Chapter 180 Management of Penetrating Injuries to the Spine

Penetrating spinal injuries (PSIs) encompass a range of traumatic etiologies, from nonmissile injuries such as knife wounds to high-velocity missile injuries such as rifle shots. Unfortunately, the incidence of PSIs may be increasing.1,2 In addition, there has been a shift from stab wounds to gunshot wounds. There may also be an increase in missile velocity, possibly due to greater civilian access to high-powered weapons.3 Because of the range of injuries, no single management paradigm is applicable to all patients. A lack of randomized trials also makes it harder to make definitive statements regarding optimal management.

The majority of treatment recommendations have resulted from knowledge gained on the battlefield. Traditionally, civilian missile-penetrating traumas have been low-velocity injuries, such as those seen with handguns. However, urban centers are treating more high-velocity injuries similar to military-grade weapons. These high-velocity injuries result in greater concussive injury, tissue damage, and wound contamination.4 In contrast, low-velocity injuries result in localized injury with pathophysiology related to direct trauma, not the concussive element of a supersonic ballistic missile.

Incidence and Classification

Currently, the annual incidence of spinal cord injury (SCI) in the United States is estimated to be 40 per 1 million people, or 12,000 new cases each year5,6 The majority of SCIs are the result of motor vehicle accidents and falls; however, violence (primarily gunshot wounds) results in 15% of injuries. Prior to 1980, violence accounted for 13.3% of SCIs, and this rate peaked in the 1990s at 24.8% before declining to 15.1% in 2005.6 In less developed countries or those with strict gun laws, nonmissile PSIs are proportionally more common.7 According to the National Spinal Cord Injury Database, the mean age of PSI is 29.7 years, with a 4:1 male predominance.8

As with any SCI, PSIs should be described by both anatomic level and degree of neurologic impairment. Anatomically, 20% of injuries are reported in the cervical spine, 50% in the thoracic spine, and 30% in the lumbar spine, which partially reflects the relative lengths of the spine segments.8–13 Approximately 40% of patients are shot in the back, while 19% are shot anteriorly.14 Management and prognosis of injuries is highly dependent on associated injuries, which vary based on trajectory. Associated injuries are reported in 25% of civilian missile (handgun) injuries and 67% of military missile (high-velocity rifle) injuries.2 Injuries to the neck, chest, and abdomen take precedence over spine injury during initial management if vascular or visceral injury threatens patient survival.

It must be determined whether the injury is complete or incomplete and whether it involves the cauda equina. If incomplete or involving the cauda equina, motor, sensory, and sphincter function below the level of injury must be recorded. The American Spinal Injury Association’s International Standards for Neurologic Classification of SCI provides the best assessment of neurologic impairment.15 Patients injured by missiles are more likely to suffer a complete SCI than those suffering from nonmissile injuries. Of patients suffering from missile injuries as reported in the literature, 49% to 83% had complete injuries, 12% to 43% had incomplete injuries, and 17% to 20% had cauda equina injuries.10,14,16–18 Of patients suffering from nonmissile injuries, 21% to 33% had complete injuries and 67% to 79% had incomplete injuries.10–12 Data comparison is limited, because some authors did not consistently categorize injuries to the cauda equina separately.

Clinical Evaluation

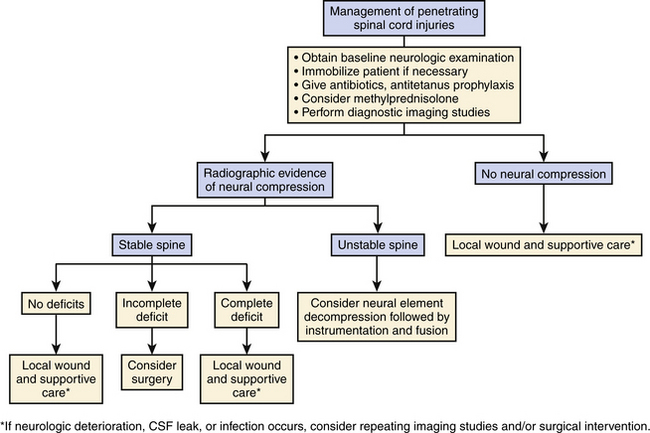

In any PSI, initial evaluation must follow advanced trauma life support (ATLS) guidelines; thus, neurologic examination can occur only after the patient is hemodynamically stable and airway control has been secured. Until the patient is clinically and radiographically cleared, care should be taken to avoid unnecessary movement of the spine. Thus, depending on the situation, a cervical collar, backboard, log-roll, and awake fiberoptic intubation should be considered to avoid iatrogenic neurologic deterioration. Spinal instability is a rare complication of gunshot wounds and is even less common with stab wounds.19 Some centers advocate not immobilizing the patient in the prehospital setting, given that immobilization may complicate or delay care of medically urgent associated injuries.5,20–22

