62

Mycobacterial Diseases

Key Points

• Mycobacteria are the etiologic agents of three major types of infection:

– Leprosy – Mycobacterium leprae.

– Tuberculosis – Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

– Atypical or nontuberculous infections – e.g. Mycobacterium marinum, Mycobacterium chelonae (Tables 62.1 and 62.2).

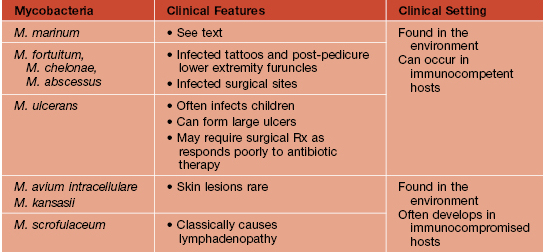

Table 62.1

Mycobacteria that cause cutaneous disease.

| Group and Pigment | Rate of Growth | Examples of Pathogens |

| Slow growers | ||

| Photochromogens* | 2–3 weeks | M. kansasii, M. marinum, M. simiae |

| Scotochromogens† | 2–3 weeks | M. scrofulaceum, M. szulgai, M. gordonae, M. xenopi |

| Nonchromogens‡ | 2–3 weeks | M. tuberculosis, M. avium, M. intracellulare, M. ulcerans, M. haemophilum, M. bovis§ |

| Rapid growers | 3–5 days | M. fortuitum, M. chelonae, M. abscessus |

| Noncultured (to date) | M. leprae |

* Capable of yellow pigment formation upon exposure to light.

† Capable of yellow pigment production without light exposure.

‡ Incapable of pigment production.

§ Including bacillus Calmette–Guérin.

Modified classification of Runyon from Hautmann G, Lotti T. Atypical mycobacterial infections of the skin. Dermatol. Clin. 1994;12:657–668; Yates VM, Rook GAW. Mycobacterial infections. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C (eds). Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology, 7 edn. London: Blackwell Science, 2004;28.1–39; Neves RG, Pradinaud R. Micobacterioses atípicas. In: Neves RG, Talhari S (eds). Dermatologia Tropical. Rio de Janeiro: Medsi, 1995:283–290.

Table 62.2

Important features of atypical mycobacteria.

Disseminated skin lesions are an HIV-defining criterion, most commonly due to M. avium intracellulare or M. kansasii.

Leprosy

• Slowly progressive disease characterized by granuloma formation in nerves and the skin.

• Affects all ages, but bimodal peak distribution – ages 10–15 years and 30–60 years.

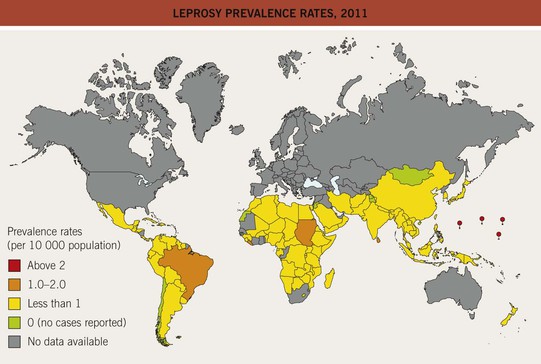

• Currently, the highest incidence is in Brazil (Fig. 62.1).

Fig. 62.1 Leprosy prevalence rates, 2011. The World Health Organization (WHO) has achieved its goal of a prevalence rate of less than 1 case per 10 000 persons in all but a few countries. Reproduced from the World Health Organization, http://www.who.int/lep/situation/prevalence/en.

• Incubation period averages 4–10 years.

