65 Mononeuropathies of the Upper Extremities

Mononeuropathies of the Shoulder Girdle

Dorsal Scapular Neuropathies

Clinical Vignette

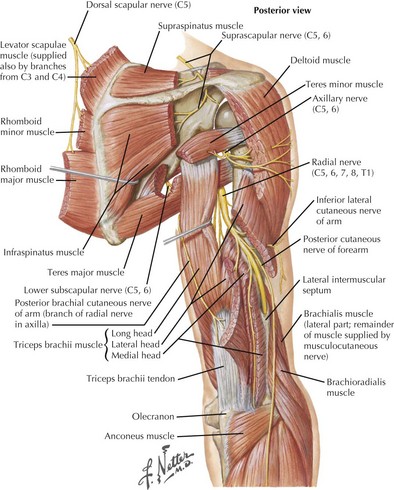

The dorsal scapular nerve receives fibers from the C5 nerve root. It innervates the levator scapulae and the rhomboideus major and minor muscles, which assist in stabilization of the scapula, rotation of the scapula in a medial–inferior direction, and elevation of the arm (Fig. 65-1). Rhomboid weakness can lead to scapular winging, which is most prominent when the patient raises the arm overhead. Possible etiologies of injury to this nerve include shoulder dislocation, weightlifting, and entrapment by the scalenus medius muscle.

Long Thoracic Neuropathies

Clinical Vignette

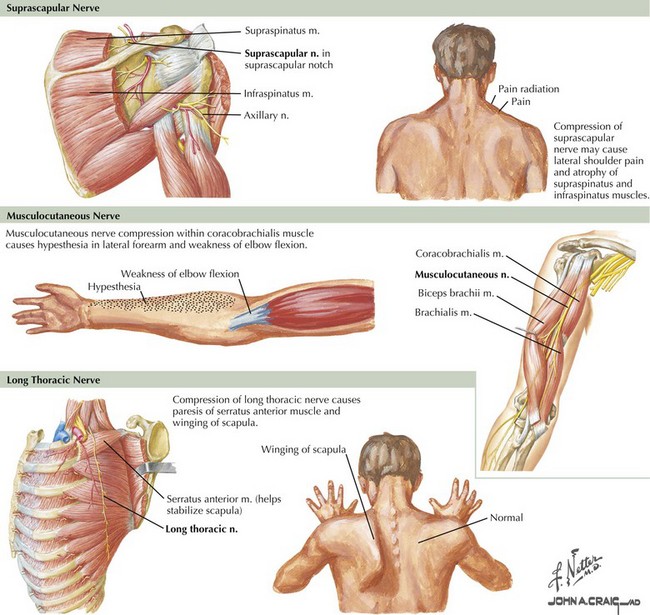

The long thoracic nerve originates directly from C5–C7 roots, before the formation of the brachial plexus. It innervates the serratus anterior muscle and has no cutaneous sensory representation (Fig. 65-2). Weakness of the serratus anterior is debilitating, because it stabilizes the scapula for pushing movements and elevates the arm above 90 degrees. This is the most common cause of scapular winging; it is best recognized by having the patient push against a wall. The inferior medial border is the most prominently projected away from the body wall. A dull shoulder ache may accompany this neuropathy. When severe acute pain occurs with the onset of scapular winging, brachial plexus neuritis should be considered.

Suprascapular Neuropathies

Clinical Vignette

The suprascapular nerve emerges from the upper trunk of the brachial plexus, receiving fibers from C5 and C6 roots. It does not have any cutaneous innervation. The suprascapular nerve first provides innervation to the supraspinatus muscle, a shoulder abductor, and then to the infraspinatus, a shoulder external rotator (see Fig. 65-1). The suprascapular nerve may be injured at the suprascapular notch, before the innervation of the supraspinatus muscle, or distally at the spinoglenoid notch, affecting the infraspinatus alone (see Fig. 65-2). The most common site of entrapment is at the suprascapular notch, under the transverse scapular ligament. Acute-onset cases result from blunt shoulder trauma, with or without scapular fracture, or from forceful anterior rotation of the scapula. The suprascapular nerve may also be affected by brachial plexus neuritis in isolation or with other nerves. Suprascapular neuropathies of insidious onset often occur subsequent to callous formation after fractures, from entrapment at the suprascapular or spinoglenoid notch, by compression from a ganglion or other soft tissue mass, or by traction caused by repetitive overhead activities such as volleyball or tennis.

