34 Mesenteric Ischemia

• Severe abdominal pain out of proportion to the findings on physical examination should always raise suspicion for mesenteric ischemia, especially in elderly patients.

• The presence of hypotension, atrial fibrillation, severe cardiovascular disease, or recent myocardial infarction increases the likelihood of mesenteric ischemia.

• No serum marker is sensitive or specific enough to establish or exclude the diagnosis of bowel ischemia.

• Bloody diarrhea is a late finding that indicates mucosal sloughing—do not wait for the appearance of hematochezia or melena to make the diagnosis of mesenteric ischemia.

• Patient survival improves with early mesenteric angiography or surgical intervention (or both).

Epidemiology

Mesenteric ischemia accounts for 0.1% of all hospital admissions and 1% of emergency department (ED) visits for abdominal pain in geriatric patients. Cases of mesenteric vein thrombosis are more difficult to estimate accurately but have been reported at 2 per 100,000 admissions over a period of 20 years at one center.1–3

The overall mortality associated with mesenteric ischemia is between 60% and 93% but rises precipitously once bowel wall infarction has occurred. Mortality remains greatest for acute mesenteric ischemia resulting from obstruction or embolic phenomena. Patients with an early manifestation of NOMI have mortality rates of 50% to 55%, whereas patients with mesenteric vein thrombosis have a 15% mortality at 30 days.1–3 Those affected by chronic mesenteric ischemia have a more prolonged course, are relatively protected by dual blood supply, and present the physician with more numerous chances for intervention.

Pathophysiology

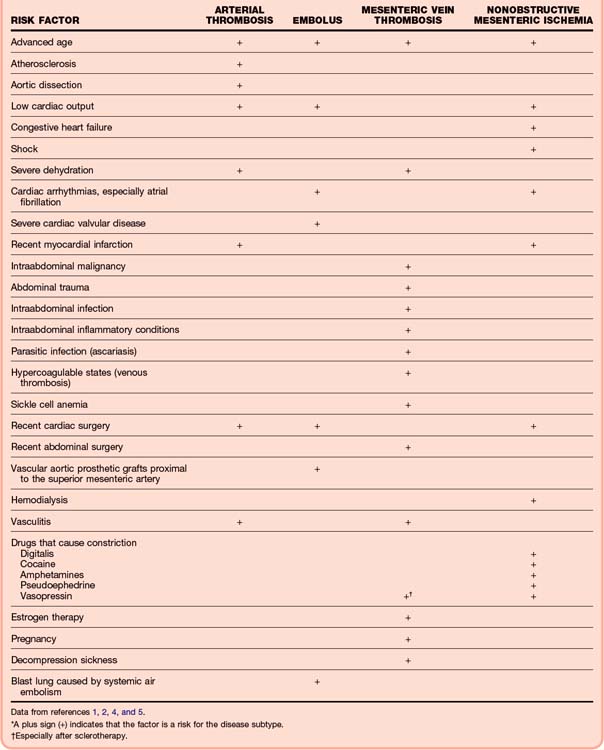

Any patient with advanced age, atherosclerosis, thromboembolic disease, atrial fibrillation, and processes leading to chronic low-flow states is at risk for the development of arterial mesenteric ischemia (Tables 34.1 and 34.2).1,2,4,5 Mesenteric venous obstruction carries its own separate risk factors, which are similar to those for venous thrombosis anywhere in the body.

| DISEASE | INCIDENCE (%)* |

|---|---|

| Superior mesenteric artery (SMA) embolism: | 50 |

| The SMA is susceptible to embolism because of large vessel caliber and a narrow angle of departure from the aorta. | |

| The proximal SMA is most commonly obstructed within 6-8 cm of the aorta. | |

| Nonocclusive ischemia | 25 |

| SMA thrombosis | 20 |

| Mesenteric venous thrombosis | 5 |

* Percentage of all cases of acute mesenteric ischemia.

Bowel perfusion is generally preserved during periods of hypotension; therefore, NOMI represents failure of the normal autoregulatory systems.2,6,7 Patients with chronic renal failure may have bowel ischemia after hemodialysis, probably from hypoperfusion, which promotes preferential shunting of blood from the splanchnic circulation to preserve flow to the cardiac and cerebrovascular systems.

