Chapter 189 Management of Cauda Equina Tumors

Most of these tumors are benign, which justifies an aggressive surgical approach, using magnification techniques and microsurgical instrumentation. Adjuvant therapy is unnecessary, at least after the first procedure. In 1996 we performed a retrospective review of the French cases with 231 patients.1,2 Our personal series comprises 31 patients. It is not always easy to make a distinction between a true CET and a tumor arising from the neighboring structures, even with the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data, and it is sometimes necessary to obtain the operative and anatomopathologic findings to correctly classify the tumor. In the literature, many isolated cases are reported, but large series and practical advice for management are seldom encountered.

Definition of Cauda Equina Tumors

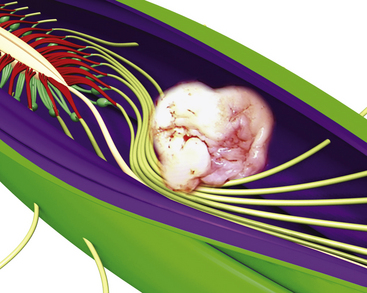

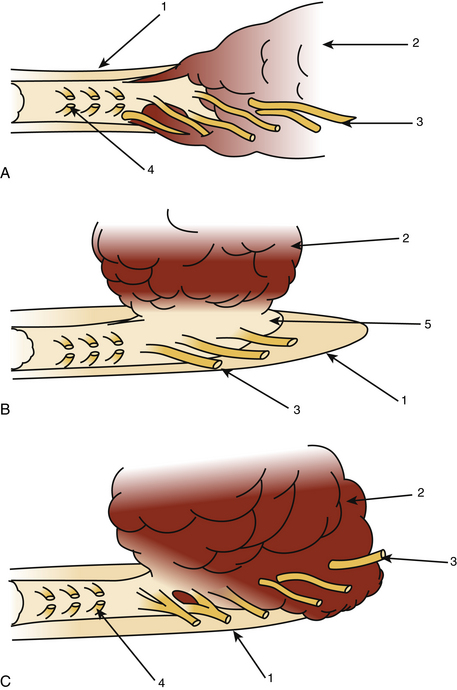

Primary tumors of the cauda equina arise from the different intrinsic structures of the region, such as the filum, the nerve sheaths, intrinsic vessels of the nerves, conjunctive tissue, and embryologic remnants.3 Some authors include tumors sprouting from the surrounding tissues—meningeal envelopes, epidural structures, and bone—but this does not seem to be the proper nosologic approach in description of this pathology, even if their clinical features present some similarities. It is in fact relatively difficult to classify metastatic tumors that, although not infrequent, do not constitute a surgical problem (Fig. 189-1).

Clinical Presentation

The involved population includes both sexes, with a slight male predominance, which is more marked for ependymomas (nearly 61%).1,2 Mean age for all CETs is 47 years, but there is a strong correlation between age and tumor type: 34.6 years ± 16 years for ependymomas and 51 years ± 17 years for benign neurinomas.

The time interval between the first symptom and the diagnosis ranges from 1 month to 264 months. In our series the mean delay was about 34 months for 50% of the patients. There is no influence of age but rather a strong correlation with tumor type: long-lasting time lapse, 50 months for neurofibromas and paragangliomas; medium, 20 months for neurinomas and ependymomas; short for malignant tumors, especially metastasis. In a few cases intratumoral bleeding caused by a trauma results in an acute cauda equina syndrome.4

Diagnostic Evaluation

Electromyography and evoked potentials are of limited value in the investigation of CETs.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

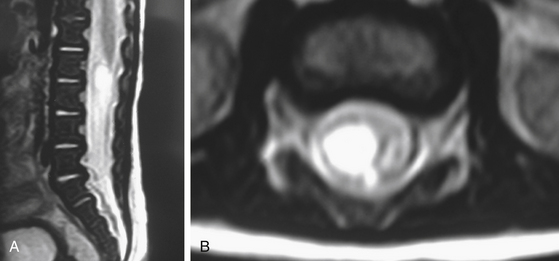

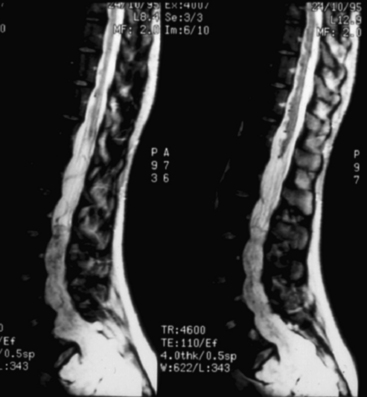

MRI is the gold standard for diagnosis. It must include T1- and T2-weighted sequences, without and with gadolinium administration, and in sagittal and axial views. It demonstrates the existence and the size of the tumor, cystic components, intratumor bleeding, vascularity, and the relation of the tumor to the conus, and it is contributive in 100% of cases. It also rules out other pathologies. It leads to a presumptive histopathologic diagnosis.5