Axillary Neuropathies

Clinical Vignette

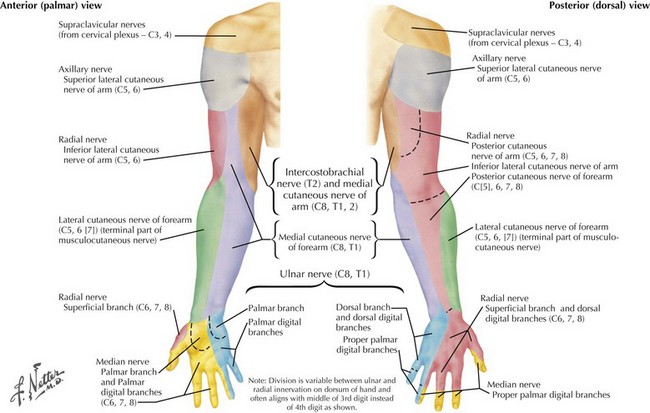

The axillary nerve, along with the radial nerve, is a terminal branch of the posterior cord of the brachial plexus. It innervates the deltoid and the teres minor and provides sensory innervation to the lateral upper part of the shoulder via the superior lateral brachial cutaneous nerve of the arm (Figs. 65-1 and 65-3). In lesions of the axillary nerve, shoulder abduction is weakened and cutaneous sensibility of the lateral shoulder diminishes, overlapping the C5 dermatome. Because the teres minor is not the predominant external rotator of the shoulder, clinical isolation and testing are difficult. EMG may be necessary to define neurogenic injury to this muscle. Most axillary neuropathies are traumatic, related to anterior shoulder dislocations, humerus fractures, or both. Recognition of nerve injury may be delayed because of the shoulder injury. Acute axillary neuropathies can result from blunt trauma or as a component or sole manifestation of brachial plexus neuritis.

Musculocutaneous Neuropathies

Clinical Vignette

The musculocutaneous nerve originates directly from the lateral cord of the brachial plexus. It innervates the coracobrachialis, biceps brachii, and brachialis muscles and terminates in its cutaneous branch, the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve. Isolated musculocutaneous neuropathies are rare. They have been reported in weight lifters, after surgery, and after prolonged pressure during sleep. Damage to the musculocutaneous nerve results in weakness of forearm flexion and supination and sensory loss of the lateral volar forearm (see Fig. 65-2). The biceps reflex is diminished, but the brachioradialis reflex (same myotome, different nerve) is preserved. More commonly, injury to this nerve occurs as part of a more widespread traumatic injury, usually involving the proximal humerus. The musculocutaneous nerve can also be preferentially involved in acute brachial plexus neuritis. Distal lesions of the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve may result from attempted cannulation of the basilic vein in the antecubital fossa. Rupture of the biceps tendon is a significant differential diagnostic consideration of musculocutaneous neuropathy.

