Chapter 15 Minimally Invasive Cardiac Surgery

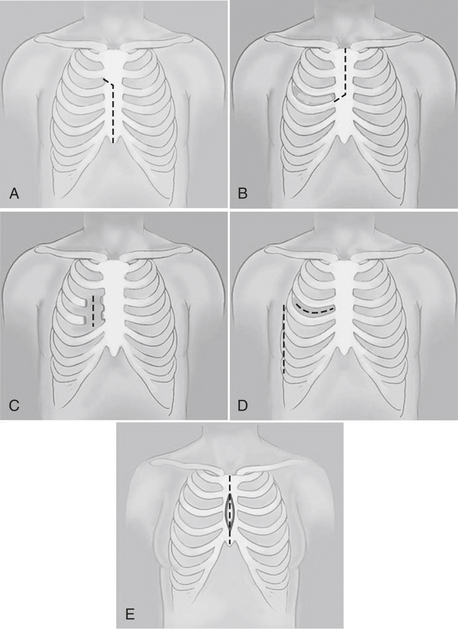

This chapter focuses on the anesthetic implications of operations performed through an incision other than a full sternotomy or thoracotomy and does not address the various endovascular procedures under development. The common incisions used for these procedures are shown in Figure 15-1 and include partial sternotomies (upper vs. lower, unilateral vs. bilateral) and minithoracotomies (anterior vs. anterolateral vs. posterolateral, nonspreading vs. spreading) in addition to totally endoscopic procedures done exclusively through thoracoscopic ports (defined as < 15 mm).

GENERAL ANESTHETIC CONSIDERATIONS

Patient Setup

Position, Prepping, and Draping

Conventional cardiac surgery is almost always performed with the patient flat and supine, prepped, and draped with the sterile field extending from mid-neck to the ankles (Box 15-1). Many MICS procedures, however, require different positions and sterile field setups. For example, most procedures performed through anterior minithoracotomies or exclusively thoracoscopically are done with the patient’s left or right side elevated approximately 30 degrees. Some thoracoscopic procedures are performed in the left or right lateral decubitus position, typically with the hips rotated to expose one or both groins for possible femoral vascular cannulation. Unlike conventional sternotomy procedures, surgical access to remote areas (neck, lateral chest wall, groin) may be necessary for peripheral cannulation, placement of camera/instrument ports, or transcutaneous retraction sutures. This should be taken into consideration when placing ECG leads or other items on the skin during setup.

Anesthetic Technique

Airway

Carbon dioxide insufflation of the hemithorax is frequently used during thoracoscopic MICS procedures, especially during robotic procedures. Insufflation to a pressure of 8 to 15 cm H2O can dramatically increase the working space in the chest by shifting the mediastinal structures posteriorly and to the contralateral chest. Because there is always some obligatory leak around ports and incisions, the constant flow of CO2 also clears smoke generated during electrocauterization of tissues. The intrathoracic pressure should be set to the minimal value necessary to achieve adequate exposure, and very careful monitoring of hemodynamics and gas exchange is essential, because the physiology is effectively that of a controlled tension pneumothorax. Although generally well tolerated, significant hypotension, hypercapnia, or hypoxia can occur if the pressure is set too high, particularly in patients with ventricular dysfunction or lung disease.1

Anesthetic Regimen

Because accelerated recovery and discharge are major goals of MICS, it is important to note that careful selection of the anesthetic agents is necessary to ensure that the patient obtains the full benefit from the minimally invasive approach. Most centers will use some sort of “fast-track” anesthesia regimen—typically very short-acting narcotics and muscle relaxants in conjunction with an inhalation agent.2 Some have advocated precise pharmacokinetically controlled total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) regimens. Routine intraoperative extubation of MICS patients is controversial. Although some centers have established protocols whereby nearly all patients are extubated at the completion of the procedure,3 others have argued that a clinical or economic benefit is difficult to document unless the patient recovers in a postoperative acute care unit setting without an overnight stay in the intensive care unit.4

Pain Management

Aggressive pain management is another critical component of the care of patients undergoing MICS, without which it is difficult to obtain the full benefit of this approach. Successful pain management permits intraoperative or early postoperative extubation, early ambulation, and discharge. There is some evidence that the amount of pain in the early postoperative period may not be significantly less in many types of MICS and that it may actually be higher in some, particularly those involving rib-spreading thoracotomies. The pain, however, seems to dissipate more rapidly than with full sternotomy; most patients are off narcotic pain medicines within 1 or 2 weeks of surgery.5

