CHAPTER 28 Menopause

Introduction

Increasing life expectancy and decreasing fertility rates mean that the number of older people is projected to grow significantly worldwide. Between 1950 and 2007, the number of people aged 65 years and older increased from 5% to 7% (Population Reference Bureau 2007). Life expectancy at birth in women in countries such as the UK is currently 81 years (World Health Organization 2006). With the menopause occurring in the early 50s, managing the postreproductive period, which extends over several decades, is an increasingly important public health issue.

The Menopause: Definitions and Physiology

The menopause is the cessation of the menstrual cycle and is caused by ovarian failure. The term is derived from the Greek menos (month) and pausos (ending). The median age at which the menopause occurs is 52 years. The age at menopause is determined by genetic and environmental factors (Gold et al 2001, Elias et al 2003, Reynolds and Obermeyer 2005, Gosden et al 2007). Japanese race and ethnicity may be associated with later age of natural menopause, while Down’s syndrome is associated with an early menopause. Growth restriction in late gestation, low weight gain in infancy, starvation in early childhood and smoking may be associated with an earlier menopause. However, being breast fed, higher childhood cognitive ability and increasing parity increase the age of menopause.

Definitions

Various definitions are in use and are detailed below (Utian 1999, World Health Organization 1994).

Ovarian function and the menopause

Each ovary receives a finite endowment of oocytes, the numbers of which are maximal at 20–28 weeks of intrauterine life. From mid-gestation onwards, a logarithmic reduction in these germ cells occurs until, approximately 50 years later, the stock of oocytes is depleted (Burger et al 2008). The main steroid hormones produced by the ovary are oestradiol, progesterone and testosterone. Premenopausally, ovarian function is controlled by the two pituitary gonadotrophins: follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). FSH is controlled primarily by the pulsatile secretion of hypothalamic GnRH, and is modulated by the negative feedback of oestradiol and progesterone and the ovarian peptide inhibin B. The peptide is a major regulator of FSH secretion and a product of small antral follicles. Its levels respond to the early-follicular-phase increase and decrease in FSH. The age-related decrease in ovarian primordial follicle numbers, which is reflected in a decrease in the number of small antral follicles, leads to a decrease in inhibin B, which in turn leads to an increase in FSH. LH is principally controlled by GnRH, with negative feedback control from oestradiol and progesterone for most of the cycle; positive oestradiol feedback generates the mid-cycle surge in levels of LH that triggers ovulation.

Stages of reproductive ageing

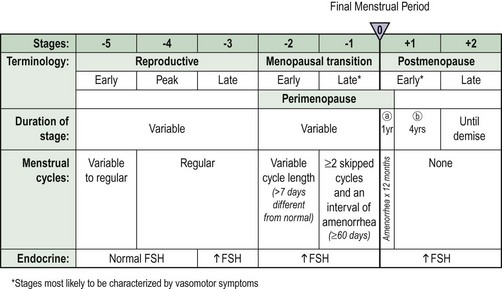

A staging system that uses the final menstrual period as the anchor to describe reproductive ageing was proposed by the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW) (Soules et al 2001) (Figure 28.1). This incorporates both menstrual cycle and hormonal parameters. Progression through the STRAW stages is associated with elevations in serum FSH, LH and oestradiol, and decreases in luteal-phase progesterone.

Menopause symptoms

Menopause symptoms include hot flushes and night sweats, depression, tiredness and sexual problems. Symptom reporting varies between cultures (Melby et al 2005). Approximately 70% of women in Western cultures will experience vasomotor symptoms, such as hot flushes and night sweats. However, Japanese women have fewer menopausal complaints than their North American counterparts. Furthermore, rural Mayan women living in the Yucatan, Mexico do not report either hot flushes or night sweats.

Vasomotor symptoms

Flushes are episodes of inappropriate heat loss mediated by cutaneous vasodilation over the upper trunk. Sympathetic nervous control of blood flow in the skin is impaired in women with menopausal flushes, in whom reflex constriction to an ice stimulus cannot be elicited. More recently, serotonin and its receptors in the central nervous system have been implicated. Hot flushes and night sweats may begin before periods stop, and their prevalence is highest in the first year after the final menstrual period. Although they are usually present for less than 5 years, some women will continue to flush beyond the age of 60 years. Although women with a higher level of education seem to have fewer symptoms, evidence about the effect of exercise is conflicting (Daley et al 2007). Current smoking and high body mass index (BMI) may also predispose a woman to more severe or frequent hot flushes (Whiteman et al 2003).

Psychological symptoms

Psychological symptoms include depressed mood, anxiety, irritability, mood swings, lethargy and lack of energy. Transition to menopause confers a higher risk for development of depression, and multiple risk factors such as previous psychological problems and current life stresses appear to increase risk (Frey et al 2008).

