Chapter 185 Management of Degenerative Scoliosis

Terminology

Adult patients presenting with spinal deformity in the absence of previous surgery, trauma, or syndromic or neuromuscular causes are classically placed into one of two categories. The first main category of adult scoliosis involves patients who previously possessed a spinal deformity at a much younger age in the form of infantile, childhood, or adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Such patients become symptomatic during adulthood likely from a progression of these curves with or without superimposed degenerative changes. The second major category of adult scoliosis involves patients without preexisting scoliosis who develop spinal deformity as a result of adult-onset degenerative changes (e.g., disc degeneration, facet joint arthropathy, osteoporosis, and vertebral body compression fractures).1–2 This latter condition is classically referred to as de novo or adult degenerative scoliosis. Differentiating between these two is often determined based on history, symptoms, and imaging.

With regard to history, patients with preexisting curves might acknowledge the presence of their curve since adolescence or young adulthood, which may be corroborated by past photographs. In terms of presenting symptoms, patients with de novo scoliosis typically complain of low back pain, neurogenic claudication, and/or radiculopathy in keeping with most patients with degenerative spine pathology. They might also present with progressive deformity and spinal imbalance leading to severe axial back pain, but such symptoms occur more commonly in patients with preexisting scoliosis. Finally, with regard to imaging, patients with previous idiopathic curves often exhibit larger curves that span more spinal segments, often extending over the thoracic and lumbar regions. These curves may also be associated with significant rotational components. With de novo patients, curves more commonly center on the lumbar region, focally span fewer segments, involve listhesis or focal rotation of one vertebral body over another, and involve degeneration of the lumbosacral junction. Although these generalizations are associated with each type of adult scoliosis, such characteristics are not specific (Table 185-1). For the remainder of the chapter, a general view of de novo scoliosis is discussed.

Table 185-1 Factors that Help Differentiate De Novo or Adult Degenerative Scoliosis from Preexisting Idiopathic Scoliosis Presenting in the Adult

| Factor | De Novo or Adult Degenerative | Previous Idiopathic Curve |

|---|---|---|

| History of previous curve | No | Yes |

| Age | 60s | 40s |

| Sex | Male > female | Female > male |

| Stenosis | Common | Uncommon |

| Curve magnitude | Smaller (15-50 degrees) | Larger (35-80 degrees) |

| Location | Lower lumbar | Thoracolumbar or lumbar |

| Length (in spinal segments) | <5 levels | >5 levels |

| L5-S1 involvement | Yes | No |

| Neurological dysfunction | 50%-90% | 7%-30% |

| Imbalance, coronal | No | Yes |

| Imbalance, sagittal | Yes | No |

Clinical Presentation

In the younger populations with scoliosis, progressive deformity and cosmetic concerns are often the reasons for clinical presentation, but in the adult population, pain is the most common reason for presentation (up to 90%).3–4 This latter group of patients might complain of radicular pain due to neural compression, often on the side of the lumbar concavity. However, complaints of axial pain are common, believed to result from muscle fatigue and spasm over the convexity of the curve.1 Like younger patients with scoliosis, pulmonary compromise occurs only with severe thoracic curves (more than 80 or 90 degrees).1 More commonly though, patients with thoracolumbar deformity with or without kyphosis complain of early satiety with eating because the rib cage can severely indent the abdomen, preventing gastric filling. When evaluating patients, surgeons must try to gain an understanding of the curve’s progression rather than assume the patient is presenting with back pain because degenerative processes have became too debilitating. For instance, a rapidly progressive curve might signify an underlying degenerative neurologic condition (e.g., spinal cord tumor, syrinx). In the absence of this diagnosis, the greatest threat to the patient’s health may be overlooked.

Radiographic Evaluation

Plain Films

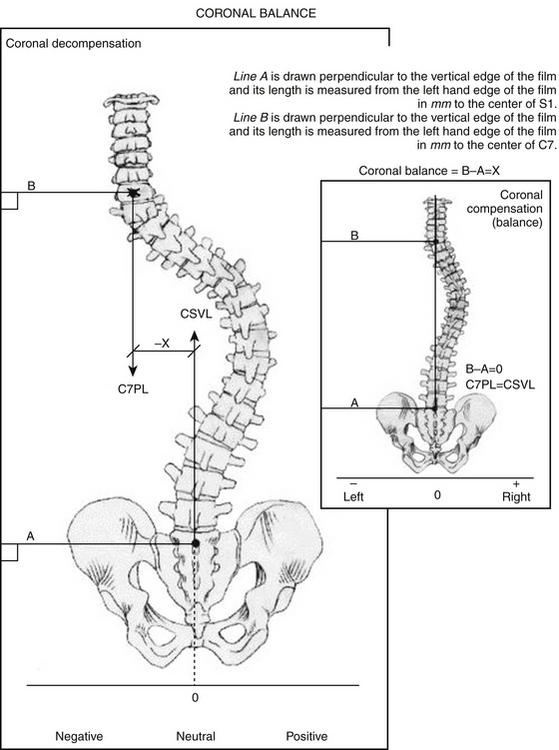

Scoliosis films include three-foot (36-inch) standing posteroanterior (PA) and lateral radiographs at the very minimum. On PA films, Cobb angles are used to measure curves in the coronal plane. First, curves should be measured so as to create the greatest curve angle, and the levels at the top and bottom of such curves should be noted. These curves are used as the foundation to define clinical curve progression. Second, the relationship of the center sacral line to C7 should be documented so as to determine the presence of coronal imbalance or trunk shift (Fig. 185-1). This line bisects a line passing through both iliac crests and ascends perpendicularly. Emami and colleagues have defined coronal imbalance as greater than 25 mm of lateral offset of this plumb line.5 Finally, bending films, traction films, or push-prone films can be used to explore the flexibility of the curves. Such maneuvers can help identify the primary structural curves of the scoliosis, because smaller curves can flatten out on such imaging. In addition, these images might yield information on the flexibility of such curves so that surgeons can quantify the ease or difficulty with which curves may be corrected by surgery.