Spinal/Epidural Anesthesia

Spinal and epidural anesthetics have been used as an adjunct to general anesthesia at many institutions practicing MICS. A single intrathecal dose of a long-acting narcotic can be beneficial in reducing intraoperative and postoperative parenteral or enteral narcotic requirements.6 A thoracic epidural catheter with narcotic or local anesthetics can be administered continuously or with patient-controlled dosing.7 The excellent pain control and potential cardioprotective benefits from this approach, however, are mitigated by the additional operative time, the small but finite additional risk from the epidural anesthesia, and its potential to delay the typically rapid mobilization and discharge of MICS patients.

GENERAL CARDIOPULMONARY BYPASS CONSIDERATIONS

Although nearly all minimally invasive coronary artery bypass surgery is performed on a beating heart, without the use of CPB, minimally invasive surgery of the cardiac valves and other intracardiac structures requires creative and innovative techniques to safely establish CPB (Box 15-2). There are a variety of approaches depending on the incision and access to cardiovascular structures. Some minimally invasive approaches permit direct, central cannulation similar to conventional cardiac surgery but typically with relatively small cannulae and vacuum-assisted venous drainage. On the other end of the spectrum, “Port-Access” techniques, pioneered by Heartport, Inc. (Redwood City, CA) in the early 1990s, sought to have all elements of the CPB circuit enter peripherally, preferably percutaneously, to allow procedures to be performed through very small incisions or totally endoscopically. The anesthesiologist plays a central role in all “Port-Access” procedures from insertion of certain cannulae to monitoring cannula position and function by TEE.8

MINIMALLY INVASIVE CORONARY ARTERY BYPASS GRAFTING

The goals of minimally invasive coronary artery bypass grafting are to reduce the surgical trauma by minimizing access and to obviate the need for extracorporeal circulation (Box 15-3). These procedures encompass minimally invasive direct coronary artery bypass grafting (MIDCAB), totally endoscopic coronary artery bypass grafting on an arrested or beating heart, and multivessel small thoracotomy revascularization.

Minimally Invasive Direct Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting

The main advantages of the MIDCAB procedure are the avoidance of CPB and median sternotomy, potentially less postoperative pain, and faster recovery to normal activities. Studies showed good short-term patency rates of the LIMA-to-LAD anastomosis.9

Totally Endoscopic Coronary Artery Revascularization

Totally Endoscopic Coronary Artery Bypass on the Arrested Heart

The most frequently performed procedure using this technique to date is revascularization of the LAD with the LIMA via a left-sided approach.10 The RCA can also be grafted with the RIMA via a right-sided approach.

Totally Endoscopic Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting on the Beating Heart

The development of endoscopic CABG on the beating heart required the development of endoscopic stabilizers and methods for temporary coronary occlusion. Vascular occlusion can be achieved by using vascular clamps or Silastic bands. For this procedure, the patient is prepared as described earlier. In addition to the three left-sided ports, an endoscopic epicardial stabilizer is inserted through a subxiphoid port after harvest and preparation of the LIMA. Endoscopic stabilizers use combined pressure and suction stabilization to facilitate the performance of the anastomosis. Because the heart is not decompressed with this technique, the space in the thoracic cavity is limited despite CO2 insufflation. In this particular situation, CO2 pressure may be increased above 12 mmHg if the heart is sufficiently filled and myocardial contractility is adequate. Compared with full-sternotomy beating heart surgery, the myocardial tolerance to ischemia in beating heart totally endoscopic coronary artery bypass grafting (TECAB) is reduced. After occlusion of the target vessel, if severe ST-segment elevation or multiple extrasystoles appear on the ECG, the conversion threshold to MIDCAB should be low.11 The anastomosis is performed with a running suture (7-0 or 8-0 Prolene), interrupted sutures (U-clips), or distal anastomotic devices.

MINIMALLY INVASIVE VALVULAR SURGERY

Valvular procedures such as aortic valve replacement and mitral valve replacement and repair are now performed using different types of minimally invasive procedures (Box 15-4).

