Metastatic Tumors of the Ovary

General Features

The ovaries are involved by metastatic tumors more often than any other organ in the female genital tract, regardless of the location of the primary neoplasm.1 Tumors that extend to the ovary directly from adjacent organs or tissues are also included in the category of secondary tumors; however, most ovarian carcinomas associated with uterine cancers of similar histologic type are independent primary neoplasms (see Chapter 27).

Metastatic tumors to the ovary are common and occur in approximately 30% of women dying of cancer. About 6–7% of all adnexal masses found during physical examination are actually metastatic ovarian tumors, frequently unsuspected by gynecologists.2–4 The metastasis often masquerades as a primary ovarian tumor and may even be the initial manifestation of the patient’s cancer. Pathologists also tend to mistake metastatic tumors for primary ovarian neoplasms, even after microscopic examination, because the existence of a concurrent or prior tumor in another organ is either not known or disregarded. Also, all metastatic tumors may have a functioning ovarian stroma with clinical or pathologic evidence of hyperestrogenism simulating a primary ovarian tumor.

The frequencies of various sites of origin of secondary ovarian tumors differ among different countries according to the incidence of various cancers therein. Carcinomas of the colon, stomach, breast, and endometrium, as well as lymphomas and leukemias, account for the vast majority of cases.5 Rectal or sigmoid colon cancer accounts for 75% of the metastatic intestinal tumors to the ovary, and probably constitutes the most common cause of misdiagnosis.2–5 The Krukenberg tumor is almost always secondary to a gastric adenocarcinoma, but may occasionally originate in the intestine, appendix, breast, or other sites.3,5,6 Rarely, breast cancer metastatic to the ovary presents clinically as an ovarian mass. In fact, in patients with a history of breast cancer, especially BRCA-positive cases, clinically detected ovarian tumors are usually independent primaries and not metastases. In recent years, attention has been drawn to mucinous tumors of the appendix, pancreas, and biliary tract that often spread to the ovary and closely simulate ovarian mucinous borderline tumors or carcinomas.7–11 Resemblance to borderline tumors or even benign cystadenofibromas is due to the so-called maturation phenomenon by which the epithelium of the metastatic carcinoma differentiates and appears flattened and benign. A wide variety of other tumors may metastasize to the ovary.

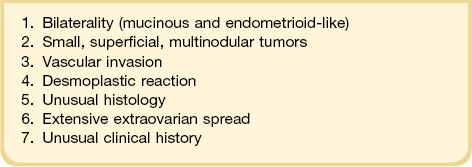

General features of ovarian metastasis include: bilaterality, multinodularity, involvement of the ovarian surface, extensive extraovarian spread, unusual patterns of dissemination, unusual histologic features, blood vessel and lymphatic invasion, and desmoplastic stromal reaction (Table 30.1).

Mode of Spread

The routes of tumor spread to the ovary are variable. Lymphatic and hematogenous metastasis to the ovaries is the most common form of dissemination.2–4 The importance of hematogenous spread is supported by the higher frequency of ovarian metastases in the well-vascularized ovaries of young patients. Embolic spread often produces multiple nodules within the substance of the ovary and commonly is accompanied by prominent intravascular nests of tumor cells in the ovarian hilum, meso-ovarium, and mesosalpinx.

Direct extension is also a common form of spread from adjacent tumors of the fallopian tube, uterus, and colorectum, for mesotheliomas, and for occasional retroperitoneal sarcomas.5 Transtubal spread provides an explanation for some surface ovarian implants from carcinomas of the uterine corpus,12 but may also account for some cases of spread from the uterine cervix.13,14 Neoplasms may also reach the ovary by the transperitoneal route from abdominal organs, such as the appendix.8 The metastatic tumor is found on the surface of the ovary or in the superficial cortex. Ovulation orifices may possibly represent a portal of entry for tumor cells.

Clinical Features

The circumstances leading to the discovery of the ovarian metastases depend on the site of the primary tumor.1,15 Ovarian metastases are detected before the breast cancer in only 1.5% of cases.15 In patients with a rectal or sigmoid colon cancer, the ovarian metastases and the primary tumor are discovered simultaneously, or more often, the intestinal tumor has been resected months or, years previously (50–75% of cases). Less frequently, the colorectal adenocarcinoma is discovered several months to years after resection of the ovarian metastases (3–20% of cases).3,16 In contrast, in about two-thirds of patients with Krukenberg tumor the diagnosis of the ovarian metastases precedes the discovery of the primary carcinoma.17,18 When a patient presents with abdominopelvic symptoms leading to suspicion of an ovarian tumor, the symptoms are nonspecific and similar to those of ovarian cancer, i.e., pelvic masses, ascites, or vaginal bleeding.17,19 Some patients with ovarian metastases have menstrual abnormalities, postmenopausal bleeding, and virilization, or they deliver a masculinized female fetus. These endocrine manifestations result from hormonally active luteinized stromal cells found in approximately one-third of metastatic tumors. Stromal luteinization occurs most frequently in association with metastatic mucinous carcinomas, particularly of colorectal or gastric origin.

Approximately 80% of patients with a Krukenberg tumor have bilateral ovarian metastases, and 73% of patients with ovarian metastases from breast carcinomas have extraovarian metastases.15,17 Radiologically, patients with a Krukenberg tumor more often have a solid mass with an intratumoral cyst, whereas primary ovarian cancers are predominantly cystic.20,21

Macroscopic Features

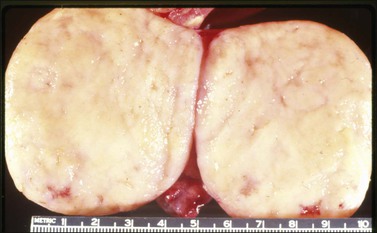

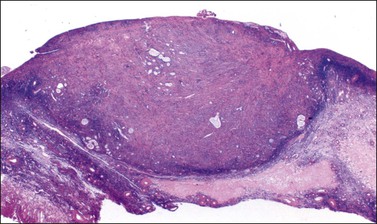

Ovarian metastases are bilateral in over 70% of cases (Figure 30.1).3 In contrast, the ovarian carcinomas most commonly mimicked by metastases (i.e., mucinous, endometrioid, and clear cell carcinomas) are bilateral in less than 15% of cases.22 Metastatic tumors grow as superficial or parenchymatous solid nodules or, frequently, as cysts. The size of ovarian metastases varies even from one side to the other. The ovaries may be only slightly enlarged or measure 10 cm or more. Intraoperative assessment of size and laterality may serve as a helpful guideline in distinguishing primary from metastatic mucinous tumors: bilateral tumors of any size or unilateral tumors under 10 cm have a high probability of being metastatic, whereas unilateral tumors over 10 cm are usually primary.23 However, there are many exceptions,24,25 especially in cases of colorectal and endocervical primaries.26 It is also noteworthy that metastases involving the ovary are often larger than their corresponding primary tumors.

Microscopic Features

The microscopic appearance of the metastases varies depending on the nature of the primary tumor.2–4 The identification of surface implants is extremely helpful in the recognition of secondary ovarian tumors that spread through the abdominal cavity and tubal lumen. Other features more commonly observed in metastatic tumors include multinodular infiltrative growth, single cell infiltration, follicle-like spaces (due to inadequate lymphatic drainage), and intravascular tumor emboli. Presence of a desmoplastic stroma and prominent stromal luteinization around tumor glands are also suspicious for metastasis.

Site of Origin

Intestinal Carcinomas

Most intestinal metastases originate in the large intestine and, much less frequently, in the small bowel. Whereas at autopsy metastases from intestinal carcinomas are less common than those from gastric carcinomas (14% vs 38%, respectively), at the time of operation metastases from intestinal carcinomas are almost five times as frequent as those from gastric carcinomas.27 Up to 45% of colorectal metastases to the ovary are clinically thought to be primary ovarian tumors, and many are misinterpreted as such on microscopic examination.2 Metastasis from the large bowel to the ovary is seen relatively more frequently when this cancer develops in women under 40 years of age. In one large series, one-fourth of patients were less than 40 years old28 and in another about 43% were under 50 years.29 In the latter study, it was found that patients initially presenting with an ovarian mass were significantly younger than those having ovarian spread in the setting of a known colorectal primary (average 48 vs 61 years). Not infrequently, patients have luteinized stromal cells in the ovarian tumor with resultant hormone production and endocrine symptoms.

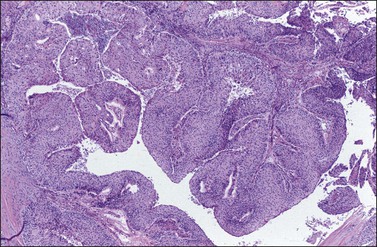

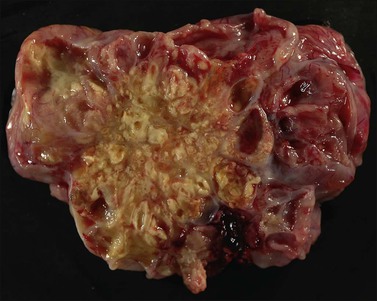

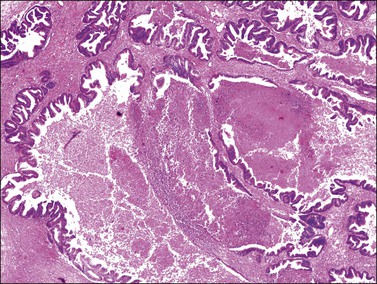

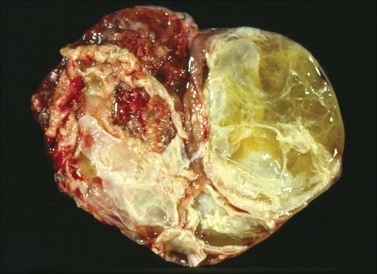

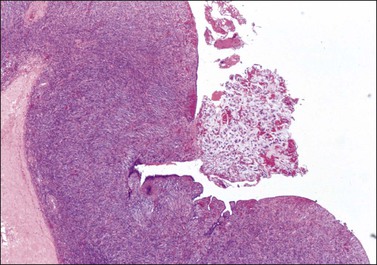

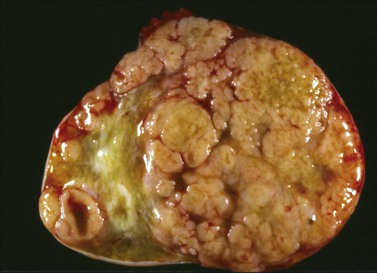

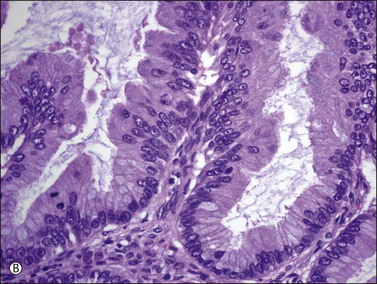

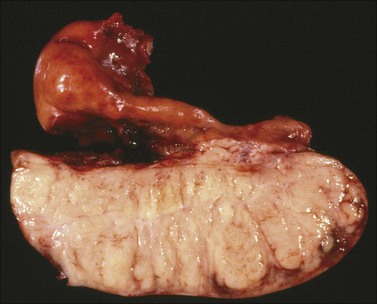

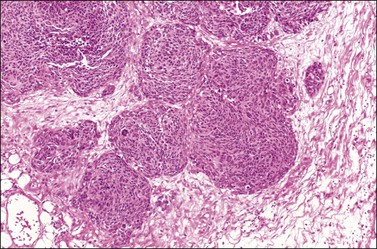

The ovarian tumors are bilateral in approximately two-thirds of cases (Figure 30.1). Smaller tumors are usually solid, whereas larger tumors are composed of friable gray, yellow, or red tissue with cysts that contain necrotic tumor, mucinous fluid, or blood (Figure 30.2).2,3

Figure 30.2 Metastatic carcinoma from the colon. Solid and cystic tumor with extensive necrosis and focal hemorrhage.