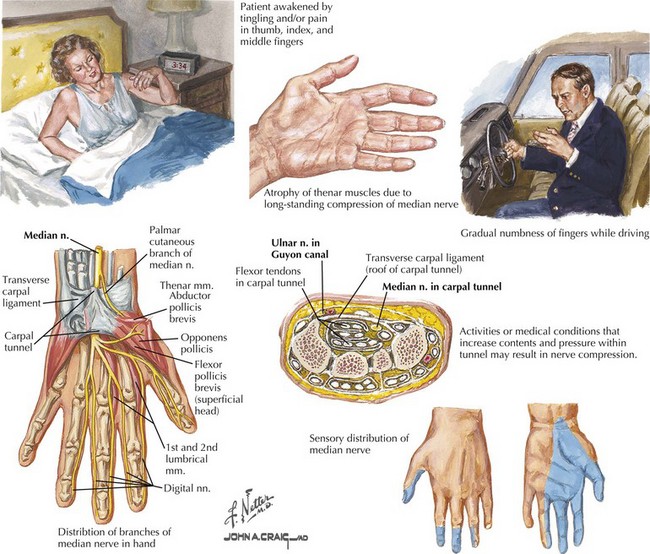

Median Mononeuropathies

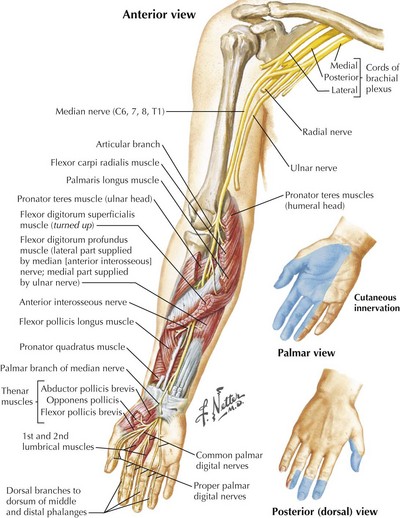

The anatomy of the median nerve is important in understanding the signs and symptoms of entrapment lesions at the level of the wrist, versus the more proximal lesions. The median nerve provides essential motor and sensory function to the lateral aspect of the hand (Fig. 65-4). It supplies the intrinsic hand muscles of most of the thenar eminence and innervates several forearm muscles. Its major sensory role is to provide innervation for the thumb, index, and middle fingers and the lateral half of the ring finger.

Distal Median Entrapment

Clinical Presentation and Testing

Median nerve entrapment at the wrist commonly presents with intermittent symptoms, including pain and paresthesias in the hand and forearm. The symptoms tend to occur on awakening or at night, and they are often provoked by certain postures or activities such as reading or driving (Fig. 65-5). The perception that paresthesias may affect all digits (rather than just the lateral three and a half innervated by the median nerve) is likely related to the greater cortical representation of the thumb and first two fingers. As CTS progresses, persistent numbness ensues, alerting the patient that the precise sensory distribution involves the volar surface of the first three and a half digits. The neurologic examination, particularly in mild CTS cases, may offer few clues. It is helpful in severe cases, in which atrophy of the thenar eminence is common. Median hand functions, primarily thumb abduction and opposition, are weak. Having the patient supinate the forearm so the palm is flat, and then raise the thumb vertically against resistance, tests the abductor pollicis brevis muscle. Forearm muscles supplied by the median nerve proximal to the flexor retinaculum are spared in CTS.

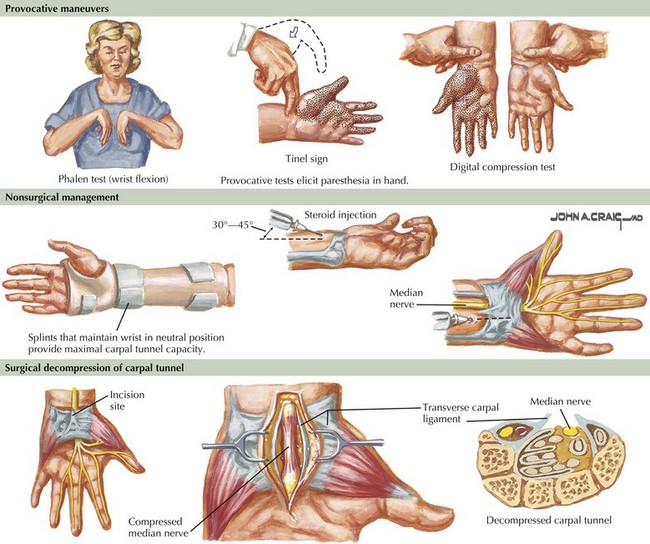

Provocative tests offer supportive but not diagnostic evidence in suspected CTS (Fig. 65-6). A positive Tinel sign consists of an electric, shooting sensation (not just local discomfort) radiating into the appropriate digits with wrist percussion. Tinel and Phalen maneuvers (reproduction of paresthesias on forceful flexion of the wrist) should be performed with nonleading questions to improve response credibility. It is recommended that the Phalen maneuver be maintained for at least 1 minute before determining that the result is negative. The pressure test may be the most reliable of the three maneuvers; pressure is placed over the carpal tunnel (proximal palm, not wrist) for 20–30 seconds, attempting to reproduce paresthesias in a median nerve distribution.