FIGURE 185-1 Technique for measuring coronal balance.

(From Glassman SD, et al. Correlation of radiographic parameters and clinical symptoms in adult scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 30:6 682-688, 2005.)

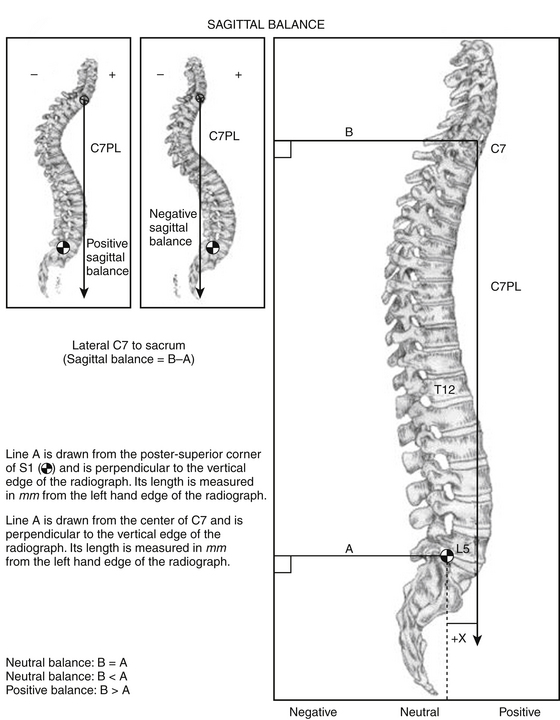

On the lateral films, thoracic kyphosis, lumbar lordosis, and pelvic parameters (especially pelvic incidence) should be measured first. Second, the C7-plumb line and/or T1 tilt should be measured to help determine the patient’s overall sagittal balance (Fig. 185-2). Such measurements are exceedingly important because multiple studies have shown that the quality of life in patients with adult degenerative spinal deformities is highly correlated with sagittal balance, both preoperatively and following spine surgery.6–7 “Normal” sagittal balance is classically defined as a C7 plumb line that passes 2 to 4 cm posterior to the ventral S1 vertebra or 1 cm posterior to the L5–S1 disc space.8–9 An offset of greater than 40 mm has been defined as sagittal imbalance.5 As with the coronal films, bending films can be taken from the lateral view. Such images are often referred to as extension films or supine films, and these can be taken with a bump under the patient’s kyphosis while lying supine. The goal is for the surgeon to estimate how much flexibility there is in the sagittal plane, once again to provide information preoperatively regarding the potential ease or difficulty the surgeon might face in the operating room during deformity-correction maneuvers.

FIGURE 185-2 Technique for measuring sagittal balance.

(From Glassman SD, et al. Correlation of radiographic parameters and clinical symptoms in adult scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 30:6 682-688, 2005.)

Although all the radiographic parameters just outlined can be obtained for all patients with degenerative scoliosis, the imaging of most patients with adult deformity is focused on a lumbar rotational deformity involving a lumbar or thoracolumbar coronal curve that is hypolordotic in the sagittal plane. Such deformity is often associated with a relatively flexible thoracic compensatory curve typically less than 30 degrees.1 In addition, rotatory subluxation or lateral translation at L3–4 and obliquity at L4–5 are the most commonly affected areas.1 Although not necessarily obvious on plain films, it must be noted that many patients with long-standing deformities in the sagittal plane develop hip and knee flexion contractures. Such problems can limit the patient from obtaining a balanced posture (head over pelvis and over feet) even following an apparent surgical correction of spinal imbalance. In these patients, further evaluation of hip pathology may be required prior to attempting spine surgery.

Bone Quality

Because of the high prevalence of osteoporosis in patients older than 50 years, poor bone quality can affect the surgical approach and instrumentation options.10 Although plain radiographs and computed tomography (CT) imaging can help predict bone quality, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) is the gold standard for diagnosing osteoporosis. The T-score compares the patient’s bone density to the optimal peak bone density for gender, and it is reported as the number of standard deviations below the average. A T-score greater than −1.0 is considered normal. A T-score less than −1.0 is considered osteopenia and the patient is considered at risk for developing osteoporosis. A T-score of less than −2.5 is diagnostic of osteoporosis. The Z-score is used to compare results to other patients of the same age, weight, ethnicity, and gender. It is useful to determine if there is something unusual contributing to bone loss. A Z-score of less than −1.5 raises concern that factors other than aging are contributing to osteoporosis, including thyroid dysfunction, malnutrition, tobacco use, and medication interactions. Some surgeons suggest performing this study on all women older than 50 years and all men older than 60 years who are considering surgery. However, in addition to age, risk factors for osteoporosis include history of fracture as an adult or fracture in a first-degree relative, white or Asian ethnicity, smoking, low body weight, female sex, dementia, and poor health.1,11