Management Decisions

The functional problems and prognosis have to be precisely described to the patient and his or her family, and the expectations must be realistic. Patients harboring minor neurologic impairment must be aware that neurologic deterioration can result from the operation, and in all cases hospitalization in a rehabilitation center will probably be necessary. The sphincter dysfunction is the least likely symptom to improve after surgery if it has existed for several weeks, and it may be amplified or appear postoperatively. As in intramedullary spinal tumors, the final outcome depends on the preoperative neurologic status of the patient. Because those tumors are nearly always benign, there is no alternative treatment to surgery. The goals of the operation are tumor removal and preservation or improvement of neurologic function.

Technical Adjuncts to Tumor Removal

Intraoperative stimulation of motor roots may be used for their identification when they are surrounded by tumor tissue.6 Evoked potential recordings are sometimes used, but they also are far less effective than in spinal cord tumors, and there is no evidence that they improve outcome.

Surgical Technique

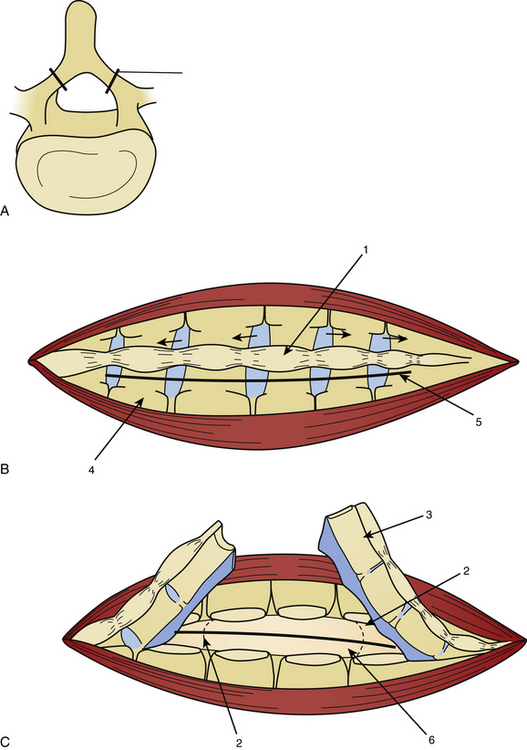

Laminotomy must be performed systematically in infants and young adults, with reconstruction of a normal anatomy by reinserting the posterior processes prevents growth deformation in the young but also decreases the post-operative pain and the frequency of CSF leaks (Fig. 189-2).

