Chapter 349 Metabolic Diseases of the Liver

Because the liver has a central role in synthetic, degradative, and regulatory pathways involving carbohydrate, protein, lipid, trace element, and vitamin metabolism, many metabolic abnormalities or specific enzyme deficiencies affect the liver primarily or secondarily (Table 349-1). Much has been learned in the past few years about the biochemical basis, molecular biology, and molecular genetics of metabolic liver diseases. This information has led to more precise diagnostic strategies and novel therapeutic approaches. Liver disease can arise when absence of an enzyme produces a block in a metabolic pathway, when unmetabolized substrate accumulates proximal to a block, when deficiency of an essential substance produced distal to an aberrant chemical reaction develops, or when synthesis of an abnormal metabolite occurs. The spectrum of pathologic changes includes: hepatocyte injury, with subsequent failure of other metabolic functions, often eventuating in cirrhosis, liver tumors, or both; storage of lipid, glycogen, or other products manifested as hepatomegaly, often with complications specific to deranged metabolism (hypoglycemia with glycogen storage disease); and absence of structural change despite profound metabolic effects, as with urea cycle defects. Clinical manifestations of metabolic diseases of the liver mimic infections, intoxications, and hematologic and immunologic diseases (Table 349-2). Many metabolic diseases are detected in expanded newborn metabolic screening programs (Chapter 78). Clues are provided by family history of a similar illness or by the observation that the onset of symptoms is closely associated with a change in dietary habits; for example, in patients with hereditary fructose intolerance, symptoms follow ingestion of fructose. Clinical and laboratory evidence often guides the evaluation. Liver biopsy offers morphologic study and permits enzyme assays, as well as quantitative and qualitative assays of various other constituents. Genetic/molecular diagnostic approaches are also available. Such studies require cooperation of experienced laboratories and careful attention to collection and handling of specimens. Treatment depends on the specific type of metabolic defect, and although individually rare when taken together, metabolic diseases of the liver account for up to 10% of the indications for liver transplantation in children.

Table 349-1 INBORN ERRORS OF METABOLISM THAT AFFECT THE LIVER

DISORDERS OF CARBOHYDRATE METABOLISM

DISORDERS OF AMINO ACID AND PROTEIN METABOLISM

DISORDERS OF LIPID METABOLISM

DISORDERS OF BILE ACID METABOLISM

DISORDERS OF METAL METABOLISM

DISORDERS OF BILIRUBIN METABOLISM

MISCELLANEOUS

* Maple syrup urine disease can be caused by mutations in branched-chain alpha keto dehydrogenase, keto acid decarboxylase, lioamide dehydrogenase, or dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase.

Table 349-2 CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS THAT SUGGEST THE POSSIBILITY OF METABOLIC DISEASE

349.1 Inherited Deficient Conjugation of Bilirubin (Familial Nonhemolytic Unconjugated Hyperbilirubinemia)

Crigler-Najjar Syndrome Type I (Glucuronyl Transferase Deficiency)

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of CN type I is based on the early age of onset and the extreme level of bilirubin elevation in the absence of hemolysis. In the bile, bilirubin concentration is <10 mg/dL compared with normal concentrations of 50-100 mg/dL; there is no bilirubin glucuronide. Definitive diagnosis is established by measuring hepatic glucuronyl transferase activity in a liver specimen obtained by a closed biopsy; open biopsy should be avoided because surgery and anesthesia can precipitate kernicterus. DNA diagnosis is also available and may be preferable. Identification of the heterozygous state in parents also strongly suggests the diagnosis. The differential diagnosis of unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia is discussed in Chapter 96.3.

Crigler-Najjar Syndrome Type II (Partial Glucuronyl Transferase Deficiency)

Bosma PJ. Inherited disorders of bilirubin metabolism. J Hepatol. 2003;38:107-117.

Hafkamp AM. Orlistat treatment of unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia in Crigler-Najjar Disease: a randomized controlled trial. Pediat Res. 2007;62:725-730.

Hsieh TY, Shiu TY, Huang SM, et al. Molecular pathogenesis of Gilbert’s syndrome: decreased TATA-binding protein binding affinity of UGT1A1 gene promoter. Pharmaco Gen. 2007;17(4):229-236.

