Chapter 202 Management of Nerve Sheath Tumors Involving the Spine

The true incidence of intradural spinal tumors is unknown as most hospital-based studies have selection bias. In a 10-year population-based study from Iceland from 1954 to 1963, the incidence of intradural spinal tumors was 1.1 per 100,000 people per year.1 Seppala et al.2 estimated the incidence of new spinal schwannomas to be 0.3 to 0.4 per 100,000 people per year. In adults, around half of spinal tumors are IDEM, and roughly half of these are nerve sheath tumors (NSTs). In children, a larger proportion of tumors are intramedullary and a smaller percentage are IDEM.

Classification and Pathology

Schwannomas are well-encapsulated tumors that arise from a single nerve fascicle that displace other uninvolved fascicles by progressive tumor growth. Although the tumor can occur anywhere along the peripheral nerves, favored locations are vestibular part of 8th cranial nerve and dorsal spinal rootlets. Schwannomas are characterized by compact and cellular Antoni A areas with palisading arrangements, called Verocay bodies, and less cellular Antoni B areas that have microcystic changes but no palisading. The neoplastic cells in schwannomas are Schwann cells that stain for S-100, vimentin, and Leu-7.3,4 The tumor rarely contains any functional neural tissue. Secondary changes such as hyalinization, cysts, microhemorrhages, and even mineralization are observed. Variants include ancient schwannomas, cellular schwannomas, and melanotic schwannomas. Schwannomas occur in a sporadic manner as well as well as with certain conditions such as NF-2, schwannomatosis, and Carny’s complex. NF-1 and NF-2 are discussed in more detail below. Schwannomatosis refers to occurrence of multiple schwannomas without other defining features of NF-1 or NF-2.5,6 Patients with Carny’s complex have facial pigmentation, cardiac myxomas, endocrine abnormalities, and melanotic schwannomas, of which 10% may be malignant.7,8

Neurofibromas occur primarily in patients with NF-1 but can also occur sporadically in cutaneous and deep peripheral nerves. They are less well encapsulated than schwannomas and present with more diffuse expansions of the nerve rather than a discrete, dissectable mass. They may have single or multiple fascicles that enter and leave the nerve, making surgical removal almost impossible without sacrificing the peripheral nerve. Often the nerve of origin is nonfunctional on presentation. Plexiform neurofibromas have a predominant intrafascicular histologic growth pattern with redundant loops of expanded nerve fascicles. The presence of axons within the tumor helps distinguish a neurofibroma from a schwannoma. The spindle cells may also stain with S-100 and Leu-7, but less frequently than schwannomas. They lack the densely packed structure like that of Antoni A areas. The presence of mucopolysaccharides in the loose connective tissue also distinguishes these from the schwannomas.

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs) represent 5% to 10% of soft tissue sarcomas. They are malignant neoplasms that usually arise in the presence of a neurofibroma and very rarely a schwannoma. The term currently includes tumors from multiple different classification schemes used in the past such as neurosarcoma, neurofibrosarcoma, and malignant neuroma. The histologic diagnosis is often difficult given their heterogeneity and dedifferentiation. As many as 67% of MNSTs stain for S-100 and they are thought to be composed, at least partially, of cells that differentiate toward Schwann cells. However, the staining patterns of these tumors are somewhat erratic. Around half of these tumors occur in patients with NF-1. Conversely, around 5% of all patients with NF-1 will develop MNSTs.1,9–11 The principal differential diagnosis includes cellular schwannoma, fibrosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, synovial sarcoma, and leiomyosarcoma.12

Neurofibromatosis

The diagnosis of NF-1 is made from presence of two or more of the following seven criteria13,14:

1. Six or more café-au-lait macules over 5 mm in greatest diameter in prepubertal individuals and over 15 mm in greatest diameter in postpubertal individuals

2. Two or more neurofibromas of any type or one plexiform neurofibroma

3. Freckling in the axillary or inguinal regions (Crowe’s sign)

5. Two or more Lisch nodules (iris harmartomas)

6. A distinctive osseous lesion such as sphenoid dysplasia or thinning of long bone cortex with or without pseudoarthrosis

7. A first-degree relative (parent, sibling, or offspring) with NF1 by the above criteria

NF-2 is much less common than NF-1 (1 in 50,000 people). It was first recognized in 1970 as a distinct entity. Cutaneous manifestations are less common than in NF-1, and indeed in older literature, this was referred to as the “central form” of neurofibromatosis compared to the peripheral form, now called NF-1.15 The criteria for diagnosis of NF-2 are met by an individual who satisfies condition 1 or 2 of the following13,14:

Spinal NSTs occur much more frequently in patients with neurofibromatosis. Multiple spinal neurofibromas are seen almost exclusively in patients with NF-1.16 However multiple spinal schwannomas can occur (albeit uncommonly) without neurofibromatosis. NF-1 patients commonly have multiple SNSTs, usually neurofibromas. Occurrence of multiple SNSTs in NF-2 patients is uncommon, but when they occur, they are usually schwannomas.16,17