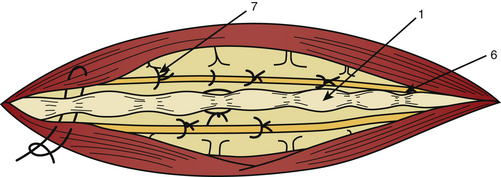

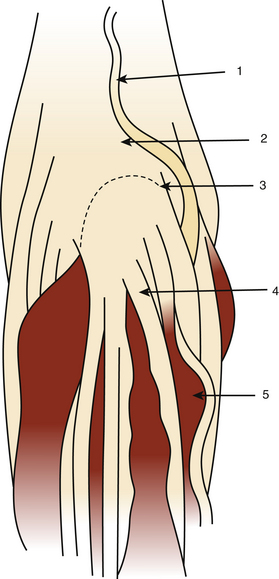

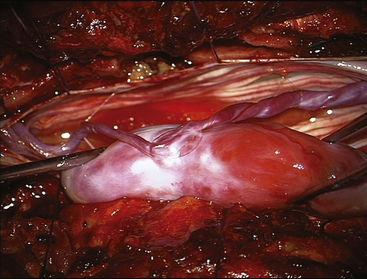

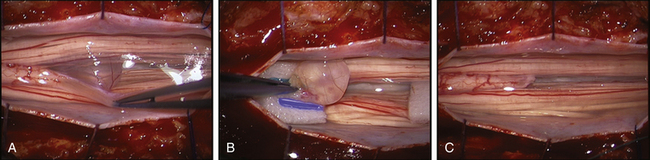

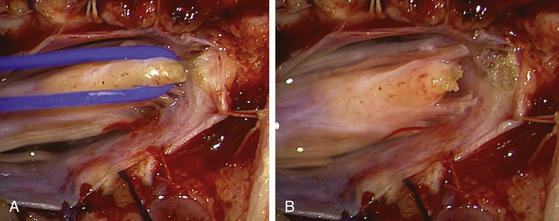

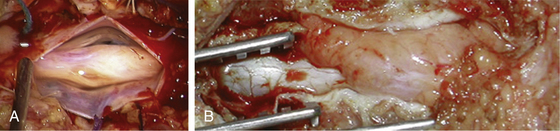

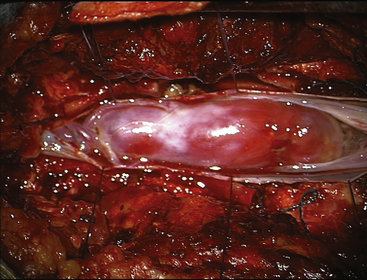

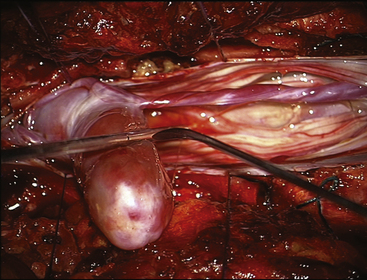

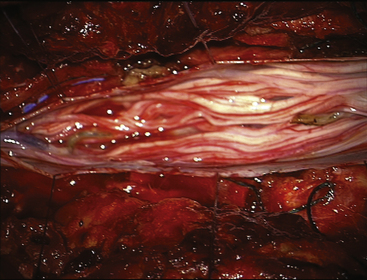

The dura mater may be absent in large ependymomas, and care must be taken not to injure the roots during the laminotomy. In the event of reoperation, laminectomy is unavoidable. The dura opening must allow control of the tumor’s extremities (Fig. 189-3), and the dura is fixed with stitches to the muscles. Dividing the tumor under optic magnification may begin. The best way to proceed is to start at the upper limit of the tumor, proceed inferiorly to the lower (Fig. 189-4), and to finish at the central part of the tumor. This strategy allows optimal root control (Fig. 189-5). Most of the roots are pushed against the dura by the tumor. Tumors of the filum terminale displace the roots on the right and left sides of the spinal canal, but they can develop between the roots, covering and hiding them. It is important to identify the filum, and stimulation can help do this.

FIGURE 189-3 Operative view showing exposure of both extremities of a cauda equina paraganglioma after opening of the dura mater.

FIGURE 189-4 Operative view of the same patient as Figure 189-3 showing debulking of the superior pole of the tumor.

FIGURE 189-5 Operative view of the same patient as in Figures 189-3 and 189-4 demonstrating root preservation after tumor removal.

After complete tumor removal and careful hemostasis, the dura is closed. A dural graft is often necessary.7 The spine is reconstructed and the lumbar aponeurosis is attached to the spinous processes. It is recommended that one leave some aponeurosis attachment during the opening to facilitate this type of closure (Fig. 189-6). The subcutaneous fat and skin are closed as usual. The use of tissue glue is left to the preference of the surgeon. All the removed material is sent for histopathologic examination.

Histologic Findings and their Consequences

Adult Pathology

Neurinomas (Schwannomas)

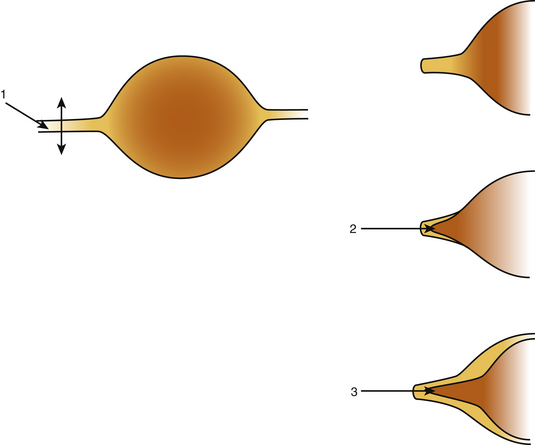

Neurinomas can develop purely inside the spinal canal or simultaneously in the foramen (hourglass type), which can cause an enlargement of the neural foramen seen on neuroimaging. On CT scan and MRI there is homogeneous enhancement (Figs. 189-7 and 189-8). The tumor is well encapsulated, and complete removal can be achieved in most cases. Magnification allows identification of the rootlet bearing the tumor and preservation of the other roots (Fig. 189-9). The bearing rootlet is cut 1 cm above and 1 cm below the tumor, some very small satellite tumors or tumor prolongments being at times in close proximity to the tumor.

FIGURE 189-8 Magnetic resonance image (MRI) of the same patient as Figure 189-7, exhibiting strong homogeneous enhancement after injection of contrast medium.

Neurofibromas are present only in association with neurofibromatosis8 and often occur in multiple locations. Surgery requires the removal of several roots and gives poor results. It is the only form of CET requiring pure symptomatic medical management. Malignant evolution is possible and leads to death in a few months.

