Chapter 21 Movement Disorders

Diagnosis and Assessment

The term movement disorders is often used synonymously with basal ganglia or extrapyramidal diseases. However, neither of those terms adequately encompasses all the disorders included under the broad umbrella of movement disorders. Movement disorders are neurological motor disorders manifested by slowness or poverty of movement (bradykinesia or hypokinesia, such as that seen in parkinsonian disorders) at one end of the spectrum and abnormal involuntary movements (hyperkinesias) such as tremor, dystonia, athetosis, chorea, ballism, tics, myoclonus, restless legs syndrome, stereotypies, akathisias, and other dyskinesias at the other. Although motor dysfunctions resulting from upper and lower motor neuron, spinal cord, peripheral nerve, and muscle diseases usually are not classified as movement disorders, abnormalities in muscle tone (e.g., rigidity, spasticity, stiff person syndrome), incoordination (cerebellar ataxia; see Chapters 20 and 74), and complex disorders of execution of movement denoted by the term apraxia (see Chapter 10) are now included among movement disorders.

Many movement disorders have no known or established cause. The classification of these disorders, sometimes called essential or idiopathic movement disorders, are now best classifiable as primary movement disorders and distinguished from those that are secondary to identifiable diseases. In the following sections, the emphasis is on historical and clinical features that help the clinician make this distinction. Family history, including ethnic origin (e.g., Ashkenazi Jewish) and parental consanguinity, often is helpful in arriving at a diagnosis. It is crucial to recognize that the symptoms in other family members may be different from those in the patient because of variability of gene expression and penetrance and because they may have an entirely different disorder. For example, some family members of patients with primary dystonia may have dystonic features, whereas others may have predominantly tremor. Additional problems that may hamper the acquisition of an adequate family history include adoption, uncertain paternity, and even the deliberate withholding of important family information. Denial of positive family history is particularly common in patients with Huntington disease (HD) and the genetic ataxias. An adult-onset disorder may not have been evident in a family member who died at an early age. It is particularly important to exclude Wilson disease (WD) because of the specific therapy available and the universally fatal outcome of the disease if left untreated (Lorincz, 2010).

Besides documenting the movement disorder, neurological examination should search for additional findings that would help indicate the secondary nature of the problem. General physical examination must be thorough. An extremely important component of the examination is a corneal evaluation, including slit-lamp examination, to exclude the presence of a Kayser-Fleischer ring, characteristic of WD (Fig. 21.1). The nature and extent of laboratory investigations depend on clinical suspicions. Without clues from the history and physical examination, however, very few specific or special investigations assist in diagnosing these patients.

Parkinsonism

The initial feature of many basal ganglia diseases is slowness of movement (bradykinesia) and paucity or absence of movement (akinesias), often associated with rigidity and tremor (Jankovic, 2007a). Some authors have used the term hypokinesia to describe a reduction in amplitude of movement. The combination of slowness and poverty of movement and increase in muscle tone explain many parkinsonian symptoms. The term parkinsonism is used to describe a syndrome manifested by a combination of the following six cardinal features: (1) tremor at rest, (2) bradykinesia, (3) rigidity, (4) loss of postural reflexes, (5) flexed posture, and (6) freezing (motor blocks). A combination of these signs is the basis to clinically define definite, probable, and possible parkinsonism. Diagnosis of definite parkinsonism requires that at least two of these features must be present, with one of them being resting tremor or bradykinesia; probable parkinsonism consists of resting tremor or bradykinesia alone; and possible parkinsonism includes at least two of the remaining four features. The four major characteristics of parkinsonism account for most of the described clinical abnormalities: tremor, rigidity, akinesia, and postural disturbances (forming the acronym TRAP).

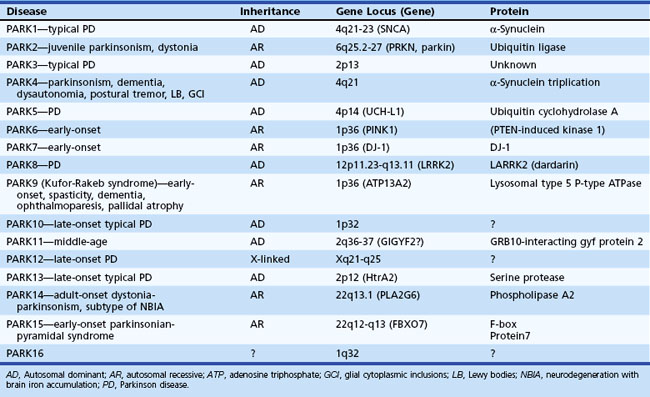

The most common cause of idiopathic parkinsonism (akinetic-rigid syndrome) is Parkinson disease (PD). As a result of advances in genetics, many forms of idiopathic parkinsonism have been found to result from mutations in specific genes, such as those coding for α-synuclein (SNCA gene), parkin (PARK2 gene), leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2 gene), or PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1 gene) protein (Table 21.1). Whereas some of the gene mutations (e.g., SNCA) are very rare causes of parkinsonism, PARK2 mutations account for up to 50% of all patients with early-onset parkinsonism, and LRRK2 mutations may account for a large proportion of cases in selected populations (e.g., North Africans, Ashkenazi Jews) (Dawson et al., 2010; Gandhi and Wood, 2010). Although less than 10% of all patients with PD have a genetic mutation, clinicians must learn about these genetic forms of parkinsonism not only to understand the pathogenic mechanisms better but also to learn how to interpret and use the increasingly available gene tests for genetic counseling (Tan and Jankovic, 2006). Because PD is idiopathic by definition, the notion of multiple Parkinson diseases is a consideration to draw attention to the different genetic causes of idiopathic parkinsonism. Besides genetic causes, there are many other causes of pure parkinsonism and of parkinsonism combined with other neurological deficits (parkinsonism-plus syndromes) (Box 21.1).

Box 21.1 Classification of Parkinsonism

II. Multisystem degenerations (“parkinsonism plus”)

III. Heredodegenerative parkinsonism

IV. Secondary (acquired, symptomatic) parkinsonism

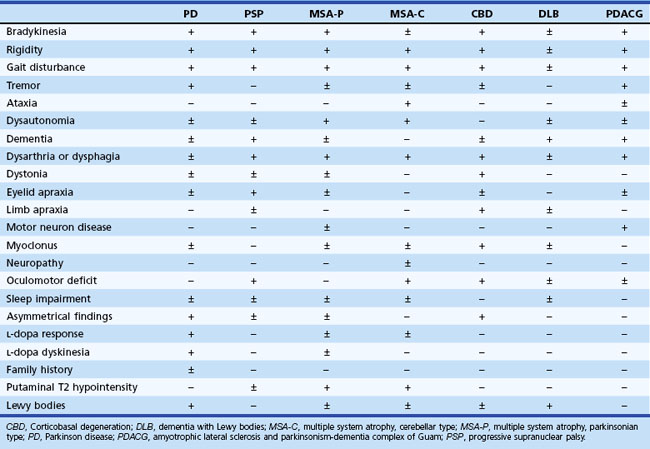

Motor Abnormalities

Early in the course of the disease, many patients with parkinsonism are unaware of any motor deficit. Often the patient’s spouse comments on a reduction in facial expression (often misinterpreted as depression), a reduction in arm swing while walking, and a slowing of activities of daily living, most notably dressing, feeding, and walking. The patient may then become aware of a reduction in manual dexterity, with slowness and clumsiness interfering with activities. PD is typically asymmetrical, especially early in the course. A painful shoulder is one of the most common early symptoms of incipient unilateral rigidity and bradykinesia. This symptom, probably related to decreased arm swing and secondary joint changes or shoulder muscle rigidity, is often misdiagnosed as bursitis, arthritis, or a rotator cuff disorder. All recreational and work tasks, household chores, and self-care functions eventually become impaired. Handwriting often becomes slower and smaller (micrographia), with speed and size decreasing as the task continues. Eventually the writing may become illegible. Use of eating utensils becomes difficult, chewing is laborious, and choking while swallowing may occur. If the latter is an early and prominent complaint, one must consider bulbar involvement in one of the parkinsonism-plus syndromes, such as progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) and multiple system atrophy (MSA) (Stefanova et al., 2009; Williams and Lees, 2009) (Table 21.2). Dressing tasks such as fastening small buttons or getting arms into sleeves are often difficult. Hygiene becomes impaired. As with most other tasks, disability is greater if the dominant arm is more affected; shaving, brushing teeth, and other repetitive movements usually are affected the most.

