Chapter 190 Management of Primary Malignant Tumors of the Osseous Spine

Primary tumors of the spine are exceedingly rare. Owing to their rarity, few surgeons had gained enough experience and insight into their management until the 1970s when B. Stener first applied oncologic criteria in resecting spine tumors, previously submitted only to intralesional excisions (curettage). Stener1 was the first to plan and perform en bloc resections as they were already being performed in tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. His works are still unsurpassed examples of adapting surgery to tumor expansion and anatomic constraints to achieve a tumor-free margin by en bloc resection.

Later, R. Roy-Camille2 popularized a technique to standardize en bloc resection in the thoracic spine by the posterior approach and in the lumbar spine by a combined posterior and anterior approach. Some years later, K. Tomita3 proposed a similar technique, characterized by the use of a saw thinner than the Gigli saw, proposing to remove en bloc also the posterior arch. However, what is missing in these capital contributions—which represent the foundations upon which other surgeons have further advanced—is any consideration of the margins to be achieved, thus reducing the oncologic interest. These concepts were first applied to bone tumor by Enneking4 and more specifically to bone tumors of the spine by Campanacci and colleagues5 and by Talac and colleagues.6

Many examples are reported in the most recent literature of highly technically demanding surgical procedures performed either in tumors of the cervical or cervicothoracic spine,7–11 including in the resection functionally relevant structures with the purpose of achieving tumor-free margins.12–13

Classification

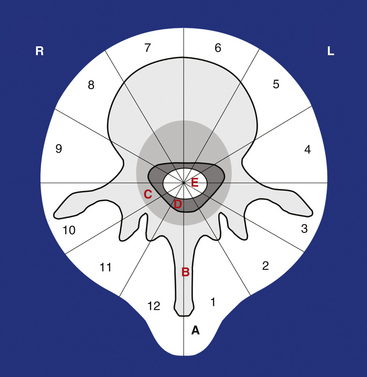

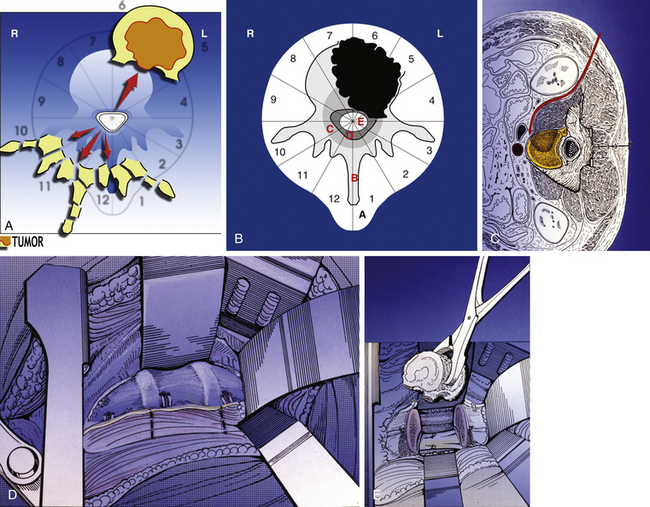

Less than 5% of the 2500 primary malignant bone tumors that are found each year in the United States occur in the spine.14 For that reason, few centers can achieve a critical level of experience in the management of these tumors. The terminology used to describe these tumors has tended to vary considerably from one region to the next. In addition, there were no staging systems that helped one decide which type of surgery to perform. All of these reasons entered into our decision to help develop the Weinstein, Boriani, Biagini (WBB) surgical staging system.15 This system is designed to unify the ways tumors are described in order to facilitate communication between physicians. Once a common descriptive language is accepted, it also helps to facilitate research efforts. The WBB system helps guide the surgeon with regard to what type of resection is possible.

The WBB system divides the axial presentation of the vertebrae involved with tumor into 12 zones similar to a clock face (Fig. 190-1). Position number 1 begins at the left half of the spinous process and position 12 ends at the right half of the spinous process. Zones 4 and 9 are particularly important to know because they define respectively the left and the right pedicle. Vertebrectomy with adequate surgical margins depends upon one of these two zones to be free of tumor. The vertebra is further divided into radial zones. The radial zones define the depth of tumor invasion. For instance, zone A represents a soft tissue mass extending beyond the confines of the bony cortex. Zone B describes tumor within the superifical bony vertebrae, and zone C defines tumor within the deep bony vertebrae. Zone D describes epidural tumor involvement and zone E is intradural. It is also important to describe the longitudinal extend of the tumor.