Ependymomas

The myxopapillary type of ependymoma is characteristic of the cauda equina and arises from the filum terminale below the conus. In a few cases it can develop from the distal part of the filum inside the sacrum9,10 (Fig. 189-10).

Ependymoma occurs in patients younger than those harboring neurinomas. The average age is 34.6 years ±16 years, and there is a slight male predominance (61%). The time interval prior to diagnosis is the same and for the same reasons: It is slow-growing, and it can reach giant proportions, filling the lumbar and sacral canal. This benign tumor is often hemorrhagic, with rupture of its walls, and tumor implants in other parts of the spinal canal and can even spread inside the skull. A complete MRI exploration of the central nervous system is strongly recommended.11–12

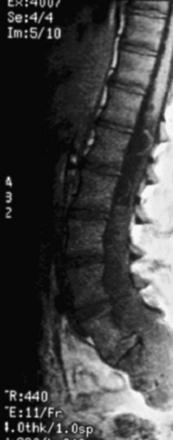

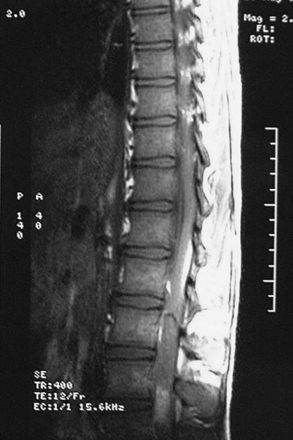

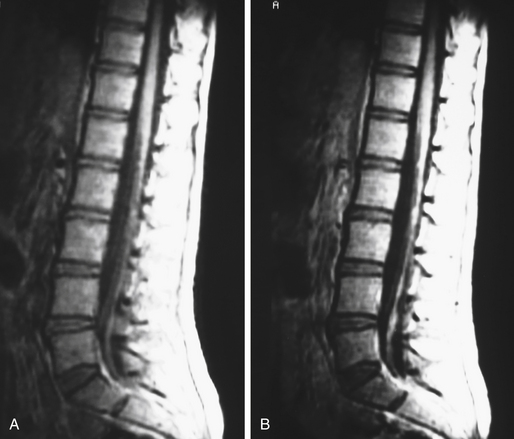

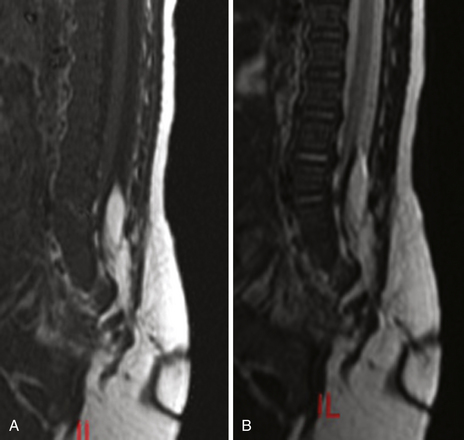

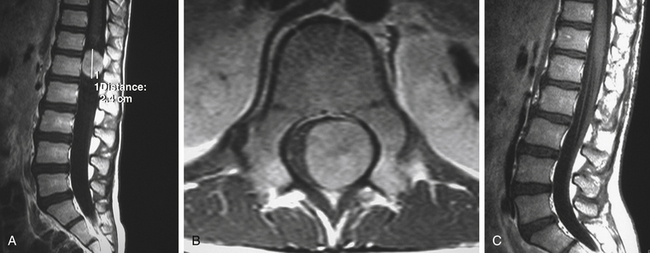

Scalloping is found on radiography in 22% of patients. In many patients a CT scan was performed a year or more before the diagnosis and was normal. This is because the level of the spine examined was below the level of the tumor or because hypodense tumor had completely filled the dura and was not identified as tumor. MRI demonstrates a generally hypointense signal on T1-weighted sequences (Fig. 189-11) and a hyperintense one on T2-weighted sequences (Fig. 189-12), often with heterogeneity due to hemorrhage and cystic changes inside the tumor. Those hemorrhages appear as hyperintense on T1 sequences (Fig. 189-13). After gadolinium injection, enhancement is often homogeneous, except in hemorrhagic zones (Fig. 189-14). Large drainage veins exist and contribute to the identification of these hypervascularized lesions.

FIGURE 189-12 Sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance image (MRI) sequence of the same patient as in Figure 189-11. The tumor appears hyperintense and slightly unhomogeneous. Scalloping at the L4, L5, S1 levels is marked.

FIGURE 189-14 Sagittal T1-weighted magnetic resonance image (MRI) sequence of the same patient as in Figures 189-11 and 189-12, after gadolinium injection, demonstrating strong enhancement.