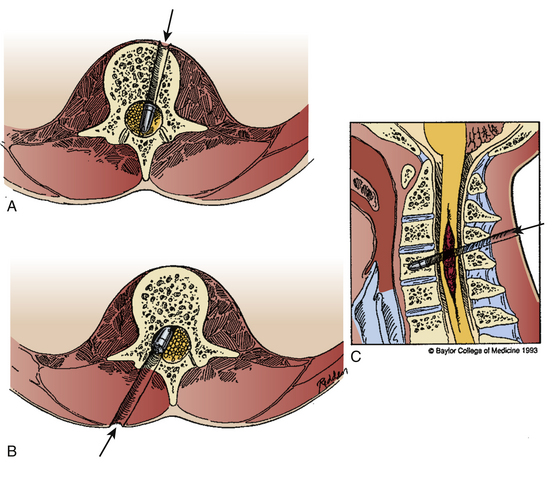

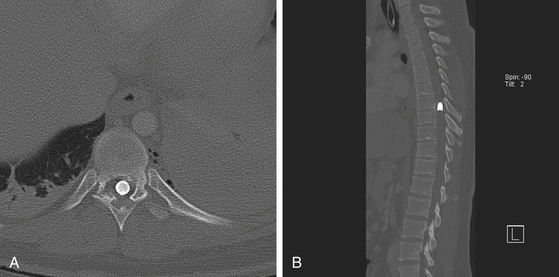

Appropriate imaging studies are needed to fully understand the path of the penetrating object and the resultant anatomic damage, even in asymptomatic patients.23 Plain radiographs may be helpful in identifying metallic fragments, even if an exit wound is clearly seen (Fig. 180-1). Computed tomography (CT) is useful to assess bone damage and canal compromise (both by fracture and by weapon fragments) and to give an initial evaluation of alignment. CT myelogram may also be useful in determining canal and foraminal compromise, or root avulsion injuries. Unfortunately, metal artifact from bullet/knife fragments may make these tests difficult to interpret; yet these same fragments would likely preclude magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI may be useful to assess ligamentous and spinal cord damage, as well as hemorrhage in all compartments (extradural, intradural, and intramedullary) if it is verified that there are no metal fragments. Further tests to determine spinal stability may be needed if clinical or radiographic evidence suggests this may be a problem. Injuries with a “side-to-side” trajectory may be more likely to cause instability.24 Clinical judgment regarding additional tests, including thoracic, abdominal, and vascular imaging studies, should be exercised based on the clinical picture and the suspected trajectory of the penetrating object. In cases of suspected peripheral nerve injury, electromyelography and nerve conduction studies are seldom useful in the acute setting.

Clinical Management

Surgical decompression should be considered in cases of intradural or extradural neural compression from the missile, bone, disc, hematoma, gross contamination, or in-driven foreign bodies. Although PSI may result in spinal instability, this is rare. More relevant is iatrogenic instability resulting from a surgical procedure to decompress the neural elements. Such a situation must be addressed during preoperative planning. Patients with known or planned iatrogenic instability should be considered for stabilization or fusion. Removal of debris or washout of the wound to prevent infection is usually not indicated in missile injuries, because the explosive force of the firing weapon effectively “sterilizes” the bullet. The exception may be stab wounds or cases in which there is gross contamination.25