This system has been submitted to intra- and interobserver reliability assessment16 by a group of spine tumor experts

Indications for En Bloc Resection

The goal of en bloc surgery is to remove the whole tumor with a continuous shell of normal tissue, the margin. Often the tissues surrounding spine tumors are functionally very important and even unresectable. Sometimes nerve root resection leads to significant motor deficit; sometimes a situation arises where a meaningful surgical margin is not possible without transection of the dura or even the spinal cord. These options should be first weighted considering the long-term outcome of oncologically appropriate surgery versus intralesional surgery in each specific conditions.6,17–20 A 2009 systematic review of the literature22 offered evidence (low quality due to the small number of cases reported) that for thoracic and lumbar spine aggressive osteoblastoma, giant cell tumor (Enneking 3), en bloc resection—when anatomically feasible—can be recommended to minimize the risk of local recurrence. En bloc resection should be undertaken for chordoma and chondrosarcoma of the spine, provided wide or marginal margins can be achieved, because it is related to a reduced rate of local control and mortality. In osteosarcomas and Ewing sarcomas of the spine, en bloc resection is associated with better local control and overall survival if associated with a full course of chemotherapy.

The margins are a valid predictor of local and systemic prognosis,6,12,13,17–21 but the possibility to compensate intentional margin transgression with multimodal treatments should be carefully considered. The option of relevant functional sacrifices to target better systemic prognosis must be discussed with the patient. For some patients, the idea of paralysis is not worth considering. Conversely, others might wish to accept paralysis in exchange for possible cure. This is clearly a decision that only the patient should make in conjunction with the counsel of the surgeon. En bloc resections are sometimes proposed also in the treatment of bone metastases in the spine. This indication is open to discussion because the criterion to plan the treatment of metastatic disease is palliation, and risk-to-benefit ratio should always be carefully considered. However, when local control is the primary issue—in solitary metastases from clear cell tumor or colon carcinoma—en bloc resection, if feasible with acceptable risk, may be an option. Bilsky et al.,23 however, in a 2009 systematic literature review, concluded that stereotactic radiosurgery is better than en bloc resection in the treatment of solitary metastases from clear cell carcinoma without epidural extension.

Finally, the specific morbidity of en bloc resections should always be carefully considered.24

Preoperative Planning

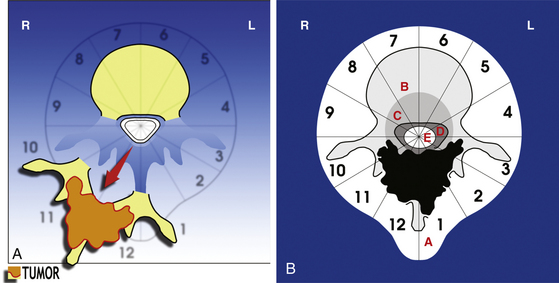

• A posterior resection (Fig. 190-2A) for posteriorly occurring tumor (Fig. 190-2B)

• A posterior-only approach (Fig. 190-3A) for vertebral body tumors not expanding in layer A (Fig. 190-3B)

• A staged approach (see Fig. 190-5A) for vertebral body tumors expanding anteriorly in layer A (see Figure 190-5B).

• A posterior-only or staged sagittal resection (see Fig. 190-6A) for eccentrically located tumors (see Fig. 190-6B).

En bloc excision from a posterior-only approach is possible for vertebral body or eccentric tumors, but it provides an adequate oncologic margin only for tumors without extension into zone A. For all tumors that extend into zone A we recommend a staged posterior and anterior procedure, the anterior release being the first step. It is our opinion that the staged approaches are safer and allow the best oncologic margins.

