Chapter 211 Meaningful Retrospective Analysis

Retrospective Clinical Studies

Retrospective studies represent a major portion of the available evidence in neurologic surgery. Although these types of studies constitute level III or IV evidence (Oxford Center for Evidence-based Medicine Levels of Clinical Evidence [Table 211-1]), they nonetheless represent the majority of neurosurgery evidence to date. There are three major types of nonrandomized clinical studies:

1. Case-control studies (Oxford Center Level III Evidence): Case-control studies are used to identify factors that might lead to a particular outcome by looking retrospectively and comparing cases with a particular outcome to controls without that outcome. When the end point is infrequent, the case-control method is particularly useful because prospective studies would likely require large numbers of patients to have enough power to detect differences between cohorts if the differences did exist. Haines used the case-control approach for studying craniotomy infections.1

2. Nested case-control studies: One variation of the case-control study is the nested case-control study, in which cases of a condition are identified from a defined cohort and, for each case, a selected number of matched controls are selected. This strategy has the advantage of potentially limiting not only the costs that might be associated with doing a large prospective trial but also the confounding biases typically associated with traditional case-control studies, in which the case and control populations differ substantially in ways that might not be apparent to the investigators evaluating the results.2

3. Case series (Oxford Center Level IV Evidence): A study of one group of patients without a comparison group. These studies tend to be descriptive and are best used to provide outcomes data for new techniques or for the treatment of rare disorders.

| Level of Clinical Evidence | Description |

|---|---|

| I | Well-executed randomized controlled trial |

| II | Prospective cohort study with controls |

| III | Case-control study |

| IV | Case series (without control group) |

| V | Expert opinion or theory |

Modified from Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendation, 2001. http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?0=5513.

In some situations, it is advantageous to compare the outcomes from one cohort with those from a cohort treated previously. Fessler et al.’s classic paper comparing corpectomy outcomes to cervical laminectomy outcomes (Nurick grade) is an example.3

Limitations of Randomized Clinical Trial Methodology

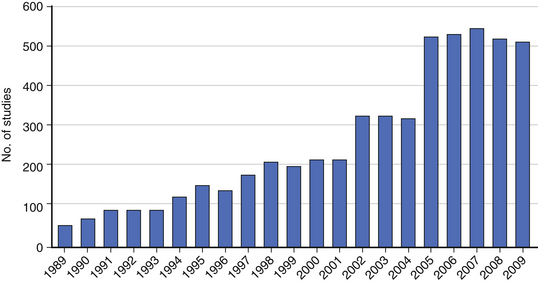

Although the randomized clinical trial (RCT) represents the highest level of clinical evidence, significant barriers exist to performing an RCT in spine surgery. The heterogeneity of spine diseases, the requirement for equipoise, and the learning curve associated with novel procedures are often cited as common challenges in performing RCTs. Even when performed, the results of RCTs are difficult to interpret or do not provide a clear answer to the research question (see Chapter 210). For these and many other reasons, nonrandomized clinical studies including retrospective studies remain an important research tool for spine surgeons. In fact, the number of published retrospective clinical studies continues to increase (Fig. 211-1). Prospective registries may represent an alternative to the RCT, although they pose the risk of generating data that can be difficult to interpret without clearly defined entry and exclusion criteria and control groups.

Advantages of Retrospective Methodology

Retrospective studies may, in some situations, evaluate more diverse patient populations and, as a result, provide data that more closely informs actual clinical practice. A study by Glassman et al. evaluated the effect of sagittal imbalance on health status by retrospectively reviewing 752 patients with various degrees of adult deformity. The study demonstrated that increasing sagittal imbalance correlates with worsening health status.4 In a companion study, Glassman et al. further identified sagittal imbalance as a reliable predictor of clinical symptoms relative to a number of other patient characteristics.5 Although the associations identified in these retrospective studies could not establish cause and effect, they are very useful for practicing spine surgeons interested in treating spine deformity.

