Melanocytic neoplasms

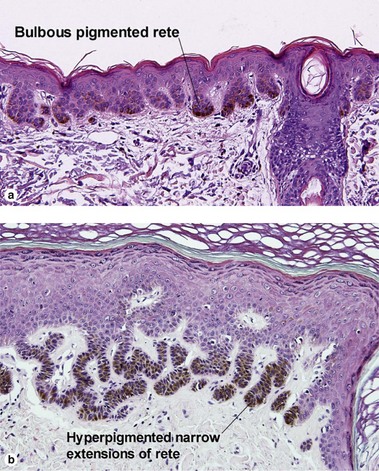

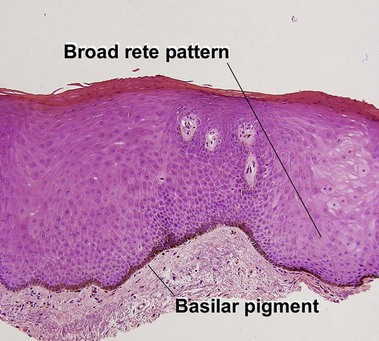

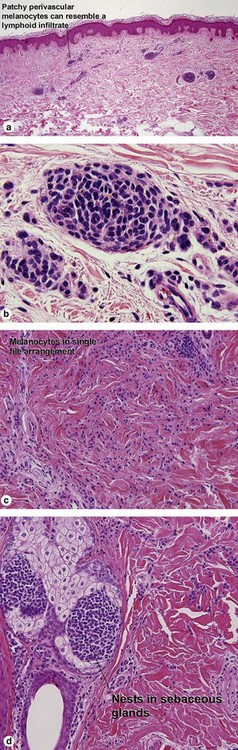

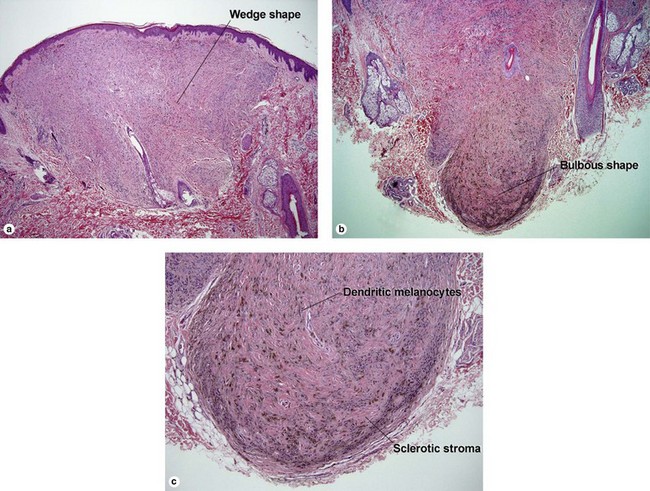

Benign melanocytic nevus

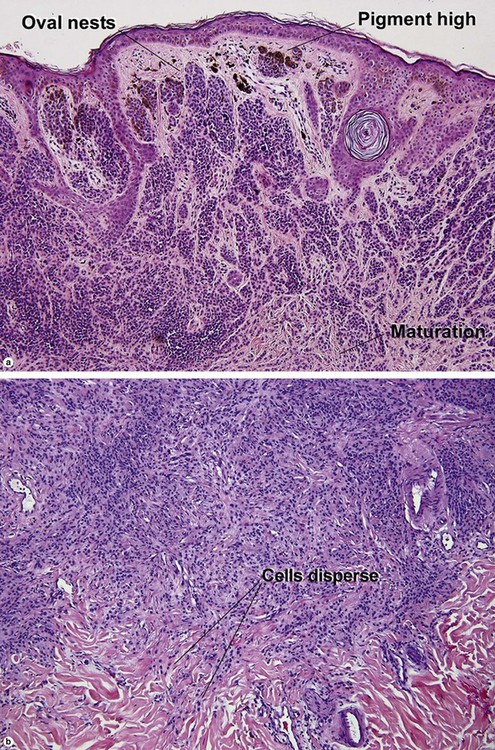

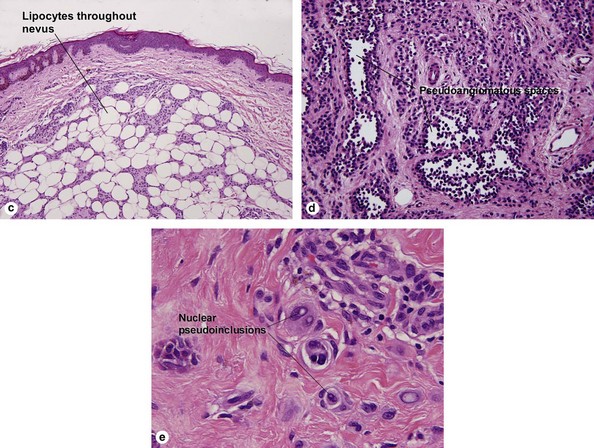

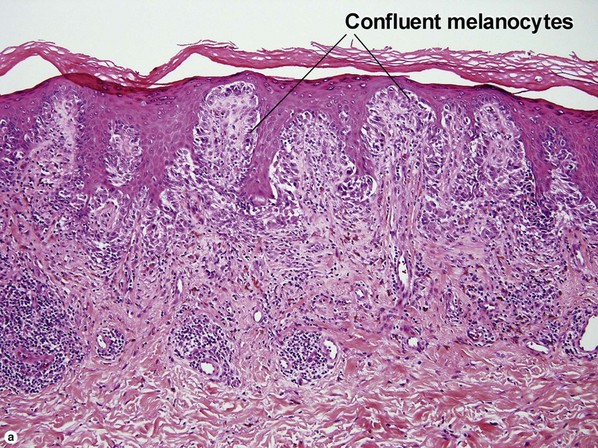

