubing with forceps or pull it back nasally, depending on the final depth required for the NG tube. The technique can also be performed by passing the slit ET tube nasally, which saves the trouble of orally advancing or nasally retracting any slack in the tubing.33,33 Make sure that the NG tube can pass into the 7-mm-ID tube and that the ET tube is well lubricated inside and out.

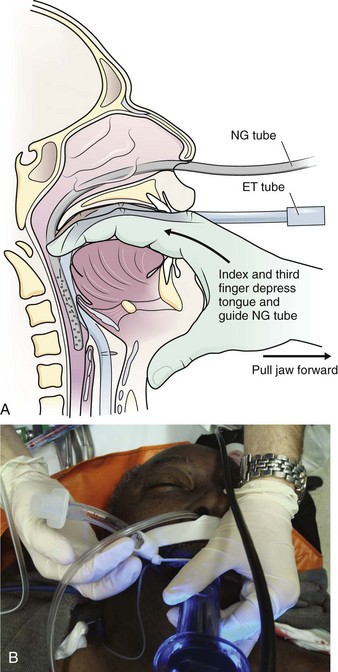

In a particularly passive, intubated, sedated, unconscious, or toothless patient, guiding the NG tube with fingers into the pharynx is occasionally successful (Fig. 40-9A).34 Displacing the larynx forward by manually gripping and lifting the thyroid cartilage can aid in inserting the tube,35 as can simple jaw elevation. A soft nasopharyngeal airway, well lubricated, is at times easier to pass nasally than an NG tube, and then the lubricated NG tube can be passed through it. In addition, it affords some protection to the nasal mucosa if multiple attempts at passing the NG tube are necessary or if it is particularly important to minimize bleeding or trauma. Cooling an NG tube increases its rigidity, and coiling it can increase the curvature of the tube, both of which may help pass the tube. Alternatively, the NG tube and larynx can be visualized with a laryngoscope, endoscope, or the GlideScope (Fig. 40-9B).35 Under laryngeal visualization, manipulation and lifting of the jaw and neck flexion can help align the tube for passage under direct vision into the esophagus.

Ultimately, if all other methods fail, place a flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope or esophagoscope into and through the esophagus under direct visualization.36 Thread a guidewire into the stomach. Place the NG tube over the guidewire into the stomach and then remove the guidewire.37

Complications

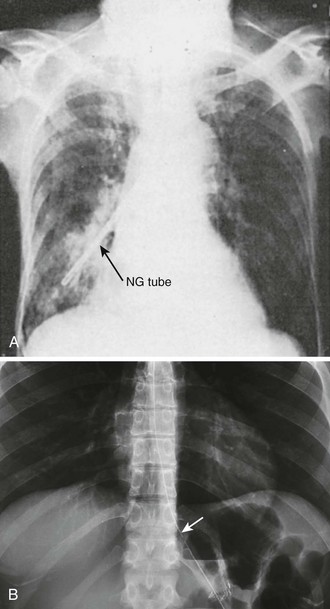

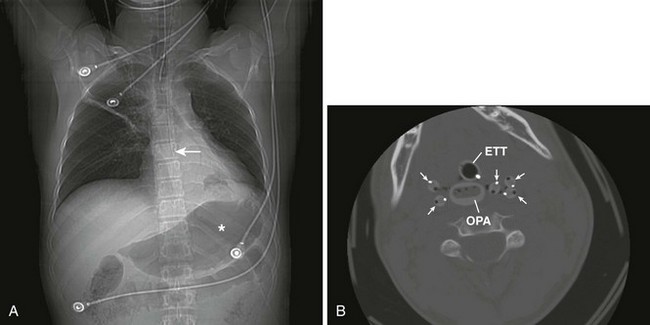

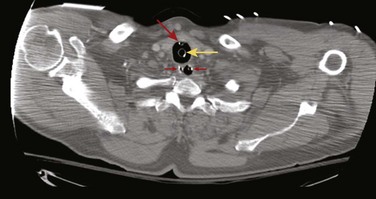

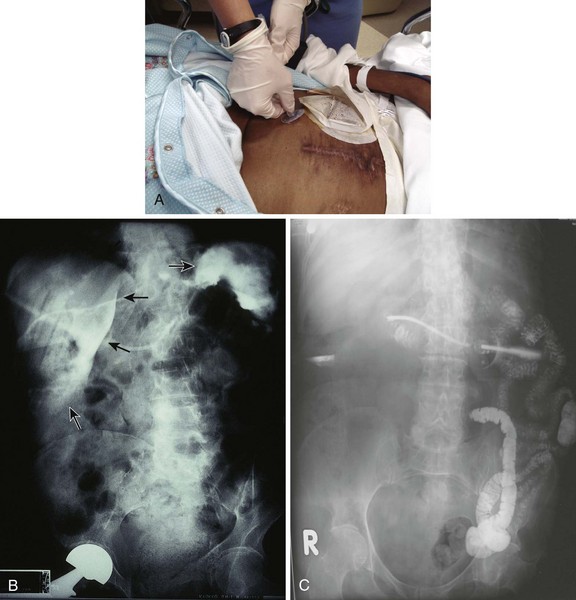

Complications of standard NG tube placement are similar to the problems noted with placement of an NG feeding tube. The complications related to tube misplacement are discussed in that section. In addition, clinicians placing an NG tube in a patient with neck injuries should be cautious of potentiating cervical spine injuries with excessive motion during passage (especially in association with coughing and gagging in an awake patient). Furthermore, passage of an NG tube in an awake patient with a penetrating neck wound may exacerbate hemorrhage should coughing or gagging result. Particularly serious forms of tube misplacement are pulmonary placement (Fig. 40-10) and intracranial placement (Fig. 40-11). In confusing cases, a CT scan will clarify most misplacement issues (Figs. 40-12 and 40-13). NG tubes, when in place for prolonged periods, are a common cause of innocuous gastric bleeding and gastric erosions.