Speech becomes slurred and loses its volume (hypophonia), and as a result, patients often must repeat themselves. Like gait, speech may be festinating; that is, it gets faster and faster (tachyphemia). A large number of additional speech disturbances may occur, including stuttering and palilalia, involuntary repetition of a phrase with increasing rapidity. Early, pronounced voice changes often indicate a diagnosis other than PD (e.g., palilalia is more commonly a feature of PSP and MSA). A harsher, nasal quality of the voice, which is quite distinctive from the hypophonic monotone of PD, also suggests the diagnosis of PSP. A higher-pitched quivering, “whiny” voice may suggest MSA, especially if it is associated with frequent sighing, respiratory gasps, laryngeal stridor, and other respiratory problems (Mehanna and Jankovic, 2010).

Cognitive, Autonomic, and Sensory Abnormalities

The complaints of patients with parkinsonism are not limited to the motor system, and a large variety of nonmotor symptoms, many of which are probably not directly related to dopaminergic deficiency, often emerge as the disease progresses. In many cases, they become more disabling than the classic motor problems (Lim et al., 2009) (see Table 21.2). Dementia occurs in a variety of parkinsonian syndromes (see Chapters 66 and 72). Depression is also a common problem, and patients often lose their assertiveness and become withdrawn, more passive, and less motivated to socialize. The term bradyphrenia describes the slowness of thought processes and inattentiveness often seen.

Complaints related to autonomic dysfunction are also common. In all parkinsonian syndromes, constipation is a common complaint and may become severe. However, fecal incontinence does not occur in PD unless the motor disability is such that the patient cannot maneuver to the bathroom, dementia is superimposed, or impaction has led to overflow incontinence. Bladder complaints such as frequency, nocturia, and the sensation of incomplete bladder emptying may occur. Urinary incontinence is especially suggestive of MSA. A mild to moderate degree of orthostatic hypotension is common in parkinsonian disorders, and antiparkinsonian drugs often aggravate the problem (see Chapter 71). If the autonomic features, particularly erectile dysfunction, sphincter problems, and orthostatic lightheadedness, occur early or become the dominant feature, one must consider the possibility of MSA (see Chapter 66). Impotence with early loss of nocturnal or morning erections and inability to maintain erection during intercourse is suggestive of MSA. The other symptom that may precede the onset of motor problems associated with several parkinsonian disorders, particularly PD, MSA, or dementia with Lewy bodies, is rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder. One characteristic nonmotor feature of PD is excessive greasiness of the skin and seborrheic dermatitis, characteristically seen over the forehead, eyebrows, and malar area.

Visual complaints are usually not a prominent feature, with the following specific exceptions. In PD (and many other parkinsonian disorders), diplopia may occur during reading secondary to impaired convergence. Visual complaints sometimes occur in other parkinsonian disorders, particularly PSP (see Chapter 71). Oculogyric crises, which are sudden episodes of involuntary ocular deviation (most often up and to the side) in the absence of neuroleptic drug exposure, are virtually pathognomonic of parkinsonism after encephalitis lethargica, although they may occur in rare neurometabolic disorders as well. Sensory loss is not part of parkinsonism, although patients with PD may have poorly explained positive sensory complaints such as numbness and tingling, aching, and painful sensations that are sometimes quite disabling. Peripheral neuropathy suggests another disorder or an unrelated problem (e.g., diabetes mellitus), although recent evidence suggests a higher-than-expected incidence of peripheral neuropathy, possibly related to levodopa treatment and elevated methylmalonic acid levels (Toth et al., 2010).

Although a variety of neurophysiological and computer-based methods have been proposed to quantitate the severity of the various parkinsonian symptoms and signs, most studies rely on clinical rating scales, particularly the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), Hoehn and Yahr staging scale, and Schwab and England Activities of Daily Living Scale (Box 21.2). Non-demented patients can reliably self-administer and complete the historical section of the UPDRS, now available in a revised version referred to as the Movement Disorder Society (MDS)-UPDRS (www.movementdisorders.org). The revision clarifies some ambiguities and more adequately assesses the nonmotor features of PD, which are among the most disabling symptoms, particularly in more advanced stages of the disease (Goetz et al., 2008). Some clinical research studies supplement the UPDRS by a more objective timed test such as the Purdue Pegboard Test and movement and reaction times. Many scales, such as the Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire-39 (PDQ-39) and the Parkinson’s Disease Quality of Life Questionnaire (PDQL), attempt to assess the overall quality of life (Jankovic, 2008).

Box 21.2 Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) Definitions of 0–4 Scale

Mentation, Behavior, and Mood

2. Thought disorder (caused by dementia or drug intoxication)

Motor Examination

22. Rigidity (judged on passive movement of major points with patient relaxed in sitting position; cogwheeling to be ignored)

23. Finger taps (patient taps thumb with index finger in rapid succession with widest amplitude possible, each hand separately)

24. Hand movements (patient opens and closes hands in rapid succession with widest amplitude possible, each hand separately)

25. Hand pronation-supination (pronation-supination movements of hands, vertically or horizontally, with as large an amplitude as possible, both hands simultaneously)

26. Leg agility (patient taps heel on ground in rapid succession, picking up entire leg; amplitude should be about 3 inches)

27. Arising from chair (patient attempts to arise from a straight back wooden or metal chair with arms folded across chest)

30. Postural stability (response to sudden posterior displacement produced by pull on shoulders while patient erect with eyes open and feet slightly apart. Patient is prepared.)

31. Body bradykinesia (combining slowness, hesitancy, decreased arm swing, small amplitude, and poverty of movement in general)

Complications of Therapy

Dyskinesias

Clinical Fluctuations

Modified Hoehn and Yahr Staging

Stage I.5 = Unilateral disease plus axial involvement

Stage II = Bilateral disease, without impairment of balance

Stage II.5 = Mild bilateral disease, with recovery on pull test

Stage III = Mild to moderate bilateral disease; some postural instability; physically independent

Stage IV = Severe disability; still able to walk or stand unassisted

Modified Schwab and England Activities of Daily Living Scales

100%: Completely independent. Able to do all chores without slowness, difficulty, or impairment. Essentially normal. Unaware of any difficulty.

90%: Completely independent. Able to do all chores with some degree of slowness, difficulty, and impairment. Might take twice as long. Beginning to be aware of difficulty.

80%: Completely independent in most chores. Takes twice as long. Conscious difficulty and slowness.

70%: Not completely independent. More difficulty with some chores. Takes three to four times as long to perform some. Must spend a large part of the day on chores.

60%: Some dependency. Can do most chores, but exceedingly slowly and with much effort. Errors; some impossible.

50%: More dependent. Help with half of chores, slower, etc. Difficulty with everything.

40%: Very dependent. Can assist with all chores, but few periods alone.

30%: With effort, now and then does a few chores alone or begins alone. Much help needed.

20%: Nothing alone. Can be a slight help with some chores. Severe invalid periods.

10%: Totally dependent, helpless. Complete invalid.

0%: Vegetative. Functions such as swallowing, bladder, and bowel are not functioning. Bedridden.

Onset and Course

As in other movement disorders, the age at onset of a parkinsonian syndrome is clearly important in considering a differential diagnosis. Although the majority of patients are adults, parkinsonism does occur in childhood (see Box 21.1). PD usually has a slow onset and very gradual progression (Jankovic, 2005). Generally, patients with early-onset PD and those with a tremor-dominant form tend to progress at a slower rate and are less likely to have an associated cognitive decline than those with postural instability and the gait difficulty form of PD. Other disorders (e.g., those due to toxins, cerebral anoxia, infarction) may present abruptly or progress more rapidly (resulting in so-called malignant parkinsonism) or may even improve spontaneously (e.g., those due to drugs, multiple infarcts, certain forms of encephalitis).

Examination and Clinical Signs

The diagnosis of parkinsonism often is immediately apparent on first contact with the patient. The facial expression, low-volume voice, tremor, poverty of movement, shuffling gait, and stooped posture provide an immediate and irrevocable first impression of parkinsonism. However, the physician must perform a detailed assessment, searching for any atypical features in attempting to distinguish between PD and other parkinsonian disorders. Loss of facial expression (hypomimia) often is an early sign of PD. But occasional patients have a wide-eyed, anxious, worried expression due to furrowing of the brow (“procerus sign”) and deep facial folds, which strongly suggests PSP. Blink frequency usually is reduced, although blepharoclonus (repetitive spasms of the lids on gentle eye closure) and reflex blepharospasm (e.g., precipitated by shining a light into the eyes or manipulating the lids) also may be seen. Spontaneous blepharospasm and apraxia of lid opening occur less often. Patients with apraxia of lid opening (not a true apraxia) often open their eyes using their hands, and once the eyes are fixated on an object, the eyelids remain open. Primitive reflexes, including the inability to inhibit blinking in response to tapping over the glabella (Myerson sign) and palmomental reflexes, are nonspecific and are commonly present in many parkinsonian disorders (Brodsky et al., 2004).

