Vulvar Dermatoses and Infections

Common Dermatoses Affecting the Vulva

Less Common Dermatoses that Frequently Involve the Vulva

Other Inflammatory Diseases Affecting the Vulva

Vulvar Infections and Infestations

Introduction

The most common diseases affecting the vulva are dermatologic,1–7 but the clinicians caring for patients with these complaints are usually gynecologists or family practitioners who may lack sophisticated diagnostic and therapeutic skills in skin diseases. Conversely, dermatologists may have interest and expertise in a subset of diseases in this organ. In summary, no single specialist is generally well trained to care for the full spectrum of vulvar diseases. Multidisciplinary clinics, to which different specialists bring their expertise, are often the best forum to efficiently diagnose and treat acute or chronic vulvar diseases.8,9

In response to the complexity of vulvar disorders, the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISVVD) was founded with one objective: to facilitate clear communication between clinicians and pathologists caring for patients with neoplastic and non-neoplastic vulvar diseases. Accordingly, it discarded its 1987 classification, replacing it in 2006 (Table 3.1) with an entirely different classification based on histopathology.10,11 And in 2011, a new clinical based classification of inflammatory vulvar diseases was published to assist the clinician to reach a diagnosis based only on clinical findings (see glossaries at the end of this chapter). Currently, the ISSVD considers both classifications as complementary of each other.

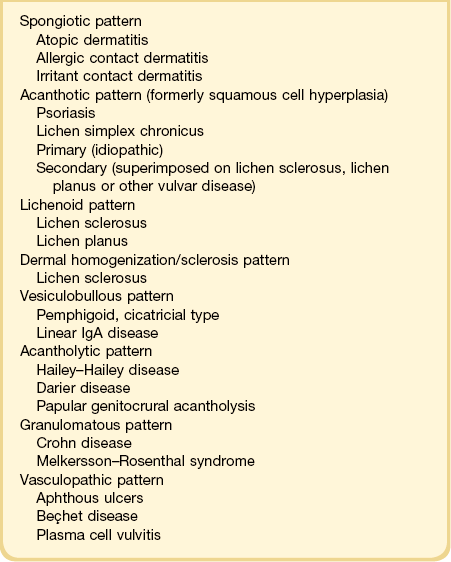

Table 3.1

2006 ISSVD Classification of Vulvar Dermatoses:10,11 Pathologic Subsets and Their Clinical Correlates

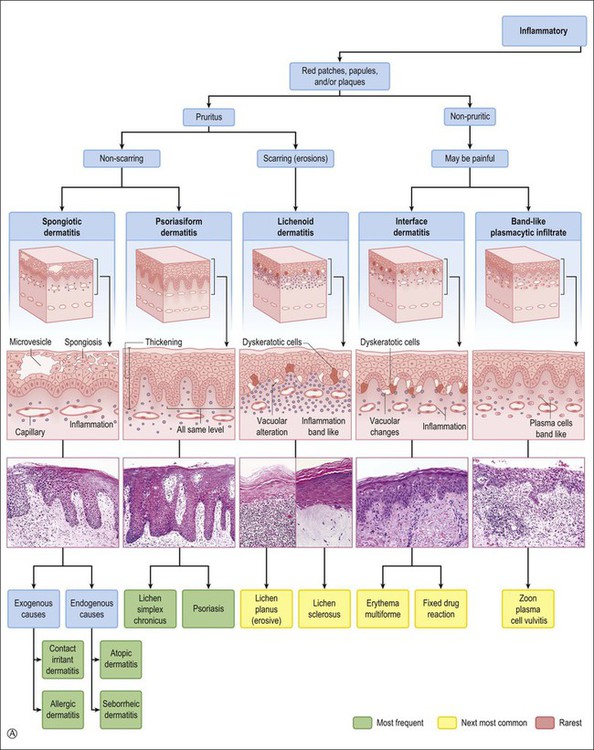

This chapter utilizes a multidisciplinary approach. The diseases are organized in order of frequency and classified with a clinical perspective using the type of lesion (patch, papule, nodule, etc.) and the symptoms produced (itch, etc.), combined with the histopathologic pattern of inflammation (Figure 3.1). Both vulvar and extravulvar manifestations are covered. Not uncommonly, the latter features are the key to a correct diagnosis.

Common Dermatoses Affecting the Vulva

Spongiotic Dermatitis (Eczemas)

General Clinical and Pathologic Features of Spongiotic Dermatitis

Acute Spongiotic Dermatitis.

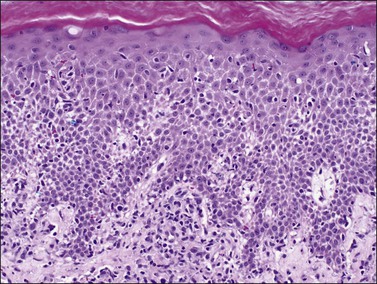

The term ‘eczema’ derives from the Greek ekzein ‘to boil over,’ reflecting the clinical appearance of acute lesions. Clinically, it exhibits erythematous macules, papules, and plaques (Figure 3.2). With increasing degrees of spongiosis, lesions become vesicular or bullous and begin to weep or to ooze. The vesicles frequently progress to rupture, and their contents dry to form a surface crust. In the biopsy specimen the epidermis shows a variable amount of spongiosis, hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis, and exocytosis of inflammatory cells. If the spongiosis is considerable, the fluid will collect in intraepidermal vesicles that may contain lymphocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, and Langerhans cells. Mild papillary dermal edema leading to separation of collagen fibers can be seen in association with telangiectatic vessels. The superficial vascular plexus shows a perivascular mixed inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils. This basic pattern of acute spongiotic dermatitis is altered by scratching or superimposed infections (impetiginization). The former produces excoriations or lichen simplex chronicus (see the following section); the latter is associated with neutrophils in the stratum corneum. Acute inflammation in the stratum corneum should prompt the pathologist to request special stains for bacterial (Brown–Brenn) and fungal (periodic acid–Schiff, PAS, and Gomori methenamine silver, GMS) forms.

Chronic Spongiotic Dermatitis.

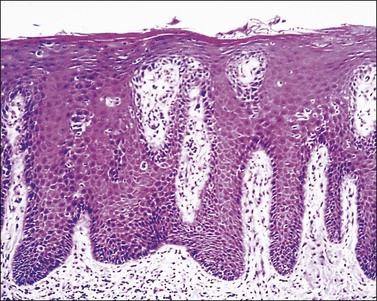

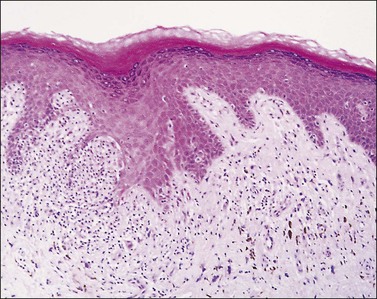

Clinically the skin exhibits a leathery appearance with accentuation of skin markings (lichenification). The skin also changes from red (characteristic of acute spongiotic dermatitis) to brown or hyperpigmented, particularly in racially dark individuals. Scratching from intense pruritus produces excoriations where the surface has been traumatized. Histologically there is variable hyperplasia of the epidermis (acanthosis) with overlying hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis. The elongated rete ridges are separated by a papillary dermis with prominent capillaries and thick collagen fibers arranged perpendicular to the surface. Lymphocytes predominantly are found around upper dermal vessels. In certain biopsy specimens, in the previously described background of chronic dermatitis, there are features associated with acute inflammation, specifically a notable degree of spongiosis. This coexistence of acute and chronic histologic findings is called subacute spongiotic dermatitis (Figure 3.3).

Clinical Patterns of Vulvar Spongiotic Dermatitis

Endogenous Vulvar Spongiotic Dermatitis.

The two most common endogenous dermatitides are atopic dermatitis and seborrheic dermatitis. Both diseases can show the entire spectrum of eczematous lesions ranging from erythematous scaly areas to oozing to vesicle formation, ending in lichenification. Few physicians see the acute phase. Most patients seek medical attention only during the subacute to chronic phase. Commonly, the correct diagnosis depends on identifying more distinctive extragenital lesions.

Exogenous Vulvar Spongiotic Dermatitis.

The two most common forms of spongiotic dermatitis with an exogenous cause are irritant contact dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis.12–16 The acute clinical presentations of allergic and irritant contact dermatitis have significant overlap and with time both evolve to lichen simplex chronicus.

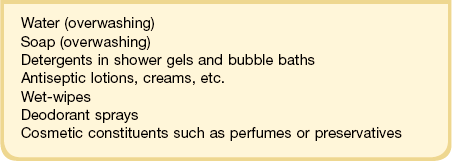

occurs when damage to the cutaneous barrier function exceeds the skin’s repair mechanisms.12–14 This dermatitis is an inflammatory reaction to direct toxic effects of a chemical, physical, or mechanical agent. Irritants may remove surface lipids and water-holding substances, damage cell membranes, denature keratins, exert direct cytotoxic effects, liberate cytokines, etc. Vulvar tissue structure, hydration, occlusion, and friction may increase its propensity to inflammation.17 Irritant contact dermatitis of the vulva occurs most commonly in the form of diaper dermatitis due to urine; this can also occur in adult women experiencing stress incontinence. The most common contact irritants causing vulvar dermatitis are listed in Table 3.2. Contact irritant dermatitis clinically presents with sharply demarcated, erythematous papules and plaques that may be weeping (Figures 3.3 and 3.4) and eroded if acute, or lichenified in chronic cases (see the section Lichen simplex chronicus).18 The diagnosis is confirmed when the culprit is eliminated and the rash disappears.

is a cell-mediated type IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction.12,16 The rash develops 48–72 hours after exposure to the allergen. After sensitization, the patient develops allergic contact dermatitis upon each subsequent exposure. Although one exposure may be sufficient to develop the initial dermatitis, most frequently clinical reactivity becomes manifest only after repetitive exposures. The dermatitis lasts for about 2–3 weeks. As a general rule, infants under five and elderly persons are less liable to develop allergic contact dermatitis as their immune systems tend not to develop type IV hypersensitivity reactions to antigens. If episodes are continuous, a patch test may be useful to study the reactants. Table 3.3 lists the common causes of vulvar allergic dermatitis.

Hints on Histopathologic Interpretation of Vulvar Spongiotic Dermatitis

Biopsy is rarely obtained on acute lesions of either irritant or allergic contact dermatitis. In such cases, the pathologist’s main contribution is to confirm the clinical suspicion of spongiotic dermatitis, and to rule out any other underlying dermatoses such as candidiasis or psoriasis. Performance of fungal stains for vulvar dermatitis can virtually always be justified. Rarely can the histopathologist distinguish the exogenous from the endogenous types with certainty.15 The cause is more likely to be identified after a detailed clinical history and an expert dermatologic examination. However, certain histologic features may point toward a particular entity such as the following:

• Keratin changes. Parakeratosis, particularly when also containing the nuclear remnants of neutrophils, should suggest psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, or a fungal infection. The location of parakeratosis around the follicular ostia, and spongiosis accentuated in the epithelium of the follicular infundibula, point toward seborrheic dermatitis.

