Malignant tumors of the epidermis

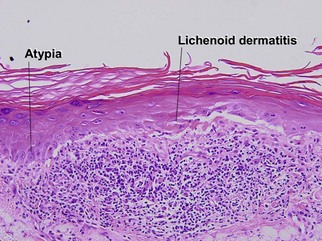

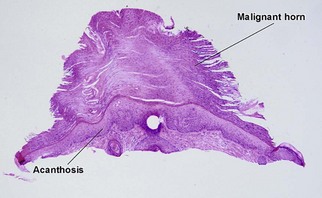

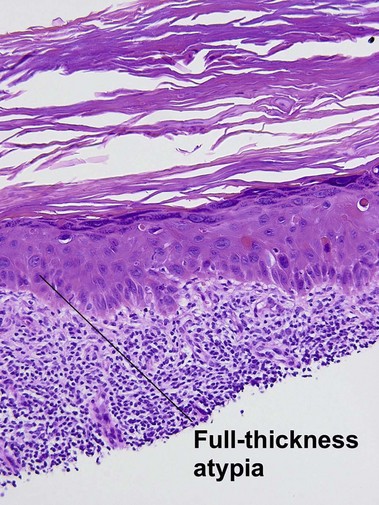

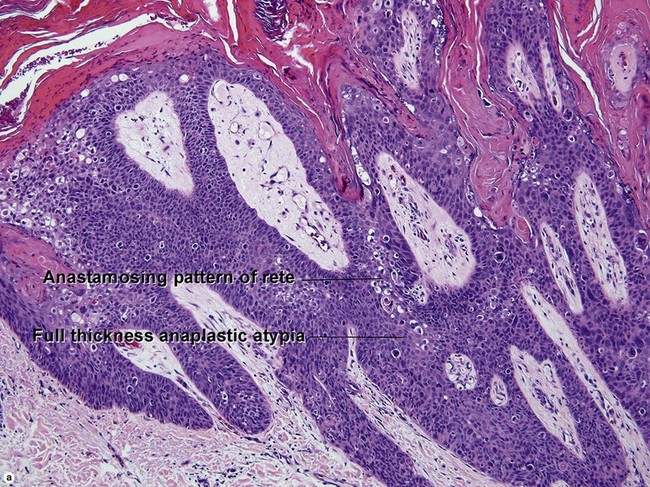

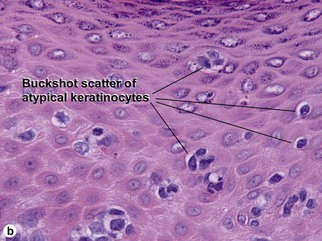

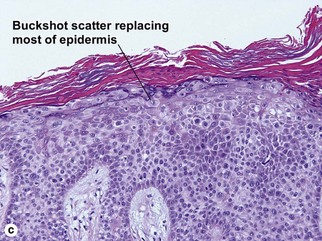

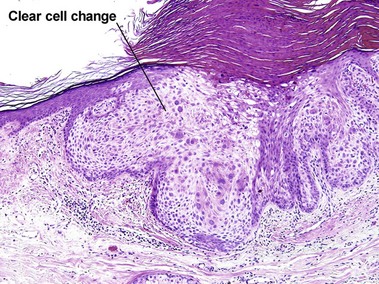

Bowen’s disease

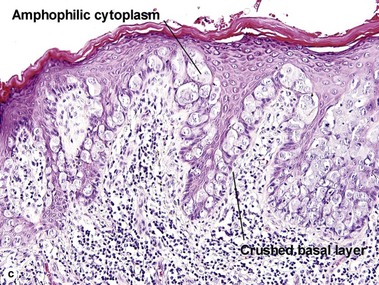

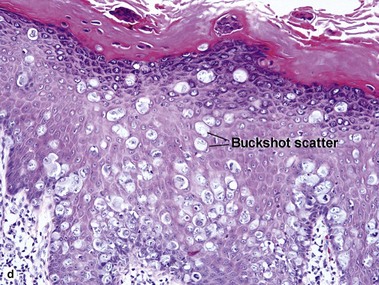

The malignant keratinocytes of Bowen’s disease can keratinize and become part of the stratum corneum. In contrast, the malignant cells of Paget’s disease or melanoma often “spit out” into the stratum corneum intact. Bowen’s disease contains glycogen and is periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) positive and diastase sensitive. In contrast, Paget’s disease contains sialomucin and is PAS positive, diastase resistant. Bowen’s disease is negative for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) whereas Paget’s stains for CEA. Ducts and sebaceous differentiation distinguish porocarcinoma and sebaceous carcinoma.