Although acute mesenteric vein thrombosis accounts for a small proportion of cases of ischemic bowel disease (5% to 10%), the ease of diagnosis with computed tomography (CT) has allowed identification of a greater number of patients with venous thrombosis. Symptoms are even less specific than those of arterial obstruction and are manifested over a longer period before bowel infarction occurs. Thrombus secondary to hypercoagulable states develops first in the smaller vessels and later progresses into the larger veins; clots associated with cirrhosis, neoplasm, or local injury (operative, trauma) start at the site of obstruction and evolve distally.4

There is a significant array of collateral blood vessels and flow patterns. The small intestine is especially vulnerable to ischemia, however, because the terminal arterioles enter the intestinal wall without collateral pathways.4 Splanchnic blood flow requirements vary continuously but can account for up to 35% of cardiac output.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Classic Presentation

Clues to diagnosis of the various ischemic bowel diseases are as follows:

• Acute abdominal pain followed by rapid and forceful evacuation of the bowels (vomiting or diarrhea) strongly suggests an embolic phenomenon in the SMA.

• Long-standing abdominal pain (weeks to months), which is then followed by acute worsening, suggests intestinal angina and SMA thrombosis.

• Patients with risk factors for NOMI may have unexplained abdominal distention or gastrointestinal bleeding; pain is totally absent in up to 25% of these patients, and unexplained distention may herald infarction.

![]() Documentation

Documentation

Onset, severity, and duration of symptoms

Presence of melena or hematochezia

Presence or absence of risk factors

Vital signs: evidence of shock, sepsis

Findings of cardiac, full abdominal, genitourinary, and rectal examinations

Emergency department course: times of discussions with consultants, discussions with family, code status, availability of testing, treatments, delays

Variations in Presentation

Patients with mesenteric atherosclerosis may have symptoms of abdominal angina, classically manifested as postprandial pain. As a result, fear of eating, early satiety, weight loss, and altered bowel habits develop. This syndrome occurs in up to 50% of patients in whom thrombotic mesenteric ischemia eventually develops.2

Differential Diagnosis

Few diagnoses portend a more serious course and risk for mortality than mesenteric ischemia does. Patients at risk for AMI are generally also at risk for aortic disease. Other items in the differential diagnosis are listed in Box 34.1.

Diagnostic Testing

Angiography and Computed Tomographic Angiography

Mesenteric angiography provides direct visualization of the vasculature and remains a valuable method of evaluation in patients with suspected bowel ischemia (Table 34.3). Angiography is both sensitive (74% to 100%) and specific (100%); the test also differentiates between occlusive and nonocclusive disease. Patients who undergo angiography in timely fashion have better survival; mortality rates of 70% to 90% are observed when bowel infarction has occurred.4

| DISEASE | FINDINGS |

|---|---|

| Superior mesenteric artery (SMA) embolus |

Data from Burns BJ, Brandt LJ. Intestinal ischemia. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2003;32:1127-43.

CT angiography (CTA) is largely replacing standard angiography because it is more readily available and more quickly accomplished. A metaanalysis published in 2010 confirmed CTA as the first-line imaging modality because of its high sensitivity (93%) and specificity (96%).8 CTA is clearly more advantageous in the ED; interventional radiology (IR) involvement later offers additional treatment advantages in the perioperative or observational inpatient phases.

Standard angiography allows local administration of thrombolytic or vasodilatory therapy concomitant with the diagnostic procedure, thereby improving mortality. The emergency physician (EP) must weigh the diagnostic and therapeutic advantages of CTA or standard angiography against concerns for dye administration in patients susceptible to renal insufficiency (almost every patient with mesenteric ischemia), availability of an interventional radiologist, stability of the patient, and delays in surgical intervention (Fig. 34.1). In all cases of suspected mesenteric ischemia, the surgeon should be contacted for involvement before or simultaneously with the ordering of advanced diagnostic testing, with the caveat that any delay in diagnosis and operative intervention increases mortality.