• Keratinocytes. Focal keratinocyte ballooning and apoptosis suggests irritant contact dermatitis. Extensive keratinocyte necrosis, however, suggests erythema multiforme, fixed drug eruption, or dermatitis artefacta.

• Spongiosis. Exocytosis of eosinophils into the epidermis suggests fungal infection, allergic contact dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, or drug reaction (or, more rarely, cicatricial pemphigoid or pemphigus vegetans). Neutrophils suggest fungal infection or psoriasis. Increased numbers of Langerhans cells suggest allergic contact dermatitis.

• Dermal infiltrate. Eosinophils suggest allergic contact dermatitis. Marked dermal edema and dilatation of lymphatics suggest an urticarial reaction to systemic or topical drugs.

Chronic Dermatitides

Lichen Simplex Chronicus (Formerly Squamous Cell Hyperplasia or Hyperplastic Dystrophy)

Clinical Features

Lichen simplex chronicus is now considered to be equivalent to squamous cell hyperplasia by the ISSVD.19 Lichen simplex chronicus manifests as thick, scaly plaques arising after rubbing and scratching in response to pruritus. The areas most frequently affected are the mons pubis and labia majora. These cutaneous changes may be the end point of various types of eczematous dermatitis or be superimposed upon other inflammatory processes (lichen planus, psoriasis, lichen sclerosus, etc.). Sometimes the original process that started the chronic itch/scratch cycle, perpetuating the lichen simplex chronicus changes, may have resolved by the time of the biopsy (i.e., an episode of allergic contact dermatitis, an infection with Candida, etc.). Clinically, the presence of thick skin with enhanced cutaneous markings (Figure 3.5) is encompassed by the term ‘lichenification,’ referring to the rough surface of lichen overgrowing smooth-surfaced rocks. Excoriations and secondary infections may result from the scratching. The pathogenesis of this disorder remains incompletely understood.

Microscopic Features

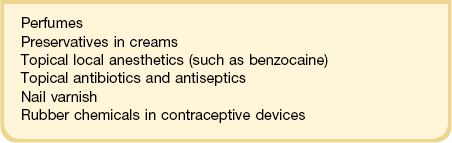

The histologic features of lichen simplex chronicus are epidermal acanthosis with superficial dermal fibrosis and variable chronic inflammation (Figure 3.6). Hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis may be present. The dermal collagen bundles are thickened and tend to be vertically oriented. There is an inflammatory infiltrate, predominately of lymphocytes in the superficial dermis. The changes are otherwise nonspecific, and the diagnosis is made by exclusion of other dermatoses. When inflammatory exocytosis is marked, special stains for fungal forms (PAS and GMS) or bacteria are particularly recommended.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis (psoriasis vulgaris) is a chronic, relapsing, inflammatory dermatosis affecting 1–2% of the American population.20 Psoriasis is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait (diathesis) with incomplete penetrance. Four main genetic loci appear associated with this disease (on chromosomes 17q, 4q, 1q, and 6p).

Clinical Features

The most typical clinical presentation is as well-demarcated, red to salmon-colored plaques with loosely adherent, silver scales affecting the extensor surfaces of the extremities (elbows and knees), sacral region, scalp, and nails. The vulva and perineum are involved frequently in combination with typical lesions elsewhere on the body. Psoriasis is infrequently confined solely to the vulva with a reported incidence of 2–5% of psoriatic patients.20 In the vulva and other intertriginous areas, the silvery scales are lost.21 The disease affects hair-bearing areas (mons pubis and labia majora), whereas the labia minora are spared. The intense erythema and the well-demarcated borders help to separate psoriasis from eczema. The lesions frequently are symmetric and may persist for years. Persistent, painful intergluteal and perianal fissuring can be a serious complication. Often the diagnosis is established with certainty after typical lesions develop elsewhere on the body.

Microscopic Features

The epidermal changes are hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and elongation of the rete ridges to an even length with club-shaped tips of rete ridges, hypogranulosis, and collections of polymorphonuclear leukocytes within the stratum corneum (Munro abscesses) and epidermis (spongiform pustules of Kogoj). Mitotic figures are found at different levels of the epidermis reflecting the significantly increased rate of epithelial turnover. The papillary dermis shows edema with irregularly dilated vessels with a minimal lymphocytic infiltrate and scattered neutrophils (Figure 3.7). Coexistence of staphylococcal infection, repeated scratching, trauma, and chronicity, as well as partial treatment with topical steroids, can affect the histologic features.

Less Common Dermatoses That Frequently Involve the Vulva

Lichenoid Dermatoses

The two most common conditions in this category are lichen sclerosus and lichen planus.

Lichen Sclerosus

Lichen sclerosus, one of the most common chronic anogenital dermatoses, manifests as thickened and sclerotic dermal collagen.1 Most patients are middle-aged and elderly women.22 Sometimes it is familial.23 Childhood presentation is uncommon, but it is important to remember that it does occur lest it be confused with signs of sexual abuse.24–26 One-fifth of patients show extragenital involvement as hypopigmented wrinkled patches. Extragenital lesions as a rule do not undergo malignant degeneration. On the other hand, genital lesions may coexist with or subsequently develop squamous cell carcinoma.27–30 In the vulva the frequency with which squamous cell carcinoma is associated with long-standing lesions of lichen sclerosus is 3–4%,30 compared with 5.8% in penile lesions (balanitis xerotica obliterans), most of them associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection.31

Clinical Features

The clinical presentation of lichen sclerosus is protean. The initial lesions consist of flat, ivory to white papules that coalesce to form plaques of varying sizes and shapes. The early erythematous lesions with an edematous center impart a white color, and with time transform to the classic sclerotic lesions. The ‘cigarette paper’ atrophy in these lesions refers to the progressively wrinkled, flat or slightly depressed surface (Figure 3.8). The symmetrically involved vulva and anus form the classical ‘figure-of-eight’ or ‘hourglass.’ In the vulva, lichen sclerosus extends to Hart’s line in the vestibule, with the vaginal mucosa uninvolved. Vulvar lesions may combine atrophic and hypertrophic areas, or may develop lichenification secondary to pruritus-related scratching. Early stage of lichen sclerosus may be difficult to separate from lichen planus and some patients with lichen sclerosus may develop introital lichen planus.32 This clinical overlap parallels a similar cytokine response between these two diseases.33

Figure 3.8 Lichen sclerosus. Classic white areas with purpura are present on the labia majora and minora. Partial reabsorption of labia minora is seen.

Lichen sclerosus usually causes severe, intractable itch.24,25 Occasionally, the condition is asymptomatic and discovered incidentally during a routine pelvic examination. Over time, variable degrees of scarring occur at an unpredictable pace and extent. Often the labia minora partially resorb (Figure 3.8). In severe cases, vulvar stenosis, effaced anatomy, and clitoral phimosis occur. Dyspareunia is common.

Early diagnosis and adequate treatment can prevent the distressing symptoms and severe vulvar deformities. Close surveillance facilitates early detection of squamous cell carcinoma.34,35 Biopsy has a double role: first to confirm the diagnosis and second to help exclude a malignancy.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Although the etiology of lichen sclerosus is still unknown, infection may play a potential role, an argument based on the presence of CD8+ and CD57+ lymphocytic infiltrates, a profile usually associated with viral diseases and autoimmune disorders. Direct immunofluorescence studies have shown a deposit of fibrin along the dermoepidermal junction in most of the specimens studied.36 With an indirect fluorescent technique, IgM and C3 were concentrated along the basal lamina of the epithelium.36 Studies of the T-cells within lichen sclerosus have identified monoclonal T-cells that are predominantly cytotoxic CD8+ responsible for the destruction of basal keratinocytes.37 Lichen sclerosus is associated with autoimmune disorders such as vitiligo, pernicious anemia, thyroid disease, etc.38–41 Individual HLA types (DQ7, DQ8, and DQ9) have been detected more frequently in patients with lichen sclerosus.38

Tissue studies of glucose metabolism as well as alkaline phosphatase and adenosine triphosphatase have shown a surprisingly high rate of activity equal to that seen in hyperplastic specimens and greater than that found in normal menopausal skin. The cell cycle protein Ki-67 is present in the basal and many parabasal epithelial cells involved by lichen sclerosus.42 Collagen metabolism is abnormally active and the number of capillaries is reduced.

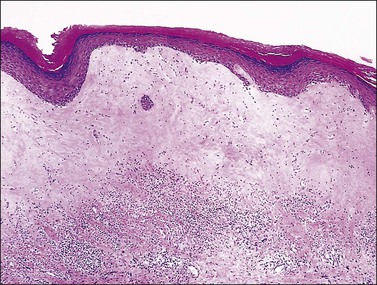

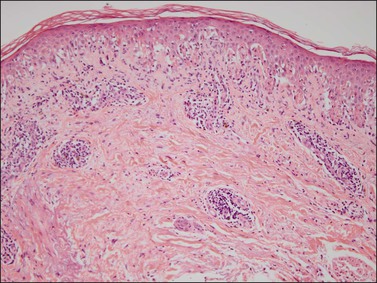

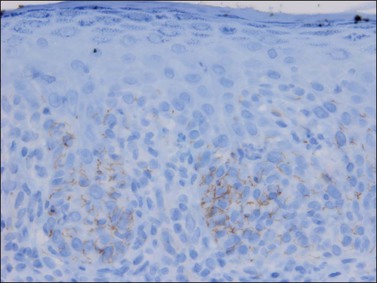

Microscopic Features

Lichen sclerosus affects the epidermis and upper dermis. The microscopic findings can vary considerably depending upon the age of the lesion, scratching, excoriation, and treatment. The main features include a thin epidermis with loss of the rete ridges, an underlying zone of homogeneous collagenized edema of variable thickness, and a band of lymphocytic infiltration beneath this zone (Figures 3.9 and 3.10).43 The squamous epithelium is thinned, but hyperkeratosis may result in some cases from superimposed lichen simplex chronicus. The dermal–epidermal junction may show focal vacuolar change and the basement membrane may fragment, leading to the formation of PAS-positive clumps in the subjacent dermis. Spongiosis may be evident. Mitotic figures are rare or absent. The homogeneous dermal zone usually shows absence of elastic fibers. Both the absence of melanosomes in the keratinocytes and the disappearance of melanocytes contribute to the white clinical appearance.

