Mycosis fungoides

Diagnosis and staging

Revisions to the staging and classification of mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the cutaneous lymphoma task force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC).

Olsen E, Vonderheid E, Pimpinelli N, Willemze R, Kim Y, Knobler R, et al. Blood 2007; 110: 1713–22.

Natural history

Specific investigations

Adequate skin biopsy with histology to be reviewed by a pathologist expert in cutaneous lymphoma. Immunophenotype, and TCR gene analysis are recommended but not essential

Adequate skin biopsy with histology to be reviewed by a pathologist expert in cutaneous lymphoma. Immunophenotype, and TCR gene analysis are recommended but not essential

A complete physical examination, with assessment of percentage body surface area and pruritus

A complete physical examination, with assessment of percentage body surface area and pruritus

Comprehensive metabolic panel, LDH, hematology, differential white blood cell count, Sézary cell count (if available) or peripheral blood flow cytometry (preferred), and TCR gene analysis if flow is abnormal or SS is suspected

Comprehensive metabolic panel, LDH, hematology, differential white blood cell count, Sézary cell count (if available) or peripheral blood flow cytometry (preferred), and TCR gene analysis if flow is abnormal or SS is suspected

Imaging with CT or PET/CT scans is suggested in patients with tumor lesions and palpable lymph nodes

Imaging with CT or PET/CT scans is suggested in patients with tumor lesions and palpable lymph nodes

Lymph node biopsy with histology, immunophenotype, and TCR gene analysis, if palpable lymph nodes are noted

Lymph node biopsy with histology, immunophenotype, and TCR gene analysis, if palpable lymph nodes are noted

Emollients

Emollients Topical corticosteroids

Topical corticosteroids UVB or PUVA

UVB or PUVA Topical chemotherapy

Topical chemotherapy Local radiotherapy

Local radiotherapy Topical bexarotene and other retinoids

Topical bexarotene and other retinoids Oral bexarotene and other retinoids

Oral bexarotene and other retinoids Interferons

Interferons Denileukin diftitox

Denileukin diftitox Extracorporeal photopheresis

Extracorporeal photopheresis Low-dose methotrexate

Low-dose methotrexate PUVA ± retinoids

PUVA ± retinoids PUVA ± interferons

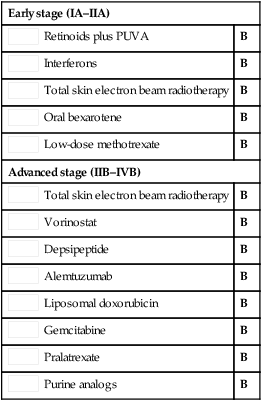

PUVA ± interferons Retinoids plus PUVA

Retinoids plus PUVA Interferons

Interferons Total skin electron beam radiotherapy

Total skin electron beam radiotherapy Oral bexarotene

Oral bexarotene Low-dose methotrexate

Low-dose methotrexate Total skin electron beam radiotherapy

Total skin electron beam radiotherapy Vorinostat

Vorinostat Depsipeptide

Depsipeptide Alemtuzumab

Alemtuzumab Liposomal doxorubicin

Liposomal doxorubicin Gemcitabine

Gemcitabine Pralatrexate

Pralatrexate Purine analogs

Purine analogs

Clinical trials

Clinical trials Topical bexarotene gel and other retinoids

Topical bexarotene gel and other retinoids Single-agent chemotherapy

Single-agent chemotherapy Combination chemotherapy

Combination chemotherapy Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation

Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation Liposomal doxorubicin

Liposomal doxorubicin Gemcitabine

Gemcitabine Pralatrexate

Pralatrexate Purine analogs

Purine analogs