66 Mononeuropathies of the Lower Extremities

Sciatic Neuropathies

Clinical Vignette

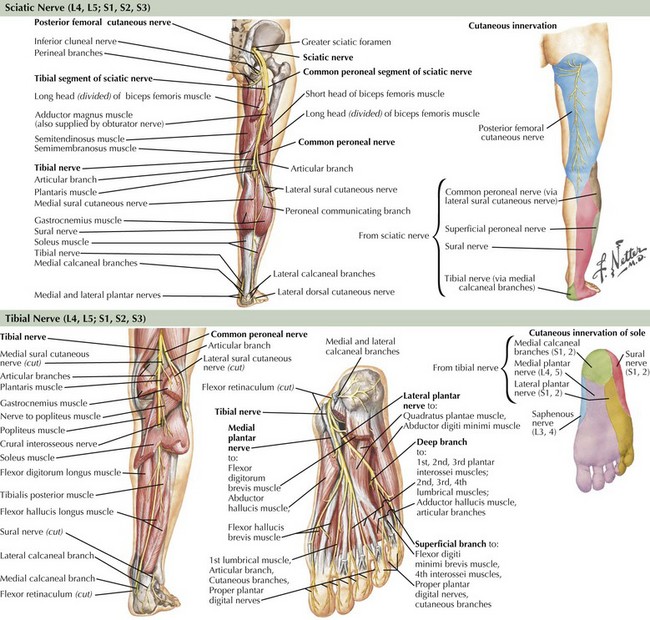

The sciatic nerve is the body’s largest nerve, receiving contributions primarily from the L5, S1, and S2 nerve roots, but also carrying L4 and S3 fibers (Fig. 66-1). It has two primary divisions: the laterally situated more superficial peroneal nerve and the more medially placed tibial nerve (see Fig. 66-1). These separate into two distinct nerves in the mid- to distal thigh. The sciatic nerve and its branches innervate the hamstrings (biceps femoris, semimembranosus, and semitendinosus muscles), distal adductor magnus, anterior and posterior lower leg compartments, and intrinsic foot musculature. Through sensory branches of the tibial nerve (sural, medial and lateral plantar, and calcaneal) and the superficial peroneal nerve, the sciatic nerve also supplies sensation to the skin of the entire foot and the lateral and posterior lower leg.