Sexual dysfunction

Although women may stay sexually active until their eight or ninth decades of life, sexual problems are common. It has been estimated that they affect approximately one in two women. Interest in sex declines in both sexes with increasing age, and this change is more pronounced in women. The term ‘female sexual dysfunction’ is now used. An international classification system was elaborated by the International Consensus Development Conference on Female Sexual Dysfunction (Table 28.1) (Basson et al 2000). The most prevalent sexual problems among women are low desire (43%), difficulty with vaginal lubrication (39%) and inability to climax (34%) (Lindau et al 2007).

| Classification | Definition |

|---|---|

| I Sexual desire disorders | |

| A Hypoactive sexual desire disorder | The persistent or recurrent deficiency (or absence) of sexual fantasies/thoughts and/or desire for, or receptivity to, sexual activity, which causes personal distress |

| B Sexual aversion disorder | The persistent or recurrent phobic aversion and avoidance of sexual contact with a sexual partner, which causes personal distress |

| II Sexual arousal disorders | The persistent or recurrent inability to attain or maintain sufficient sexual excitement, causing personal distress, which may be expressed as a lack of subjective excitement, or genital (lubrication/swelling) or other somatic responses |

| III Orgasmic disorder | The persistent or recurrent difficulty, delay in or absence of attaining orgasm after sufficient sexual stimulation and arousal, which causes personal distress |

| IV Sexual pain disorders | |

| A Dyspareunia | The recurrent or persistent genital pain associated with sexual intercourse |

| B Vaginismus | The recurrent or persistent involuntary spasm of the musculature of the outer third of the vagina, which interferes with vaginal penetration and causes personal distress |

| C Non-coital sexual pain disorders | Recurrent or persistent genital pain induced by non-coital sexual stimulation |

Each of the categories above is subtyped on the basis of the medical history, physical examination and laboratory tests as: (A) lifelong vs acquired; (B) generalized vs situational; or (C) aetiology (organic, psychogenic, mixed or unknown).

Adapted from Basson R, Berman J, Burnett A, et al. Report of the international consensus development conference on female sexual dysfunction: definitions and classifications. J Urol 2000;163:888-93.

Chronic Conditions Affecting Postmenopausal Health

These include cardiovascular disease (CVD), osteoporosis, dementia and urinary incontinence.

Osteoporosis

Definitions of osteoporosis according to the World Health Organization

The World Health Organization’s definitions are based on measurement of bone mineral density (BMD) (Table 28.2). Severe osteoporosis is defined as the presence of a fragility or minimal trauma fracture and low BMD (T-score less than −2.5). The T-score is the number of standard deviations by which the bone in question differs from the young normal mean. Although BMD is a major contributor to risk, other factors, including age, BMI and falls, play a part in determining whether a person will get a fracture. The FRAX tool has been developed by the World Health Organization to evaluate fracture risk (Kanis et al 2008). It is based on individual patient models that integrate the risks associated with clinical risk factors as well as femoral neck BMD. The clinical risk factors comprise BMI (as a continuous variable), a prior history of fracture, a parental history of hip fracture, use of oral glucocorticoids, rheumatoid arthritis and other secondary causes of osteoporosis, current smoking and alcohol intake of 3 or more units/day. The FRAX algorithms give the 10-year probability of hip and other major osteoporotic fractures.

Table 28.2 Definitions of osteoporosis according to the World Health Organization

| Description | Definition |

|---|---|

| Normal | BMD value between −1 SD and +1 SD of the young adult mean (T-score −1 to +1) |

| Osteopenia | BMD reduced between −1 and −2.5 SD from the young adult mean (T-score −1 to −2.5) |

| Osteoporosis | BMD reduced by equal to or more than −2.5 SD from the young adult mean (T score −2.5 or lower) |

BMD, bone mineral density; SD, standard deviation.

Urogenital atrophy and urinary incontinence

Urinary incontinence affects millions of women throughout the world. It affects the quality of life of women of all ages and poses a large financial burden on society. The population-based prevalence of urinary incontinence in the USA has been estimated to be 45% (Melville et al 2005). Prevalence increased with age, from 28% for women aged 30–39 years to 55% for women aged 80–90 years. Eighteen percent of respondents reported severe urinary incontinence. The prevalence of severe urinary incontinence also increased notably with age, from 8% for women aged 30–39 years to 33% for women aged 80–90 years. Other surveys have reported similar findings.

Therapeutic Options

Oestrogen-based hormone replacement therapy

A wide variety of oestrogen-based preparations are available worldwide, which feature different strengths, combinations and routes of administration (Clinical Knowledge Summaries 2009). Various designations are used: hormone replacement therapy (HRT), hormone therapy, oestrogen therapy, and oestrogen and progestogen therapy for combined preparations (sequential or continuous combined).