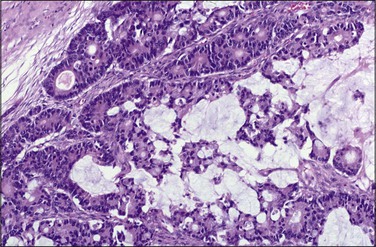

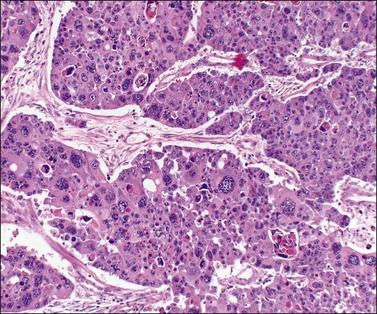

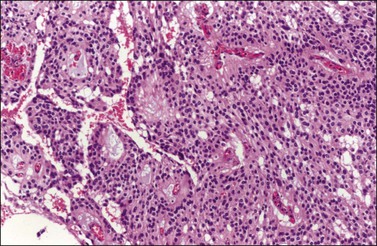

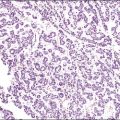

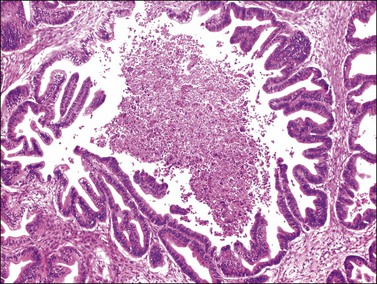

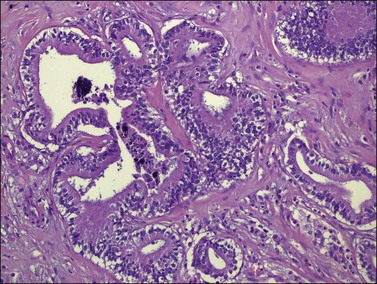

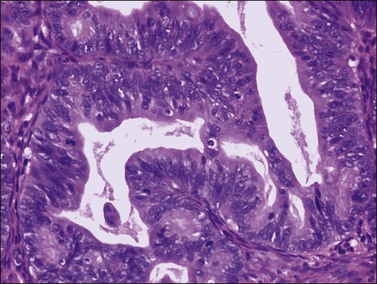

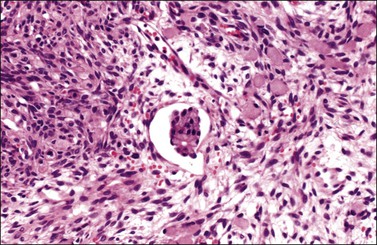

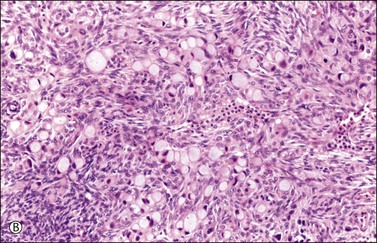

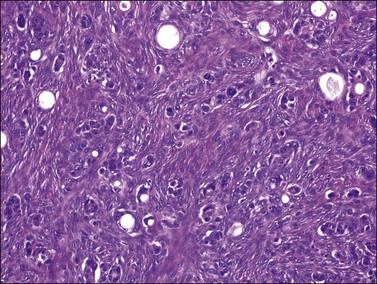

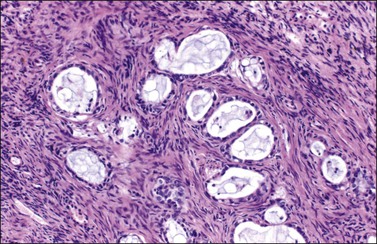

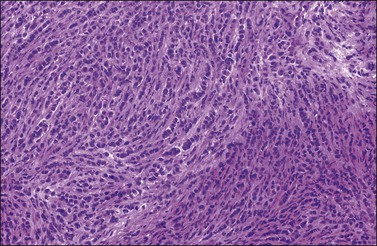

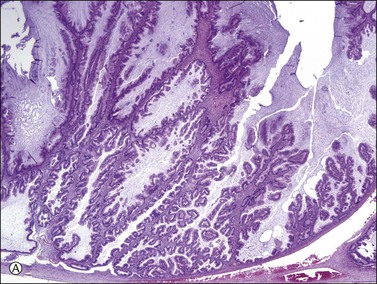

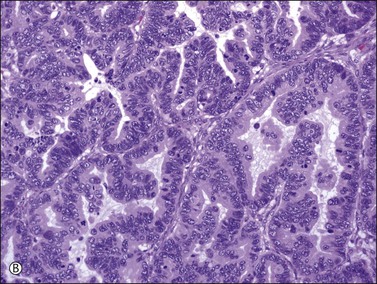

Microscopically, the metastatic tumors may be confused with primary endometrioid or mucinous carcinoma depending on whether the colonic carcinoma is predominantly non-mucinous or mucinous. Features that help distinguish colon cancer from endometrioid carcinoma include luminal necrotic debris (‘dirty necrosis’), focal segmental necrosis of the glands (Figures 30.3–30.5), occasional presence of goblet cells, and absence of müllerian features (squamous differentiation, an adenofibromatous component, or association with endometriosis). Also the nuclei lining the glands of metastatic colon carcinoma exhibit a higher degree of atypia than those of endometrioid carcinoma (Figure 30.5).2,3 The stroma may be desmoplastic (Figure 30.6), edematous, or myxoid, but frequently resembles ovarian stroma. Stromal luteinization is most frequently found in metastatic colorectal carcinomas.30

Figure 30.3 Metastatic adenocarcinoma from the colon. Garland-like glandular pattern with focal segmental necrosis of glands and abundant necrotic debris.

Figure 30.4 Metastatic adenocarcinoma from the colon. Focal segmental necrosis of glands and luminal necrotic debris (‘dirty necrosis’).

Figure 30.5 Metastatic adenocarcinoma from the colon. The glandular epithelium shows papillary growth and striking nuclear atypia (grade 3).

Figure 30.6 Metastatic adenocarcinoma from the colon. Neoplastic glands lying in a desmoplastic stroma.

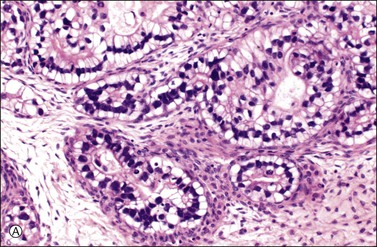

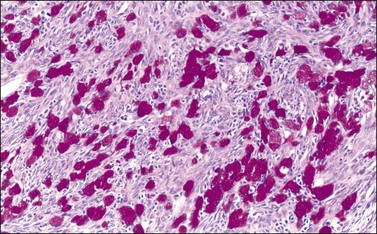

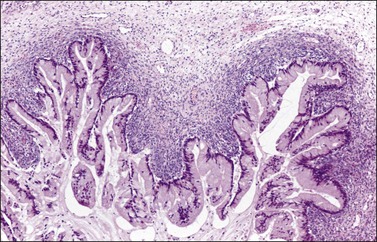

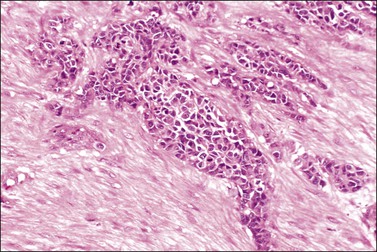

Metastatic tumors may also resemble closely primary mucinous ovarian tumors both grossly (Figure 30.7) and microscopically. The metastases may be moderately differentiated (Figure 30.8) or so well differentiated that they can be mistaken for mucinous borderline or less often benign ovarian tumors. Generous sampling (at least one block per 1–2 cm of tumor diameter) is recommended. Metastatic mucinous tumors to the ovary can originate in the large intestine, stomach, pancreas, gallbladder, biliary tract, appendix, and even, exceptionally, urachus and lung. Features supportive of the diagnosis of a metastasis already discussed include bilaterality, histologic surface involvement by epithelial cells (surface implants) (Figure 30.9), irregular infiltrative growth with desmoplasia (Figure 30.6), single cell invasion, signet-ring cells, vascular invasion (Figure 30.10), coexistence of benign-appearing mucinous areas with foci showing a high mitotic rate and nuclear hyperchromasia, and histologic surface mucin.31 In some cases, the intestinal metastases contain cells with abundant clear cytoplasm and may simulate either primary clear cell carcinoma or the secretory variant of endometrioid carcinoma (Figure 30.11).32

Figure 30.7 Metastatic carcinoma from the cecum. Multilocular mucinous cystic tumor with focal necrosis simulating an ovarian mucinous cystadenocarcinoma.

Figure 30.8 Metastatic adenocarcinoma from the colon. The mucinous glands are indistinguishable from those of a primary ovarian mucinous carcinoma. Mitotic figures are seen.

Figure 30.9 Metastatic adenocarcinoma from the colon. Ovarian surface involvement by mucinous epithelial cells (surface implant).

Figure 30.10 Krukenberg tumor. Vascular space invasion. Numerous signet-ring cells lie in the ovarian stroma.

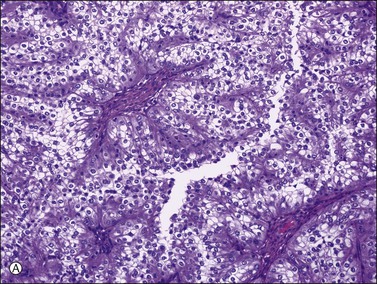

Figure 30.11 Metastatic adenocarcinoma from the small intestine. (A) Tubular glands lined by vacuolated cells resembling those of a secretory endometrioid carcinoma. Note the presence of stromal luteinization. (B) Typical Krukenberg tumor component encountered after additional sampling. Numerous signet-ring cells with eccentric nuclei and pale vacuolated cytoplasm are seen.

Immunohistochemistry

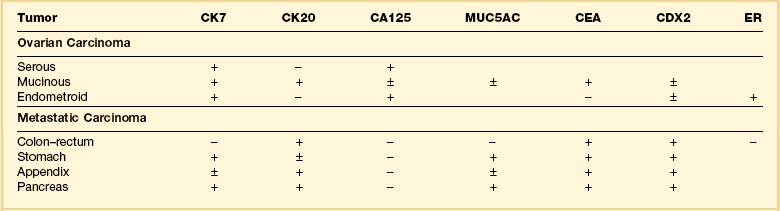

Immunohistochemical stains can be helpful in distinguishing primary adenocarcinoma of the ovary from metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma (Table 30.2). Cytokeratin (CK) immunostains are the most commonly used. Primary ovarian carcinomas are almost always immunoreactive for CK7 whereas colorectal adenocarcinomas are usually CK7 negative.33,34 Mucinous adenocarcinomas of the ovary may be immunoreactive for CK20, but the reaction is typically weak and focal.33,35 Endometrioid adenocarcinomas are almost invariably CK20 negative.34 In contrast, colorectal adenocarcinomas are diffusely and strongly reactive for CK20. Therefore, a CK7-positive/CK20-negative immunoprofile favors a primary ovarian carcinoma, whereas a CK7-negative/CK20-positive immunoprofile suggests metastatic adenocarcinoma (Table 30.2).35–37 Although the vast majority of colorectal adenocarcinomas express CK20, poorly differentiated and right-sided tumors can be CK20 negative.38 Furthermore, adenocarcinomas of the appendix, small intestine, and stomach can be CK7 positive. Thus, immunostains for CK7 and CK20 should be interpreted with caution, always in the light of all clinical information, and with the understanding that no tumor shows absolute consistency in its staining with these markers.

