Chapter 324 Motility Disorders and Hirschsprung Disease

324.1 Chronic Intestinal Pseudo-Obstruction

Clinical Manifestations

The diagnosis of pseudo-obstruction is based on the presence of compatible symptoms in the absence of anatomic obstruction. Plain abdominal radiographs demonstrate air-fluid levels in the small intestine. Neonates with evidence of obstruction at birth have a microcolon. Contrast studies demonstrate slow passage of barium; water-soluble agents should be considered. Esophageal motility is abnormal in about half the patients. Antroduodenal motility and gastric emptying studies have abnormal results if the upper gut is involved (Table 324-1). Manometric evidence of a normal migrating motor complex and postprandial activity should redirect the diagnostic evaluation. Anorectal motility is normal and differentiates pseudo-obstruction from Hirschsprung disease. Full-thickness intestinal biopsy might show involvement of the muscle layers or abnormalities of the intrinsic intestinal nervous system.

| GI SEGMENT | FINDINGS* |

|---|---|

| Esophageal motility | Abnormalities in approximately half of CIPO, although in some series up to 85% demonstrate abnormalities |

| Decreased LES pressure | |

| Failure of LES relaxation | |

| Esophageal body: low-amplitude waves, poor propagation, tertiary waves, retrograde peristalsis, occasionally aperistalsis | |

| Gastric emptying | May be delayed |

| ECG | Tachygastria or bradygastria may be seen |

| ADM | Postprandial antral hypomobility is seen and correlates with delayed gastric emptying |

| Myopathic subtype: low-amplitude contractions, <10-20 mm Hg | |

| Neuropathic subtype: contractions are uncoordinated | |

| Fed response is absent | |

| Fasting MMC is absent, or MMC is abnormally propagated | |

| Colonic | No gastric reflex because there is no increased motility in response to a meal |

| ARM | Normal rectoanal inhibitory reflex (RAIR) |

ADM, antroduodenal manometry; ARM, anorectal manometry; CIPO, chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction; EGG, electrogastrography; GI, gastrointestinal; LES, lower esophageal sphincter; MMC, migrating motor complex.

* Findings can vary according to the segment(s) of the gastrointestinal tract that are involved.

From Wyllie R, Hyams JS, editors: Pediatric gastrointestinal and liver disease, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2006, Saunders.

Cucchiara S, Borrelli O, Salvia G, et al. A normal gastrointestinal motility excludes chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction in children. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:258-264.

Di Nardo G, Blandizzi C, Volta U, et al. Review article: molecular, pathological and therapeutic features of human enteric neuropathies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:25-42.

Haftel LT, Lev D, Barash V, et al. Familial mitochondrial intestinal pseudo-obstruction and neurogenic bladder. J Child Neurol. 2000;15:386-389.

Iyer K, Kaufman S, Sudan D, et al. Long-term results of intestinal transplantation for pseudo-obstruction in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:174-177.

Lapointe SP, Rivet C, Goulet O, et al. Urological manifestations associated with chronic intestinal pseudo-obstructions in children. J Urol. 2002;168:1768-1770.

Mousa H, Hyman PE, Cocjin J, et al. Long-term outcome of congenital intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:2298-2305.

Venkatasubramani N, Sood M. Motility disorders of the gastrointestinal tract. Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2006;73:927-930.

Walker WA, Goulet O, Kleinman R, et al. Pediatric gastrointestinal disease, ed 4. Hamilton, Ontario: BC Decker; 2004.

324.2 Functional Constipation

Constipation is defined by a delay or difficulty in defecation present for 2 weeks or longer and significant to cause distress to the patient. Another approach to the definition is noted in Table 324-2. Functional constipation, also known as idiopathic constipation or fecal withholding, can usually be differentiated from constipation secondary to organic causes on the basis of a history and physical examination (Chapter 21.4). Unlike anorectal malformations and Hirschsprung disease, functional constipation typically starts after the neonatal period. Usually, there is an intentional or subconscious withholding of stool. An acute episode usually precedes the chronic course. The acute episode may be a dietary change from human milk to cow’s milk, secondary to the change in protein:carbohydrate ratio or an allergy to cow’s milk. The stool becomes firm, smaller, and difficult to pass, resulting in anal irritation and often an anal fissure. In toddlers, coercive or inappropriately early toilet training is a factor that can initiate a pattern of stool retention. In older children, retentive constipation can develop after entering a situation that makes stooling inconvenient such as school. Because the passage of bowel movements is painful, voluntary withholding of feces to avoid the painful stimulus develops.