Management

Surgical decompression is offered to patients with increasingly annoying sensory symptoms and progressive abnormalities on neurologic examination and electrophysiological testing (see Fig. 65-6). Although published success rates vary significantly, the average surgical success rate is 75%; 8% of patients may worsen after surgery. Long duration of symptoms, increasing age, and the presence of workers compensation claims appear to be associated with poorer outcome. Patients with moderate electrophysiological abnormalities appear to do best, and the success rate of surgery in the absence of nerve conduction abnormalities is only 51%. Occasionally, patients present with end-stage CTS and absent motor responses on nerve conduction studies. Resolution of pain is the only realistic goal of surgical intervention for these patients. Meaningful return of thenar strength is less likely this late in the course of the neuropathy. Endoscopic techniques are being used in carpal tunnel decompression but the relative benefit of this technique compared with traditional decompressive surgery is not known.

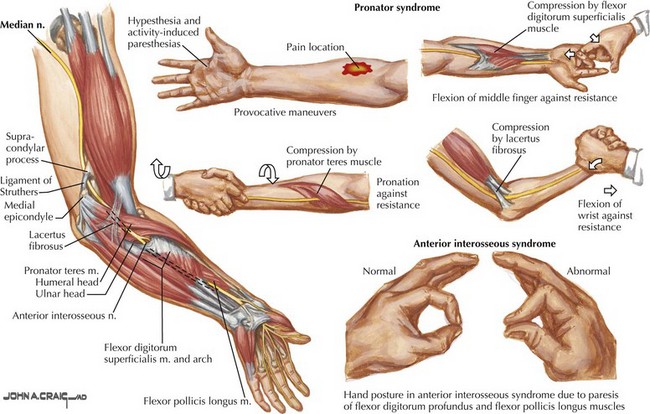

Proximal Median Neuropathies

Clinical Vignette

The clinical and electrophysiologic recognition of weakness in the distribution of the forearm muscles innervated by the median nerve is the diagnostic key (Fig. 65-7). When the median nerve lesion is most proximal, the pronator teres muscle is involved and may be atrophied. Clinical features also include pain in the volar forearm exacerbated by physical activity. There is weakness of thenar muscles and sensory loss in the thumb, index finger, long finger, and lateral aspect of the ring finger.

