36

Morphea and Lichen Sclerosus

Morphea (Localized Scleroderma)

• It is distinct from systemic sclerosis (SSc; see Chapter 35) in that morphea is not associated with sclerodactyly, Raynaud’s phenomenon, nailfold capillary abnormalities, or internal organ involvement.

• Morphea does not transition into SSc, except for a few rare case reports.

• Equal prevalence in adults and children; more common in females and Caucasians.

• Classified based on clinical presentation, with five major variants recognized (see Fig. 35.1; Table 36.1).

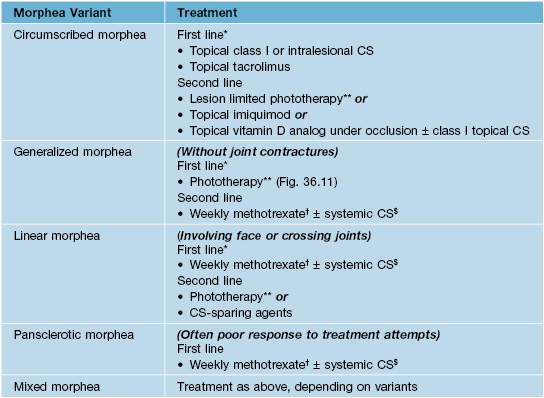

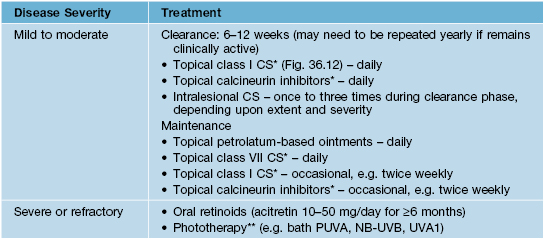

Table 36.1

Approach to the treatment of morphea.

Treatment is most effective in active, inflammatory lesions. Topical monotherapy should not be used if any of the following are present: progressing functional impairment, joint contractures or involvement across joints, linear facial involvement.

* If not improved after ~8 to 10 weeks, progress to next line of therapy.

** Phototherapy choice based on local availability (BB-UVA, UVA1, NB-UVB, PUVA); NB-UVB more effective for superficial lesions and UVA1 more effective for deeper lesions.

† Weekly methotrexate doses: adults, 15–25 mg/week; children, 0.3–0.4 mg/kg/week.

$ Especially for early/progressive lesions; pulsed > daily dosing.

BB-UVA, broadband ultraviolet A light phototherapy; UVA1, narrowband ultraviolet A light phototherapy; NB-UVB, narrowband ultraviolet B light phototherapy; PUVA, psoralens plus ultraviolet A light phototherapy.

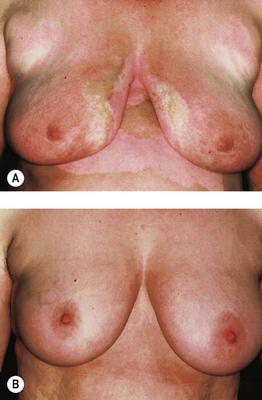

Fig. 36.11 Phototherapy of generalized morphea. Generalized morphea with trunk involvement before (A) and after PUVA bath photochemotherapy (B). Note that generalized morphea may involve the breasts but characteristically spares the nipples. Courtesy, Martin Rocken, MD, and Kamran Ghoreschi, MD.

• Early morphea lesions present as erythematous to violaceous patches and plaques (Fig. 36.1); they then evolve into sclerotic (often ivory-colored), hairless, anhidrotic plaques with variable degrees of dyspigmentation (Fig. 36.2).

Fig. 36.1 Early inflammatory circumscribed morphea (morphea en plaque) of the trunk. Early stage lesion presenting as an erythematous edematous plaque. Courtesy, Martin Rocken, MD, and Kamran Ghoreschi, MD.

Fig. 36.2 Mid to later stage circumscribed morphea (morphea en plaque). Multiple, large hyperpigmented plaques, several of which have an inflammatory border.