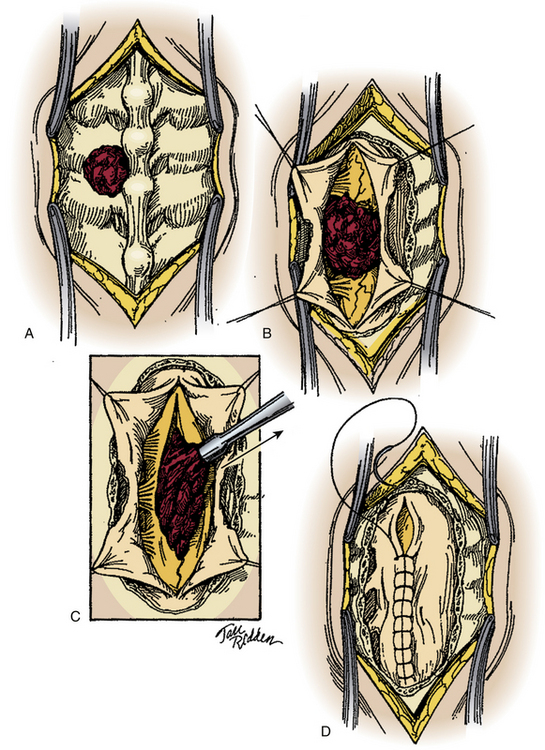

The degree of neurologic compromise and potential for functional recovery is important in determining the aggressiveness of treatment. In patients who are neurologically well, local wound care alone may be appropriate. In patients with complete injuries, surgery is usually not performed unless they have spinal instability or a late complication. In patients with incomplete deficits, surgery in the setting of a compressive lesion may result in functional recovery and should be considered (Fig. 180-2).

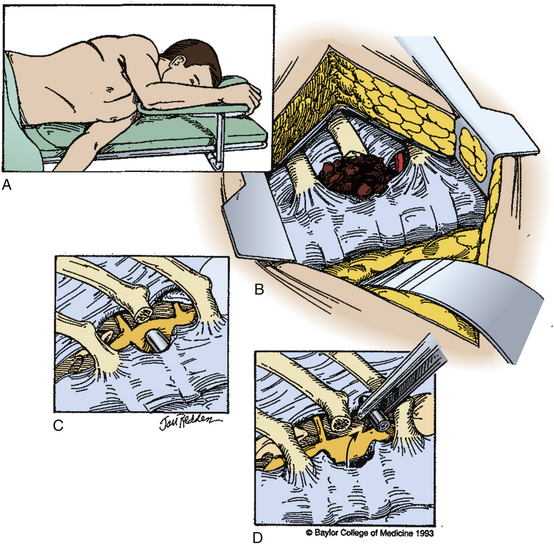

The cauda equina is a special case, as root sparing and recovery is comparable to a peripheral nerve injury (Figs. 180-3 and 180-4). Also, almost all patients enjoy some recovery of nerve root function regardless of management.14 Thus, some practitioners recommend conservative treatment for these injuries,18,26 while others favor surgical intervention.13,16,27 The advantage of surgical intervention is the removal of blood products and necrotic debris, which may decrease the incidence of scarring, arachnoiditis, and chronic pain syndromes.

In some cases, radiographic studies may not explain the neurologic deficit. In high-velocity missile injury, such as that seen from a military rifle bullet, concussive effects can damage neural tissue without the missile penetrating the spinal canal.28–31 In these cases, supportive and local wound care is appropriate. In addition, if a patient develops a progressive deficit without evidence of a new compressive lesion on MRI (e.g., a hematoma or movement of a debris fragment), surgery is not likely to result in improvement.17,32

Involvement of surrounding structures may be important in surgical decision making. Bone and missile fragments in the foramen can result in radicular symptoms. Pain relief and functional recovery may occur if these fragments are removed.33–35 In patients in whom the bowel has been perforated, infections can occur, and in addition to the repair of the bowel perforation, a brief course of antibiotics is recommended. Colonic perforations are at slightly greater risk for infection, thus more aggressive antibiotic coverage is appropriate.36–39 Some authors have advocated débridement of the bone and bullet fragments in the spinal canal if the patient has an associated colonic injury, although we do not favor routine neurosurgical intervention in patients with transperitoneal or transintestinal PSI. In most cases of PSI, broad-spectrum antibiotics and tetanus prophylaxis are the sole indicated therapies.40

Nonsurgical Management

The majority of PSIs require nonsurgical management. In these cases, local wound care and supportive care are sufficient. The wound should be thoroughly cleaned and followed closely for signs of CSF leak or infection, especially if a dural injury has occurred. In addition, prophylactic antibiotics should be given for 24 to 48 hours once the wound has stopped draining. Skin, urinary, excretory, and pulmonary function should be monitored closely, as with any SCI. In addition, patients should begin a comprehensive SCI rehabilitation program as soon as possible. Steroid use in PSI is controversial. Although benefit has been seen in closed SCI, PSI patients were excluded from the National Spinal Cord Injury Study II.41 In retrospective studies, no benefit has been seen to steroid administration, and steroid administration is not recommended.42,43