Retrospective studies and prospective clinical trials can be viewed as working cooperatively to provide comprehensive evidence. Retrospective studies represent the observational first step that is critical for uncovering patterns among a vast array of patient factors and outcomes.6 From these patterns, hypotheses can be generated to identify potential causal relationships. RCTs alternatively represent the scientific experimentation step that either confirms or refutes these causal relationships. RCTs are well suited to test the effectiveness of an intervention by controlling for differences in baseline patient characteristics; however, retrospective studies are often very useful for identifying which patient characteristics are the most relevant in predicting outcomes. Both observation and experimentation steps are essential for scientific advancement.

The primary utility of the retrospective study is in identifying patterns among patient characteristics (e.g., risk factors, prognostic indicators) and their potential effect on clinical outcomes. This advantage is particularly evident in studying infrequent or delayed outcomes. For example, Cammisa et al. retrospectively reviewed 2144 patients treated over a 9-year period to identify factors associated with an incidental durotomy. They identified a 3.1% rate of durotomy in spine surgery patients.7 They found that incidental durotomies occurred more frequently in patients with prior surgery, and, that overall, with appropriate repair, patients with durotomies did not suffer any long-term sequelae compared with patients without durotomy. An RCT to address this particular question would have required 10 years to perform and likely would have cost millions of dollars.

Adjacent-level disease is another example of a relatively low-frequency event following spine surgery that has been studied using retrospective studies. The concept (although it is controversial) has fueled the development of motion-preservation techniques in spine surgery. In a landmark paper, Hilibrand et al. retrospectively evaluated 374 patients for delayed incidence of adjacent-segment degeneration following anterior cervical fusion up to 10 years postoperatively.8 They determined that the annual incidence of symptomatic adjacent-segment disease was 2.9% in these patients. The retrospective approach allowed for the quantification of the frequency of adjacent-level disease, but it could not establish its cause. Although further prospective studies are still needed to truly understand whether fusion causes adjacent-level disease, retrospective studies help to frame questions for further study and identify rates of various complications or other clinical events.

Retrospective studies can evaluate questions that might be impossible or unethical with an RCT. To study the effect of quitting smoking on spine fusion, Glassman et al. retrospectively reviewed 357 patients who underwent lumbar instrumented fusion. They found the nonunion rate was 14.2% for nonsmokers. They used follow-up telephone surveys to determine whether smokers quit smoking after surgery for at least 6 months and used this approach to assess the potential value of smoking cessation after lumbar spine fusion surgery. Cessation of smoking for at least 6 months after surgery was associated with a nonunion rate of 17.1%, whereas the nonunion rate was 26.5% in patients who continued to smoke after surgery.9

Retrospective methodologies avoid a specific type of bias, known as the Hawthorne effect, in which the patient’s and/or the physician’s behaviors are altered as a direct result of being observed, thereby influencing the treatment effect.10 This phenomenon is relevant in spine surgery RCTs, particularly medical device studies, because both patients and physicians may demonstrate heightened enthusiasm for potentially more attractive newer technology. Resnick et al. identified an example of this phenomenon in the RCT comparing the Prestige (Medtronic, Memphis, TN) cervical disc arthroplasty to single-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF).11 The investigators found that patients randomized to the novel device technology (Prestige arthroplasty) had better neurologic outcomes than those undergoing conventional ACDF.12 Resnick et al. noted that the surgical neural decompression for both the Prestige and ACDF procedures was identical, and, as such, better neurologic outcomes with the disc replacement were seemingly implausible. True differences in neurologic outcome, however, may have been attributable to better attention being paid to detail during the arthroplasty procedure as participating surgeons established experience and facility with the device, or perhaps a more optimistic view was expressed by patients who were pleased to have received the novel technology. Retrospective studies inherently eliminate this bias as they, de facto, initiate investigation after whatever treatment effect and outcome have already occurred.