Clinical Behavior

Lichen sclerosus is a relentless and progressive disease when presenting in most adults, but not uncommonly spontaneously regresses in girls once they reach menarche. Lichen sclerosus sometimes is associated with vulvar squamous carcinoma; however, it is not considered to be a premalignant intraepithelial neoplasm.27–29 In a report of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma, 61% of the patients had lichen sclerosus.44 Symptomatic lichen sclerosus is preceded by carcinoma by a mean of 4 years. Among patients with symptomatic vulvar lichen sclerosus, 9% developed vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) lesions and 21% invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Differentiated (simplex) type VIN and non-HPV-related squamous cell carcinoma have been associated with vulvar lichen sclerosus.45 Increased basal expression of Ki-67 appears to identify those cases with high risk of evolving into squamous cell carcinoma.46,47 Also, aneuploidy has been reported, which correlates with elevated p53 expression.27 Traditional management has relied on the long-term topical application of testosterone or progesterone. Currently, strong topical corticosteroids produce symptomatic relief and, in some cases, resolution of lichen sclerosus.48

Lichen Planus

Lichen planus is a chronic, inflammatory disease of skin and mucous membranes, which occurs most commonly in women older than 40 years of age.1,15,49 Vulvar pruritus and burning are common symptoms; however, the patient may be asymptomatic.50,51 White, lace-like plaques (Wickham striae) involving the oral and vaginal mucosa also may be present (Figure 3.11).52,53 Patients with this condition experience vulvar pain, dyspareunia, and burning. Lichen planus can result in severe introital and vaginal adhesions, scarring, and stenosis.54–56

Clinical Features

Half of the women and one-fourth of the men with cutaneous lichen planus have genital involvement. Unfortunately, it is frequently missed, for several reasons. As a mucocutaneous interface, the vulva can be affected by cutaneous, mucosal, or combined patterns. Thus, the clinical appearance may be highly variable ranging from delicate reticulated papules to an erosive desquamative process involving the vagina and vulva (Figure 3.12).54,55 Within the vulva, the erosive process is typically confined to the vulvar vestibule and commonly involves the vagina. With advancing disease, there is loss and agglutination of the labia minora and prepuce, associated with thinned epithelium, and shrinkage with stenosis of the vaginal introitus.

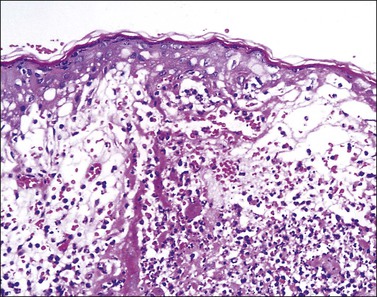

Pathology

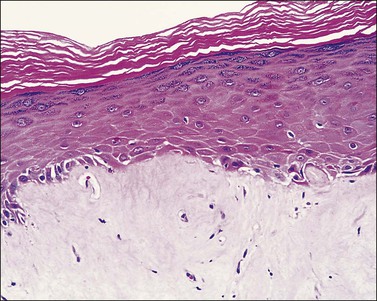

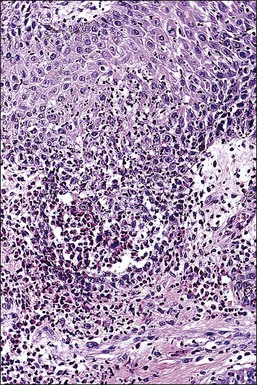

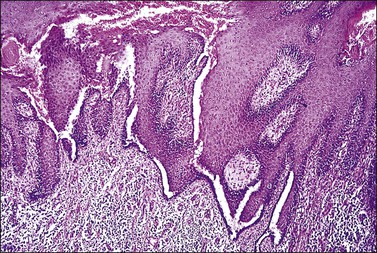

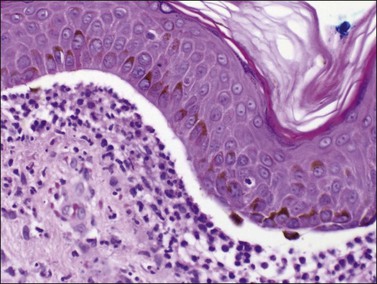

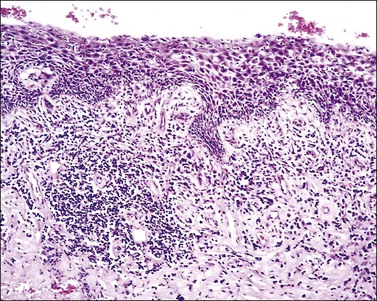

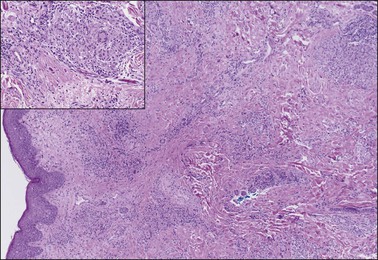

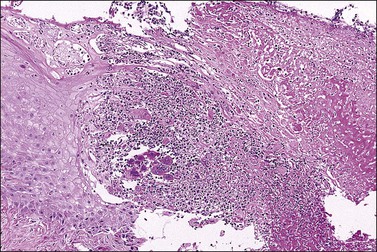

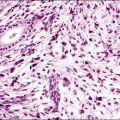

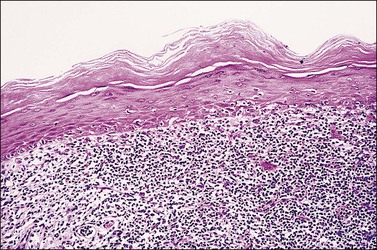

The histopathologic diagnosis of vulvar lichen planus is often difficult. First, mucous membrane lesions may differ considerably from those occurring on vulvar skin. Second, lichen simplex chronicus frequently coexists, and sometimes there is also associated lichen sclerosus. Finally, the erosive pattern, where the epithelium is lost, may be extremely difficult to diagnose due to sampling problems, secondary infection, and inflammation from topical applications. In the skin, two typical microscopic features help in the histologic diagnosis: a band-like chronic inflammatory infiltrate that is predominantly lymphocytic, with rare plasma cells. The inflammation typically involves the upper dermis and immediate overlying epidermis; and liquefaction necrosis of the basal epithelial cells. These cells appear admixed with chronic inflammatory cells, and degenerated keratinocytes result in the formation of colloid bodies (Civatte bodies) (Figures 3.13 and 3.14).

Figure 3.13 Lichen planus. The epidermis shows hyperkeratosis, extensive basal layer destruction, and a dense lichenoid infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction. In the vulva, the histologic changes are not always as florid and classic as shown here.

Figure 3.14 Lichen planus. In the vulva, lichen planus changes may be very focal and show superimposed lichen simplex chronicus due to repeated scratching.

The fully developed epidermal changes usually seen in classic cutaneous lichen planus (saw-tooth pattern, hypergranulosis, orthokeratosis, etc.) are rarely present in vulvar lesions. Accurate diagnosis is important since the erosive form may require immunosuppressive therapy. Also, the presence of chronic lichen planus in the vulva is a risk factor for squamous cell carcinoma.35,57,58 The differential diagnosis includes lichenoid drug reactions, which should be suspected if eosinophils are present.

Immunofluorescent studies often reveal fibrin deposition at the dermal–epidermal junction and, occasionally, granular IgM; rarely, C3 and IgG deposits are also present. The clusters of necrotic keratinocytes (colloid bodies) are positive for IgM in up to 87% of cases and, sometimes, C3 and IgG deposits may be helpful for the diagnosis.59

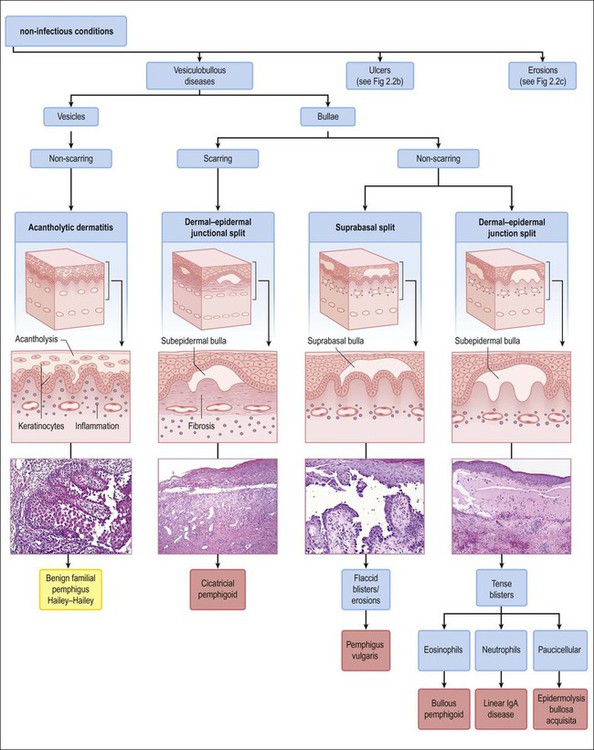

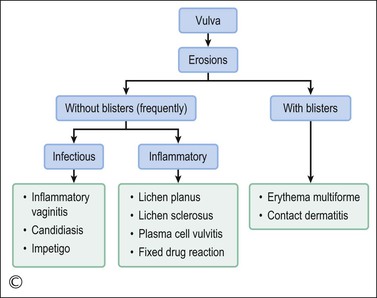

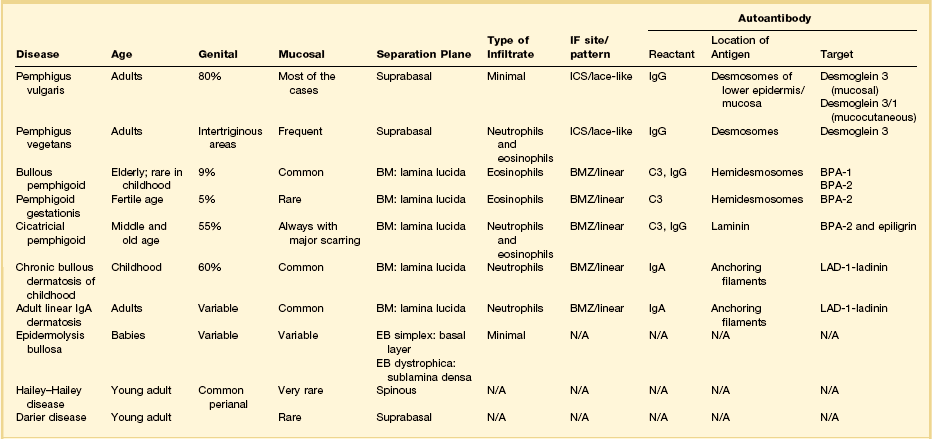

Bullous Disorders

The vesiculobullous disorders result from the congenital or acquired formation of antibodies against components involved in the adhesion of keratinocytes.60 Many of the blistering diseases that affect the skin also involve mucosal sites.61 In the vulva, friction and trauma foster the development of the blistering disorders, which typically present clinically as soggy, weeping, or erosive to ulcerative lesions. Clinical suspicion needs to be high in patients with erosions. Besides a detailed clinical history and careful physical examination, biopsies of the lesion for light microscopy plus perilesional skin for direct immunofluorescence are important. The most significant primary bullous skin diseases affecting the vulva are the following (Table 3.4):