Total removal was achieved in 85% of the patients in our series. The clinical outcome is often problematic: 23% still have sphincter disturbance and 9% need help for walking after 1 year. Turmors recurred in 14 patients (17%) 3 months to 25 years after the first surgical treatment. These cases always require reoperation because of neurologic deterioration, especially with regard to urinary and genital functions. Postoperative radiotherapy is no longer prescribed when total removal has been achieved, given the potential late after radiotherapy for complications in a young population. In the case of recurrence, patients require reoperation and often undergo radiation therapy. Irradiation is indicated in aggressive forms with early and multifocal recurrence.13 No chemotherapy has been shown to be of value in these cases. Recurrences are not particularly more difficult to remove, but most of the time the clinical postoperative outcome is worse than after the first operation, especially with regard to sphincter and genital functions.

Paragangliomas

Paragangliomas are benign tumors representing 3.8% of the tumors in our series.1,2 In only one case did the tumor undergo malignant progression.14 Paragangliomas occur most commonly in the head and neck region and originate in the jugular glomus, deriving from the APUD system. They can be found nearly everywhere in the body. In the central nervous system, they can develop in the pineal or pituitary glands, in the cerebellopontine angle, and in the cauda equina and the filum terminale.

There is a male predominance: 62% versus 38%.15 About 100 cases have been reported in the literature since 1980. Paragangliomas involve adults and young people: mean age is 49 years (range, 13 to 70 years).

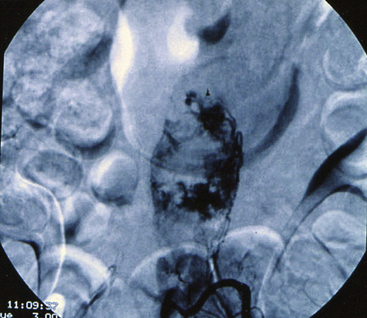

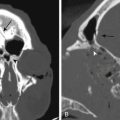

There are no specific features, and patients usually present with low back pain or sciatica or both. Functional hormonal activity has been described only in one case in spite of the neuroendocrine origin. On MRI the lesion is hypo- or isointense to the conus medullaris on T1-weighted sequences, is hyperintense on T2, and is sometimes inhomogeneous, with cysts. There is a marked enhancement after gadolinium injection (Figs. 189-15 and 189-16), and sometimes large vessels are seen around the tumor. Hemosiderin may be present, indicating previous hemorrhage. Selective angiography demonstrates a highly vascular mass in the early arterial series, and selective embolization can simplify surgery.

FIGURE 189-16 Axial T1-weighted magnetic resonance image (MRI) sequence of the same patient as in Figure 189-15 following contrast injection.

At surgery the tumor is a soft, red, well-circumscribed lesion originating from the filum (85%) (Fig. 189-17). Generally, complete removal can be achieved, but in a few cases adherence to the conus or the root leaves some small remnants of tumor.

Hemangioblastomas

Hemangioblastomas account for less than 1% of our series of CETs. The clinical and radiologic presentation is like that of a paraganglioma.16–17 Hypervascularity of the tumor can cause troublesome intraoperative bleeding. In one of our cases the procedure was stopped, the lesion was embolized, and resection was performed at a second stage (Figs. 189-18 to 189-20). This patient had a recurrence 3 years later and underwent reoperation. The patient is recurrence free at 7 years, with a good functional result. The origin of hemangioblastomas is not clearly established and might not be associated with Von Hippel-Lindau disease.18

Metastasis to the Cauda Equina

Metastases to the cauda equina are not true CETs.19–20 Multiple localizations (bunch of grapes) are the rule, with dissemination along the roots, and strong gadolinium enhancement on MRI (Fig. 189-21). Sometimes these tumors arise during the evolution of another tumor of the central nervous system that spreads inside the CSF (e.g., ependymoma, pineal tumor, medulloblastoma). Surgery is seldom indicated, and its main purpose is to establish histopathologic diagnosis. Radiotherapy is nearly always indicated, and chemotherapy is adapted to the histology.

Pediatric Group

Antenatal

Dermoid Cysts

Usually, dermoid and epidermoid tumors arise from the expansion of a dermal sinus, but they may be isolated when they develop from congenital vestigium or occur as the iatrogenic complication of implantation of viable dermal or epidermal structures through spinal needles, through trocars, or when closing a myelomeningocele.22

Clinical presentation is unremarkable, but when a dermal sinus has been neglected, diagnosis is sometimes made at the time of infection of the tumor, which has become an abscess coexisting with bacterial meningitis (two cases in our series).23 These children are often in poor condition and are operated on emergently, and they often have severe sphincter disturbances.