Table 30.2

Primary Ovarian Carcinomas versus Metastatic Gastrointestinal Carcinomas (Immunophenotypes)

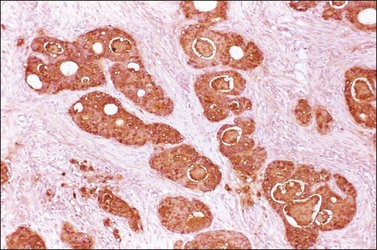

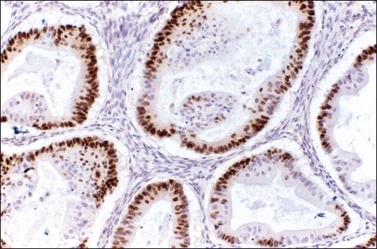

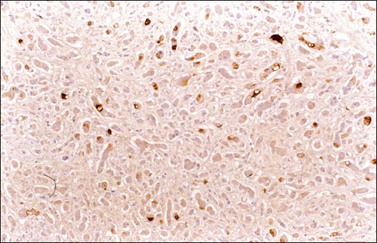

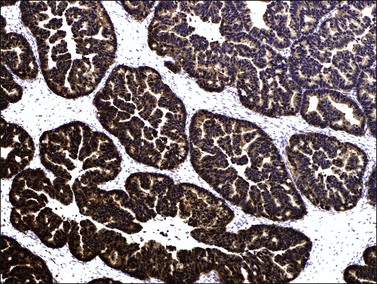

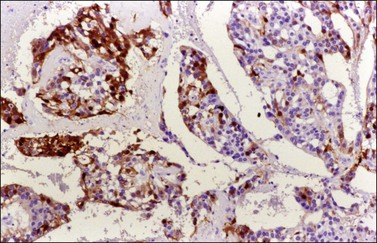

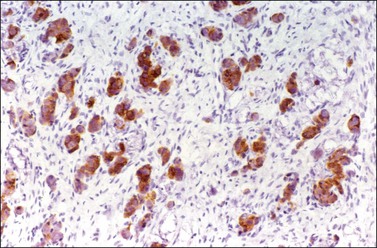

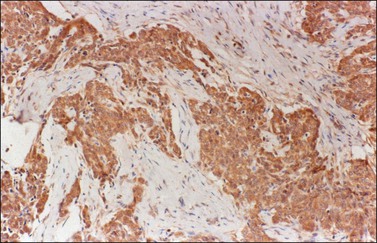

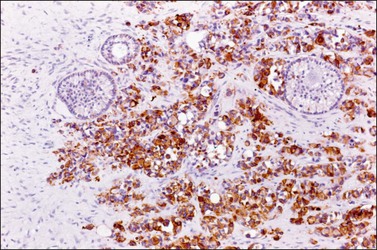

Other immunohistochemical stains have greater overlap in their expressions and should not be used individually in this differential diagnosis. Nevertheless, after taking into account the clinicopathologic findings and the results of the CK immunostains, negative stainings for vimentin39 CA125 and gastric mucin gene MUC5AC,35 and strongly positive staining for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) (Figure 30.12)33,34 favor metastatic colorectal cancer over primary ovarian adenocarcinoma (Table 30.2). Likewise, strong immunoreactivity for P53 (Figure 30.13) supports the colonic origin of the neoplasm. CDX2 is often strongly and diffusely positive in colorectal carcinomas, but it can also be positive in ovarian mucinous and endometrioid tumors.40,41 Estrogen receptors (ERs) may be helpful for distinguishing endometrioid adenocarcinomas from metastatic intestinal carcinomas, as the former are usually positive and the latter are negative.42

Krukenberg Tumor

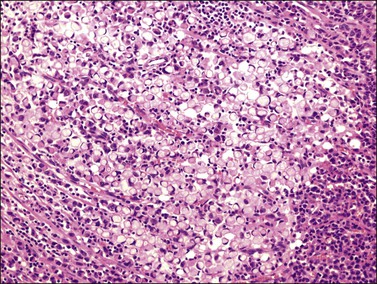

Krukenberg tumors are adenocarcinomas with a distinctive histologic appearance. They consist of mucin-filled signet-ring cells and a striking proliferation of the ovarian stroma. Signet-ring cell carcinomas are associated more often with ovarian metastasis than carcinomas of other histologic types. These tumors originate in the stomach, usually in the pylorus, in the vast majority of cases. It has been demonstrated that gastric signet-ring cell carcinomas metastasize to the ovary much more often than intestinal-type carcinomas of the stomach do.43 Sometimes, the gastric cancer may be small and remains undetected for several years after oophorectomy. Much less frequently, the primary tumor is in the large intestine, breast, gallbladder, uterine cervix, appendix, or urinary bladder. In rare cases, the site of origin of the primary tumor is unknown and a diagnosis of ‘primary’ Krukenberg tumor has been proposed for those cases in which either the patient survives in good health for 10 years or longer or a thorough autopsy fails to reveal an extraovarian primary tumor.44 Possibly, some of the cases reported in the older literature as primary Krukenberg tumors represent mucinous (goblet cell) carcinoids. Patients with Krukenberg tumors tend to be younger than most patients with metastatic carcinoma; most of them are between 40 and 50 years of age. Although the symptoms are usually nonspecific, most frequently abdominal pain and swelling, endocrine manifestations, such as virilization during pregnancy, may result from stromal luteinization.3

Krukenberg tumors are bilateral in 60–80% of the cases.3 They are typically solid masses with smooth nodular or bosselated outer surfaces (Figure 30.14). The cut surfaces are predominantly white or tan with areas of red or brown discoloration (Figure 30.15); the consistency may be firm, fleshy, or gelatinous. Because of the marked proliferation of the ovarian stroma, the tumors may resemble fibrothecomas on gross examination.

Figure 30.15 Krukenberg tumor. The cut surface shows solid beige-yellow tissue with small foci of hemorrhage.

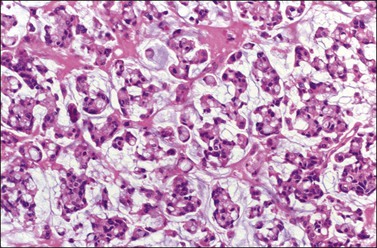

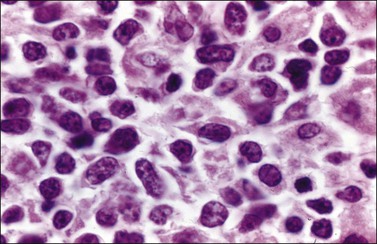

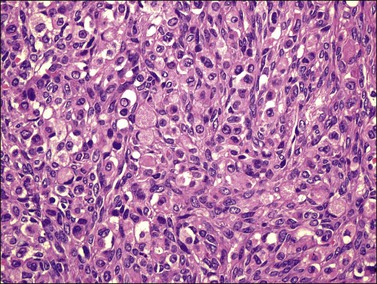

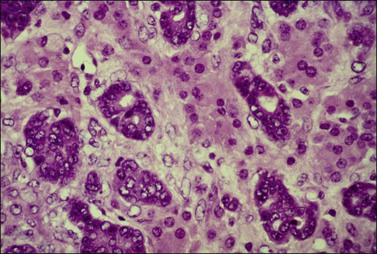

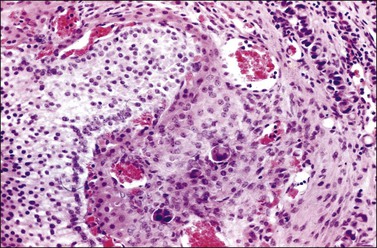

Microscopically, the plump, rounded carcinoma cells have a signet-ring appearance and are surrounded by a dense cellular stroma (Figure 30.16). The epithelial cells may appear singly or in nests (Figure 30.17) and tend to concentrate in the dense fibroblastic areas. In some cases, the stroma is less cellular, edematous (Figure 30.18), or fibrous. Isolated small glands are usually found45 (Figure 30.19) and, occasionally, there is a predominant tubular architecture (tubular Krukenberg tumor) (Figure 30.20).6 The stromal cells are plump, spindle shaped, and are sometimes extensively luteinized.3,6

Figure 30.16 Krukenberg tumor. Numerous signet-ring cells with pale cytoplasm are arranged irregularly within a cellular stroma.

Figure 30.17 Krukenberg tumor. The signet-ring cells have eosinophilic cytoplasm and are distributed singly or in nests.

Figure 30.19 Krukenberg tumor. Small glands lined by moderately atypical epithelial cells are admixed with signet-ring cells.

Figure 30.20 Tubular Krukenberg tumor. The tubular glands are lined by markedly atypical cells. The intervening clusters of luteinized stromal cells contribute to the resemblance to a Sertoli–Leydig cell tumor.

Krukenberg tumors must be distinguished from primary and other metastatic ovarian tumors including clear cell adenocarcinoma, mucinous (goblet cell) carcinoid, and a variety of ovarian tumors that contain signet-ring-like cells filled with non-mucinous material. The presence of clear cells may raise the issue of clear cell carcinoma, but the clear cells in the latter contain glycogen; mucin, when present, is typically luminal and extracellular. Rarely, clear cell carcinoma may have a signet-ring cell component that simulates a Krukenberg tumor; however, the signet-ring cells of the former have a characteristic ‘targetoid’ cytoplasm (bull’s eye appearance), containing a large vacuole with a central eosinophilic body. In addition, the identification of a tubulocystic pattern, as well as the presence of hobnail cells, stromal hyalinization, and eosinophilic secretion, is helpful in establishing the diagnosis. In contrast, CK immunostains are not useful, as nearly half of gastric carcinomas metastatic to the ovary are CK7 positive/CK20 negative.38 Mucinous carcinoid, either primary or metastatic, may contain large areas of signet-ring cells; the former neoplasms, however, frequently contain other teratomatous elements, and Grimelius stains as well as immunostains for chromogranin, synaptophysin are usually positive in both.

The tubular variant of Krukenberg tumor, sometimes associated with stromal luteinization, can be confused with a Sertoli–Leydig cell tumor (Figure 30.20); however, signet-ring cells are not a feature of the latter tumor except for the heterologous form that contains mucinous intestinal glands.6 Positive mucicarmine and periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stains with diastase digestion (Figure 30.21) are of great value in establishing the diagnosis of a Krukenberg tumor.6 Occasional Krukenberg tumors may closely resemble fibromas on macroscopic examination and may have relatively few signet-ring cells. Bilaterality and positive mucin stains facilitate the differential diagnosis.

Figure 30.21 Krukenberg tumor. A PAS–diastase stain demonstrates the mucin in the vacuolated tumor cells.

Almost all patients die within a year of the diagnosis of Krukenberg tumor, but rare patients have survived for 5 or more years after gastrectomy and bilateral oophorectomy.46 Although exceptional, this outcome justifies removal of both the stomach and the ovarian metastases in cases in which the tumor appears limited to those organs. Also, in menopausal and postmenopausal women undergoing gastrectomy for carcinoma, the ovaries should be removed routinely to prevent the later development of ovarian metastasis and avoid another operation.

Carcinoid Tumors

Carcinoid tumors of the gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, or bronchus may metastasize to the ovary, and approximately half of the patients have the carcinoid syndrome.47 The primary tumor is usually in the ileum. Whereas mucinous carcinoid tumors of the appendix spread to the ovary in approximately one-third of cases, typical carcinoid tumors of the appendix almost never metastasize to the ovary.3 In the largest series reported, the age of the 35 patients ranged from 21 to 82 years, with a median of 57 years.47 Forty percent of the women had preoperative manifestations of the carcinoid syndrome. Some of them also had clinical evidence of intestinal or ovarian involvement. Extraovarian metastases were found in at least 90% of the cases, in contrast to the rarity of similar spread in cases of primary ovarian carcinoids.