• Circumscribed (plaque) morphea is the most common variant in adults, presenting with ≤3 discrete indurated plaques; the latter favor the trunk and tend to develop in areas of pressure (e.g. hips, waist, and bra line in women); superficial and deep variants (morphea profunda) exist (Fig. 36.3).

Fig. 36.3 Comparison of deep morphea and eosinophilic fasciitis. A Note the ‘pseudo-cellulite’ appearance of the involved skin of the thigh in deep morphea. B In eosinophilic fasciitis, the level of fibrosis is also deep, resulting in a similar clinical appearance.

• Generalized morphea is a rare variant that presents with >3 indurated plaques larger than 3 cm and/or involving ≥2 body sites; spares the face and hands (see Fig. 36.11); more likely to have a (+) ANA and systemic symptoms.

• Linear morphea is the most common variant in children and may cause a significant degree of morbidity because of ocular involvement and occasionally CNS involvement in the head variant (Fig. 36.4) or muscle atrophy, discrepancies in limb length, and joint contractures in the limb variant (Fig. 36.5).

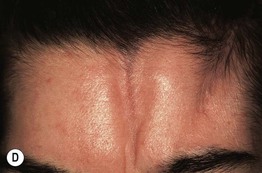

Fig. 36.4 Linear morphea, head variant. A Parry–Romberg syndrome, demonstrating hyperpigmentation and loss of subcutaneous tissue, leading to facial asymmetry. B–D En coup de sabre with linear paramedian depressions and sclerosis – (B) (wide) and (C) (narrow) – being more common than midline involvement as in (D). Note the prominent veins and loss of the medial eyebrow in (B). A and C, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD; D, Courtesy, Martin Rocken, MD, and Kamran Ghoreschi, MD.

Fig. 36.5 Linear morphea, limb variant. A Linear morphea involving the leg; the differential diagnosis includes linear melorheostosis, which is associated with underlying candlewax-like linear hyperostosis. B Extensive induration of the left leg with hypoplasia and an obvious flexion contracture of the knee; there is also involvement of the right foot. C Linear distribution of coalescing sclerotic plaques on the thigh; note the lilac-colored border. B, Courtesy, Martin Rocken, MD, and Kamran Ghoreschi, MD; C, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• Extracutaneous manifestations are most common in patients with generalized morphea and in children; arthralgia is the most common finding.

• DDx: morpheaform disorders (Table 36.2; see Table 35.4), SSc, lichen sclerosus, keloids (Fig. 36.6), atrophoderma of Pasini and Perini.

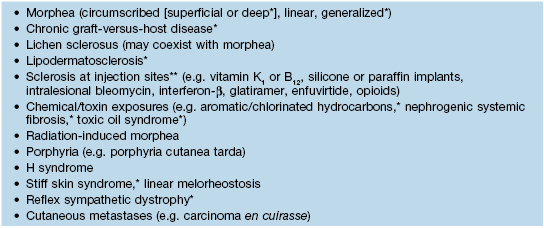

Table 36.2

Differential diagnosis of morpheaform skin lesions.

The location of the morpheaform lesions may offer a clue to the diagnosis, e.g. in lipodermatosclerosis lesions are located on the lower extremities, and in radiation-induced morphea lesions are within the radiation port site.

* Can overlap with sclerodermoid disorders, which are outlined in Table 35.4; in particular, deep morphea and eosinophilic fasciitis may have a similar appearance (see Fig. 36.3).

** Systemic medications for which there have been reports of an association with morpheaform lesions include bleomycin, taxanes (e.g. paclitaxel, docetaxel), bromocriptine, ethosuximide, valproic acid, appetite suppressants, and penicillamine.

Fig. 36.6 Nodular (keloidal) morphea. Elevated, firm pink papulonodules arising within an area of hyperpigmented induration. Courtesy, Jean Bolognia, MD.

• Morphea and SSc cannot be differentiated by histopathologic examination.

• Rx: best utilized during the early, inflammatory stage (see Table 36.1); in general, therapy will not readily reverse established sclerosis; however, the truncal plaques of circumscribed and generalized morphea often soften over a period of years, eventually resembling atrophoderma or completely resolving.