Tumor Location

Spinal NSTs are almost equally distributed at all levels of the spinal column, but cervical or lumbar predilections have also been described.2,18 In a recent series from Japan, of 149 SNSTs treated between 1980 and 2001, 28 arose from first two cervical roots, 54 from C3–C8 roots, 38 from the thoracic spine, 13 from the conus region, and 43 from the rest of the lumbosacral spinal roots.19 In Seppala’s series, 26% of all schwannomas were cervical, 30% were thoracic, 18% were in the region of conus medullaris, and 21% were lumbosacral.2 In contrast, of 179 SNSTs analyzed by Conti et al., almost half were in the lumbosacral region, one-third in the thoracic region and the rest in the cervical spine.20

Two thirds or more of all SNSTs are purely intradural. The rest are variably divided between pure extradural and dumbbell tumors. In extremely rare cases, purely intramedullary schwannomas have been described. They presumably arise from aberrant Schwann cells or small nerves entering the spinal cord around penetrating spinal arteries.21

In the series by Seppala et al. of 187 spinal schwannomas, 66% were intradural, 13% were extradural, and 19% were both intra- and extra-dural. Analyzing the series further, they found that the cervical tumors had a higher likelihood of being purely extradural. They attributed this to relatively short intradural cervical nerve roots, compared to the thoracic and lumbar roots. This has also been our experience at the University of Miami. In their series, 76% of cervical tumors had an extradural component, while this was the case only in 28% of thoracic tumors and 11% of lumbar tumors.2 Neurofibromas, on the other hand are more commonly extradural or dumbbell shaped. Jinnai and Koyama19 analyzed 149 cases of SNSTs and found that strictly intradural tumors comprise only 8% of tumors of the first two cervical roots. The percentage of these tumors increased gradually from the high cervical region to the thoracolumbar region, where it was more than 80%. In contrast, the percentage of strictly extradural tumors gradually decreased from the cervical to lumbar region. They also attributed these changes in the growth pattern to anatomic features of the spinal nerve roots, which have a longer intradural component at the more caudal portion of the spinal axis.19

Clinical Presentation

Spinal NSTs occur equally in males and females. They usually peak in the fourth to fifth decades and are uncommon in children and the elderly.2 About half of all IDEMs in adults are nerve sheath tumors compared to less than 5% in children. Most of the spinal tumors in children tend to be intramedullary.22

Imaging Features

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the imaging modality of choice. Schwannomas are usually isointense (75%) or hypointense (25%) on T1- and hyperintense on T2-weighted images with intense contrast enhancement.23 Cystic changes may sometimes be seen in 20% to 40% of cases. MRI defines the anatomy in all three planes and reveals the tumor relationship to the spinal cord, nerve roots, and the surrounding structures. These tumors usually remodel the surrounding structures, expanding in whatever space available to them. Dumbbell lesions are more common in the lower spine than in the cervical spine.24 Because of space constraints, the dumbbell tumors are smaller within the canal but can expand to large sizes in the relatively open spaces of the retroperitonium or the chest. Infiltration and invasion of surrounding structures are not seen unless there is a malignant change.

Plain x-rays are no longer universally obtained in patients suspected of having SNSTs. They may demonstrate enlarged neural foramen, increased interpedicular distance, scalloping of posterior vertebral bodies, and thinning of pedicles. These nonspecific changes are due to the slow growth of the tumors over time causing bony remodeling. Some of these changes can be seen in NF-1 even without neurofibromas.25

Surgical Indications

Spinal NST is a surgical disease, and surgical excision is recommended in a majority of patients. Conservative management is usually reserved for patients who are very poor surgical candidates, are asymptomatic, or have minimally symptomatic lesions with neurofibromatosis and multiple tumors. In all sporadic cases, surgery is indicated for symptomatic lesions or large/growing asymptomatic lesions. This is because in most cases, the surgery is fairly straightforward for neurosurgeons adept in microsurgical techniques and there is no guarantee of improvement in neurologic symptoms after they occur.

Radiation therapy or chemotherapy traditionally has no role in the management of benign SNSTs. More recently, fractionated stereotactic radiation with Cyberknife (Accuray, Sunnyvale, CA) has been shown to be helpful in these cases. In 2006, Dodd et al. published their results on treatment of 51 patients with Cyberknife. Of the 28 patients with more than 2 years follow-up, all had either stable (61%) or smaller (39%) tumors. One patient had radiation-induced myelopathy and three patients out of 51 needed surgery within 1 year of treatment due to worsening disease.26 The intermediate term follow-up had similar results.27 Cyberknife treatment is an alternative to surgery in patients who are poor surgical candidates, have multiple tumors with neurofibromatosis, or have recurrent progressive disease that is not amenable to safe resection. Surgery still remains the first line of treatment in these tumors. In cases of malignant spinal NSTs (MSNSTs), postoperative radiation is employed for local disease control. Chemotherapy is not very helpful in most of these cases.28 Outcome in malignant cases is very poor despite aggressive therapy.