Table 3.4

Pemphigus Vulgaris

Pemphigus vulgaris is an acquired, autoimmune blistering disease representing 80% of all pemphigus cases.15 Autoantibodies develop against the desmosomal protein, desmoglein 3, at intercellular sites between keratinocytes, leading to acantholytic blisters that break easily and form erosions.62,63

Clinical Features

Most patients have oral blisters that precede cutaneous involvement by weeks to months. The vulvar lesions consist of erythematous, moist, eroded plaques, at the edge of which intact blisters may briefly be seen. The classical skin lesions consist of flaccid blisters on a normal or erythematous base. The blisters break easily leading to eroded and crusted areas. Trunk, groins, axillae, scalp, and face are frequently involved. These lesions extend if pressure is applied to the top of the bullae (positive Asboe-Hansen sign). They heal without scarring. The disease activity can be followed by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) titers of circulating antibody to desmoglein 3. The principal cause of death is infection secondary to corticosteroid treatment. The mortality rate is 5–15%. There are reported cases of cervical and vulvar microinvasive squamous cell carcinoma in association with pemphigus vulgaris.64

Microscopic Features

The squamous epithelium shows a suprabasal bulla with scattered neutrophils and eosinophils. Because the disease targets an adhesion protein joining keratinocytes, but not between keratinocytes and basement membrane, the basal keratinocytes remain attached to the dermis, imparting a ‘tombstone appearance.’ Dermal changes are nonspecific. Unfortunately, the separated upper layers of the epidermis frequently fall off during the biopsy process and all that remains is the dermis with the single layer of intact basal keratinocytes. Thus, a useful histologic clue is the presence of clefts extending deep into adnexal structures. A biopsy that includes the edge of the blister increases the chances of finding some surviving acantholytic keratinocytes. Direct immunofluorescence usually shows IgG, especially IgG1 and IgG4, in the intercellular spaces (Table 3.4).59

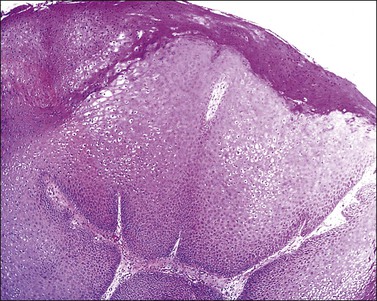

Pemphigus Vegetans

Clinical Features

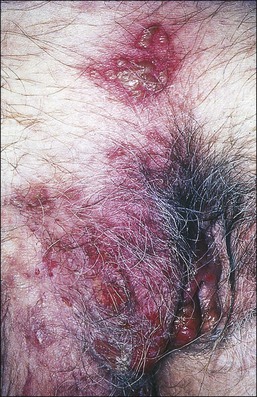

This rare variant of pemphigus shows well-demarcated, warty erythematous plaques with a moist, ulcerated surface that preferentially involves the pubic, perineal, and perianal areas (Figure 3.15). Rarely, blisters are found at the edges of the plaque. As with pemphigus vulgaris, oral lesions are invariably present, and frequently the presenting feature. ‘Vegetans’ alludes to the warty appearance of these lesions that may mislead the clinician to diagnose condyloma acuminatum or even squamous cell carcinoma.

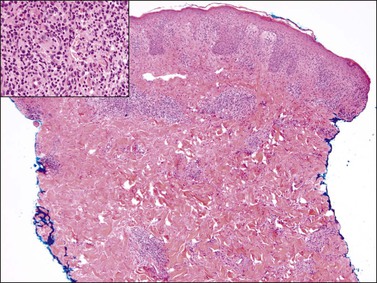

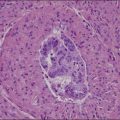

Microscopic Features

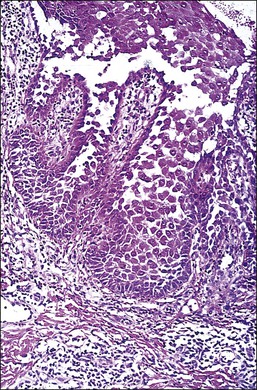

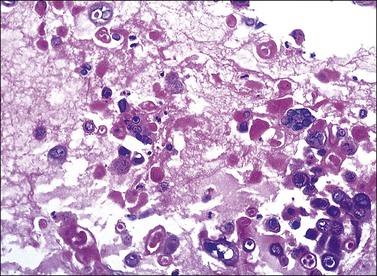

The microscopic as well as immunofluorescent and immunologic findings are similar to pemphigus vulgaris except for the presence of intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses (Figure 3.16) and marked epidermal hyperplasia. The presence of eosinophils and the localized and self-limited character of the disease distinguish it from pemphigus vulgaris. The extreme acanthosis may even suggest squamous cell carcinoma (Figure 3.17). Circulating antibodies of the IgG2 and IgG4 subclasses, with strong complement fixation, are commonly present in pemphigus vegetans (Table 3.4).

Bullous Pemphigoid and Cicatricial Pemphigoid

Bullous pemphigoid is a chronic, subepidermal, acquired, autoimmune blistering disease.65–69 Multiple, tense blisters typically occur on erythematous plaques or normal skin in elderly patients. These patients develop autoantibodies that target basal cells’ basement membrane attachment plaque (hemidesmosome).61 Cicatricial pemphigoid or benign mucous membrane pemphigoid is a chronic bullous disease that affects predominantly oral and ocular membranes and results in scarring and stenosis.70,71 Anogenital region involvement occurs in 20% of patients. Both bullous and cicatricial pemphigoid can be the result of a drug hypersensitivity reaction. Severe cicatrization with shrinkage may suggest lichen sclerosus or lichen planus;72 however, in contrast to lichen sclerosus or lichen planus, cicatricial pemphigoid is associated with small blisters and a positive Nikolsky sign, i.e., formation of blisters in unaffected tissue by application of light pressure.70,71

Microscopically, there are subepidermal blisters and a mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate within the dermis. Eosinophils are numerous. In cicatricial pemphigoid the lesions evolve to scars. Perilesional direct immunofluorescence usually shows a linear band of IgG with or without C3 at the dermoepidermal junction (Table 3.4). IgA is found in 20% of cases. Systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressive drugs may be helpful.

Chronic Bullous Dermatosis of Childhood and Adult Linear IgA Bullous Dermatosis

This is an immunobullous disorder of unknown etiology in which linear deposits of IgA are detected in subepidermal blisters. There are two clinical variants that are commonly regarded as different expressions of the same entity. One is the chronic bullous dermatosis of childhood and the other is the adult linear IgA bullous dermatosis. In the first years of life, chronic bullous dermatosis presents with the abrupt onset of large, tense bullae or ‘cluster of jewels’ that have a propensity for perioral and perigenital areas, but extend to thighs and lower abdomen. Initially the blisters fill with clear fluid, but secondary infection results in pustules (Figure 3.18). Commonly, this disease resolves in several months. In adults, the clinical presentation is protean and mimics other bullous disorders. Amiodarone, vancomycin, lithium, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can induce this immunobullous disorder.

Figure 3.18 Chronic bullous disease of childhood. The disease presents with groups of itchy blisters and erosions. The genital region is often involved.

Histologically, there are subepidermal blisters with neutrophilic microabscesses in the papillary dermis, a finding indistinguishable from that seen in dermatitis herpetiformis. Fibrin with leukocytoclasis in the tip of the papilla favors dermatitis herpetiformis, while the presence of neutrophils parallel to the dermal–epidermal junction points toward linear IgA dermatosis (Figure 3.19). However, only immunofluorescence definitively separates these two diseases. Bullous pemphigoid is distinguished from IgA dermatosis by the linear IgG basement membrane deposits (Table 3.4).

Inherited Dermatoses

Hailey–Hailey Disease

Hailey–Hailey disease is an acantholytic dermatosis involving flexural areas that usually starts in the late teens.73,74 It is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait and the responsible gene called ATP2CL is mapped to chromosome 3q21–q24. Patients suffer from recurrent clusters of vesicles that evolve into bullae that rupture, leaving crusted, erythematous erosions (Figure 3.20). The disease, when occurring in the perineal region, frequently extends to the vulva. Unusual cases are restricted to the vulva.75,76 Some may spread to involve the vagina.77

Figure 3.20 Hailey–Hailey disease. This dyskeratotic genodermatosis presented with irritable superficially eroded plaques in flexural sites.

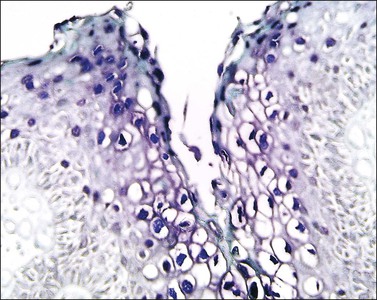

Microscopically, early lesions show suprabasal clefting. Acantholytic cells may border the cleft or lie free in the cavity. With time the acantholysis involves the entire epidermis, producing the characteristic image of a ‘crumbling, dilapidated brick wall’ (Figure 3.21). The acantholysis is more marked than in Darier disease. The broad lesion and degree of inflammation help to distinguish Hailey–Hailey disease from other acantholytic dermatoses. Immunofluorescence tests in difficult cases help separate it from pemphigus vulgaris (Table 3.4). Isolated cases of squamous cell carcinoma have arisen on a background of Hailey–Hailey.78,79

Darier Disease (Keratosis Follicularis)

Darier disease is a chronic acantholytic dermatosis inherited as an autosomal dominant disorder involving the ATP2A2 gene located on chromosome 12q23–24.1.80 It usually appears in adolescence with yellow to brown, crusted papules that affect the seborrheic areas and frequently involves the vulva.81–83 Darier disease has a predisposition to bacterial, fungal, and viral infections. Follow-up of these patients is recommended due to the rare cases of squamous cell carcinoma associated with this disease.84

Microscopically, the keratotic papules disclose acantholysis that involves rete ridges in which a cleft or lacuna forms (Figure 3.22). The papillary dermis typically protrudes into the lacuna, which is lined by a single layer of basal cells (forming so-called ‘villi’). Overlying these changes is a thick area of orthokeratosis with focal parakeratosis. Accompanying these features are dyskeratotic cells in the form of ‘corp ronds’ and ‘grains.’ Differential diagnosis includes Hailey–Hailey disease, localized acantholytic disease of the vulva, and warty dyskeratoma. Corps ronds are cells located in the upper malpighian layer and stratum corneum with a small pyknotic nucleus, clear perinuclear halo, and bright eosinophilic cytoplasm. The dense and bright peripheral rim of cytoplasm represents aggregates of tonofilaments and keratohyaline granules. Grains are small cells with elongated nuclei and a small amount of cytoplasm; electron microscopy demonstrates premature aggregation of tonofilaments. The synthesis of keratohyaline in association with clumped tonofilaments demonstrated by electron microscopy is distinctive of Darier disease and can separate it from Hailey–Hailey disease (Table 3.4).