Lichen Sclerosus (LS)

• Formerly called lichen sclerosus et atrophicus.

• Most commonly affects female or male genitalia, less often nongenital skin.

• Approximately 80% of LS patients have IgG autoantibodies against extracellular matrix (ECM-1).

• Ultrapotent topical corticosteroids are highly effective for treatment of LS (see Fig. 36.12); other treatment options are listed in Table 36.3.

Table 36.3

Treatment options for lichen sclerosus (LS).

Some clinicians limit the use of calcineurin inhibitors for genital LS.

* Ointments are preferred over creams for genital LS because they are less irritating.

** Not recommended for genital LS because increases risk of genital SCC.

PUVA, psoralens plus ultraviolet A light phototherapy; NB-UVB, narrowband ultraviolet B light phototherapy; UVA1, narrowband ultraviolet A light phototherapy.

Genital LS in Females

• Bimodal presentation: 6th–7th decade and 8–13 years of age.

• Early: well-demarcated, erythematous thin plaque; ± erosions (Fig. 36.7).

Fig. 36.7 Genital lichen sclerosus involving the vulva of a young female. Centrally, there is erythema with superficial erosion and purpura. More peripherally, white plaques with a wrinkled surface are seen. Note fissuring of the perineum. Courtesy, Martin Rocken, MD, and Kamran Ghoreschi, MD.

• Mid: evolves into dry, hypopigmented sclerotic lesion.

• Purpura and perineal fissures are common findings and sometimes mistaken for sexual abuse.

• Associated symptoms: severe pruritus, soreness, dysuria, dyspareunia, and pain upon defecation.

• May be complicated by possible SCC development.

• DDx: vitiligo, erosive lichen planus, sexual abuse, intraepithelial neoplasia (see Chapter 60), SCC, extramammary Paget’s disease.

Genital LS in Males

• Also known as balanitis xerotica obliterans.

• Bimodal presentation: older males and prepubertal males; more common if uncircumcised.

• Often presents with recurrent balanitis or acquired phimosis; rarely affects perianal region.

• Early: glans and inner foreskin have well-demarcated, erythematous thin plaques; ± erosions.

• Mid: evolves into atrophic, white, sclerotic, scar-like lesion (Fig. 36.8).

Fig. 36.8 Genital lichen sclerosus involving the penis (balanitis xerotica obliterans). Note the ivory color, erosion, and scarring.

• Late: phimosis or complete occlusion of glans.

• DDx: SCC in situ, sexual abuse, erosive lichen planus, candidiasis, intraepithelial neoplasia (see Chapter 60), extramammary Paget’s disease.

Extragenital LS

• Affects all ages with slight female predominance.

• Favors the neck (Fig. 36.9), shoulders, trunk, proximal extremities, flexor wrists, and sites of trauma or pressure; associated xerosis and mild pruritus.

Fig. 36.9 Extragenital lichen sclerosus (LS). LS of the neck presenting as white papules and small plaques (A) and as a large, shiny, ivory-colored plaque of the lower back (B). Courtesy, Martin Rocken, MD, and Kamran Ghoreschi, MD.

• Early: polygonal, white, shiny, elevated papules that often coalesce into plaques.

• Mid: evolve into scar-like, atrophic, wrinkled patches and plaques.

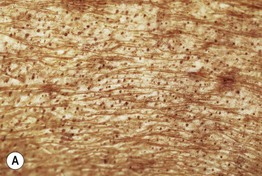

• Late: telangiectasias, follicular plugging (Fig. 36.10A), and occasional hemorrhagic bullae (Fig. 36.10B).

Fig. 36.10 Extragenital lichen sclerosus (LS). A Follicular plugging in a plaque of LS on the back of a patient with chronic GVHD. B Hemorrhagic bullae on the leg. A, Courtesy, Jean Bolognia, MD.

• DDx: localized morphea, scar; of note, LS may coexist with morphea and/or vitiligo.

For further information see Ch. 44. From Dermatology, Third Edition.