Surgical Approaches

Intradural Tumors

Most SNSTs are intradural. Almost all of these tumors can be removed by a posterior approach, including those with a significant ventral component or small part going into the neural foramen. For large midline ventral tumors, anterior corpectomy and reconstruction comprise an option but this approach is challenging and very rarely needed.29 Standard techniques of laminectomy and microsurgery are employed for removal of the vast majority of these tumors. For cervical tumors with spinal cord compression, awake fiberoptic intubation is preferred. We monitor somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEPs) in both upper and lower extremities along with motor-evoked potentials (MEPs) during the surgery to recognize early threats to the spinal cord. Electrodes are placed by the neuromonitoring team after intubation, and baseline recordings are obtained. All our cases are implemented in prone position. A radiolucent table top is used in cases where instrumentation is being planned. We prefer Mayfield three-point skull fixation during the prone position to avoid any kind of pressure on the face or eyes. The patient is turned into prone position carefully with “spine precautions.” Adequate padding is confirmed at all bony prominences and genitals. The table is positioned in a way that the eyes are above the heart to avoid ovular venous congestion. It also enhances venous drainage in cervical operations. Care is also taken to free the lower chest and abdomen from any pressure to promote good respiratory excursions and prevent engorgement of epidural venous plexus.

The importance of correct localization cannot be overemphasized. The incision site is marked before scrubbing the patient using fluoroscopy and again confirmed before laminectomy. In children, we prefer laminoplasty over laminectomy. Yasuoka et al.30 found 46% incidence of spinal column deformity if laminectomies were done in children less than 15 years of age, compared to 6% in patients aged 15 to 25 years and 0% in those older than 25 years. A midline vertical incision is then made over the appropriate site, and paraspinal muscles are dissected off the spinous processes and lamina in a subperiosteal manner. In cervical or thoracic spine, the laminectomy is done very carefully to prevent any pressure on the cord, particularly if there is pre-existing spinal cord compression. We prefer a combination of high-speed drill, Leksell rongeurs, and/or Kerrison (2 or 3 mm) punches for removing the lamina, taking care not to put the instruments under the lamina. The laminectomy should extend both above and below the tumor to expose the tumor entirely. Meticulous extradural hemostasis is important at this stage as a decrease in epidural pressure on opening the dura and egress of CSF will increase epidural bleeding, making the operation messy.

We use an operating microscope at this time, although the dural opening could be done under microscope as well, depending on the surgeon’s preference. The technique of tumor removal depends on the size, consistency, vascularity, and adhesions of the tumor to the surrounding rootlets. There is usually a very good plane between the tumor and the spinal cord, but larger tumors may be stuck to the anterior rootlets. Schwannomas usually arise from one or more nerve fascicles in the dorsal rootlets. Effort should be made to separate these fascicles from the tumor by developing a plane between the tumor and the rootlets using a combination of Rhoton microdissecting instruments and a No. 6 Penfield dissector. Smaller tumors can usually be excised en toto, whereas larger tumors need internal decompression and piecemeal removal. Every effort should be made to prevent retraction or pressure on the cord itself beyond that already exerted by the growing tumor.31

Dumbbell or Extradural Tumor

For the cervical spine, the relationship of the tumor to the vertebral artery is important in the planning of any surgical strategy. MRA (in addition to the MRI) may be helpful in this regard to further define the anatomy. Smaller tumors can be dealt with using a partial or complete foraminotomy and facetectomy. For tumors of the C1 root, a small craniotomy going anteriorly up to the sigmoid sinus is needed for proper exposure. Fusion is not needed if the atlantoaxial and atlanto-occipital joints have been preserved. An extreme lateral approach has also been described for intradural tumors in the upper cervical spine and foramen magnum by several authors.32,33 A combined anterior and lateral with fusion approach has been described by Hakuba et al. for tumors of the subaxial cervical spine.34 A combined, staged anterior and posterior approach to these tumors is also an option, as is a combined postero-posterolateral approach.35,36 Some authors have proposed classification systems to determine the best surgical strategy to deal with the dumbbell tumors in the cervical spine based on the extent of the tumor in different anatomic planes.37–39

Large dumbbell tumors of the thoracic spine can have significant masses in the chest with a mass effect on the intrathoracic organs. We prefer to stage the surgery, first removing the intraspinal part using a standard posterior approach described above, and then using an anterolateral approach with the help of a thoracic surgeon to address the thoracic tumor. The second surgery could be performed via a thoracotomy or a posterolateral extracavitary approach, many variations of which have been described.40–43 Posterolateral approaches utilizing a costo-transversectomy that were initially developed for tuberculosis of the spine have the advantage of providing excellent exposure to intradural, intraforaminal, and extraforaminal parts of the tumor. They also do not violate the pleural space, minimizing the need for a chest tube and hence of a CSF-pleural fistula in the event of a CSF leak. An interesting new development is the combination of endoscopic thoracoscopy approaches for removal of the extraforaminal component. This has the potential to decrease the morbidity associated with a thoracotomy and its use will increase over time.41,44,45

A similar posterior approach strategy followed by a separate flank incision and retroperitoneal approach is typically used for large lumbar schwannomas. The lumbosacral plexus lies within the psoas muscle, and the tumor has to be carefully dissected free of any plexus elements within the muscle. Posterolateral approaches in the lumbar spine are hindered by large paraspinal muscles at this level and the presence of the iliac crest. Most sacral tumors are taken care of by posterior approaches. Larger tumors may need a staged surgery. Bladder and bowel continence is usually preserved if S2 to S4 roots are intact on at least one side.