Tension gastrothorax can develop in patients with an intrathoracic stomach. It can occupy much of the left hemithorax and thus displace the heart and lungs and cause a clinical syndrome identical to tension pneumothorax. Even though successful passage of an NG tube will relieve tension gastrothorax, the high pressures of a tension gastrothorax often develop because torsion of the stomach in the chest prevents egress of air; such torsion may also prevent ingress of the therapeutic NG tube. The condition is rare enough that further emergency therapy is based on case reports rather than substantial series. Relief of tension gastrothorax has been accomplished by transthoracic puncture of the stomach with a 16-gauge catheter-over-the-needle device inserted into the second intercostal space in the midclavicular line and then removing the needle. The catheter was left in place attached to intravenous tubing with the distal end under a water seal.38 A single 16-gauge puncture of the stomach is unlikely to leak and cause pleuritis; such punctures have long been used for placement of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes. Inserting a chest tube into the stomach is not advisable because gastric fluid may leak into the pleural space. Once the tension on the stomach is relieved, it may be possible to pass the NG tube to prevent reoccurrence of the problem. The stomach, no longer tense and wedged in the chest, can twist to allow the tube to pass. Surgical correction of the condition permitting intrathoracic herniation of the stomach is the definitive treatment to prevent recurrence of tension gastrothorax.

Replacement of Nasoenteric Feeding Tubes

Indications and Contraindications

The most common indication for replacement of a feeding tube in the ED is unintentional removal of a preexisting feeding tube. In one prospective study, 38% of tubes were removed unintentionally. Although some of these tubes had fallen out or had been coughed out, more than half were pulled out by the patient.39 Tube rupture, deterioration, or clogging may also necessitate replacement. Management of a clogged or nonirrigating feeding tube is discussed in the later section on clogged feeding tubes.

Feeding Tube Site

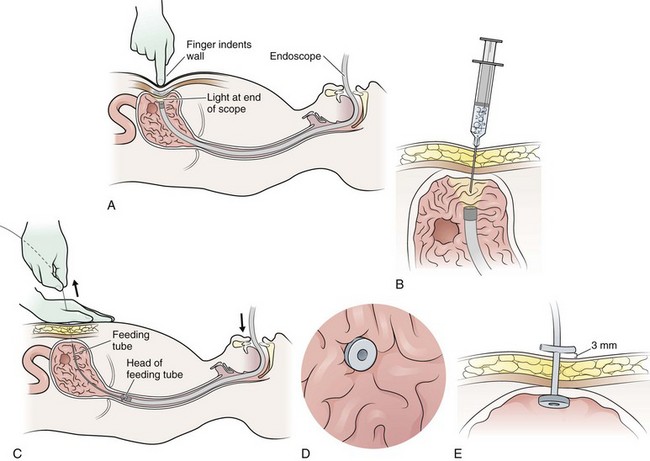

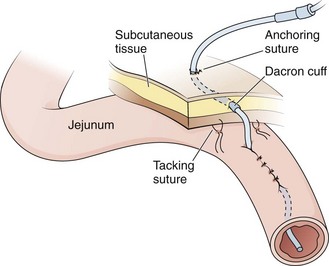

Three major classes of enteral feeding tubes are in common use and are classified according to the site of insertion. Tubes can enter through the nares (a cervical ostomy) or the abdomen (an abdominal ostomy). Enteral tubes are often categorized by the location of the tip of the tube. Tubes may terminate primarily in the stomach, such as a gastrostomy (G) or PEG tube (Fig. 40-14). They may terminate in the jejunum (J tube) (Fig 40-15) or in both the stomach and the small intestine (a PEG-J tube). To confuse the issue, some tubes enter the stomach and terminate in the stomach (G tube) or in the proximal part of the small bowel (J tube), whereas others enter the GI tract directly through the wall of the small bowel (J tube). Practically speaking, almost all gastric tubes are PEG tubes. They are placed endoscopically with local anesthesia and without a surgical incision. J tubes that enter the small bowel directly are inserted surgically under general anesthesia, require a surgical incision, and result in a surgical scar at the insertion site. Gastric feeding results in better digestion than intestinal feeding does. Jejunal feeding reduces reflux and aspiration.40 Normally, about 20% of the gastric antral contents pass into the duodenum, with 80% refluxing back into the body of the stomach for further mixing, so proximal duodenal feeding is of limited benefit in preventing aspiration.41,42 If the feeding tube is placed in the antrum of the stomach or in the small bowel, enteral feeding solution passing into the small bowel may not be tolerated and can result in diarrhea and paradoxical decreased nutrition.41,42

Confirmation of Placement

Auscultatory confirmation of tube placement can be misleading, so confirm proper placement of the tube with a radiograph before feeding.3 However, radiographic confirmation of tube placement may also be misleading. In viewing the radiograph, it is particularly important to study the area around the carina. An esophageal tube shows at most a mild change in course, whereas a tracheally placed tube usually deviates significantly as it travels into the right or left main stem bronchus. The end of an NG tube may appear to be in the stomach yet may actually be in the left lung behind and below the top of the diaphragm.43 When a stylet has been used for passage, leave it in the feeding tube for the radiograph because the tube’s course is not always visible without it. The stylets of most tubes are designed to allow insufflation and aspiration while in place. Even when stomach entry is certain, the intestinal location may be misleading on a radiograph. A nasoenteric tube may lie completely to the left of midline and yet have its tip in the duodenum, or it may occupy a position overlying the right side of the abdomen yet not have entered the duodenum. A contrast-enhanced study is necessary to ascertain duodenal position when pulmonary placement has been ruled out.44,45

The end-bulb of many nasoduodenal tubes will pass into the duodenum after positioning the patient in the right decubitus position for an hour. Some researchers recommend pretreatment with metoclopramide to enhance gastric emptying.46–48 One investigator found that metoclopramide enhances duodenal passage of nasogastrically placed feeding tubes in diabetic but not in nondiabetic patients.44 Gastric antral motility in diabetics is often impaired; metoclopramide helps restore normal synchronized activity in these patients but has little effect on emptying in subjects with normal antral function. The usual dose of metoclopramide is 10 mg administered intravenously. Also, 3 mg/kg of erythromycin lactobionate given intravenously over a 1-hour period works similarly and may be effective even if metoclopramide fails.49 Endoscopy or fluoroscopy may be necessary if positioning and metoclopramide are not successful.

Complications

Pulmonary intubation is an uncommon but well-known and potentially fatal complication of insertion of nasal feeding tubes (see Fig. 40-10A). Coughing and respiratory distress are the most common symptoms of respiratory passage of an NG tube, but there may be relatively few apparent symptoms in a demented or comatose patient.50 Decreased mentation and an absent cough reflex are predisposing factors for unrecognized nasopulmonary intubation with NG tubes.3 Misplacement is far more likely in patients with ET or tracheostomy tubes, conscious or not, perhaps because tracheal stimulation by a misplaced tube is less likely to be appreciated or communicated. A small end-bulb (e.g., 2.7 mm in diameter) can slip past a tracheal high-volume, low-pressure cuff and easily pass to the periphery of the lung.3,50–54 Pneumothorax may result when an NG tube dissects into or is withdrawn from the pulmonary parenchyma.55 Bloody aspirate from a tube should heighten awareness of possible tissue damage.