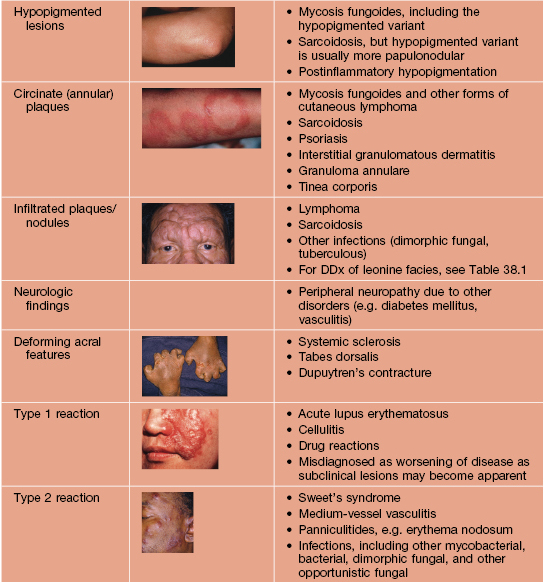

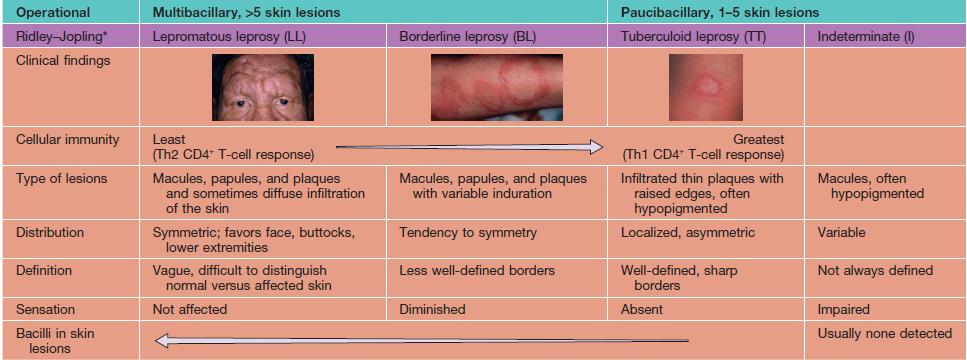

• Degree of immunity is reflected in clinical findings (Table 62.3; Figs. 62.2 and 62.3) and histopathologic features; the latter range from macrophages containing numerous bacilli (globi) in lepromatous leprosy to granulomas without organisms in tuberculoid leprosy.

Table 62.3

Classification of leprosy: Ridley–Jopling and operational.

Adapted from A Guide to Leprosy Control, 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1988;27–28.

Fig. 62.2 Tuberculoid leprosy. Note the elevated border and central hypopigmentation. Courtesy, Robert Hartman, MD.

Fig. 62.3 Lepromatous leprosy. A Note the diffuse infiltration with leonine facies and madarosis. B Numerous nodules and thick plaques on the forearms. A, B, Courtesy, Louis A. Fragola, Jr., MD.

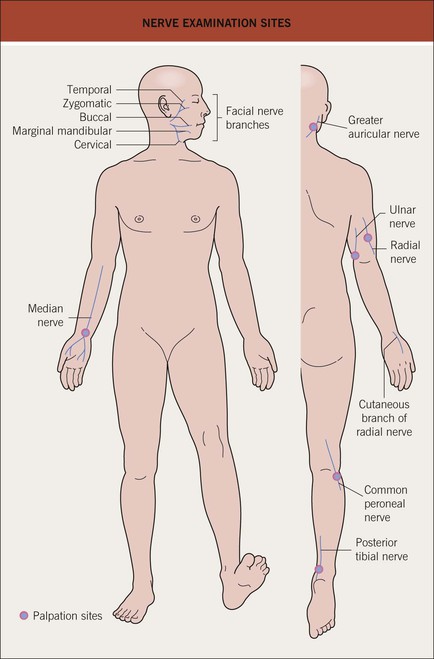

• Nerves are often affected, particularly ones close to the surface of the skin (Figs. 62.4 and 62.5); sensations of pain, temperature, and/or touch should be evaluated within skin lesions.

Fig. 62.4 Nerve examination sites.

Fig. 62.5 Leprosy. Enlargement of the radial nerve with a circumscribed area of hypopigmentation. Courtesy, Regional Dermatology Training Centre, Moshi, Tanzania.