To Fuse or Not?

The vast majority of IDEMs operated via the posterior approach do not require fusion. The fear of destabilizing the spine should not prevent us from obtaining the necessary bony exposure. Judicious removal of bone is always better than any retraction on the neural elements, especially the spinal cord that is chronically compressed and already compromised. In cases with dumbbell tumors or extradural tumors being operated from a posterior or posterolateral approach, removal of one third or even half of the facet joint complex is well tolerated. However, if more bone is removed for adequate tumor exposure, instrumented fusion should be considered. In case of ventrally situated tumors where drilling of the pedicles is necessary in addition to facetectomy, instrumented fusion will be necessary and should be planned in advance. A pre-existing kyphosis or lysthesis at the operated level, underlying spinal instability or a malignant tumor needing more extensive bony exposure for radical surgery would also need fusion.46 Most surgeons would perform the fusion during the same sitting if it is needed; however, if the surgeon is not sure about spinal stability, doing it as a separate operation is an option as well.

Surgery in Neurofibromatosis Cases

Most of the tumors in patients with NF-1 are neurofibromas rather than schwannomas. This makes complete removal without sacrifice of the involved nerve root almost impossible. In the thoracic levels (except T1), the roots can be sacrificed if needed but doing so in cervical or lumbar regions obviously leads to focal weakness and numbness. This is not well tolerated by these patients as many of them are either already weak or are at risk of developing more weakness in future due to progression of other tumors or the development of new tumors. Neurofibromatosis significantly affects the recurrence rates of schwannomas. Klekamp and Samii47 had a 39% recurrence rate in patients with NF and 11% in those without.

Malignant Nerve Sheath Tumors

As discussed above, these malignant tumors can occur sporadically, as a long-term complication of radiation therapy or in association with NF. They spread widely, often infiltrating the surrounding tissues and traveling up and down the involved nerves, and often reaching the central nervous system, which often limits their complete resection.48,49 The aim of surgery is mostly palliative due to very aggressive behavior: preservation of neurologic function, relief of pain, and cytoreduction. Often extensive radical surgery is needed to achieve these goals. In many cases, it may mean total vertebrectomy or other radical procedures along with instrumented fusion. Postoperative, external beam radiation therapy is used for local disease control. The outcome of MSNST is very poor with median survival in months to years.49,50 Aggressive gross total resection can prolong survival in a minority of these patients, justifying radical surgery in these cases, but overall the outcome is dismal. Mean survival was less than a year in a modern series from Germany.49

Complications and Postoperative Care

The two major complications are CSF leakage and neurologic deficits. In case of inadequate dural closure, we place a prophylactic lumbar drain at the end of surgery in the operating room to decrease intrathecal pressure and allow tissues to heal. CSF is generally drained at a rate of 5 to 15 cc/hr, along with forced recumbency for a period of 4 to 5 days. In patients with postoperative CSF leakage in whom a lumbar drain was not placed immediately after surgery, the wound is reinforced with suture, followed by a pressure dressing, lumbar drainage, and recumbent position. We use a cervical drain placed in the lateral C1–C2 cistern under direct fluoroscopic guidance in patients with extensive lumbar surgery, and have demonstrated its safety and efficacy in these cases.51 If the leakage persists after 4 to 5 days, the wound is re-explored. Neurologic deficits related to nerve root damage are somewhat expected after this surgery, but if there is evidence of spinal cord compression, emergent MRI should be done to rule out an epidural hematoma.

In general, the overall complication rate is low and the results are good. The symptoms related to spinal cord compression usually improve but not those related to nerve root involvement. In Seppala’s series of 187 spinal schwannomas, 90% of patients had gross total resection. There was an improvement in radicular motor deficits from 30% to 22%, but a slight increase in radicular sensory symptoms from 25% to 28% of the patients. There were 11 recurrences, only 2 of which needed reoperations. Surgical mortality was 1.5%, and the overall complication rate was 10%; 5% of patients lost ambulation and 10% had worsening in bladder function. Overall, 78% of patients improved postoperatively (7% were worse), 81% of nonambulatory patients regained ambulation, and 63% had improvement in bladder function.2 Spinal neurofibromas fare somewhat worse. In a series on 32 spinal neurofibromas, 70% improved postoperatively (16% were worse); there were 4 recurrences and 2 of these needed reoperations.52 In a recent series from Italy including 179 spinal schwannomas with mean follow-up duration of 17.5 years, 76% had complete recovery in symptoms, 17% had improvement in symptoms, 4% had stable symptoms, and less than 1% had worsening in symptoms. The 2 deaths were patients with NF.

