CHAPTER 47 Management of trichiasis/distichiasis

Definition of trichiasis

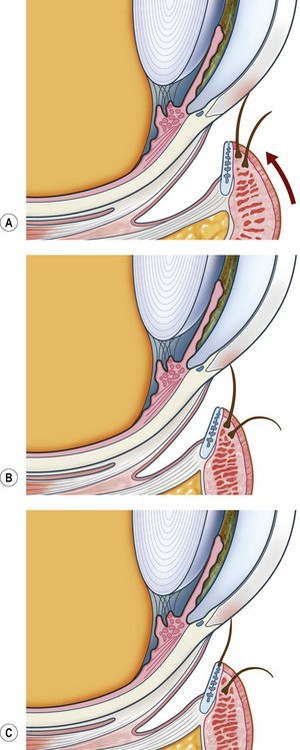

Trichiasis is defined as an eyelash that touches the eye but arises from the anterior aspect of the lid margin. It is distinguished from ‘aberrant’ lashes that arise from the meibomian gland openings near the posterior lid margin and ‘misdirected’ lashes that arise from the lid margin and are abnormally directed. Distichiasis is a condition where lashes arise from the orifices of the meibomian glands. However, common parlance often uses the word ‘trichiasis’ to mean any or all of the above. The terms ‘lash-induced trichiasis’ and ‘lid-induced trichiasis’ are also in usage (Fig. 47.1).

Physiology of normal eyelash formation

Hair is formed by the replication of cells within the hair follicles1. Follicles may produce either ‘lanugo’ (fetal hair), ‘vellus’ or ‘terminal’ hairs. Eyelashes, eyebrows, scalp hair and pubic hair are all terminal hairs while vellus hair cover the rest of the body and is associated with ‘goose-pimples’ due to erector pili units. Eyelash follicles are located anterior to the tarsal plate, deep to orbicularis oculi and adjacent to the inferior or superior marginal arterial arcades. The upper lid follicles are deeper (1.8 vs. 1.0 mm) and the bulbs are wider (188 vs. 132 microns). The upper lid has twice the number of follicles2.

Hair growth occurs in a cyclical manner with the follicles undergoing growth, atrophy, and then inactivity; anagen, catagen, and telogen1. The duration of each phase of the cycle depends on the type of hair and its location. Eyelashes have an optimum length and this is regulated by the hair cycle. They grow for 10 weeks followed by a resting period of 9 months3. During the resting phase the lashes may be lost. This mechanism regulates the length of the lashes by stopping growth after they have reached the ‘correct length’. In comparison, scalp hairs grow for 2–6 years and then rest for 3 months. Therefore, scalp hair grows longer.

Pathophysiology of abnormal eyelash formation

Aberrant lashes are usually ‘stunted and non-pigmented’ and arise from the meibomian glands. They may be congenital as in distichiasis. Acquired aberrant lashes occur after prolonged lid inflammation such as occurs in Stevens–Johnston syndrome or ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (OCP). Scheie and Albert4 state that acquired aberrant lashes are due to ‘meibomian glands [which] become modified and take on an atavistic hair-bearing function.’ Most human body hairs are associated with sebaceous glands and eyelashes are atypical in that they are not. In contrast, histology of congenital distichiasis shows that the meibomian glands are absent or rudimentary and this is presumably different from the acquired form. These congenital distichiasis follicles can be at very distant locations within the tarsal plate and this is important to any subsequent focal treatments for ablation5.

Pathophysiology of eyelash ablation

The hair cycle is important to effecting permanent lash ablation. If hair growth is asynchronous, then the ratio of growth to inactivity reflects the number of follicles in different stages. At any given time, up to 75% of eyelash follicles are inactive compared with 13% of human scalp follicles6. This affects the outcome of epilation. Plucking during an inactive phase actively induces new growth.

Cryotherapy for trichiasis

Cryotherapy can treat large numbers of lashes simultaneously. The pathologic reaction to cryotherapy depends on the temperature. In rabbits, at –15°C there is complete retention of the lash follicles but significant, permanent depigmentation of the melanocytes. At –30°C the follicles and the meibomian glands are replaced by a dermal scar7. Effective cryotherapy for trichiasis will always be accompanied by a hypopigmented epidermis because the melanocytes are more sensitive to cryotherapy than lash follicles8. This is very important in dark-skinned people. However, cosmetically this may be reduced by splitting the eyelid and selectively treating the lash follicles or by only treating the lid margin and posterior lid surface. In humans, clinical studies suggest that –20°C is satisfactory9.

Cryotherapy achieves a long-term success rate of 70–90% in non-cicatricial lid disease; however, complications occur in up to 26%10. These include severe short-term lid edema, lid depigmentation, destruction of meibomian glands, lid notching, and induction of further trichiasis (in 9%). Marked progression of symblepharon and conjunctival scarring was noted in 77% of patients with OCP in the absence of immunosuppression10. The least complications occur in eyes without conjunctival inflammation11. In trichiasis due to trachoma cryotherapy was successful in 27–56%. This is based on two studies that had assessed success with a Kaplan–Meier analysis over long periods of time12.