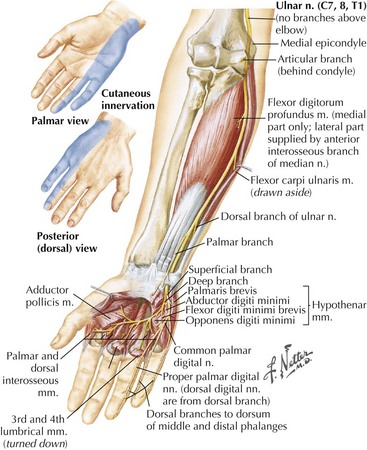

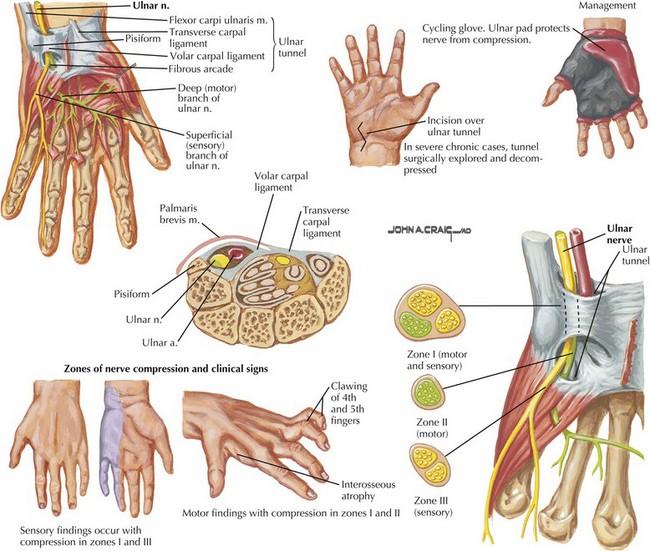

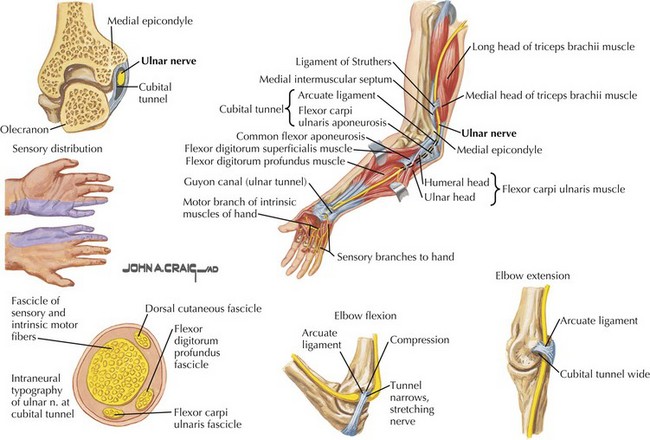

Ulnar Mononeuropathies

The ulnar nerve primarily innervates intrinsic hand muscles, including all hypothenar muscles (Fig. 65-8). The muscles of the thenar eminence supplied by the ulnar nerve are the adductor pollicis and part of the flexor pollicis brevis. Only two forearm muscles have ulnar innervation, the flexor carpi ulnaris and the medial part of the flexor digitorum profundus. The ulnar nerve also supplies sensation to the medial one and a half fingers (the medial aspect of digits 4 and 5), on the dorsal surface sometimes the medial two and a half fingers (see Figs. 65-3 and 65-8). Manifestations of ulnar neuropathies vary with location and severity. Progressive motor deficits lead to the classic “claw hand,” with hyperextension of the fourth and fifth metacarpophalangeal joints and flexion of the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints (Fig. 65-9). This is most pronounced when the patient is asked to open the hand because of the unopposed action of radial nerve–innervated muscles. Similar to its median counterpart, the ulnar nerve is typically affected at two anatomic loci, the elbow and wrist, however, in reverse frequency. The majority of ulnar nerve lesions occur at the elbow (Fig. 65-10).

Proximal Lesions

Clinical Vignette

Electrodiagnostic testing showed a demyelinating left ulnar neuropathy at the elbow.

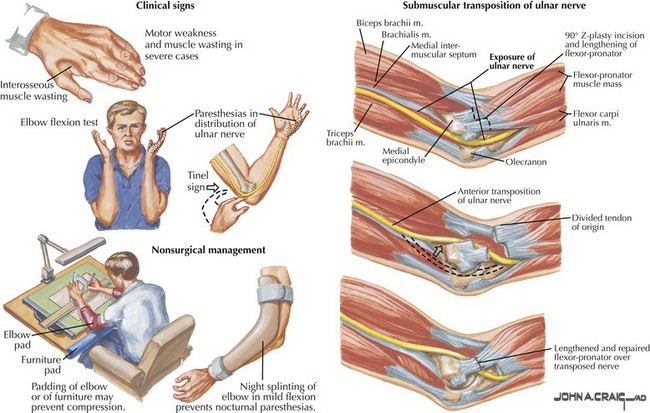

Proximal ulnar neuropathies are second only to CTS in frequency. Etiologies include external compression or entrapment at the elbow after remote elbow trauma (tardy ulnar palsy), and entrapment just distal to the elbow joint (cubital tunnel syndrome, Fig. 65-11).

Distal Lesions

Clinical Vignette

Ulnar neuropathies at the level of the wrist or palm are less common than proximal lesions. The nerve might become entrapped at the level of the ulnar tunnel or the Guyon canal. Common causes are trauma, ganglion cysts, rheumatoid arthritis, and wrist fractures. Depending on the exact site of injury, there may or may not be associated sensory symptoms (see Fig. 65-9). Sensory loss on the dorsal aspect of the medial hand points to a more proximal ulnar neuropathy with involvement of the dorsal ulnar cutaneous nerve.

Management

Conservative treatment consists of avoiding the stretch produced by a fully flexed elbow via a padded splint that prevents further direct nerve pressure. More than 50% of patients with mild nerve compression might recover with conservative therapy, although data on long-term outcome is limited. Surgical management of ulnar lesions is not as well defined as with CTS. It is even less clear who is likely to benefit from surgery, and there is no consensus on which surgical procedure is appropriate. Persistent pain, progressive motor deficits, and to a lesser extent failure to improve after 3–6 months of conservative management are reasons to consider surgery. Once sensory ulnar nerve conductions can no longer be obtained, recovery of sensory function after surgery becomes less likely. With tardy ulnar palsy, surgeons typically transpose the nerve away from the offending epicondylar groove, often with concomitant epicondylectomy (see Fig. 65-11). This procedure is associated with some risk, particularly in patients with diabetes, because the microvasculature of the nerve can be easily compromised. For cubital tunnel lesions in the absence of trauma or prior surgical procedure involving the elbow, anterior transposition seems to offer no advantage over simple decompression of the nerve.

