Measurement and Documentation

Measurement and documentation are critical components in the process of providing patient care. Measurements (numerical or categorical assignments based on testing or measuring) form the basis for deciding intervention strategy and therefore influence patient response to therapeutic interventions.1 Measurements are also used during treatment sessions to determine rate of progression and appropriateness of exercise prescriptions. Typically, therapists obtain a series of measures and, in combination with those made by other health care professionals, formulate a clinical hypothesis. The hypothesis includes both physical and psychosocial aspects. If parts of the hypothesis are incorrect because of inaccurate measures, interventions may be misdirected, which can result in treatment that is either not effective or unsafe. Consequently, knowledge of the qualities of measurements that relate to the cardiovascular and pulmonary systems is essential for effective patient care.

Characteristics of Measurements and Outcomes

Levels or Types of Measurements

Measurements can be described according to their type or level of measurement. There are four levels of measurements: nominal, ordinal, interval, and ratio (Table 7-1).2 Recognizing the level of measurement aids understanding and interpretation of the result.

Table 7-1

Examples of Commonly Used Measurements and Their Respective Level of Measurement

| Patient Characteristic | Test or Other Measure | Level of Measurement |

| Gender | Male/female | Nominal |

| Range of motion | Goniometry | Ratio |

| Muscle strength | Manual muscle testing (MMT) | Ordinal |

| Isokinetic dynamometry | Interval | |

| Functional status | Functional independence measure | Ordinal |

| Timed Up and Go (TUG) | Ratio | |

| Angina | Angina rating scale | Ordinal |

| Borg CR10 | Ratio | |

| Dyspnea | MRC scale | Ordinal |

| Borg CR10 | Ratio | |

| Visual Analog Scale | Ratio |

Nominal

The categories of a nominal measurement scale are defined using objective indicators that are universally understood. For example, the classification of patients with heart failure could be based on the primary cause for the development of the condition (Box 7-1). In each case, the cause would be determined by diagnostic testing such as angiography or echocardiography. Clear descriptions of the criteria for inclusion in each category are necessary to facilitate clinicians’ agreement on the assignment of patients to categories. A high percentage of agreement indicates high interrater reliability.

Ordinal

Ordinal measurements are similar to nominal measurements with the exception that the categories are ordered or ranked. The categories in an ordinal scale indicate more or less of a certain attribute. The scale for rating angina is an example of an ordinal scale (Table 7-2). Each category is defined, and a rating of grade 1 angina is less than a rating of grade 4. In an ordinal scale, the differences between consecutive ratings are not necessarily equal. The difference between grade 1 angina and grade 2 is not necessarily the same as between grade 3 and grade 4 angina. Consequently, if numbers are assigned to categories, they can be used to represent rank but cannot be subjected to mathematical operations. Averaging angina scores is incorrect because averaging assumes that there are equal intervals between categories. A group of ordinal data could be reported as a percentage of each response (i.e., 80% of clients reported exercise-induced angina as 3 before a cardiac rehabilitation program.)

Table 7-2

| Rating | Description |

| 1 | Mild, barely noticeable |

| 2 | Moderate, bothersome |

| 3 | Moderately severe, very uncomfortable |

| 4 | Most severe or intense pain ever experienced |

From American College of Sports Medicine: ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Philadelphia, 2010, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Categorical measurements are considered ordinal if being assigned to a specific category is considered better than or worse than being in another category. For example, patients with angina could be classified as having either stable or unstable angina. This measurement would be considered ordinal, because stable angina is considered a better condition to have compared with unstable angina.3

Ratio

Ratio measurements have scales with units that are equal in size and have a zero point that indicates absence of the attribute being measured. Examples of ratio measurements that are used in cardiopulmonary physical therapy include heart rate, cardiac output, oxygen consumption, and 6-minute walk distance (6-MWD). Ratio measurements are always positive values and can be subjected to all arithmetic operations. For example, an aerobic capacity of 4 L/min is twice as great as an aerobic capacity of 2 L/min. The Borg CR10 scale and visual analogue scales are also examples of ratio level measurements.4,5 The zero point of these scales is “nothing at all” or no perception of exertion. The CR10 scale may be preferable for use with patients who experience strong symptoms during testing or training.6