Oestrogens

Two types of oestrogen are available: natural and synthetic. Natural oestrogens include oestradiol, oestrone and oestriol. Conjugated equine oestrogens contain approximately 50–65% oestrone sulphate, and the remainder consists of equine oestrogens, mainly equilin sulphate. These are also classified as ‘natural’. The generally accepted minimum bone-sparing doses of oestrogen are listed in Table 28.3, although increasing evidence shows that even lower doses may be effective. Synthetic oestrogens, such as ethinyl oestradiol used in the combined oral contraceptive pill, are generally considered to be unsuitable for HRT because of their greater metabolic impact, apart for treating young women with premature ovarian failure (POF).

| Oestrogen | Dose |

|---|---|

| Oestradiol oral | 1–2 mg |

| Oestradiol patch | 25–50 µg |

| Oestradiol gel | 1–5 g* |

| Oestradiol implant | 50 mg every 6 months |

| Conjugated equine oestrogens | 0.3–0.625 mg daily |

Women’s Health Initiative and Million Women Study

Publication of the results of the US Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) and UK Million Women Study (MWS) since 2002 has led to considerable uncertainties regarding the use of oestrogen-based HRT (Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators 2002, Million Women Study Collaborators 2003, Women’s Health Initiative Steering Committee 2004). Several publications have questioned the design, analysis and conclusions of both these studies (Shapiro 2007). For example, in the WHI, women in their 70s were given HRT for the first time, which does not reflect usual clinical practice. In the MWS, it was not easy to control for differences between attendees and non-attendees of the National Health Service Breast Screening Programme and between attendees who agreed or declined to participate in the study. Both studies were undertaken in women aged 50 years and over, and their findings cannot be extrapolated to younger women such as those with premature menopause in their 20s and 30s.

Women’s Health Initiative

The WHI is a large complex series of studies designed in the early 1990s with follow-up until 2010 of strategies for the primary prevention and control of some of the most common causes of morbidity and mortality among healthy postmenopausal women aged 50–79 years. It consisted of a randomized-controlled trial and an observational study. The randomized trial considered not only HRT but also calcium and vitamin D supplementation and a low-fat diet (Box 28.1). If eligible, women could choose to enrol in one, two or all three components of the randomized trial. The randomized trial involved 68,132 women (mean age 63 years): conjugated equine oestrogens (0.625 mg) alone (n = 10,739 hysterectomized women), conjugated equine oestrogens (0.625 mg) in combination with medroxyprogesterone acetate (2.5 mg) (n = 16,608 non-hysterectomized women), low-fat diet (n = 48,835), and calcium and vitamin D supplementation (n = 36,282). Women screened for the clinical trial who were ineligible or unwilling to participate in the controlled trial (n = 93,676) were recruited into an observational study that assessed new risk indicators and biomarkers for disease.

Box 28.1 Interventions evaluated by the Women’s Health Initiative

Benefits, risks and uncertainties of oestrogen-based hormone replacement therapy

Benefits

Vasomotor symptoms

There is good evidence from randomized placebo-controlled studies, including the WHI, that oestrogen is effective for the treatment of hot flushes, and improvement is usually noted within 4 weeks (Simon and Snabes 2007). It is more effective than non-hormonal preparations such as clonidine and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (see below). The most common indication for HRT prescription is relief of vasomotor symptoms, and it is often used for less than 5 years.

Urogenital symptoms and sexuality

Urogenital symptoms respond well to oestrogen administered either topically or systemically. In contrast to vasomotor symptoms, improvement may take several months. Recurrent urinary tract infections may be prevented by vaginal but not oral oestrogen replacement (Perrotta et al 2008). Topical oestrogens may have a weak effect on urinary urge incontinence, but no improvement of stress incontinence. Long-term treatment is often required as symptoms can recur when therapy is stopped. Sexuality may be improved with oestrogen alone, but testosterone may also be required, especially in young oophorectomized women.

Osteoporosis

There is evidence from randomized-controlled trials (including the WHI) that HRT reduces the risk of both spine and hip fractures, as well as other osteoporotic fractures (Writing Group on Osteoporosis for the British Menopause Society Council 2007). Most epidemiological studies suggest that continuous and lifelong use is required for fracture prevention. However, there is now some evidence that a few years of treatment with HRT around the time of the menopause may have a long-term effect on fracture reduction. While alternatives to HRT use are available for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis in elderly women (see below), oestrogen still remains the best option, particularly in younger (<60 years) and/or symptomatic women. Few data are available on the efficacy of alternatives such as bisphosphonates in women with POF.

Risks

Breast cancer

HRT appears to confer a similar degree of risk as that associated with late natural menopause (2.3% compared with 2.8% per year, respectively). There is no increased risk in HRT users with a premature menopause (Ewertz et al 2005).

The increased risk of breast cancer with combined HRT compared with oestrogen alone has to be balanced against the reduction in risk of endometrial cancer provided by progestogen addition. The increased risk of breast cancer with long-term use seems to be limited to lean women (BMI <25 kg/m2) in most studies. Also, the increased risk of breast cancer with HRT is low and similar to the risk conferred by obesity, being tall, nulliparity or late age at first full-term pregnancy, and is lower than that conferred by certain inherited genetic mutations or mantle radiotherapy (American Cancer Society 2009).

Also, the risk of breast cancer decreases after stopping HRT, and after 5 years, the risk of breast cancer is no greater than that in women who have never been exposed to HRT. The incidence of breast cancer has been decreasing in the USA and this has been attributed to declining HRT use since publication of the WHI. However, the decrease started in 1998, predating the first WHI publication (Li and Daling 2007).