Classification Systems

The vast majority of study dedicated to patients with scoliosis since the 1980s has been focused on the adolescent form. Although such systems can apply to older patients who become symptomatic from preexisting adolescent idopathic curves, they are not appropriate for the classic de novo degenerative curves. Currently, three classification systems exist for adult scoliosis: the Aebi system,12 the Schwab system,7 and the Scoliosis Research Society (SRS) system.13

The Schwab classification was created following the outcomes of a multicenter, prospective, clinical series of adult patients with deformity. When correlated with clinical outcome measurements, specifically the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) and SRS outcome measure, three parameters were useful for classifying patients: deformity apex, lordosis, and intervertebral subluxation. In this classification scheme, patients are first grouped by apical level and assigned a specific type from I to V. A lumbar lordosis modifier based on severity is added with types A to C. Finally, a subluxation modifier based on severity is added with types 0, +, and ++. The strength of this classification scheme is that it assigns higher grades to patients with radiographic parameters associated with increased surgical rates, disability, and pain. However, a potential weakness of this system is that it is not thoroughly anatomically descriptive but rather focuses on clinical impact factors.

The SRS classification was created based fundamentally on radiographic curve type followed by the addition of three modifiers. First, the coronal curve is grouped into one of six major types based on apex location. A regional sagittal modifer exists to underscore the role that hypolordosis or kyphosis plays in relation to health status and surgical strategies in the four major regions of the spine.14 A lumbar degenerative modifier is then used to help quantify the degree of lumbar degenerative disease including loss of disc height, facet arthropathy, rotatory subluxation, listhesis, and the junctional L5–S1 curve. Finally, a global balance modifier is included to assess the overall sagittal or coronal balance via the C7 plumb line. Although this classification system may be more anatomically specific than the previously mentioned two classification schemes and has been shown to have good interobserver reliability, it generally is used as a research tool owing to its cumbersome nature.

Management

Conservative Management

The approach to patients who have adult degenerative scoliosis and present with axial pain with or without neural compression symptoms should involve the same conservative treatment as would be prescribed for similar adult patients who possess degenerative spine changes without deformity. Physical therapy, activity modification, traction, aquatic therapy, and oral medications (e.g., antiinflammatory medication, muscle relaxants, analgesics) are initially used. Second-tier treatments may include epidural steroid injections, facet injections, and selective nerve root blocks. Although the stabilizing effects of bracing can help relieve back pain, it has not been shown to prevent curve progression,15 and it may be associated with deconditioning and muscle atrophy if worn for protracted periods.

During conservative treatment, it is also essential to honestly and accurately convey the surgical risk associated with such procedures. Beyond mere operative risk, patients might possess multiple risk factors that can negatively affect their success following surgery. For instance, it has been well documented that certain conditions are associated with poor clinical outcomes,1 including tobacco use,16 coronary or cerebrovascular disease,17 chronic pulmonary disease or asthma, diabetes,18 osteoporosis, nutritional deficiency,19 depression,20 and active life stressors.21

Surgery

As with patients who suffer from degenerative conditions of the spine without deformity, surgery should be offered only after conservative management has failed. Controversy exists regarding the need to reduce the deformity in such patients as opposed to merely treating painful neural compression with directed decompression or fusing vertebrae in situ for degenerative instability. However, in patients with curves at risk for progression (more than 50 to 60 degrees for thoracic curves or more than 40 degrees for lumbar curves), surgical correction should be considered.1 Korovessis and colleagues analyzed risk factors for lumbar curves and found that risk factors for progression included curves greater than 30 degrees, rotation of the apical vertebra of greater than 33%, lateral listhesis greater than 6 mm, and poor seating of the L5 vertebra over the S1 vertebra.22 Even more important, however, should be thorough assessment of preoperative sagittal balance. For this reason, many deformity spine surgeons suggest standing films for any patient being considered for a fusion involving thoracic or lumbar levels. Generally speaking, thoracic kyphosis greater than 60 degrees and the presence of any lumbar kyphosis (greater than 5 degrees) should be considered for surgical correction.1

Spinal Balance

As stated previously, sagittal balance has been shown to be one of the most important factors associated with patient outcome following adult deformity surgery.1,6–7,23 Although coronal balance is not nearly as important in such patients, proper balance in all planes provides an ergonomic posture, placing the head over the pelvis and over the feet. Without such balance, patients expend greater energy trying to obtain balance, which leads to muscle fatigue, strain, and pain. In addition, such imbalance can place excessive stresses on both instrumented spine segments as well as on normal, non-instrumented segments. As a result, such imbalance can lead to additional degeneration, instrumentation failure, and progressive imbalance.1

Proximal and Distal Fusion Segments

In general, instrumentation should not terminate at or near the apical vertebra in the sagittal or coronal plane. In the sagittal plane, the apical vertebra is the vertebra at the apex of the thoracic kyphosis. In the coronal plane, the apical vertebra is at the apex of the largest coronal curve. In addition, instrumentation should extend to a neutral vertebra to balance the fixation construct within the deformity.1 The neutral vertebra is the vertebra associated with little or no angulation or rotation at the rostral and caudal disc spaces of the curve. Many surgeons also suggest that the distal segment of a fusion should not end at the thoracolumbar junction (T11 or T12).24