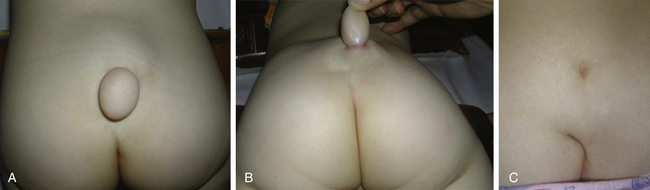

Newborns and Infants

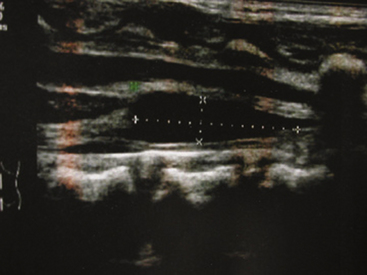

CET can be diagnosed with the help of skin markers of dysraphism, such as sacrococcygeal dimple, deviation of the gluteal cleft, lipomas, hypertrichosis, and midline angiomas in the lumbar region (Fig. 189-22). These markers need to be taken into account in order to perform radiologic workup, including spinal cord ultrasound before 3 months of age (Fig. 189-23) and spinal cord MRI after 3 months of age (Fig. 189-24). Ultrasound gives interesting data concerning the normal or lower position of the conus medullaris and the mobile or fixed spinal cord. At that time, neurologic deficits are not common, but the pediatric neurosurgeon prefers to operate on easy-to-remove lesions visible on radiologic examination, even in children with normal neurologic status (Figs. 189-25 and 189-26).

Lipomyelomeningocele or spinal lipoma may be considered real CETs,24 sometimes growing with obesity. Positive diagnosis is made with MRI scan (Fig. 189-27). Contrary to easy-to-remove lesions, spinal lipomas are often operated on only in children harboring neurologic deficits.25,26 This kind of lesion is really difficult to remove because the intraspinal lipoma and the termination of spinal cord are almost the same tissue, with a very intimate and extensive interface (Fig. 189-28 and 189-29).

When spinal lipoma is diagnosed in a child with a normal neurologic status, a strict clinical, electrophysiologic, and urodynamic workup is necessary in order not to miss the onset of mild neurologic signs such as sphincter disturbances or sensitivity or motor deficits in lower limbs, appearing during the child’s growth. The lipoma is often attached to the posterior part of the conus, and the nerve roots emerge laterally ventral to the lipoma-conus interface. The goal of such a surgery is to untether the cord, debulking and sectioning the lipoma, but its removal must be limited to avoid damage to the conus and to prevent worsening status in the patient. Otherwise, there is always a dural defect, and it is difficult to detach the lipoma while preserving the dura for a better closure. The most common complication of this procedure is CSF leak, and if the synthetic dura graft allows a total covering of the dural defect, it is not waterproof and cannot prevent late retethering of the cord. That is why we prefer not to use such grafts in favor of autologous muscular graft.

Older Children

Histologic findings are similar in older children and in adults, and in the literature we can find some ependymomas, meningiomas, and paragangliomas, but also metastases described in younger age groups (Fig. 189-30).

Technical Notes for Cauda Equina Tumors in Pediatric Patients

Approach to the Spine

Musculotendinous detachment from the spinous process and lamina is performed subperiosteally to limit blood loss.

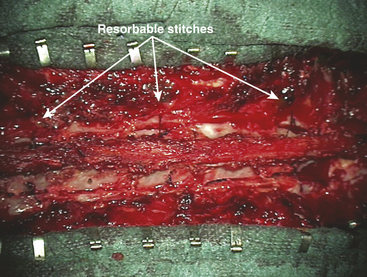

Two technical principles must be taken into account to avoid vertebral anterior displacement and postoperative complications by dura mater compression, especially in multilevel surgery. First, before approaching the spinous processes, the surgeon must preserve the supraspinal ligament to keep the whole vertebral flap in one piece. The supraspinal ligament is cut only at the bottom and the whole vertebral flap from the pedicle up is moved laterally, held by autostatic retractors, exposing the dura mater. This strong supraspinal ligament is necessary for the closure of the vertebral flap, using a solid wire to anchor the lower part of it. Second, after this anchorage, it is necessary to suture some laminae with resorbable wires (Fig. 189-31). At the end of the closure, the whole length of the supraspinal ligament is sutured with the lumbar fascia.

Follow-Up and Long-Term Outcome

MRI is the examination of choice for neuroradiologic follow-up. It must include T1- and T2-weighted sequences, postcontrast T1-weighted sequences, and at least two perpendicular planes (sagittal and axial), and it must involve the whole central nervous system except in solitary schwannomas. Early MRI is contributive only if carried out in the first two postoperative days. Postoperative changes often consist of linear or more-extensive contrast-enhancement nontumoral fibrosis, which can mimic or suggest tumor recurrence. Comparison of serial MRI, carried out twice a year, enables one to make the right diagnosis. For ependymomas there is no consensus with regard to the duration of the follow-up, because very late recurrences do exist. In all cases patients and their families must be aware of this eventuality and must contact their neurosurgeon if functional signs reappear.