Endometrial cancer

Unopposed systemic oestrogen replacement therapy increases the risk of endometrial cancer (Weiderpass et al 1999). Sequential progestogen addition, especially when continued for more than 5 years, does not eliminate this risk completely. This has also been found with monthly- and long-cycle HRT. No increased risk of endometrial cancer has been found with continuous combined regimens. Very low doses of systemic oestrogen (0.014 µg/day transdermal oestradiol patch) do not seem to stimulate the endometrium, but studies are limited and require confirmation (Simon and Snabes 2007).

Venous thromboembolism

HRT increases the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) two-fold, with the highest risk occurring in the first year of use (Canonico et al 2008). However, the absolute risk is small, being 1.7 per 1000 in women over 50 years of age not taking HRT. Advancing age, obesity and an underlying thrombophilia such as factor V Leiden increase the risk of VTE significantly. Randomized trial data strongly suggest that women who have previously suffered a VTE have an increased risk of recurrence in the first year of HRT use. However, transdermal HRT may be associated with a lower risk, even in women with a thrombophilia.

Gallbladder disease

The WHI confirmed the observation of the Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study published in 1998 that oral HRT increases the risk of gallbladder disease. However, the MWS found that transdermal therapy confers a lower risk than oral therapy (Liu et al 2008). Gallbladder disease increases with ageing and with obesity, and HRT users may have silent pre-existing disease.

Uncertainties

CHD primary prevention

Until the late 1990s, oestrogen was thought to protect against CHD (Rees and Stevenson 2008). Many cohort studies showed that HRT was associated with a 40–50% reduction in the incidence of CHD. The effects were the same for both oestrogen alone and combined HRT. However, the WHI did not confirm these observational studies. It has become apparent that there are differences between regimens, and that the timing of HRT initiation may be crucial. The WHI found an early, albeit transient, increase in coronary events in the combined arm but not the oestrogen-alone arm. In the WHI oestrogen-alone arm, there was a non-significant reduction in CHD, which was most marked in younger women (50–59 years). With regard to timing, women in the WHI who started combined HRT within 10 years of the menopause had a lower risk of CHD than women who started later (Rossouw et al 2007). Combining the two HRT arms found that women who initiated hormone therapy closer to the menopause tended to have reduced CHD risk compared with the increase in CHD risk among women who initiated hormone therapy more distant from the menopause. While transdermal oestrogen has less of an effect on coagulation than oral therapy due to avoidance of the first liver pass, it is uncertain whether transdermal delivery is better than oral delivery in terms of CHD risk.

CHD secondary prevention

Although angiographic and cohort studies such as the Nurses’ Health Study suggested a role of oestrogen in the secondary prevention of CHD, this has not been confirmed in randomized-controlled trials with both oral and transdermal therapy (Grodstein et al 2006).

Stroke

Interpretation of observational studies on HRT and stroke is difficult because of differences in design and failure to distinguish between ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke (Billeci et al 2008). Both arms of the WHI found an increase in ischaemic stroke but not haemorrhagic stroke. However, age or time since menopause did not affect the risk of stroke. In addition, in women who have experienced a previous ischaemic stroke, oestrogen replacement does not reduce mortality or recurrence as evidenced by randomized-controlled trials.

Dementia and cognition

While oestrogen may delay or reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s disease, it does not seem to improve established disease (Barber et al 2005). It is unclear if there is a critical age or duration of treatment for exposure to oestrogen to have an effect on prevention, but there may be a window of opportunity in the early postmenopause when the pathological processes that lead to Alzheimer’s disease are starting and when HRT may have a preventive effect. The WHI found an increased risk of dementia and lower cognitive function in HRT users, but only in women aged over 75 and 65 years, respectively.

Tibolone

Tibolone is effective in the treatment of menopausal symptoms. It conserves bone mass and reduces the risk of vertebral and non-vertebral fractures, particularly in patients who have already had a vertebral fracture. It also reduces the risk of invasive breast cancer and colon cancer. However, it does not significantly reduce the risk of hip fracture and it increases the risk of stroke (Cummings et al 2008). The LIFT study also showed that tibolone does not have a deleterious effect on CHD or VTE (Cummings et al 2008). The MWS showed an increased risk of breast cancer and endometrial cancer. However, the increased risk of endometrial cancer has not been confirmed in randomized-controlled trials (Archer et al 2007). The LIBERATE randomized trial of tibolone in breast cancer survivors was discontinued early in 2007 as there was an excess of breast cancer recurrences in the group of women randomized to receive tibolone (Kenemans et al 2009).

Non-Oestrogen-Based Treatments for Menopausal Symptoms

Non-oestrogen-based treatments are used to treat hot flushes and symptoms of urogenital atrophy. These can be either hormonal or non-hormonal (Writing Group for the British Menopause Society Council 2008).

Non-hormonal

Non-Oestrogen-Based Therapy for Osteoporosis

A wide range of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions are available (Table 28.4) (Writing Group on Osteoporosis for the British Menopause Society Council 2007). There are very few data regarding long-term efficacy for reducing fractures (i.e. more than 10 years of treatment) and safety of combinations of therapy. Most of these therapies have been studied in elderly women (>60 years) who have osteoporosis or who are at increased risk of the disease. Little is known about their efficacy and safety in women with premature menopause and effects on the developing fetal skeleton. This is of importance because of the long (many years) half-life of bisphosphonates and strontium ranelate.