Various types of tremor, most notably resting and postural varieties, often accompany parkinsonian disorders. Patients should be observed with hands resting on their laps or thighs, and they should be instructed to hold their arms in an outstretched position or in a horizontal position with shoulders abducted, elbows flexed, and hands palms-down in front of their faces in the so-called wing-beating position. Resting tremor often reemerges after a period of quiescence in a new position (re-emergent tremor) (Jankovic, 2008). This re-emergent tremor may be wrongly attributed to postural tremor and lead to misdiagnosis as essential tremor. A true kinetic (intention) tremor, elicited by the finger-to-nose maneuver, is much less common in patients with PD and other parkinsonian disorders and usually indicates involvement of cerebellar connections. A jerky postural tremor indicative of additional myoclonus is suggestive of a diagnosis of MSA rather than PD. Head tremor (titubation) suggests a diagnosis other than PD, such as essential tremor, dystonic neck tremor, or a cerebellar tremor associated with the cerebellar form of MSA (MSA-C), spinocerebellar atrophy, or multiple sclerosis (MS).

Rigidity is an increase in muscle tone, usually equal in flexors and extensors and present throughout the passive range of movement. This contrasts with the distribution and velocity-dependent nature of spasticity. Paratonia (or Gegenhalten), on the other hand, increases with repetitive passive movement and attempts to get the patient to relax. It may be difficult to distinguish between milder forms of paratonia and rigidity, especially in the legs. Characteristically, the performance of voluntary movements in the opposite limb (e.g., opening and closing the fist or abduction-adduction of the shoulder) brings out rigidity, a phenomenon known as activated rigidity (Froment sign). Superimposed on the rigidity may be a tremor or cogwheel phenomenon. This, like the milder forms of rigidity, is better appreciated by placing one hand over the muscles being tested (e.g., placing the left thumb over the biceps and the remaining fingers over the triceps while flexing and extending the elbow with the right hand). The distribution of the rigidity sometimes is helpful in differential diagnosis. For example, pronounced nuchal rigidity with much less hypertonicity in the limbs suggests the diagnosis of PSP, whereas an extreme degree of unilateral arm rigidity or paratonia suggests corticobasal degeneration (CBD) or corticobasal syndrome (CBS). The latter term is suggested for cases diagnosed clinically, as only 24% of such cases have pathologically proven CBD (Ling et al., 2010).

Postural disturbances are common in parkinsonian disorders. The head usually tilts forward and the body becomes stooped, often with pronounced kyphosis and varying degrees of scoliosis (Ashour and Jankovic, 2006). The arms become flexed at the elbows and wrists, with varying postural deformities in the hands, the most common being flexion at the metacarpophalangeal joints and extension at the interphalangeal joints, with adduction of all the fingers and opposition of the thumb to the index finger (striatal hand). Flexion also occurs in the joints of the legs. Variable foot deformities occur, the most common being hammer toe–like disturbances in most of the toes, occasionally with extension of the great toe (striatal foot), which may be misinterpreted as an extensor plantar response. Initially, abnormal foot posturing may be induced by action, occurring only during walking or weight bearing. The flexed or simian posture sometimes is extreme, with severe flexion at the waist (camptocormia) (Azher and Jankovic, 2005; Jankovic, 2010). Some patients, particularly those with MSA, exhibit scoliosis or tilted posture (Pisa sign). Despite the truncal flexion, the position of the hands in patients with PD often remains above the beltline because of flexion of the elbows. Occasional patients remain upright or even demonstrate a hyperextended posture. Hyperextension of the neck is particularly suggestive of PSP, whereas extreme flexion of the neck (head drop or bent spine) suggests MSA but also PD.

Postural instability is characteristic of parkinsonian disorders, particularly the postural instability and gait difficulty forms of PD, PSP, and MSA. As patients rise from a sitting position, poor postural stability, slowness, narrow base, and not repositioning the feet often combine to cause them to fall back into the chair “in a lump.” PSP patients may “rocket” out of the chair inappropriately quickly, failing to recognize their inability to maintain stability on their feet. The PD patient may require several attempts, push off the arms of the chair, or need to be pulled up by an assistant. Gait disturbances in typical parkinsonism include lack of arm swing, shortened and later shuffling stride, freezing in the course of walking (especially at a door frame or when approaching a potential obstruction or a chair), and in more severe cases, propulsion and spontaneous falls (Jankovic, 2007a). In addition, walking often brings out or exacerbates a resting tremor. To assess postural instability, the physician performs the pull test. Standing behind the patient, the examiner pulls the patient backward by the shoulders (or by a hand on the sternum), carefully remaining close behind to prevent a fall. Once postural reflexes are impaired, there may be retropulsion or multiple backward steps in response to the postural perturbation. Later there is a tendency to fall en bloc without retropulsion or even normal attempts to recover or to cushion the fall.

In PD, the base of the gait is usually narrow, and tandem gait is performed well. When the gait is wide-based, a superimposed ataxia is a consideration, as is seen in MSA-C, although some of the spinocerebellar atrophies may present with parkinsonism and ataxia (see Chapter 72). Toe walking (cock-walk) is seen in some parkinsonian disorders (e.g., due to manganese poisoning), and a peculiar loping gait may indicate the rare patient with akinesia in the absence of rigidity, which may be one phenotype of PSP. The so-called magnetic foot, or marche à petits pas, of senility (also seen in multiple infarctions, Binswanger disease, and normal pressure hydrocephalus) more commonly results in a lower-body parkinsonism, typically associated with cerebrovascular disorders such as lacunar strokes. A striking discrepancy of involvement between the lower body and the upper limbs, with normal or even excessive arm swing, is an important clue to the diagnosis of vascular parkinsonism.

Differential Diagnosis

Although dementia commonly occurs in PD, this feature, particularly when present relatively early in the course, must alert the physician to other possible diagnoses (see Chapter 66), including the coincidental association of unrelated causes of cognitive decline (Galvin et al., 2006). Prominent eye movement disturbances are found in a number of conditions, including PSP, MSA-C, postencephalitic parkinsonism, and CBD. It is important to assess not only horizontal and vertical gaze (typically impaired in PSP) but also optokinetic nystagmus to note whether vertical saccadic eye movements (particularly as the optokinetic tape moves in upward direction) are impaired, as in PSP. The oculocephalic (doll’s eye) maneuver must be performed where ocular excursions are limited, seeking supportive evidence of supranuclear gaze palsy. Patients with PSP typically have trouble making eye contact because of disturbed visual refixation. As a result of persistence of visual fixation when PSP patients turn, their head turn lags behind their body turn. Obvious pyramidal tract dysfunction usually suggests diagnoses other than PD. An exaggerated grasp response indicates disturbance of the frontal lobes and the possibility of a concomitant dementing process. Occasionally a pronounced flexed posture in the hand may be confused with a grasp reflex, and the examiner must be convinced that there is active contraction in response to stroking of the palm. The abnormalities of rapid, repetitive, and alternating movements described earlier can be confused with the clumsy awkward performance of limb-kinetic apraxia (Zadikoff and Lang, 2005). More importantly, the abnormalities in performance of repetitive movement must not be confused with the disruption of rate, rhythm, and force typical of the dysdiadochokinesia of cerebellar disease. A helpful maneuver in testing for the presence of associated cerebellar dysfunction is to have the patient tap with the index finger on a hard surface. Watching and, in particular, listening to the tapping often allows a distinction to be made between the slowness and decrementing response of parkinsonism and the irregular rate and force of cerebellar ataxia. Testing for ideomotor apraxia, as seen in CBS, should also be performed by asking the patient to mimic certain hand gestures (intransitive tasks) such as the “victory sign” or the University of Texas “hook ’em horns sign” (extension of the second and fifth finger and flexion of the third and fourth finger) or to simulate certain activities (transitive tasks [using a tool or utensil]) such as brushing teeth and combing hair. However, in the later stages of many parkinsonian disorders, rigidity and other motor disturbances may make results of these tests difficult to interpret. In PD or MSA, the less affected limb may show mirror movements as the patient attempts to perform rapid repetitive or alternating movements with the most affected limb (Espay et al., 2005). On the other hand, in CBS, the most affected limb may mirror movements performed in the less affected limb. Some patients with parkinsonism and frontal lobe involvement exhibit signs of perseveration such as the applause sign, manifested by persistence of clapping after instructing the patient to clap consecutively three times as quickly as possible. Although initially thought to be characteristic of PSP, it is also present in some patients with other parkinsonian disorders (Wu et al., 2008).