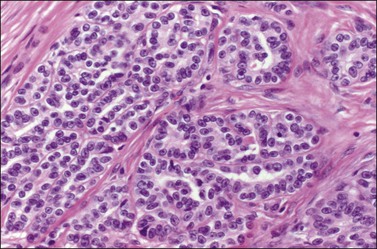

Metastatic carcinoids are typically bilateral solid tumors with smooth or bosselated surfaces. The cut section often shows firm white or yellow confluent nodules, which may simulate fibromas or thecomas (Figure 30.22). Rare carcinoid tumors are predominantly cystic.3 Microscopically, the insular pattern is the most common, but trabecular and mucinous patterns may also be found. The carcinoid glands usually appear scattered in a dense fibrous stroma, which may be hyalinized (Figures 30.23 and 30.24). Focally, metastatic mucinous (goblet cell) carcinoids may resemble Krukenberg tumors. Immunostains for chromogranin and synaptophysin are often positive (Figure 30.25).

Figure 30.22 Metastatic carcinoid tumor from the pancreas. The sectioned surfaces are solid and white-yellow simulating those of a fibroma or thecoma.

Figure 30.23 Metastatic mucinous carcinoid tumor from the appendix. The ovary is partly replaced by a nodule of dense fibrous tissue containing scattered small glands.

Figure 30.24 Metastatic mucinous carcinoid tumor from the appendix. Small glands lined by flat to cuboidal mucinous epithelium and occasional goblet cells. The intervening stroma appears fibromatous.

Figure 30.25 Metastatic mucinous carcinoid tumor from the appendix. Positive chromogranin immunoreaction.

Metastatic carcinoids can be confused with primary carcinoids (Table 30.3), granulosa cell tumors, Sertoli–Leydig cell tumors, Brenner tumors, adenofibromas, or endometrioid carcinomas.3,5 If the diagnosis of a carcinoid tumor is difficult in any of the previous situations, more thorough sampling, and immunohistochemical staining for neuroendocrine markers can be performed. Bilaterality, extraovarian extension, and absence of teratomatous elements are important features of metastatic carcinoids. CDX-2 does not distinguish between tumors of intestinal origin and primary ovarian carcinoids.48

Table 30.3

Primary versus Secondary Carcinoid Tumor: Differential Diagnosis

| Metastatic Carcinoid | Primary Carcinoid |

| Clinical Profile | |

| Primary site apparent in 80% | No intestinal tumor |

| Peritoneal seeding and abdominal metastases frequent | Extraovarian spread uncommon |

| Early recurrence and progression | Low rate of recurrence |

| Macroscopic Features | |

| Bilateral almost always | Unilateral always |

| Cut surface nodular and variegated | Cut surface homogeneous |

| Microscopic Features | |

| Teratomatous elements absent | Teratomatous elements usually present |

Breast Carcinoma

Ovarian involvement by breast cancer is usually an incidental microscopic finding without clinical significance (Figure 30.26). Historically, such tumors have been found in approximately 30% of patients who have had therapeutic oophorectomy for disseminated breast carcinoma and, at autopsy, in about 10% of cases of breast cancer. Bilateral involvement occurs in 60–80% of cases.3

Figure 30.26 Metastatic carcinoma from the breast. Several nests of carcinoma cells are seen in the highly vascular theca layer of a Graafian follicle.

Patients with breast cancer are at increased risk of developing primary ovarian, tubal, or pelvic peritoneal carcinoma, especially if they have a hereditary predisposition to breast and ovarian cancer due to BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. It is not surprising then that patients with a history of breast cancer who present with an adnexal or pelvic mass are more likely to have independent ovarian or tubal malignancy than metastases from the breast cancer by a 3 : 1 ratio.49 The very rare cases of metastases that present clinically as primary ovarian tumors before the detection of the breast carcinoma often pose diagnostic difficulty.50 The tumors are characteristically solid, multinodular, and firm (Figure 30.27). A larger percentage of cases of lobular carcinoma of the breast, including those of signet-ring cell type, metastasize to the ovary than do cases of ductal carcinoma; in an autopsy study 36% of the former metastasized to the ovaries in contrast to only 2.6% of the latter.51

Figure 30.27 Metastatic carcinoma from the breast. The sectioned surface appears solid and multinodular.

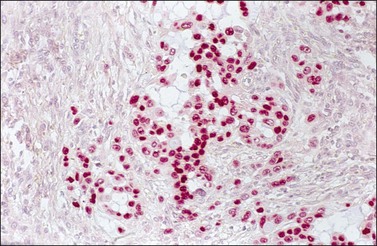

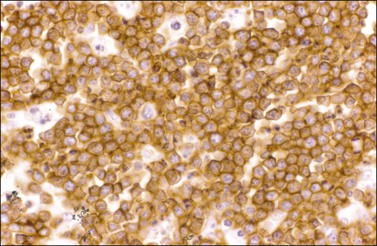

Metastatic lobular carcinomas (Figure 30.28) usually show a diffuse pattern mimicking granulosa cell tumors, granulocytic sarcomas, or lymphomas, or even an insular pattern simulating carcinoid tumors. Rarely, metastatic ductal carcinomas may have an endometrioid-like appearance. Positive immunoreaction for gross cystic disease fluid protein (GCDFP-15) (Figure 30.29),52 estrogen (ERPr) (Figure 30.30), and progesterone receptor proteins (ER, PR), epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), and S-100 protein, and negativity for CA12.5, CA19.9,53 α-inhibin, myeloperoxidase, and lymphoid markers favor metastatic breast carcinoma. Mammaglobin is expressed in about 50% of breast carcinomas.54,55 However, its expression has been demonstrated in rare ovarian serous carcinomas and in endometrioid carcinomas of the uterine corpus.54,56 WT1 is positive in >80% of serous carcinomas of the ovary, but it is rarely positive in breast carcinomas. PAX-8 immunoreaction is seen in greater than 88% of ovarian carcinomas but not in breast carcinomas.57 Both breast and ovarian carcinomas may be positive for CK7.36 A panel of markers is recommended as no currently available individual marker is entirely specific for breast or ovarian carcinomas.

Figure 30.28 Metastatic carcinoma from the breast, lobular type. The tumor cells show a single-file arrangement.

Tumors of the Pancreas, Biliary Tract, and Liver

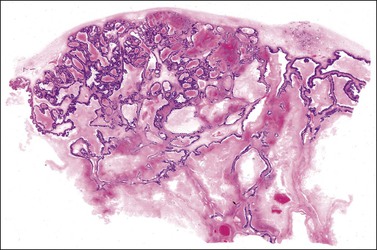

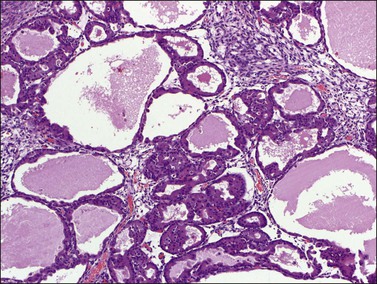

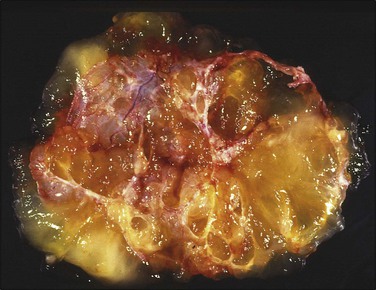

Although ovarian metastases are rarely found in patients with these carcinomas, they may strikingly mimic primary ovarian tumors both grossly and microscopically.58–60 Metastatic tumors from the pancreas are usually bilateral, large, cystic, and multiloculated (Figure 30.31), an appearance that may be indistinguishable from primary mucinous neoplasia, although in some cases surface nodules may be noted and raise suspicion for metastasis. The microscopic pattern varies considerably within individual tumors that may show areas resembling ovarian mucinous cystadenomas, borderline tumors (Figure 30.32), and well-differentiated cystadenocarcinomas as well as foci of irregular stromal infiltration.58 In some cases, foci of high-grade adenocarcinoma appear admixed with more indolent low-grade cystic tumor and are a clue to the diagnosis. Four cases of ovarian involvement by acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas have been recently reported61 (Figure 30.33). Metastatic adenocarcinomas of the gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts are very rare.59 Recently, however, a series of cases has been reported.62 They are usually solid tumors that microscopically may simulate ovarian mucinous (Figure 30.34) or endometrioid carcinomas, or even cystadenofibromas.59 Rarely, Krukenberg tumors originate in the pancreas or biliary tract.3 Features suggesting metastasis include bilaterality, extraovarian extension, ovarian surface implants, and vascular invasion. Like primary ovarian mucinous tumors, pancreatic carcinomas are diffusely immunoreactive for CK7 and MUC5AC and show focal to diffuse positivity for CK20 (Table 30.2); however, 46% of pancreatic carcinomas are negative for Dpc4.35

Figure 30.31 Metastatic carcinoma from the pancreas. Multiloculated cystic tumor simulating a primary mucinous tumor.

Figure 30.32 Metastatic carcinoma from the pancreas. The lining epithelium resembles that of a mucinous intestinal borderline tumor. Note the condensation of the ovarian stroma adjacent to the tumor.

Figure 30.33 Metastatic acinar cell carcinoma from the pancreas. High-power view of typical small acini and cystic glands.

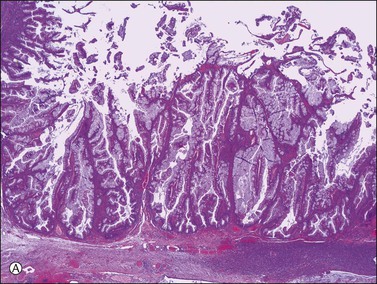

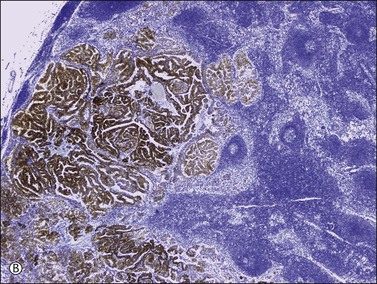

Figure 30.34 Metastatic intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. (A) Proliferation of mucinous epithelium with filiform branching papillae simulating an ovarian mucinous borderline tumor. (B) The mucinous intestinal epithelium shows stratified cells with moderate nuclear atypia.