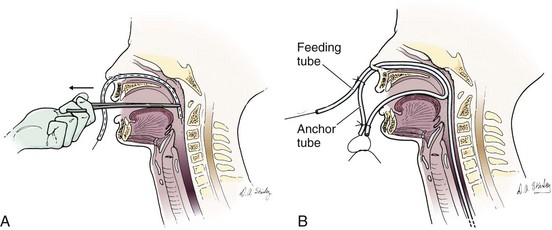

Sax and Bower recommend a technique for creating a separate NG tube anchor.56 Cut a soft weighted nasoenteric tube approximately 12 inches from the top. Pass a heavy (2-0) silk suture through the tube to exit the side hole. Insert the guidewire with care because it must not protrude from the inserted end. Sedate the patient if uncooperative. Insert the tube through the anesthetized naris into the nasopharynx, grasp it with Magill forceps, and pull to remove it through the mouth (Fig. 40-16A). Trim excess tubing without cutting the silk suture. Make a closed loop by tying the silk suture in front of the nose. Leave the loop long enough that it does not apply continuous pressure to the nose or palate while at rest. Pass the nasal feeding tube through the same nostril and secure it to the loop (Fig. 40-16B). This anchor is simpler to construct and more comfortable than anchors that pass through the opposite nostril.56

Complications of properly placed nasoenteric tubes include nasopharyngeal erosion, esophageal reflux, tracheoesophageal fistula, gagging, rupture of esophageal varices, and otitis media.57 One survey of nasogastrically fed patients found that the most distressing features of having an NG tube for feeding were deprivation of tasting, drinking, and chewing of food; soreness of the nose; rhinitis; esophagitis; mouth breathing; and the sight of other patients who were eating.58

Checking feeding tolerance is difficult with small-gauge feeding tubes. Aspiration of tubes to check for residuals is not recommended with tubes 9 Fr in size or smaller. Aspiration is likely to clog the tubes because they collapse under pressure and relatively small particles can occlude the tube. For the same reasons, the residual is likely to be inaccurate.59

Patient or Nursing Instructions

To maintain patency of the catheter, small tubes should be flushed with 20 to 30 mL of tap water at least two to three times daily and after the administration of medication.45,59 Water is a more effective irrigant than cranberry juice.60 Medications should be in liquid form or be completely dissolved or they may clog the tube. Methods of dealing with a clogged tube are discussed subsequently. The tube should be anchored to the nose and face in such a way that it is not in contact with the skin at the nasal opening. This reduces tube discomfort and prevents necrosis of the alae, nares, and distal septum. Patients who exhibit a tendency to pull on their tubes need adequate restraints. Patients receiving tube feedings should have their head elevated to at least 30 degrees above the horizontal.59

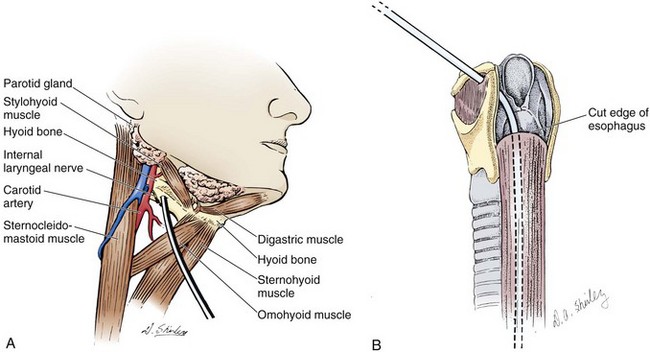

Pharyngostomy and Esophagostomy Feeding Tubes

Cervical pharyngostomy and cervical esophagostomy have both been developed relatively recently. Cervical esophagostomies are generally performed at the time of cervical or maxillofacial operations. Malignant growths in the proximal part of the esophagus, head, or neck are the primary indications for esophagostomy. Cervical esophagostomies may eventually evolve into a permanent sinus, thereby allowing the feeding tube to be removed between meals. Such tubes are unlikely to be replaced in the ED, but the concept of these feeding tubes is illustrated in Figure 40-17. Complications of pharyngostomy and esophagostomy include local soft tissue irritation, accidental extubation because of excessive length of the external tube, pulmonary aspiration from vomiting, arterial erosion with exsanguination, and esophagitis or stricture of the esophagus from reflux.