Reliability and Validity of Measurements

For a measurement to be of value to the therapist, the measure should be both reliable (reproducible) and valid (meaningful). When selecting and performing tests and measures, it is important to remember that measures can be reliable but not valid for a specific application.7

Reliability

A third factor contributing to measurement variability is the difference in the methods therapists use to obtain measurements. If a measurement is consistent when the same therapist repeats a test, then the measurement is said to have high intrarater reliability. Measurements that are consistent when multiple therapists perform the test under the same conditions are said to have high interrater reliability. Often, measurements have high intrarater reliability but lower interrater reliability because of variations in the specific methods used by therapists to attain the same measurement. Auscultation of breath sounds, a commonly used method of assessing patients in cardiopulmonary settings, has been shown to have only poor to fair interrater reliability.8 Interrater reliability is important in clinical settings in which a patient may be evaluated and treated by more than one therapist. If the interrater reliability of a measurement is low, changes in the patient over time may not be accurately reflected. Interrater reliability for auscultation of breath sounds can be improved through education of the persons performing the measurements.8

Validity

Valid measurements are those that provide meaningful information and accurately reflect the characteristic for which the measure is intended. For a measure to be useful in a clinical setting, it must possess a certain degree of validity. Measurements can be reliable but not valid. For example, the ankle-brachial index (ABI) is reliable but not necessarily valid in all populations.9

There are various types of validity. Of importance in clinical practice are concurrent, predictive, and prescriptive validity. Concurrent validity is when a measurement accurately reflects measurements made with an accepted standard. Comparing a measurement made with a heart rate monitor with an ECG recording is an example of determining concurrent validity. In this example, the ECG recording would be considered the gold or accepted standard. Another example is using pulse oximetry during exercise testing. Yamaya and colleagues (2002)10 compared pulse oximetry versus directly measured arterial oxygen saturation (the gold standard) and reported that a forehead sensor was more valid than a finger sensor. Measurements with predictive validity can be used to estimate the probability of occurrence of a future event. Screening tests often involve measurements that are used to predict future events. For example, identifying people with risk factors for coronary artery disease (CAD) leads to a prediction that their likelihood of developing CAD is higher than normal. Measures with prescriptive validity provide guidance to the direction of treatment. The categorical measurement of determining a person’s risk for a future coronary event is a measurement that would need to have prescriptive validity. By classifying patients into high- versus low-risk categories on the basis of results of a diagnostic exercise test, the intensity and rate of progression of treatment is determined.

Sensitivity and Specificity

Accuracy of various types of exercise tests often is described by reporting sensitivity and specificity. Sensitivity is the ability of a measurement to identify individuals who are positive, or who have the characteristic that is being measured. If a test produces a high number of false-positive results, then the sensitivity will be low. A false-positive result means that the test result was positive but the characteristic was absent. Young women often have positive stress test results but do not have coronary artery disease. The consequence of a false-positive test result could be unnecessary treatment or further diagnostic testing. Specificity is the ability of a measurement to identify individuals who are negative, or who do not have the characteristic. A high number of false-negative results would produce a low specificity. A false-negative result has a negative test result even though the disease or characteristic is present. The consequence of a false-negative test result is not receiving treatment when it is indicated. Use of the Homans’ sign to screen for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is no longer advocated because the test lacks both sensitivity and specificity.11,12

Objective and Subjective Measurements

Measurements vary in degree of subjectivity versus objectivity. Subjective measurements are those that are affected in some way by the person obtaining the measurement (i.e., the measurer must make a judgment as to the value assigned). The assessment of a patient’s breath sounds is influenced by many factors, including the therapist’s choice of terminology for describing the findings, perception of normal breath sounds, and hearing acuity. The grading of functional skills may be influenced by the therapist’s interpretation of what constitutes minimal versus moderate assistance. Because of the influence of the person performing the measure, subjective measurements usually have lower interrater reliability compared with objective measurements.2