Peroneal Neuropathies

Etiology

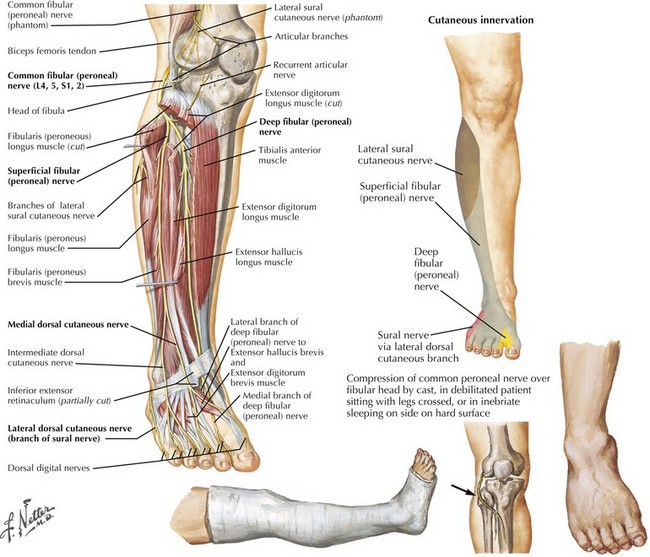

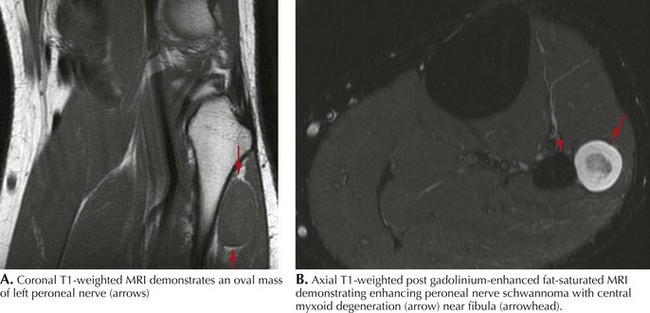

Common peroneal neuropathy is the most frequent lower extremity mononeuropathy. The common peroneal nerve is most susceptible to external compression at the fibular head, where it is very superficial (Fig. 66-2). Predisposing causes include recent substantial weight loss, habitual leg crossing, or prolonged squatting. External devices such as casts, braces, and tight bandages can also cause peroneal neuropathy. Diabetes mellitus, vasculitis, and rarely hereditary tendency to pressure palsy (HNPP) are other etiologic conditions. An acute anterior or lateral compartment syndrome below the knee can also lead to acute common, deep, or superficial peroneal neuropathies. Patients with insidious onset and progressive course require evaluation for mass lesions, including a Baker cyst or ganglion, osteoma, or schwannoma (Fig. 66-3). The common peroneal nerve is sometimes injured iatrogenically. Knee positioning and padding to decrease pressure on the peroneal nerve in the operating room and intensive care unit are important to prevent an acute compression neuropathy. Rarely, laceration of the peroneal nerve occurs with arthroscopic knee repair or direct penetrating trauma.

Clinical Presentation

Most peroneal neuropathies involve the common peroneal nerve at the fibular head causing weakness of foot dorsiflexion and eversion (see Fig. 66-1). Ambulation reveals a “steppage gait” with compensatory hip and knee flexion in order to lift the foot off the floor. The foot might hit the floor with a slap, as the patient has poor control over its movements. With the less frequently occurring deep peroneal neuropathies, there is weakness of the tibialis anterior, extensor hallucis, extensor digitorum longus, and extensor digitorum brevis. Primary superficial peroneal neuropathies cause weakness of the peroneus longus and brevis muscles, which are mainly responsible for foot eversion.

Tibial Neuropathies

Clinical Vignette

Tibial nerve fibers arise primarily from L5, S1 and S2 nerve roots with some contributions from L4 and S3. The tibial nerve leaves the sciatic nerve in the mid- to distal thigh (see Fig. 66-1). The medial sural cutaneous nerve comes off in the popliteal fossa and joins the lateral sural cutaneous nerve (a branch of the common peroneal nerve) in the distal calf to form the sural nerve, which supplies the skin of the lateral aspect of the foot and the posterior lower leg to a variable degree. After innervating the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles, the nerve travels distally between the tibialis posterior and gastrocnemius muscles. It sends branches to the tibialis posterior, flexor digitorum longus, and flexor hallucis longus before entering the tarsal tunnel under the flexor retinaculum. Here, the tibial nerve typically divides into the medial plantar, lateral plantar, and medial calcaneal nerves. Although the medial calcaneal nerve is a purely sensory branch to the medial heel, the medial and lateral plantar nerves are mixed nerves innervating the intrinsic foot muscles as well as the skin of the sole.

Proximal Lesions

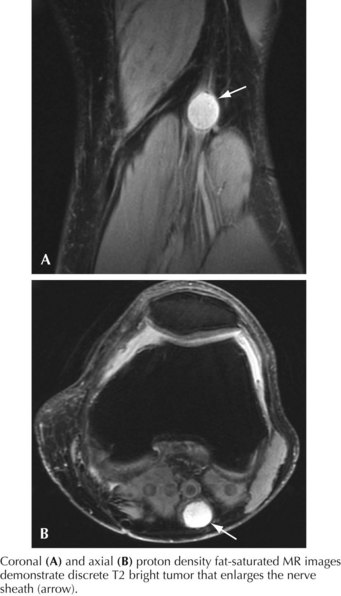

Proximal tibial neuropathies may result from Baker’s cysts, ganglia, tumors (Fig. 66-4), or rarely indirectly from severe ankle strains, the latter presumably resulting from traction injury. They rarely occur in isolation. They are characterized by weakness of foot plantar flexion and inversion; although flexion, abduction, and adduction of the toes may be affected, these latter functions are difficult to evaluate clinically. The ankle jerk is absent if the neuropathy occurs proximal to the branch points of the gastrocnemius-soleus complex. Sensory loss occurs on the heel and plantar foot surface.

Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome

Tarsal tunnel syndrome (TTS), a distal tibial neuropathy, presents primarily with sensory symptoms. It is classified as an entrapment neuropathy of the posterior tibial nerve and of its primary branches, the medial and lateral plantar nerves, at the ankle (See Fig. 66-3). Although well described, there is controversy regarding its prevalence as electrophysiological documentation is infrequent. Whether this reflects its uncommon occurrence or the inadequate sensitivity of diagnostic procedures is unclear. Fractures, ankle sprain, foot deformities due to rheumatoid arthritis or other conditions, varicose veins, tenosynovitis and fluid retention have been implicated as possible etiologies. Patients typically present with burning pain and numbness on the sole of one or both feet. Symptoms may occur while weight bearing and are often exacerbated at night. In well-established instances, examination may disclose intrinsic plantar surface muscle atrophy. However, weakness of these muscles is difficult to appreciate because the more proximal long toe flexors in the leg mask weakness from the involved short toe flexors within the foot. Toe abduction weakness occurs early but is difficult to assess even in healthy individuals. Sensory loss is confined to the sole of the foot; there is sparing of the lateral foot (sural distribution), the dorsum of the foot (peroneal territory), and the instep (saphenous nerve). Muscle stretch reflexes are unaffected. A Tinel sign elicited from the tibial nerve at the ankle is supportive, although not confirmatory.

Femoral Neuropathies

Clinical Vignette

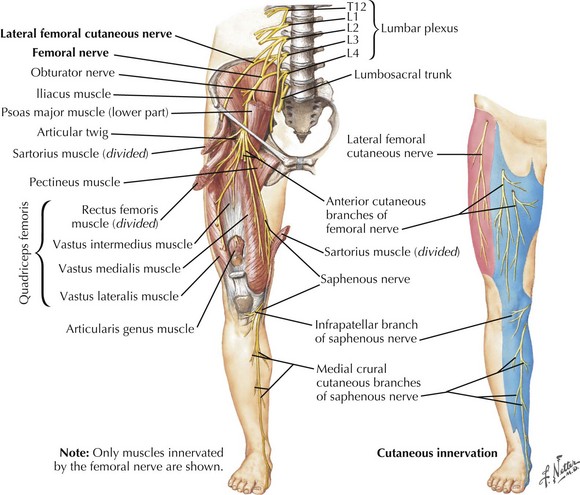

The femoral nerve comes off the lumbar plexus and is formed by the posterior divisions of the L2–L4 roots (Fig. 66-5). It travels between two important hip flexors, the iliopsoas and iliacus muscles, which it innervates. Approximately 4 cm proximal to the inguinal ligament, the femoral nerve is covered by a tight fascia at the iliopsoas groove. It exits the pelvis by passing beneath the medial inguinal ligament to enter the femoral triangle just lateral to the femoral artery and vein. Here, the nerve separates into the anterior and posterior divisions. The anterior division innervates the sartorius muscle and the anteromedial skin of the thigh via the medial cutaneous nerve of the thigh. The posterior division gives off muscular branches to the pectineus and quadriceps femoris muscles as well as the saphenous nerve, a cutaneous branch to the skin of the inner calf. The nerve can be compressed anywhere along its course, but it is particularly susceptible within the body of the psoas muscle, at the iliopsoas groove, and at the inguinal ligament.

Etiology

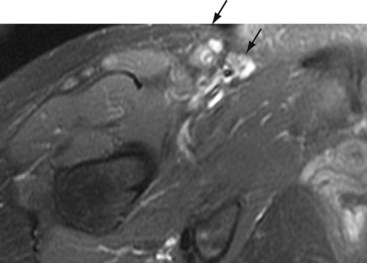

Femoral neuropathies occasionally follow prolonged surgeries or childbirth in the lithotomy position, presumably from anatomic predisposition to kinking beneath the inguinal ligament. Iliacus hematoma or abscess, misplaced attempts at femoral artery or vein puncture, or iatrogenic injury after nephrectomy or hip arthroplasty are other recognized causes. Tumors, benign and malignant, may rarely cause femoral neuropathy (Fig. 66-6). Isolated saphenous nerve injuries may result from knee arthroscopy, femoral–popliteal artery bypass surgery, and in the course of coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