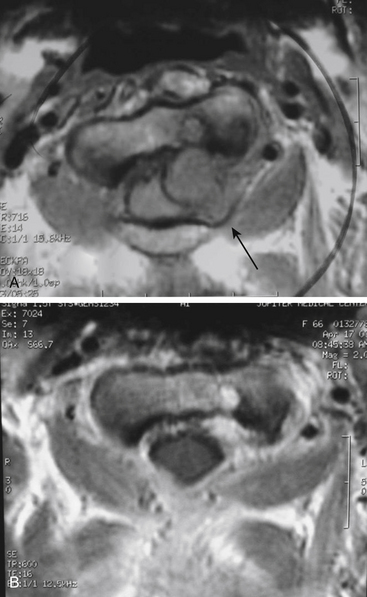

Case 1

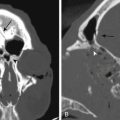

A 66-year-old woman presented with left occipital pain and numbness. She then developed progressive decline in motor function with gait instability and difficulty with fine motor skills of fingers, more on the left than the right. She also developed generalized numbness of the body and hyperreflexia and clonus. MRI revealed an intradural-extramedullary lesion at the C2 level on the left side causing spinal cord compression (Fig. 202-1). She underwent a C1–C2 laminectomy with complete removal of the tumor without any instrumentation or fusion. During the surgery, the exposure was extended laterally beyond the facet joints of C2 and C3 to expose the vertebral artery above and below C1. The integrity of the C2–C3 facet joint was meticulously preserved to prevent any instability. The tumor was first internally debulked and then removed piecemeal. The left C2 root, from which the tumor was emanating, was sacrificed. The completeness of removal was confirmed by intraoperative ultrasound at the beginning and end of the procedure. This patient did not need any stabilization procedure on long-term follow-up. When careful attention is paid to maintaining facet joint integrity and the extent of bony removal, instability can be prevented even in mainly laterally situated tumors with small extensions into the neural foramina.

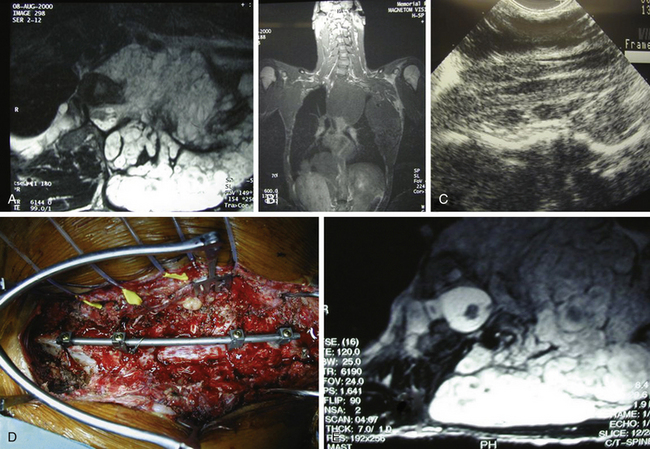

Case 2

A 19-year-old male with a known history of NF-1 presented with rapidly progressive myelopathy referable to thoracic cord compression at the T3–T4 level and partial Brown-Séquard syndrome with severe left leg weakness and dense right leg sensory loss. He had multiple large neurofibromas in his body. A spinal MRI revealed a large left-sided plexiform neurofibroama in the thorax with thoracic spine scoliosis (apex to the right) and significant circumferential spinal cord compression at the T3–T4 level that was more severe on the left side (Fig. 202-2A and B). The cord was crescent-shaped and had myelomalacic signal changes at the level of maximum compression. The tumor was extending into the paraspinal muscles and the subcutaneous tissues. The patient also underwent a preoperative angiogram that revealed the artery of Adamkiewicz originating on the left at the L2 level; there were no embolizable feeders to the tumor. He had undergone a biopsy earlier that revealed a neurofibroma with no malignant change. He underwent a T2–T4 laminectomy in prone position on a four-poster frame. We also removed the pedicles to get the lateral extent of the spinal tumor. After we removed the circumferential epidural tumor, we did an intraoperative ultrasound that revealed that the tumor was primarily extradural and more tumor was left ventrally, causing spinal cord compression. To get ventral access, we double ligated and cut the left T3 nerve root and removed additional tumor mass. A repeat ultrasound revealed that the spinal cord was decompressed (Fig. 202-2C). Because of extensive bone removal and preexisting scoliosis, we performed elective spinal fusion without deformity correction, which was done using C7–T1 to T6–T7 laminar hooks and rod, and T5 laminar wires with allograft and iliac crest autograft (Fig. 202-2D). His upper thoracic pedicles were too atretic to insert pedicle screws. Postoperatively, his left leg power improved by one grade and he was able to walk with support in a Yale brace. MRI revealed that the spinal cord was free of any compression (Fig. 202-2E). The extensive thoracic tumor within the pleural cavity was followed with serial MRI scans.