Other Inflammatory Diseases Affecting the Vulva

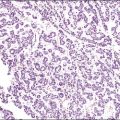

Plasma Cell Vulvitis (Vulvitis of Zoon)

A chronic inflammatory disorder of unknown etiology, Zoon vulvitis exhibits extensive plasma cells in the mucosa.85–88 Patients after middle age present with a solitary, sore, orange-red glistening 1–3 cm lesion on the vestibular mucosa (Figure 3.23).89,90 On microscopic examination there is a dense and band-like mucosal infiltrate of plasma cells admixed with lymphocytes (Figure 3.24).91 The epidermis eventually becomes atrophic, with loss of the surface keratin and of the stratum granulosum. The stratum spinosum frequently exhibits flattened, lozenge-shaped keratinocytes separated by mild spongiosis. The basal layer is often irregular and may exhibit exocytosis of lymphocytes. The dermis shows increased numbers of dilated, thin-walled vessels, often with red cell extravasation. Immunohistochemistry for light chain restriction helps exclude plasmacytoma if suspected. The lesions resolve slowly, leaving behind a rusty stain from resolved microhemorrhages. Recurrences are common.

Erythema Multiforme and Stevens–Johnson Syndrome

This disease presents at any age and the skin lesions appear targetoid (central zone of necrosis, blister, or erosion surrounded by erythema and edema) most frequently affecting the extremities in a symmetrical distribution. In the genital region, it usually presents as a bullous eruption.92 On microscopic examination, scattered apoptotic keratinocytes are present in the epithelium, often associated with intraepithelial vesicle formation, upper dermal edema, and a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Erythema multiforme and Stevens-Johnson syndrome share identical histologic presentation. Erythema multiforme is a clinical diagnosis that usually rests on the clinical history and appearance, and the presence of other lesions outside the vulva. Most episodes are recurrent, lasting on average 2 weeks without sequelae.

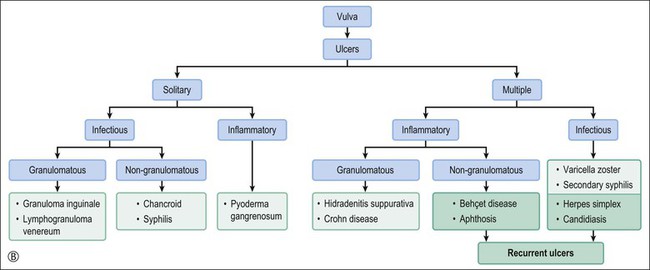

Behçet Disease

Behçet disease is defined by the triad of recurrent oral ulcers, genital ulcers, and ocular inflammation.93,94 The pathogenesis is unknown. Behçet disease can cause deep ulcerations in the vulva that may lead to labial fenestration and gangrene.95,96 Aphthous (small ulcers) stomatitis is the initial manifestation in two-thirds of patients.97 Genital and perianal aphthae are in general larger, deeper, and more painful than oral lesions (Figure 3.25). The histologic features are usually nonspecific, and clinical–pathologic correlation is necessary for diagnosis. Although necrotizing arteritis is frequent and can be considered a cardinal pathologic finding, in the presence of ulceration, it is difficult to determine whether it is primary or secondary. The dermis often contains a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Endothelial cell swelling also occurs and may result in venous thrombosis. Other manifestations in the skin include erythema nodosum-like lesions. Unlike erythema nodosum, this entity lacks histiocytic granulomas.

Crohn Disease

Crohn disease is a granulomatous inflammation, most commonly involving the small bowel, but occasionally the vulva and the perineum in adults and children.98–101 In fact, genital Crohn disease is more frequent in children than in adults.102 The cutaneous changes can both precede the gastrointestinal involvement and lack any correlation in severity between cutaneous and gastrointestinal manifestations. Extraintestinal findings precede the gastrointestinal involvement in one-fourth of cases. The clinical appearance of vulvar Crohn disease is variable. When associated with local colonic disease, perineal ulcers and large, edematous skin tags are characteristic.100 Sometimes fistulas extend from the affected bowel into perineal and even vulvar skin or Bartholin glands, resulting in indurated, tender, inflamed areas that drain pus. The latter may mimic bartholinitis.103 Vulvar Crohn disease may occur as erythematous plaques on the labia majora (Figure 3.26) and pubic skin. Occasionally, it may present as chronic sloughing ulcers on the mucosal surfaces of the labia. The pathologic changes include massive dermal and subcutaneous edema, and markedly dilated lymphatics. Noncaseating sarcoidal granulomas are diagnostic (Figure 3.27), but often ill-formed aggregates of histiocytes with variable numbers of lymphocytes are seen instead. Ulcerated or fistulous lesions often show a predominance of secondary features such as fibrosis, chronic inflammation, suppuration, and granulation tissue.

Hidradenitis Suppurativa

Hidradenitis suppurativa is chronic folliculitis of apocrine gland-bearing skin, affecting particularly the axilla and vulva. The etiology is unknown. Patients usually present with recurrent painful subcutaneous abscesses, followed by sinuses from which foul pus may drain (Figure 3.28).104 Suppuration results from secondary infection by a wide range of bacteria, including anaerobes. Squamous cell carcinoma is a rare complication, and has been reported in long-standing lesions.105

Vulvar Pain Syndromes

Vulvar Vestibulitis

Clinical Features

The vulvar vestibule is the ring of epithelium proximal to Hart’s line (see glossaries at the end of this chapter), which is in continuity with the hymen and contains the minor vestibular glands and the openings of the ducts of Bartholin and Skene glands. Vestibulitis is a complex of introital dyspareunia and severe tenderness on light pressure.106–109 Most women present in their twenties and thirties with dyspareunia. Some patients give a history of severe Candida infection or a gynecologic procedure. Examination may show punctate erythema and these areas are likely to be biopsied. The vulva is otherwise normal. Vestibulitis is more common in women with migraine, irritable bowel syndrome, and/or myalgic encephalopathy syndrome.110 Treatment with low-dose tricyclic antidepressant drugs often brings at least some relief.

Vestibulitis is rarely biopsied, and the histologic changes are nonspecific, subtle, and of dubious significance. Biopsies may show peripheral nerve hyperplasia in the vestibule, without significant inflammation.111 A sparse lymphocytic infiltrate may surround the necks of the minor vestibular glands.

Dysesthetic Vulvodynia

Clinically, a severe burning sensation affects the entire vulva, often extending onto the perineal skin, upper thighs, and abdominal wall.113–115 Dysesthetic vulvodynia tends to affect older women with a history of lumbar disc disease, constipation, or previous gynecologic surgery. Physical examination reveals only vulvar atrophic change, without tenderness to palpation. There may be altered sensitivity to light touch over the lower abdomen, pubis, and thighs. A thorough neurologic examination is required to exclude cauda equina lesions or neuralgia of the pudendal nerve. Treatment with low-dose tricyclic antidepressants is often successful.112

Pigmentary Alterations

Hyperpigmentation

Increased pigmentation in the vulvar skin may be due to increased:

• Melanin deposition in the epidermis or dermis

• Thickness of the keratin layer in a verruciform or papillomatous pattern

Hyperpigmentation Due to Melanin in Vulvar Skin

The pigmented melanocytic nevi and melanoma are described in Chapter 5.

Idiopathic Acquired Pigmentation (of Laugier)/Vulvar Melanosis.

Marked, macular hyperpigmentation appears on the vulva, vagina, and cervix, without a preceding history of trauma or inflammation.116,117 Lesions can reach several centimeters in diameter. Areas are often multiple (Figure 3.29). The etiology is unknown. Lesions show increased melanin deposition in the basal layer of keratinocytes and dermal melanophages are invariably present.118 The Masson–Fontana stain serves to emphasize the increased melanin. Immunocytochemical stains show a normal or mildly increased number of melanocytes in the pigmented area. Lesions with melanocytic hyperplasia are best termed lentigines.

Hyperpigmentation Due to Increased Keratin in Stratum Corneum

Acanthosis Nigricans.

• Multiple endocrine disorders and congenital syndromes sharing resistance to insulin and hyperinsulinemia.119 The effect of high insulin levels on insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) receptors on keratinocytes is believed to produce the skin changes. Stimulation of the same receptor on ovarian stromal cells can lead to stromal hyperthecosis and hyperandrogenism.

• Rare familial acanthosis nigricans is inherited as an autosomal dominant condition and is not linked to insulin resistance. These rare syndromes include: Lelis’ syndrome or acanthosis nigricans with ectodermal dysplasia, severe achondroplasia with developmental delay and acanthosis nigricans (SADDAN syndrome), and Crouzon syndrome with acanthosis nigricans.120,121 The molecular basis of these syndromes is mutations in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) gene on chromosome 4p16.3.122

• Drug-induced forms occasionally occur with various agents including oral contraceptives, nicotinic acid, and the folate acid antagonist triazinate.

• Paraneoplastic type or malignancy-associated acanthosis nigricans is a rare disorder usually seen with adenocarcinoma of the stomach or some other part of the gastrointestinal tract.123 Usually the acanthosis nigricans and the neoplasm are diagnosed simultaneously. Sometimes, the cutaneous manifestation precedes or follows the tumor. Epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor (TGF-α) are potential factors produced by these tumors and can lead to the abnormal proliferation found in acanthosis nigricans.

Microscopically, the skin lesions show papillomatosis with upwardly projected dermal papillae covered by thinned epidermis. Between the projections, the epidermis shows mild acanthosis with hyperkeratosis. The basal layer is mildly hyperpigmented. Sometimes, mucosal lesions show marked acanthosis and mild chronic inflammation in the submucosa. These lesions can be confused with condyloma acuminatum.