Table 324-2 CHRONIC CONSTIPATION: ROME III CRITERIA

INFANTS AND TODDLERS

At least 2 of the following:

CHILDREN WITH A DEVELOPMENTAL AGE OF 4-18 YEARS

At least 2 of the following:

From Carvalho RS, Michail SK, Ashai-Khan F, et al: An update in pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition: a review of some recent advances, Curr Prob Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 38:197–234, 2008.

Therapy for functional constipation includes patient education, relief of impaction, and softening of the stool (Chapter 21.4). The parents must understand that soiling associated with overflow incontinence is associated with loss of normal sensation and not a willful act. A regular bowel training program, including sitting on the toilet for 5-10 min after meals and keeping track of the frequency of bowel movements, is often helpful in establishing a regular bowel habit. If an impaction is present on the initial physical examination, an enema is usually required to clear the impaction while bowel softeners are started as maintenance medications. Typical regimens include the use of polyethylene glycol preparations, lactulose, or mineral oil. Prolonged use of stimulants such as senna or bisacodyl should be avoided. Children with behavioral problems that are interfering with successful treatment might benefit from a referral to a mental heath care provider. Maintenance therapy is generally continued until a regular bowel pattern has been established and the association of pain with the passage of stool is abolished. Children with spinal problems can be successfully managed with low volumes of fluid through a cecostomy or sigmoid tube.

Bekkali NLH, van den Berg MM, Dijkgraaf MGW, et al. Rectal fecal impaction treatment in childhood constipation: enemas versus high doses oral PEG. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e1108-e1115.

Camilleri M, Kerstens R, Rykx A, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of prucalopride for severe chronic constipation. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2344-2354.

Candy D, Belsey J. Macrogol (polyethylene glycol) laxatives in children with functional constipation and faecal impaction: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:156-160.

Carvalho RS, Michail SK, Ashai-Khan F, et al. An update in pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition: a review of some recent advances. Curr Prob Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2008;38:197-234.

Hutson J, McNamara J, Shin Y. Review article: slow transit constipation in children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2001;37:426-430.

Emmanuel AV, Kamm MA. Response to a behavioral treatment, biofeedback, in constipated patients is associated with improved gut transit and autonomic innervation. Gut. 2001;49:214-219.

Masi P, Miele E, Staiano A. Pediatric anorectal disorders. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2008;37:709-730.

Pijpers M, Tabbers M, Benninga M, et al. Currently recommended treatments of childhood constipation are not evidence based: a systematic literature review on the effect of laxative treatment and dietary measures. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:117-131.

Rosen R, Buonomo C, Andrade R, et al. Incidence of spinal cord lesions in patients with intractable constipation. J Pediatr. 2004;145:409-411.

Van de Berg M, Benninga M, DiLorenzo C. Epidemiology of childhood constipation: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2401-2409.

Van Dijk M, Benninga M, Grootenhuis M, et al. Chronic childhood constipation: a review of the literature and the introduction of a protocolized behavioral intervention program. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67(1–2):63-77.

Walker WA, Goulet O, Kleinman R, et al. Pediatric gastrointestinal disease, ed 4. Hamilton, Ontario: BC Decker; 2004.

324.3 Congenital Aganglionic Megacolon (Hirschsprung Disease)

Clinical Manifestations

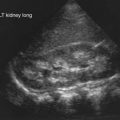

Hirschsprung disease in older patients must be distinguished from other causes of abdominal distention and chronic constipation (Table 324-3 and Fig. 324-1). The history often reveals constipation starting in infancy that has responded poorly to medical management. Fecal incontinence, fecal urgency, and stool-withholding behaviors are usually not present. The abdomen is tympanitic and distended, with a large fecal mass palpable in the left lower abdomen. Rectal examination demonstrates a normally placed anus that easily allows entry of the finger but feels snug. The rectum is usually empty of feces, and when the finger is removed, there may be an explosive discharge of foul-smelling feces and gas. The stools, when passed, can consist of small pellets, be ribbon-like, or have a fluid consistency, unlike the large stools seen in patients with functional constipation. Intermittent attacks of intestinal obstruction from retained feces may be associated with pain and fever. Urinary retention with enlarged balder or hydronephrosis can occur secondary to urinary compression.