Objective measurements are not affected by the person performing the measure (i.e., these measures do not involve judgment of the measurer). Heart rate measured by a computerized ECG system is an example of an objective measurement. Other examples include measuring blood pressure using an intraarterial catheter and oxygen consumption using a metabolic system. Objective measurements are not necessarily accurate but usually have high interrater reliability.2

Clinical Decision Making

The Hypothesis-Oriented Algorithm for Clinicians II (HOAC-II) intertwines the examination, evaluation, and diagnosis elements into an organized algorithm for clinical decision making.13 Using the HOAC-II, initial data collection (e.g., data from the medical record and patient interview) during the examination allows for generation of patient-identified problems (PIPs) and an initial set of hypotheses that will guide the formulation of an examination strategy (i.e., selection and ordering of tests and measures). These initial measurements help refine the hypotheses and additional measurements are obtained to help confirm or deny the initial set of hypotheses, leading to an eventual hypothesis/physical therapy diagnosis (i.e., an idea of the underlying cause of the patient’s problem), and/or a decision to consult with other health care practitioners. For instance, early in the examination process the therapist may suspect a proximal DVT; the Wells clinical decision rule can aid in deciding whether or not to refer the patient for further testing.14

Selecting Tests and Measures

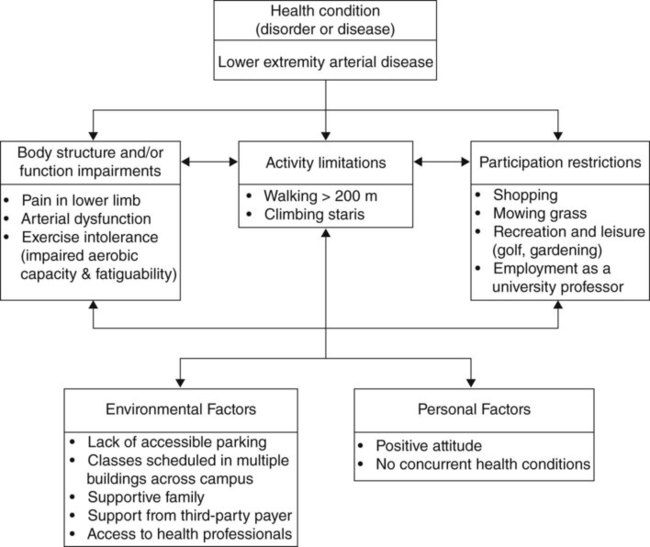

Measurements selected need to be appropriate to the specific health condition (disorder or disease), severity of the condition, and other contextual (i.e., environmental and personal) factors specific to the patient.15 Tests and measures that do not help optimize or assess patient-centered outcomes are an inefficient use of the therapist’s time and add unnecessary costs to health care.

Performing Tests and Measures

General Principles

In clinics where more than one therapist is likely to evaluate or treat a patient, written procedures for performing measurements are necessary. Therapists also need to review the written procedures on a regular basis and practice performing the measures as a group. Practicing together is especially important for therapists who are new to the clinic. Interrater reliability for commonly used measures can be determined. If the reliability is low, written procedures may need to be revised to ensure optimal consistency of measurement. Many commonly used tests and measures, such as blood pressure and 6-minute walk test, have standardized methodology.16,17

Examination

Tests can be categorized as measuring impairments, activity limitations, or participation restrictions as defined by the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model,18 which was recently adopted by the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA).19 A body function or body structure impairment is an abnormality of physiological function or anatomic structure at the tissue, organ, or body system level.15 Examples of impairments include pain, dyspnea, decreased muscle strength or range of motion, abnormal heart rate and blood pressure values, and impaired aerobic capacity. Measurements of impairments are important because they assist therapists in deciphering the causes or reasons for limitations in activity. Activity limitations are difficulties an individual has in performing a task or action.15 Activity limitations can be attributed to physical, social, cognitive, or emotional factors. Examples of activity limitations include the inability to dress, transfer, walk long distances, or climb stairs. Improvements in activity levels usually are of primary interest to patients and families and to those who reimburse for health care. Participation restrictions are those problems that an individual may experience in life situations, such as performing a job requirement or playing a sport.15 Figure 7-1 illustrates a patient’s condition using the ICF model.