Hypopigmentation

Vitiligo

Vitiligo is an inherited leukoderma in which melanocytes are destroyed in the involved areas. It is usually symmetrical and often involves the perineum. Onset occurs at any age, but half appear before the age of 20 years. The presence of antimelanocyte antibodies supports the immune theory as an effector of melanocytic destruction.124 Melanocytes sometimes remains in the hair follicles, and it is from the follicular melanocytes that the repigmentation occurs. In cases of depigmentation, it may be difficult to differentiate vitiligo from lichen sclerosus. Both are in the same group of inherited autoimmune disorders and sometimes coexist in the same patient. However, vitiligo is a purely macular lesion, lacking the atrophy or sclerosis of lichen sclerosus. Vulvar skin affected by end-stage vitiligo is completely devoid of melanin within the basal keratinocytes, and melanocytes are entirely absent in the basal layer. The ideal biopsy is taken through the edge of a lesion so that the vitiligo patch can be compared with adjacent normal skin. The edge of the vitiligo lesion may show a narrow zone of degenerating basal melanocytes and a lymphocytic infiltrate in underlying papillary dermis and lower epidermis. The Masson–Fontana stain for melanin and immunohistochemical stains (Melan A and HMB-45) for melanocytes help highlight the differences between the lesion and adjacent normal skin.

Drugs

Fixed Drug Eruptions (Dermatitis Medicamentosa)

Fixed drug eruption is an infrequent, but recurrent reaction that occurs each time an individual is exposed to a triggering drug. The classic presentation is that of a single, well-defined, erythematous, round to oval plaque with a dusky center and possible bulla formation leading to erosion. This lesion develops 1–2 weeks after a first exposure. This period is reduced to 24 h in subsequent exposures. More than 100 drugs are known triggering agents, and the most frequent are sulfonamides, tetracyclines, tranquilizers, quinine, phenolphthalein (formerly used in laxatives), and analgesics. The current hypothesis concerning the pathogenesis of fixed drug eruptions is that the eruptions causative drug activates keratinocytes to release cytokines or induces keratinocytes to express surface adhesion molecules, leading to activation of epidermal CD8+ T-cells, and subsequent death of keratinocytes by FasL-mediated pathway.125

The most common histopathologic findings of fixed drug eruption show a lichenoid inflammatory reaction with basal layer vacuolization and Civatte bodies associated with a heavy, superficial and deep dermal lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 3.30). The infiltrate sometimes contains a few neutrophils and eosinophils. Damage to the epidermal basal layer leads to release of melanin, which macrophages in the upper dermis capture. While these findings resemble that of erythema multiforme, fixed drug eruption also shows the presence of a mid to deep dermal inflammatory reaction, neutrophils, and prominent melanin incontinence. Histologic findings in drug eruption are usually nonspecific and are only suggestive or supportive of a drug eruption. Patch testing, indirect and direct Coombs tests, other specific laboratory testing, as well as a detailed clinical history, are necessary to precisely diagnose such cases.

Vulvar Infections and Infestations

Vaginal infections may cause vulvar symptoms either by extension or by the irritant effects of vaginal discharge. These disorders will be discussed in Chapter 7.

Bacterial Infections

Streptococcal Infections (Necrotizing Fasciitis)

Microscopically, extensive necrosis extends from the epidermis, to subcutaneous tissue, to fascia, and sometimes to muscle. Numerous polymorphonuclear leukocytes and mononuclear cells infiltrate the tissue and necrotizing vasculitis with thrombi is apparent. Large numbers of bacterial colonies pervade the upper dermis. Necrotizing fasciitis is often regarded as a form of septic vasculitis.126

Syphilis

Clinical Features

Syphilis is a chronic, worldwide, sexually transmitted disease caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. Coinfection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is well recognized. Acquired syphilis is divided into four stages (primary, secondary, latent, and tertiary) with distinct clinical presentations separated by asymptomatic periods. The primary or initial lesion is the chancre, an indurated, painless, shallow ulcer with well-defined borders that appears within 3–4 weeks at the site of inoculation. Multiple lesions occur, especially in immunocompromised patients. The serum exudate from the chancre contains numerous spirochetes, which can be identified by dark-field microscopy, permitting prompt diagnosis. The primary site in women is often on the vulva or perineum; other sites include the cervix, urethra, lip, or tonsillar fossae. The lesion is self-healing within 1–5 weeks leaving a small discrete stellate scar. Regional painless lymphadenopathy presents 3–4 days after the chancre.

Between 4 and 8 weeks after the chancre, untreated patients develop constitutional symptoms and mucocutaneous lesions as part of secondary syphilis. Fever, lymphadenitis, and hepatitis occur in association with an erythematous exanthem of the trunk, genital area, flexor aspect of limbs, and, characteristically, the palms and soles. Atypical presentations may occur in patients with concurrent HIV infection. Pregnant women can infect the fetus via transplacental passage of the spirochete. Some cases of secondary syphilis show large, flat, fleshy, moist papules or condylomata lata in the labia and perineum. Condylomata lata are among the most infectious lesions in syphilis; dark-field examination shows numerous treponemes. Such lesions also occur on other mucocutaneous borders. After 3–8 weeks lesions disappear spontaneously. Diagnostic tools in secondary stage include serologic tests that measure antibodies to cardiolipin by rapid plasma reagin (RPR) and venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) assay. In the setting of HIV infection or immunosuppression, one must be aware of false-negative RPR results or the prozone effect. It occurs when the antibody titers in the infected individual are so high that the visualization of the reaction is impaired.127 Other methods detect antibodies to surface proteins of T. pallidum by T. pallidum hemabsorption test (TPHA) or microhemagglutination assay for antibodies to T. pallidum (MHA-TP). Latency, the period between healing of the clinical lesions and appearance of late manifestations, can last for many years. The gumma, the classic lesion of tertiary syphilis, is rarely seen on the vulva.

Microscopic Features

Dieterle, Warthin–Starry, or Steiner stains may demonstrate the spirochetes, but, today, antibodies against T. pallidum are available for formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue and represent a more specific and sensitive method (Figure 3.31).128 In primary syphilis spirochetes are usually identified at the dermal–epidermal junction and within and around superficial dermal blood vessels.

The histologic findings of secondary syphilis vary. The epidermal changes range from normal to hyperplastic with spongiosis. There are variable degrees of plasmacytic infiltrate and vascular endothelial swelling. The perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate usually involves the superficial and deep vascular plexus. Plasma cells are less prominent in macular lesions (Figure 3.32). The lymphocytic infiltrate can be so exuberant as to simulate lymphoma, but its mixed nature would be rare in such a neoplasm. Early lesions exhibit a neutrophilic vascular reaction with occasional microabscesses. In late syphilitic lesions granulomas of the palisading type may simulate granuloma annulare or less frequently sarcoidal type granulomas. Although secondary syphilis occasionally mimics other skin diseases the predominance of plasma cells in the infiltrate is a valuable hint. Condylomata lata have epidermal hyperplasia with hyperkeratosis and patchy parakeratosis. The latter is associated with a superficial and mid-dermal perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate.

Gonorrhea

Neisseria gonorrhoeae is a Gram-negative diplococcus. Infection primarily affects the urethra but may spread to the vagina and cervix.129 The paraurethral and Bartholin glands may be infected and, in the latter, an acute abscess may ensue. Gonococcal vulvitis is rare in adult women but is a common feature of infection in prepubertal children. Microbiologic culture is important diagnostically. Primary lesions are often ulcerated with underlying dense dermal neutrophilic infiltrate with abscess formation. Gram-negative intracellular diplococci can be seen.

Chlamydial Infection (Lymphogranuloma Venereum)

Chlamydia trachomatis (serotypes L1, L2, and L3) is the obligatory intracellular microorganism responsible for the sexually transmitted lymphogranuloma venereum. This infection is prevalent in tropical climates and women are commonly asymptomatic carriers. The initial lesion is a small, painless papule or vesicle that frequently erodes, healing within several days without residual scar. Subsequently, the infection spreads via the lymphatics and manifests as enlarged painful inguinal and/or femoral lymph nodes. The lymph nodes can evolve to bubo formation leading to spontaneous rupture and sinus tract formation. Without treatment, extensive necrosis and scarring result in lymphedema, which can evolve to elephantiasis of the genitalia. Lymph nodes are occasionally excised for histologic diagnosis and show serpiginous or stellate abscesses with necrotic tissue and neutrophils surrounded by a macrophage and giant-cell granulomatous reaction (‘suppurating granulomas’). Only one-third of cases reveal positive cultures. Therefore, the main diagnostic tools are serologic; however, they do not distinguish the different serotypes. A complement fixation titer of more than 1 : 64 in concert with the clinical findings previously described are diagnostic of lymphogranuloma venereum. A microimmunofluorescence test can detect antichlamydial antibodies to different serologic variants of C. trachomatis as well as various PCR-based tests.130 Treatment is with systemic tetracycline or doxycycline.

Fungal Infections

Candidiasis

Clinical Features

Candidiasis is one of the most frequent infections of the genital and anal region.131,132 Candida albicans, the most frequent Candida species involved in human infection, is a normal inhabitant of the gastrointestinal tract and is found in the mouth of approximately half of normal individuals. Pregnancy, immunologic and endocrine dysfunction, immunosuppression, high-dose estrogen, antibiotic or systemic corticosteroid therapy, and debilitating states all predispose to clinical infection. Vulvovaginal candidiasis presents with vaginal and vulvar itching and burning, accompanied by vaginal discharge. Women of childbearing years are predominantly affected. A characteristic white curd (Candida comes from the Latin candidus or dazzling white) appears on the vagina walls. Erythema, edema, and fissuring of the vulva may occur. Diagnosis is confirmed on culture of a high vaginal swab or by finding hyphae and spores on a Gram-stained film from the vaginal discharge. C. albicans is the culprit in most cases, but other Candida species such as C. glabrata and C. tropicalis are responsible in a minority and can be more resistant to conventional treatments.

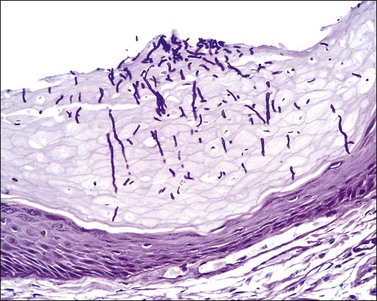

Microscopic Features

The diagnosis of vulvar candidiasis is usually evident once a special stain for fungi is used (Figure 3.33). The presence of parakeratosis with neutrophils that appears disproportionate to the degree of spongiosis should direct the pathologist to request a stain for fungi (PAS or GMS).