Gastroenterostomy and Jejunostomy Tubes

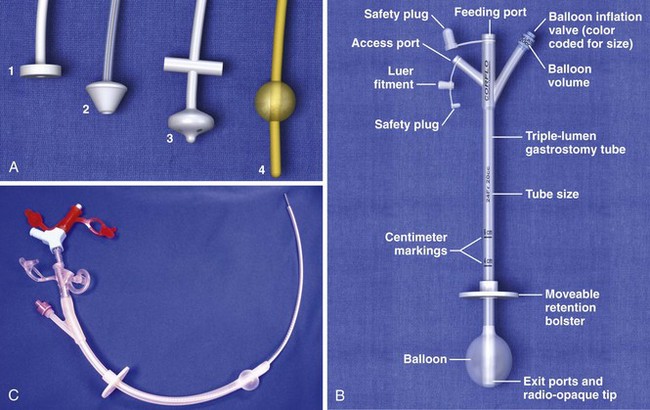

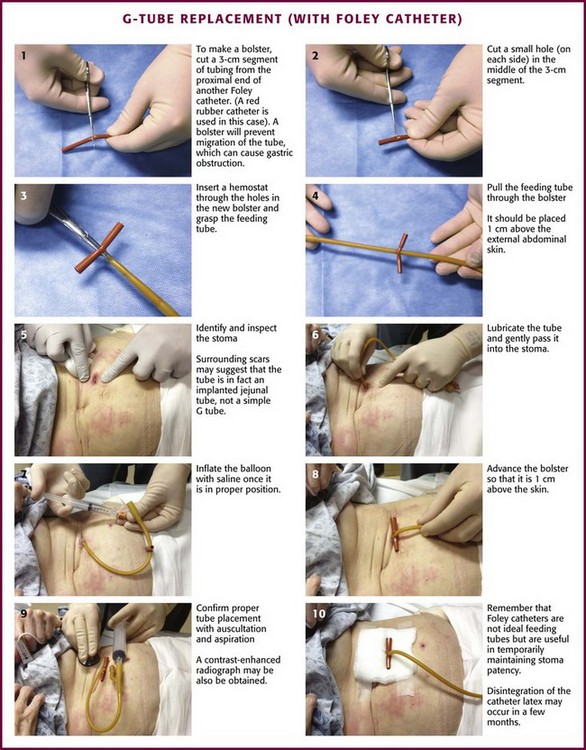

A nursing home patient with a nonfunctioning or displaced feeding tube represents a common ED scenario. The clinician cannot always determine the location of the original feeding tube by simply looking at a patient who arrives in the ED for replacement of the tube. Nevertheless, the emergency clinician should attempt to ensure that the terminal end of a replaced tube is in the same viscus as the original was. External inspection may or may not reveal where a feeding tube should terminate. Contrast-enhanced studies and fluoroscopy usually provide such information (Fig. 40-18). Gastrotomy tubes are available in various types (Fig. 40-19). Tubes are kept in place by either a modified end (such as a mushroom tip) or an inflatable balloon. A de Pezzer (mushroom) tube, a Corflo tube, or a Foley G tube is designed only for intragastric termination. Some tubes have two lumens, one terminating in the stomach for decompression and the other in the small bowel for feeding. These can be confused with tubes that have two entrances to one lumen (one for continuous feeding and the other for medications) and tubes that have a second lumen leading to an inflatable balloon. An original tube is not usually a Foley or balloon-tipped tube. An original PEG tube is pictured in Figure 40-20. Note that on cross section this original long tube has no balloon or port to inflate a balloon but has a mushroom end that is removed by traction.

Foley catheters are not ideal as long-term feeding tubes. They clog easily, and the balloon disintegrates in stomach acid. They may be used temporarily but should be replaced with specialized feeding tubes when feasible (Fig. 40-21). A call from a nursing home indicating that a tube has been pulled out should be answered by the advice that a Foley catheter be used immediately to keep the stoma open. Always inflate the balloon with saline and use a bolster to prevent migration of the tube. The clinician has a few options when faced with the task of replacing a feeding tube. Unfortunately, old records or nursing home personnel rarely give specific information that is helpful to the emergency clinician. If only a stoma exists, one may request that the nursing home describe or send the prior tube to the ED. If no surgical scar is seen at the stoma site, the tube is almost certainly a G tube or a G tube that terminated in the jejunum. When in doubt, pass a Foley catheter without balloon inflation, tape it to the skin, and refer the patient to a consultant or the original referring clinician. Some type of tube must be placed to stent the stoma, or the stoma will quickly close (in a matter of hours) and the patient might require a more complicated procedure to regain access. The only real concern of placing a gastric tube into the jejunum is that the balloon will produce intestinal obstruction if it is fully inflated.

Figure 40-21 G-tube replacement (with a Foley catheter).

If the tube is nonfunctioning yet still in place, the clinician must make a judgment regarding the risk versus benefit of removal and replacement versus an attempt at unclogging the tube (see the subsequent discussion on unclogging). The major concern is that a new tube may be misplaced (i.e., into the peritoneal cavity). If it appears that a skin incision was used to place the tube, it is unlikely that the patient has an easily removable tube. If the patient has signs of a complication (e.g., infection, ileus, intestinal obstruction), surgical consultation is warranted. Note that a migrated tube, with the balloon or tube obstructing the gastric outlet, is a common cause of gastric distention, persistent vomiting, or signs of intestinal obstruction. This is easily remedied (see procedural description in “Complications” and Fig. 40-22).

Most PEG tubes do not have sutures joining the stomach with the abdominal wall, so there is potential for a replaced tube to end up in the peritoneal cavity. Adhesions, however, usually keep the stomach appropriately positioned, but only after the tract has matured. Nonoperative tube replacement techniques are safe only through an established tract between the skin and the bowel. Catheter replacement should not be attempted in the immediate postoperative period. A simple gastrostomy takes about a week to form a tract.61 A stable tract may take 2 or 3 weeks longer to form if healing is compromised.

Poor nutrition is the most common element compromising wound healing in patients requiring a feeding tube. A Witzel tunnel may take up to 3 weeks after the operation to mature sufficiently for safe nonoperative tube replacement (see Fig. 40-15).

Equipment for Replacing a Dislodged Tube

Equipment for replacing a feeding tube through a matured site includes gloves, a stethoscope, a feeding tube, an external bolster, lubricant, a basin, and a syringe that fits the tube. Tincture of benzoin, tape, and absorbent dressing material may be used to dress the wound, although many are better left undressed.62 Some feeding tubes require special plugs or connectors. Others need to be pinched with a clamp when not in use to prevent leakage. Some tubes are placed with the aid of accompanying guidewires or stents.

The easiest tube to replace is one that has been removed in the ED or dislodged for only a few hours (Fig. 40-23). The stoma closes quite quickly, so replacement is best done as soon as possible. Gently probe the stoma site with a cotton-tipped applicator to determine patency and direction of the tract. In selected cases, a hemostat can gently dilate the opening to accept a replacement tube. Do all such attempts carefully to avoid creating a false tract. Use local anesthetic around the stoma if exploration causes pain. Bleeding is common. After the tube is passed, restrain the hands to avoid removal of the tube by uncooperative patients.