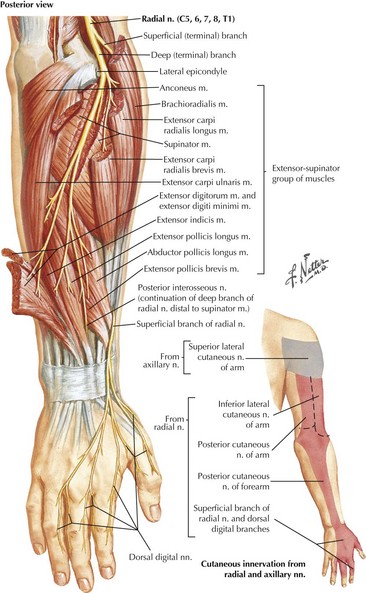

Radial Neuropathies

Clinical Vignette

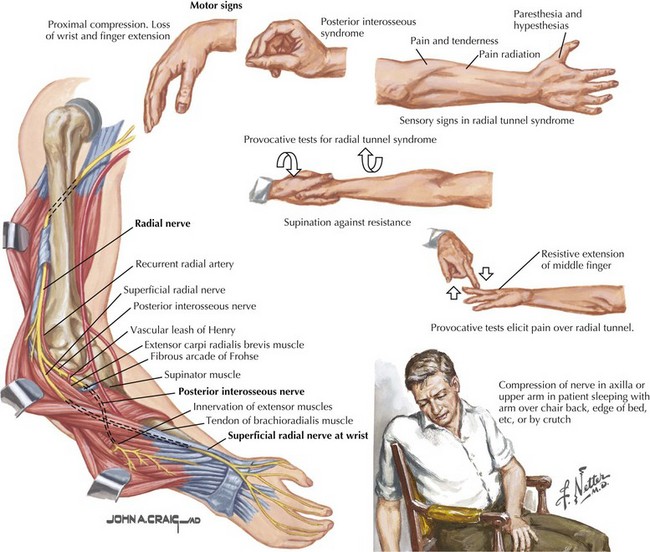

The radial nerve is formed by fibers from all three trunks of the brachial plexus, hence from roots C5 to T1. It primarily supplies the extensor muscles of the arm, forearm, and fingers and one flexor of the arm, the brachioradialis (see Fig. 65-1). It also provides the sensory innervation to the dorsal arm, the dorsolateral aspect of the hand, and the dorsum of the first three and a half, sometimes two and a half fingers (Fig. 65-12).

Predominant Motor Radial Neuropathies

Radial neuropathies most commonly occur at the midhumeral level near the spiral groove, secondary to external compression (Fig. 65-13). This can occur as a result of impaired consciousness during anesthesia or due to drug or alcohol intoxication (“Saturday night palsy”). These lesions primarily present with wrist and finger drop but little or no pain. Sensory signs and symptoms are often elusive. Elbow extension is spared because the branches of the triceps originate proximal to the spiral groove. The brachioradialis reflex is typically diminished or lost, whereas the triceps and biceps reflexes are unaffected. A potentially confounding examination feature is apparent weakness of ulnar innervated finger abduction that appears concomitant with wrist drop. The full strength of these ulnar muscles requires at least partial wrist extension. Testing the strength of finger abduction while placing the hand and forearm flat on a hard and flat surface circumvents this problem and prevents false localization.

Mononeuropathies of the Medial and Posterior Cutaneous Nerves of the Forearm

Isolated injuries of the medial cutaneous nerve of the forearm are rare (see Fig. 65-3). Sensory symptoms in the medial volar forearm are more commonly a result of more proximal injuries to the lower trunk or medial cord of the brachial plexus or to the C8 nerve root. Nerve injuries at these levels are associated with additional clinical findings, particularly hand weakness. Sensory symptoms on the posterior forearm from isolated injuries to the posterior cutaneous nerve of the forearm are equally rare.