Pityriasis Versicolor

Pityriasis versicolor or tinea versicolor is a common, noncontagious, superficial fungal infection. Malassezia globosa in its mycelial phase is the causative agent. It occasionally involves the labia majora, producing hypopigmented or hyperpigmented patches. Hyperpigmentation may result from large melanosomes, vascular erythema, or orthokeratosis, while hypopigmentation is due to azelaic acid, a tyrosinase inhibitor the organisms produce. Examination with a Wood’s lamp accentuates the lesion, producing a dull green fluorescence. These findings differentiate this infection from erythrasma, a Corynebacterium minutissimum infection producing a bright, coral-red fluorescence under a Wood’s light. The characteristic histologic finding of ‘spaghetti and meatballs’ is the presence in the stratum corneum of numerous round budding yeasts (blastoconidia) and short septate hyphae (pseudomycelia)

Viral Infections

Herpes Virus Infection

Clinical Features

Herpes simplex viruses (HSVs), ubiquitous type 1 and type 2 DNA viruses, produce primary infection, latency, and recurrent orolabial and genital disease.133,134 Genital herpes, the most frequent sexually transmitted disease worldwide, is generally associated with HSV type 2 (70–90%) with a recent increase being noted for type 1 (10–30%).135,136 In the last two decades, the seroprevalence of HSV type 2 has increased in the United States by 30%, or with one million new primary genital infections yearly. The virus replicates at the site of infection, then travels to the dorsal root ganglia through retrograde axonal flow and remains in a latent phase, with recurrent reactivations occurring spontaneously or following stimuli such as fever, stress, ultraviolet radiation, or immunosuppression.

The first episode of primary infection occurs 3–7 days after exposure, with a prodrome of general malaise associated with nonspecific genital findings. In time, the classic lesions develop, which are vesicles on an erythematous base arranged in clusters that evolve to pustules and/or erosions (Figure 3.34). These lesions are excruciatingly painful. Accompanying regional lymphadenopathy may last for more than a week. The vesicles heal without scarring unless there is secondary infection. Recurrent genital infection is in general milder and even subclinical.

Microscopic Features

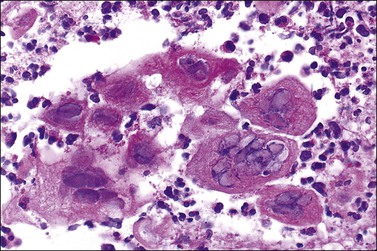

The earliest changes appear in the nucleus of infected keratinocytes, with peripheral clumping of chromatin, homogeneous ‘ground-glass’ appearance, and ballooning. These early changes start at the basal layer. However, most biopsies include an intraepidermal vesicle resulting from infected cell swelling and losing attachment (ballooning degeneration), and progressive hydropic swelling of cells transforming in large and clear keratinocytes (reticular degeneration) (Figure 3.35). Ballooning changes are specific for viral infection and the cells can be multinucleated, with eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions and/or dense eosinophilic cytoplasm. Ulceration occurs, at the edges of which large, infected keratinocytes with intranuclear inclusions or multinucleated cells are often usually easily identified (Figures 3.36 and 3.37). In the late stages ghost cells remain, which are infected keratinocytes where the intranuclear inclusions have turned from eosinophilic to a slate gray color. Perivascular lymphocytic and neutrophilic inflammation is seen in the upper dermis. Follicles are more often involved in recurrent lesions. If the latter is the predominant finding, the diagnosis of herpes folliculitis can be rendered. Other adnexal structures can be affected, as in herpes syringitis. Eccrine ducts and glands show changes of the viral infection. The nerves in the biopsy specimen can show inflammation, Schwann cell hypertrophy, and viral cytopathic changes demonstrating that nerves are not only a conduit for this virus but also a target of infection. Acyclovir may reduce the severity of infection if given early in the course of illness.

Figure 3.35 Herpes simplex infection. There is extensive destruction of the epidermis at the edge of a blister. The reticular degeneration pattern of epidermal destruction is characteristic of acute herpes/varicella infections of skin but can also be seen in the Stevens–Johnson variant of erythema multiforme.

Varicella Zoster Virus Infection (Vulvar Shingles)

Varicella zoster virus is the etiology of both varicella (chicken pox) and herpes zoster (shingles). Ninety percent of children in the United States under the age of 10 years have suffered varicella. Subsequently, the virus can remain latent in nerve ganglia until it is reactivated in 20% of immunocompetent hosts and half of immunosuppressed individuals. Herpes zoster is usually a disease of patients over 50 years. The incidence is increasing in immunocompromised patients, especially those infected with HIV. In most patients herpes zoster starts with a prodrome of pain, pruritus, tingling, or tenderness in a dermatomal distribution. A painful eruption of clustered papules follows, and in a short period of time, the papules transform to vesicles on an erythematous base (Figures 3.38). In the genital area erosions predominate. The distribution of the rash is a strong diagnostic clue. Confirmation comes from direct fluorescence antibodies or PCR viral detection. Microscopically, the changes overlap with those seen in herpes simplex infections (Figure 3.39). Immunoperoxidase stains can be useful in separating herpes simplex from varicella zoster.

Other Virus Infections

Molluscum Contagiosum

Clinical Features

Molluscum contagiosum is a poxvirus infection exhibiting single or multiple, 2–8 mm dome-shaped papules with a central umbilicated core of white material. This infection predominantly affects children and adolescents. Commonly, spontaneous regression occurs. In adults, molluscum contagiosum occurs principally as a sexually transmitted disease involving the vulvar and perianal regions. Primary or recurrent molluscum contagiosum often complicates HIV disease.

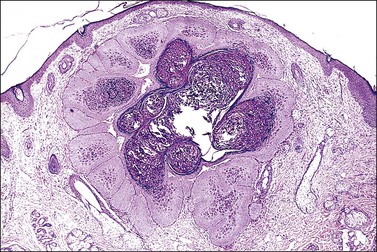

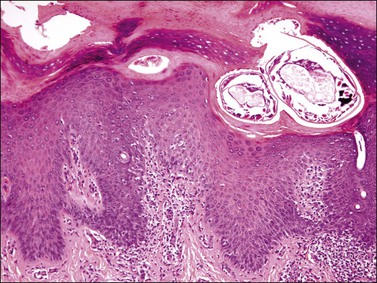

The histologic features of molluscum contagiosum are pathognomonic. An endophytic growth of squamous epithelium arranged as lobules is seen in low power. Eosinophilic inclusion bodies fill the cytoplasm of infected cells above the basal layer. The inclusions can acquire large dimensions and compress the nucleus of the infected keratinocytes to the periphery (Figures 3.40 and 3.41). In a fully evolved lesion, the epidermis ruptures under the pressure of the underlying proliferation almost entirely occupied by viral inclusion, and produces the characteristic small white core. The viral inclusion bodies become more basophilic as they enlarge.

Human Papillomavirus Infections

Clinical Features

Papillomaviruses are a large group exceeding 100 genotypes of DNA viruses that infect skin and mucosae, producing warts, intraepithelial neoplasia, or invasive squamous cell carcinoma.137 Genital HPV is a common, sexually transmitted disease affecting predominantly young adults.138 The vulva, vagina, cervix, and anus are frequent areas of infection. Transmission of this virus can occur from direct contact with individuals who harbor clinical or subclinical HPV lesions. The lesions are in most cases transient, but the virus may recur, persist, or enter a latent phase. Genital warts are by far the most common manifestation and the majority of infections are with HPV types which, in the normal host, carry a low risk of neoplastic change. In immunocompromised patients, HPV infections often persist and increase the risk of developing neoplasms. HPV infections affecting the genital tract can be categorized as follows:

• Those that produce warts on fully keratinized skin, i.e., common and plantar warts.

• Those that cause warts, dysplasia, and squamous cell cancer in the immunosuppressed or in patients with the rare inherited disorder epidermodysplasia verruciformis.

• Those that infect the nasopharyngeal, conjunctival, and anogenital mucosal surfaces. These can be subdivided into low-, intermediate-, and high-risk types for the development of intraepithelial dysplasia and squamous cell cancer.139 As on the cervix, HPV types 16 and 18 are most definitely linked to vulvar and anal intraepithelial neoplasia and squamous cell carcinoma. However, the risk of cancerous change on the vulva and anal mucosa seems much less than on the cervix.

The clinical presentation will depend on the HPV type, the anatomic location, and the host’s immune status. These are the most frequent clinical presentations:

• Condylomata acuminata (singular: condyloma acuminatum) or anogenital warts occur on the nonhair-bearing, partially keratinized skin of the vulva (labia minora), the perineum, perianal region adjacent to the skin/mucosal interface, or in adjacent areas such as inguinal folds and mons pubis. They are discrete, skin-colored to brown, exophytic papillomas. They acquire a whitish surface when macerated in moist areas. The lesions range from several millimeters to being large and broad based, several centimeters in size, and forming confluent plaques that may extend into the vagina, urethra, or anal canal. One-third of these cases recur. Although malignant transformation is infrequent, the chances are higher than with other types of warts. The most frequent oncogenic HPV types are HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, and 35. The most frequent HPV types associated with the benign lesions are HPV 6 and 11 (see Chapter 9).

• Papular and keratotic warts tend to occur on fully keratinized and hair-bearing skin (e.g., labia majora).

PCR has identified HPV DNA in skin with no clearly defined lesions. Dilute acetic acid will turn these abnormal areas white, albeit the acetowhite coloring only reflects thickening of the squamous epithelium and it is not diagnostic of HPV infection (e.g., acetowhite coloring can be seen in Candida infection, psoriasis, lichen planus, or eczema). Detection of this virus has not been only in subclinical lesions but also in normal-appearing skin. Furthermore, the virus is resistant to heat and desiccation. This explains the high recurrence rate of lesions (e.g., 20–50% for genital warts) and supports the consideration that treatment may not prevent transmission of HPV. Genital warts are of concern to the healthcare provider when they occur in prepubertal individuals.

The two major methods for detection of carcinogenic HPV DNA are hybridization with signal amplification and genomic amplification using PCR techniques. Currently, the Food and Drug Administration approved test is the hybridization method, Hybrid Capture 2 (HC2; Qiagen Corporation, Gaithersburg, MD).140 To date HPV DNA detection by PCR-based methods has been used mainly for research.