Table 28.4 Interventions for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis

| Spine | Hip | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Bisphosphonates | ||

| Etidronate | A | B |

| Alendronate | A | A |

| Risedronate | A | A |

| Ibandronate | A | ND |

| Zoledronic acid | A | A |

| 2. Calcium and vitamin D | ND | A |

| 3. Calcium | A | B |

| 4. Calcitriol | A | ND |

| 5. Calcitonin | A | B |

| 6. Oestrogen | A | A |

| 7. Raloxifene | A | ND |

| 8. Strontium ranelate | A | A |

| 9. Parathyroid hormone peptides | A | ND |

ND, not demonstrated.

The levels of evidence for the various agents are:

A = meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials (RCTs) or from at least one RCT/from at least one well-designed controlled study without randomization;

B = from at least one other type of well-designed quasi-experimental study or from well-designed non-experimental descriptive studies, e.g. comparative studies, correlation studies, case–control studies.

Pharmacological interventions

Raloxifene

Raloxifene is a selective oestrogen receptor modulator (SERM). These compounds possess oestrogenic actions in certain tissues and antioestrogenic actions in others (Palacios 2007). Other SERMs such as bazedoxifene, arzoxifene, lasofoxifene and ospemifene are currently being evaluated.

Future developments

New treatments are focusing on inhibition of bone turnover (McClung 2007). Receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL) is a pivotal regulator of osteoclast activity that provides a new therapeutic target. Denosumab, a highly specific anti-RANKL antibody, reduces bone resorption. Pharmacokinetics of the antibody allow dosing by subcutaneous injection every 3 or 6 months.

Non-pharmacological interventions

Calcium and vitamin D

Provision of adequate dietary or supplemental calcium and vitamin D is an essential part of osteoporosis management, and is the placebo component of clinical trials of agents such as bisphosphonates. Most studies show that approximately 1.5 g elemental calcium is necessary to preserve bone health in women who are not taking HRT. However, the effects of calcium and vitamin D supplements, alone or in combination, on fracture are contradictory and may depend on the study population and compliance with therapy (Tang et al 2007, Lin and Lane 2008). For example, people in sheltered accommodation or residential care may be more frail, have lower dietary intakes of calcium and vitamin D, and are at higher risk of fracture than those living in the community.

Hip protectors

Hip protectors are used to reduce the impact of falling directly on the hip, but evidence of efficacy is conflicting in both community and institutional studies. A systematic review found no evidence of the effectiveness of hip protectors from studies in which randomization was by individual patient within an institution or those living in their own homes (Parker et al 2006).

Diet and exercise

Maintaining a good diet and regular exercise are essential for healthy ageing and reducing the risk of CVD, osteoporosis, urinary incontinence and dementia (Salerno-Kennedy and Rees 2007).

Dietary components

It has been suggested that antioxidant supplements may reduce mortality. However, a systematic review found that vitamin A, beta-carotene, and vitamin E supplements may increase mortality (Bjelakovic et al 2008). No detrimental effects were found with vitamin C or selenium. Of note, most trials in the systematic review investigated the effects of supplements administered at higher doses than those commonly found in a balanced diet, and some of the trials used doses above the recommended daily allowances. These trials should not deter women from consuming fruit and vegetables which contain other substances such as fibre and flavonoids.

Functional foods

A functional food may be defined as a food with health-promoting benefits and/or disease-preventing properties over and above its usual nutritional value (Rudkovska 2008). Functional foods are also known as ‘nutraceuticals’ or ‘designer foods’. They encompass a broad range of products, ranging from foods generated around a particular functional ingredient (e.g. stanol-enriched margarines), through to staple everyday foods fortified with a nutrient that would not normally be present to any great extent (e.g. bread or breakfast cereals fortified with folic acid). Functional foods that show promise in postmenopausal health include probiotics, prebiotics, phytosterols and stanols, omega-3 fatty acids, flavonoids and fibre.

The importance of diet is such that the American Heart Association recommends that ‘Women should consume a diet rich in fruits and vegetables; choose wholegrain, high-fibre foods; consume fish, especially oily fish, at least twice a week; limit intake of saturated fat to <10% of energy, and if possible to <7%, cholesterol to <300 mg/day, alcohol intake to no more than 1 drink per day, and sodium intake to <2.3 g/day (approximately 1 tsp salt). Consumption of trans-fatty acids should be as low as possible (e.g. <1% of energy)’ (Mosca et al 2007).

Exercise

Regular physical activity reduces the risk of CHD, osteoporotic fractures and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Hot flushes, urinary incontinence, insomnia and depression may also be helped. A systematic review found that no conclusions regarding the effectiveness of exercise as a treatment for vasomotor menopausal symptoms could be made due to a lack of trials (Daley et al 2007). With regard to CVD, the Nurses Health Study found that low intensity exercise, such as walking, conferred the same benefit as vigorous exercise, and sedentary women who became active late in life reaped similar benefits as those who remained active throughout their life (Manson et al 2002). Exercise has a key role in the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. A Cochrane review found that fast walking improved bone density effectively in the spine and the hip, whereas weight-bearing exercises were associated with increases in bone density of the spine but not the hip (Bonaiuti et al 2003).