Limitations of Retrospective Methodology

The primary criticism of retrospective studies is that unrecognized confounding factors may ultimately distort results.13 Conventional wisdom suggests that confounding variables are pervasive and unpredictable, and therefore retrospective studies fraught with confounders may be biased and lead to conclusions that might later prove to be untrue. The RCT controls balances confounders (known and unknown) and therefore reduces that chance of confounder bias. Nevertheless, recent studies demonstrate the value of retrospective studies when inherent limitations are addressed. In a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine, Benson and Hartz reviewed 136 articles in 19 treatment areas to compare the findings of observational studies and RCTs.13 They found the estimates of treatment effect in observational studies were comparable to RCTs in nearly all areas. In an analogous study, Concato et al. reviewed 99 reports on five clinical topics and found that the average results from the case-control and cohort studies were remarkably similar to those obtained from RCTs and, in fact, demonstrated less variability in point estimates (i.e., less heterogeneity of results).14 These studies contend that retrospective and nonrandomized studies can produce high-quality evidence that compares favorably with that from RCTs. Both of these studies, however, state that the usefulness of retrospective study evidence depends on study design with sophisticated data sets, better statistical methods, and proper identification of any inherent limitations or biases.

Confounders in clinical investigation are systematic errors that cause a tendency toward erroneous results.15 The two most common confounders in retrospective studies that distort results are selection bias and missing data. Selection bias occurs when an independent baseline characteristic (that directly affects the assessed outcome measure) differs between the study and the control population. In retrospective studies, allocation of patients into study and control groups is determined by the treating the physician’s discretion and the patient’s preference, whereas randomization (with sufficient numbers) theoretically equalizes baseline differences between groups. It is common, for example, in retrospective neurosurgical studies, to find healthier patients in a surgical cohort that are then compared with patients with greater medical comorbidities treated with a medical or less aggressive strategy. Missing data can confound retrospective studies in a number of ways. Attrition is one mechanism in which missing data are not random. Patients who are lost to follow-up may represent those who are clinically improved and therefore no longer seek further medical attention or, in contrast, may represent those who are displeased with their care and are seeking care elsewhere. Studies, for example, that retrospectively determined the rate of adjacent-level disease in the cervical spine following fusion might have overestimated this rate. It is likely that patients who are clinically doing well after cervical fusion would be less likely to follow-up and have radiographs taken, thus inflating the rate of abnormal radiographs. Attrition is particularly problematic in retrospective studies as opportunities to contact patients to complete follow-up may be limited and are often not possible.

Administrative Databases

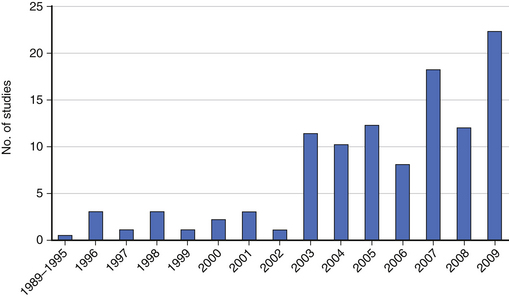

Large administrative databases containing vast amounts of patient data have increased our opportunities to generate meaningful evidence using retrospective data (Fig. 211-2). However, these databases sometimes introduce new problems in study design, such as the lack of specificity of coding systems that were designed decades ago for coding new treatments and disease entities, undercoding of some important prognostic factors, and difficulty disentangling some presenting signs and symptoms of disease from treatment complications.16 In addition, administrative databases lack validated patient-reported outcomes data and often have large amounts of missing data. Nevertheless, administrative databases contain valuable clinical data that are publically available. Two of the major types of administrative databases used for clinical research are:

1. State Inpatient Databases: The state inpatient databases (SIDs) are part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The SID contains demographic data, admission date and discharge date, procedure and diagnosis codes using the International Classification of Diseases-ninth revision Clinical Modification (ICD-9 CM), diagnostic related group (DRG), hospital code, charge data, length of stay, disposition, and inpatient deaths. Five of the SIDs contain consistent patient identifiers across several years, permitting longitudinal follow-up of individual patients. For example, Martin et al. have used the Washington State SID to study lumbar spine reoperation rates over time.17