Ovarian metastases from hepatocellular carcinomas are exceedingly rare and should be distinguished microscopically from primary hepatoid carcinomas (Chapter 27), and hepatoid yolk sac tumors (Chapter 29). HepPAR1 is not useful in distinguishing among metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma, hepatoid yolk sac tumor, and hepatoid ovarian carcinoma as it is expressed in all.63 The presence of bile in the ovarian tumor favors metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma.60

Tumors of the Appendix

Metastatic tumors from the appendix are rare and represent only 1–2% of ovarian metastases.1 Most of these cases are mucinous tumors of borderline malignancy (low-grade mucinous tumors) associated with pseudomyxoma peritonei8,64,65 (see Chapters 26 and 31). Other appendiceal tumors that may spread to the ovary include mucinous (goblet cell) carcinoids3,66 and, less frequently, adenocarcinomas of signet-ring cell (Figure 30.35), mucinous intestinal, and colorectal types (Figure 30.36).10 The ovarian metastases of mucinous carcinoids and signet-ring cell adenocarcinomas are generally of the Krukenberg type. The former tumors are clinically aggressive and often fail to show the characteristic immunoreactions of carcinoid tumors. A recent report on ovarian metastases of appendiceal carcinomas with neuroendocrine differentiation emphasized that the clinical features and pathologic findings support classifying the appendiceal tumors as carcinomas rather than goblet cell carcinoids. According to the authors, the presence of infiltrative and destructive growth justifies their designation as carcinomas.67

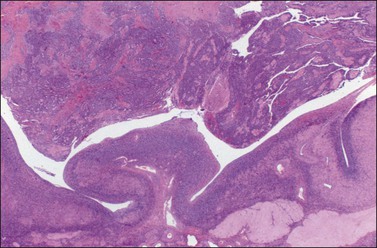

In patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei, low-grade mucinous tumors of the appendix often coexist with histologically similar tumors in one or both ovaries. Although these tumors were traditionally considered as independent primary neoplasms, there is now convincing clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic evidence that in most cases the ovarian tumors represent metastases from the appendiceal lesions.8,9,64,65,68 In such cases, the ovarian tumors are frequently bilateral or, when unilateral, predominantly right-sided, and often exhibit pools of mucin dissecting through the ovarian stroma (‘pseudomyxoma ovarii’). In contrast, primary ovarian mucinous borderline tumors are usually unilateral and only occasionally associated with pseudomyxoma peritonei or ovarii, even when preoperative or surgical rupture has occurred. Additional features that support the secondary nature of the ovarian tumors associated with pseudomyxoma peritonei are their jelly-like consistency on gross examination (Figure 30.37), the finding of mucin and atypical mucinous cells on the ovarian surfaces, and the presence of very tall mucinous lining cells (Figure 30.38).3 Although appendiceal tumors are almost always diffusely positive for CK20, they may also be positive for CK7 in approximately one-third of cases.35

Figure 30.37 Metastatic low-grade mucinous tumor from the appendix. Multiloculated cystic tumor with abundant mucoid material.

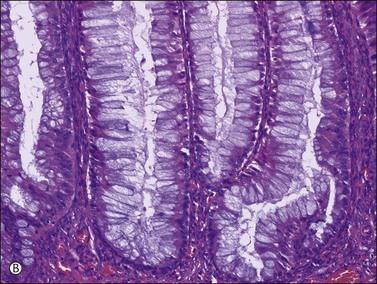

Figure 30.38 Metastatic low-grade mucinous tumor from the appendix. (A) The mucinous cells are tall and lack nuclear atypia. (B) Mucin appears to be discharged from the apical pole of the columnar cells.

At surgery, the primary appendiceal tumor is often overlooked because the ovarian tumors are usually much larger.10 Besides, the site of appendiceal rupture may be very small and require extensive sectioning to demonstrate it. Additionally, in some cases a rupture site heals over, and is represented only by fibrosis in the appendiceal wall.

Renal Tumors

Renal cell carcinoma rarely metastasizes to the ovaries; however, when it does, it must be distinguished from a primary clear cell carcinoma. Only 15 cases have been reported in detail.69–72 Most were unilateral tumors, often large (average 12.5 cm in greatest dimension), solid and cystic, and yellow to orange. Microscopically, they showed a prominent sinusoidal vascular pattern, a homogeneous clear cell pattern without hobnail cells, absence of hyalinized papillae, and the absence of intraluminal mucin (Figure 30.39).3,72

Figure 30.39 Metastatic papillary renal cell carcinoma. (A) The renal clear cell carcinoma lacks hobnail cells, hyalinized papillae, and intraluminal mucin. (B) Lymph node metastasis showing a strong racemase immunoreaction.

A panel of antibodies may be helpful in the differential diagnosis: ovarian clear cell carcinomas are usually immuno- reactive for CK7 and mesothelin and negative for CD10 and RCCma (renal cell carcinoma marker), whereas renal cell carcinomas often show the opposite immunoprofile (CK7−/mesothelin−/CD10+/RCCma+).73–75 Although PAX2 may be a more sensitive marker than RCCma for metastatic renal cell carcinoma, it should be noted that about 40% of ovarian clear cell carcinomas also express PAX2.76

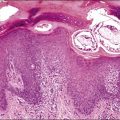

Tumors of the Urinary Tract

Distinction between a transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary tract metastatic to the ovary (Figure 30.40) and a borderline or malignant Brenner tumor, or a primary ovarian transitional cell carcinoma, may be difficult.77,78 Clinical information may be necessary to resolve the issue. In most borderline or malignant Brenner tumors, however, a benign Brenner tumor component can be found. Also, the presence of benign mucinous elements favors the diagnosis of a Brenner tumor. In contrast to primary transitional cell carcinomas of the ovary, urinary tract carcinomas are immunoreactive for CK13, CK20, uroplakin, and thrombomodulin79 and they are typically negative for WT1.80

Adrenal Gland Tumors

Neuroblastoma is the adrenal tumor that most frequently metastasizes to the ovary.81–83 The metastases must be distinguished from rare cases of primary ovarian neuroblastomas. In contrast to the metastatic tumors, the primary tumors are usually unilateral and are often associated with a teratoma. The prominent fibrillary background of neuroblastoma and the presence of pseudorosettes help in the distinction of metastatic neuroblastoma from other metastatic small cell tumors. Immunohistochemistry is also helpful. Metastases of adrenal cortical carcinomas to the ovary are exceedingly rare.84 Pheochromocytomas spread to the ovary even less commonly.

Malignant Melanoma

Three series of melanomas metastatic to the ovary including 52 cases have been reported.85–87 In the ovary metastatic malignant melanoma may be confused with primary malignant melanoma; the latter is unilateral, usually associated with a dermoid cyst, and often nonpigmented. When a melanoma is composed predominantly of large cells, it may resemble a lipid-poor steroid cell tumor or a pregnancy luteoma; sometimes, it exhibits a follicle-like arrangement resembling juvenile granulosa cell tumor; when it is composed mainly of small cells it may be confused with a small cell carcinoma of the hypercalcemic type.87 Positive stains for melanin, S-100 protein (Figure 30.41), Melan A, and/or HMB-45 should establish the diagnosis of melanoma.

Pulmonary and Mediastinal Tumors

Ovarian metastases from lung carcinomas account for less than 1% of ovarian metastases but are increasing in frequency as the disease becomes more common in women88 (Figure 30.42). Most women present with symptoms of the pulmonary tumor and are subsequently found to have a pelvic tumor. All major histologic types of lung cancer can spread to the ovaries and potentially mimic a primary carcinoma. Squamous cell carcinomas, the most common form of lung cancer, rarely metastasize to ovaries.88 Metastases from lung adenocarcinomas are slightly more frequent. Thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) immunoreactivity helps identify lungs as a potential primary site in cases of metastatic adenocarcinoma of unknown origin; it is reactive in 60–75% of primary lung adenocarcinomas, but not reactive in primary ovarian adenocarcinomas.89 Undifferentiated small cell (oat cell) carcinomas of the lung, the most common type of pulmonary metastasis, should be distinguished from ovarian small cell carcinomas of either ‘hypercalcemic type’ or ‘pulmonary type’ (see Chapter 27), although all of the tumors have a poor prognosis. Ovarian small cell carcinomas of hypercalcemic type occur in young women and, like other ovarian tumors, are negative for TTF-1, while more than half of small cell lung carcinomas are reactive.88,90 Primary ovarian small cell carcinoma of pulmonary type typically differs from metastatic small cell lung carcinoma in its tendency for peritoneal spread and its association with epithelial–stromal tumors, in particular endometrioid carcinoma. Interestingly, however, small cell carcinoma of the lung has been reported to metastasize to pre-existing ovarian tumors.88,91

Metastatic large cell carcinomas must be distinguished from morphologically similar oxyphilic tumors, both primary and secondary, including melanoma. Bronchioloalveolar carcinomas rarely are metastatic to the ovaries.92

Small cell carcinomas arising in sites other than lung, such as mediastinum, uterine cervix, and gastrointestinal tract, may also metastasize to the ovaries.93,94 Isolated cases with metastases include posterior mediastinal neuroblastoma82 and mediastinal thymoma.95

Uterine Tumors

Ovarian involvement by endometrial carcinoma has been reported in 5–15% of hysterectomy specimens. The distinction between metastatic endometrial and primary endometrioid carcinoma of the ovary has been discussed in Chapter 27. Uterine sarcomas may metastasize to the ovary and may occasionally be discovered before the primary tumor.96 Metastatic epithelioid leiomyosarcoma may have an appearance that simulates a carcinoma, a malignant lymphoma, or even a Sertoli cell tumor. A positive immunoreaction for desmin may facilitate the diagnosis. Distinction between metastatic low-grade endometrial–stromal sarcoma, primary ovarian low-grade endometrioid stromal sarcoma, and sex cord–stromal tumors has been discussed in Chapter 27.

Mucinous adenocarcinomas of the cervix coexist with ovarian tumors of similar type more frequently than other adenocarcinomas.97–99 Sometimes, it may be difficult to determine whether the tumors are metastatic from one organ to the other or independent primary neoplasms. The distinction is made by applying criteria similar to those used in diagnosing simultaneous ovarian and corpus carcinomas and in identifying metastatic tumors in general. However, the microscopic clue to the metastatic nature of the ovarian tumors is the ‘hybrid’ appearance of the epithelium with features of both endometrioid and mucinous differentiation, i.e., with low-power endometrioid-like features but with apical mucin seen on higher power. Additionally, the nuclei are hyperchromatic and more atypical than seen in true endometrioid or mucinous carcinomas with a similar glandular grade, and mitotic figures and apoptotic bodies are numerous (Figure 30.43).100,101 Although nonspecific, a strong p16 immunoreaction (Figure 30.44) supports the metastatic nature of the ovarian tumor, which can be confirmed by detecting human papillomavirus (HPV) using in situ hybridization or polymerase chain reaction. In some cases, an occult primary cervical adenocarcinoma was discovered after resection of the ovarian metastases.100 Subsequently, the question of whether ovarian conservation is justified in patients with cervical adenocarcinoma has been raised.

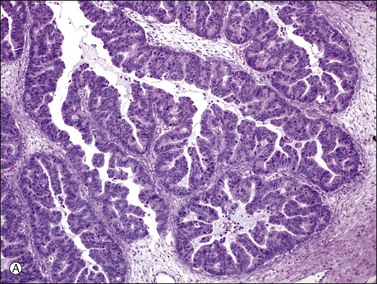

Figure 30.43 Metastatic endocervical adenocarcinoma of the usual type. (A) Papillary tumor resembling endometrioid carcinoma at low magnification. (B) Apical mucin is seen on higher power. Mitotic figures and apoptotic cells are numerous.

Cervical squamous cell carcinomas metastasize to the ovary in less than 1% of cases.102,103 Most ovarian squamous cell carcinomas arise in dermoid cysts or endometriotic cysts. Adenosquamous, neuroendocrine, undifferentiated, and transitional cell carcinomas metastatic to the ovary have also been reported.102

Uterine choriocarcinomas spread to the ovary in 22% of cases.5 It may be extremely difficult to distinguish a primary ovarian choriocarcinoma of either gestational or germ cell origin from a metastatic uterine choriocarcinoma in which regression of the primary tumor has occurred. The specimen should be thoroughly sampled in an attempt to discover teratomatous elements, thus establishing a germ cell origin of the neoplasm.

Carcinomas of the fallopian tube involve the ovary in approximately 13% of cases, usually by direct extension.1 In such cases, it may be difficult to determine whether the tumor is primary in the tube or ovary. Although the problem is usually resolved on the basis of the gross pathologic findings, in questionable cases the tumor is classified as tubo-ovarian carcinoma.51 Most tubal carcinomas resemble high-grade serous carcinomas of the ovary, thus microscopic examination rarely helps in deciding a primary site.104,105 Recent studies have raised the possibility that a great number of high-grade serous carcinomas of the ovary, predominantly from BRCA-positive patients but also sporadic cases, may actually represent spread of fallopian tube cancers, especially those of the fimbria106–109 (see Chapter 25).