Exercise regimens can be very helpful in the management of established osteoporosis, and represent a component of falls prevention programmes. Pelvic floor exercises are used commonly for stress incontinence. They are also used in the treatment of women with mixed incontinence, and less commonly for urge incontinence. Systematic reviews support the view that pelvic floor muscle training and bladder training should be included in first-line conservative management programmes for women with stress, urge or mixed urinary incontinence (Shamliyan et al 2008).

Complementary and alternative medicine

Many women use complementary and alternative medicine in the belief that they are safer and ‘more natural’, especially with concerns regarding the safety of oestrogen-based HRT after publication of the WHI and the MWS. However, evidence from randomized trials for complementary and alternative medicine that improves menopausal symptoms or has the same benefits as HRT is poor (Nedrow et al 2006). Very little well-designed research has been undertaken. The range of approaches used includes botanicals, homeopathy, DHEA, transdermal progesterone creams and mechanical methods (e.g. acupuncture, magnetism).

Botanicals

Phytoestrogens are plant substances that have effects similar to those of oestrogens. Preparations vary from enriched foods, such as bread or drinks (e.g. soy milk), to tablets containing plant extracts. The most important groups are the isoflavones and lignans. The major isoflavones are genistein and daidzein. The major lignans are enterolactone and enterodiol. The role of phytoestrogens has stimulated considerable interest, as people from populations that consume a diet high in isoflavones, such as the Japanese, seem to have lower rates of menopausal vasomotor symptoms; CVD; osteoporosis; and breast, colon, endometrial and ovarian cancers. PHYTOS, ISOHEART and PHYTOPREVENT are European Union studies examining the role of phytoestrogens in osteoporosis, heart disease and cancer. With regard to menopausal symptoms, the evidence from randomized placebo-controlled trials in Western populations is conflicting for soy and derivatives of red clover (Lethaby et al 2007). Similarly, debate also surrounds the effects on lipoproteins, endothelial function, blood pressure, cognition and the endometrium. Endometrial hyperplasia has been reported in soy users. Further well-designed randomized trials are needed to determine the role and safety of phytoestrogen supplements in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women and those who have survived cancer.

Dehydroepiandrosterone

DHEA is a steroid secreted by the adrenal cortex. Blood levels of DHEA decrease dramatically with age. This led to suggestions that the effects of ageing can be counteracted by DHEA ‘replacement therapy’. In the USA, it is classed as a food supplement. No evidence shows that DHEA has any effect on hot flushes (Raven and Hinson 2007). Some studies have shown benefits on the skeleton, cognition, well-being, libido and vagina. The safety of long-term use is, as yet, unknown.

Premature Ovarian Failure

POF is responsible for 4–18% of cases of secondary amenorrhoea and 10–28% of cases of primary amenorrhoea. It is estimated to affect 1% of women under 40 years of age and 0.1% of those under 30 years of age. Although the terms ‘POF’ and ‘premature menopause’ are often used interchangeably, there is debate regarding which term is best. Some women with POF will have oligomenorrhoea, and have persisting sporadic ovarian activity and can become spontaneously pregnant (Nelson et al 2005). In contrast, menopause implies permanent cessation of ovarian activity and menstruation, and infertility. With regard to an age cut-off, premature menopause should ideally be defined as menopause that occurs at an age more than two standard deviations below the mean estimated for the reference population. In the absence of reliable estimates of age of natural menopause in developing countries, the age of 40 years is often used as an arbitrary limit below which the menopause is said to be premature. In the developed world, however, an age of 45 years should be taken as the cut-off point.

Aetiology

Primary premature ovarian failure

Consequences of premature ovarian failure

Women with untreated premature menopause are at increased risk of developing osteoporosis, CVD, cognitive decline, dementia and Parkinsonism, but at lower risk of breast malignancy (Shuster et al 2008). Mean life expectancy in women with menopause before the age of 40 years is 2 years shorter than that in women with menopause after the age of 55 years.

Management

Patients must be provided with adequate information about the condition, its implications on long-term health, use of oestrogen replacement and fertility (Pitkin et al 2007). In those who have not had an oophorectomy, the return of spontaneous ovarian activity and the possibility of spontaneous pregnancy must be explained. While pregnancy may be welcomed by some, this is not true for all women. Women who do not wish to have children need to consider using an effective form of contraception.

Hormone replacement therapy

Oestrogen replacement therapy is the mainstay of treatment for women with POF and is recommended until the average age of natural menopause. This view is endorsed by regulatory bodies. This does not increase the risk of breast cancer to a level greater than that found in normally menstruating women, and women with POF do not need to start mammographic screening early (Ewertz et al 2005). HRT or the combined contraceptive pill may be used. The choice of which to use largely depends on the patient’s age, with the former being more likely to be acceptable to women in their 30s and 40s and the latter being more likely to be acceptable to women in their 20s. There is no evidence to support the efficacy or safety of the use of non-oestrogen-based treatments, such as bisphosphonates, strontium ranelate or raloxifene, in these women. Some patients report reduced libido or sexual function despite apparently adequate doses of oestrogen replacement, especially oophorectomized women, and they may need testosterone addition.

