41 Medication-Induced Movement Disorders

There are a large number of pharmaceutical agents with the potential to cause a movement disorder (Table 41-1). These medications primarily interfere with dopaminergic transmission within the basal ganglia (levodopa, dopamine agonists, dopamine receptor–blocking agents [DRBs]). Other classes of these movement disorder–inducing agents do not have as precisely defined biochemical mechanisms. These medications include central nervous system (CNS) stimulants, anticonvulsants, tricyclic antidepressants, and estrogens. From a clinical perspective, the medications most commonly responsible for iatrogenic movement disorders are the various neuroleptics and pharmacologic agents that block or stimulate dopamine receptors.

Table 41-1 Types of Drug-Induced Movement Disorders and Responsible Medications

| Syndrome | Responsible Medication |

|---|---|

| Postural tremor | |

| Acute dystonic reactions | |

| Akathisia | |

| Parkinsonism | |

| Chorea, including tardive and orofacial dyskinesia | |

| Dystonia, including tardive dystonia (excluding acute dystonic reactions) | |

| Neuroleptic malignant syndrome | |

| Tics | |

| Myoclonus | |

| Asterixis |

Clinical Syndromes

Acute Dystonic Reactions

These very dramatic movement disorder syndromes usually develop within 5 days after initiation of various neuroleptic medications. This clinical picture typically presents very rapidly after initiation of the responsible therapeutic agent. The craniocervical region is the most commonly affected site. These patients are sometimes thought to have tetanus what with the facial spasms mimicking the classic trismus with risus sardonicus (Fig. 41-1).

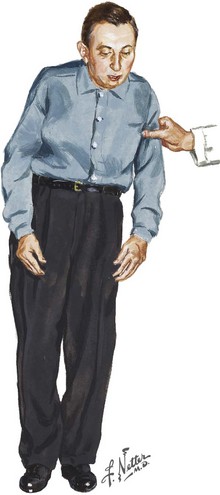

Medication-Induced Parkinsonism

Various medications have the potential to interfere with the synthesis, storage, and release of dopamine, as well as the varied dopamine-blocking agents, and may precipitate an akinetic-rigid syndrome that is nearly indistinguishable from idiopathic Parkinson disease (Fig. 41-2). Substituted benzamides, particularly metoclopramide, used to treat gastrointestinal disorders, and calcium channel blockers particularly have the potential to produce a medication-induced parkinsonism. The basic pathophysiologic mechanism here is related to a predominant presynaptic effect on dopamine and serotonin neurons.

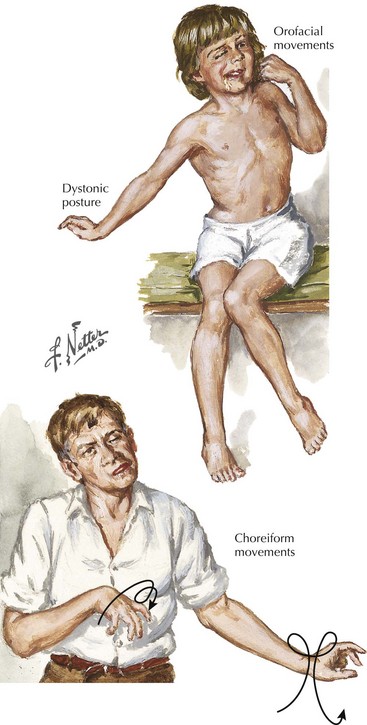

Tardive Dyskinesia Syndromes

Most commonly, TD clinically affects the orofacial region, in particular, various chewing movements, tongue protrusion, vermicular tongue motion, lip smacking, puckering, and pursing (Fig. 41-3A). TD patients also have hyperkinesias, including chorea (Fig. 41-3B), athetosis, dystonia, and tics affecting the limb and truncal regions, or paroxysms of rapid eye blinking. Various risk factors are thought to be operative, including female sex, older age, and duration and dosage of therapy. It may take months for TD to resolve if they are going to do so, and sadly this is not predictable.

Esper CD, Factor SA. Failure of recognition of drug- induced parkinsonism in the elderly. Mov Disord. 2008 Feb 15;23(3):401-404.

Gershanik OS. Drug-induced dyskinesia. In: Anodic J, Tolosa E, editors. Parkinson’s disease and movement disorders. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1998:579-600.

Kiriakakis V, Bhatia K, Quinn NP, et al. The natural history of tardive dystonia: a long-term follow-up study of 107 cases. Brain. 1998;121:2053-2066.

Mena MA, de Yebenes JG. Drug-induced parkinsonism. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2006 Nov;5(6):759-771.

Pierre JM. Extrapyramidal symptoms with atypical antipsychotics; incidence, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 2005;28(3):191-208.

Woerner MG, Alvir JMJ, Saltz BL, et al. Prospective study of tardive dyskinesia in the elderly: rates and risk factors. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1521-1528.