Chapter 47 Meningitis and encephalomyelitis

Infections of the cranial contents can be divided into those which affect the meninges (meningitis) and those which affect the brain parenchyma (encephalitis). Chronic, insidious or rare infections are beyond the scope of this chapter, which will focus on acute bacterial and viral causes of meningitis and encephalomyelitis.

BACTERIAL MENINGITIS

GENERAL POINTS

The bacterial organisms are usually not confined to the brain and meninges and frequently cause systemic illness, for example, severe sepsis, shock, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and bleeding disorders such as disseminated intravascular coagulation.1,2

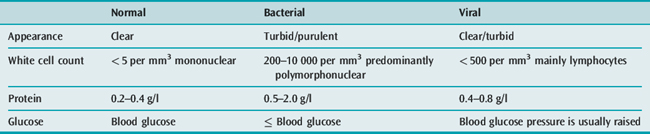

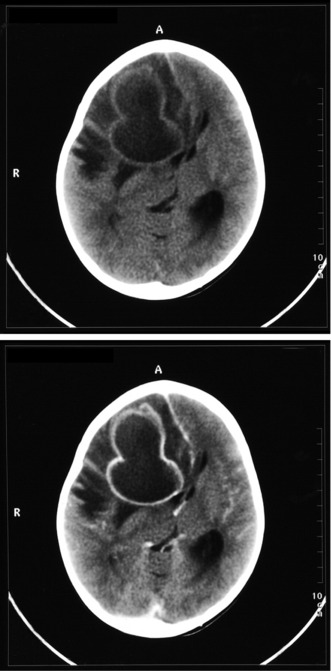

These features raise the possibility of an undiagnosed cerebral mass lesion which, in turn, could cause cerebral herniation if lumbar puncture is performed. A computed tomography (CT) brain scan is required prior to CSF examination in order to explore this possibility and lessen but not obviate the risk of cerebral herniation. Even if the CT brain scan is normal, ICP may still be raised. The importance of performing a safe CSF examination must be balanced against the need to commence immediate treatment in each individual patient.3,4

AETIOLOGY

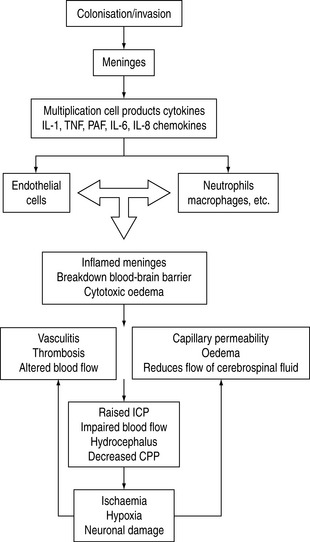

The main causes of meningitis are spread by droplet infection or exchange of saliva. Meningitis may occur when pathogenic organisms colonise the nasopharynx and reach the blood–brain barrier. Meningitis can occur as a result of infection in the middle ear, sinus or teeth, leading to secondary meningeal infection. Most bacteria obtain entry into the CNS via the haematogenous route. As the organisms multiply, they release cell wall products and lipopolysaccharide, and generate a local inflammatory reaction which in itself also releases inflammatory mediators. The net result of the release of cytokines, tumour necrosis factor and other factors is associated with a significant inflammatory response. Vasculitis of CNS vessels, thrombosis, cell damage and exudative material all contribute to vasogenic and cytotoxic oedema, altered blood fiow and cerebral perfusion pressure. Later on infarction and raised ICP occur.5

The inflammatory events seen with infection are summarised in Figure 47.1.

ORGANISMS

Until the advent of the meningitis vaccination programme, H. infiuenzae type B was the most common cause of bacterial meningitis. Recently S. pneumoniae and N. meningitidis have been considered the main causes, although one study suggested that Listeria monocytogenes is the second most common isolate in adult population. The occurrence of pneumococcal strains which are resistant to penicillin has also influenced the epidemiology of meningitis.6

IMMUNOCOMPROMISED HOSTS

In the immunocompromised patient with meningitis (e.g. human immunodeficiency virus: HIV), fungal viral and cryptocococal meningitis should be considered.7

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

It is important to identify from the history reported about preceding trauma, upper respiratory tract infection or ear infection. Symptoms may develop over hours or days. Specific infections relate partly to an individual’s age.

INVESTIGATIONS

The patient with suspected bacterial meningitis requires immediate blood cultures and should be given empirical intravenous (IV) antibiotics if there is likely to be any delay in further assessment (Table 47.1).