Fertility and contraception

Donor oocyte in-vitro fertilization (IVF) is the treatment of choice for women with primary and secondary POF (Lee et al 2006). In women having chemotherapy or radiotherapy, IVF with embryo freezing prior to treatment currently offers the highest likelihood of a future pregnancy should they experience POF as a result of their treatment. Recent advances in oocyte preservation have improved livebirth rates following freezing of mature eggs. It is still less successful than embryo freezing. Ovulation induction risks delaying treatment. Cryopreservation of ovarian tissue is still largely experimental, although pregnancies have been reported. This technique would be an option for prepubertal girls in whom ovulation induction is not possible.

KEY POINTS

American Cancer Society 2009. Breast Cancer Facts and Figures 2007–2008. Available at http://www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/BCFF-Final.pdf

Archer DF, Hendrix S, Ferenczy A, et al. Tibolone histology of the endometrium and breast endpoints study: design of the trial and endometrial histology at baseline in postmenopausal women. Fertility and Sterility. 2007;88:866-878.

Barber B, Daley S, O’Brien J. Dementia. In: Keith L, Rees M, Mander T, editors. Menopause, Postmenopause and Ageing. RSM Press; 2005:20-34. London

Basson R, Berman J, Burnett A, et al. Report of the international consensus development conference on female sexual dysfunction: definitions and classifications. Journal of Urology. 2000;163:888-893.

Beral V, Million Women Study CollaboratorsBull D, Green J, Reeves G. Ovarian cancer and hormone replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. The Lancet. 2007;369:1703-1710.

Billeci AM, Paciaroni M, Caso V, Agnelli G. Hormone replacement therapy and stroke. Current Vascular Pharmacology. 2008;6:112-123.

Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Gluud L, Simonetti R, Gluud C 2008 Antioxidant supplements for prevention of mortality in healthy participants and patients with various diseases. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2: CD007176.

Bonaiuti D, Shea B, Iovine R et al 2003 Exercise for preventing and treating osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 4: CD0000333.

Burger HG, Hale GE, Dennerstein L, Robertson DM. Cycle and hormone changes during perimenopause: the key role of ovarian function. Menopause. 2008;15:603-612.

Canonico M, Plu-Bureau G, Lowe GD, Scarabin PY. Hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;336:1227-1231. (Clinical Research Ed.)

Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Clinical topic. Menopause. Available at http://cks.library.nhs.uk/menopause

Cummings SR, Ettinger B, Delmas PD, et al. The effects of tibolone in older postmenopausal women. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359:697-708.

Daley A, MacArthur C, Mutrie N, Stokes-Lampard H 2007 Exercise for vasomotor menopausal symptoms. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 4: CD006108.

Elias SG, van Noord PA, Peeters PH, et al. Caloric restriction reduces age at menopause: the effect of the 1944–1945 Dutch famine. Menopause. 2003;10:399-405.

Ewertz M, Mellemkjaer L, Poulsen AH, et al. Hormone use for menopausal symptoms and risk of breast cancer. A Danish cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1293-1297.

Frey BN, Lord C, Soares CN. Depression during menopausal transition: a review of treatment strategies and pathophysiological correlates. Menopause International. 2008;14:123-128.

Gold EB, Bromberger J, Crawford S, et al. Factors associated with age at natural menopause in a multiethnic sample of midlife women. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;153:865-874.

Gosden RG, Treloar SA, Martin NG, et al. Prevalence of premature ovarian failure in monozygotic and dizygotic twins. Human Reproduction. 2007;22:610-615.

Grodstein F, Manron JE, Stampfer MJ. Hormone therapy and coronary heart disease: the role of time since menopause and age at hormone initiation. Journal of Women’s Health. 2006;15:35-44.

Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Johansson H, McCloskey E. FRAX and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporosis International. 2008;19:385-397.

Kenemans P, Bundred NJ, Foidart JM, et al. Safety and efficacy of tibolone in breast-cancer patients with vasomotor symptoms: a double-blind, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncology. 2009;10(2):135-146.

Lee SJ, Schover LR, Partridge AH, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations on fertility preservation in cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:2917-2931.

Lethaby AE, Brown J, Marjoribanks J, Kronenberg F, Roberts H, Eden J 2007 Phytoestrogens for vasomotor menopausal symptoms. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 4: CD001395.

Li CI, Daling JR. Changes in breast cancer incidence rates in the United States by histologic subtype and race/ethnicity, 1995 to 2004. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention. 2007;16:2773-2780.

Lin JT, Lane JM. Nonpharmacologic management of osteoporosis to minimize fracture risk. Nature Clinical Practice Rheumatology. 2008;4:20-25.

Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O’Muircheartaigh CA, Waite LJ. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357:762-774.