Removal of a Transabdominal Feeding Tube

A feeding tube may need to be removed because it is irreversibly clogged, leaking, or broken; persistently develops kinks; is too large or too small; causes a hypersensitivity reaction; is associated with an abscess; or is not the appropriate length for feeding into the desired viscus. Before a new transabdominal feeding tube is inserted, remove the old tube. Most, but not all tubes can be removed without endoscopy. It is imperative to know whether the tube in place is safe to remove before attempting to remove it. Standard de Pezzer or mushroom catheters that have been modified with bolsters or rings at the time of endoscopic or surgical insertion may no longer be safe to remove with traction. Tubes are occasionally secured with sutures or rigid internal bumpers or stays. It is rare, however, to encounter a tube that cannot be removed with traction/countertraction. Modest force may be required. Use a hand for countertraction, and be prepared for a pop and splattering of gastric contents (Fig. 40-24). This causes the tube and end mushroom to narrow, and the tube should come out easily. The inner crossbar, if present, may remain in the stomach when the rest of the feeding tube complex is removed by traction. The crossbar will pass in stool, and obstruction from it has yet to be reported in adults. In small children, obstruction is a possibility, and the crossbar should be removed by endoscopy.63,64

A simple Foley catheter G tube is the easiest to remove. Deflate the Foley balloon and the tube should slide right out. If the Foley balloon cannot be deflated, cut the tube to allow the balloon to deflate. Do not cut the catheter so close to the abdomen that it will be impossible to maintain a grip on it for removal by traction if the balloon still does not deflate. The balloon may also be punctured to cause it to deflate. To puncture a Foley balloon, apply traction on the catheter to draw the balloon up against the ostomy (Fig. 40-25). Using the taut feeding tube as a guide, pass a small-gauge needle along the tube to puncture the balloon. It may be necessary to try again on the other side of the catheter because the balloon may be inflated asymmetrically and contact with the needle may be established on one side and not the other. Be careful to not track away from the ostomy into the patient’s abdominal wall or to cause separate punctures of the stomach. Allow a minute for the balloon to deflate before making another attempt at removal by traction. Large, nondeflating balloons should probably be punctured, whereas small balloons may be removed with traction.

If it is not possible to pull the inner bolster or mushroom out through the ostomy, cut the tube at the skin, push the remaining short stump into the stomach, and rely on later rectal passage. Although obstruction or impaction is infrequent, it can occur, and this alternative has the potential to be problematic in children or patients who have had previous impaction, potential for bowel obstruction, or stool-passing problems. Rigid or large internal mushrooms and bolsters, the very kind that cause the most difficulty with percutaneous removal, are also more likely to cause difficulty with rectal passage. In no case should a device be released into the gut with a long length of tubing attached. Remember that double-part tubes may have an additional length of tubing for duodenal or jejunal feeding that extends far past the inner bolster. Korula and Harma reported successful intestinal elimination of 63 of 64 gastrostomy tubes that were cut at the skin entrance and advanced into the stomach through the stoma.65 These cases included tubes with internal bumpers, and success occurred regardless of the nature of the patient’s underlying medical disorder, age, or method of original tube placement. However, no patient had suspected obstruction or potential for obstruction (e.g., no previous radiotherapy, inflammatory bowel disease). The one lodged tube required endoscopic removal from the pylorus. In most cases, passage of the tube was documented by sequential radiographs, with a mean interval of 24 days until passage (range, 4 to 181 days).

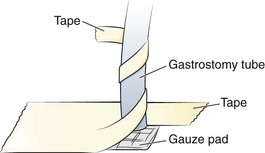

Securing a Transabdominal Feeding Tube

If a bolster is used, no additional means of securing the tube is necessary if the patient is not prone to pulling it out. Some clinicians tape tubes to the skin rather than using a bolster or use special adhesive devices designed to control the tube and prevent ingress, such as the Drain/Tube Attachment Device (Hollister, Inc., Libertyville, IL) or Flexi-Trak (ConvaTec, Skillman, NJ). Tape is particularly vulnerable to problems because the stress that the tape places on the skin as the tube pulls on the tape can lead to skin damage. Strong adhesive tape can also damage the skin on removal. Tape that is not sufficiently adhesive can let go, particularly if it gets wet. Because tape is less durable, home or nursing home caregivers who are less skilled may retape the tube (Fig. 40-26). If the tape is replaced at home, it may be placed under too much tension and cause thinning of the abdominal wall at the stoma. If too much slack is allowed, the tube may get pulled in. Strong tape can also damage the tube during tape changes if it comes to adhere too strongly to the tube. Special adhesive devices or bolsters are preferred.

Verification of Placement

There is no universally agreed-on standard with regard to performing a confirmatory contrast-enhanced study for all easily replaced feeding tubes. Some clinicians verify position routinely with a contrast-enhanced radiograph, whereas others use the clinical criteria outlined earlier. The authors advocate radiographic verification in the majority of cases, a procedure easily performed and interpreted in the ED. Routine use of postplacement contrast-enhanced radiography to confirm proper placement should be mandatory when the tube tract is immature (i.e., <1-month duration),66 when passage of the replacement catheter has been difficult, when the clinician is unable to aspirate intestinal contents, or when the patient is unable to communicate any symptoms that might occur with tube misplacement. Peritoneal infusion of feeding solution can be fatal.

Correct tube placement is easy and readily verified radiographically with a small amount of contrast material passed into the tube (Fig. 40-27). Use a catheter-tipped syringe to introduce water-soluble contrast solution (e.g., diatrizoate meglumine–diatrizoate sodium [Gastrografin]) into the tube. Barium is contraindicated because of the potential for peritoneal contamination. Inject 20 to 30 mL of water-soluble solution to document the intraluminal tube position. Take a supine abdominal film 1 to 2 minutes after instillation of dye to optimize visualization of the gut. Because the film must be obtained quickly, it is easiest to perform the injection in the radiology suite, followed by a radiograph in only a few minutes. If the contrast material does not flow freely into the tube, the procedure should be terminated immediately and the position of the tube questioned. With proper positioning, contrast material will outline the part of the gut containing the tube (e.g., stomach with a G tube). An irregular or rounded blotch with wispy edges or streamers suggests peritoneal leakage. In questionable cases, injection of dye can be performed under fluoroscopy.

Complications

Viscus puncture, viscus–abdominal wall separation, and creation of a false tract with subsequent misplacement of the tube are risks associated with dilation procedures. Complications of gastrostomy include wound infection around the catheter, performance of an unnecessary laparotomy for suspected leakage, gastrocolic fistula, pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis, bowel obstruction, peritonitis, and hemorrhage.64 Jejunostomies can cause most of these complications, as well as other types of fistulas and small bowel obstruction from adhesions or volvulus around the jejunostomy site.48,67 The most common complications of gastrostomy and gastroenterostomy are local skin erosion from leakage, wound infection, hemorrhage, and dislodgment of the tube.59 Peritonitis and aspiration are the most critical complications of gastrostomy feedings.59,67 Jejunostomies are less prone to stomal leakage and cause less nausea, vomiting, bloating, and aspiration than do gastrostomies.68,69

Dislodgment of G and J tubes is most common in the 2 weeks after creation of the ostomy.70 Extrusion of the G tube is usually caused by excessive tension applied to the tube. Only gentle contact of the gastric and abdominal walls is desirable. Uncooperative patients should be restrained, and mittens are often particularly helpful. Sutures and large mushrooms or balloons do not prevent purposeful removal of the G tube by an uncooperative patient.