Despite a variety of sensory complaints, patients with PD do not show prominent abnormalities on the sensory examination, aside from the normal increase in vibration threshold that occurs with age. Cortical sensory disturbances suggest a diagnosis of CBS. Wasting and muscle weakness are not characteristic of PD, although later in the course of the disease, severely disabled patients show disuse atrophy and severe problems in initiating and maintaining muscle activation that are often difficult to separate from true weakness. Combinations of upper and lower motor neuron weakness occur in several other parkinsonian disorders (see Table 21.2).

Tremor

Tremor is rhythmic oscillation of a body part, produced by either alternating or synchronous contractions of reciprocally innervated antagonistic muscles. Tremors usually have a fixed frequency, although the rate may appear irregular. The amplitude of the tremor can vary widely, depending on both physiological and psychological factors. The basis of further categorization is the position, posture, and motor performance necessary to elicit it. A rest tremor occurs with the body part in complete repose, although when a patient totally relaxes or sleeps, this tremor usually disappears. Maintenance of a posture, such as extending the arms parallel to the floor, reveals a postural tremor; moving the body part to and from a target brings out an intention tremor. The use of other descriptive categories has caused some confusion in tremor terminology. Action tremor has been used for both postural and kinetic (also known as intention) tremors. Whereas a kinetic tremor is present throughout goal-directed movement, the term terminal tremor applies to the component of kinetic tremor that exaggerates when approaching the target. Ataxic tremor refers to a combination of kinetic tremor plus limb ataxia. Box 21.3 provides a list of differential diagnoses for the three major categories of tremor and other rhythmic movements that occasionally are confused with tremor.

Box 21.3 Classification and Differential Diagnosis of Tremor

Postural Tremors

Exaggerated physiological tremor; these factors can also aggravate other forms of tremor:

Essential tremor (familial or sporadic)

Primary writing tremor and other task-specific tremors

Diseases of cerebellar outflow (dentate nuclei, interpositus nuclei, or both, and superior cerebellar peduncle):

Miscellaneous rhythmic movement disorders

Rhythmic movements in dystonia (dystonic tremor, myorrhythmia)

Rhythmic myoclonus (segmental myoclonus, e.g., palatal or branchial myoclonus, spinal myoclonus), myorrhythmia

CNS, Central nervous system; MS, Multiple sclerosis; PD, Parkinson disease; WD, Wilson disease.

Common Symptoms

A description of symptoms occurs under the various categories of tremor. All people have a normal or physiological tremor demonstrable with sensitive recording devices. Two common pathological tremor disorders that are often confused are parkinsonian rest tremor and essential tremor. Although Chapter 71 discusses both conditions in detail, we discuss helpful distinguishing points here in view of the frequency of misdiagnosis.

Postural Tremor

In contrast to a pure rest tremor, postural tremors, especially with pronounced terminal accentuation, can result in significant disability. Many such patients are mistaken as having “bad nerves.” People who perform delicate work with their hands (e.g., jewelers, surgeons) become aware of this form of tremor earlier than most. The average person usually first appreciates tremor in the acts of feeding and writing. Carrying a cup of liquid, pouring, or eating with a spoon often brings out the tremor. Writing is tremulous and sloppy, questioning the patient’s signature on a check. The voice may be involved in essential tremor. Again, anxiety and stress worsen the tremor, and patients often notice that their symptoms are especially bad in public. The most common cause of postural tremor seen in movement disorders clinics is essential tremor (Jankovic, 2009).

Other Clues in the History

Although patients with several different types of tremor may indicate that alcohol transiently reduces their shaking, a striking response to small amounts of alcohol is particularly characteristic of essential tremor (Mostile and Jankovic, 2010). Clues to the possible presence of factors aggravating the normal physiological tremor (see Box 21.3) require further inquiry.

Examination

In addition to clinical examination, various physiological, accelerometric, and other computer-based techniques can be employed to assess tremor, but a clinical rating scale usually is most practical, particularly in clinical trials. The Tremor Research Group (TRG) has developed a rating scale that can be used to quantitatively assess all types of tremor, particularly essential tremor, the most common type encountered in clinical practice (Box 21.4). The TRG Essential Tremor Rating Scale (TETRAS) is currently being validated and has been found to correlate well with quantitative computer-based systems (Mostile et al., 2010). Besides rest tremor, postural tremor, and kinetic limb tremor, examine patients for tremor of the head. With the patient seated or standing, head tremor may be evident as vertical (“yes-yes”) nodding (tremblement affirmatif) or side-to-side (“no-no”) horizontal shaking (tremblement negatif). There may be combinations of the two, with rotatory movements. Subtle head tremors may only be appreciated when the examiner holds the patient’s cranium while testing with the other hand for extreme lateral eye movements. Head tremors usually range from 1.5 to 5 Hz and are most commonly associated with essential tremor or cervical dystonia and with diseases of the cerebellum and its outflow pathways. A parkinsonian rest tremor may involve the jaw and lips. A similar tremor of the perioral and nasal muscles, the rabbit syndrome, has been associated with antipsychotic drug therapy but also occurs in PD. In many disorders, voluntary contraction of the facial muscles induces an action tremor. In addition, a postural tremor of the tongue often is present on tongue protrusion. In the case of tremors of head and neck structures, it is important to observe the palate at rest for the slower rhythmic movements of palatal myoclonus (also called palatal tremor). Occasionally, tremor spares the palate, with similar movements affecting other branchial structures. Demonstration of a voice tremor requires asking the patient to hold a note as long as possible. Superimposed on the vocal tremulousness may be a harsh, strained quality or abrupt cessation of airflow during the course of maintaining the note, which suggests a superimposed dystonia of the larynx (spasmodic dysphonia).

Box 21.4 Tremor Research Group Rating Scale

Instructions for Completing The Observed Tremor Portion

1. Head tremor: Subject is seated upright. The head is observed for 10 seconds in midposition and for 5 seconds each during several provocative maneuvers. First the subject is asked to rotate his or her head to the maximum lateral positions slowly in each direction. The subject is then asked to deviate his or her eyes to the maximum lateral positions while the examiner gently touches the subject’s chin.

2a. Face tremor: Subject is seated upright and asked to smile and pucker his or her lips, each for 5 seconds. Tremor is specifically assessed for the lower facial muscles (excluding jaw and tongue) and upper face (eye closure).

2b. Tongue tremor: Subject is seated upright and asked to open his or her mouth for 5 seconds and then stick out his or her tongue for 5 seconds.

2c. Jaw tremor: Subject is seated upright and asked to maximally open his or her mouth and clench the jaw for 5 seconds.

3. Voice tremor: First assess speech during normal conversation; then ask subject to produce an extended “aaa” sound and “eee” sound for 5 seconds each.

4. Arm tremor: Subject is seated upright. Tremor is assessed during four arm maneuvers (rest, forward horizontal reach posture, lateral “wing-beating” posture, and kinesis) for 5 seconds in each posture. Left and right arms may be assessed simultaneously. Amplitude assessment should be estimated using the maximally displaced point of the hand at the point of greatest displacement along any single plane. For example, the amplitude of a pure supination-pronation tremor, pivoting around the wrist, would be assessed at either the thumb or fifth digit.

5. Trunk tremor: Subject is comfortably seated in a chair and asked to flex both legs at the hips 30 degrees above parallel to the ground for 5 seconds. The knees are passively bent so that the lower leg is perpendicular to the ground. The legs are not allowed to touch. Tremor is evaluated around the hip joints and the abdominal muscles.

6. Leg tremor action: Subject is comfortably seated and asked to raise his or her legs parallel to the ground with knees extended for 5 seconds. The legs are slightly abducted so they do not touch. Tremor amplitude is assessed at the end of the feet.

7. Leg tremor rest: Subject is comfortably seated with knees flexed and feet resting on the ground. Tremor amplitude is assessed at the point of maximal displacement.

8. Standing tremor: Subject is standing, unaided if possible. The internal malleoli are 5 cm apart. Arms are down at the sides. Tremor is assessed at any point on the legs or trunk.

9. Spiral drawings: Ask the subject to draw the requested figures. Test each hand without leaving the hand or arm on the table. Use only a ballpoint pen.

10. Handwriting: Have patient write “Today is a nice day.”

11. Hold pencil approximately 1 mm above a point on a piece of paper for 10 seconds.

12. Pour water from one glass into another, using styrofoam coffee cups filled 1 cm from top. Rated separately for right and left hands.