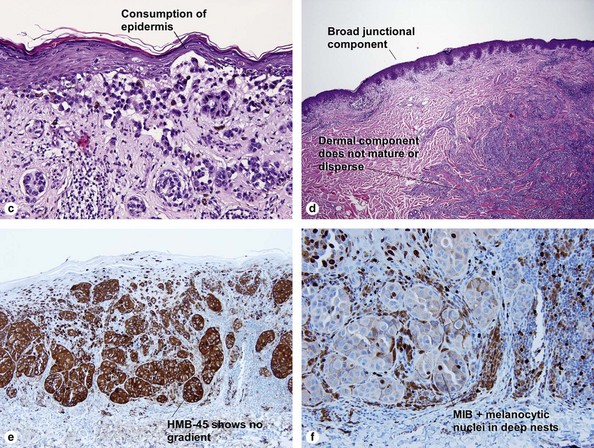

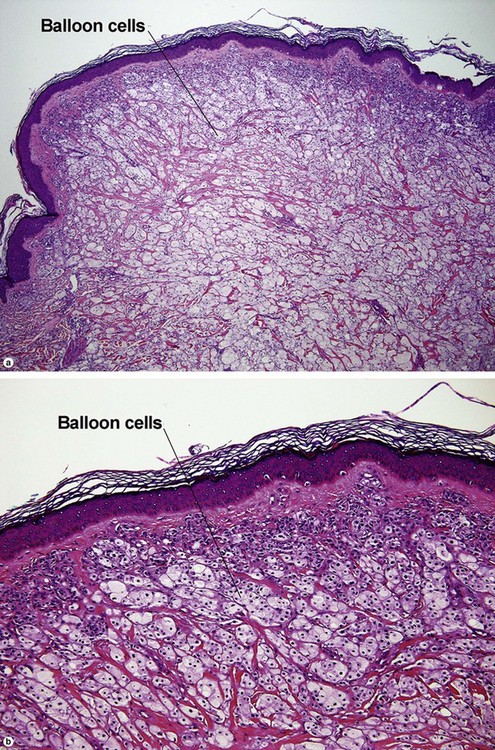

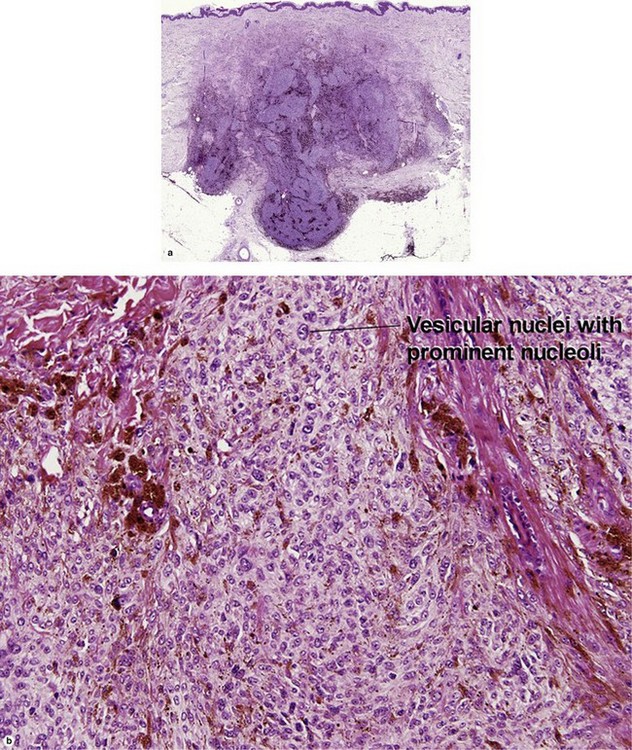

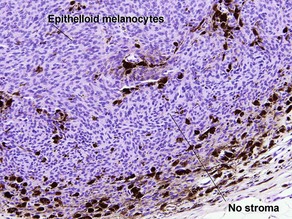

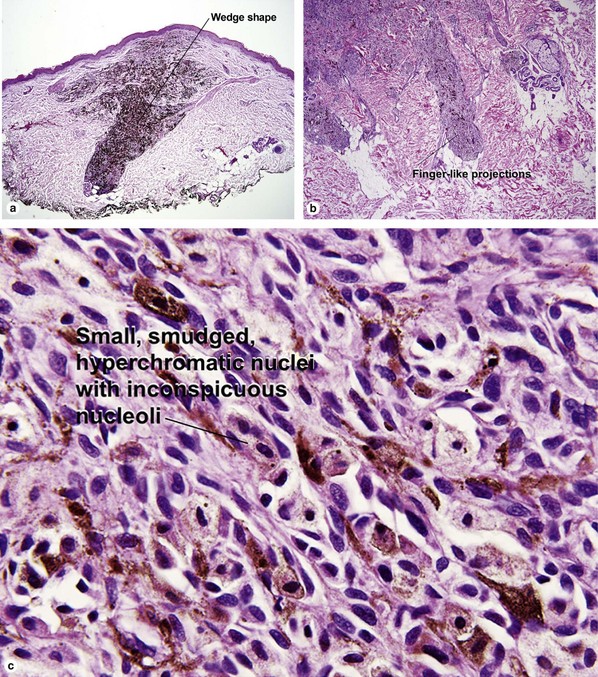

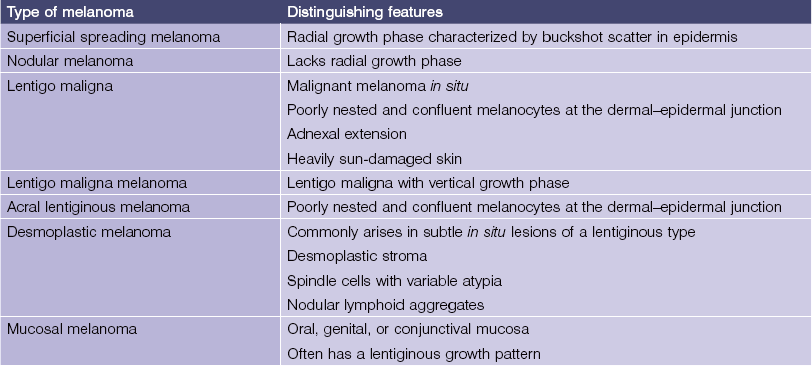

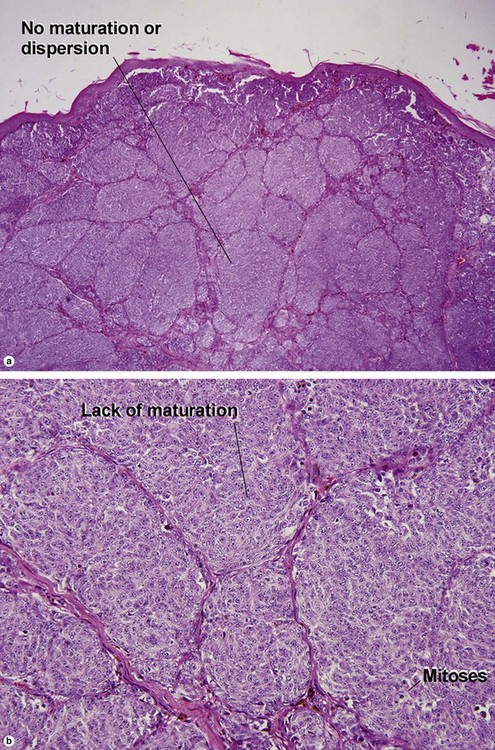

Table 6.1 gives general rules, and is a good starting point for the evaluation of pigmented lesions. There are exceptions to the rules. For example, blue nevi show no evidence of maturation or dispersion. They are commonly deeply pigmented to the base of the lesion. They are readily recognized by their wedge-like or bulbous outline and characteristic cytologic features.Table 6-1

