Management of the difficult airway

Preoperative evaluation

Tongue versus pharyngeal size

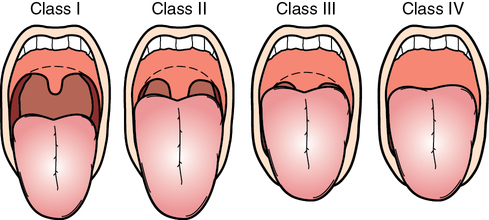

Preinduction visualization of the faucial pillars, soft palate, and base of the uvula, with the patient in a sitting position, is used to classify patients according to how well pharyngeal structures can be seen (Table 240-1 and Figure 240-1). Mallampati and colleagues’ original recommendation was to examine these structures without the patient phonating and to assign a class level—I through III (see Table 240-1)—to the results. Class II was later subdivided based on whether all of the uvula or only its base can be visualized.

Table 240-1

Mallampati Classification of the Upper Airway

| Class | Visible Structures |

| I | Palate, faucial pillars, entire uvula |

| II | Palate, faucial pillars, base of uvula |

| III | Palate, some of the faucial pillars |

| IV | Palate |

Defining the difficult airway

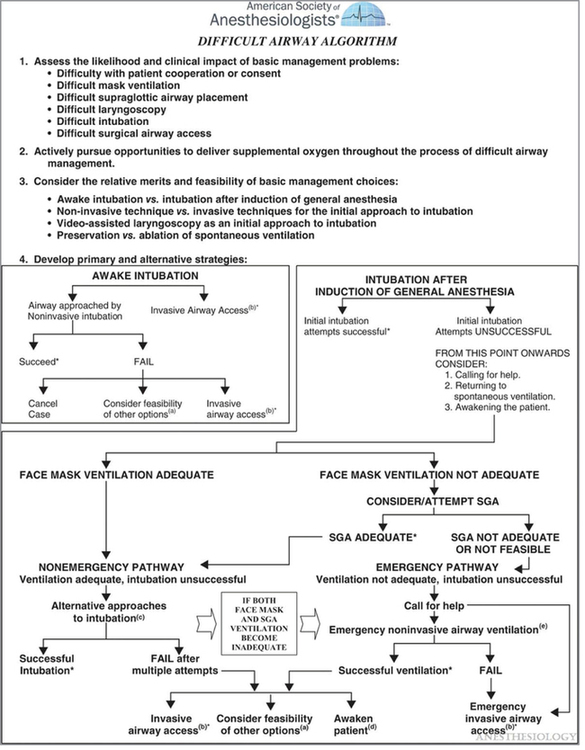

By definition, a difficult airway is a clinical situation in which an anesthesia provider experiences difficulty with facemask ventilation of the upper airway, with direct laryngoscopy, or with tracheal intubation. In the 1990s, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) developed the first practice guidelines and an algorithm for managing the difficult airway and began emphasizing that anesthesia providers needed to learn multiple airway management techniques. This instruction led to anesthesia providers’ increased familiarity with multiple airway instruments and a willingness to switch techniques sooner, rather than later, when encountering a difficult airway. The 2013 update of the ASA Difficult Airway Algorithm (Figure 240-2) mentions the use of video laryngoscopy as another useful approach. This mirrors the widespread adoption of video laryngoscopy techniques by most anesthesia providers as their favored approach to anticipated difficult airways.

Management of the difficult airway

The anesthesia provider may have more difficulty mask ventilating a morbidly obese patient (i.e., body mass index > 40 kg/m2), but morbid obesity does not, per se, lead to difficulty in intubating the airway unless the patient has increased periglottic tissue or limited neck mobility or if problems are encountered in positioning the patient. Additionally, obese patients develop rapid O2 desaturation during apnea. These factors can be ameliorated by placing the patient in a “ramped up” position (see Chapter 163).

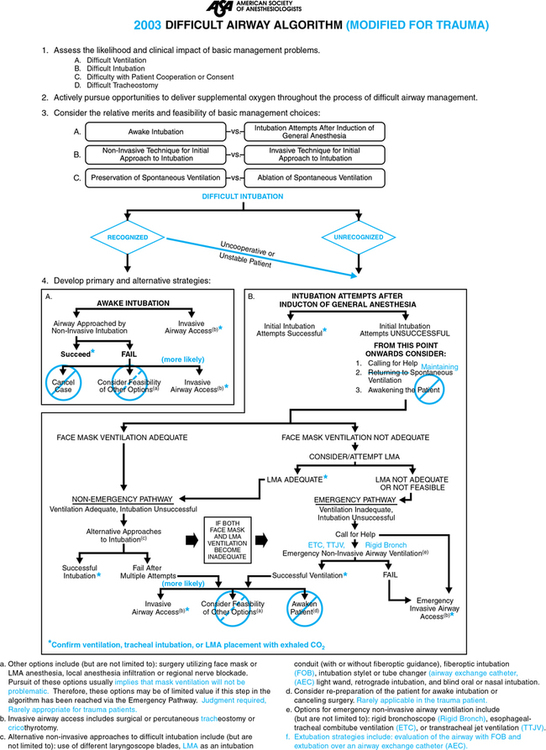

Only rarely is a surgical airway the first choice for securing an airway. The most common reasons include trauma to the face or cervical spine or a neoplastic disease involving the airway or neck. Because of the differences in managing the airway of patients with trauma, the ASA modified the Difficult Airway Algorithm for use in trauma patients (Figure 240-3).