2. Nationwide Inpatient Sample: The nationwide inpatient sample (NIS) is part of the HCUP sponsored by the Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality and represents a weighted sample from the SIDs that is readily generalized to the entire U.S. nonfederal hospital universe. It includes data from about 1000 hospitals and represents a 20% stratified probability sample of American inpatient discharges. Although this database is much larger than the SIDs, it does not contain patient identifiers, and therefore analysis of individual patient data is possible for one admission only. The database has been used to study inpatient complication rates and mortality in a variety of neurosurgical conditions, including cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM), using algorithms based on specific ICD-9-CM codes.16 In addition, several investigators have used the NIS to demonstrate the effect of hospital and surgeon volume on the morbidity and mortality of treating many neurosurgical conditions, including intracranial aneurysms, craniotomies for meningioma, and pediatric CSF shunts.18–21

Complication Outcomes

The NIS has been useful for understanding more about the complication rates from surgery for CSM. In a large retrospective cohort review of U.S. hospital admissions for cervical spine surgery using the NIS from 1992 through 2001, Wang et al. found that surgery for cervical spondylosis with myelopathy (19% of 932,009 admissions) was associated with higher complication rates than other types of cervical spine surgery.16 Similarly, another recent study found the complication rate after CSM surgery in patients older than 75 was 38% compared with 6% in younger patients.22 Another study also used the NIS (1993–2002; 58,115 admissions) to compare complication rates between ventral and dorsal fusion procedures for CSM. This retrospective analysis identified a complication rate of 11.9% for ventral surgery versus 16.4% for dorsal fusion surgery.23

Cost Outcomes

Administrative databases often contain data including hospital charges to estimate hospital costs. Real hospital costs can be estimated using coding systems such as the Health Care Financing Administration Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS). In addition, Medicare reimbursement rates for specific hospital billing codes (ICD-9 and DRG) are readily available and are used to estimate costs of health care as well.24 Recently, King et al. used the Washington State Inpatient Database (1998–2002) to compare hospital charges for ventral fusion surgery versus dorsal surgery to treat cervical degenerative disease. In this retrospective study, median hospital charges for dorsal decompression were 62% higher than charges for ventral surgery ($23,300 vs. $14,400).25

Summary

Retrospective studies with clear inclusion and exclusion criteria to define study and control populations with efforts to balance known prognostic factors can compare favorably with the level of evidence provided by RCTs.14,26 RCTs have the advantage of being the optimal method for balancing both known and unknown prognostic factors that are associated with the observed outcomes in a trial. When conducting a retrospective trial, it is important to identify and minimize bias and make conclusions accordingly. Finally, the large numbers contained within administrative databases give an enormous power to the spine surgeon who aims to understand rare clinical events using retrospective methodology.

Benson K., Hartz A.J. A comparison of observational studies and randomized, controlled trials. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(25):1878-1886.

Concato J., Shah N., Horwitz R.I. Randomized, controlled trials, observational studies, and the hierarchy of research designs. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(25):1887-1892.

Hartz A., Marsh J.L. Methodologic issues in observational studies. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;413:33-42.

Martin B.I., Mirza S.K., Comstock B.A., et al. Are lumbar spine reoperation rates falling with greater use of fusion surgery and new surgical technology? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(19):2119-2126.

McKee M., Britton A., Black N., et al. Methods in health services research. Interpreting the evidence: choosing between randomised and non-randomised studies. BMJ. 1999;319(7205):312-315.

1. Haines S.J. Topical antibiotic prophylaxis in neurosurgery. Neurosurgery. 1982;11(2):250-253.

2. Ernster V.L. Nested case-control studies. Prev Med. 1994;23(5):587-590.

3. Fessler R.G., Steck J.C., Giovanini M.A. Anterior cervical corpectomy for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Neurosurgery. 1998;43(2):257-265. discussion 265–267

4. Glassman S.D., Bridwell K., Dimar J.R., et al. The impact of positive sagittal balance in adult spinal deformity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(18):2024-2029.