The relative lack of success of cryotherapy may be due to the lack of adequate freezing. Clinically, various authors have often relied on a specific duration of freezing based on previous correlations with a thermocouple. However, this depends markedly on the type of probe used. For example, for an eyelid to reach –20°C requires 45 seconds with the Cryomedics MT650 probe, 30 seconds with the Amoilette cryoprobe, and 25 seconds with the Collin cryoprobe9,10. The other clinical method is to apply the cryotherapy until there has been adequate ‘whitening’ of the affected area. The laboratory evidence suggests that there is 100% destruction of lash follicles if they are frozen to −30°C in two cycles7. If this is correct, then the clinical failure is solely due to inadequate freezing of the follicles.

Electrolysis for trichiasis

Histology reveals focal necrosis and destruction of the follicle with minimal surrounding soft tissue reaction. In rabbits, an occasional specimen shows peri-follicular scarring13. Factors important in electrical burns include the amperage, voltage, alternating current, the resistance of the tissues, and the duration of the application.

Despite its widespread use, the specific methodology and long-term assessment of efficacy are limited in the literature. Fox14 suggests a current of 2.5 mA, while others all reiterate 2.0–3.5 mA for 5–10 seconds12. It has also been suggested that the current be adjusted empirically and that the electrode should be inserted 2 mm into the follicle and that the hair should lift out easily after the application. If it does not, then the treatment should be repeated immediately. Reacher et al.’s study12 assessed upper lid trichiasis due to trachoma. They used 2.0–3.5 mA for 10 seconds, but did not epilate afterwards. A Kaplan–Meier survival analysis showed a 70% cumulative chance of success at 5 months but this fell to 35% at 10 months and 29% at 20 months. Given the length of the hair cycle, at least 1 year of follow-up is required to adequately assess success of an ablative procedure.

Argon laser thermoablation

Argon laser thermoablation involves repeatedly applying argon laser burns to the hair root site. The follicle subsequently becomes exposed and is ‘burnt’ down to its base with successive applications. Each lash is treated separately. An initial spot size of 50 µm is used to form a shallow crater at the exit site of the lash and then a 100 µm spot size is used to deepen the crater to approximately 2 mm. A 200 µm spot size is then used to ‘thoroughly treat’ the base of the crater15,16. Anesthesia ranges from nothing to topical drops to infiltrative anesthesia.

Histologically, argon laser thermoablation of rabbit lashes causes permanent follicular destruction13. There is immediate necrosis of the follicles and the superficial epidermis. This is followed by a localized acute inflammatory reaction. Within 2 weeks, the follicles have been replaced by a dermal scar but the adjacent pilosebaceous units remain normal.

Surgery

A significant cluster of posterior lid margin lashes is a contraindication to surgery and should be ablated. However, single lashes can have the follicle surgically removed5. An operating microscope is highly desirable for this.

1 Spearman RIC. The structure and function of the fully developed follicle, vol. 4. Jarrett A, editor. The Physiology and Pathophysiology of the Skin. London: Academic Press; 1977:1283-1287.

2 Elder MJ. Anatomy and physiology of eyelash follicles and its relevance to lash ablation procedures. J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;13:21-25.

3 Munro DD. Disorders affecting the skin appendages. In: Fitzpatrick TB, editor. Dermatology in General Medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill Inc, 1971. Chapter 9

4 Scheie HG, Albert DM. Distichiasis and trichiasis: Origin and management. Am J Ophthalmol. 1966;61:718-720.

5 Wolfley D. Excision of individual follicles for the management of congenital distichiasis and localized trichiasis. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1987;24:22-26.

6 Orentreich N. Scalp hair replacement in man, vol. 9. Montagna W, Ellis RA, editors. The Biology of Hair Growth. New York and London: Academic Press, 1958. Chapter 6

7 Sullivan JH, Beard C, Bullock TD. Cryosurgery for treatment of trichiasis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1976;82:117-121.

8 Soll DB, Harrison SE. Basic concepts and an overview of cryosurgery in ophthalmic plastic surgery. Ophthalmic Surg. 1979;10:31-36.

9 Johnson RJ, Collin JRO. Treatment of trichiasis with a lid cryoprobe. Br J Ophthalmol. 1985;69:267-270.

10 Wood JR, Anderson RL. Complications of cryosurgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981;99:460-463.

11 Foster CS. Cicatricial pemphigoid. Tr Am Ophth Soc. 1986;84:527-663.

12 Reacher MH, Munoz B, Alghassany A, et al. A controlled trial of surgery for trachomatous trichiasis of the upper lid. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992;110:667-674.

13 Bartley GB, Bullock JD, Olsen TG, et al. An experimental study to compare methods of eyelash ablation. Ophthalmology. 1987;94:1286-1289.

14 Fox SA. Ophthalmic Plastic Surgery, 4th edn. New York: Grune and Stratton; 1970. p. 333

15 Awan KJ. Laser photocoagulation – vaporization therapy of trichiasis. Ophthalmic Laser Therapy. 1988;3:3-9.

16 Sharif KW, Arafat AFA, Wykes WC. The treatment of recurrent trichiasis with the argon laser photocoagulation. Eye. 1991;5:591-595.