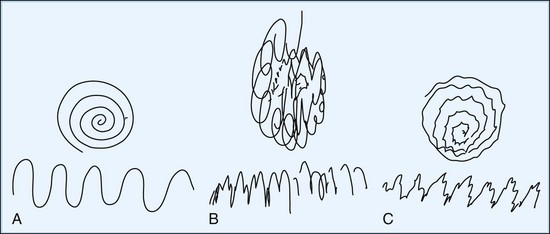

Having the patient point the index fingers at each other under the nose (without touching the fingers together or touching the face) with the arms abducted at the sides and the elbows flexed can demonstrate both distal tremor in the hands and proximal tremors. An example of proximal tremor is the slower wing-beating tremor of cerebellar outflow pathway disease, as may be seen in WD. Tremor during the course of slowly pronating and supinating the forearms with the arms outstretched or with forceful abduction of the fingers occurs in patients with primary writing tremor. Holding a full cup of water with the arm outstretched often amplifies a postural tremor, and picking up the full cup, bringing it to the mouth, and tipping it to drink enhances the terminal tremor, often causing spillage. In addition to writing, one should have the patient draw with both hands separately. Useful drawing tasks include an Archimedes spiral, a wavy line from one side of the page to the other (Fig. 21.2), and an attempt to carefully draw a line or spiral between two well-defined, closely opposed borders. Another useful test designed to bring out position-specific tremor is the dot approximation test, in which the patient is instructed to be seated at the desk with elbow elevated and to hold the tip of the pen or pencil (for at least 10 seconds) as close as possible to a dot drawn on a sheet of paper without touching it. Many patients with action tremors note marked exacerbation of their tremor during this specific task.

Certain tremors persist in all positions. Disease in the midbrain involving the superior cerebellar peduncle near the red nucleus (possibly also involving the nigrostriatal fibers) results in the so-called midbrain, or rubral, tremor (Holmes tremor). Characteristically, this form of tremor combines features of the three tremor classes. It is often present at rest, increases with postural maintenance, and increases still further, sometimes to extreme degrees, with goal-directed movement. Tremor also may be a feature of psychiatric disease, representing a conversion reaction or even malingering. Usually, certain features are atypical or incongruous. This psychogenic tremor differs from most organic tremors in that the frequency is often quite variable, and concentration and distraction often abate the tremor instead of increasing it (Kenney et al., 2007; Thomas and Jankovic, 2010).

Dystonia

Dystonia is a disorder dominated by sustained muscle contractions, which often cause twisting and repetitive movements or abnormal postures (Jankovic, 2007b). The term dystonia is used in three major contexts: (1) to describe the specific form of involuntary movement (i.e., a physical sign), (2) to refer to a syndrome caused by a large number of different disease states, or (3) to refer to the idiopathic form of dystonia, in which these movements usually occur in isolation without additional neurological abnormalities (Box 21.5).

Box 21.5 Etiological Classification of Dystonia

II. Secondary dystonia (dystonia-plus syndromes)

III. Heredodegenerative diseases (typically not pure dystonia)

Another common error in diagnosis is the mislabeling of dystonia as hysteria. Stress and anxiety aggravate the movements, and rest and even hypnosis alleviate the movements. Patients often discover a variety of peculiar maneuvers (sensory tricks) that they can use to lessen or even completely abate the dystonic movements and postures (discussed in this chapter and in Chapter 71). The abnormal movements and postures may occur only during the performance of certain acts and not others that use the same muscles. An example of this action, task-specific dystonia, is involvement of the hand only in writing (writer’s cramp or graphospasm) or playing a musical instrument, but not with other manual tasks such as using utensils. Dystonia of the oromandibular region only on speaking or eating is another example of task-specific dystonia, as is dystonia in legs and trunk that occurs only on walking forward but not on walking backward, climbing stairs, or running. On the other hand, some dystonias occur only during running (Wu and Jankovic, 2006). A final source of possible confusion with hysteria is the occurrence of dystonia after injury to the affected limb or after prolonged immobilization such as casting. Such peripherally induced dystonia, which is usually fixed rather than mobile, may be associated with a complex regional pain syndrome (previously referred to as reflex sympathetic dystrophy), depression, and personality changes and may occur on a background of secondary gain or litigation and other features of psychogenic dystonia (Gupta and Lang, 2009; Thomas and Jankovic, 2010).

Common Symptoms

Dystonia can affect almost all striated muscle groups. Common symptoms include forced eyelid closure (blepharospasm); jaw clenching, forced jaw opening, or involuntary tongue protrusion (oromandibular or lingual dystonia); a harsh, strained, or breathy voice (laryngeal dystonia or spasmodic dysphonia); and involuntary deviation of the neck in any plane or combination of planes (cervical dystonia or spasmodic torticollis). Other symptoms are spasms of the trunk in any direction, which variably interfere with lying, sitting, standing, or walking (axial dystonia); interference with manual tasks (often only specific tasks in isolation: the occupational cramps); and involvement of the leg, usually with inversion and plantar flexion of the foot, causing the patient to walk on the toes. All these disorders may slowly progress to the point of complete loss of voluntary function of the affected part. On the other hand, only certain actions may be impaired, and the disorder may remain focal in distribution. Chapter 71 deals with each of these forms of dystonia in more detail.

The age at onset and distribution of dystonia often are helpful in determining the possible cause. Box 21.5 details the many causes of secondary dystonia. Whereas some patients with dystonia have “pure dystonia” without any other neurological deficit (primary dystonia), others have additional clinical features (dystonia-plus syndrome) such as parkinsonism, spasticity, weakness, myoclonus, dementia, seizures, and ataxia. Typically, childhood-onset primary dystonia (e.g., classic, Oppenheim, or DYT1 dystonia) begins in distal parts of the body (e.g., graphospasm, foot inversion) and spreads to a generalized dystonia. On the other hand, dystonia beginning in adult life usually is limited to one or a small number of contiguous regions such as the face and neck, remains focal or segmental, and rarely becomes generalized. Generalized involvement or onset in the legs in an adult usually implies the possibility of a secondary cause such as PD or some other parkinsonian disorder. Involvement of one side of the body (hemidystonia) is strong evidence of a lesion in the contralateral basal ganglia, particularly the putamen (Wijemanne and Jankovic, 2009). Most primary dystonias start as action dystonia occurring during some activity such as writing and walking or running, but consider peripheral or central trauma and psychogenic dystonia when the dystonia occurs at rest and consists of a fixed posture. A fixed posture maintained during sleep or anesthesia implies superimposed contractures or a musculoskeletal disturbance mimicking the postures of dystonia. Although rest and sleep lessens dystonia in many, some note a striking diurnal variation. The diurnal variation manifests with little or no dystonia on rising in the morning, followed by the progressive development of problems as the day goes on, sometimes to the point of becoming unable to walk late in the day. This diurnal variability strongly suggests a diagnosis of dopa-responsive dystonia. Important clues to dystonia causation are (1) the nature of symptom onset (sudden versus slow) and (2) its course, whether rapid or slow progression or episodes of spontaneous remission.

The family history must be reviewed in detail with the awareness that affected relatives may have limited or distinctly different involvement from that of the patient. The categorization of genetic dystonias according to loci is somewhat arbitrary, from DYT1 to DYT20 (Houlden et al., 2010; Müller, 2009). Obtaining a birth and developmental history is critical in view of the frequency of dystonia after birth trauma, birth anoxia, and kernicterus. As with the other dyskinesias, seek a history of such features as previous encephalitis, drug use, and head trauma. There is also increasing support for the ability of peripheral trauma to precipitate various forms of dystonia, and occasionally this is combined with a complex regional pain syndrome, also called reflex sympathetic dystrophy.

Examination

Action dystonia is commonly the earliest manifestation of primary (idiopathic) dystonia. It is important to observe patients performing the acts that are most affected. Later, other tasks precipitate similar problems, the use of other parts of the body causes the dystonia to become evident in the originally affected site, and the dystonia may overflow to other sites. Still later, dystonia is periodically evident at rest, and even later the posturing may be persistent and difficult to correct passively, especially when secondary joint contractures develop. A significant deviation from this progression, particularly with the early appearance of dystonia at rest, should encourage the physician to search carefully for a secondary cause (see Box 21.5).

Depending on the cause of the dystonia, several other neurological abnormalities may be associated. Consider WD in any patient with onset of dystonia before age 60 (Mak and Lam, 2008). Many secondary dystonic disorders (listed in Box 21.5 and discussed in Chapter 71) result in additional psychiatric or cognitive disturbances, seizures, or pyramidal tract or cerebellar dysfunction. Ocular motor abnormalities suggest a diagnosis of Leigh disease, dystonic lipidosis, ataxia-telangiectasia, ataxia-oculomotor apraxia syndrome, HD, Machado-Joseph disease, or other spinocerebellar atrophies. Optic nerve or retinal disease raises the possibility of Leigh disease, other mitochondrial cytopathies, GM2 gangliosidosis, ceroid lipofuscinosis, and neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA) (McNeill et al., 2008). One of the most common causes of NBIA is pantothenate kinase–associated neurodegeneration, previously called Hallervorden-Spatz disease (Schneider et al., 2009). Other causes include neuroferritinopathy, infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy, aceruloplasminemia, and PLA2G6-associated neurodegeneration. Lower motor neuron and peripheral nerve dysfunction occur with neuroacanthocytosis, ataxia-telangiectasia, ataxia-oculomotor apraxia syndrome, metachromatic leukodystrophy, Machado-Joseph disease, and other multisystem degenerations. Occasionally, prominent dystonic postures occur secondary to profound proprioceptive loss due to peripheral nerve, spinal cord, or brain lesions. The dystonia itself may cause additional neurological problems such as spinal cord or cervical root compression from long-standing torticollis, and peripheral nerve entrapment from limb dystonia. Also, independent of the cause, long-standing dystonic muscle spasms often result in hypertrophy of affected muscles (e.g., the sternocleidomastoid muscle in cervical dystonia).