Characteristics of nevus versus melanoma

| Characteristic | Nevus | Melanoma |

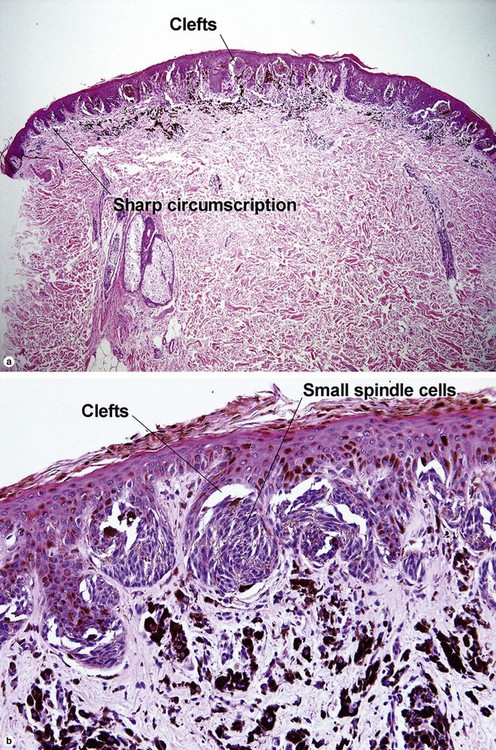

| Lateral circumscription | Sharp | Variable |

| Bilateral (right to left) symmetry | Yes | Commonly asymmetrical |

| Top to bottom symmetry | No | Variable |

| Size | Small | Usually quite broad |

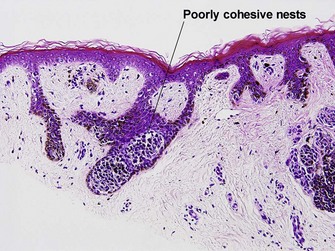

| Dermal–epidermal junction | Well nested | Non-nested melanocytes usually outnumber nests in areas |

| Shape of junctional nests | Round to oval | Often elongated and bizarre |

| Location of junctional nests | Tips and sides of rete | Tops of dermal papillae often involved as well |

| Spacing of junctional nests | Regular | Usually irregular |

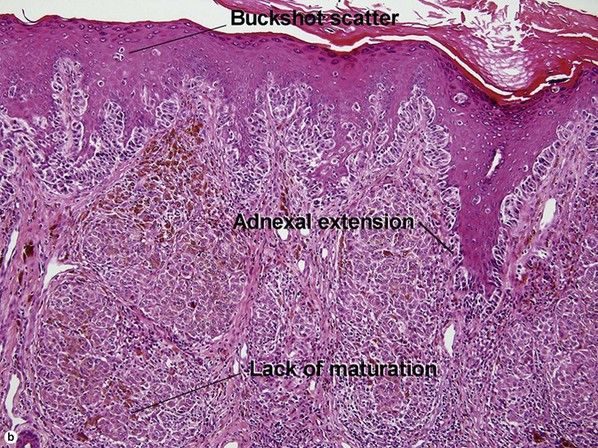

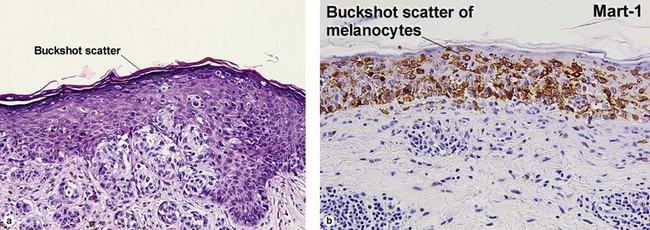

| Buckshot scatter in epidermis | Absent except in the center of Spitz nevi, pigmented spindle cell nevi, acral nevi, traumatized nevi, and sunburned nevi | Variable (present in superficial spreading malignant melanoma, usually not prominent in lentigo maligna and acral lentiginous malignant melanoma) |

| Maturation | Cells become smaller and more neuroid from top to bottom | Typically fails to mature |

| Dispersion | Disperses to single units at base of lesion | Generally remains nested at base |