Patients in this population have significant disc degeneration in both degree and vastness across multiple segments of the spine. It has been shown that stopping a fusion adjacent to a severely degenerated disc, especially with subluxation or fixed obliquity, can result in poor outcomes. Therefore, when developing the construct, forethought must be given to not stopping at a severely degenerated disc. In addition, given the prevalence of degenerative changes at the L5–S1 junction, L5–S1 spondylolithesis, previous laminectomy at L5–S1, or an L5–S1 obliquity (more than 15 degrees), patients with adult scoliosis often require instrumentation to the sacrum.1 Unfortunately, such fixation places enormous stresses on both the lumbosacral junction and the S1 pedicle screws, traditionally leading to a high failure rate of lone posterior constructs ending at S1.25–26 Compounding such stress concentration is that fact that the S1 pedicles are the largest pedicles in the spine and thus the ratio of weaker cancellous bone to stronger cortical bone is decreased. For this reason, pedicle screw purchase is weaker compared to other spinal segments. In addition, fusions to the sacrum in adult degenerative scoliosis patients have been found to require more surgical procedures and have had more postoperative complications than those ending at L5.26 Kim and colleagues noted a 24% rate of pseudarthrosis for fusions extending to the sacrum.27

For such reasons, some surgeons suggest that fusions to the sacrum should be avoided when possible.28 However, fusions ending at L5 have been associated with a 61% rate of adjacent segment disease and resultant negative impact on sagittal balance.29 As a result, most deformity surgeons recommend that long posterior pedicle screw constructs should extend to the sacrum if deemed necessary but should involve a combination or all of the following to improve biomechanical stability at the lumbosacral junction: bicortical S1 pedicle screws, L5–S1 interbody support, additional sacral screws (S1 alar screws, S2 screws), and/or iliac screws.30–31

Correction of Deformity

Sagittal Deformity

Posterior osteotomies involve resecting the posterior elements of the spine, namely the medial facet joints and the distal pars interarticularis, followed by posterior compression, which allows posterior shortening and increases lordosis. Originally described by Ponte, the procedure involving bilateral facetectomies with removal of the ligamentum flavum has been termed the Ponte osteotomy.32 Smith-Peterson and colleagues described a similar technique for ankylosis spondylitis patients who possess arthrodesis of the posterior osteoligamentous complex.33 Often considered to be a synonymous procedure by surgeons, this technique has become known as the Smith-Peterson osteotomy. Both types are referred to as “chevron” osteotomies, because of the shape of the bone removed, or as “extension” osteotomies because they can increase segmental lordosis.34

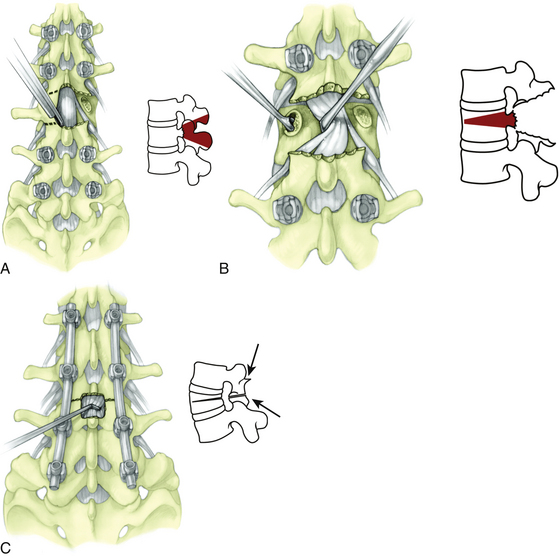

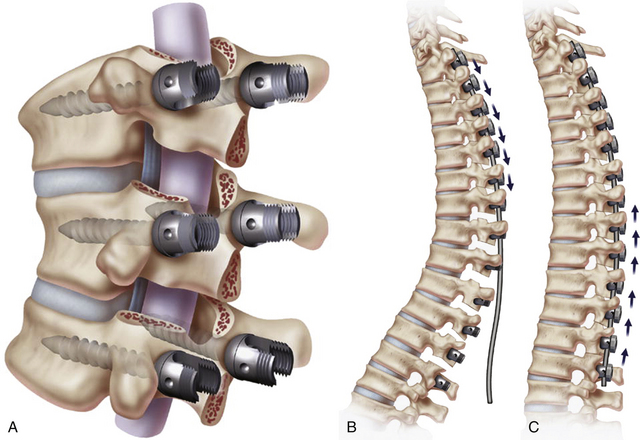

The Ponte osteotomy and Smith-Peterson osteotomy are performed by first removing the facet joints on both sides of the spinal level of interest, including the superior articulating facet of the lower vertebra and the inferior articulating facet of the upper vertebra. The inferior portion of the rostral laminae and spinous process of the upper vertebra are also removed, followed by resection of the ligamentum flavum. The lower laminae are then decorticated for arthrodesis, and the osteotomy gap is compressed and held in compression with posterior instrumentation (Fig. 185-3).35 Because these procedures rely on an axis of rotation at the posterior aspect of the disc space, the anterior portion of the disc must be widened commensurately to achieve correction. Therefore, a mobile disc is required for this maneuver to be successful. If the disc is not mobile, the disc and annulus must be “released” via interbody work. In general, the amount of correction achieved with such osteotomies is roughly 5 to 10 degrees per level.36 In patients with kyphosis that is nonfocal and spans multiple segments, multiple Smith-Peterson osteotomies can adequately reduce the curve. In addition, placement of an interbody graft or spacer in the middle or anterior third of the disc space provides greater lordosis (up to 15 degrees per level) and can augment fusion.35

FIGURE 185-3 A, Ponte osteotomy with instrumentation in place. B, Before correction. C, After posterior compression.