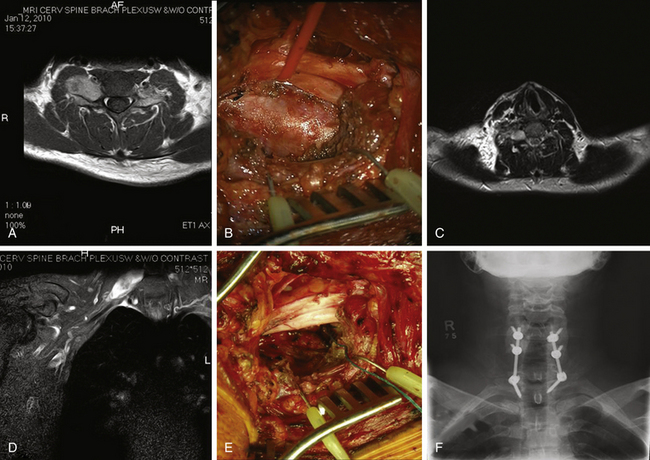

Case 3

A 26-year-old man presented with NF-1 and an extensive past medical history of surgery for benign and MNSTs. He had also undergone chemotherapy and radiation therapy for some of these peripheral nerve tumors. He was referred to us for an enlarging right C6–C7 neural foramen tumor with progressive arm pain and focal weakness (Fig. 202-3A and B). Because of the extension of the tumor into the right middle trunk of the brachial plexus, it was thought that a two-stage procedure would be best for complete removal. The first stage involved a supraclavicular incision, retraction of C5–C6 roots, and upper trunk and partial division of anterior scalene muscle. A well-encapsulated tumor was seen emanating from the C7 root and middle trunk (Fig. 202-3C). It was debulked using intraoperative nerve monitoring to save any motor fascicles, and then was carefully peeled off the nerve as proximally as possible (Fig. 202-3D). The intraoperative biopsy revealed many mitotic figures per high-power field, suggesting a more malignant process. The postoperative MRI revealed a small amount of residual tumor within the foramen as expected (Fig. 202-3F). The second stage was performed via C6–C7 laminectomy and complete facetectomy to remove the foraminal tumor after confirmation of a malignant pathology. The extradural tumor along the right C7 root was removed after complete right C6–C7 facetectomy, supplemented by C5–T1 posterior instrumented fusion (Fig. 202-3F).

Conclusions

Spinal nerve sheath tumors (schwannomas and neurofibromas) are uncommon and can present either sporadically or in association with NF-1 or NF-2. They have no gender predilection and are most common in the middle age. They usually present with radicular symptoms or features of spinal cord compression. Diagnosis is best made with MRI with and without contrast. Surgical treatment is advised for all symptomatic patients and asymptomatic patients with large or enlarging tumors. The outcome of surgery is usually good, with a relatively low complication rate. Malignant nerve sheath tumors have a poor prognosis despite radical surgery.

Amin A., Saifuddin A., Flanagan A., et al. Radiotherapy-induced malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor of the cauda equina. Spine. 2004;29:E506-E509.

Anghileri M., Miceli R., Fiore M., et al. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: prognostic factors and survival in a series of patients treated at a single institution. Cancer. 2006;107:1065-1074.

Conti P., Pansini G., Mouchaty H., et al. Spinal neurinomas: retrospective analysis and long-term outcome of 179 consecutively operated cases and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2004;61:34-43. discussion 44

Ducatman B.S., Scheithauer B.W., Piepgras D.G., et al. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. A clinicopathologic study of 120 cases. Cancer. 1986;57:2006-2021.

Farhat H.I., Elhammady M.S., Levi A.D., Aziz-Sultan M.A. Cervical subarachnoid catheter placement for continuous cerebrospinal fluid drainage: a safe and efficacious alternative to the classic lumbar cistern drain. Neurosurgery. 2011;68:52-56. discussion 56

Ferner R.E., Gutmann D.H. International consensus statement on malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors in neurofibromatosis. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1573-1577.

Grillo H.C., Ojemann R.G., Scannell J.G., Zervas N.T. Combined approach to “dumbbell” intrathoracic and intraspinal neurogenic tumors. Ann Thorac Surg. 1983;36:402-407.

Hajjar M.V., Smith D.A., Schmidek H.H. Surgical management of tumors of the nerve sheath involving the spine. In: Schmidek H.H., editor. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2000:1843-1853.

Holland K., Kaye A.H. Spinal tumors in neurofibromatosis-2: management considerations—a review. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16:169-177.

Huang J.H., Simon S.L., Nagpal S., et al. Management of patients with schwannomatosis: report of six cases and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2004;62:353-361. discussion 361

Jiang L., Lv Y., Liu X.G., et al. Results of surgical treatment of cervical dumbbell tumors: surgical approach and development of an anatomic classification system. Spine. 2009;34:1307-1314.

Jinnai T., Koyama T. Clinical characteristics of spinal nerve sheath tumors: analysis of 149 cases. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:510-515. discussion 510-515

Klekamp J., Samii M. Surgery of spinal nerve sheath tumors with special reference to neurofibromatosis. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:279-289. discussion 289-290

MacCollin M., Chiocca E.A., Evans D.G., et al. Diagnostic criteria for schwannomatosis. Neurology. 2005;64:1838-1845.

Mrugala M.M., Batchelor T.T., Plotkin S.R. Peripheral and cranial nerve sheath tumors. Curr Opin Neurol. 2005;18:604-610.

National Institutes of Health. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: neurofibromatosis. Bethesda, Md., USA, July 13–15, 1987. Neurofibromatosis. 1988;1:172-178.

NIH Consensus. Neurofibromatosis: conference statement. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:575-578.

Ozawa H., Kokubun S., Aizawa T., et al. Spinal dumbbell tumors: an analysis of a series of 118 cases. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;7:587-593.