MANAGEMENT

Antibiotics should be started as early as possible and broad-spectum coverage is recommended until bacterial identifcation is made (Table 47.2). The selection of antibiotics is influenced by the clinical situation in conjunction with known allergies or local patterns of antibiotic resistance and the CSF findings. Delays in administering antibiotics are a significant risk factor for a poor prognosis. In the absence of a known organism, empirical choice for antibiotics has been complicated by the development of resistant strains. Penicillin G, ampicillin and third-generation cephalosporins are typical first-line agents. Until recently, ampicillin was appropriate for pneumococcal, meningococcal and Listeria infections. The emergence of resistant strains influences local antibiotic practice. If there is a history of recent head injury, a broad-spectrum cephalosporin may be indicated with vancomycin. Discussions with local microbiology services are recommended. If the CSF examination identifies the organism, then specific regimens can be prescribed (Table 47.3).

| Indication | Antibiotic | Dose |

|---|---|---|

| <50 years | Ceftriaxone or cefotaxime | 2–4 g q 24 h 2 g q 4 h |

| >50 years or impaired cell immunity | Ceftriaxone or cefotaxime | 2–4 g q 24 h 2 g q 4 h |

| Cefotaxime + ampicillin or penicillin G | 2 g q 4 h or 3–4 MU q 4 h | |

| Drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae | Ceftriaxone + rifampicin | 2–4 g q 8 h 2 g q 4 h |

| or vancomycin | 0.5 g q 6 h | |

| Neurosurgery shunts trauma | Ceftazidime + nafcillin or | 2 g q 8 h 2 g q 4 h |

| Vancomycin + aminoglycoside | 0.5 g q 6 h 2 mg / kg q 8 h | |

| (gentamicin 5–7 mg/kg stat) |

Table 47.3 General recommendation for known organisms*

| Organism | Antibiotic | Second line or allergy |

|---|---|---|

| Streptococcus pneumoniae (Penicillin-resistant) | Ceftriaxone + vancomycin or rifampicin | Vancomycin + rifampicin |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae (Penicillin-sensitive) | Penicillin G | Ceftriaxone or chloramphenicol |

| β-haemolytic streptococcus | Penicillin or ampicillin | Cefotaxime or chloramphenicol or vancomycin |

| Haemophilus influenzae | Ceftriaxone or cefotaxime | Chloramphenicol |

| Neisseria meningitidis | Penicillin G | Ceftriaxone or chloramphenicol |

| Listeria monocytogenes | Ampicillin + gentamicin | Trimethoprim + sulfamethoxazole |

| Enterobacteriaceae | Ceftriaxone + gentamicin | Quinolones |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Ceftazidime + tobramycin | Quinolones |

* Always check local sensitiviity as resistance patterns are variable.

It is more difficult to select an appropriate empirical antibiotic in the immunocompromised patient. When the organism has been identified and sensitivity results are available, it may be necessary either to change the antibiotic or to rationalise those being given.8

STEROID ADMINISTRATION

The benefit of steroid administration in adult meningitis has been debated. Clear guidance is now available to support its routine use from the Cochrane Database, including 1800 adults and children, which demonstrated a reduction in mortality, hearing loss and neurological complications. Some concerns remain, including the possibility that dexamethasone may adversely affect CSF penetration or cause longer-term cognitive problems.9 A longer and more established literature exists for the use of steroids in bacterial meningitis in children. These studies confirm a benefit for those with Haemophilus infiuenzae type B infection and reduce the frequency of postmeningitis deafness.

RECOMMENDATIONS IN ADULTS

ANTICONVULSANTS

Focal or generalised seizures should be treated immediately with IV benzodiazepines to stop the seizures and the individual should then subsequently be loaded with IV phenytoin. The possibility of the following should be considered:

The development of seizures may be indicative of a poor prognosis.

GENERAL MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS10

RESPIRATORY SUPPORT

It is important to secure the airway and respiratory support may be required for those with severe shock or profound coma. Attention should be paid to management of the unconscious patient with appropriate mouth and eye care. Physiotherapy will be required in order to prevent the onset of pressure sores. Surgical evaluation may be needed for skin necrosis.11,12

PROGNOSIS

Untreated, bacterial meningitis is usually fatal. Appropriate therapy significantly reduces the mortality rate; however, recent studies still show that the overall mortality is approximately 18%. Mortality is slightly higher in those who have seizures and when there have been delays introducing treatment, or if the patient is elderly or very young12,13 (see Table 47.3).