Microscopic Features

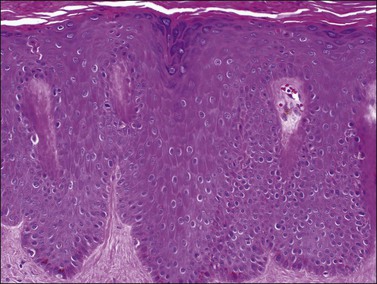

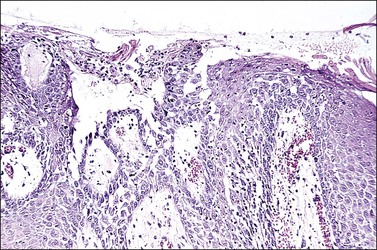

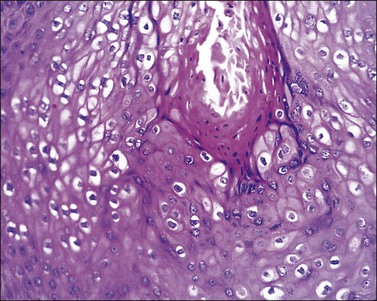

The common wart shows papillomatosis with hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis, the latter especially located in the tips of the papillae. The elongated rete ridges often show an inward orientation at the lesion’s edge (Figure 3.42). Hypergranulosis with large clumps of basophilic keratohyaline material lie in the valley of the papillomatosis. Koilocytes, which are large vacuolated cells with small pyknotic single or multiple nuclei, are located in the superficial malpighian layer. In flat warts koilocytes present as a more or less continuous line in the upper epidermis. Condylomata acuminata show marked epidermal acanthosis with hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis and a minor component of papillomatosis with only a few vacuolated koilocytes in the upper malpighian layers. Papillomatosis is more rounded at the base than in common warts, and koilocytes are less frequently seen than other variants of warts and are usually present beneath the areas of parakeratosis (Figures 3.43 and 3.44). Coarse keratohyaline granules are commonly present. Changes of lichen simplex chronicus may be superimposed due to trauma to the lesion. The histopathologist needs to know whether the warts have been treated before biopsy. Podophyllin paints and gels are still a common treatment and, if applied within 48 hours of biopsy, the squamous cells may show severe nuclear and cytoplasmic atypia and large numbers of mitotic figures due to metaphase arrest. These changes can persist long after treatment has stopped. These changes may be a pitfall in the diagnosis of intraepidermal malignancy.

Figure 3.42 Condyloma acuminatum. Hyperplastic thickening of the epidermis with characteristic HPV koilocytosis of many of the epidermal cells.

Infestations

Scabies

Clinical Features

The female mite, Sarcoptes scabiei var. hominis, infests the epidermis. The primary means of transmission is direct close contact. The female mite lives out her 30 day life cycle in burrows in the epidermis where she lays her eggs, causing an allergic reaction to the mite protein. The first infestation takes 2–6 weeks before the host is sensitized and develops pruritus. The combination of severe nocturnal itching with the finding of papules/vesicles and visible epidermal burrows in finger webs, nipples, and buttocks are clues to the diagnosis. Secondary bacterial infection is common. In women, the areolae, nipples, and genitals are frequently affected. Persistent nodules affecting the lower trunk, genitalia, and thighs occur in 7% of patients due to a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to the infestation. Crusted scabies, also known as Norwegian scabies, affects immunocompromised patients (elderly individuals, those with HIV, or transplanted patients) or patients suffering from sensory dysfunction (those infected with leprosy or paraplegia). Mites number in the millions in crusted scabies. However, allergic symptoms such as itch are not as pronounced. Clinical confirmation follows by examining skin scrapings with a light microscope and mineral oil to recognize adult mites, eggs, and or fecal pellets. Epiluminescence microscopy is also useful to see mites and eggs.

Microscopic Features

Eggs, larvae, mites, and excreta are located beneath the stratum corneum when the biopsy includes a burrow (Figure 3.45). The epidermis shows spongiosis with exocytosis of eosinophils and occasionally neutrophils. There is a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with abundant eosinophils, a reaction similar to that seen with other arthropod infestations or assault. If the eosinophilic infiltrate is exuberant, flame figures (eosinophilic granules lining the collagen fibers) may be seen. Scabetic feces (scybala) or eggs are seen more often than the mite itself in vulvar biopsies. The lesions of persistent nodular scabies have a heavy superficial and deep inflammatory infiltrate including lymphocytes, macrophages, plasma cells, eosinophils, and occasionally atypical mononuclear cells; mites are rarely found. Norwegian scabies shows massive hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis containing numerous mites and psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia. The dermal changes resemble those of the papulovesicular variant of scabies.

Glossary of Common Clinical Dermatologic Terms141

Atopy (adj. atopic): Inherited predisposition to hypersensitivity reactions when exposed to certain allergens. Atopic disorders include asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic eczema, and urticaria.

Dermatosis (pl. dermatoses): A nonspecific term used to denote a cutaneous eruption, but generally excluding solitary or multiple benign or malignant skin lesions.

Eczematous: A pattern of inflammatory skin changes characterized in the acute stages by erythema and exudation and in the chronic form by dry, scaling, fissured skin.

Erythema: Redness of the skin due to vasodilatation of cutaneous blood vessels. This may result from inflammation or from physiologic or pathologic changes in cutaneous vasculature.

Hart’s line: A visible line on the inner surface of the labia minora indicating the change from vestibular epithelium (endoderm derived) to skin (ectodermal derived).

Lichenification: Changes seen in skin after long-standing itching and scratching. The skin becomes thickened with exaggeration of normal skin markings. Hyperpigmentation is often a feature.

Lichenoid: Rashes sharing clinical features (of shiny purple-red papules and plaques) with lichen planus. Examples include certain drug eruptions and photosensitive disorders.

Psoriasiform: A pattern of skin inflammation in which scaling plaques are reminiscent of psoriasis. Certain drug eruptions and forms of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma are examples of psoriasiform rashes.

Vulvar vestibule: That part of the vulva lying between Hart’s line and the hymen. Contains the openings of the major and minor vestibular glands.

Glossary of Common Dermatopathologic Terms

Terms applied to the surface keratin layer

Hyperkeratosis: Describes thickening of the keratin layer inappropriate to the site. The thickness of the keratin layer varies according to site; for example, it is normally very thin on the trunk, but very thick on the soles and palms. Hyperkeratosis may be orthokeratotic (in which the keratin is devoid of nuclear remnants) or parakeratotic (in which the keratin layer contains the remnants of nuclei from the underlying epidermis). As a general rule, orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis is associated with a thickening of the granular layer of the epidermis (hypergranulosis) and parakeratotic hyperkeratosis is associated with diminution of the granular layer. Parakeratosis is almost always indicative of an active abnormality in the underlying epidermis, which should be sought when parakeratosis is seen. Orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis with hypergranulosis is seen in lichen simplex chronicus (see Figure 3.6). Parakeratosis may be seen in active acute dermatitis (see Figure 3.3) and may be marked in psoriasis (see Figure 3.7).

Terms applied to the epidermis

Acantholysis: The name given to a process in which there is loss of adhesion and contact between adjacent epidermal keratinocytes such that the cells separate one from the other with breakdown of their linking desmosomal junctions, leading to an increase in the intercellular space. Eventually the intercellular spaces become large and fluid-filled, the separated acantholytic cells tending to become rounded off and floating singly or in small clumps within a variably sized bulla. Acantholysis in the vulva is most commonly seen in Hailey–Hailey disease (see Figure 3.21) and in pemphigus vegetans (see Figure 3.17).

Acanthosis: This term is used to describe inappropriate thickening of the epidermal layer. The thickness of the epidermal layer varies according to site, being thin on the trunk and proximal limbs, and thick in areas such as the palms and soles where the skin is exposed to regular frictional forces. Normally thin epidermis frequently undergoes thickening in response to increased frictional forces; in the vulva this is usually due to repeated scratching (see the section Lichen simplex chronicus). There are particular patterns of acanthosis that may assist in histologic diagnosis.

Basal layer hydropic degeneration: A particular pattern of vacuolation and swelling of the cytoplasm of the basal cells of the epidermis due to the intracellular accumulation of water. This is followed by the death of the affected basal cells, some of which appear as eosinophilic spherical bodies in the basal layer or just beneath, called colloid or Civatte bodies. In the vulva, the combination of basal layer hydropic degeneration and the presence of colloid/Civatte bodies is most frequently seen in the various patterns of lichen planus (see Figure 3.13), but is also seen elsewhere in the body in systemic lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis.

Bullae (sing. bulla): A bulla is another form of blister which is larger than a vesicle (a vesicle is less than 5 mm in diameter and a bulla is greater than 5 mm in diameter). Although most vesicles arise within the epidermis, bullae can arise either within the epidermis or beneath the dermoepidermal junction.

Civatte body: See Basal layer hydropic degeneration.

Exocytosis: Term used to describe an invasion of the epidermis by inflammatory cells (mainly lymphocytes) in association with spongiosis and vesiculation. It is a common histologic feature of inflammatory skin disease of many types.

Papillomatosis: Term used to describe the histologic appearance of marked exaggeration of the dermal papillae by elongation of rete ridges on the dermoepidermal junction and the throwing up into exaggerated folds of the surface epidermis. In the vulva, papillomatosis of epidermis is most frequently seen in condylomata acuminata and papular and keratotic warts.

Psoriasiform acanthosis: In this pattern, the surface of the epidermis is mainly flat but the thickening is due to marked downward elongation of the rete ridges. The epidermis is therefore not uniformly thickened, the areas between rete ridges often showing marked thinning of the epidermis. This is the pattern of epidermal thickening seen most obviously in active psoriasis, hence its name.

Pustule: A pustule is a vesicle that contains inflammatory cells in large numbers, usually neutrophil polymorphs. The presence of the cells renders the vesicle fluid thick and creamy, and the clinically visible vesicle appears white. Pustules may be seen in the vulva in bacterial infections (particularly staphylococcal and streptococcal) and in some forms of psoriasis.

Spongiosis: The name given to focal intercellular edema of the epidermis leading to partial separation of the epidermal cells by edema fluid, particularly in the prickle cell layer. Accumulation of fluid between epidermal cells causes spaces to appear that may coalesce to form fluid-filled vesicles.

Vesicles: Small discrete accumulations of fluid within the epidermis to form a tiny blister, which may be apparent clinically. Vesicle formation usually follows spongiosis (see above).

Terms applied to the dermis

Lichenoid infiltrate: An infiltrate of chronic inflammatory cells (predominantly lymphocytes), which occupies a band-like zone in the upper dermis immediately beneath the dermoepidermal junction. It is a characteristic feature of lichen planus and the very early stages of lichen sclerosus.

Urticaria: Histologically manifested by dermal edema. This may be difficult to detect histologically, but useful clues are the presence in the upper dermis of dilated small lymphatics, and the presence of a distinct pale zone of edema around upper dermal blood vessels. In acute urticaria (rarely biopsied) upper dermal capillaries and venules show margination of neutrophils; in persistent chronic urticaria there is often a scanty perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate in which special stains (e.g., chloroacetate esterase) reveal increased numbers of mast cells. Urticaria of the vulva is an important cause of itchiness, and the histologic diagnosis is frequently missed because the changes are so subtle.

References