| Junctional vs dermal nests | Dermal nests smaller than junctional nests; from top to bottom, nests become smaller, melanocytes disperse | Dermal nests often larger than junctional nests |

| Deep mitoses | Rare | Variable |

| Deep pigment | No | Variable |

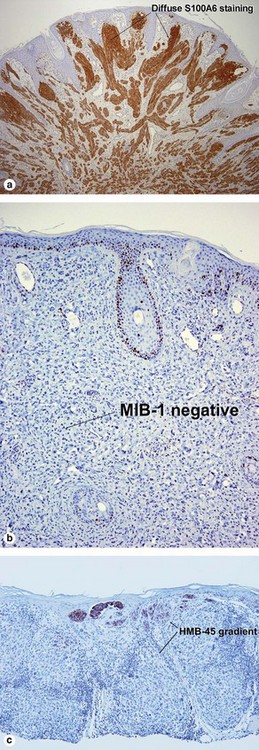

| HMB-45 | Top-heavy | Commonly stains strongly to base |

| MIB-1 | No deep nuclei positive | Deep nuclei commonly positive |

| S100A6 | Spitz nevi usually stain diffusely | Usually patchy |

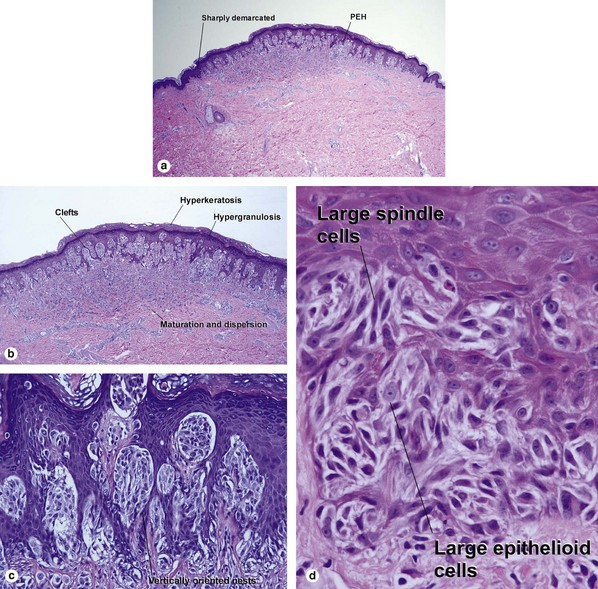

Pigmented spindle cell nevus of Reed

Table 6-2

Characteristics of Spitz nevus versus pigmented spindle cell nevus of Reed

| Characteristic | Spitz nevus | Pigmented spindle cell nevus of Reed |

| Age | Children | Young women |

| Color | Usually pink | Usually dark brown |

| Location | Head | Legs |

| Hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia | Yes | Yes |

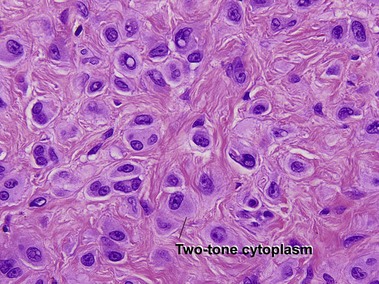

| Cytology | Large spindle and epithelioid cells | Small spindle cells |

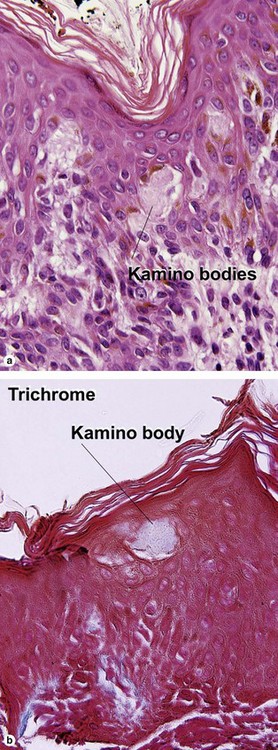

| Kamino bodies | Common | Variable |

| Buckshot scatter in epidermis | Normal in center lesion | Normal in center lesion |

| S100A6 | Strongly + | Weak and patchy |

Acral nevus

Within the central portion of an acral nevus, melanocytes are commonly noted above the dermal–epidermal junction. As long as it is confined to the center of the lesion, “buckshot scatter” by itself is not a worrisome feature in an acral nevus.