5. Glassman S.D., Berven S., Bridwell K., et al. Correlation of radiographic parameters and clinical symptoms in adult scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(6):682-688.

6. Manchikanti L., Singh V., Smith H.S., Hirsch J.A. Evidence-based medicine, systematic reviews, and guidelines in interventional pain management: part 4: observational studies. Pain Physician. 2009;12(1):73-108.

7. Cammisa F.P.Jr., Girardi F.P., Sangani P.K., et al. Incidental durotomy in spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(20):2663-2667.

8. Hilibrand A.S., Carlson G.D., Palumbo M.A., et al. Radiculopathy and myelopathy at segments adjacent to the site of a previous anterior cervical arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1999;81(4):519-528.

9. Glassman S.D., Anagnost S.C., Parker A., et al. The effect of cigarette smoking and smoking cessation on spinal fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(20):2608-2615.

10. Kao L.S., Tyson J.E., Blakely M.L., Lally K.P. Clinical research methodology I: introduction to randomized trials. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206(2):361-369.

11. Resnick D.K., Rajpal S., Steinmetz M.P. Common pitfalls in interpretation of medical evidence: a case demonstration of misleading interpretation in the analysis of cervical spine fusions. Spine J. 2009;9(11):905-909.

12. Mummaneni P.V., Burkus J.K., Haid R.W., et al. Clinical and radiographic analysis of cervical disc arthroplasty compared with allograft fusion: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Neurosurg. 2007;6(3):198-209.

13. Benson K., Hartz A.J. A comparison of observational studies and randomized, controlled trials. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(25):1878-1886.

14. Concato J., Shah N., Horwitz R.I. Randomized, controlled trials, observational studies, and the hierarchy of research designs. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(25):1887-1892.

15. Hartz A., Marsh J.L. Methodologic issues in observational studies. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;413:33-42.

16. Wang M.C., Chan L., Maiman D.J., et al. Complications and mortality associated with cervical spine surgery for degenerative disease in the United States. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(3):342-347.

17. Martin B.I., Mirza S.K., Comstock B.A., et al. Are lumbar spine reoperation rates falling with greater use of fusion surgery and new surgical technology? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(19):2119-2126.

18. Barker F.G.2nd, Amin-Hanjani S., Butler W.E., et al. In-hospital mortality and morbidity after surgical treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms in the United States, 1996–2000: the effect of hospital and surgeon volume. Neurosurgery. 2003;52(5):995-1007. discussion 1009

19. Barker F.G.2nd, Klibanski A., Swearingen B. Transsphenoidal surgery for pituitary tumors in the United States, 1996–2000: mortality, morbidity, and the effects of hospital and surgeon volume. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(10):4709-4719.

20. Curry W.T., McDermott M.W., Carter B.S., et al. Craniotomy for meningioma in the United States between 1988 and 2000: decreasing rate of mortality and the effect of provider caseload. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(6):977-986.

21. Hoh B.L., Rabinov J.D., Pryor J.C., et al. In-hospital morbidity and mortality after endovascular treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms in the United States, 1996–2000: effect of hospital and physician volume. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24(7):1409-1420.

22. Holly L.T., Moftakhar P., Khoo L.T., et al. Surgical outcomes of elderly patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Surg Neurol. 2008;69(3):233-240.

23. Boakye M., Patil C.G., Santarelli J., et al. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: complications and outcomes after spinal fusion. Neurosurgery. 2008;62(2):455-461. discussion 461–462

24. Rutigliano M.J. Cost effectiveness analysis: a review. Neurosurgery. 1995;37(3):436-443. discussion 443–444

25. King J.T.Jr., Abbed K.M., Gould G.C., et al. Cervical spine reoperation rates and hospital resource utilization after initial surgery for degenerative cervical spine disease in 12,338 patients in Washington State. Neurosurgery. 65(6), 2009. 1011–1122discussion 1122–1123

26. McKee M., Britton A., Black N., et al. Methods in health services research. Interpreting the evidence: choosing between randomised and non-randomised studies. BMJ. 1999;319(7205):312-315.