Management of cerebral aneurysms

Aneurysm rupture

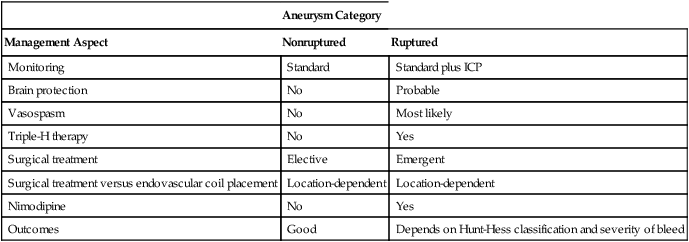

Nimodipine is the standard drug used to manage vasospasm because it improves collateral blood flow (Table 134-1); however, it does not relieve the vasospasm of the main vessel. Optimal management entails the use of hypertension, hydration, and hemodilution (triple-H therapy) to overcome the vasospasm, which usually lasts for up to 14 days.

Table 134-1

| Aneurysm Category | ||

| Management Aspect | Nonruptured | Ruptured |

| Monitoring | Standard | Standard plus ICP |

| Brain protection | No | Probable |

| Vasospasm | No | Most likely |

| Triple-H therapy | No | Yes |

| Surgical treatment | Elective | Emergent |

| Surgical treatment versus endovascular coil placement | Location-dependent | Location-dependent |

| Nimodipine | No | Yes |

| Outcomes | Good | Depends on Hunt-Hess classification and severity of bleed |

ICP, Intracranial pressure; triple-H therapy, use of hypertension, hydration, and hemodilution.

Anesthetic management

Aside from avoiding hyperglycemia and fever during periods when the brain is at risk for developing ischemic injury, definitive evidence for brain-protective interventions are devoid in the human literature (see Chapter 131). Despite this, many physicians use barbiturates or propofol to achieve burst suppression (4-6 bursts/min) during critical periods of aneurysm operations. The Intraoperative Hypothermia for Aneurysm Surgery Trial did not show any benefit of a mild temperature decrease (to 33° C) during operations. No other research results have been published on this topic recently.