Conclusion

CETs generally carry a favorable prognosis. Most of these tumors are benign, and the aim of treatment is to restore function and prevent recurrences. In our series, no postoperative or short-term death could be found. The one death during the 3 postoperative years was that of a patient with a malignant neurinoma. Five years after surgery, 92% of the patients were alive. Two patients (3.8%) with ependymomas died. The one suicide was in connection with a neurologic handicap. Very few patients needed adjuvant therapy.

Aghani N., George B., Parker F. Paraganglioma of the cauda equina region—report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Acta Neurochirurg (Wien). 1999;141:81-87.

Bayar M.A., Erdem Y., Tanyel O., et al. Spinal chordoma of the filum terminale. J Neurosurg (Spine). 2000;96:236-238.

Brisman J.L., Borges L.F., Ogilvy C.S. Extramedullary hemangioblastoma of the conus medullaris. Acta Neurochirurg (Wien). 2000;142:1059-1062.

Calvit M.F., Guzman A. Timing of surgery in patients with infected spinal dermal sinuses: report of two cases. Childs Nerv Syst. 1995:11:129-132.

Cordan T., Bekar A., Yaman O., et al. Spinal subarachnoid hemorrhage attributable to schwannoma of the cauda equina. Surg Neurol. 1999;51:373-375.

Fourney D.R., Fuller G.N., Gokaslan Z.L. Intraspinal extradural myxopapillary ependymoma of the sacrum arising from the filum terminale externa. J Neurosurg (Spine). 2000;93:322-326.

Gelabert-Gonzales M., Prieto-Gonzales A., Abdulkader-Nallib L., et al. Double ependymoma of the filum terminale. Childs Nerv Syst. 2001;17:106-108.

Hahn M., Hirschfeld A., Sander H. Hypertrophied cauda equina presenting as an intradural mass: case report and review of literature. Surg Neurol. 1998;49:514-519.

Hallacq P., Labrousse F., Streichenberg N., et al. Bifocal mixopapillary ependymoma of the terminal filum: the end of a spectrum? J Neurosurg. 2003;98(Suppl 3):288-289.

Kanev P.M., Park T.S. Dermoids and dermal sinus of the spine. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1995;6:359-365.

Kulkarni A.V., Bilbao J.M., Cusimano M.C., et al. Malignant transformation of ganglioneuroma into a spinal neuroblastoma in an adult. J.Neurosurg. 1998;88:324-327.

Lapierre F., Bataille B., Vandermarcq P., et al. Tumeurs de la queue de cheval chez l’adulte. Neurochirurgie. 1999;45:29-38.

Lellouch-Tubiana L., Zerah M., Catala M., et al. Congenital intra spinal lipomas: histological analysis of 234 cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 1999;2(4):346-352.

Locke J., True L.D. Isolated carcinoid tumor of the terminal filum. J Neurosurg (Spine). 2001;94:313-315.

Lonjon M., von Langsdorf D., Lefloch S., et al. Analyse des facteurs de récidive et rôle de la radiothérapie dans les épendymomes du filum terminale. Neurochirurgie. 2001;47:423-429.

Maxwell M., Borges L.F., Zervas N.T. Renal cell carcinoma: a rare source of cauda equina metastasis. J Neurosurg (Spine). 1999;90:129-132.

Nadkarni T.D., Rekate H.L., Coons S.W. Plexiform neurofibroma of the cauda equina. J Neurosurg (Spine). 1999;91:112-115.

Nowak D.A., Gumprecht H., Lumenta C.B. Intraneural growth of a capillary haemangioma of the cauda equina. Acta Neurochirurg (Wien). 2000;142:463-468.

Pierre-Kahn A., Zehra M., Renier D., et al. Congenital lumbosacral lipomas. Childs Nerv Syst. 1997;13(6):298-334. discussion 335

Ricket C.H., Kedziora O., Gullotta F. Ependymoma of the cauda equina. Acta Neurochirurg (Wien). 1999;141:781-782.

Russell D.S., Rubinstein L.J. Pathology of the Tumors of the Nervous System. London: Edward Arnold; 1990.

Sala F., Krzan M.J., Deletis V. Intra-operative neurophysiological monitoring in pediatric neurosurgery: why, when, how? Childs Nerv Syst. 2000;18:264-287.

Tibbs R.E., Harkey H.L., Raila F.A. Hemangioblastoma of the filum terminale: case report. Neurosurgery. 1999;14:221-223.

Tindall G.T., Cooper P.R., Barrow D.L. The Practice in Neurosurgery, 1 ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1996.

Wager M., Lapierre F., Blanc J.L., et al. Cauda equina tumors: a French multicenter retrospective review of 231 adult cases and review of the literature. Neurosurg Rev. 2000;23:119-129.