(From Geck MJ, et al. The Ponte procedure: posterior only treatment of Scheuermann’s kyphosis using segmental posterior shortening and pedicle screw instrumentation. J Spinal Disord Tech 20:8 586-593, 2007.)

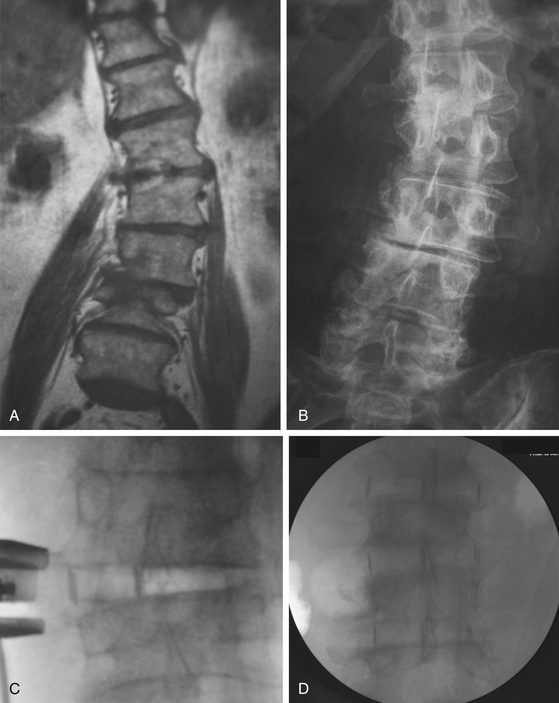

Originally described by Thomasen in 1985, the pedicle subtraction osteotomy has been used to obtain a greater degree of lordosis at an individual segment.37 Such osteotomies have been associated with more than 30 degrees of sagittal correction at a single level. However, they are often associated with greater blood loss, significant intraoperative spinal instability, and a higher rate of postoperative neurologic morbidity. During this procedure, pedicle screw fixation at the adjacent levels is done early in the procedure to provide temporary stabilization during the osteotomy procedure. Laminectomies and bilateral facetectomies are then performed at the index level. The pedicles are removed bilaterally with an osteotome or drill. The vertebral body is decancellated in a wedge-shaped fashion, so that the wider resection is posterior and the focal point of the wedge is anterior. This maneuver is often done with one temporary rod on the contralateral side of the bony resection; the rod is then switched to the ipsilateral side to accomplish a bilateral osteotomy. Care must be taken to completely separate the dura and nerve roots from local epidural tethers, especially if scar is present from a previous surgery. Using temporary rods for control and constant neurophysiologic monitoring, the wedge is closed so that the edges of the osteotomy appose. Larger contoured rods then allow final fixation (Fig. 185-4).

Although pedicle subtraction osteotomy has been considered a robust form of sagittal plane correction, it is most often used in the lumbar spine for multiple reasons. First, the majority of the degenerative pathology in adult patients is in this region. Second, patients often lose sagittal balance in the lumbar and lumbosacral areas. Finally, many patients have undergone previous fusions with loss of lordosis, leading to flat-back deformity, which must be addressed focally. However, pedicle subtraction osteotomy might not provide the same amount of correction in the thoracic spine due to the shorter height of the thoracic vertebra. As a result, when large focal deformity corrections are required in the thoracic spine, a vertebral column resection may be used.

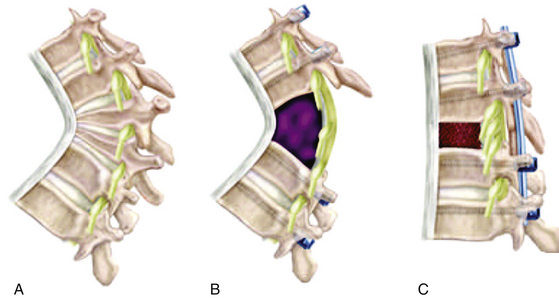

Like the pedicle subtraction osteotomy, the vertebral column resection is a severely destabilizing maneuver. Similar to a vertebrectomy for tumor or trauma, the vertebral column resection is done from a posterior route in much the same way as a pedicle subtraction osteotomy. However, rather than create a wedge-shaped osteotomy, the entire vertebra and adjacent endplates are removed. Deformity correction then may proceed by compressing the remaining vertebral bodies together in a controlled fashion with temporary rods or after an interbody graft or strut is placed anteriorly. In the thoracic spine, nerve roots can be sacrificed without morbidity, thus allowing better access laterally and anteriorly. However, cord manipulation must be avoided because such reduction maneuvers are associated with a small but significant risk for spinal cord damage. Because lumbar roots cannot be sacrificed without causing neurologic morbidity, pedicle subtraction osteotomy is generally used for large focal sagittal correction in the lumbar spine, and vertebral column resection is used for focal sagittal correction in the thoracic spine (Fig. 185-5).

Interbody work is another means by which sagittal balance can be improved. Discectomy can be accomplished posteriorly via posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF) and transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF) approaches or from anterior interbody lumbar fusion (ALIF) approaches, the last of which involves retroperitoneal or transperitoneal access. More recently, minimally invasive techniques have been used to allow more aggressive discectomy and annulotomy maneuvers. A greater “release” is obtained with aggressive annulotomy and osteophyte removal compared to the traditional PLIF and TLIF approaches, yet the access-related morbidity of the ALIF procedures may be avoided. Such lateral approaches have been named extreme lateral interbody fusion (XLIF) and direct lateral interbody fusion (DLIF) approaches. Early evidence suggests that large lordotic grafts can be placed at multiple levels, similar to an ALIF, without the need for an extensive anterior approach (Fig. 185-6).