Kadakol A, Ghosh SS, Sappal BS, et al. Genetic lesions of bilirubin uridine-diphosphoglucuronate glucuronosyltransferase (UGT1A1) causing Crigler-Najjar and Gilbert syndromes: correlation of genotype to phenotype. Hum Mutat. 2000;16:297-306.

Keitel V, Nies AT, Brom M, et al. A common Dubin-Johnson syndrome mutation impairs protein maturation and transport activity of MRP2 (ABCC2). Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;284:G165-G174.

Lysy PA, Najimi M, Stephenne X, et al. Liver cell transplantation for Crigler-Najjar syndrome type I: update and perspectives. World J Gastro. 2008;14(22):3463-3470.

Mor-Cohen R, Zivelin A, Rosenberg N, et al. Identification and functional analysis of two novel mutations in the multidrug resistance protein 2 gene in Israeli patients with Dubin-Johnson syndrome. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:36923-36930.

Strassburg CP. Pharmacogenetics of Gilbert’s syndrome. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9(6):703-715.

349.2 Wilson Disease

Clinical Manifestations

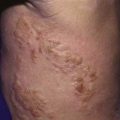

Neurologic disorders can develop insidiously or precipitously, with intention tremor, dysarthria, rigid dystonia, parkinsonism, choreiform movements, lack of motor coordination, deterioration in school performance, or behavioral changes. Kayser-Fleischer rings may be absent in young patients with liver disease but are always present in patients with neurologic symptoms (Fig. 349-1). Psychiatric manifestations include depression, personality changes, anxiety, or psychosis.

Ala A, Walker AP, Ashkan K, et al. Wilson’s disease. Lancet. 2007;369:397-408.

Brewer GJ, Hedera P, Kluin KJ, et al. Treatment of Wilson disease with ammonium tetrathiomolybdate. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:379-385.

Roberts EA, Schilsky ML. Diagnosis and treatment of Wilson disease: an update. Hepatology. 2008;47(6):2089-2111.

Schilsky ML. Wilson disease: new insights into pathogenesis, diagnosis, and future therapy. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2005;7:26-31.

Taly AB, Meenakshi-Sundaram S, Sinha S, et al. Wilson disease. Description of 282 patients evaluated over 3 decades. Medicine. 2007;82:112-121.

349.4 Neonatal Iron Storage Disease

Rand EB, Karpen SJ, Kelly S, et al. Treatment of neonatal hemochromatosis with exchange transfusion and intravenous immunoglobulin. J Pediatr. 2009;155:566-571.

Whitington PF, Kelly S. Outcome of pregnancies at risk for neonatal hemochromatosis is improved by treatment with high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin. Pediatrics. 2008;121(6):e1615-e1621.

349.5 Miscellaneous Metabolic Diseases of the Liver

α1-Antitrypsin Deficiency

A small percentage of patients homozygous for deficiency of the major serum protease inhibitor α1-antitrypsin manifest neonatal cholestasis or later-onset childhood cirrhosis. α1-Antitrypsin, a protease inhibitor synthesized by the liver, protects lung alveolar tissues from destruction by neutrophil elastase (Chapter 385). α1-Antitrypsin is present in >20 different co-dominant alleles, only a few of which are associated with defective protease inhibitors. The most common allele of the protease inhibitor (Pi) system is M, and the normal phenotype is PiMM. The Z allele predisposes to clinical deficiency; patients with liver disease are usually PiZZ homozygotes and have serum α1-antitrypsin levels <2 mg/mL (∼10-20% of normal). The incidence of the PiZZ genotype in the white population is estimated at 1/2,000-4,000. Compound heterozygotes PiZ-, PiSZ, PiZI are not a cause of liver disease alone but can act as modifier genes, increasing the risk of progression in other liver disease such as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatitis C. The null phenotype due to stop codons in the coding exon of the α1-antitrypsin gene or complete deletion of α1-antitrypsin coding exons leads to the complete absence of any protein and causes only lung disease.

Therapy is supportive; liver transplantation has been curative.

Fairbanks KD, Tavill AS. Liver disease in α1-antitrypsin deficiency: a review. Am J Gastro. 2008;103:2136-2141.

Perlmutter DH, Brodsky JL, Balistreri WF, et al. Molecular pathogenesis of α1-antitrypsin deficiency-associated liver disease: a meeting review. Hepatology. 2007;45(5):1313-1323.

Silverman EK, Sandhaus RA. α1-Antitrypsin deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2749-2756.