VIRAL MENINGITIS

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Patients usually present with symptoms of meningeal irritation, fever, headache, neck stiffness, retrobulbar pain, photophobia, vertigo, nausea and vomiting which are less severe than those with bacterial meningitis. The presence of intellectual impairment, focal neurological symptoms or seizures suggests that the brain parenchyma is involved and, consequently, these are due to meningoencephalitis. True viral meningitis develops over hours to days but rarely lasts longer than 7–10 days. A variety of associated symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting and generalised malaise, may accompany this condition.14

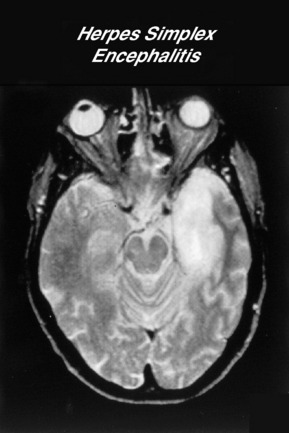

ENCEPHALITIS

Encephalitis is a viral infection of the brain. HSV 1 is the most common and serious cause of focal encephalitis, which usually affects the temporal and frontal lobes. There are a large number of arboviruses that cause epidemics of encephalitis. These are usually borne by arthropod vectors, such as mosquitoes and ticks, and therefore are considered as airborne viruses.15 West Nile virus is now the most common cause of epidemic viral encephalitis in some countries. Neuroimaging changes in basal ganglia may suggest the diagnosis but the CSF pleopcytosis may have a predominance. Specific CSF antibodies can be sent for West Nile virus.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

TREATMENT

Specific treatment for HSV encephalitis requires IV aciclovir at a dose of 30 mg/kg per day for 14 days. Left untreated, the mortality of HSV encephalitis is approximately 70% but there is still a 25% mortality in patients treated with optimal therapy. Patients can be left with significant disability in terms of cognitive dysfunction or seizures. Most patients with significant cerebral oedema receive empirical steroids, although there are no clinical trials to support this therapy. Aciclovir can cause renal impairment and the patient should be hydrated intravenously and renal function monitored.16 Aggressive treatment of seizures is important.

TUBERCULOUS MENINGITIS

Tuberculous meningitis has a variable natural history with a range of different clinical presentations. This and the lack of specific and sensitive tests hinders the diagnosis of this condition. Approximately 10% of individuals with tuberculosis develop meningeal involvement. A variety of risk factors, such as HIV, diabetes mellitus and recent steroid use, may increase the risk of tuberculous meningitis.17

CLINICAL FEATURES

Tuberculous meningitis has a very varied clinical presentation. Often, it is heralded by a non-specific prodromal phase, frequently but not necessarily including headache, vomiting and fever. Of one case series which included those admitted to an intensive care unit, only 65% had fever, 52% had focal neurology and 88% had signs of meningism. A variety of cranial nerve palsies can occur but other presentations include those seen with stroke, hydrocephalus and tuberculoma.

DIAGNOSIS

An investigation of the differential diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis is important. PCR amplification of mycobacterial DNA has not been fully evaluated in this technique which, in the case of tuberculous meningitis, usually requires a lumbar puncture examination. Those who are immunosuppressed may have atypical CSF appearance, including normal CSF examinations in occasional HIV individuals. Tuberculosis culture from CSF is required but may take up to 6 weeks before a positive culture result is available. Imaging studies may show a basal meningitis and hydrocephalus but these features are non-specific.18

Current advice suggests that the first 2 months of treatment should comprise quadruple therapy:

There is increasing multidrug-resistant tuberculous meningitis, especially in the HIV-positive population, and so sensitivity is important. Some clinical trials suggest that steroids have a beneficial effect in some groups of patients.19 Patients may require neurosurgical intervention for the treatment of hydrocephalus.

EPIDURAL INFECTION

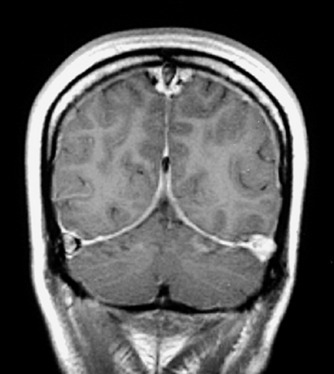

CEREBRAL VENOUS AND SAGITTAL SINUS THROMBOSIS

Venous and sinus thrombosis may occur in the context of infection; in particular meningitis, and epidural or subdural abscess. It may also be secondary to facial or dental infection. It may have no septic aetiology but can occur either as an isolated event or in association with prothrombotic problems such as diabetic ketoacidosis, methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) abuse (ectsasy), oral contraceptives and hereditary prothrombotic conditions in pregnancy.20

Clinical signs at presentation include:

The diagnostic sensitivities of CT, MRI and digital subtract angiography are 59%, 86% and 100%, respectively, but MRI with magnetic resonance angiography reaches 96% (Figure 47.3).

BRAIN ABSCESS

LYME DISEASE

This is a tickborne multisystem disease with dermatological, cardiological, rheumatological and neurological effects caused by the spirochaete Borrelia burgdorferi.