Although the general medical examination must be thorough, it is usually unrevealing. As always, carefully seek the ophthalmological and systemic signs of WD. Abdominal organomegaly also may indicate a storage disease. Severe self-mutilation is typical of Lesch-Nyhan disease. Minor tongue and lip mutilation is seen in neuroacanthocytosis, in which orolingual action dystonia may be prominent (Walker et al., 2006). Oculocutaneous telangiectasia and evidence of recurrent sinopulmonary infections suggest ataxia-telangiectasia. Musculoskeletal abnormalities may simulate dystonia; rarely, dysmorphic features may serve as a clue to a mucopolysaccharidosis.

Chorea

The term chorea derives from the Greek choreia, meaning “a dance.” This hyperkinetic movement disorder consists of irregular, unpredictable, brief, jerky movements that flow randomly from one part of the body to another (Jankovic, 2009). The term choreoathetosis describes slow chorea, typically seen in patients with cerebral palsy. Besides these disorders, there are numerous other causes of chorea (Cardoso et al., 2006), most of which are listed in Box 21.6.

Box 21.6 Etiological Classification of Chorea

Developmental and aging choreas

Drugs: neuroleptics (tardive dyskinesia), antiparkinsonian drugs, amphetamines, cocaine, tricyclic antidepressants, oral contraceptives

Toxins: alcohol intoxication and withdrawal, anoxia, carbon monoxide, manganese, mercury, thallium, toluene

Other Clues in the History

Age at onset and manner of progression vary depending on the cause. A helpful distinction made here is between benign hereditary chorea, associated with TITF1 gene (14q13.1-q21.1) mutation, and HD (Kleiner-Fisman and Lang, 2007). In the former, chorea typically begins in childhood with a slow progression and little cognitive change, whereas HD presenting in childhood is more often of the akinetic-rigid variety, with severe mental changes and rapid progression.

In most cases, the onset of chorea is slow and insidious. An abrupt or subacute onset is more typical of many of the symptomatic causes of chorea, such as Sydenham chorea, hyperthyroidism, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), cerebral infarcts, and neuroleptic drug withdrawal (withdrawal emergent syndrome) (Mejia and Jankovic, 2010). A pattern of remissions and exacerbations suggests the possibility of drugs, SLE, and rheumatic fever, whereas brief (minutes to hours) bouts of involuntary movement indicate a paroxysmal dyskinesia.

A recent history of streptococcal throat infection and musculoskeletal or cardiovascular problems in a child suggests a diagnosis of rheumatic (Sydenham) chorea (Cardoso et al., 2006). Rheumatic chorea tends to occur every 5 to 10 years in a community when a new population of children becomes susceptible to Streptococcus infection. One may obtain a previous history of rheumatic fever, particularly in women who develop chorea during pregnancy or while taking birth control pills. Chorea gravidarum may be more common in women with prior history of rheumatic chorea. The individual contractions in Sydenham disease are slightly longer (>100 msec) compared to those in HD (50 to 100 msec), and there are often associated features such as dysarthria, oculogyric deviations, “milkmaid’s grip,” obsessive-compulsive behavior and other features, including the prior history of streptococcal infection, that support the diagnosis of Sydenham disease.

A careful family history is crucial. The most common cause of inherited chorea is HD, which has fully penetrant autosomal dominant transmission (Frank and Jankovic, 2010). The family history can be misleading, however, because the clinical features of the disease in other family members may have been mainly behavioral, and psychiatric disturbances and the chorea hardly noticed.

Examination

Respiratory irregularities are common, especially in tardive dyskinesia, but are also present in other movement disorders (Mehanna and Jankovic, 2010). Periodic grunting, respiratory gulps, humming, and sniffing may be present in this and other choreic disorders, including HD. Other movement disorders often combine with chorea. Dystonic features probably are the most common and are seen in many conditions. Less common but well recognized are parkinsonism (e.g., with juvenile HD, neuroacanthocytosis, and WD), tics (e.g., in neuroacanthocytosis), myoclonus (e.g., in juvenile HD), tremor (e.g., in WD and HD), and ataxia (e.g., in juvenile HD and some spinocerebellar ataxias). Tone usually is normal to low. Muscle bulk is typically preserved, although weight loss and generalized wasting are common in HD. When distal weakness and amyotrophy are present, one must consider accompanying anterior horn cell or peripheral nerve disease, as in neuroacanthocytosis, ataxia-telangiectasia, Machado-Joseph disease, and spinocerebellar ataxias (see Chapter 72). Reduced tendon reflexes occur. On the other hand, chorea often results in hung-up and pendular reflexes, probably caused by the occurrence of a choreic jerk after the usual reflex muscle contraction.

Depending on the cause (see Box 21.6), several other neurological disturbances may be associated with chorea. In HD, for example, cognitive changes, motor impersistence (e.g., difficulty maintaining eyelid closure, tongue protrusion, constant handgrip), apraxias (especially orolingual), and oculomotor dysfunction are all quite common (see Chapter 71). Milkmaid’s grip, appreciated as an alternating squeeze and release when the patient is asked to maintain a constant, firm grip of the examiner’s fingers, probably is caused by a combination of chorea and motor impersistence.

Tardive Dyskinesia

Distinguish the usual movements seen in tardive dyskinesia from those of chorea. In contrast to the random and unpredictable flowing nature of chorea, tardive dyskinesia usually demonstrates repetitive stereotypical movements, which are most pronounced in the orolingual region (Mejia and Jankovic, 2010). These include chewing and smacking of the mouth and lips, rolling of the tongue in the mouth or pushing against the inside of the cheek (bon-bon sign), and periodic protrusion or flycatcher movements of the tongue. The speed and amplitude of these movements can increase markedly when the patient is concentrating on performing rapid alternating movements in the hands. Patients often have a striking degree of voluntary control over the movements and may be able to suppress them for a prolonged period when asked to do so. On distraction, however, the movements return immediately. Despite severe facial movements, voluntary protrusion of the tongue is rarely limited, and this act often dampens or completely inhibits the ongoing facial movements. This contrasts with the pronounced impersistence of tongue protrusion seen in HD, which is far out of proportion to the degree of choreic involvement of the tongue. Besides stereotypies, many other movement disorders are associated with the use of dopamine receptor blockers (Table 21.3).

| Acute, Transient | Chronic, Persistent |

|---|---|

| Dystonic reaction | Tardive stereotypy |

| Parkinsonism | Tardive chorea |

| Akathisia | Tardive dystonia |

| Neuroleptic malignant syndrome | Tardive akathisia |

| Tardive tics | |

| Tardive myoclonus | |

| Tardive tremor | |

| Persistent parkinsonism | |

| Tardive sensory syndrome |

Modified from Jankovic, J., 1995. Tardive syndromes and other drug-induced movement disorders. Clin Neuropharmacol 18, 197-214.

Tardive dyskinesia caused by neuroleptic drugs such as the antipsychotics and other dopamine receptor blockers, particularly metoclopramide, is not the only cause of stereotypical oro-bucco-linguo-masticatory movements (Mejia and Jankovic, 2010). Other drugs, particularly dopamine agonists in PD, anticholinergics, and antihistamines, cause a similar form of dyskinesia. Multiple infarctions in the basal ganglia and possibly lesions in the cerebellar vermis result in similar movements. Older adults, especially the edentulous, often have a milder form of orofacial movement, usually with minimal lingual involvement. Here, as in tardive dyskinesia, inserting dentures in the mouth may dampen the movements, and placing a finger to the lips can also suppress them. Another important diagnostic consideration and source of clinical confusion is idiopathic oromandibular dystonia. Orofacial and limb stereotypies, often preceded by psychiatric symptoms, may be also seen in women with ovarian teratomas, and less frequently in males with testicular tumors, as part of anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) encephalitis (Florance et al., 2009).

Ballism

Box 21.7 lists the various causes of hemiballism. These flinging movements often are extremely disabling to patients, who drop things from their hands or damage closely placed objects. Self-injury is common, and examination often reveals multiple bruises and abrasions. Additional signs and symptoms depend on the cause, location, and extent of the lesion, which is usually in the contralateral subthalamic nucleus or striatum (see Chapter 71).