Evaluation and Interpretation of Findings

Interpreting measurements is similar to putting the pieces of a puzzle together to create a picture of the patient and his or her activity limitations and participation restrictions. Data are collected from several sources, including the medical record, patient interview, and physical therapy examination. Measures performed and interpreted by other health care professionals can be obtained from the medical record; these include measures such as chest radiographs, blood tests, echocardiography, angiography, and ventilation-perfusion scans. During an interview, patients report information about their current and past medical problems and especially specific patient-identified problems. It is important to be sensitive to patient’s feelings about their condition, noting their stage of emotional recovery. Detecting attitudes related to changing lifestyle habits is also important. After the interview, the therapist should have a sense of the patient as a person and begin to plan an intervention strategy for improving body structure and function impairments, and optimizing activity and participation.13

Minimal Clinically Important Difference

To help facilitate evidence-based practice related to interpreting outcome measurements, a minimal clinically important difference (MCID)—that is, “the minimal level of change required in response to an intervention before the outcome would be considered worthwhile in terms of a patient/client’s function or quality of life”20—has been determined for several endurance/aerobic capacity tests and measures used by physical therapists. Examples include the 6-MWT (54 m21 or 10% improvement22), modified shuttle test (40 m23), and the Borg CR104 and visual analog scale ratings of dyspnea (1 point and 10-20 mm [Table 7-3], respectively24). The MCID for various tests and measures can be used for setting relevant goals, as well as interpreting progress toward outcomes.

Table 7-3

| Grade | Degree of Breathlessness Related to Activities |

| 1 | Not troubled by breathlessness except on strenuous exertion |

| 2 | Short of breath when hurrying on level ground or walking up a slight hill |

| 3 | Walks slower than contemporaries on level ground because of breathlessness, or has to stop for breath after ≈1 mile (or after 15 min) when walking at own pace |

| 4 | Stops for breath after walking about 100 yards (or after a few minutes) on level ground |

| 5 | Too breathless to leave the house, or breathless after dressing or undressing |

Modified by permission from BMJ Publishing Group Limited. From Fletcher CM, Elmes PC, Wood CH: The significance of respiratory symptoms and the diagnosis of chronic bronchitis in a working population, Br Med J 1:257-266, 1959.

Physical Therapy Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Plan of Care

The physical therapy diagnosis serves to drive the selection of interventions. A physical therapy diagnosis may be written in the form of a problem list that may include both impairments and activity limitations. Problems can be listed in order of priority and stated in functional terms. For example, stating “patient unable to climb stairs because of abnormal ECG responses and dizziness,” rather than “abnormal ECG response during activity” is recommended. Alternatively, physical therapy–related classification systems such as the Practice Patterns found in the Guide to Physical Therapist Practice25 may be tailored to reflect the individual’s physical therapy diagnosis.

Based on the results from a 6-MWT, or another appropriate test, a tentative physical therapy diagnosis of impaired aerobic capacity/endurance impairment could be made if the measurement falls outside the reference values for healthy adults.26 Concurrent or complementary measures (e.g., respiratory rate, heart rate and blood pressure response, pulse oximetry, heart and lung sounds, ankle brachial index) could help further refine the hypothesis and determine whether the impaired endurance was more likely due to cardiac, peripheral vascular, or pulmonary impairments.