1. Lapierre F., Bataille B., Vandermarcq P., et al. Tumeurs de la queue de cheval chez l’adulte. Neurochirurgie. 1999;45:29-38.

2. Wager M., Lapierre F., Blanc J.L., et al. Cauda equina tumors: a French multicenter retrospective review of 231 adult cases and review of the literature. Neurosurg Rev. 2000;23:119-129.

3. Russell D.S., Rubinstein L.J. Pathology of the Tumors of the Nervous System. London: Edward Arnold; 1990.

4. Cordan T., Bekar A., Yaman O., et al. Spinal subarachnoid hemorrhage attributable to schwannoma of the cauda equina. Surg Neurol. 1999;51:373-375.

5. Hahn M., Hirschfeld A., Sander H. Hypertrophied cauda equina presenting as an intradural mass: case report and review of literature. Surg Neurol. 1998;49:514-519.

6. Sala F., Krzan M.J., Deletis V. Intra-operative neurophysiological monitoring in pediatric neurosurgery: why, when, how? Childs Nerv Syst. 2000;18:264-287.

7. Tindall G.T., Cooper P.R., Barrow D.L. The Practice in Neurosurgery, 1 ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1996.

8. Nadkarni T.D., Rekate H.L., Coons S.W. Plexiform neurofibroma of the cauda equina. J Neurosurg (Spine). 1999;91:112-115.

9. Ricket C.H., Kedziora O., Gullotta F. Ependymoma of the cauda equina. Acta Neurochirurg (Wien). 1999;141:781-782.

10. Fourney D.R., Fuller G.N., Gokaslan Z.L. Intraspinal extradural myxopapillary ependymoma of the sacrum arising from the filum terminale externa. J Neurosurg (Spine). 2000;93:322-326.

11. Gelabert-Gonzales M., Prieto-Gonzales A., Abdulkader-Nallib L., et al. Double ependymoma of the filum terminale. Childs Nerv Syst. 2001;17:106-108.

12. Hallacq P., Labrousse F., Streichenberg N., et al. Bifocal mixopapillary ependymoma of the terminal filum: the end of a spectrum? J Neurosurg. 2003;98(Suppl 3):288-289.

13. Lonjon M., von Langsdorf D., Lefloch S., et al. Analyse des facteurs de récidive et rôle de la radiothérapie dans les épendymomes du filum terminale. Neurochirurgie. 2001;47:423-429.

14. Kulkarni A.V., Bilbao J.M., Cusimano M.C., et al. Malignant transformation of ganglioneuroma into a spinal neuroblastoma in an adult. J. Neurosurg. 1998;88:324-327.

15. Aghani N., George B., Parker F. Paraganglioma of the cauda equina region—report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Acta Neurochirurg (Wien). 1999;141:81-87.

16. Tibbs R.E., Harkey H.L., Raila F.A. Hemangioblastoma of the filum terminale: case report. Neurosurgery. 1999;14:221-223.

17. Nowak D.A., Gumprecht H., Lumenta C.B. Intraneural growth of a capillary haemangioma of the cauda equina. Acta Neurochirurg (Wien). 2000;142:463-468.

18. Brisman J.L., Borges L.F., Ogilvy C.S. Extramedullary hemangioblastoma of the conus medullaris. Acta Neurochirurg (Wien). 2000;142:1059-1062.

19. Locke J., True L.D. Isolated carcinoid tumor of the terminal filum. J Neurosurg (Spine). 2001;94:313-315.

20. Maxwell M., Borges L.F., Zervas N.T. Renal cell carcinoma: a rare source of cauda equina metastasis. J Neurosurg (Spine). 1999;90:129-132.

21. Bayar M.A., Erdem Y., Tanyel O., et al. Spinal chordoma of the filum terminale. J Neurosurg (Spine). 2000;96:236-238.

22. Kanev P.M., Park T.S. Dermoids and dermal sinus of the spine. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1995;6:359-365.

23. Calvit M.F., Guzman A. Timing of surgery in patients with infected spinal dermal sinuses: report of two cases. Childs Nerv Syst. 1995;11:129-132.

24. Lellouch-Tubiana L., Zerah M., Catala M., et al. Congenital intra spinal lipomas: histological analysis of 234 cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 1999;2(4):346-352.

25. Pierre-Kahn A., Zehra M., Renier D., et al. Congenital lumbosacral lipomas. Childs Nerv Syst. 1997;13(6):298-334. discussion 335

26. Tseng J.H., Kuo M.F., Kwang T.Y., et al. Outcome of untethering for sympatomatic spina bifida occulta with lumbosacral spinal cord tethering in 31 patients: analysis of preoperative prognostic factors. Spine. 2008;8(4):630-638.