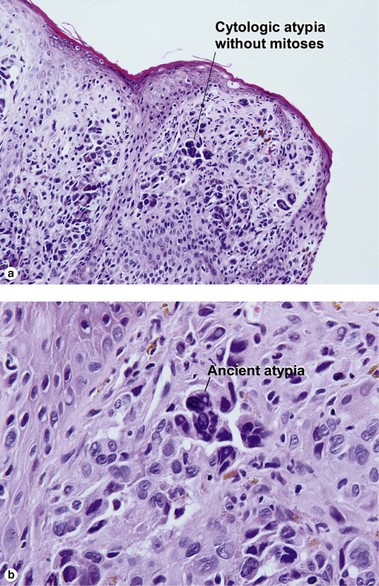

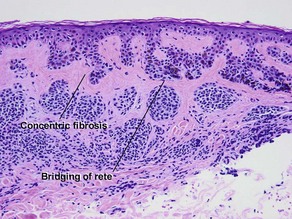

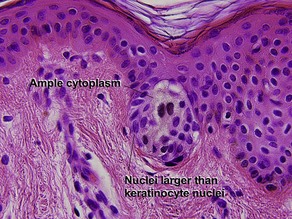

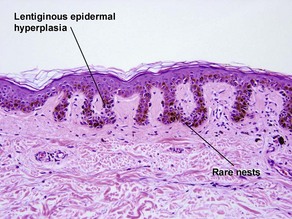

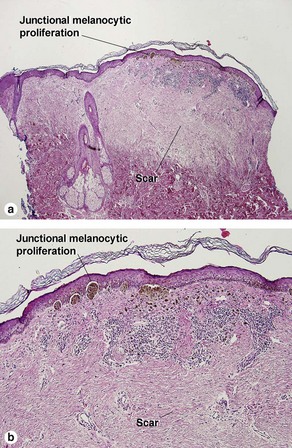

Dysplastic nevus

Grading dysplastic nevi

• Low-grade: atypia restricted to shoulder region

• Moderate: atypia in both shoulder region and central portion, some irregularity and confluence of nests

• High-grade: high-grade cytologic atypia in areas, not entirely well nested at junction, irregular nests, may be marginal in distinction from malignant melanoma in situ

Some have questioned the significance of grading of dysplastic nevi. Others prefer to divide them into high-grade and low-grade lesions.