Intervention

Interventions are physical therapy procedures and techniques designed to produce changes in the patient’s condition. Procedures typically used by therapists treating patients with cardiopulmonary disorders include therapeutic exercise (i.e., aerobic, resistance, breathing exercises), functional training (i.e., work hardening and work conditioning), and airway clearance techniques. The specific intervention selected by the therapist will be influenced by the severity of the cardiopulmonary disorder and the presence of complications. In some cases, the intervention mode and intensity can be derived from the measurement obtained. For instance, 6-MWD can predict peak VO2 in patients with COPD27 and heart failure;28 with this predicted value, converted to METs, the physical therapist can develop an appropriate exercise prescription and guide the patient in selecting physical activities that would fall within a safe and therapeutic range. In addition, a treadmill or overground walking program could be established on the basis of the mean walking velocity during the 6-MWT.29 Likewise, physical activity/exercise intensity could be set based on measurements of perceived exertion or dyspnea obtained during an exercise test.

Reexamination and Outcomes Assessment

As the patient approaches discharge from physical therapy services, the therapist assesses the outcomes of the intervention. The therapist measures the impact of physical therapy services on the patient’s impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions. Examples of outcome measures often used to assess health-related quality of life in patients with cardiopulmonary disorders include the Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire30 and Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire.31

The therapist relates the assessment of outcomes to the original goals established by the therapist and patient. As a result of the outcomes assessment, the therapist may refer the patient back to the physician or to another health care professional. A systematic review of medical records from a group of patients with similar diagnoses can be performed to determine program outcomes of selected physical therapy interventions. See Chapter 17 for a discussion of optimizing outcomes.

Purposes of Documentation

Specific reasons for documentation include the following:

To provide information for other therapists and assistants, who may evaluate and/or treat the patient

To provide information for other therapists and assistants, who may evaluate and/or treat the patient

To communicate with the referring physician and other health care professionals

To communicate with the referring physician and other health care professionals

To provide data to support clinical research, such as treatment effectiveness and efficiency through collection of information on outcomes of various types of care

To provide data to support clinical research, such as treatment effectiveness and efficiency through collection of information on outcomes of various types of care

To verify and support the skilled nature of physical therapy services provided and to justify reimbursement for those services

To verify and support the skilled nature of physical therapy services provided and to justify reimbursement for those services

To address legal and risk management issues by documenting the care provided and the individual’s response to care

To address legal and risk management issues by documenting the care provided and the individual’s response to care

Guidelines for Content and Organization

Writing notes in a clear and concise format is important so that information is conveyed accurately. Examples of unclear notes are those that contain typographical errors, illegible handwriting, or vague statements that can be interpreted in more than one way. Concise notes are more likely to be read by other health care professionals. Most clinicians do not have time in their schedules to read through extensive patient information that may not be relevant. A concise note includes only essential information in a clear communication style free of unnecessary phrases. The APTA’s Defensible Documentation Tips include the following32:

Use only standard or accepted abbreviations. Facilities have lists of approved abbreviations that are available to those who write, read, and review records.

All notations must include the date and time of service.

Documentation of services rendered must match the billing codes submitted to payers.

Tables, headings, and subheadings can be used to help organize the information in an easy-to-find format. Notes must clearly demonstrate the need for skilled, medically necessary services by the physical therapist and the physical therapist assistant.

Patient progression should be evident, with data and assessments provided to support the individual’s achievement of goals or the lack of progression toward set goals.

Communications with the patient, family, health care team, payers, and other related parties involving care should be documented in the chart.

HIPAA Guidelines

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) includes federal guidelines that protect the confidentiality of health information. Personal protected health information (PHI) is to be shared only with persons authorized to view the information (i.e., professionals involved in providing health care). Facilities assume the responsibility of designing systems to ensure that health information is protected and kept confidential. When PHI is stored electronically, controls should be established to ensure only authorized access to information. This may include the use of encryption of laptop computers, memory cards, thumb drives, PDAs, and other portable devices. Therapists must ensure that discussions involving patients’ health information occur in private locations. All health care professionals are bound by these guidelines. Further information may be found at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website (www.hhs.gov/ocr/hipaa/).