Payer M., Radovanovic I., Jost G. Resection of thoracic dumbbell neurinomas: single postero-lateral approach or combined posterior and transthoracic approach? J Clin Neurosci. 2006;13:690-693.

Sen C.N., Sekhar L.N. An extreme lateral approach to intradural lesions of the cervical spine and foramen magnum. Neurosurgery. 1990;27:197-204.

Seppala M.T., Haltia M.J., Sankila R.J., et al. Long-term outcome after removal of spinal neurofibroma. J Neurosurg. 1995;82:572-577.

Seppala M.T., Haltia M.J., Sankila R.J., et al. Long-term outcome after removal of spinal schwannoma: a clinicopathological study of 187 cases. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:621-626.

Watson J.C., Stratakis C.A., Bryant-Greenwood P.K., et al. Neurosurgical implications of Carney complex. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:413-418.

Woodruff J.M., Selig A.M., Crowley K., Allen P.W. Schwannoma (neurilemoma) with malignant transformation. A rare, distinctive peripheral nerve tumor. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:882-895.

Yuksel M., Pamir N., Ozer F., et al. The principles of surgical management in dumbbell tumors. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1996;10:569-573.

1. Guomundsson K.R. A survey of tumors of the central nervous system in Iceland during the 10-year period 1954-1963. Acta Neurol Scand. 1970;46:538-552.

2. Seppala M.T., Haltia M.J., Sankila R.J., et al. Long-term outcome after removal of spinal schwannoma: a clinicopathological study of 187 cases. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:621-626.

3. Requena L., Sangueza O.P. Benign neoplasms with neural differentiation: a review. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:75-96.

4. Sangueza O.P., Requena L. Neoplasms with neural differentiation: a review. Part II: malignant neoplasms. Am J Dermatopathol. 1998;20:89-102.

5. Huang J.H., Simon S.L., Nagpal S., et al. Management of patients with schwannomatosis: report of six cases and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2004;62:353-361. discussion 361

6. MacCollin M., Chiocca E.A., Evans D.G., et al. Diagnostic criteria for schwannomatosis. Neurology. 2005;64:1838-1845.

7. Carney J.A. Psammomatous melanotic schwannoma. A distinctive, heritable tumor with special associations, including cardiac myxoma and the Cushing syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14:206-222.

8. Watson J.C., Stratakis C.A., Bryant-Greenwood P.K., et al. Neurosurgical implications of Carney complex. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:413-418.

9. Anghileri M., Miceli R., Fiore M., et al. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: prognostic factors and survival in a series of patients treated at a single institution. Cancer. 2006;107:1065-1074.

10. Ferner R.E., Gutmann D.H. International consensus statement on malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors in neurofibromatosis. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1573-1577.

11. Woodruff J.M., Selig A.M., Crowley K., Allen P.W. Schwannoma (neurilemoma) with malignant transformation. A rare, distinctive peripheral nerve tumor. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:882-895.

12. Hajjar M.V., Smith D.A., Schmidek H.H. Surgical management of tumors of the nerve sheath involving the spine. In: Schmidek H.H., editor. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2000:1843-1853.

13. National Institutes of Health. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: neurofibromatosis. Bethesda, Md., USA, July 13-15, 1987. Neurofibromatosis. 1988;1:172-178.

14. National Institutes of Health. NIH Consensus: neurofibromatosis: conference statement. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:575-578.

15. Hajjar M.V., Smith D.A., Schmidek H.H. Surgical management of tumors of the nerve sheath involving the spine. In: Schmidek H.H., editor. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2000:1843-1853.

16. Brisman M., Perin N., Post K. Excision of spinal neurofibromas. In: Kaye A., Black P. Operative Neurosurgery. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2000:1937-1946.

17. Holland K., Kaye A.H. Spinal tumors in neurofibromatosis-2: management considerations—a review. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16:169-177.

18. Hori T., Takakura K., Sano K. Spinal neurinomas—clinical analysis of 45 surgical cases. Neurol Med-Chir. 1984;24:471-477.

19. Jinnai T., Koyama T. Clinical characteristics of spinal nerve sheath tumors: analysis of 149 cases. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:510-515. discussion 510-515

20. Conti P., Pansini G., Mouchaty H., et al. Spinal neurinomas: retrospective analysis and long-term outcome of 179 consecutively operated cases and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2004;61:34-43. discussion 44

21. Mason T.H., Keigher H.A. Intramedullary spinal neurilemmoma: case report. J Neurosurg. 1968;29:414-416.

22. Constantini S., Miller D.C., Allen J.C., et al. Radical excision of intramedullary spinal cord tumors: surgical morbidity and long-term follow-up evaluation in 164 children and young adults. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:183-193.

23. Hu H.P., Huang Q.L. Signal intensity correlation of MRI with pathological findings in spinal neurinomas. Neuroradiology. 1992;34:98-102.

24. Kivrak A.S., Koc O., Emlik D., et al. Differential diagnosis of dumbbell lesions associated with spinal neural foraminal widening: imaging features. Eur J Radiol. 2009;71:29-41.