Lymphoma and Leukemia

Although lymphoma and leukemia can involve the ovaries simulating various primary tumors, they rarely present clinically as an ovarian mass. In countries where Burkitt lymphoma is endemic, however, it accounts for approximately half the cases of malignant ovarian tumors in childhood.3 On pelvic examination, unilateral or bilateral adnexal masses are palpable. Approximately two-thirds of the patients have extraovarian disease frequently involving the fallopian tubes, and the pelvic or para-aortic lymph nodes. The Ann Arbor lymphoma stage provides more prognostic information than the International Federation of Gynecologists and Obstetricians stage. With modern combination chemotherapy, patient survival is greater than 50% and is comparable to that achieved overall in nodal lymphomas.110

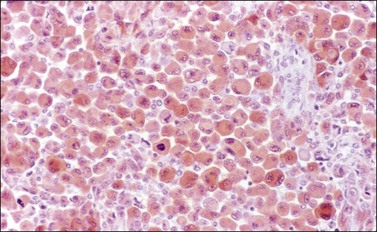

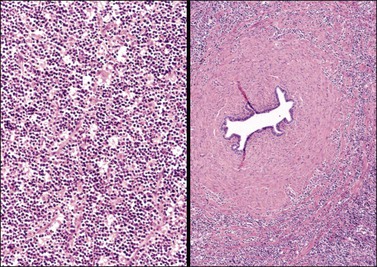

Ovarian lymphomas have an average diameter of 10–15 cm.3 The external surface of the tumor is smooth, nodular, or bosselated. The cut surface is fleshy and tan, or gray (Figure 30.45). Microscopically, the tumor cells of Burkitt and Burkitt-like lymphomas grow in sheets punctuated by spaces that contain phagocytic histiocytes, creating a characteristic ‘starry sky’ appearance (Figure 30.46). The cells have scanty cytoplasm and uniform, round, medium size nuclei with coarse chromatin and 1–3 nucleoli. Mitotic figures are numerous. The tumor cells can infiltrate ovarian follicles without destroying them. In adults, large cell lymphoma is the most common type. The tumor cells show scanty to moderate amphophilic cytoplasm and round, oval, or cleaved nuclei (Figure 30.47). The nuclei are hyperchromatic with coarse chromatin or vesicular with a prominent central nucleolus. Mitotic figures are frequent. Other types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, both follicular and diffuse, rarely involve the ovary.

Figure 30.45 Burkitt-like lymphoma. The sectioned surface is lobulated and fleshy resembling that of a dysgerminoma. Notice the marked enlargement of the fallopian tube which is infiltrated by lymphoma.

Figure 30.46 Burkitt-like lymphoma. Left: A ‘starry-sky’ pattern is apparent. Right: The tumor cells infiltrate the wall of the fallopian tube.

Dysgerminoma is one of the most common and difficult differential diagnoses. The appearance of the cell nuclei is very important. Immunostains for lymphoid markers, such as CD45 (leukocyte common antigen), CD20 for B-cells (Figure 30.48), and CD3 for T-cells, and placental alkaline phosphatase, c-kit, and D2-40 for dysgerminoma are helpful. Dysgerminomas also react for pluripotency markers (transcription factors) SALL4 and OCT3/4. Most ovarian lymphomas have a B-cell phenotype.111 The ‘single-file’ arrangement of lymphoma and leukemic cells may simulate metastatic lobular carcinoma of the breast; however, the cells of the latter tumors often contain small mucin-filled intracytoplasmic vacuoles and are immunoreactive for CKs. Carcinoid, granulosa cell tumor, or small cell carcinoma can also resemble lymphoma.

Myeloid neoplasms, including acute myeloid leukemia and myeloid (granulocytic) sarcoma, may involve the ovary and rarely constitute the initial clinical presentation of the disease. At the time of diagnosis of myeloid sarcoma, leukemia may or may not involve the peripheral blood and bone marrow; if not present, it usually develops subsequently. Some of these tumors exhibit a characteristic green color (‘chloroma’). Microscopic examination reveals a diffuse growth pattern with a prominent ‘single file’ arrangement of the tumor cells (Figure 30.49). In contrast to lymphoma cells, the cells of myeloid (granulocytic) sarcoma have more finely dispersed nuclear chromatin and more abundant cytoplasm. Myeloid differentiation can be demonstrated by the chloroacetate esterase stain. Immunostains for myeloperoxidase, lysozyme, and CD68 are positive.112 B- and T-cell markers, such as CD20 and CD3, are negative.

Peritoneal Tumors

Secondary ovarian involvement by malignant mesothelioma is common and is usually limited to the surface of the ovary or the superficial stroma (Figure 30.50). Occasionally, however, the ovary is extensively involved and the clinical picture simulates that of ovarian cancer.113 Microscopically, malignant mesotheliomas are characterized by tubular, papillary, and solid patterns and relatively uniform cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 30.49). Rare tumors with an exclusive sheet-like pattern containing polygonal cells may be confused with ectopic decidual reaction. In routinely stained sections, mesotheliomas are usually readily distinguishable from serous carcinoma by their pattern of growth and cytologic features, although histochemical or immunohistochemical stains are sometimes necessary to confirm the diagnosis. In contrast to adenocarcinomas, mesotheliomas lack neutral mucins (digested PAS negative) and contain hyaluronic acid within vacuoles (Alcian blue positive, hyaluronidase sensitive). Hyaluronic acid, however, may leach from formalin-fixed tumors, resulting in false-negative staining. The most useful immunohistochemical markers are the BerEp4-defined surface glycoprotein, which is positive in serous carcinomas but negative in mesothelioma, and calretinin (Figure 30.51), CK5/6, and thrombomodulin, all three of which are positive in mesothelioma but negative in serous carcinomas.114,115 Additionally, no reactivity for CEA, B72.3, Leu-M1, ER, PR, and CA125 favor a diagnosis of mesothelioma over carcinoma.

Figure 30.51 Malignant epithelial mesothelioma involving the ovary. The tumor cells are immunoreactive for calretinin.

Extraovarian primary peritoneal serous carcinomas are tumors histologically identical to serous carcinomas of the ovary that present with peritoneal carcinomatosis and minimal or no ovarian involvement. Most peritoneal serous carcinomas are high grade and fundamentally different from low-grade peritoneal serous carcinomas. The latter tumors are distinguished from serous borderline tumors by the presence of invasion. Compared with ovarian high-grade serous carcinomas, the peritoneal tumors contain less ER and PR, and exhibit a stronger expression of Ki-67, and a higher overexpression of HER-2/neu.116

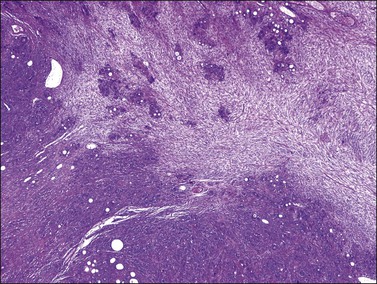

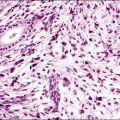

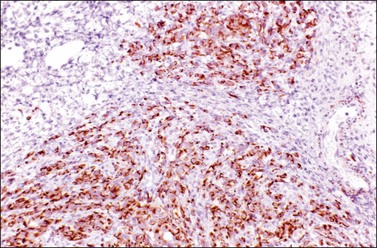

Although desmoplastic small round-cell tumors (DSRCTs) with divergent differentiation occur mainly in young males, a few of these tumors have developed in females and have presented clinically as primary ovarian tumors.117,118 At operation, there was extensive extraovarian disease in all the reported cases, and, despite combination chemotherapy, most patients died of tumor within 2 years of diagnosis. The tumor cells have the translocation t(11;22)(p13;q12), which results in fusion of the Ewing sarcoma and Wilms’ tumor genes (EWS–WT1).119 Microscopically, the metastatic tumor shows discrete aggregates of small cells surrounded by a desmoplastic stroma (Figures 30.52 and 30.53). The tumor cells are small with hyperchromatic nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, and scanty cytoplasm. Mitotic figures are numerous. Since many ovarian tumors are characterized by small cells, there is a wide range of differential diagnoses. A prominent nesting pattern of small cells in a desmoplastic stroma, as well as a young age of the patient, should lead to consideration of this tumor. The immunophenotype of the DSRCT is quite characteristic: the tumor cells stain for CKs (Figure 30.54) and epithelial membrane antigen, for neuron-specific enolase, and for desmin (Figure 30.55). Immunostain for actin is negative.

Figure 30.52 Desmoplastic small round-cell tumor involving the ovary. Round aggregates of small cells are surrounded by a fibromatous stroma.

Figure 30.53 Desmoplastic small round-cell tumor involving the ovary. Elongated aggregates of small round and spindle cells are embedded in a desmoplastic stroma.

Figure 30.54 Desmoplastic small round-cell tumor involving the ovary. The tumor cells are immunoreactive for cytokeratin. Some primary follicles are seen.

Figure 30.55 Desmoplastic small round-cell tumor involving the ovary. Positive immunoreaction for desmin.

Unusual metastases to the ovary have included small cell carcinoma of the lung, adenoid cystic carcinoma of salivary gland origin, neuroblastoma, alveolar and embryonal rhabdomyosarcomas, leiomyosarcoma, angiosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, chondrosarcoma, osteogenic sarcoma, chordoma, and ependymoma (Figures 30.56 and 30.57).3

Extragenital Sarcomas

Sarcomas rarely metastasize to the ovaries and are more likely to be primary tumors at that site. An exception to this is the gastrointestinal stromal tumor.120 The differential diagnoses include cellular and typical fibromas, smooth muscle tumors, and other primary soft-tissue-type tumors. In cases of bilateral tumors or extraovarian disease, immunohistochemistry for c-kit helps to rule out the possibility of a gastrointestinal stromal neoplasm. Leiomyosarcomas from stomach, small bowel, and retroperitoneum may occasionally metastasize to the ovary.96 Also isolated examples of fibrosarcoma of the anterior abdominal wall, sarcoma of the mesentery, angiosarcoma of the heart, osteosarcoma of the maxilla, chondrosarcoma of the rib, Ewing sarcoma of a pubic bone, angiosarcoma,121 alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma,82,122 Ewing sarcoma of the fibula,82 chordoma,123 and malignant hemangiopericytoma.124 In children, rhabdomyosarcoma is said to be the most common sarcoma to spread to ovary.82 Metastatic retinoblastoma is also known.122,125

References

1. Mazur, MT, Hsueh, S, Gersell, DJ. Metastases to the female genital tract. Analysis of 325 cases. Cancer. 1984; 53:1978–1984.

2. Lash, RH, Hart, WR. Intestinal adenocarcinomas metastatic to the ovaries: a clinicopathologic evaluation of 22 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987; 11:114–121.

3. Scully, RE, Young, RH, Clement, PB. Tumors of the ovary, maldeveloped gonads, fallopian tube, and broad ligament. In Atlas of tumor pathology, third series. Fascicle 23. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1998.

4. Ulbright, TM, Roth, LM, Stehman, FB. Secondary ovarian neoplasia. A clinicopathologic study of 35 cases. Cancer. 1984; 53:1164–1174.

5. Young, RH, Scully, RE. Metastic tumours of the ovary. In: Kurman RJ, ed. Blaustein’s pathology of the female genital tract. 4th ed. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1994:939–974.

6. Bullón, A, Arseneau, J, Prat, J, et al. Tubular Krukenberg tumor. A problem in histopathologic diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1981; 5:225–232.

7. Merino, MJ, Edmonds, P, LiVolsi, V. Appendiceal carcinoma metastatic to the ovaries and mimicking primary ovarian tumors. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1985; 4:110–120.