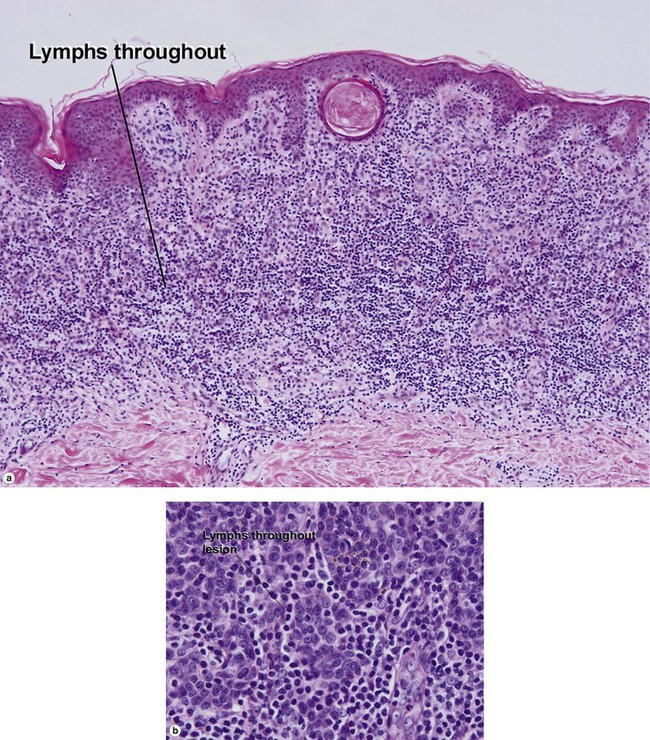

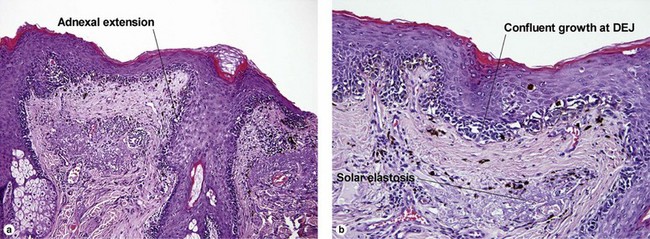

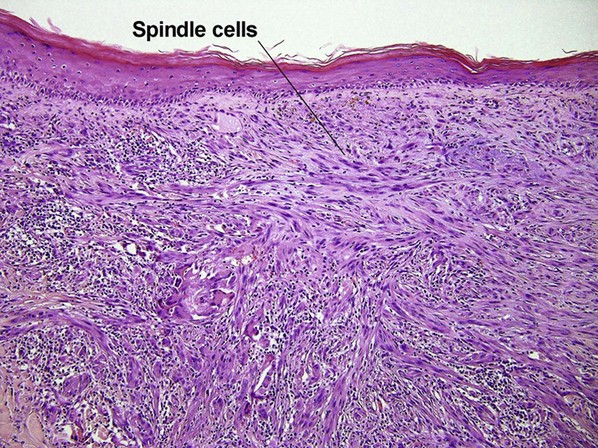

Superficial spreading malignant melanoma

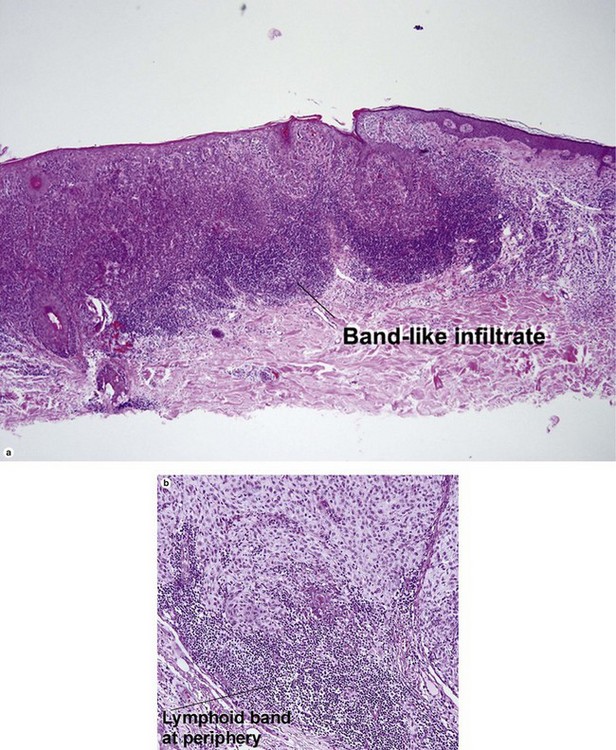

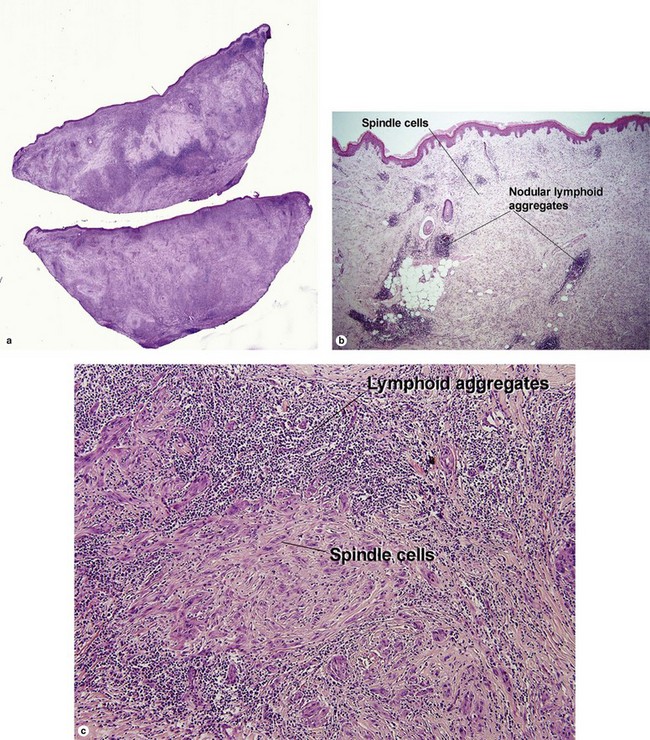

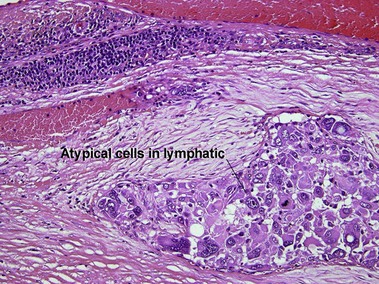

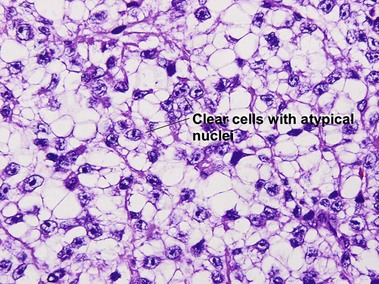

Metastatic melanoma

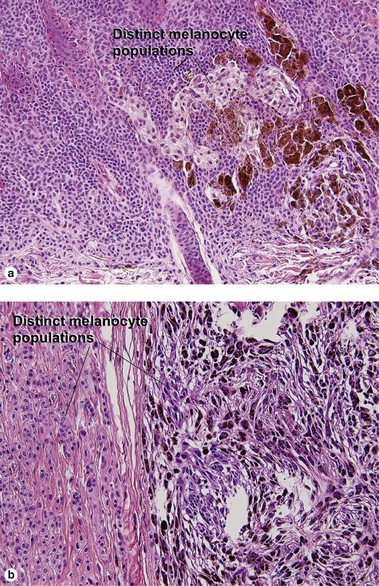

Epidermotropic nevoid metastases typically fail to mature or disperse well at the base. This helps to distinguish them from nevi. In lymph nodes, metastatic melanoma is typically subcapsular in location. Nodal nevi occur, but are typically located within the capsule and are composed of bland nuclei.

Bauer, J, Bastian, BC. Distinguishing melanocytic nevi from melanoma by DNA copy number changes: comparative genomic hybridization as a research and diagnostic tool. Dermatol Ther. 2006; 19(1):40–49.

Boyd, AS, Rapini, RP. Acral melanocytic neoplasms: a histologic analysis of 158 lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994; 31(5 Pt 1):740–745.

Cerroni, L. A new perspective for spitz tumors? Am J Dermatopathol. 2005; 27(4):366–367.

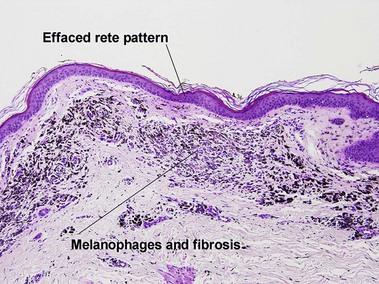

Cesinaro, AM. Clinico-pathological impact of fibroplasia in melanocytic nevi: a critical revision of 209 cases. APMIS. 2012; 120(8):658–665.

Dalton, SR, Gardner, TL, Libow, LF, et al. Contiguous lesions in lentigo maligna. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005; 52(5):859–862.

Farrahi, F, Egbert, BM, Swetter, SM. Histologic similarities between lentigo maligna and dysplastic nevus: importance of clinicopathologic distinction. J Cutan Pathol. 2005; 32(6):405–412.