Coronal Deformity

Correction of coronal deformity does not receive as much attention as sagittal restoration in adult patients because patients can tolerate coronal imbalance to a higher degree. However, in patients with large curves, symptomatic coronal imbalance, shoulder asymmetry, or pelvic obliquity, coronal correction can significantly help the patient. The adult spine does not reduce easily to a contoured rod because of its inherent stiffness and poor bone quality. As a result, coronal deformity is approached using the same techniques discussed earlier to obtain sagittal balance. Although such releases of the osteoligamentous complexes and intervertebral discs can, on their own, restore the spine to a coronally straight alignment, modification of such techniques may be required. For instance, quadrangular pedicle subtraction osteotomy can be used with one side more aggressively osteotomized than the other, allowing restoration of the Cobb angle. In addition, interbody grafts can be placed eccentrically. When combined with asymmetric pedicle screw compression, coronal balance can be drastically restored.

Outcomes

The results of operative correction for adult spinal deformity have improved significantly since the turn of the 21st century. The goals of deformity surgery are different in adult patients compared to adolescent ones. In adult patients, the goals are to arrest curve progression, provide pain relief, and improve function. Therefore, surgery should be used to create a stable, balanced spine rather than to achieve dramatic and complete curve correction.24 Interestingly, Takahashi and colleagues compared patients older than 50 years with younger adult patients and found that radiographic results were less satisfactory in the older cohort, but pain relief was more reliably obtained compared to the younger cohort.38 Not surprisingly however, as with most adult patients with low back pathology, pain is seldom totally alleviated with surgery. Nonetheless, the incidence of residual pain after complex spinal reconstructive surgery has been shown to vary between 5% and 15%.8 In addition, if coronal and sagittal balance are achieved and maintained with a solid fusion, the outcomes can be very promising.

Hu et al. retrospectively evaluated the outcomes of patients older than 40 years who underwent major spinal reconstructive surgery and found more than 81% patient satisfaction and significant improvements in many areas of functional status.39 Dickson and colleagues compared the outcomes of 81 adult patients undergoing operative treatment for idiopathic scoliosis with 30 patients who declined operative management.40 At an average of 5 years of follow-up, they found that treated patients reported a significantly greater decrease in pain and fatigue with improvement in self-image and functionality as compared to the nontreated group. Albert and colleagues have also shown statistically significant improvements in functional outcome, pain, and body image in adults following spinal reconstructive surgery.41

Complications

As with any group of surgical procedures, complications associated with the surgical correction of adult deformity depends on a host of factors linked to the patient, pathology, and operative goals. For instance, McDonnell and colleagues showed that the complication rate for spinal surgical procedures in general can increase up to 500% when the youngest patients are compared to the oldest patients.1,42 Such an increase has clearly been shown with regard to surgical site infections. Scudaro and colleagues showed that although scoliosis patients of all types can have a small rate of surgical site infections between 1% and 2%, this rate increased to close to 5% when the outcomes of adult patients were reviewed.43 Neurologic complications can be severe, especially for patients with severe deformity reductions around the thoracic spinal cord. Bridwell and colleagues have shown such complications can occur in up to 5%,44 and risk factors can include combined anterior and posterior surgery, severe rigid curves, and hyperkyphosis.8 In addition, postoperative vision loss can be devastating and has been associated with low back surgery in the prone position in which large volume resuscitation is required.

Due to both the extensive surgery required and more medically fragile patients, the overall complication rate for adult deformity patients has been estimated to be at least 33%.5,38 Regardless of the seemingly small risk of severe complications such as neurologic deficit, myocardial infarction, or death for such patients, most experienced adult deformity surgeons explain to their patients that complications are extremely common. Mortality remains low, but not insignificant, at less than 1%.8 However, given the advanced age, osteoporosis, and malnutrition common to this group, combined with the aggressive surgical maneuvers required, the chances of developing early complications (less than 1 month postoperatively) such as cerebrospinal fluid leak, pneumonia, ileus, urinary tract infections, and deep vein thrombi can be quite high (greater than 50%). Late complications (later than 1 month postoperatively) are also common and include implant failure, junctional kyphosis (2% of adult deformity patients),5,29 adjacent segment deterioration (up to 10% at L5–S1),29 and pseudarthrosis or nonunion (5% to 27% in adult deformity surgery).8,29 Although such surgeries are routinely done with good success, patients are often not told that they are likely to have some complication during the recovery process.

Aebi M. The adult scoliosis. Eur Spine J. 2005;14:925-948.

Albert T.J., Mesa J.J., Eng K., et al. Health outcome assessment before and after adult deformity surgery. A prospective study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20:2002-2004.

Birknes J.K., White A.P., Albert T.J., et al. Adult degenerative scoliosis: a review. Neurosurgery. 2008;63(suppl 3):94-103.

Bradford D.S., Tay B.K., Hu S.S. Adult scoliosis: surgical indications, operative management, complications, and outcomes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 24, 1999. 22617-2529

Bridwell K.H. Decision making regarding Smith-Petersen vs. pedicle subtraction osteotomy vs. vertebral column resection for spinal deformity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(suppl 19):S171-S178.

Bridwell K.H., Lenke L.G., Baldus C., Blanke K., et al. Major intraoperative neurologic deficits in pediatric and adult spinal deformity patients. Incidence and etiology at one institution. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998;23:324-331.