Table 324-3 DISTINGUISHING FEATURES OF HIRSCHSPRUNG DISEASE AND FUNCTIONAL CONSTIPATION

| VARIABLE | FUNCTIONAL | HIRSCHSPRUNG DISEASE |

|---|---|---|

| HISTORY | ||

| Onset of constipation | After 2 yr of age | At birth |

| Encopresis | Common | Very rare |

| Failure to thrive | Uncommon | Possible |

| Enterocolitis | None | Possible |

| Forced bowel training | Usual | None |

| EXAMINATION | ||

| Abdominal distention | Uncommon | Common |

| Poor weight gain | Rare | Common |

| Rectum | Filled with stool | Empty |

| Rectal Examination | Stool in rectum | Explosive passage of stool |

| Malnutrition | None | Possible |

| INVESTIGATIONS | ||

| Anorectal manometry | Relaxation of internal anal sphincter | Failure of internal anal sphincter relaxation |

| Rectal biopsy | Normal | No ganglion cells, increased acetylcholinesterase staining |

| Barium enema | Massive amounts of stool, no transition zone | Transition zone, delayed evacuation (>24 hr) |

Diagnosis

An unprepared contrast enema is most likely to aid in the diagnosis in children older than 1 mo because the proximal ganglionic segment might not be significantly dilated in the first few weeks of life. Classic findings are based on the presence of an abrupt narrow transition zone between the normal dilated proximal colon and a smaller-caliber obstructed distal aganglionic segment. In the absence of this finding, it is imperative to compare the diameter of the rectum to that of the sigmoid colon, because a rectal diameter that is the same as or smaller than the sigmoid colon suggests Hirschsprung disease. Radiologic evaluation should be performed without preparation to prevent transient dilatation of the aganglionic segment. As many as 10% of newborns with Hirschsprung disease have a normal contrast study. Twenty-four hour delayed films are helpful in showing retained contrast (Fig. 324-2). If significant barium is still present in the colon, it increases the suspicion of Hirschsprung disease even if a transition zone is not identified. Barium enema examination is useful in determining the extent of aganglionosis before surgery and in evaluating other diseases that manifest as lower bowel obstruction in a neonate. Full-thickness rectal biopsies can be performed at the time of surgery to confirm the diagnosis and level of involvement.

Bonnard A, Zeidan S, Degas V, et al. Outcomes of Hirschsprung’s disease assocated with Mowat-Wilson syndrome. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:587-591.

Dasgupta R, Langer J. Hirschsprung disease. Curr Probl Surg. 2004;41:942-988.

Dasgupta R, Langer J. Evaluation and management of persistent problems after surgery for Hirschsprung disease in a child. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46(1):13-19.

DeLorijn F, Reitsma JB, Voskuijl WP, et al. Diagnosis of Hirschsprung’s disease: a prospective comparative accuracy study of common tests. J Pediatr. 2005;146:787-792.

Hackam D, Reblock K, Barksdale E, et al. The influence of Down’s syndrome on the management and outcome of children with Hirschsprung’s disease. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:946-949.

Haricharan R, Georgeson K. Hirschsprung disease. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2008;17:266-275.

Keshtgar AS, Ward HC, Clayden GS, et al. Investigations for incontinence and constipation after surgery for Hirschsprung’s disease in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2003;19:4-8.

Langer JC, Durrant AC, de la Torre L, et al. One-stage transanal Soave pull through for Hirschsprung disease: a multicenter experience with 141 children. Ann Surg. 2003;238:569-583. discussion 583–585

Pensabene L, Youssef NN, Griffiths JM, et al. Colonic manometry in children with defecatory disorders. Role in diagnosis and management. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1052-1057.

Prato AP, Musso M, Ceccherini I, et al. Hirschsprung disease and congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT). Medicine. 2009;88:83-90.

Walker WA, Goulet O, Kleinman R, et al. Pediatric gastrointestinal disease, ed 4. Hamilton, Ontario: BC Decker; 2004.

324.4 Intestinal Neuronal Dysplasia

Management includes that for functional constipation and, if unsuccessful, surgery is indicated.

Hutson J, McNamara J, Shin Y. Review article: slow transit constipation in children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2001;37:426-430.

Kapur R. Neuropathology of paediatric chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction and related animal models. J Pathol. 2001;194:277-288.

Montedonico S, Acevedo S, Fadda B. Clinical aspects of intestinal neuronal dysplasia. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37(12):1772-1774.

Walker WA, Goulet O, Kleinman R, et al. Pediatric gastrointestinal disease, ed 4. Hamilton, Ontario: BC Decker; 2004.