Minimally Invasive Aortic Valve Surgery

The Brigham and Women’s Hospital surgeons reported their series of more than 500 mini-invasive aortic valve replacements with an operative mortality of 2% and a freedom from reoperation at 6 years of 99%.12

Minimally Invasive Mitral Valve Surgery

Level 1: Direct-Vision Minimally Invasive Mitral Valve Surgery

The Brigham group published their experience of 1000 minimally invasive valve operations.12 They performed 474 mitral procedures through a lower sternotomy, a right parasternal, or a right thoracotomy incision. They reported excellent results with operative and late mortality rates of 0.2% and 3.0%, respectively, and freedom from reoperation at 6 years was 95%. Compared with patients who had a full sternotomy incision, those who had a minimally invasive approach had shorter CPB and cross-clamp times, fewer myocardial infarctions, fewer pacemaker insertions, and a shorter length of stay (2 days).

Level 2: Video-Assisted and Video-Directed Minimally Invasive Mitral Valve Surgery

Chitwood and colleagues reported their experience with 31 consecutive patients (20 mitral repairs and 11 replacements) with excellent results.13 Thirty-day mortality was 3.2%. No stroke or aortic dissection was reported. Compared with patients who had conventional mitral valve surgery, these patients had significantly shorter hospitalization times, less perioperative pain, and faster recovery. In addition, hospital charges were reduced.

Level 3: Robot-Directed Minimally Invasive Mitral Valve Surgery

In robotically directed MIMVS, a voice-activated system (AESOP 3000; Computer Motion, Inc., Santa Barbara, CA) is attached to the thoracoscope. The motion of the robot is controlled by the surgeon with voice activation and one- or two-word commands. The overall performance of the procedure by allowing a full range of motion and a steady operative field and by decreasing the number of lens cleanings and, hence, operating times. Chitwood’s group published their experience of robotically directed MIMVS with low mortality and morbidity. Seventy percent of the cases were repairs. They reported that the robotically directed technique showed significant decreases in blood loss, ventilator time, and hospitalization compared with the sternotomy-based technique.14

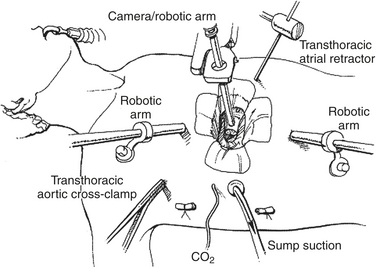

Level 4: Telemanipulation and Computer-Enhanced Minimally Invasive Mitral Valve Surgery

Mitral valve surgery can now be done completely endoscopically using the DaVinci system (Intuitive Surgical, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA). This system has three components: (1) a surgeon console, (2) an instrument cart, and (3) a vision platform. The operative console is removed physically from the patient and allows the surgeon to sit comfortably. The surgeon’s fingers and wrist movements are registered through sensors in computer motor banks, and then these actions are transferred to the instrument cart, which operates synchronous end-effector instruments. A three-dimensional digital visioning system enables natural depth perception with high-power magnification (Fig. 15-2).

Figure 15-2 Typical setup for a robotic mitral valve repair.

(From Kypson AP, Chitwood WR Jr: Robotic mitral valve surgery. Am J Surg 188[4A suppl]:83S, 2004. Copyright 2004, with permission from Excerpta Medica Inc.)

Patients who are good candidates for this kind of procedure are those with isolated degenerative mitral valve disease. Exclusion criteria for robotic mitral valve surgery were described by Kypson and Chitwood and are as follows: previous right thoracotomy, renal failure, liver dysfunction, bleeding disorders, severe pulmonary hypertension (systolic PAP > 60 mmHg), significant aortic or tricuspid valve disease, coronary artery disease requiring surgery, recent myocardial infarction (<30 days), recent stroke (<30 days), and severely calcified mitral valve annulus.15 Patients with poor lung function undergo pulmonary testing to make sure that they can tolerate one-lung ventilation. Should they not be able to tolerate it, CPB is instituted earlier for intrathoracic preparation.

OTHER MINIMALLY INVASIVE CARDIAC PROCEDURES

Congenital Heart Surgery

In pediatric cardiac surgery, current robotic systems have been used primarily to facilitate thoracoscopic pediatric procedures on extracardiac lesions, such as ligation of patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) and division of vascular rings.16 With the present technology, patients weighing less than 15 kg cannot undergo a robotically-assisted surgery because the instruments are too big and occupy the entire ICS of most small infants.