Bridwell K.H., Lewis S.J., Rinella A., et al. Pedicle subtraction osteotomy for the treatment of fixed sagittal imbalance. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(suppl 1):44-50.

Eck K.R., Bridwell K.H., Ungacta F.F., et al. Complications and results of long adult deformity fusions down to l4, l5, and the sacrum. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26:E182-E192.

Geck M.J., Macagno A., Ponte A., Shufflebarger H.L., et al. The Ponte procedure: posterior only treatment of Scheuermann’s kyphosis using segmental posterior shortening and pedicle screw instrumentation. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2007;20:586-593.

Glassman S.D., Berven S., Bridwell K., et al. Correlation of radiographic parameters and clinical symptoms in adult scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:682-688.

Hu S.S., Holly E.A., Lele C., et al. Patient outcomes after spinal reconstructive surgery in patients ≥40 years of age. J Spinal Disord. 1996;9:460-469.

Kim Y.J., Bridwell K.H., Lenke L.G., et al. An analysis of sagittal spinal alignment following long adult lumbar instrumentation and fusion to L5 or S1: can we predict ideal lumbar lordosis? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31:2343-2352.

Klein J.D., Hey L.A., Yu C.S., et al. Perioperative nutrition and postoperative complications in patients undergoing spinal surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21:2676-2682.

Korovessis P., Piperos G., Sidiropoulos P., Dimas A., et al. Adult idiopathic lumbar scoliosis. A formula for prediction of progression and review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19:1926-1932.

Kostuik J.P., Israel J., Hall J.E. Scoliosis surgery in adults. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1973;93:225-234.

Lowe T., Berven S.H., Schwab F.J., Bridwell K.H. The SRS classification for adult spinal deformity: building on the King/Moe and Lenke classification systems. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(suppl 19):S119-S125.

McDonnell M.F., Glassman S.D., Dimar J.R.2nd, et al. Perioperative complications of anterior procedures on the spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:839-847.

Polly D.W.Jr., Klemme W.R., Cunningham B.W., et al. The biomechanical significance of anterior column support in a simulated single-level spinal fusion. J Spinal Disord. 2000;13:58-62.

Schwab F., Farcy J.P., Bridwell K., et al. A clinical impact classification of scoliosis in the adult. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31:2109-2114.

Schwab F.J., Smith V.A., Biserni M., et al. Adult scoliosis: a quantitative radiographic and clinical analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27:387-392.

Smith J.S., Shaffrey C.I., Kuntz C .4th., Mummaneni P.V., et al. Classification systems for adolescent and adult scoliosis. Neurosurgery. 2008;63(suppl 3):16-24.

Smith-Petersen M.N., Larson C.B., Aufranc O.E. Osteotomy of the spine for correction of flexion deformity in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1969;66:6-9.

Takahashi S., Delecrin J., Passuti N. Surgical treatment of idiopathic scoliosis in adults: an age-related analysis of outcome. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27:1742-1748.

van Dam B.E. Nonoperative treatment of adult scoliosis. Orthop Clin North Am. 1988;19:347-351.

Winter R.B., Lonstein J.E., Denis F. Pain patterns in adult scoliosis. Orthop Clin North Am. 1988;19:339-345.

1. Birknes J.K., White A.P., Albert T.J., et al. Adult degenerative scoliosis: a review. Neurosurgery. 2008;63(suppl 3):94-103.

2. Herkowitz H.N., Kurz L.T. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis. A prospective study comparing decompression with decompression and intertransverse process arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:802-808.

3. Kostuik J.P., Israel J., Hall J.E. Scoliosis surgery in adults. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1973;93:225-234.

4. Winter R.B., Lonstein J.E., Denis F. Pain patterns in adult scoliosis. Orthop Clin North Am. 1988;19:339-345.

5. Emami A., Deviren V., Berven S., et al. Outcome and complications of long fusions to the sacrum in adult spine deformity: luque-galveston, combined iliac and sacral screws, and sacral fixation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27:776-786.

6. Glassman S.D., Berven S., Bridwell K., et al. Correlation of radiographic parameters and clinical symptoms in adult scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:682-688.

7. Schwab F., Farcy J.P., Bridwell K., et al. A clinical impact classification of scoliosis in the adult. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31:2109-2114.

8. Bradford D.S., Tay B.K., Hu S.S. Adult scoliosis: surgical indications, operative management, complications, and outcomes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 24, 1999. 2617-2629

9. McLain R.F., Ferrara L., Kabins M. Pedicle morphometry in the upper thoracic spine: limits to safe screw placement in older patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27:2467-2471.

10. Lane J.M., Riley E.H., Wirganowicz P.Z. Osteoporosis: diagnosis and treatment. Instr Course Lect. 1997;46:445-458.

11. Heinemann D.F. Osteoporosis. An overview of the National Osteoporosis Foundation clinical practice guide. Geriatrics. 2000;55:31-36.

12. Aebi M. The adult scoliosis. Eur Spine J. 2005;14:925-948.

13. Lowe T., Berven S.H., Schwab F.J., Bridwell K.H., et al. The SRS classification for adult spinal deformity: building on the King/Moe and Lenke classification systems. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(suppl 19):S119-S125.

14. Smith J.S., Shaffrey C.I., Kuntz C.4th, Mummaneni P.V., et al. Classification systems for adolescent and adult scoliosis. Neurosurgery. 2008;63(suppl 3):16-24.