A small amount of drainage is to be expected at the tube entry site. Local leakage of gastric juices may macerate and irritate the skin, which can predispose the site to local infections and abscesses and encourage the development of small granulomas.68,71 Granulomas are particularly common in children. They can be treated with silver nitrate at the time of dressing changes. Any dressing used around the entry site of an enteral nutrition tube should absorb fluid and not encourage persistent moisture.62 An unusually large stoma may promote a leak. Although insertion of a larger tube or firmer traction on the tube might be transiently effective, these measures often result in further enlargement of the stoma. Rigid gastrostomies promote leakage by widening the stoma as they pivot. Insertion of a soft, pliant feeding tube through the widened stoma is often easy and allows later contraction of the stoma.1 If these techniques are ineffective, temporary removal of the feeding tube may allow the stoma to shrink. Large amounts of drainage around the stoma site may occur with high residual volumes.72 The residual should be checked and feedings withheld until residuals are less than 100 mL. Feeding residuals should be checked every 4 hours when a patient is receiving continuous-drip feeding.73

Pneumoperitoneum after percutaneous gastrostomy is neither unusual nor dangerous. Benign pneumoperitoneum may be present as long as 5 weeks after PEG.64,72 Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis can occur through the defect in the bowel wall created for the enterostomy tube. Though often clinically insignificant, its occurrence suggests air under pressure in the small bowel. NG suction and diet change generally permit resolution of the problem. Catheter or feeding tube removal is not usually required.74

Clinically significant pulmonary aspiration can occur with G-tube feeding. Methods of checking for silent pulmonary aspiration include assessing tracheal aspirates with a glucose oxidant reagent strip or placing methylene blue in the formula and monitoring tracheal aspirates for pigmentation.57,75,76

A Foley balloon accidentally inflated in the small bowel or esophagus can lead to perforation or obstruction.77 Carefully inflate the balloon soon after it has entered the stomach to prevent perforation of the viscus. A G tube may migrate in the stomach and obstruct the gastric outlet. This complication is manifested clinically by vomiting and high residuals of feeding solution. Volvulus and jaundice may also occur as a result of balloon migration. To correct inward migration, first deflate the balloon. Pull the tube back just deep to its final position. Reinflate the balloon and pull it the rest of the way back into position.29 The external bolster should be repositioned or one made and positioned, or inward migration will probably reoccur.63,72 If the balloon is not deflated before repositioning, the bowel in which it is wedged may be drawn back with it, thereby preventing relief of the obstruction and possibly precipitating intussusception.

Clogged Feeding Tubes

Clogging, leaking, fracture, and kinking are problems common to all feeding tubes. Whenever feasible, replace nonfunctioning or leaking tubes with new ones. Although it may be only a temporary solution, it is prudent to attempt to unclog a tube before it is replaced, especially if the tube has a complex placement or the clinician is unsure how the tube is secured internally. Large G tubes are the least likely to clog. G tubes at least 28 Fr in size can tolerate home blenderized foods and viscous feeding solutions. Isosmotic feeding solutions are tolerated by fairly narrow tubes and cost one sixth of what elemental feedings cost. Isosmotic feedings will clog needle catheters.46 When tube lumens are 14 Fr or smaller, all pills and the contents of all capsules should be dissolved in water to prevent obstruction of the tube.62

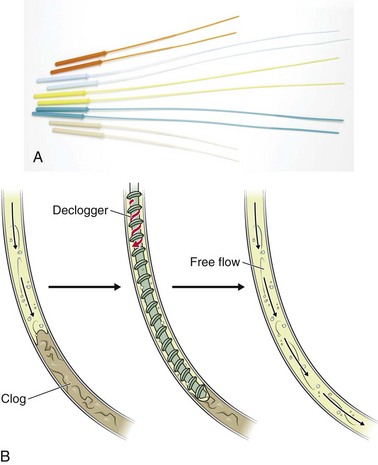

Accumulated feeding solution or medication precipitates are very difficult to clean or remove. Milking a pliant tube backward may remove some of the cheesy precipitates. Guidewires or stylets may clear the proximal portion of a clogged tube lumen but are unsafe to use in subcutaneous areas of the lumen because they can puncture the tube and injure the patient or create a leak in the tube. Bionix Medical Technologies supplies tube decloggers in two lengths and several diameters for clearing clogs in G and J tube (Fig. 40-28). After selecting a declogger shorter than the feeding tube, insert it gently into the tube until the end of the screw hits the clog and then rotate it clockwise to bury the end in the clog. Next, slide the declogger up and down to break up and dislodge the clog. Insertion, rotation, and sliding might have to be repeated several times until the dislodged material can be flushed into the patient with saline or water. Gravity alone should be sufficient to allow fluid to pass through the feeding tube into the patient and is a better test of successful declogging than is passage of fluid with a syringe. Theoretically, the pointed screw end of the declogger can puncture the tube, or if a declogger is put in that is too long, it may puncture the bowel or stomach directly. According to the company, no cases have been reported.

Figure 40-28 A and B, The Bionix tube declogger. Note: Two lengths and several diameters are available. Caution must be observed any time that the screw end of the declogger passes from view because the potential exists to extend or puncture out of the tube and into the patient. (A and B, Redrawn courtesy of Bionix Medical Technologies. Bionix Enteral Feeding DeCloggers are a registered trademark of Bionix Medical Technologies. www.BionixMed.com. Accessed June 21, 2012.)