Lateral Femoral Cutaneous Neuropathy

Clinical Vignette

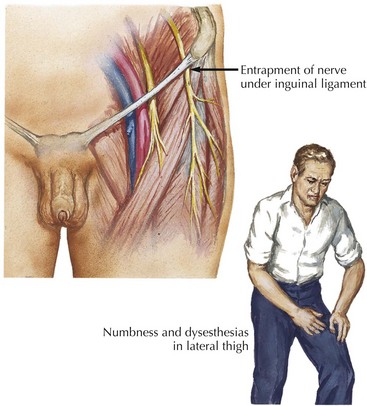

The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN) arises from the second and third lumbar roots and travels through the retroperitoneum. After traversing the psoas muscle, the nerve reaches the iliacus muscle (see Fig. 66-4). Medial to the anterior superior iliac spine, it exits the pelvis under or through the inguinal ligament, the presumed usual site of entrapment. Subsequently, it supplies sensation to the anterolateral thigh.

Etiology

Meralgia paresthetica is an entrapment mononeuropathy of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (Fig. 66-7). Cadaver studies suggest that meralgia paresthetica is primarily an entrapment neuropathy due to “kinking” of the nerve as it passes through the inguinal ligament. Like many mononeuropathies, it is more common in people with diabetes. Meralgia paresthetica often occurs in overweight individuals, especially after sudden gain in weight, or in individuals wearing tight belts and garments. It is usually unilateral. Occasionally, the nerve is injured within the thigh secondary to blunt or penetrating trauma (e.g., a misplaced injection), or rarely, by a soft tissue sarcoma within the thigh.

Obturator Neuropathies

Clinical Vignette

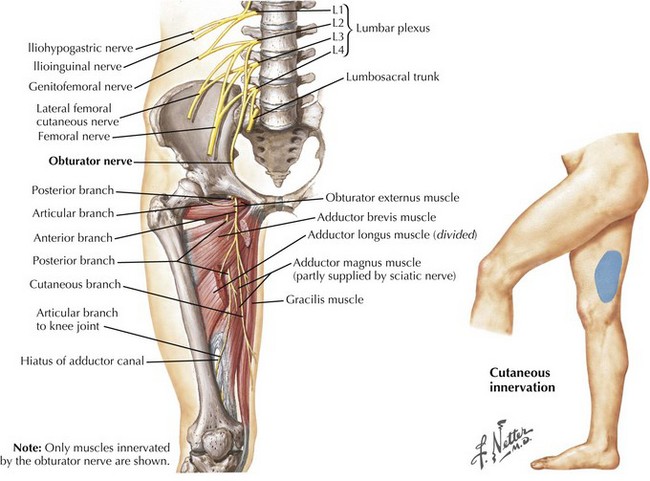

The obturator nerve originates from the anterior rami of the L2, L3, and L4 nerve roots (Fig. 66-8). After its course through the pelvis, the nerve exits through the obturator canal and separates into the anterior and posterior divisions. The anterior division supplies the adductor longus, adductor brevis and gracilis muscles, whereas its terminal branch provides sensation to the distal medial thigh. The posterior division innervates the obturator externus, the superior portion of the adductor magnus, and sometimes the adductor brevis.

Iliohypogastric, Ilioinguinal, and Genitofemoral Neuropathies

American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine. Available at Accessed July 6 http://www.aanem.org, 2008. The information on this website includes a list of suggested reading for physicians as well as educational material for patients with various neuromuscular disorders

Dumitru D, Amato A, Zwarts M. Electrodiagnostic Medicine, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Hanley&Belfus; 2002. This textbook is an excellent reference for physicians interested in disorders of the peripheral nervous system and electrophysiological techniques

Katirji B. Peroneal neuropathy. Neurol Clin. 1999;17:567-591. The author provides a good review of the clinical presentation and electrophysiology of peroneal nerve lesions

Kuntzer T, van Melle G, Regli F. Clinical and prognostic features in unilateral femoral neuropathies. Muscle Nerve. 1997;20:205-211. This article studies the clinical and electrodiagnostic features influencing outcome in 32 patients with femoral neuropathy

Sorenson EJ, Chen JJ, Daube JR. Obturator neuropathy: causes and outcome. Muscle Nerve. 2002;25:605-607. The authors retrospectively examine the causes and prognoses of obturator neuropathy in 22 patients

Sunderland S. Nerves and Nerve Injuries, 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone; 1978. This outstanding textbook provides a detailed description of the anatomy and physiology of peripheral nerves and outlines the various mechanisms of nerve injury in great depth