15. van Dam B.E. Nonoperative treatment of adult scoliosis. Orthop Clin North Am. 1988;19:347-351.

16. Warner M.A., Offord K.P., Warner M.E., et al. Role of preoperative cessation of smoking and other factors in postoperative pulmonary complications: a blinded prospective study of coronary artery bypass patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 1989;64:609-616.

17. Auerbach A.D., Goldman L. β-Blockers and reduction of cardiac events in noncardiac surgery: clinical applications. JAMA. 2002;287:1445-1447.

18. Moitra V.K., Meiler S.E. The diabetic surgical patient. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2006;19:339-345.

19. Klein J.D., Hey L.A., Yu C.S., et al. Perioperative nutrition and postoperative complications in patients undergoing spinal surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21:2676-2682. 22

20. Rosenberger P., Jokl H., Ickovics J. Psychosocial factors and surgical outcomes: an evidence-based literature review. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14:397-405.

21. Clarke D.M., Russell P.A., Polglase A.L., McKenzie D.P., et al. Psychiatric disturbance and acute stress responses in surgical patients. Aust N Z J Surg. 1997;67:115-118.

22. Korovessis P., Piperos G., Sidiropoulos P., Dimas A., et al. Adult idiopathic lumbar scoliosis. A formula for prediction of progression and review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19:1926-1932.

23. Schwab F.J., Smith, V.A., Biserni M., et al. Adult scoliosis: a quantitative radiographic and clinical analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27:387-392.

24. Heary R.F., Kumar S., Bono C.M. Decision making in adult deformity. Neurosurgery. 2008;63(suppl 3):69-77.

25. Eck K.R., Bridwell K.H., Ungacta F.F., et al. Complications and results of long adult deformity fusions down to l4, l5, and the sacrum. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26:E182-E192.

26. Kostuik J., Hall B.B. Spinal fusions to the sacrum in adults with scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1983;8:489-500.

27. Kim Y.J., Bridwell K.H., Lenke L.G., et al. An analysis of sagittal spinal alignment following long adult lumbar instrumentation and fusion to L5 or S1: can we predict ideal lumbar lordosis? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31:2343-2352.

28. Bridwell K.H., Edwards C.C.2nd, Lenke L.G. The pros and cons to saving the L5–S1 motion segment in a long scoliosis fusion construct. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28:S234-S242.

29. Edwards C.C.2nd, Bridwell K.H., Patel A., et al. Thoracolumbar deformity arthrodesis to L5 in adults: the fate of the L5–S1 disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28:2122-2131.

30. Kuklo T.R., Bridwell K.H., Lewis S.J., et al. Minimum 2-year analysis of sacropelvic fixation and L5–S1 fusion using S1 and iliac screws. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26:1976-1983.

31. Polly D.W.Jr., Klemme W.R., Cunningham B.W., et al. The biomechanical significance of anterior column support in a simulated single-level spinal fusion. J Spinal Disord. 2000;13:58-62.

32. Geck M.J., Macagno A., Ponte A., Shufflebarger H.L., et al. The Ponte procedure: posterior only treatment of Scheuermann’s kyphosis using segmental posterior shortening and pedicle screw instrumentation. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2007;20:586-593.

33. Smith-Petersen M.N., Larson C.B., Aufranc O.E. Osteotomy of the spine for correction of flexion deformity in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1969;66:6-9.

34. Bridwell K.H. Decision making regarding Smith-Petersen vs. pedicle subtraction osteotomy vs. vertebral column resection for spinal deformity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(suppl 19):S171-S178.

35. La Marca F., Brumblay H. Smith-Petersen osteotomy in thoracolumbar deformity surgery. Neurosurgery. 2008;63(suppl 3):163-170.

36. Cho K.J., Bridwell K.H., Lenke L.G., et al. Comparison of Smith-Petersen versus pedicle subtraction osteotomy for the correction of fixed sagittal imbalance. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:2030-2037. discussion 2038

37. Thomasen E.. Vertebral osteotomy for correction of kyphosis in ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1985;194:142-152

38. Takahashi S., Delecrin J., Passuti N. Surgical treatment of idiopathic scoliosis in adults: an age-related analysis of outcome. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27:1742-1748.

39. Hu S.S., Holly E.A., Lele C., et al. Patient outcomes after spinal reconstructive surgery in patients ≥40 years of age. J Spinal Disord. 1996;9:460-469. 6

40. Dickson J.H., Mirkovic S., Noble P.C., et al. Results of operative treatment of idiopathic scoliosis in adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:513-523.

41. Albert T.J., Purtill J., Mesa J., et al. Health outcome assessment before and after adult deformity surgery. A prospective study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20:2002-2004.

42. McDonnell M.F., Glassman S.D., Dimar J.R.II, et al. Perioperative complications of anterior procedures on the spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:839-847.

43. Weiss L.E., Vaccaro A.R., Scuderi G., et al. Pseudarthrosis after postoperative wound infection in the lumbar spine. J Spinal Disord. 1997;10:482-487.

44. Bridwell K.H., Lenke L.G., Baldus C., Blanke K., et al. Major intraoperative neurologic deficits in pediatric and adult spinal deformity patients. Incidence and etiology at one institution. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998;23:324-331.

45. Bridwell K.H., Lewis S.J., Rinella A., et al. Pedicle subtraction osteotomy for the treatment of fixed sagittal imbalance. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(suppl 1):44-50.