Computed Tomography

Early CT findings of acute arterial ischemia are poorly sensitive and nonspecific; late findings identify disease in patients with prolonged ischemia and probable necrosis (Table 34.4). CT is the imaging test of choice only for mesenteric vein thrombosis, for which it has a diagnostic accuracy of 90%.6 Angiography may be avoided when the diagnosis of SMV thrombosis is confirmed by standard CT, although it may still be used for catheter placement and local papaverine infusion.

Table 34.4 Computed Tomography Findings in Ischemic Bowel Disease

| DISEASE | FINDINGS |

|---|---|

| Arterial ischemia: | |

| Early | |

Data from Burns BJ, Brandt LJ. Intestinal ischemia. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2003;32:1127-43.

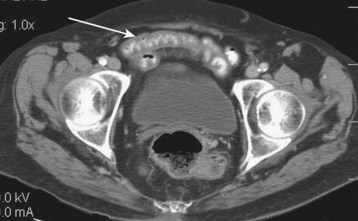

Other Imaging Modalities

Plain radiographs have no role in the evaluation of acute ischemic disease but are frequently ordered to quickly assess for the presence of processes such as a perforated viscus and free air. Plain film findings are usually normal early in the course of illness. Late findings suggest mucosal edema and hemorrhage and include bowel wall thickening, ileus, and thumbprinting, which describes the appearance of bowel wall edema, as though a thumb had been pressed into the bowel wall and caused an indentation. Pneumatosis intestinalis, the presence of gas in the bowel wall, may also be seen. Air in the portal venous system may likewise be seen (Fig. 34.2). Late findings are associated with a poor prognosis.

Laboratory Studies

No laboratory studies are confirmatory of mesenteric ischemia. Delaying diagnostic imaging by waiting for laboratory results decreases survival. Laboratory abnormalities are nonspecific and occur late in disease (Box 34.2)4,7,9; their absence in no way rules out acute ischemia.5,9

Levels of ischemia-modified albumin increase in AMI, as well as in several other vascular diseases; their potential role in early diagnosis remains undefined.10

Tips and Tricks

Suspect the disease, especially in the elderly.

Do not delay obtaining imaging or consultation while waiting for laboratory test results.

Rectal findings are often normal.

An elevated serum amylase value may suggest bowel infarction, not pancreatitis.

A patient with a history of deep vein thrombosis is at risk for superior mesenteric vein thrombosis, which tends to develop less acutely than other causes of ischemia.

Bowel ischemia promotes acidosis, lethargy, and confusion in the elderly; altered mental status complicates up to 30% of cases.

Treatment

Early surgical consultation is a high priority in patients with suspected mesenteric ischemia. Initial ED management should include volume resuscitation, treatment of contributing cardiac abnormalities (dysrhythmias, heart failure, hypotension), and administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics (Box 34.3). Administration of antibiotics decreases the infectious complications of bowel infarction when they are given early to patients with suspected ischemia.6 The most difficult process for the EP is to see past the present crisis and perform a complete and thorough evaluation of the patient; atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response is a common finding, but hypotension and the altered mental status attributed to it may actually be due to the resultant mesenteric ischemia and sepsis. Look for and pay attention to the other findings pointing to coexisting diagnosis.

Box 34.3 Emergency Department Treatment

Fluid resuscitation and oxygen supplementation; treat shock as indicated

Apply telemetry monitoring and obtain an electrocardiogram

Broad-spectrum antibiotics to cover bowel flora

Nasogastric tube and Foley catheter

Address comorbid conditions with specific treatment

Surgery consultation as soon as the diagnosis is strongly suspected

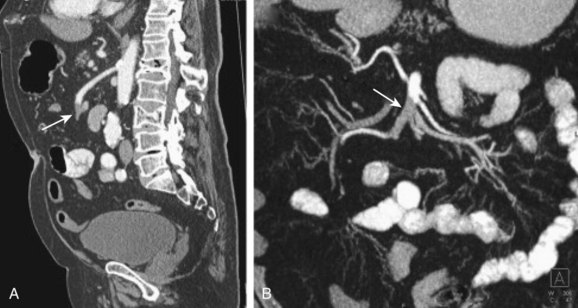

Surgical exploration is mandatory when peritonitis is present to remove necrotic bowel and restore blood flow via arterial bypass or embolectomy. A second-look procedure is generally performed 12 to 24 hours after the first operation to evaluate for additional loss of bowel (Fig. 34.3).