Fogarty arterial embolectomy catheters can be used to unclog J and G tubes.78 Insert the soft tip of the Fogarty catheter into the feeding tube and advance it while monitoring the insertion distance to avoid penetrating farther than the length of the feeding tube. Premeasure the allowable length of insertion. A No. 4 embolectomy catheter is suitable for a 10- or 12-Fr feeding tube, and a No. 5 embolectomy catheter is suitable for a 14-Fr feeding tube. When the catheter meets an obstruction, inflate the balloon. This usually opens the obstruction sufficiently for passage of the catheter. Once the Fogarty has been manipulated to a point just proximal to the internal feeding opening, withdraw it while gently inflating and deflating the balloon intermittently. Do not withdraw the catheter while the balloon is inflated because the catheter and feeding tube tend to move as a unit. Repeat this procedure several times if necessary. Once declogging is successful, inject contrast material to confirm the position and integrity of the tube.78

Irrigation with carbonated beverages and high-pressure irrigation with small-volume syringes have also been recommended as techniques for unclogging feeding tubes. Although irrigation seems like a straightforward and simple solution, these techniques are generally ineffective; furthermore, the possibility exists for dangerous tube rupture with internal leakage. Broviac catheters are especially prone to tube aneurysms, which can rupture under pressure.71 Tubes unclogged by forceful irrigation or by deep luminal probing should be radiographed after injection of contrast material to check the integrity of the tube.

References

1. Gauderer, MWL. Methods of gastrostomy tube replacement. In: Ponsky JL, ed. Techniques of Percutaneous Gastrostomy. New York: Igaku-Shoin Medical; 1988:79.

2. Gordon, AM, Jr. Enteral nutritional support. Postgrad Med. 1981;70:155.

3. Sweatman, AJ, Tomasello, PA, Loughhead, MG, et al. Misplacement of nasogastric tubes and oesophageal monitoring devices. Br J Anaesth. 1978;50:389.

4. Huang, ES, Karsan, S, Kanwal, F, et al. Impact of nasogastric lavage on outcomes in acute GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:971.

5. Witting, MD. “You wanna do what?!” Modern indications for nasogastric intubation. J Emerg Med. 2007;33:61.

6. Witting, MD, Magder, L, Heins, A, et al. ED predictors of upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding in patients without hematemesis. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:280.

7. Alessi, DM, Berci, G. Aspiration and nasogastric intubation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;94:486.

8. Fuller, RK, Loveland, JP, Frankel, MH. An evaluation of the efficacy of nasogastric suction treatment in alcohol pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1981;75:349.

9. Adler, JS, Garaeb, DA, Nugent, RA. Inadvertent intracranial placement of nasogastric tube in a patient with severe head trauma. Can Med Assoc J. 1992;147:668.

10. Bryant, LR, Mobin-Uddin, K, Dillon, ML, et al. Comparison of ice water with iced saline solution for gastric lavage in gastroduodenal hemorrhage. Am J Surg. 1972;124:570.

11. Menguy, R, Masters, YF. Influence of cold on stress ulceration and on gastric mucosal blood flow and energy metabolism. Ann Surg. 1981;194:29.

12. Ponsky, JL, Hoffman, M, Swayngim, DS. Saline irrigation in gastric hemorrhage: the effect of temperature. J Surg Res. 1980;28:204.

13. Larson, DE, Farnell, MB. Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Mayo Clin Proc. 1983;58:371.

14. Andrus, CH, Ponsky, JL. The effects of irrigant temperature in upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a requiem for iced saline lavage. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:1062.

15. Coffin, B, Pocard, M, Panis, Y, et al. Erythromycin improves the quality of EGD in patients with acute upper GI bleeding: a randomized controlled study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:174.

16. Frossard, JL, Spahr, L, Queneau, PE, et al. Erythromycin intravenous bolus infusion in acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a randomized, controlled, double-blind trial. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:17.

17. Volden, C, Grinde, J, Carl, D. Taking the trauma out of nasogastric intubation. Nursing. 1980;10:64.

18. Eisenberg, PG. Nasoenteral tubes. RN. 1994;57:62.

19. Wolfe, TR, Fosnocht, DE, Linscott, MS. Atomized lidocaine as topical anesthesia for nasogastric tube placement: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35:421.

20. Spektor, M, Kaplan, J, Kelley, J, et al. Nebulized or sprayed lidocaine as anesthesia for nasogastric intubations. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:406.

21. Cullen, L, Taylor, D, Taylor, S, et al. Nebulized lidocaine decreases the discomfort of nasogastric tube insertion: a randomized, double-blind trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:131.

22. Singer, AJ, Konia, N. Comparison of topical anesthetics and vasoconstrictors vs. lubricants prior to nasogastric intubation: a randomized, controlled trial. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:184.

23. Labedski, L, Scavone, JM, Ochs, HR, et al. Reduced systemic absorption of intrabronchial lidocaine by high frequency nebulization. J Clin Pharmacol. 1990;30:785.

24. Collins, JF. Methemoglobinemia as a complication of 20% benzocaine spray for endoscopy. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:211.

25. Gupta, D, Agarwal, A, Nath, SS, et al. Inflation with air via a facepiece for facilitating insertion of a nasogastric tube: a prospective, randomised, double-blind study. Anaesthesia. 2007;62:127.

26. May, M, Nellis, KJ. Nasogastric intubation: avoiding complications. Res Staff Physician. 1984;30:60.

27. Metheny, N, McSweeney, L, Wehrle, MA, et al. Effectiveness of the auscultatory method in predicting feeding tube location. Nurs Res. 1990;39:262.

28. Metheny, N, Reed, L, Wiersema, L, et al. Effectiveness of pH measurements in predicting feeding tube placement: an update. Nurs Res. 1993;42:324.

29. Gilbertson, HR, Rogers, EJ, Ukoumunne, OC. Determination of a practical pH cutoff level for reliable confirmation of nasogastric tube placement. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2011;35:540.

30. Metheny, N. Measures to test placement of nasogastric and nasointestinal feeding tubes: a review. Nurs Res. 1988;37:324.

31. Cohen, DD, Fox, RM. Nasogastric intubation in the anesthetized patient. Anesth Analg. 1963;42:578.

32. Siegel, IB, Kahn, RC. Insertion of difficult nasogastric tubes through a nasoesophageally placed endotracheal tube. Crit Care Med. 1987;15:876.

33. Sprague, DH, Carter, SR. An alternate method for nasogastric tube insertion. Anesthesiology. 1980;53:436.

34. Rosenberg, H. The difficult nasogastric intubation: tips and techniques. Emerg Med. 1988;20:95.

35. Roberts, JR, Halstead, J. Passage of a nasogastric tube in an intubated patient facilitated by a video laryngoscope. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:330.

36. Ohn, KC, Wu, WH. A new method for nasogastric tube insertion. Anesthesiology. 1979;51:568.

37. Lee, TS, Wright, BD. Flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope for difficult nasogastric intubation. Anesth Analg. 1981;60:904.