Box 21.7 Causes of Ballism

Infarction or ischemia, including transient ischemic attacks; usually lacunar disease, hypertension, diabetes, atherosclerosis, vasculitis, polycythemia, thrombocytosis, other causes

Other focal lesions (e.g., abscess, arteriovenous malformation, tuberculoma, toxoplasmosis, multiple sclerosis plaque, encephalitis, subdural hematoma)

Tics

Tics are the most varied of all movement disorders. Patients with Tourette syndrome, the most common cause of tics, manifest motor, vocal, or phonic tics and a wide variety of associated symptoms (Jankovic, 2009). Tics are brief and intermittent movements (motor tics) or sounds (phonic tics). Motor tics typically consist of sudden, abrupt, transitory, often repetitive, and coordinated (stereotypical) movements that may resemble gestures and mimic fragments of normal behavior, vary in intensity, and repeated at irregular intervals. The movements are most often brief and jerky (clonic); however, slower, more prolonged movements (tonic or dystonic tics) also occur. Several other characteristic features are helpful in distinguishing this movement disorder from other dyskinesias. Patients usually experience an inner urge to make the movement or a local premonitory sensation, temporarily relieved by its performance. Tics are voluntarily suppressible for variable periods, but this occurs at the expense of mounting inner tension and the need to allow the tic to occur. Indeed, a large proportion people with tics, when questioned carefully, admit that they intentionally produce the movements or sounds that comprise their tics (in contrast to most other dyskinesias) in response to the uncontrollable inner urge or a premonitory sensation. Box 21.8 provides examples of the various types of tics. Motor and phonic tics are divisible further as simple or complex. Simple motor tics are random, brief, irregular muscle twitches of isolated body segments, particularly the eyelids and other facial muscles, the neck, and the shoulders. In contrast, complex motor tics are coordinated, patterned movements involving a number of muscles in their normal synergistic relationships. A wide variety of other behavioral disturbances may be associated with tic disorders, and it is sometimes difficult to separate complex tics from some of these comorbid disorders. These comorbid disturbances include obsessive-compulsive behavior, copropraxia (obscene gestures), echopraxia (mimicked gestures), hyperactivity with attentional deficits and impulsive behavior, and externally directed and self-destructive behavior, including self-mutilation. Some Tourette syndrome patients also manifest sudden and transitory cessation of all motor activity (blocking tics), including speech, without alteration of consciousness. These blocking tics are caused by either prolonged tonic or dystonic tics that interrupt ongoing motor activity such as speech (intrusions), or by a sudden inhibition of ongoing motor activity (negative tic).

Box 21.8 Phenomenological Classification of Tics

Simple Motor Tics

Eye blinking; eyebrow raising; nose flaring; grimacing; mouth opening; tongue protrusion; platysma contractions; head jerking; shoulder shrugging, abduction, or rotation; neck stretching; arm jerks; fist clenching; abdominal tensing; pelvic thrusting; buttock or sphincter tightening; hip flexion or abduction; kicking; knee and foot extension; toe curling

Simple and complex phonic tics comprise a wide variety of sounds, noises, or formed words (see Box 21.8). The term vocal tic usually applies to these noises. However, because many of these sounds do not use the vocal cords, we prefer the term phonic tic. Although the presence of phonic tics is required for the diagnosis of definite Tourette syndrome, this criteria is artificial because phonic tics are essentially motor tics that result in abnormal sounds. Possibly the best-known (although not the most common) example of complex phonic tic is coprolalia, the utterance of obscenities or profanities. These are often slurred or shortened or may intrude into the patient’s thoughts but not become verbalized (mental coprolalia) (Freeman et al., 2009).

Common Symptoms

Box 21.9 lists causes of tic disorders. Most are primary or idiopathic, and within this group, the onset almost always occurs in childhood or adolescence (Tourette syndrome). The male-to-female ratio is approximately 3 : 1. Idiopathic tics occur on a spectrum from a mild, transitory, single, simple motor tic to chronic, multiple, simple, and complex motor and phonic tics.

Box 21.9

Etiological Classification of Tics

Modified from Jankovic, J., 2001. Tourette’s syndrome. N Engl J Med 345, 1184–1192.

Patients and their families complain of a wide variety of symptoms (see Box 21.8). They may have seen numerous other specialists (e.g., allergists for repetitive sniffing, otolaryngologists for throat clearing, ophthalmologists for excessive eye blinking or eye rolling, and psychologists and psychiatrists for various neurobehavioral abnormalities). Often, someone close to the patient or a teacher suggests the diagnosis of Tourette syndrome to the family after learning about it in the media. Children may verbalize few complaints or feel reluctant to speak of the problem, especially if they have been subject to ridicule by others. Even young children, when questioned carefully, can provide the history of urge to perform the movement that gradually culminates in the release of a tic and the ability to control the tic voluntarily at the expense of mounting inner tension. Children may be able to control the tics for prolonged periods but often complain of difficulty concentrating on other tasks while doing so. Some give a history of requesting to leave the schoolroom and then releasing the tics in private (e.g., in the washroom). Peers and siblings often chastise or ridicule the patient, and parents or teachers, not recognizing the nature of the disorder, may scold or punish the child for what are thought to be voluntary bad habits (indeed, an older term for tics is habit spasms).

Examination

In most patients with tics, the neurological examination is entirely normal. In patients with primary tic disorders, the presence of other neurological, cognitive, behavioral, and neuropsychological disturbances may simply relate to extension of the underlying cerebral dysfunction beyond the core that accounts for pure tic phenomena. Patients with secondary forms of tics (e.g., neuroacanthocytosis, tardive tics) may demonstrate other involuntary movements such as chorea, dystonia, and other neurological deficits (see Box 21.8). Careful interview stressing the subjective features that precede or accompany tics usually allows the distinction between true dystonia or myoclonus, and dystonic or clonic tics.

Myoclonus

Myoclonus is a sudden, brief, shocklike involuntary movement possibly caused by active muscle contraction (positive myoclonus) or inhibition of ongoing muscle activity (negative myoclonus). The differential diagnosis of myoclonus is broader than that of any other movement disorder (Table 21.4). To exclude muscle twitches, such as fasciculations caused by lower motor neuron lesions, some authors have insisted that an origin in the CNS be a component of the definition. Although the majority of cases of myoclonus originate in the CNS, occasional cases of brief shocklike movements clinically indistinguishable from CNS myoclonus occur with spinal cord or peripheral nerve or root disorders.

| PHYSIOLOGICAL MYOCLONUS (NORMAL SUBJECTS) |

The clinical patterns of myoclonus vary widely. The frequency varies from single, rare jerks to constant, repetitive contractions. The amplitude may range from a small contraction that cannot move a joint to a very large jerk that moves the entire body. The distribution ranges from focal involvement of one body part, to segmental (involving two or more contiguous regions), to multifocal, to generalized. When the jerks occur bilaterally, they may be symmetrical or asymmetrical. When they occur in more than one region, they may be synchronous in two body parts (within milliseconds) or asynchronous. Myoclonus usually is arrhythmic and irregular, but in some patients it is very regular (rhythmic), and in others there may be jerky oscillations that last for a few seconds and then fade away (oscillatory). Myoclonic jerks may occur spontaneously without a clear precipitant or in response to a wide variety of stimuli, including sudden noise, light, visual threat, pinprick, touch, and muscle stretch. Attempted movement (or even the intention to move) may initiate the muscle jerks (action or intention myoclonus). Palatal myoclonus is a form of segmental myoclonus manifested by rhythmic contractions of the soft palate. The rhythmicity has encouraged the alternative designation of palatal tremor. Symptomatic palatal myoclonus/tremor, usually manifested by contractions of the levator palatini, may persist during sleep; this form of palatal myoclonus usually is associated with some brainstem disorder. In contrast, essential palatal myoclonus/tremor consists of rhythmic contractions of the tensor palatini, often associated with a clicking sound in the ear, and disappears with sleep. Symptomatic but not essential palatal myoclonus often is associated with hypertrophy of the inferior olive. Another term proposed for essential palatal tremor is isolated palatal tremor, with several different subtypes or causes possible, including tics, psychogenic, and volitional (Zadikoff et al., 2006).

Common Symptoms

As may be seen from the foregoing description and the long list of possible causes of myoclonus, the symptoms in these patients are quite varied. For simplification, we briefly review the possible symptoms with respect to four major etiological subcategories in Table 21.4.