The techniques of en bloc resections are based on experience collected since 1991, applying and modifying the original techniques by Stener and Roy-Camille.1,2

Operative Techniques

Vertebrectomy

Posterior Approach for Vertebral Body En Bloc Resection

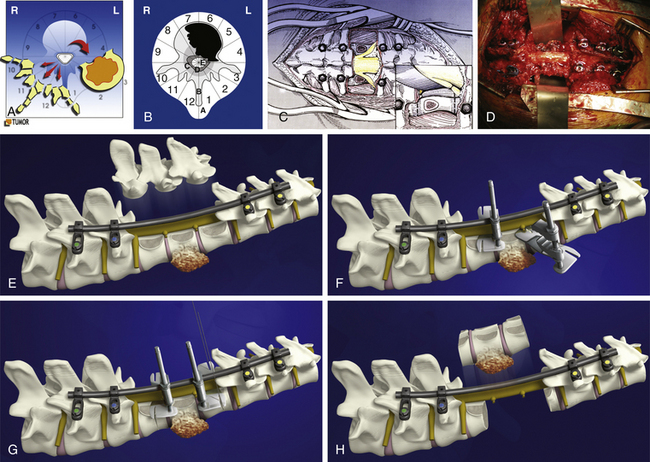

Next, all the posterior elements not involved by tumor are removed (see Fig. 190-3C). This is necessary to allow visualization of the structures anterior to the spinal cord. Obviously, if tumor involves a portion of the posterior elements such as a pedicle, this is left untouched to be removed during the anterior approach. If both pedicles are involved by tumor, it is still possible to remove the tumor en bloc, but it is less likely that an appropriate margin will be achieved. The uninvolved pedicle is removed with a rongeur or high-speed burr.

The dura must be circumferentially released (see Fig. 190-3C), with particular care to section the Hoffman ligament connecting its anterior surface to the posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL). This is a very difficult step when the tumor expands into the epidural space, with a high risk of tumor spread or dural tear.

If the tumor is not expanding in layer A, the en bloc resection may be finalized by a posterior approach, according to the technique proposed by Roy-Camille2 and by Tomita.3 The blunt finger dissection carefully separates the vertebral body from all the anterior elements. The insertion of the diaphragm at T12–L1 and, caudally, the psoas muscle are a difficult obstacle to this release. Once the dissection is performed, malleable elevators replace the fingers (see Fig. 190-3D) and the final step of the en bloc resection can start.

Before beginning the osteotomy, a rod must be secured to the screws on the side opposite to which the vertebra is expected to be removed. This is to prevent any sudden movement if the spine were to fracture through the osteotomy. The resection can be finalized through the disc or through the bone, depending on the tumor extension and the margin required. Roy-Camille proposed to start with a Gigli saw and then conclude with osteotomes; Tomita proposed a thinner saw and designed special tools to protect the dura and the neural elements to be held by the assistant surgeon. One of us (AG) has developed a special device safely connected to one of the rods (Fig. 190-3F and G), facilitating a complete osteotomy by Gigli saw (see Fig. 190-3H) and fully protecting the dura until the specimen is removed (Fig. 190-4).

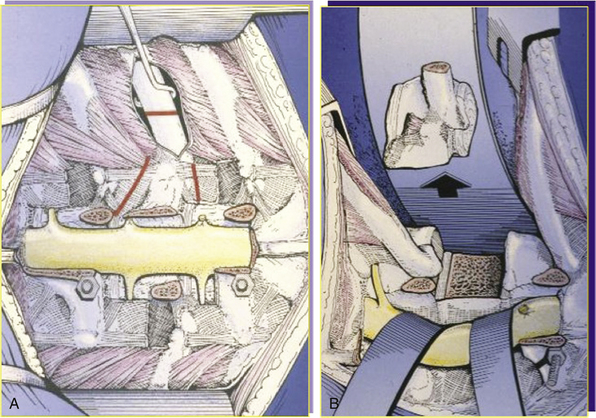

The surgical procedure should include an anterior release (Fig. 190-5A) when the tumor is located at the cervicothoracic, thoracolumbar, or lumbosacral junction or if the tumor mass is expanding anteriorly in layer A (Fig. 190-5B). In the junctional area the anterior release by posterior approach is difficult and risky; if the tumor grows anteriorly, the finger dissection by posterior approach is at high risk of opening the tumor capsule and contaminating the area, preventing local and systemic control. In these cases, the posterior approach ends with the blunt dissection of the lateral aspect of the vertebral body not involved by tumor, if it exists.