Lyme disease usually presents as an acute febrile illness with gastrointestinal upset, but it may present in a variable fashion neurologically, including as a cranial neuropathy (commonly a facial palsy) or as a meningoencephalitis or radiculopathy. It may also cause a lymphocytic meningitis and may have been diagnosed as a ‘viral’ meningitis in the past. A variety of longer-term neurological sequelae have been described.22

TREATMENT

β-lactam antibacterials, such as penicillin V, amoxicillin and cefuroxime, are effective first-line treatment. The optimal duration of treatment is not known, but 10–21 days is recommended.23,24 Practice parameters for the treatment of nervous system Lyme disease state that nervous system infection responds favourably to penicillin, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime and doxycycline. Prolonged treatment with antibiotic appears to have no benefit in preventing post-Lyme syndrome.

OTHER DISEASES

Septic encephalopathy has been described as a common complication in the critically ill, presenting in a panoply of ways, from the agitated confused state seen in acute sepsis through to profound loss of consciousness. The aetiology is almost certainly multifactorial, involving changes in cerebral blood flow, alteration in oxygen extraction, cerebral oedema, disruption of the blood–brain barrier, the presence and effects of diverse inflammatory mediators and abnormal neurotransmitter activity. Deranged liver and renal function contribute. It is a syndrome of exclusion based on observation and circumstantial evidence. The EEG is usually abnormal with decreased fast activity and an increase of slow-wave activity, but the findings are not pathognomonic. There are no specific treatments. In general terms, outcome appears to correlate with the management of the underlying sepsis.25

1 Isenberg H. Bacterial meningitis: signs and symptoms. Antibiot Chemother. 1992;45:79-95.

2 Spach DH, Jackson LA. Bacterial meningitis. Neurol Clin. 1999;17:711-735.

3 Roos KL. Acute bacterial meningitis. Semin Neurol. 2000;20:293-306.

4 Anderson M. Management of cerebral infection. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1993;56:1243-1258.

5 Pfister HW, Fontana A, Tauber MG, et al. Mechanisms of brain injury in bacterial meningitis: workshop summary. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:463-479.

6 van Deuren M, Brandtzaeg P, van der Meer JW. Update on meningococcal disease with emphasis on pathogenesis and clinical management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:144-166.

7 Gottfredsson M, Perfect JR. Fungal meningitis. Semin Neurol. 2000;20:307-322.

8 Vandecasteele SJ, Knockaert D, Verhaegen J, et al. The antibiotic and anti-inflammatory treatment of bacterial meningitis in adults: do we have to change our strategies in an era of increasing antibiotic resistance? Acta Clin Belg. 2001;56:225-233.

9 Van de Beek D, de Gans J, McIntyre P, et al. Corticosteroids for acute bacterial meninigitis (review). Cochrane Collaboration. 2007.

10 Raser K, Deziel PJ. The danger of bacterial meningitis in the adult. JAAPA. 2001;14:16-18. 21–4

11 Hussein AS, Shafran SD. Acute bacterial meningitis in adults. A 12-year review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2000;79:360-368.

12 Durand ML, Calderwood SB, Weber DJ, et al. Acute bacterial meningitis in adults. A review of 493 episodes. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:21-28.

13 Pfister HW, Feiden W, Einhaupl KM. Spectrum of complications during bacterial meningitis in adults. Results of a prospective clinical study. Arch Neurol. 1993;50:575-581.

14 Robert HA. Viral meningitis. Semin Neurol. 2000;20:277-292.

15 Schmutzhard E. Viral infections of the CNS with special emphasis on herpes simplex infections. J Neurol. 2001;248:469-477.

16 Gutierrez KM, Prober CG. Encephalitis. Identifying the specific cause is key to effective management. Postgrad Med. 1998;103:123-125. 129–30, 140–3

17 Thwaites G, Chau TT, Mai NT, et al. Tuberculous meningitis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68:289-299.

18 Roos KL. Mycobacterium tuberculosis meningitis and other etiologies of the aseptic meningitis syndrome. Semin Neurol. 2000;20:329-335.

19 Prasad K, Volmink J, Menon GR. Steroids for treating tuberculous meningitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;3:Cd002244.

20 de Bruijn SF, Stam J, Koopman MM, et al. Case-control study of risk of cerebral sinus thrombosis in oral contraceptive users and in carriers of hereditary prothrombotic conditions. The Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis Study Group. Br Med J. 1998;316:589-592.

21 Yildizhan A, Pasaoglu A, Ozkul MH, et al. Clinical analysis and results of operative treatment of 41 brain abscesses. Neurosurg Rev. 1991;14:279-282.

22 Halperin JJ, Shapiro D, Logigia N, et al. Practice parameter: treatment of nervous system Lyme disease: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2007;69:91-102.

23 van Dam AP. Recent advances in the diagnosis of Lyme disease. Exp Rev Mol Diagn. 2001;1:413-427.

24 Glaser C, Lewis P, Wong S. Pet-, animal-, and vector-borne infections. Pediatr Rev. 2000;21:219-232.

25 Papadopoulos MC, Davies DC, Moss RF, et al. Pathophysiology of septic encephalopathy: a review. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3019-3024.