Surgical Treatment

The goal of surgical treatment is to decompress the neural elements, to repair dural tears to prevent CSF leak, and to stabilize the spine. However, surgery for decompression of the neural elements is seldom beneficial because the injury to the nervous system is most commonly due to the direct mechanical injury or the concussive effect of the penetrating element. Surgery for compressive hematoma is indicated but is an uncommon scenario. Likewise, removal of a projectile may be effective when it causes direct compression to neural elements. CSF leaks are seldom an issue. In our experience, surgery will likely increase the chances of a postoperative incisional CSF leak when compared to nonoperative cases. Therefore, surgical stabilization of an unstable spine is an absolute indication for surgery, but penetrating injuries to the spine seldom result in unstable injuries. Surgical planning should be individualized in each case (Fig. 180-5).

The timing of surgery remains controversial. While data supports early evacuation of hematomas in head injuries to reduce neural injury and optimize recovery,44 this may not be directly applicable to PSI. Early surgery, defined as laminectomy performed within 3 days of injury, has not been clearly shown to improve neurologic function.45 In addition, some authors note a high rate of CSF leaks and infection in cases operated on within 7 days of injury.46 The former is likely due to poor wound closure, and the latter likely results from contamination at the time of injury. This has led some authors to suggest that surgery be delayed beyond 7 days. However, unlike the head injury study described previously, there are no data involving surgeries performed within hours of the injury.

In most cases, a posterior approach to the spine is used and a laminectomy is performed for decompression (Fig. 180-6). If the compressive fragment is located dorsally, and there is no dural incursion, the fragment may be removed once adequate bone has been resected. If intradural exploration is needed, a longitudinal durotomy can be made, or if a tear has occurred, this may be extended to provide adequate exposure of the intradural contents. In the rare circumstance that intramedullary exposure is needed, a longitudinal myelotomy may be performed, preferably midline to reduce injury to the posterior columns. The surgical durotomy should be closed in a watertight fashion, along with all accessible dural tears (Fig. 180-7). Patch grafting may be necessary.

Anterolateral lesions may be approached by the anterior approach in the cervical spine and an anterior, anterolateral, posteroanterolateral, posterolateral, or lateral extracavitary approach in the thoracic and lumbar spine. Unfortunately, ventral dural closure is often quite difficult and may require a complex repair. In cases of dural tears, a lumbar drain should be considered to reduce CSF pressure and divert flow until the defect heals. All wounds should be closed in a multilayer, watertight fashion (Fig. 180-8).

A 5% to 10% complication rate has been reported following the surgical management of PSI.33–35 Complications include infection, CSF fistulas, pseudomeningocele formation, and iatrogenic worsening of neurologic deficit. Spinal instability and delayed myelopathy can also occur. In three series, the complication rate of patients undergoing surgery was much higher, and 16% to 22% of patients developed postoperative meningitis, wound infections, CSF leak, pseudomeningocele, or spinal instability.10,17,47 It may be possible to reduce this with appropriate patient selection, judicious use of antibiotics, and careful surgical technique. More recently, three studies noted a 0% mortality rate.14,33,45

Postoperatively patients should be carefully followed and should begin a standard protocol for SCI. Extubation should occur only if the patient meets all weaning parameters, has an injury level below C5, and does not have head or chest injuries. As with all SCI patients, attention must be paid to pulmonary, urinary, excretory, and skin care. In addition, prophylactic minidose heparin can be considered to prevent deep venous thrombosis.48 Rehabilitation efforts should begin as soon as possible.

Results

Regardless of treatment, prognosis correlates highly with severity of the initial deficit.16,18,47 In patients with immediate, complete deficits following PSI, prognosis is generally poor. For that reason, they are not usually considered surgical candidates. Yashon et al. found no improvement in operated or nonoperated patients with complete deficits immediately after a single bullet wound to the spinal cord above the level of the conus (Fig. 180-9).18 In addition, there is no convincing evidence that surgery improves outcome in patients with incomplete deficits following PSI. Multiple retrospective, nonrandomized studies demonstrated similar rates of improvement between operated and nonoperated patients.10,16–18 However, the possibility that surgery could reduce the risk of arachnoiditis due to the presence of necrotic tissue and blood or reduce the incidence of chronic pain has yet to be determined.