Anterior Approach for Vertebral Body En Bloc Resection

The patient is placed on one side in a secure position. An anterolateral skin incision is made. Depending on the level, a thoracotomy, throracolumbar, or retroperitoneal approach (see Fig. 190-5C) is used. Segmental vessels are identified and ligated. A malleable retractor is place between the large vessels and the vertebral body. The tumor mass is identified and a cuff of soft tissue is left to cover it (see Fig. 190-5D), representing the oncologic margin. The posterior incision is reopened. Nearly two thirds of the vertebral body can now be visualized. The blind side is not visualized, but the dissection from the posterior approach has addressed this. The spinal cord is protected.

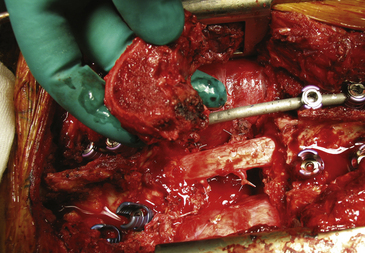

The remaining disc or bone can now be cut or removed. The osteotomy is finished with an osteotome or high-speed burr or Gigli saw. Copious bleeding should be anticipated during osteotomy. The tumor is now delivered en bloc (see Fig. 190-5E).

Reconstruction of the defect may now ensue. The size of the defect can be measured, and an appropriately sized cage may be inserted. Alternatively, a massive allograft (femoral shaft) may be used. The cage or the diaphyseal graft is preferably filled with autogenous bone obtained during the previous exposure. Connection of the anterior reconstructive device by screws to the posterior construct seems to enhance the stability of the whole construct. As a final step, the screw caps are tightened with a torque wrench.

Sagittal Resection

Sagittal resection aims to achieve en bloc resection of a tumor that is growing eccentrically (see Fig. 190-6B). It consists of piecemeal removal of the uninvolved posterior elements to circumferentially release the dura and finalize the resection by a sagittal osteotomy (see Fig. 190-6A). An anterior approach is required when the tumor is growing anteriorly, and a margin of normal tissue must be left under visual control over the tumor, or vital structures must be protected. The dedicated region-specific anterior approach will be necessary to reach the anterior surface of the tumor.

As an alternative, a T-shaped incision combining a posterior midline and a posterolateral incision may be made. In our experience, this second option has been abandoned because it is associated with a higher risk of local complications24

The posterior dissection is performed in the same way as the posterior step of the vertebrectomy, but a cuff of muscle must be left on the transverse process or ribs if a soft tissue mass extends posteriorly (Fig. 190-7A). The uninvolved posterior elements are removed piecemeal. The dura must be exposed on the side opposite the tumor, and the nerve root(s) entering the tumor must be ligated and sectioned. This allows the dural sac to be completely released from the tumor. In the thoracic spine, the rib above and the rib below are removed and the involved ribs are resected at least 2 cm laterally to the maximal tumor extension. In the lumbar spine the soft tissues are cut by cautery 2 cm from the periphery of the tumor mass.

Once the vertical cut has been made, two horizontal cuts are made at each end of the vertical cut to complete the osteotomy. If a sheet of silicone plastic (Silastic) or other material has been left, this protectes the anterior structures. The tumor is finally removed in one piece (see Fig. 190-7B).

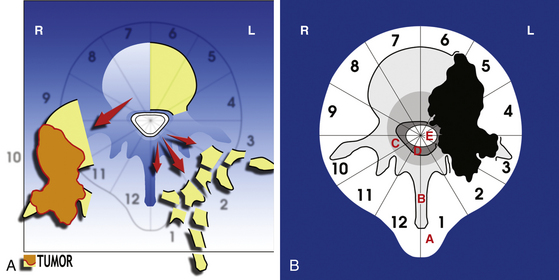

Posterior Resection

The posterior resection (see Fig. 190-2A) requires that both pedicles be free of tumor to obtain an oncologically appropriate margin (see Fig. 190-2B). The patient is placed prone as described earlier. A cuff of normal tissue is left over the tumor in the posterior elements. The spine is exposed subperiosteally above and below this level. The spine must be exposed lateral to the end of the transverse processes in the lumbar spine and lateral to the angle of the ribs in the thoracic spine. The dura must be exposed above and below the level of the tumor. Both pedicles must be exposed without contaminating the field.