In the essential myoclonus group, patients usually complain of isolated muscle jerking in the absence of other neurological deficits (with the possible exception of tremor and dystonia). The movements may begin at any time from early childhood to late adult life and may remain static or progress slowly over many years. The family history may be positive, and some patients note a striking beneficial effect of alcohol (Mostile and Jankovic, 2010). Associated dystonia, present in some patients, also may respond to ethanol. Essential myoclonus and myoclonus dystonia are probably the same disorder.

In the disorders classified as causing symptomatic myoclonus, seizures may occur, but the encephalopathy (either static or progressive) is the feature that predominates. Many different myoclonic patterns occur in this broad category. As can be appreciated from a review of Table 21.4, a plethora of other neurological and systemic symptoms may accompany the encephalopathy. Two clinical subcategories of this larger grouping are distinguishable to assist in differential diagnosis. In progressive myoclonic epilepsy, myoclonus, seizures, and encephalopathy predominate, whereas in progressive myoclonic ataxia (often called Ramsay Hunt syndrome), myoclonus and ataxia dominate the clinical picture, with less frequent or severe seizures and mental changes. Myoclonus may also originate in the brainstem and spinal cord. Spinal segmental myoclonus often is rhythmic and limited to muscles innervated by one or a few contiguous spinal segments. Propriospinal myoclonus is another type of spinal myoclonus that usually results in flexion jerks of the trunk.

Examination

The distribution of the myoclonus is helpful in classifying the myoclonus and considering possible etiologies. Focal myoclonus may be more common in disturbances of an isolated region of the cerebral cortex. Segmental involvement, particularly when rhythmic, may occur with brainstem lesions (e.g., branchial or palatal myoclonus) or spinal lesions (spinal myoclonus) (Esposito et al., 2009). Multifocal or generalized myoclonus suggests a more diffuse disorder, particularly involving the reticular substance of the brainstem. When multiple regions of the body are involved, it is helpful to attempt to estimate whether movements are occurring in synchrony. It is sometimes difficult to do this clinically, and multichannel electromyographic (EMG) monitoring needed.

Miscellaneous Movement Disorders

Hemifacial spasm is a relatively common disorder in which irregular tonic and clonic movements involve the muscles of one side of the face innervated by the ipsilateral seventh cranial nerve. Unilateral eyelid twitching usually is the first symptom, followed at variable intervals by lower-facial muscle involvement. Rarely, the spasm affects both sides of the face, in which case the spasms are asynchronous on the two sides, in contrast to other pure facial dyskinesias such as cranial dystonia (Wu et al., 2010).

Another disorder in which movements are secondary to the subjective need to move is the restless legs syndrome, perhaps the most common of all movement disorders, occurring in approximately 14% of women and 7% of men older than 50 years of age (Trenkwalder and Paulus, 2010). Unlike in akathisia, the patient with restless legs syndrome typically complains of a variety of sensory disturbances in the legs, including pins and needles, creeping or crawling, aching, itching, stabbing, heaviness, tension, burning, and coldness. Occasionally, similar symptoms occur in the arms. These complaints usually are experienced during recumbency in the evening and often are associated with insomnia. This condition commonly is associated with another movement disorder, periodic leg movements of sleep, sometimes inappropriately called nocturnal myoclonus. These periodic slow, sustained (1- to 2-second) movements range from synchronous or asynchronous dorsiflexion of the big toes and feet to triple flexion of one or both legs. More rapid myoclonic movements or slower, prolonged, dystonic-like movements of the feet and legs also may be present in these patients while awake, and these too may have a natural periodicity. Leg myoclonus or foot dystonia may also be the presenting feature of the stiff person syndrome.

Some dyskinesias occur intermittently rather than persistently. This is typical of tics and certain forms of myoclonus. Dystonia often occurs only with specific actions, but this is usually a consistent response to the action rather than a periodic and unpredictable occurrence. Some patients with dystonia have a diurnal variation (dopa-responsive dystonia) characterized by essentially normal motor function in the morning with emergence or worsening of dystonia as the day progresses, so that by the end of the day the patients are unable to ambulate because of severe generalized dystonia. A small group of patients with chorea or dystonia have bouts of sudden-onset, short-lived, involuntary movements known as paroxysmal choreoathetosis or, more appropriately, paroxysmal dyskinesia (Box 21.10). Certain features such as precipitants, duration, frequency, age of onset, and family history (see Chapter 71) characterize these disorders and sometimes help to separate them into diagnostic categories. Thus, paroxysmal dyskinesias may be categorized as kinesigenic (precipitated by voluntary movement such as arising from a chair or starting to run), nonkinesigenic, exertional, or nocturnal. In many cases, the movements are so infrequent that the physician never sees them, so a careful history is needed to determine the nature of the disorder, and having the patient provide a videotape of the events is often invaluable. There may be a family history of seizures or migraines. Increasing number of paroxysmal dyskinesias are being recognized as genetic channelopathies or mitochondrial disorders (Ghezzi et al., 2009). The glucose transporter-1 (GLUT-1) deficiency syndrome often results in paroxysmal exercise-induced dyskinesia as well as other clinical features (Leen et al., 2010; Pons et al., 2010). Periodic ataxias often are included in the group of paroxysmal movement disorders.

Box 21.10 Classification of Paroxysmal Dyskinesias

Finally, psychogenic movement disorders characterized by abnormal slowness or excessive movements or postures that cannot be directly attributed to a lesion or an organic dysfunction in the nervous system are emerging as one of the most common groups of disorders encountered in movement disorder clinics (Gupta and Lang, 2009; Thomas and Jankovic, 2010). Derived primarily from psychiatric or psychological disorders, because of their rich spectrum of phenomenology and variable severity, psychogenic movement disorders present a major diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Facilitating the diagnosis of psychogenic movement disorders are various clues that include somatic and psychiatric complaints and movement disorders whose phenomenology is incongruous with typical movement disorders. These include sudden onset (often related to some emotional or minor physical trauma), secondary gain, variable frequency of tremor, distractibility, and exaggeration of symptoms (Box 21.11).

Investigation of Movement Disorders

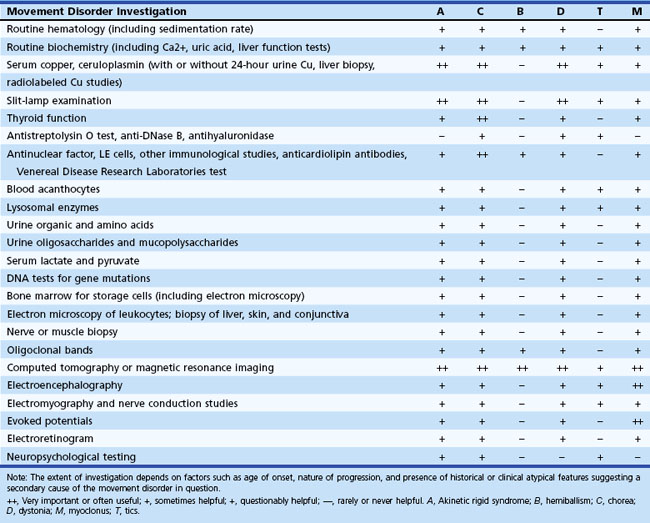

The importance of excluding WD cannot be overemphasized. This includes slit-lamp examination, measurement of serum ceruloplasmin and copper, liver function tests, measurement of 24-hour urinary copper excretion and, if necessary, liver biopsy and genetic testing. Children, adolescents, and young adults presenting with parkinsonism, chorea, or a dystonic or myoclonic syndrome need additional careful hematological and biochemical assessment, as indicated in Table 21.5.

Although in the majority of movement disorders, the diagnosis depends on recognizing typical clinical phenomena, diagnosis of certain movement disorders requires blood tests. Neuroacanthocytosis usually presents in adolescence or early adulthood with chorea, dystonia, tics, and progressive weakness; diagnosis requires demonstrating blood acanthocytes, elevated serum creatine kinase, and altered nerve conduction studies (Walker et al., 2006). Biochemical screening may also reveal evidence of hypoparathyroidism, which can cause calcification of the basal ganglia, resulting in several movement disorders. Hyperthyroidism, polycythemia rubra vera, and SLE are common enough causes of undiagnosed chorea in an adult to necessitate exclusion in all cases. Early clues are a history of recurrent fetal loss, a prolonged partial thromboplastin time, a false-positive VDRL (Venereal Disease Research Laboratories) test, and thrombocytopenia, which indicates the presence of antiphospholipid immunoglobulins such as the lupus anticoagulant and anticardiolipin antibodies. Consider Sydenham chorea in a child presenting with chorea of unknown origin, and obtain antistreptolysin O titer, antihyaluronidase, and electrocardiogram. In a patient with hemiballism, one should search for potential risk factors for vascular disease by measuring levels of blood sugar, hemoglobin, platelets, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, cholesterol, and triglycerides.