Intracardiac lesion repair had been performed by robotically-assisted surgery in the adult population. Argenziano and associates reported a series of 17 patients (12 secundum-type ASDs and 5 patent foramen ovales [PFOs]). Patients included were aged between 18 and 80 years old and had a Qp:Qs greater than 1.5 or a PFO with a documented neurologic event.17 Patients excluded were those who could not tolerate one-lung ventilation, those with severe peripheral vascular disease, and those with dense right pleural adhesions. They reported no mortality, median aortic cross-clamp and CPB times of 32 and 122 minutes, respectively, and a successful repair rate of 94% (16 of 17). They also reported that this technique hastened postoperative recovery and improved quality of life.18

Surgery for Atrial Fibrillation

Robotic telemanipulation systems have also been used to perform surgery for atrial fibrillation and ventricular resynchronization. Surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation allows elimination of the arrhythmia in two ways: (1) creation of a contiguous encircling lesion around the pulmonary veins that prohibits the propagation of current and future foci of automaticity from the pulmonary veins, and (2) creation of linear lesions in other parts of the atrium designed to interrupt potential macroreentrant circuits.19

SUMMARY

1. Vassiliades T.A.Jr. The cardiopulmonary effects of single-lung ventilation and carbon dioxide insufflation during thoracoscopic internal mammary artery harvesting. Heart Surg Forum. 2002;5:22.

2. Myles P.S., McIlroy D. Fast-track cardiac anesthesia: Choice of anesthetic agents and techniques. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2005;9:5.

3. Lee T.W., Jacobsohn E. Pro: Tracheal extubation should occur routinely in the operating room after cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2000;14:603.

4. Peragallo R.A., Cheng D.C. Con: tracheal extubation should not occur routinely in the operating room after cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2000;14:611.

5. Niinami H., Ogasawara H., Suda Y., et al. Single-vessel revascularization with minimally invasive direct coronary artery bypass: Minithoracotomy or ministernotomy? Chest. 2005;127:47.

6. Parlow J.L., Steele R.G., O’Reilly D. Low dose intrathecal morphine facilitates early extubation after cardiac surgery: Results of a retrospective continuous quality improvement audit. Can J Anaesth. 2005;52:94.

7. Kessler P., Aybek T., Neidhart G., et al. Comparison of three anesthetic techniques for off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting: General anesthesia, combined general and high thoracic epidural anesthesia, or high thoracic epidural anesthesia alone. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2005;19:32.

8. Ceriana P., Pagnin A., Locatelli A., et al. Monitoring aspects during Port-Access cardiac surgery. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 2000;41:579.

9. Mack M.J., Magovern J.A., Acuff T.A., et al. Results of graft patency by immediate angiography in minimally invasive coronary artery surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68:383. discussion 389

10. Wimmer-Greinecker G., Deschka H., Aybek T., et al. Current status of robotically assisted coronary revascularization. Am J Surg. 2004;188(4A suppl):76S.

11. Mierdl S., Byhahn C., Lischke V., et al. Segmental wall motion abnormalities during minimally invasive and endoscopic coronary artery bypass grafting. Anesth Analg. 2005;100:306.

12. Mihaljevic T., Cohn L.H., Unic D., et al. One thousand minimally invasive valve operations: Early and late results. Ann Surg. 2004;240:529. discussion 534

13. Chitwood W.R.Jr., Wixon C.L., Elbeery J.R., et al. Video-assisted minimally invasive mitral valve surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;114:773. discussion 780

14. Felger J.E., Chitwood W.R.Jr., Nifong L.W., et al. Evolution of mitral valve surgery: Toward a totally endoscopic approach. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:1203. discussion 1208

15. Kypson A.P., Chitwood W.R.Jr. Robotic mitral valve surgery. Am J Surg. 2004;188(4A suppl):83S.

16. Suematsu Y., del Nido P.J. Robotic pediatric cardiac surgery. Present and future perspectives. Am J Surg. 2004;188(4A suppl):98S.

17. Argenziano M., Oz M.C., Kohmoto T., et al. Totally endoscopic atrial septal defect repair with robotic assistance. Circulation. 2003;108(suppl II):II-191.

18. Morgan J.A., Peacock J.C., Kohmoto T., et al. Robotic techniques improve quality of life in patients undergoing atrial septal defect repair. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:1328.

19. Garrido M.J., Williams M., Argenziano M. Minimally invasive surgery for atrial fibrillation: Toward a totally endoscopic, beating heart approach. J Card Surg. 2004;19:216.