Cauda equina injuries appear to have a more favorable prognosis than other types of PSI, although the degree to which surgery benefits these patients has not been determined. In patients with both complete and incomplete penetrating injuries of the cauda equina, some authors report that 47% to 100% of patients improved following surgery. Even in patients with complete injuries, improvement was seen in 34% of patients following laminectomy and débridement.45 Thus, it is recommended that patients with PSI limited to the cauda equina undergo surgery. However, it is important to document that the fragment or projectile is clearly causing the presenting deficit.

American Spinal Injury Association, Reference Manual of the International Standards for Neurologic Classification of Spinal Cord Injury. Chicago, IL: American Spinal Injury Association; 2003.

Bahebeck J., Atangana R., Mboudou E., et al. Incidence, case-fatality rate and clinical pattern of firearm injuries in two cities where arm owning is forbidden. Injury. 2005;36(6):714-717.

Benzel E., Hadden T., Coleman J. Civilian gunshot wounds to the spinal cord and cauda equina. Neurosurgery. 1987;20:281-285.

Bono C., Heary R. Gunshot wounds to the spine. Spine J. 2004;4(2):230-240.

Brown J.B., Bankey P.E., Sangosanya A.T., et al. Prehospital spinal immobilization does not appear to be beneficial and may complicate care following gunshot injury to the torso. J Trauma. 2009;67(4):774-778.

Carey M. Brain and spinal wounds caused by missiles. In: Long D., editor. Current Therapy in Neurologic Surgery. Toronto: BC Decker; 1985:114-117.

Duz B., Cansever T., Secer H.I., et al. Evaluation of spinal missile injuries with respect to bullet trajectory, surgical indications and timing of surgical intervention: a new guideline. Spine. 2008;33(20):46-53.

Farmer J.C., Vaccaro A.R., Balderston R.A., et al. The changing nature of admission to a spinal cord injury center: violence on the rise. J Spinal Disord. 1998;11(5):400-403.

Heary R., Vaccaro A.R., Mesa J.J., Balderston R.A. Thoracolumbar infections in penetrating injuries to the spine. Orthop Clin North Am. 1996;27(1):69-81.

Klein Y., Cohn S.M., Soffer D., et al. Spine injuries are common among asymptomatic patients after gunshot wounds. J Trauma. 2005;58(4):833-836.

Lipschitz R. Stab wounds of the spinal cord. Handbook Clin Neurol. 1976;25:197-207.

Miller C., Wilkins R., Rengachary S., editors, Penetrating wounds of the spine. Neurosurgery, New York, McGraw Hill, 1985;Vol. 2:1746-1748.

Ohry A., Rozin R. Acute spinal cord injuries in the Lebanon War. Isr J Med Sci. 1984;20:345-349.

Peacock W., Shrosbee R., Key A. A review of 450 stab wounds of spinal cord. S Afr Med J. 1977;51:961-964.

Quigley K., Place H. The role of débridement and antibiotics in gunshot wounds to the spine. J Trauma. 2006;60(4):814-819. discussion 819-820

Ramasamy A., Midwinter M., Mahoney P., Clasper J. Learning the lessons from conflict: pre-hospital cervical spine stabilization following ballistic neck trauma. Injury. 2009;40(12):1342-1345.

Rhee P., Kuncir E.J., Johnson L., et al. Cervical spine injury is highly dependent on the mechanism of injury following blunt and penetrating assault. J Trauma. 2006;61(5):1166-1170.

Shahalie K., Chang D., Anderson J. Nonmissile penetrating spinal injury. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006;4(5):400-408.

Simpson R., Venger B., Narayan R. Penetrating spinal injuries. In: Blaisdell F., Trunkey D. Craniospinal Trauma. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers; 1990:197-212.

Six E., Alexander E., D.K. Jr. Gunshot wounds to the spinal cord. South Med J. 1979;72:699-702.

Stauffer E., Wood R., Kelly E. Gunshot wounds of the spine: the effects of laminectomy. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1979;61A:389-392.

Stover S., Fine P. The epidemiology and economics of spinal cord injury. Paraplegia. 1987;25:225-228.