8. Young, RH, Gilks, CB, Scully, RE. Mucinous tumors of the appendix associated with mucinous tumors of the ovary and pseudomyxoma peritonei. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991; 15:415–429.

9. Cuatrecasas, M, Matias-Guiu, X, Prat, J. Synchronous mucinous tumors of the appendix and the ovary associated with pseudomyxoma peritonei: a clinicopathologic study of six cases with comparative analysis of c-Ki-ras mutations. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996; 20:739–746.

10. Ronnett, BM, Kurman, RJ, Shmookler, BM, et al. The morphologic spectrum of ovarian metastases of appendiceal adenocarcinomas. A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of tumors often misinterpreted as primary ovarian tumors or metastatic tumors from other gastrointestinal sites. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997; 21:1144–1155.

11. Young, RH, Hart, WR. Metastases from carcinoma of the pancreas simulating primary mucinous tumors of the ovary: A report of seven cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989; 13:748–756.

12. Creasman, WT, Lukeman, J. Role of the fallopian tube in dissemination of malignant cells in corpus cancer. Cancer. 1972; 20:456–457.

13. Pins, MR, Young, RH, Crum, CP, et al. Cervical squamous carcinoma in situ with superficial extension to corpus and tubes and invasion of tubes and ovaries. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1997; 16:272–278.

14. Ronnett, BM, Yemelyanova, AV, Vang, R, et al. Endocervical adenocarcinomas with ovarian metastases. Analysis of 29 cases with emphasis on minimally invasive cervical tumors and the ability of the metastases to simulate primary ovarian neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008; 32:1835–1853.

15. Gagnon, Y, Tetu, B. Ovarian metastases of breast carcinoma. A clinicopathologic study of 59 cases. Cancer. 1989; 64:892–898.

16. Petru, E, Pickel, H, Heydarfadai, M, et al. Nongenital cancers metastatic to the ovary. Gynecol Oncol. 1992; 44:83–86.

17. Savey, L, Lasser, P, Castaigne, D, et al. Krukenberg tumors. Analysis of a series of 28 cases. J Chir (Paris). 1996; 133:427–431.

18. Mrad, K, Morice, P, Fabre, A, et al. Krukenberg tumor: a clinico-pathological study of 15 cases. Ann Pathol. 2000; 20:202–206.

19. Le Bouedec, G, de Latour, M, Levrel, O, Dauplat, J. Krukenberg tumors of breast origin. 10 cases. Presse Med. 1997; 26:454–457.

20. Kim, SH, Kim, WH, Park, KJ, et al. CT and MR findings of Krukenberg tumors: comparison with primary ovarian tumors. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1996; 20:393–398.

21. Ha, HK, Baek, SY, Kim, SH, et al. Krukenberg’s tumor of the ovary: MR imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995; 164:1435–1439.

22. Young, RH, Scully, RE. Metastatic tumors in the ovary: a problem-oriented approach and review of the recent literature. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1991; 8:250–276.

23. Seidman, JD, Kurman, RJ, Ronnett, BM. Incidence in routine practice with a new approach to improve intraoperative diagnosis. Primary and metastatic mucinous adenocarcinomas in the ovaries. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003; 27:985–993.

24. Khunamornpong, S, Suprasert, PS, Pojchamarnwiputh, S, et al. Primary and metastatic mucinous adenocarcinomas of the ovary: evaluation of the diagnostic approach using tumor size and laterality. Gynecol Oncol. 2006; 101:152–157.

25. Stewart, CJR, Brennan, BA, Hammond, IG, et al. Accuracy of frozen section in distinguishing primary ovarian neoplasia from tumors metastatic to the ovary. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2005; 24:356–362.

26. Yemelyanova, AV, Vang, R, Judson, K, et al. Distinction of primary and metastatic mucinous tumors involving the ovary: analysis of size and laterality data by primary site with reevaluation of an algorithm for tumor classification. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008; 32:128–138.

27. Abu-Rustum, NR, Barakat, RR, Curtin, JP. Ovarian and uterine disease in women with colorectal cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1997; 89:85–87.

28. Lewis, MR, Deavers, MT, Silva, EG, Malpica, A. Ovarian involvement by metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma. Still a diagnostic challenge. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006; 30:177–184.

29. Judson, K, McCormick, C, Vang, R, et al. Women with undiagnosed colorectal adenocarcinomas presenting with ovarian metastases: clinicopathologic features and comparison with women having known colorectal adenocarcinomas and ovarian involvement. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2008; 27:182–190.

30. Scully, RE, Richardson, GS. Luteinization of the stroma of metastatic cancer involving the ovary and its endocrine significance. Cancer. 1961; 14:827–840.

31. Lee, KR, Young, RH. The distinction between primary and metastatic mucinous carcinomas of the ovary: gross and histologic findings in 50 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003; 27:281–292.

32. Young, RH, Hart, WR. Metastatic intestinal carcinomas simulating primary ovarian clear cell carcinoma and secretory endometrioid carcinoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of five cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998; 22:805–815.

33. Berezowski, K, Stastny, JK, Kornstein, MJ. Cytokeratins 7 and 20 and carcinoembryonic antigen in colonic and ovarian carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 1996; 9:426–429.

34. DeCostanzo, DC, Elias, JM, Chumas, JC. Necrosis in 84 ovarian carcinomas: a morphologic study of primary versus metastatic colonic carcinoma with a selective immunohistochemical analysis of cytokeratin subtypes and carcinoembryonic antigen. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1997; 16:245–249.

35. Ji, H, Isacson, C, Seidman, J, et al. Cytokeratins 7 and 20, Dpc4, and MUC5AC in the distinction of metastatic mucinous carcinomas in the ovary from primary ovarian mucinous tumors: Dpc4 assists in identifying metastatic pancreatic carcinomas. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2002; 21:391–400.

36. Wang, NP, Zee, S, Zarbo, RJ, et al. Coordinate expression of cytokeratins 7 and 20 defines unique subsets of carcinomas. Appl Immunohistochem. 1995; 3:99–107.

37. Wauters, CCAP, Smedts, F, Gerrits, LGM, et al. Keratins 7 and 20 as diagnostic markers of carcinomas metastatic to the ovary. Hum Pathol. 1995; 26:852–855.

38. Park, SY, Kim, HS, Hong, EK, Kim, WH. Expression of cytokeratins 7 and 20 in primary carcinomas of the stomach and colorectum and their value in the differential diagnosis of metastatic carcinomas to the ovary. Hum Pathol. 2002; 33:1078–1085.

39. Dabbs, DJ, Sturtz, K, Zaino, RJ. The immunohistochemical discrimination of endometrioid carcinomas. Hum Pathol. 1996; 27:172–177.

40. Logani, S, Oliva, E, Arnell, PM, et al. Use of novel immunohistochemical markers expressed in colonic adenocarcinoma to distinguish primary ovarian tumors from metastatic colorectal carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2005; 18:19–25.

41. Vang, R, Gown, AM, Wu, LSF, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of CDX2 in primary ovarian mucinous tumors and metastatic mucinous carcinomas involving the ovary: comparison with CK20 and correlation with coordinate expression of CK7. Mod Pathol. 2006; 19:1421–1428.

42. McCluggage, WG. Immunohistochemical markers as a diagnostic aid in ovarian pathology. Diagn Histopathol. 2008; 14:335–351.

43. Lerwill, MF, Young, RH. Ovarian metastases of intestinal-type gastric carcinoma. A clinicopathologic study of 4 cases with contrasting features to those of the Krukenberg tumor. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006; 31:1382–1388.

44. Scully, RE, Sobin, LH. World Health Organization: histological typing of ovarian tumours, 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1999.

45. Kiyokawa, T, Young, RH, Scully, RE. Krukenberg tumors of the ovary. A clinicopathologic analysis of 120 cases with emphasis on their variable pathologic manifestations. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006; 31:277–299.

46. Holtz, F, Hart, WR. Krukenberg tumors of the ovary. A clinicopathologic analysis of 27 cases. Cancer. 1982; 50:2438–2447.

47. Robboy, SJ, Scully, RE, Norris, HJ. Carcinoid metastatic to the ovary. A clinocopathologic analysis of 35 cases. Cancer. 1974; 33:798–811.

48. Rabban, JT, Lerwill, MF, McCluggage, WG, et al. Primary ovarian carcinoid tumors may express CDX-2: a potential pitfall in distinction from metastatic intestinal carcinoid tumors involving the ovary. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2009; 28:41–48.

49. Curtin, JP, Barakat, RR, Hoskins, WJ. Ovarian disease in women with breast cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 1994; 84:449–452.

50. Young, RH, Carey, RW, Robboy, SJ. Breast carcinoma masquerading as a primary ovarian neoplasm. Cancer. 1981; 48:210–212.

51. Harris, M, Howell, A, Chrissohou, M, et al. A comparison of the metastatic pattern of infiltrating lobular carcinoma and infiltrating duct carcinoma of the breast. Br J Cancer. 1984; 50:23–30.

52. Monteagudo, C, Merino, MJ, LaPorte, N, Neumann, RD. Value of gross cystic disease fluid protein-15 in distinguishing metastatic breast carcinoma among poorly differentiated neoplasms involving the ovary. Hum Pathol. 1991; 22:368–372.

53. Brown, RJ, Campagna, LB, Dunn, JK, Cagle, PT. Immunohistochemical identification of tumor markers in metastatic adenocarcinoma: a diagnostic adjunct in the determination of primary site. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997; 107:12–19.

54. Bhargava, R, Beriwal, S, Dabbs, DJ. Mammaglobin vs GCDFP-15. An immunohistologic validation survey for sensitivity and specificity. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007; 127:103–113.

55. Sasaki, E, Tsunoda, N, Hatanaka, Y, et al. Breast-specific expression of MGB1/mammaglobin: an examination of 480 tumors from various organs and clinicopathological analysis of MGB1-positive breast cancers. Mod Pathol. 2007; 20:208–214.

56. Onuma, K, Dabbs, DJ, Bhargava, R. Mammaglobin expression in the female genital tract: immunohistochemical analysis in benign and neoplastic endocervix and endometrium. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2008; 27:418–425.

57. Nonaka, D, Chiriboga, L, Soslow, RA. Expression of PAX8 as a useful marker in distinguishing ovarian carcinomas from mammary carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008; 32:1566–1571.

58. Young, RH, Hart, WR. Metastases from carcinomas of the pancreas simulating primary mucinous tumors of the ovary: a report of seven cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989; 13:748–756.

59. Young, RH, Scully, RE. Ovarian metastases from carcinoma of the gallbladder and extrahepatic bile ducts simulating primary tumors of the ovary: a report of six cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1990; 9:60–72.

60. Young, RH, Gersell, DJ, Clement, PB, Scully, RE. Hepatocellular carcinoma metastatic to the ovary. A report of three cases discovered during life with discussion of the differential diagnosis of hepatoid tumors of the ovary. Hum Pathol. 1992; 23:574–580.

61. Vakiani, E, Young, RH, Carcangiu, ML, Klimstra, DS. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas metastatic to the ovary. A report of 4 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008; 32:1540–1545.

62. Khunamornpong, S, Lerwill, MF, Siriaunkgul, S, et al. Carcinoma of extrahepatic bile ducts and gallbladder metastatic to the ovary: a report of 16 cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2008; 27:366–379.

63. Pitman, MB, Triratanachat, S, Young, RH, Oliva, E. Hepatocyte paraffin 1 antibody does not distinguish primary ovarian tumors with hepatoid differentiation from metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2003; 23:58–64.

64. Prayson, RA, Hart, WR, Petras, RE. Pseudomyxoma peritonei: a clinicopathologic study of 19 cases with emphasis on site of origin and nature of associated ovarian tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994; 18:591–603.

