38 Myoclonus

There are various classifications of myoclonus; these include (1) etiology (Table 38-1), (2) affected body region (focal, segmental, multifocal, or generalized forms), (3) the presence or absence of specific provocative factors, and (4) specific site of nervous system origin of the abnormal neuronal discharges (Table 38-2). Spontaneous myoclonus has no clinically identifiable mechanism. Reflex myoclonus occurs in response to specific external sensory stimuli. Voluntary movement or attempts to perform specific movements induce action or intention myoclonus.

Table 38-1 Etiologies of Pathologic Myoclonus

| Type of Myoclonus | Etiologies |

|---|---|

| Essential | Autosomal dominant trait with reduced penetrance and variable expressivity |

| Myoclonic epilepsy | Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, benign myoclonus of infancy |

| Secondary | Brain trauma, infection, inflammation (encephalitis, Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease), tumors (neoplasms), or cerebral hypoxia due to temporary lack of oxygen (i.e., posthypoxic myoclonus or Lance–Adams syndrome) |

| Spinal | Spinal cord trauma, infection, inflammation, or lesions may produce segmental myoclonus |

| Inborn biochemical errors | Inborn errors of metabolism (lysosomal storage diseases: Tay–Sachs disease, Sandhoff disease, sialidosis) |

| Infectious | Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease |

| Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) | |

| Whipple disease (facial myoclonus—oculofacial masticatory monorhythmia) | |

| Neuroimmunologic | Stiffman variant: Encephalomyelitis with rigidity |

| Neurodegenerative | Parkinsonism, Huntington disease, Alzheimer disease, Lafora disease, corticobasal degeneration, progressive supranuclear palsy, or olivopontocerebellar atrophy |

| Metabolic | Metabolic conditions, such as kidney, liver, or respiratory failure, hypokalemia, hyperglycemia, etc. |

| Mitochondrial | Mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, particularly MERFF syndrome (myoclonus epilepsy with ragged-red fibers), or other progressive myoclonic encephalopathies, including those characterized by epilepsy and dementia (e.g., Lafora disease) or epilepsy and ataxia (e.g., Unverricht–Lundborg disease) |

| Medications: Drug-induced myoclonus | Serotonin receptor inhibitors: serotonin syndrome; toxic levels of anticonvulsants, levodopa, and certain antipsychotic agents (tardive myoclonus) |

| Toxins | Exposure to toxic agents, such as bismuth or other metals |

Table 38-2 Classification of Myoclonus

| Classification Bases | Classifications |

|---|---|

| Affected body part | |

| Provoking symptom | |

| Neurophysiology | |

| Etiology | |

| Additional forms |

Clinical Presentation

Pathologic Myoclonus

It is essential to distinguish the various forms of presumed pathologic myoclonus (Table 38-1).

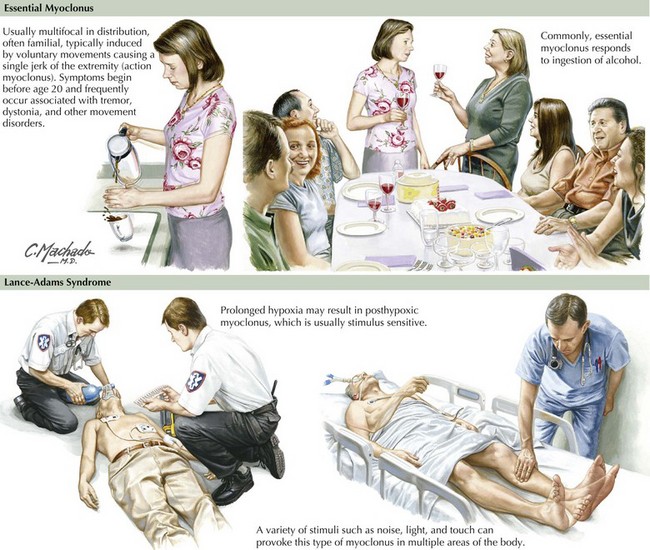

Essential myoclonus is an isolated neurologic finding that has no association with seizures, dementia, or ataxia. It is nonprogressive, usually multifocal in distribution, typically induced by voluntary movements (action myoclonus), and usually responds to alcohol (Fig. 38-1).

Any underlying disease process or cause of CNS dysfunction may lead to secondary myoclonus (Fig. 38-1).

Caviness JN. Myoclonus. Parkinsonism & related disorders. 2007;13(Suppl. 3)):S375-S384.

Gordon MF. Toxin and drug-induced myoclonus. Adv Neurol. 2002;89:49-76.

Hallet M. Neurophysiology of brainstem myoclonus. Adv Neurol. 2002;89:99-102.

Obeso JA. Therapy of myoclonus. Clin Neurosci. 1995-1996;3:253-257.

Rubboli G, Tassinari CA. Negative Myoclonus. An overview of its clinical features, pathophysiological mechanism, and management. Nerurophysiol Clin. 2006 Sep-Dec;36(5-6):337-343. Epub 2007 Jan 23

Shafiq M, Lang AE. Myoclonus in parkinsonian disorders. Adv Neurol. 2002;89:77-83.

Watts RL, Koller WC, editors. Movement Disorders: Neurologic Principles and Practice. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc, 1997.