Thakur R., Khosla V., Kak V. Nonmissile penetrating injuries of the spine. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1991;113:144-148.

Tindall S., Bierbrauer K. Brain and spinal injuries caused by missiles. In: Long D., editor. Current Therapy in Neurologic Surgery. Philadelphia: BC Decker; 1989:187-190.

Vanderlan W., Tew B.E., Seguin C.Y., et al. Neurologic sequelae of penetrating cervical trauma. Spine. 2009;34(24):2646-2653.

Yashon D., Jane J., White R. Prognosis and management of spinal cord and cauda equina bullet injuries in 65 civilians. J Neurosurg. 1970;32:163-170.

1. Farmer J.C., Vaccaro A.R., Balderston R.A., et al. The changing nature of admission to a spinal cord injury center: violence on the rise. J Spinal Disord. 1998;11(5):400-403.

2. Bono C., Heary R. Gunshot wounds to the spine. Spine J. 2004;4(2):230-240.

3. Bahebeck J., Atangana R., Mboudou E., et al. Incidence, case-fatality rate and clinical pattern of firearm injuries in two cities where arm owning is forbidden. Injury. 2005;36(6):714-717.

4. Sights W. Ballistic analysis of shotgun injuries to the central nervous system. J Neurosurg. 1969;31:25-33.

5. Vanderlan W., Tew B.E., Seguin C.Y., et al. Neurologic sequelae of penetrating cervical trauma. Spine. 2009;34(24):2646-2653.

6. Spinal Cord Injury Facts and Figures. www.nscisc.uab.edu/public_content/facts_figures_2009.aspx. [cited 2009 12/2/2009]

7. Thakur R., Khosla V., Kak V. Nonmissile penetrating injuries of the spine. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1991;113:144-148.

8. Stover S., Fine P. The epidemiology and economics of spinal cord injury. Paraplegia. 1987;25:225-228.

9. Fackler M. Ballistic injury. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15:1451-1455.

10. Simpson R., Venger B., Narayan R.. Penetrating spinal injuries, Craniospinal Trauma, F. Blaisdell, D. Trunkey, New York, Thieme Medical Publishers, 1990:197-212

11. Peacock W., Shrosbee R., Key A. A review of 450 stab wounds of spinal cord. S Afr Med J. 1977;51:961-964.

12. Lipschitz R. Stab wounds of the spinal cord. Handbook Clin Neurol. 1976;25:197-207.

13. Carey M. Brain and spinal wounds caused by missiles. In: Long D., editor. Current Therapy in Neurologic Surgery. Toronto: BC Decker; 1985:114-117.

14. Benzel E., Hadden T., Coleman J. Civilian gunshot wounds to the spinal cord and cauda equina. Neurosurgery. 1987;20:281-285.

15. American Spinal Injury Association. Reference Manual of the International Standards for Neurologic Classification of Spinal Cord Injury. Chicago, IL: American Spinal Injury Association; 2003.

16. Six E., Alexander E., D.K. Jr. Gunshot wounds to the spinal cord. South Med J. 1979;72:699-702.

17. Stauffer E., Wood R., Kelly E. Gunshot wounds of the spine: the effects of laminectomy. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1979;61A:389-392.

18. Yashon D., Jane J., White R. Prognosis and management of spinal cord and cauda equina bullet injuries in 65 civilians. J Neurosurg. 1970;32:163-170.

19. Rhee P., Kuncir E.J., Johnson L., et al. Cervical spine injury is highly dependent on the mechanism of injury following blunt and penetrating assault. J Trauma. 2006;61(5):1166-1170.

20. Brown J., Bankey P.E., Sangosanya A.T., et al. Prehospital spinal immobilization does not appear to be beneficial and may complicate care following gunshot injury to the torso. J Trauma. 2009;67(4):774-778.

21. Ramasamy A., Midwinter M., Mahoney P., Clasper J. Learning the lessons from conflict: pre-hospital cervical spine stabilization following ballistic neck trauma. Injury. 2009;40(12):1342-1345.

22. DuBose J., Teixeira P.G., Hadjizacharia P., et al. The role of routine spinal imaging and immobilization in asymptomatic patients after gunshot wounds. Injury. 2009;40(8):860-863.