Ferrara, G, Argenziano, G, Soyer, HP, et al. The spectrum of Spitz nevi: a clinicopathologic study of 83 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2005; 141(11):1381–1387.

Griewank, KG, Ugurel, S, Schadendorf, D, et al. New developments in biomarkers for melanoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2013; 25(2):145–151.

Kapur, P, Selim, MA, Roy, LC, et al. Spitz nevi and atypical Spitz nevi/tumors: a histologic and immunohistochemical analysis. Mod Pathol. 2005; 18(2):197–204.

King, R, Page, RN, Googe, PB, et al. Lentiginous melanoma: a histologic pattern of melanoma to be distinguished from lentiginous nevus. Mod Pathol. 2005; 18(10):1397–1401.

Moore, DA, Pringle, JH, Saldanha, GS. Prognostic tissue markers in melanoma. Histopathology. 2012; 60(5):679–689.

Nambiar, S, Mirmohammadsadegh, A, Hengge, UR. Cutaneous melanoma: fishing with chips. Curr Mol Med. 2008; 8(3):235–243.

Ribé, A, McNutt, NS. S100A6 protein expression is different in Spitz nevi and melanomas. Mod Pathol. 2003; 16(5):505–511.

Strungs, I. Common and uncommon variants of melanocytic naevi. Pathology. 2004; 36(5):396–403.

Tannous, ZS, Mihm, MC, Jr., Sober, AJ, et al. Congenital melanocytic nevi: clinical and histopathologic features, risk of melanoma, and clinical management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005; 52(2):197–203.

Urso, C. A new perspective for spitz tumors? Am J Dermatopathol. 2005; 27(4):364–366.

Xu, X, Elder, DE. A practical approach to selected problematic melanocytic lesions. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004; 121.