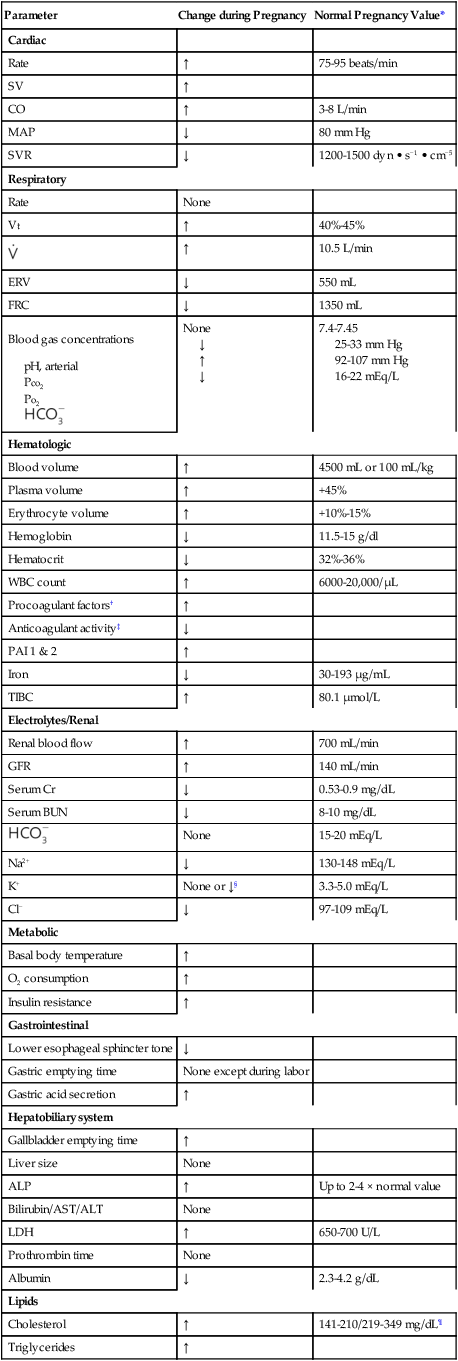

Maternal physiologic changes in pregnancy

Maternal physiologic changes in pregnancy begin approximately 5 weeks after implantation and may not return to normal until 8 weeks after delivery (Table 180-1).

Table 180-1

Maternal Physiologic Changes during Pregnancy

| Parameter | Change during Pregnancy | Normal Pregnancy Value* |

| Cardiac | ||

| Rate | ↑ | 75-95 beats/min |

| SV | ↑ | |

| CO | ↑ | 3-8 L/min |

| MAP | ↓ | 80 mm Hg |

| SVR | ↓ | 1200-1500 dyn • s−1 • cm−5 |

| Respiratory | ||

| Rate | None | |

| VT | ↑ | 40%-45% |

| ↑ | 10.5 L/min | |

| ERV | ↓ | 550 mL |

| FRC | ↓ | 1350 mL |

|

Blood gas concentrations |

None ↓ ↑ ↓ |

7.4-7.45 25-33 mm Hg 92-107 mm Hg 16-22 mEq/L |

| Hematologic | ||

| Blood volume | ↑ | 4500 mL or 100 mL/kg |

| Plasma volume | ↑ | +45% |

| Erythrocyte volume | ↑ | +10%-15% |

| Hemoglobin | ↓ | 11.5-15 g/dl |

| Hematocrit | ↓ | 32%-36% |

| WBC count | ↑ | 6000-20,000/μL |

| Procoagulant factors† | ↑ | |

| Anticoagulant activity‡ | ↓ | |

| PAI 1 & 2 | ↑ | |

| Iron | ↓ | 30-193 μg/mL |

| TIBC | ↑ | 80.1 μmol/L |

| Electrolytes/Renal | ||

| Renal blood flow | ↑ | 700 mL/min |

| GFR | ↑ | 140 mL/min |

| Serum Cr | ↓ | 0.53-0.9 mg/dL |

| Serum BUN | ↓ | 8-10 mg/dL |

| None | 15-20 mEq/L | |

| Na2+ | ↓ | 130-148 mEq/L |

| K+ | None or ↓§ | 3.3-5.0 mEq/L |

| Cl− | ↓ | 97-109 mEq/L |

| Metabolic | ||

| Basal body temperature | ↑ | |

| O2 consumption | ↑ | |

| Insulin resistance | ↑ | |

| Gastrointestinal | ||

| Lower esophageal sphincter tone | ↓ | |

| Gastric emptying time | None except during labor | |

| Gastric acid secretion | ↑ | |

| Hepatobiliary system | ||

| Gallbladder emptying time | ↑ | |

| Liver size | None | |

| ALP | ↑ | Up to 2-4 × normal value |

| Bilirubin/AST/ALT | None | |

| LDH | ↑ | 650-700 U/L |

| Prothrombin time | None | |

| Albumin | ↓ | 2.3-4.2 g/dL |

| Lipids | ||

| Cholesterol | ↑ | 141-210/219-349 mg/dL¶ |

| Triglycerides | ↑ |

*Values are approximate and vary throughout pregnancy.

†Factors XII:c, VII:c, VII, and V; von Willebrand factors; and fibrinogen.

‡Activated protein C and protein S.

§Although there are total body accumulations of Na+ and K+, because of the retention of fluid and increase in plasma volumes, concentrations decrease.

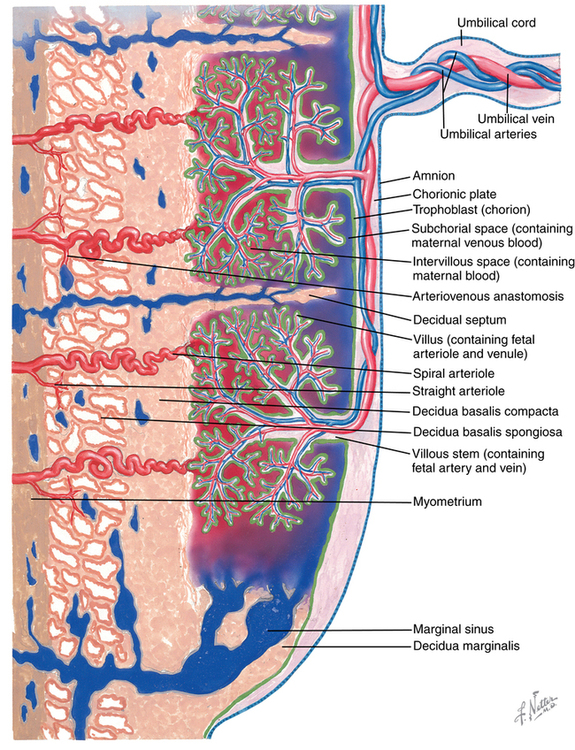

Uterine physiology

Uterine blood flow and placental perfusion are affected by systemic vascular resistance, aortocaval compression, and uterine contraction. Placental blood supply is determined by spiral intervillous arteries, which are maximally dilated (Figure 180-1). They are supplied by arcuate and radial arteries, the ovarian arteries, and uterine arteries. Myometrial tension decreases the caliber of spiral arteries, reducing placental perfusion. Spiral arteries are maximally dilated and sensitive to the effects of α-adrenergic receptor agonists (e.g., phenylephrine). Vasoconstriction can cause dramatic changes in placental blood supply. The surface area and integrity of the placenta are affected by maternal and placental disorders.