65. Ronnett, BM, Kurman, RJ, Zahn, CM, et al. Pseudomyxoma peritonei in women: a clinicopathologic analysis of 30 cases with emphasis on site of origin, prognosis, and relationship to ovarian mucinous tumors of low malignant potential. Hum Pathol. 1995; 26:509–524.

66. Merino, MJ, Edmonds, P, LiVolsi, V. Appendiceal carcinoma metastatic to the ovaries and mimicking primary ovarian tumors. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1985; 4:110–120.

67. Hristov, AC, Young, RH, Vang, R, et al. Ovarian metastases of appendiceal tumors with goblet cell carcinoid-like and signet ring cell patterns: A report of 30 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007; 31:1502–1511.

68. Szych, C, Staebler, A, Connolly, DC, et al. Molecular genetic evidence supporting the clonality and appendiceal origin of Pseudomyxoma peritonei in women. Am J Pathol. 1999; 154:1849–1855.

69. Insabato, L, DeRosa, G, Franco, R, et al. Ovarian metastasis from renal cell carcinoma: a report of three cases. Int J Surg Pathol. 2003; 11:309–312.

70. Spencer, JR, Eriksen, B, Garnett, JE. Metastatic renal tumor presenting as ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Urology. 1993; 41:582–584.

71. Vara, A, Madrigal, B, Veiga, M, et al. Bilateral ovarian metastases from renal clear cell carcinoma. Acta Oncol (Stockh). 1998; 37:379–380.

72. Young, RH, Hart, WR. Renal cell carcinoma metastatic to the ovary: a report of three cases emphasizing possible confusion with ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1992; 11:96–104.

73. Cameron, RI, Ashe, P, O’Rourke, DM, et al. A panel of immunohistochemical stains assists in the distinction between ovarian and renal clear cell carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2003; 22:272–276.

74. Leroy, X, Farine, MO, Buob, D, et al. Diagnostic value of cytokeratin 7, CD10 and mesothelin in distinguishing ovarian clear cell carcinoma from metastasis of renal clear cell carcinoma. Histopathology. 2007; 51:846–876.

75. Ohta, Y, Suzuki, T, Shiokawa, A, et al. Expression of CD10 and cytokeratins in ovarian and renal clear cell carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2005; 24:239–245.

76. Gokden, N, Gokden, M, Phan, DC, McKenney, JK. The utility of PAX-2 in distinguishing metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma from its morphologic mimics. An immunohistochemical study with comparison to renal cell carcinoma marker. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008; 32:1462–1467.

77. Young, RH, Scully, RE. Urothelial and ovarian carcinomas of identical cell types: Problems in interpretation. A report of three cases and review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1988; 7:197–211.

78. Oliva, E, Musulén, E, Prat, J, Young, RH. Transitional cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis with symptomatic ovarian metastases. Int J Surg Pathol. 1995; 2:231–236.

79. Riedel, I, Czernobilsky, B, Lifschitz-Mercer, B, et al. Brenner tumors but not transitional cell carcinomas of the ovary show urothelial differentiation: immunohistochemical staining of urothelial markers, including cytokeratins and uroplakins. Virchows Arch. 2001; 438:181–191.

80. Logani, S, Oliva, E, Amin, MB, et al. Immunoprofile of ovarian tumors with putative transitional cell (urothelial) differentiation using novel urothelial markers. Histogenic and diagnostic implications. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003; 27:1434–1441.

81. Meyer, WH, Yu, GW, Milvenan, ES, et al. Ovarian involvement in neuroblastoma. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1979; 7:49–54.

82. Sty, JR, Kun, LE, Casper, JT. Bone scintigraphy in neuroblastoma with ovarian metastasis. Wis Med J. 1980; 79:28–29.

83. Young, RH, Kozakewich, HPW, Scully, RE. Metastatic ovarian tumors in children: a report of 14 cases and review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1993; 12:8–19.

84. Kurek, R, Von Knobloch, R, Feek, U, et al. Local recurrence of an oncocytic adrenocortical carcinoma with ovary metastasis. J Urol. 2001; 166:985.

85. Fitzgibbons, PL, Martin, SE, Simmons, TJ. Malignant melanoma metastatic to the ovary. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987; 11:959–964.

86. Gupta, D, Deavers, MT, Silva, EG, et al. Malignant melanoma involving the ovary. A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 23 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004; 28:771–780.

87. Young, RH, Scully, RE. Malignant melanoma metastatic to the ovary: a clinicopathologic analysis of 20 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991; 15:849–860.

88. Irving, JA, Young, RH. Lung carcinoma metastatic to the ovary: a clinicopathologic study of 32 cases emphasizing their morphologic spectrum and problems in differential diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005; 29:997–1006.

89. Reis-Filho, JS, Carrilho, C, Valenti, C, et al. Is TTF1 a good immunohistochemical marker to distinguish primary from metastatic lung adenocarcinomas? Pathol Res Pract. 2000; 196:835–840.

90. Baker, PM, Oliva, E. Immunohistochemistry as a tool in the differential diagnosis of ovarian tumors: an update. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2005; 24:39–55.

91. Bing, Z, Adegboyega, PA. Metastasis of small cell carcinoma of lung into an ovarian mucinous neoplasm: immunohistochemistry as a useful ancillary technique for diagnosis and classification of rare tumors. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2005; 13:104–107.

92. Yeh, KY, Chang, JW, Hsueh, S, et al. Ovarian metastasis originating from bronchioloalveolar carcinoma: a rare presentation of lung cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2003; 33:404–407.

93. Young, RH, Gersell, DJ, Roth, LM, Scully, RE. Ovarian metastases from cervical carcinomas other than pure adenocarcinomas. A report of 12 cases. Cancer. 1993; 71:407–418.

94. Eichhorn, JH, Young, RH, Scully, RE. Nonpulmonary small cell carcinomas of extragenital origin metastatic to the ovary. Cancer. 1993; 71:177–186.

95. Bott-Kothari, T, Aron, BS, Bejarano, P. Malignant thymoma with metastases to the gastrointestinal tract and ovary: a case report and literature review. Am J Clin Oncol. 2000; 23:140–142.

96. Young, RH, Scully, RE. Sarcomas metastatic to the ovary: a report of 21 cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1990; 9:231–252.

97. Young, RH, Scully, RE. Mucinous ovarian tumors associated with mucinous adenocarcinomas of the cervix. A clinicopathological analysis of 16 cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1988; 7:99–111.

98. Kaminski, PF, Norris, HJ. Coexistence of ovarian neoplasms and endocervical adenocarcinoma. Obstet Gynecol. 1984; 64:553–556.

99. LiVolsi, VA, Merino, MJ, Schwartz, PE. Coexistent endocervical adenocarcinoma and mucinous adenocarcinoma of ovary: a clinicopathological study of four cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1983; 1:391–402.

100. Elishaev, E, Gilks, CB, Miller, D, et al. Synchronous and metachronous endocervical and ovarian neoplasms. Evidence supporting interpretation of the ovarian neoplasms as metastatic endocervical adenocarcinomas simulating primary ovarian surface epithelial neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005; 29:281–294.

101. Ronnett, BM, Yemelyanova, AV, Vang, R, et al. Endocervical adenocarcinomas with ovarian metastases. Analysis of 29 cases with emphasis on minimally invasive cervical tumors and the ability of the metastases to simulate primary ovarian neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008; 32:1835–1853.

102. Young, RH, Gersell, DJ, Roth, LM, Scully, RE. Ovarian metastases from cervical carcinomas other than pure adenocarcinomas. A report of 12 cases. Cancer. 1993; 71:407–418.

103. Nguyen, L, Brewer, CA, DiSaia, PJ. Ovarian metastasis of stage 1B1 squamous cell cancer of the cervix after radical parametrectomy and oophoropexy. Gynecol Oncol. 1998; 68:198–200.

104. Alvarado-Cabrero, I, Young, RH, Vamvakas, EC, Scully, RE. Carcinoma of the fallopian tube: a clinicopathological study of 105 cases with observations on staging and prognostic factors. Gynecol Oncol. 1999; 72:367–379.

105. Baekelandt, M, Jorunn, NA, Kristensen, GB, et al. Carcinoma of the fallopian tube. Cancer. 2000; 89:2076–2084.

106. Piek, JM, van Diest, PJ, Zweemer, RP, et al. Dysplastic changes in prophylactically removed fallopian tubes of women predisposed to developing ovarian cancer. J Pathol. 2001; 195:451–456.

107. Piek, JM, van Diest, PJ, Zweemer, RP, et al. Tubal ligation and risk of ovarian cancer. Lancet. 2001; 358:844.

108. Kindelberger, DW, Lee, Y, Miron, A, et al. Intraepithelial carcinoma of the fimbria and pelvic serous carcinoma: evidence for a causal relationship. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007; 31:161–169.

109. Lee, Y, Miron, A, Drapkin, R, et al. A candidate precursor to serous carcinoma that originates in the distal fallopian tube. J Pathol. 2007; 211:26–35.

110. Dimopoulos, MA, Daliani, D, Pugh, W, et al. Primary ovarian non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: outcome after treatment with combination chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 1997; 64:446–450.

111. Monterroso, V, Jaffe, ES, Merino, MJ, Medeiros, LJ. Malignant lymphomas involving the ovary. A clinicopathologic analysis of 39 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993; 17:154–170.

112. Oliva, E, Ferry, JA, Young, RH, et al. Granulocytic sarcoma of the female genital tract. A clinicopathologic study of 11 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997; 21:1156–1165.

113. Clement, PB, Young, RH, Scully, RE. Malignant mesotheliomas presenting as ovarian masses. A report of nine cases, including two primary ovarian mesotheliomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996; 20:1067–1080.

114. Ordonez, NG. Role of immunohistochemistry in distinguishing epithelial peritoneal mesotheliomas from peritoneal and ovarian serous carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998; 22:1203–1214.

115. Yaziji, H, Gown, AM. Immunohistochemical analysis of gynecologic tumors. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2001; 20:64–78.

116. Halperin, R, Zehavi, S, Hadas, E, et al. Immunohistochemical comparison of primary peritoneal and primary ovarian serous papillary carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2001; 20:341–345.

117. Young, RH, Eichhorn, JH, Dickersin, GR, Scully, RE. Ovarian involvement by the intra-abdominal desmoplastic small round cell tumor with divergent differentiation: a report of three cases. Hum Pathol. 1992; 23:454–464.

118. Zaloudek, C, Miller, TR, Stern, JR. Desmoplastic small cell tumor of the ovary: a unique polyphenotypic tumor with an unfavorable prognosis. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1995; 14:260–265.

119. Ladanyi, M, Gerald, W. Fusion of the EWS and WT1 genes in the desmoplastic small round cell tumor. Cancer Res. 1994; 54:2837–2840.

120. Irving, JA, Lerwill, MF, Young, RH. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors metastatic to the ovary. A report of five cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005; 29:920–926.

121. Patel, T, Ohri, SK, Sundaresan, M, et al. Metastatic angiosarcoma of the ovary. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1991; 17:295–299.

122. McCarville, MB, Hill, DA, Miller, BE, Pratt, CB. Secondary ovarian neoplasms in children: imaging features with histopathologic correlation. Pediatr Radiol. 2001; 31:358–364.

123. Zukerberg, LR, Young, RH. Chordoma metastatic to the ovary. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1990; 114:208–210.

124. Begum, M, Katabuchi, H, Tashiro, H, et al. A case of metastatic malignant hemangiopericytoma of the ovary: recurrence after a period of 17 years from intracranial tumor. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2002; 12:510–514.

125. Moshfeghi, DM, Wilson, MW, Haik, BG, et al. Retinoblastoma metastatic to the ovary in a patient with Waardenburg syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002; 133:716–718.