Liu B, Beral V, Balkwill A, et al. Gallbladder disease and use of transdermal versus oral hormone replacement therapy in postmenopausal women: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a386. (Clinical Research Ed.)

Manson JE, Greenland P, LaCroiz AZ, et al. Walking compared with vigorous exercise for the prevention of cardiovascular events in women. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347:716-725.

McClung M. Role of RANKL inhibition in osteoporosis. Arthritis Research and Therapy. 2007;9(Suppl 1):S3.

Melby MK, Lock M, Kaufert P. Culture and symptom reporting at menopause. Human Reproduction Update. 2005;11:495-512.

Melville JL, Katon W, Delaney K, Newton K. Urinary incontinence in US women: a population-based study. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2005;165:537-542.

Million Women Study Collaborators. Breast cancer and hormone-replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. The Lancet. 2003;362:419-427.

Mosca L, Banka CL, Benjamin EJ, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women: 2007 update. Circulation. 2007;115:1481-1501.

Nedrow A, Miller J, Walker M, Nygren P, Huffman LH, Nelson HD. Complementary and alternative therapies for the management of menopause-related symptoms: a systematic evidence review. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166:1453-1465.

Nelson LM, Covington SN, Rebar RW. An update: spontaneous premature ovarian failure is not an early menopause. Fertility and Sterility. 2005;83:1327-1332.

Palacios S. The future of the new selective estrogen receptor modulators. Menopause International. 2007;13:27-34.

Parker MJ, Gillespie WJ, Gillespie LD. Effectiveness of hip protectors for preventing hip fractures in elderly people: systematic review. BMJ. 2006;332:571-574. (Clinical Research Ed.)

Perrotta C, Aznar M, Mejia R, Albert X, Ng CW 2008 Oestrogens for preventing recurrent urinary tract infection in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2: CD005131.

Pitkin J, Rees MC, Gray S, et al. Management of premature menopause. Menopause International. 2007;13:44-45.

Population Reference Bureau. Available at http://www.prb.org/pdf07/07WPDS_Eng.pdf, 2007. World Population Data Sheet

Raven PW, Hinson JP. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and the menopause: an update. Menopause International. 2007;13:75-78.

Rees M, Stevenson J. Primary prevention of coronary heart disease in women. Menopause International. 2008;14:40-45.

Reynolds RF, Obermeyer CM. Age at natural menopause in Spain and the United States: results from the DAMES project. American Journal of Human Biology. 2005;17:331-340.

Rossouw JE, Prentice RL, Manson JE, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease by age and years since menopause. JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;297:1465-1477.

Rudkovska I. Functional foods for cardiovascular disease in women. Menopause International. 2008;14:63-69.

Salerno-Kennedy R, Rees M. Diet. In: Rees M, Keith LG, editors. Medical Problems in Women Over 70, when Normative Treatment Plans do not Apply. Abingdon: Informa Healthcare; 2007:199-215.

Shamliyan TA, Kane RL, Wyman J, Wilt TJ. Systematic review: randomized, controlled trials of nonsurgical treatments for urinary incontinence in women. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;148:459-473.

Shapiro S. Recent epidemiological evidence relevant to the clinical management of the menopause. Climacteric. 2007;10(Suppl 2):2-15.

Shuster L, Gostout BS, Grossardt BR, Rocca WA. Prophylactic oophorectomy in pre-menopausal women and long term health — a review. Menopause International. 2008;14:111-116.

Simon JA, Snabes MC. Menopausal hormone therapy for vasomotor symptoms: balancing the risks and benefits with ultra-low doses of estrogen. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 2007;16:2005-2020.

Soules MR, Sherman S, Parrott E, et al. Executive summary: Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW). Fertility and Sterility. 2001;76:874-878.

Tang BM, Eslick GD, Nowson C, Smith C, Bensoussan A. Use of calcium or calcium in combination with vitamin D supplementation to prevent fractures and bone loss in people aged 50 years and older: a meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2007;370:657-666.

Utian WH. The International Menopause Society menopause-related terminology definitions. Climacteric. 1999;2:284-286.

Weiderpass E, Adami HO, Baron JA, et al. Risk of endometrial cancer following estrogen replacement with and without progestins. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1999;91:1131-1137.

Whiteman MK, Staropoli CA, Langenberg PW, McCarter RJ, Kjerulff KH, Flaws JA. Smoking, body mass, and hot flashes in midlife women. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;101:264-272.

Women’s Health Initiative Steering Committee. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291:1701-1712.

World Health Organization. Scientific Group on Research on the Menopause in the 1990s. WHO Technical Report Series 866. WHO, Geneva, 1994.

World Health Organization. Available at http://www.who.int/whosis/database/life_tables/life_tables.cfm, 2006. Life Tables for WHO Member States

Writing Group on Osteoporosis for the British Menopause Society Council. Prevention and treatment of osteoporosis in women. Menopause International. 2007;13:178-181.

Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:321-333.

Writing Group for the British Menopause Society Council. Non-estrogen-based treatments for menopausal symptoms. Menopause International. 2008;14:88-90.