Diagnostic Approach to Mononeuropathies

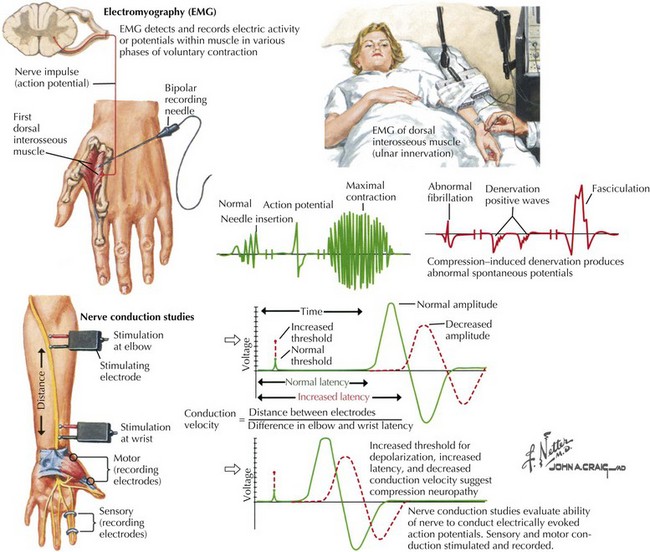

EMG and Nerve Conduction Studies

The various mononeuropathies do not have identical pathophysiologic signatures. Some, such as CTS, are initially characterized by focal slowing (Fig. 65-14), whereas others may preferentially produce a demyelinating conduction block, such as an ulnar neuropathy at the elbow, or axon loss as with a primary laceration, or a combination of the above.

American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine. Available at Accessed June 13 http://www.aanem.org, 2011. The information on this website includes a list of suggested reading for physicians as well as educational material for patients with various neuromuscular disorders

Bland JDP. Do nerve conduction studies predict the outcome of carpal tunnel syndrome? Muscle Nerve. 2001;24:935-940. This study examines factors influencing the outcome of surgical carpal tunnel decompression

Bland JDP. Treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome. Muscle Nerve 2007;36:167-171. This review article summarizes the current knowledge about different treatment modalities for carpal tunnel syndrome

Dumitru D, Amato A, Zwarts M. Electrodiagnostic Medicine, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Hanley&Belfus; 2002. This textbook is an excellent reference for physicians interested in disorders of the peripheral nervous system and electrophysiological techniques

Marshall S, Tardif G, Ashworth N. Local corticosteroid injection for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007;Issue 2. Art. No.: CD001554. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001554.pub2. This article reviews data from 12 randomized or quasi-randomized studies regarding the effectiveness of local corticosteroid injection for carpal tunnel syndrome

O’Connor D, Marshall S, Massy-Westropp N. Non-surgical treatment (other than steroid injection) for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2003; Issue 1. Art. No.: CD003219. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003219. This review article evaluates the effectiveness of conservative treatment options (other than corticosteroid injection) for carpal tunnel syndrome based on data from 21 randomized or quasi-randomized studies

Padua L, Padua R, Aprile I, et al. Multiperspective follow-up of untreated carpal tunnel syndrome. A multicenter study. Neurology. 2001;56:1459-1466. The authors evaluate the natural history of untreated carpal tunnel syndrome over a 10-15 month follow-up period

Scholten RJPM, Mink van der Molen A, Uitdehaag BMJ, et al. Surgical treatment options for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007;Issue 4. Art. No.: CD003905. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003905.pub3. The authors compare the outcome of various surgical techniques for carpal tunnel syndrome, including data from 33 randomized controlled trials

Sunderland S. Nerves and Nerve Injuries, 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone; 1978. This outstanding textbook provides a detailed description of the anatomy and physiology of peripheral nerves and outlines the various mechanisms of nerve injury in great depth

Verdugo RJ, Salinal RS, Castillo J, et al. Surgical versus non-surgical treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2003;Issue 3. Art. No.: CD001552. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001552. The authors summarize two randomized controlled trials comparing surgical treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome with splinting and pool data from both trials for secondary outcomes

Zlowodzki M, Chan S, Bhandari M, et al. Anterior transposition compared with simple decompression for treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg A 2007;89:2591-2598. This meta-analysis of four randomized controlled trials compares the efficacy of simple decompression with anterior transposition of the ulnar nerve in compression neuropathies at the elbow