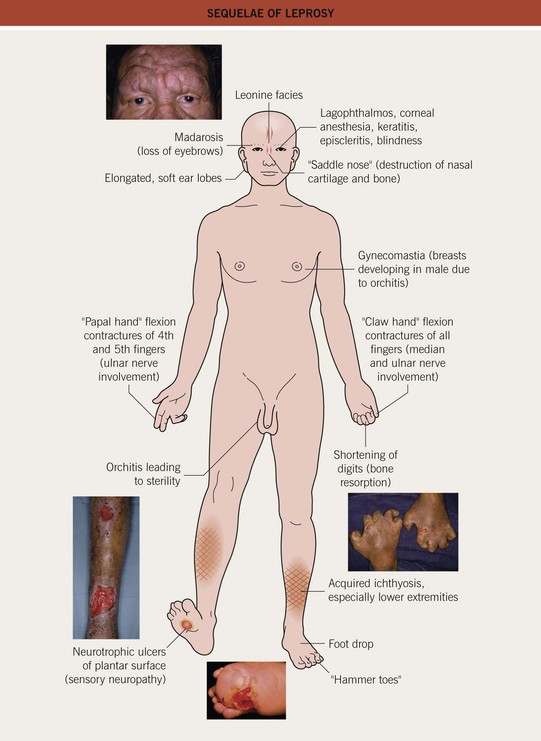

• Sequelae of leprosy can be disfiguring (Figs. 62.6 and 62.7).

Fig. 62.6 Sequelae of leprosy. A The patient has madarosis, a saddle nose, and blindness in the left eye. B Ocular involvement and bluish discoloration of affected skin due to treatment with clofazimine. A, Courtesy, Evangeline Handog, MD; B, Courtesy, Louis A. Fragola, Jr., MD.

• Reactive states that can involve the skin may develop, especially following institution of antimicrobial treatment.

– Type 1 (reversal reaction) – acute inflammation of cutaneous lesions (Fig. 62.8A) and nerves; appears rapidly due to a change in the immunologic state of the patient; in the case of upgrading, subclinical lesions can become clinically apparent.

Fig. 62.8 Leprosy reactions. A Type 1 ‘upgrading’ reaction in a patient with borderline lepromatous disease characterized by marked inflammation of a facial plaque. B Erythema nodosum leprosum (type 2 reaction) with the appearance of multiple red papulonodules as a result of immune complex-mediated small vessel vasculitis in a patient with lepromatous leprosy. B, Courtesy, Louis A. Fragola, Jr., MD.

– Type 2 (vasculitis) – formation of immune complexes in the setting of an excessive humoral immune reaction, leading to the appearance of cutaneous lesions, particularly erythema nodosum leprosum (Fig. 62.8B).

Cutaneous Tuberculosis (TB)

• Cutaneous lesions reflect mode of exposure and the degree of immunity.

• Exogenous exposure (inoculation).

– TB verrucosa cutis – secondary to inoculation in persons with moderate to high immunity to M. tuberculosis; asymptomatic, wart-like papule that gradually enlarges (Fig. 62.9); may heal spontaneously after several years.

Fig. 62.9 Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis. A wart-like papule at the site of exogenous inoculation in a patient with immunity against M. tuberculosis.

• Endogenous spread of infection.

– Some degree of cellular immunity (TST/PPD [tuberculin skin test] usually positive).

• Scrofuloderma – firm, subcutaneous nodules that become fluctuant; may ulcerate or drain via sinus tracts that heal as tethered scars; represents spread of infection from underlying disease (e.g. in bones and lymph nodes, often cervical; Fig. 62.10).

Fig. 62.10 Scrofuloderma. Plaques and nodules with central ulceration as well as resultant scarring with retraction.

• Lupus vulgaris – typically a red-brown plaque that can expand with central scar formation (Fig. 62.11); as with other granulomatous skin diseases such as sarcoidosis, pressure (diascopy) results in a yellow-brown color; represents direct extension or hematogenous/lymphatic spread of infection.

Fig. 62.11 Lupus vulgaris. A Annular granulomatous plaque with central scarring. B Two dull red-brown plaques with papular borders, scale and central clearing. C Violet-brown plaque on the neck. A, Courtesy, Marcia Ramos-e-Silva, MD; C, Courtesy, Eugene Mirrer, MD.

– Impaired cellular immunity (TST/PPD usually negative).

• Orificial TB – autoinoculation of skin or mucosa adjacent to an orifice draining an active tuberculous infection (Fig. 62.12); occurs in patients with advanced internal TB.

Fig. 62.12 Orificial tuberculosis. A nonhealing ulcer of the nasal mucosa. Courtesy, Louis A. Fragola, Jr., MD.

• Tuberculous gumma – firm subcutaneous nodule or fluctuant swelling that often ulcerates; seen in the setting of hematogenous dissemination.

• Tuberculids (cutaneous immune reactions to M. tuberculosis).