The pedicles are transected. There are several ways to do this. As described by Tomita,3 the T saw can be passed around the pedicle with the use of a guide. Once the saw is in place, the bone is cut by using a back and forth motion with the saw. Alternatively, a high-speed burr may be used. We prefer a diamond burr because it is less likely to injure the dura as long as it is kept cool with irrigation. Curve rongeurs may also be used to cut the pedicles. The tumor can be lifted away, and any further soft tissue attachments can be removed bluntly or sharply as required. The spine is reconstructed with posterior instrumentation.

Complications

Complications are very common after en bloc surgery in the spine. We have a team dedicated to the management of spine tumors, and one of three patients in our series sustained a complication.24 The rate of complication goes up with when surgery is for a recurrence or if more than one level is involved. Staged procedures had a higher rate of complication compared to single-stage approaches.24 This likely correlates with the more technically challenging cases because they are most likely to require staged approaches.

Our mortality rate from these surgeries is 2%.13 Unfortunately, these tumors eventually cause the demise of most of these patients if they are not removed. This is a critical point to remember. Local recurrence, metastases, and death are all the enemies of these patients. The surgeon carries a large burden when attempting to remove a spine tumor en bloc. The surgery is morbid and death is a possibility from the surgery itself. The patient and the surgeon must understand this before engaging in these cases.

Summary

Subtotal and total vertebrectomies are technically challenging procedures. They require careful planning. Current staging systems are available to help one organize the surgical plan. Staged procedures are often necessary, and the specific type of resection is dictated by the location of the tumor. We have described the details of three major types of en bloc resections in the thoracic and lumbar spine. The purpose of removing tumors en bloc is to obtain an oncologically sound margin. Complications remain high for these resections, but one must remember that the tumor itself will cause its own set of complications if left alone.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Carlo Piovani for his most valuable assistance for imaging and documentation.

Biagini R., Casadei R., Boriani S., et al. En bloc vertebrectomy and dural resection for chordoma: a case report. 2003. Spine. 2003;28(18):E368-E372.

Boriani S., Weinstein J.N., Biagini R. Spine update. Primary bone tumors of the spine. Terminology and surgical staging. Spine. 1997;22:1036-1044.

Boriani S., Bandiera S., Donthineni R., et al. Morbidity of en bloc resections in the spine. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(2):231-241.

Campanacci M., Boriani S., Savini R. Staging, biopsy, surgical planning of primary spinal tumors. Chir Organi Mov. 1990;75:99-103.

Chan P., Boriani S., Fourney D.R., et al. An assessment of the reliability of the Enneking and WBB classifications for staging of primary spinal tumors by the Spine Oncology Study Group. Spine. 2009;34:384-391.

Currier B.L., Papagelopoulos P.J., Krauss W.E., et al. Total en bloc spondylectomy of C5 vertebra for chordoma. Spine. 2007;32:E294-E299.

Enneking W.F. Muscoloskeletal Tumor Surgery. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1983. 69–122

Fisher C.G., Andersson G.B.J., Weinstein J.N. Summary of management recommandation in spine oncology. Spine. 2009;34:S2-S6.

Keynan O., Fisher C.G., Boyd M.C., et al. Ligation and partial excision of the cauda equina as part of a wide resection of vertebral osteosarcoma: a case report and description of surgical technique. Spine. 2005;30:E97-E102.

Rhines L.D., Fourney D.R., Siadati A., et al. En bloc resection of multilevel cervical chordoma with C-2 involvement. Case report and description of operative technique. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;2:199-205.

Roy-Camille R., Mazel C.H., Saillant G., Lapresle P.H. Treatment of malignant tumor of the spine with posterior instrumentation. In: Sundaresan N., Schmidek H.H., Schiller A.L., Rosenthal D.I. Tumors of the Spine. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1990:473-487.

Stener B., Johnsen O.E. Complete removal of three vertebrae for giant-cell tumour. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1971;53(2):278-287.

Tomita K., Kawahara N., Baba H., et al. Total en bloc spondylectomy. A new surgical technique for primary malignant vertebral tumors. Spine. 1997;22(3):324-333.