25. Tonsgard J.H. Clinical manifestations and management of neurofibromatosis type 1. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2006;13:2-7.

26. Dodd R.L., Ryu M.R., Kamnerdsupaphon P., et al. CyberKnife radiosurgery for benign intradural extramedullary spinal tumors. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:674-685. discussion 674-685

27. Murovic J.A., Gibbs I.C., Chang S.D., et al. Foraminal nerve sheath tumors: intermediate follow-up after cyberknife radiosurgery. Neurosurgery. 2009;64:A33-A43.

28. Mrugala M.M., Batchelor T.T., Plotkin S.R. Peripheral and cranial nerve sheath tumors. Curr Opin Neurol. 2005;18:604-610.

29. O’Toole J.E., McCormick P.C. Midline ventral intradural schwannoma of the cervical spinal cord resected via anterior corpectomy with reconstruction: technical case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:1482-1485. discussion 1485-1486

30. Yasuoka S., Peterson H.A., MacCarty C.S. Incidence of spinal column deformity after multilevel laminectomy in children and adults. J Neurosurg. 1982;57:441-445.

31. Uchida K., Nakajima H., Sato R., et al. Microsurgical intraneural extracapsular resection of neurinoma around the cervical neuroforamen: a technical note. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2009;52:271-274.

32. George B., Dematons C., Cophignon J. Lateral approach to the anterior portion of the foramen magnum. Application to surgical removal of 14 benign tumors: technical note. Surg Neurol. 1988;29:484-490.

33. Sen C.N., Sekhar L.N. An extreme lateral approach to intradural lesions of the cervical spine and foramen magnum. Neurosurgery. 1990;27:197-204.

34. Hakuba A., Komiyama M., Tsujimoto T., et al. Transuncodiscal approach to dumbbell tumors of the cervical spinal canal. J Neurosurg. 1984;61:1100-1106.

35. Habal M.B., McComb J.G., Shillito J.Jr., et al. Combined posteroanterior approach to a tumor of the cervical spinal foramen. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1972;37:113-116.

36. Oruckaptan H.H., Gurcay O. Combined posterior and posterolateral one-stage removal of a giant cervical dumbbell schwannoma. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1999;30:102-107.

37. Asazuma T., Toyama Y., Maruiwa H., et al. Surgical strategy for cervical dumbbell tumors based on a three-dimensional classification. Spine. 2004;29:E10-E14.

38. Jiang L., Lv Y., Liu X.G., et al. Results of surgical treatment of cervical dumbbell tumors: surgical approach and development of an anatomic classification system. Spine. 2009;34:1307-1314.

39. Ozawa H., Kokubun S., Aizawa T., et al. Spinal dumbbell tumors: an analysis of a series of 118 cases. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;7:587-593.

40. Grillo H.C., Ojemann R.G., Scannell J.G., Zervas N.T. Combined approach to “dumbbell” intrathoracic and intraspinal neurogenic tumors. Ann Thorac Surg. 1983;36:402-407.

41. Payer M., Radovanovic I., Jost G. Resection of thoracic dumbbell neurinomas: single postero-lateral approach or combined posterior and transthoracic approach? J Clin Neurosci. 2006;13:690-693.

42. Takamura Y., Uede T., Igarashi K., et al. Thoracic dumbbell-shaped neurinoma treated by unilateral hemilaminectomy with partial costotransversectomy—case report. Neurol Med-Chir. 1997;37:354-357.

43. Yuksel M., Pamir N., Ozer F., et al. The principles of surgical management in dumbbell tumors. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1996;10:569-573.

44. Konno S., Yabuki S., Kinoshita T., Kikuchi S. Combined laminectomy and thoracoscopic resection of dumbbell-type thoracic cord tumor. Spine. 2001;26:E130-E134.

45. Ng CS, Wong RH, Hsin MK, et al. Recent advances in video-assisted thoracoscopic approach to posterior mediastinal tumours. Surgeon. 8:280–286.

46. Goel A. Posterior inter-body fusion after spinal tumour resection. Br J Neurosurg. 1996;10:201-203.

47. Klekamp J., Samii M. Surgery of spinal nerve sheath tumors with special reference to neurofibromatosis. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:279-289. discussion 289-290

48. Amin A., Saifuddin A., Flanagan A., et al. Radiotherapy-induced malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor of the cauda equina. Spine. 2004;29:E506-E509.

49. Stark A.M., Buhl R., Hugo H.H., Mehdorn H.M. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours—report of 8 cases and review of the literature. Acta Neurochir. 2001;143:357-363. discussion 363-354

50. Ducatman B.S., Scheithauer B.W., Piepgras D.G., et al. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. A clinicopathologic study of 120 cases. Cancer. 1986;57:2006-2021.

51. Farhat H.I., Elhammady M.S., Levi A.D., Aziz-Sultan M.A. Cervical subarachnoid catheter placement for continuous cerebrospinal fluid drainage: a safe and efficacious alternative to the classic lumbar cistern drain. Neurosurgery. 2011;68:52-56. discussion 56

52. Seppala M.T., Haltia M.J., Sankila R.J., et al. Long-term outcome after removal of spinal neurofibroma. J Neurosurg. 1995;82:572-577.