– Papulonecrotic tuberculid – widely distributed, dusky red papules or papulopustules, sometimes with central crusts; favors the extremities and may resemble PLEVA (Fig. 62.13).

– Erythema induratum, a form of panniculitis – subcutaneous nodules that may ulcerate; favors the posterior calves (see Chapter 83).

• Confirmation of diagnosis: tuberculin skin test (TST/PPD) or IFN-γ release assays (e.g. QuantiFERON-TB Gold [In-Tube]) or testing of tissue with polymerase chain reaction for M. tuberculosis DNA; advantages and disadvantages of the first two tests are outlined in Table 62.5.

Table 62.5

Advantages and disadvantages of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) release assays and tuberculin skin testing.

Both types of tests may be negative in patients with early active tuberculosis. Indeterminate IFN-γ release assay results due to failure of the internal positive control (i.e. a ‘low mitogen’ response) are more common in immunocompromised individuals and young children. Indeterminate results due to inappropriately high IFN-γ levels in the negative control (‘high nil’) can also occur. Testing with a second method after an initial negative test may be useful when the risk of infection/progression is high or when there is clinical suspicion of active tuberculosis. The QuantiFERON®-TB Gold (In-Tube) test directly measures IFN-γ levels, whereas the T-SPOT®.TB test determines the number of IFN-γ-producing T cells; both use a peripheral blood sample.

| Tuberculin Skin Test | IFN-γ Release Assays | |

| Advantages | Does not require a laboratory Relatively low cost |

Requires a single patient visit Results can be available within 24 hours Prior BCG vaccination does not cause a false-positive result Does not boost responses measured by subsequent tests |

| Disadvantages | Requires two patient visits Results not available for 48 hours Prior BCG vaccination can cause a false-positive result May boost responses in subsequent tests Infections with nontuberculous mycobacteria may lead to a false-positive result |

Requires laboratory processing within 16 hours (for QuantiFERON®-TB Gold [In-Tube]) or 8 hours (for T-SPOT®.TB; time limit of 30 hours if use T-cell Xtend®) Relatively high cost Infections with some nontuberculous mycobacteria (e.g. M. kansasii, M. szulgai, and M. marinum) may lead to a false-positive result |

| Situations where preferable | Children <5 years of age | Patient groups that historically have low rates of returning for a second visit (e.g. homeless persons, drug users) Individuals who have received BCG |

BCG, bacille Calmette–Guérin.

Atypical Mycobacteria

• Skin infections most commonly arise via traumatic inoculation; other routes include surgical or cosmetic procedures (e.g. liposuction, tattooing) and exposure to contaminated water (e.g. soaking distal lower extremities prior to pedicure; see Table 62.2).

• Clinically, pustules, plaques, or nodules develop that may become keratotic or centrally ulcerated.

• A sporotrichoid or lymphocutaneous pattern (linear arrangement of lesions along draining lymphatics) may be seen (Figs. 62.14 and 62.15).

Fig. 62.14 Complication of injection of methanol extraction residue (MER) of bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG), an attenuated strain of Mycobacterium bovis. Nodules, some of which have ulcerated, are arranged in a linear ‘lymphatic’ pattern in a patient with a high-risk extremity melanoma who had received an injection of MER of BCG as adjuvant immunotherapy.

Fig. 62.15 Mycobacterium avium complex cellulitis in a patient on chronic CS for rheumatoid arthritis. Note the sporotrichoid (lymphocutaneous) pattern of the coalescing nodules with abscess formation.

• Disseminated infection can occur in immunocompromised hosts.

• Mycobacterium marinum infection is seen most frequently in the United States.

– Found in aquatic environments, including fish tanks and swimming pools.

– Bluish-red inflammatory nodule or pustule that may ulcerate; over time, can develop additional lesions in a sporotrichoid pattern (Fig. 62.16).

Fig. 62.16 Mycobacterium marinum infections. A range of presentations, including an erythematous plaque with scale-crust at the inoculation site on the lateral hand (A), a sporotrichoid pattern with the inoculation site on the distal third finger (B), and disseminated necrotic lesions on the face of an immunocompromised patient (C).

• DDx: other infections with sporotrichoid spread (e.g. sporotrichosis, nocardiosis) (see Table 64.7).

For further information see Ch. 75. From Dermatology, Third Edition.