38. Slater, RG. Tension gastrothorax complicating acute traumatic diaphragmatic rupture. J Emerg Med. 1992;10:25.

39. Jeffers, SL, Dorn, LA, Meguid, MM. Mechanical complications of enteral nutrition: prospective study of 109 consecutive patients. Clin Res. 1984;32:233.

40. Silk, DBA. The evolving role of post–ligament of Treitz nasojejunal feeding in enteral nutrition and the need for improved feeding tube design and placement methods. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2011;35:303.

41. Hanson, RL. Predictive criteria for length of nasogastric tube insertion for tube feeding. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1977;3:160.

42. Ellett, M, Beckstrand, J, Welch, J, et al. Predicting the distance for gavage tube placement in children. Pediatr Nurs. 1992;18:119.

43. Woodall, BH, Winfield, DF, Bisset, GS, III. Inadvertent tracheobronchial placement of feeding tubes. Radiology. 1987;165:727.

44. Kittinger, JW, Sandler, RS, Heizer, WD. Efficacy of metoclopramide as an adjunct to duodenal placement of small-bore feeding tubes: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1987;11:33.

45. Stogdill, BJ, Page, CP, Pestana, C. Nonoperative replacement of a jejunostomy feeding catheter. Am J Surg. 1984;147:280.

46. Hinsdale, JG, Lipkowitz, GS, Pollock, TW, et al. Prolonged enteral nutrition in malnourished patients with non-elemental feeding. Am J Surg. 1985;149:334.

47. Christie, DL, Ament, ME. A double blind cross-over study of metoclopramide v. placebo for facilitating passage of multipurpose biopsy tube. Gastroenterology. 1976;71:726.

48. Rombeau, JL, Twomey, PL, McLean, GK, et al. Experience with a new gastrostomy-jejunal feeding tube. Surgery. 1983;93:574.

49. Di Lorenzo, C, Lachman, R, Hyman, PE. Intravenous erythromycin for postpyloric intubation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1990;11:45.

50. Lipman, TO, Kessler, T, Arabian, A. Nasopulmonary intubation with feeding tubes: case reports and review of the literature. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1985;9:618.

51. Halloran, O, Grecu, B, Sinha, A. Methods and complications of nasoenteral intubation. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2011;35:61.

52. Dorsey, JS, Cogordan, J. Nasotracheal intubation and pulmonary parenchymal perforation. Chest. 1985;87:131.

53. Marderstein, EL, Simmons, RL, Ochoa, JB. Patient safety: effect of institutional protocols on adverse events related to feeding tube placement in the critically ill. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:39.

54. Sparks, DA, Chase, DM, Coughlin, LM, et al. Pulmonary complications of 9931 narrow-bore nasoenteric tubes during blind placement: a critical review. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2011;35:625.

55. Roubenoff, R, Ravich, WJ. Pneumothorax due to nasogastric feeding tubes: report of four cases, review of the literature, and recommendations for prevention. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:184.

56. Sax, HC, Bower, RH. A method for securing nasogastric tubes in uncooperative patients. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1987;164:471.

57. Korda, MJ, Guenter, P, Rombeau, JL. Enteral nutrition in the critically ill. Crit Care Clin. 1987;3:133.

58. Padilla, GV, Grant, M, Wong, H, et al. Subjective distresses of nasogastric tube feeding. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1979;3:53.

59. Cataldi-Betcher, EL, Seltzer, MH, Slocum, BA, et al. Complications occurring during enteral nutrition support: a prospective study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1983;7:546.

60. Wilson, MF, Haynes-Johnson, V. Cranberry juice or water? A comparison of feeding-tube irrigants. Nutr Support Serv. 1987;7:23.

61. Locker, DL, Foster, JE, Craun, ML, et al. A technique for long-term continent gastrostomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1985;160:73.

62. Bruckstein, AH. Managing the percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube. Postgrad Med. 1987;82:143.

63. Gauderer, MWL. Techniques of surgical gastrostomy. In: Ponsky JL, ed. Techniques of Percutaneous Gastrostomy. New York: Igaku-Shoin Medical; 1988. [9].

64. Ponsky, JL, Gaudere, MWL, Stellato, TA, et al. Percutaneous approaches to enteral alimentation. Am J Surg. 1985;149:102.

65. Korula, J, Harma, C. A simple and inexpensive method of removal or replacement of gastrostomy tubes. JAMA. 1991;265:1426.

66. Taheri, MR, Singh, H, Duerksen, DR. Peritonitis after gastrostomy tube replacement: case series and review of literature. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2011;35:56.

67. Torosian, MH, Rohbeau, JL. Feeding by tube enterostomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1980;150:918.

68. Meguid, MM, Eldor, S, Ashe, W. The delivery of nutritional support: a potpourri of new devices and methods. Cancer. 1985;55:279.

69. Heymsfield, SB, Horowitz, J, Lawson, DH. Enteral hyperalimentation. In: Berk JE, ed. Developments in Digestive Diseases. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1980:282.

70. Ciocon, JO, Silverstone, FA, Graves, LM, et al. Tube feedings in elderly patients. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:429.

71. Boland, MP, Patrick, J, Stoski, DS, et al. Permanent enteral feeding in cystic fibrosis: advantages of a replaceable jejunostomy tube. J Pediatr Surg. 1987;22:843.

72. Kaufman, Z, Schpitz, B, Dinbar, A. Reinsertion of a catheter for feeding jejunostomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1984;158:292.

73. Abbott, WC, Echenique, MM, Bisman, BR, et al. Nutritional care of the trauma patient. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1983;157:585.

74. Cogbill, TH, Wolfson, RH, Moore, EE, et al. Massive pneumatosis intestinalis and subcutaneous emphysema: complication of needle catheter jejunostomy. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1983;7:171.

75. Winterbauer, RH, Durning, RB, Barron, E, et al. Aspirated nasogastric feeding solution detected by glucose strips. Ann Intern Med. 1981;95:67.

76. Trebar, DM, Stechmiller, J. Pulmonary aspiration in tube-fed patients with artificial airways. Heart Lung. 1984;13:667.

77. Chester, JF, Turnbull, AR. Intestinal obstruction by overdistension of a jejunostomy catheter balloon: a salutary lesson. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1988;12:410.

78. Bentz, ML, Tollett, CA, Dempsey, DT. Obstructed feeding jejunostomy tube: a new method of salvage. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1988;12:417.