23. Klein Y., Cohn S.M., Soffer D., et al. Spine injuries are common among asymptomatic patients after gunshot wounds. J Trauma. 2005;58(4):833-836.

24. Duz B., Cansever T., Secer H.I., et al. Evaluation of spinal missile injuries with respect to bullet trajectory, surgical indications and timing of surgical intervention: a new guideline. Spine. 2008;33(20):46-53.

25. Shahalie K., Chang D., Anderson J. Nonmissile penetrating spinal injury. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006;4(5):400-408.

26. Little J., DeLisa J. Cauda equina injury: late motor recovery. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1986;67:45-47.

27. Miller C., Wilkins R., Rengachary S., editors, Penetrating wounds of the spine. Neurosurgery, New York, McGraw Hill, 1985;Vol. 2:1746-1748.

28. Guttmann L. Gunshot injuries of the spinal cord. In: Guttman L., editor. Spinal Cord Injuries: Comprehensive Management and Research. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1976:177-187.

29. Ohry A., Rozin R. Acute spinal cord injuries in the Lebanon War. Isr J Med Sci. 1984;20:345-349.

30. Rautin J., Paavolainen P. Afghan was wounded: experience with 200 cases. J Trauma. 1988;28(4):523-525.

31. Goonewardene S., Mangat K.S., Sargeant I.D., et al. Tetraplegia following cervical spine cord contusion from indirect gunshot injury effects. J R Army Med Corps. 2007;153(1):52-53.

32. Tindall S., Bierbrauer K. Brain and spinal injuries caused by missiles. In: Long D., editor. Current Therapy in Neurologic Surgery. Philadelphia: BC Decker; 1989:187-190.

33. Robertson D., Simpson R. Penetrating injuries restricted to the cauda equina: a retrospective review. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:265-270.

34. Hassin G., Johnstone K., Carr A. Bullet lesion of the cauda equina. JAMA. 1916;66:1001-1003.

35. Isu T., Iwasaki Y., Abe H. Spinal cord and root injuries due to glass fragments and acupuncture needles. Surg Neurol. 1985;23:255-260.

36. Romanick P., Smith T.K., Kopaniky D.R., Oldfield D. Infection about the spine associated with low-velocity missile injury to the abdomen. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1985;67:1195-1201.

37. Kihtir T., Ivatury R.R., Simon R., Stahl W.M. Management of transperitoneal gunshot wounds of the spine. J Trauma. 1991;31:1579-1583.

38. Quigley K., Place H. The role of débridement and antibiotics in gunshot wounds to the spine. J Trauma. 2006;60(4):814-819. discussion 819-820

39. Kumar A., G.W. 2nd, Whittle A. Low-velocity gunshot injuries of the spine with abdominal viscus trauma. J Orthop Trauma. 1998;12(7):514-517.

40. Heary R., Vaccaro A.R., Mesa J.J., Balderston R.A. Thoracolumbar infections in penetrating injuries to the spine. Orthop Clin north Am. 1996;27(1):69-81.

41. Bracken M., Shepard M., Collins W. Methylprednisolone or naloxone treatment after spinal cord injury: 1-year follow-up data. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:23-31.

42. Heary R., Vaccaro A.R., Mesa J.J., et al. Steroids and gunshot wounds to the spine. Neurosurgery. 1997;41(3):576-583.

43. Levy M., Levy M.L., Gans W., et al. Use of methylprednisolone as an adjunct in the management of patients with penetrating spinal cord injury: outcome analysis. Neurosurgery. 1996;39(6):1148-1149.

44. Seelig J., Becker D., Miller J. Traumatic acute subdural hematoma: major mortality reduction in comatose patients treated within four hours. N Engl J Med. 1981;304(25):1511-1518.

45. Cybulski G., Stone J., Kant R. Outcome of laminectomy for civilian gunshot injuries of the terminal spinal cord and cauda equina: review of 88 cases. Neurosurgery. 1989;24:392-397.

46. Benzel E. Penetrating wounds of the spine. In: Rengachary S., Wilkins R. Neurosurgical Operative Atlas. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1991:397-403.

47. Heiden J., Weiss M., Rosenberg A. Penetrating gunshot wounds of the cervical spine in civilians: review of 38 cases. J Neurosurg. 1975;42:575-579.

48. Barnett H., Clifford J. Safety of mini-dose heparin administration for neurosurgical patients. J Neurosurg. 1977;47:27-30.