1. Stener B, Johnsen OE. Complete removal of three vertebrae for giant-cell tumour. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1971;53(2):278-287.

2. Roy-Camille R, Mazel CH, Saillant G, Lapresle PH. Treatment of malignant tumor of the spine with posterior instrumentation. In: Sundaresan N, Schmidek HH, Schiller AL, Rosenthal DI. Tumors of the Spine. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1990:473-487.

3. Tomita K, Kawahara N, Baba H, et al. Total en bloc spondylectomy. A new surgical technique for primary malignant vertebral tumors. Spine. 1997;22(3):324-333.

4. Enneking WF. Muscoloskeletal Tumor Surgery. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1983. 69–122

5. Campanacci M, Boriani S, Savini R. Staging, biopsy, surgical planning of primary spinal tumors. Chir Organi Mov. 1990;75:99-103.

6. Talac R, Yaszemski MJ, Currier BL, et al. Relationship between surgical margins and local recurrence in sarcomas of the spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2002;397:127-132

7. Fujita T, Kawahara N, Matsumoto T, Tomita K. Chordoma in the cervical spine managed with en bloc excision. Spine. 1992;24:1848-1851.

8. Rhines LD, Fourney DR, Siadati A, et al. En bloc resection of multilevel cervical chordoma with C-2 involvement. Case report and description of operative technique. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;2:199-205.

9. Bailey CS, Fisher CG, Boyd MC, Dvorak MF. En bloc marginal excision of a multilevel cervical chordoma. Case report. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006;4:409-414.

10. Leitner Y, Shabat S, Boriani L, Boriani S. En bloc resection of a C4 chordoma: surgical technique. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:2238-2242.

11. Currier BL, Papagelopoulos PJ, Krauss WE, et al. Total en bloc spondylectomy of C5 vertebra for chordoma. Spine. 2007;32:E294-E299.

12. Biagini R, Casadei R, Boriani S, et al. En bloc vertebrectomy and dural resection for chordoma: a case report. 2003. Spine. 2003;28(18):E368-E372.

13. Keynan O, Fisher CG, Boyd MC, et al. Ligation and partial excision of the cauda equina as part of a wide resection of vertebral osteosarcoma: a case report and description of surgical technique. Spine. 2005;30:E97-E102.

14. American Cancer Society. Facts and Figures 2008. (Accessed December 16, 2011, at http://www.cancer.org/Research/CancerFactsFigures/CancerFactsFigures/cancer-facts-figures-2008, 2008. .)

15. Boriani S, Weinstein JN, Biagini R. Spine update. Primary bone tumors of the spine. Terminology and surgical staging. Spine. 1997;22:1036-1044.

16. Chan P, Boriani S, Fourney DR, et al. An assessment of the reliability of the Enneking and WBB classifications for staging of primary spinal tumors by the Spine Oncology Study Group. Spine. 2009;34:384-391.

17. Hanna SA, Aston WJ, Briggs TW, et al. Sacral chordoma: can local recurrence after sacrectomy be predicted?. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2008;466:2217-2223

18. Bergh P, Kindblom LG, Gunterberg B, et al. Prognostic factors in chordoma of the sacrum and mobile spine: a study of 39 patients. Cancer. 2000;88:2122-2134.

19. Boriani S, Bandiera S, Biagini R, et al. Chordoma of the mobile spine: fifty years of experience. Spine. 2006;31(4):493-503.

20. Boriani S, De Iure F, Bandiera S, et al. Chondrosarcoma of the mobile spine: report on 22 cases. Spine. 2000;25(7):804-812.

21. Fisher CG, Keynan O, Boyd MC, Dvorak MF. The surgical management of primary tumors of the spine. Spine. 2005;30:1899-1908.

22. Fisher CG, Andersson G.B.J., Weinstein JN. Summary of management recommandation in spine oncology. Spine. 2009;34:S2-S6.

23. Bilsky MH, Laufer I, Burch S. Shifting paradigms in the treatment of metastatic spine disease. Spine. 2009;34:S101-S107.

24. Boriani S, Bandiera S, Donthineni R, et al. Morbidity of en bloc resections in the spine. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(2):231-241.