Fig. 34.3 Eighty-year-old man with acute abdominal pain.

(From Horton KM, Fishman EK. CT angiography of the mesenteric circulation. Radiol Clin North Am 2010;48:331-45, viii.)

Anticoagulation is routinely administered postoperatively to patients with mesenteric vein thrombosis. Immediate heparinization after surgery decreases the chance of thrombus recurrence from 25% to 13%, prevents disease progression, and reduces mortality from 50% to 13%.11 With the absence of peritonitis, anticoagulation may be used in lieu of surgery. If deemed successful after close observation, anticoagulation therapy is generally continued for 3 to 6 months.

Additional therapeutic possibilities currently being explored include the use of heparin-binding epithelial growth factor–like growth factor to protect the intestines and other organs from ischemic injury, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty of the SMA, tolazoline and nitroglycerin as local intraarterial infusions, and prostaglandin E1 infusions in patients with NOMI.12–16

FolLow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Have an early discussion with the patient and family regarding the severity of the illness, need for an aggressive approach to diagnosis and treatment, and high mortality.

Determine the patient’s and the family’s desire for full resuscitation efforts given the mortality rate associated with mesenteric ischemia.

Bjorck M, Wanhainen A. Nonocclusive mesenteric hypoperfusion syndromes: recognition and treatment. Semin Vasc Surg. 2010;23:54–64.

Horton KM, Fishman EK. CT angiography of the mesenteric circulation. Radiol Clin North Am. 2010;48:331–345.

Menke J. Diagnostic accuracy of multidetector CT in acute mesenteric ischemia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiology. 2010;256:93–101.

1 Boley SJ, Brandt LJ, Sammartano RJ. History of mesenteric ischemia: the evolution of a diagnosis and management. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77:275–288.

2 Klempnauer J, Grothues E, Bektas H, et al. Long term results after surgery for acute mesenteric ischemia. Surgery. 1997;121:239–243.

3 Bugliosi TF, Meloy TD, Vukov LF. Acute abdominal pain in the elderly. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19:1383–1386.

4 Burns BJ, Brandt LJ. Intestinal ischemia. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2003;32:1127–1143.

5 Sanson TG, O’Keefe KP. Evaluation of abdominal pain in the elderly. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1996;14:615–627.

6 Sudhakar CB, Al-Hakeem M, McArthur JD, et al. Mesenteric ischemia secondary to cocaine abuse: case reports and literature review. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1053–1054.

7 Diamond S, Emmett M, Henrich WL. Bowel infarction as a cause of death in dialysis patients. JAMA. 1986;256:2545–2547.

8 Menke J. Diagnostic accuracy of multidetector CT in acute mesenteric ischemia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiology. 2010;256:93–101.

9 Martinez JP, Hogan GJ. Mesenteric ischemia. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2004;22:909–928.

10 Gunduz A, Turedi S, Mentese A, et al. Ischemia-modified albumin in the diagnosis of acute mesenteric ischemia: a preliminary study. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:202–205.

11 Grieshop RJ, Dalsing MC, Cikrit DF, et al. Acute mesenteric vein thrombosis: revisited in a time of diagnostic clarity. Am Surg. 1992;57:573.

12 James IA, Chen CL, Huang G, et al. HB-EGF protects the lungs after intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Surg Res. 2010;163:86–95.

13 Fioole B, van de Rest HJ, Meijer JR. Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty and stenting as first-choice treatment in patients with chronic mesenteric ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:386–391.

14 Cortese B, Limbruno U. Acute mesenteric ischemia: primary percutaneous therapy. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;75:283–285.

15 Sommer CM, Radeleff BA. A novel approach for percutaneous treatment of massive nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia: tolazoline and glycerol trinitrate as effective local vasodilators. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;73:152–155.

16 Kamimura K, Oosaki A, Sugahara S, et al. Survival of three nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia patients following early diagnosis by multidetector row computed tomography and prostaglandin E1 treatment. Intern Med. 2008;47:2001–2006.