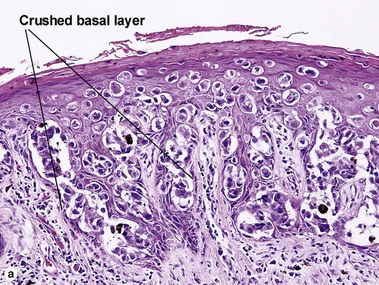

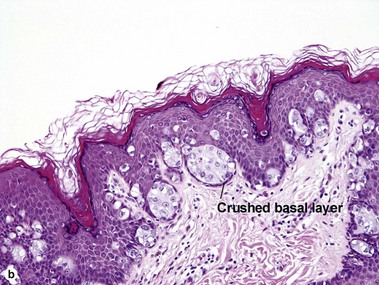

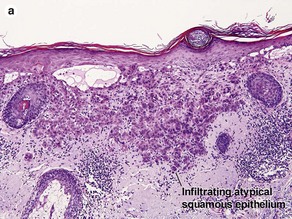

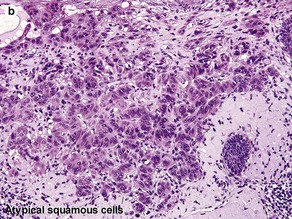

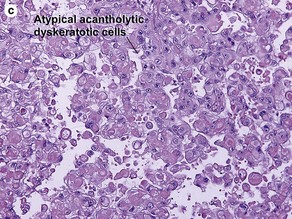

Squamous cell carcinoma

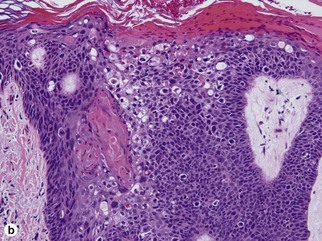

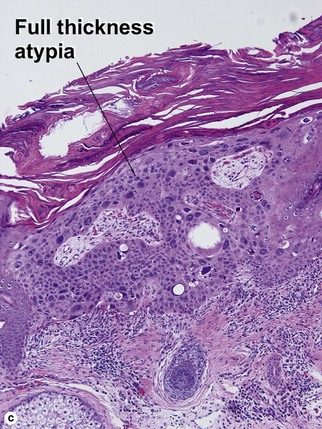

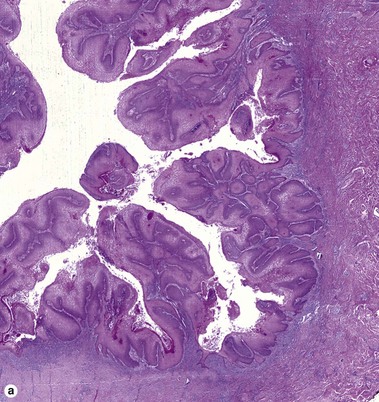

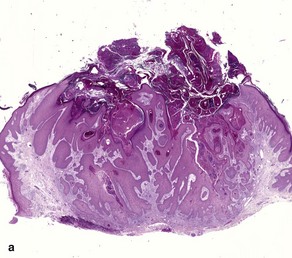

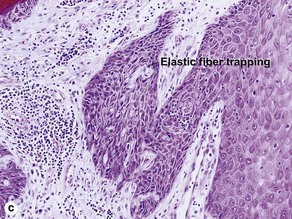

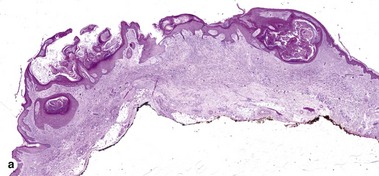

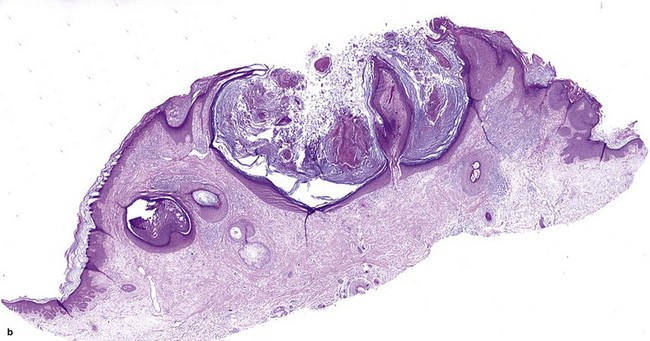

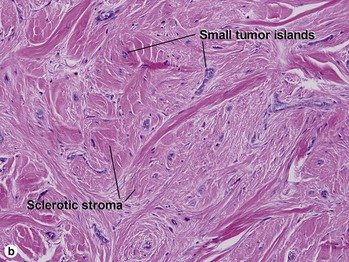

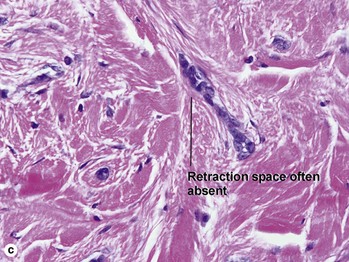

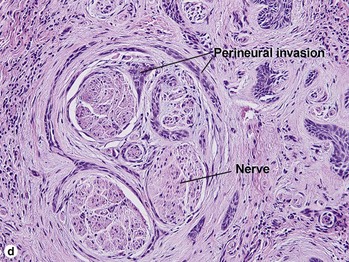

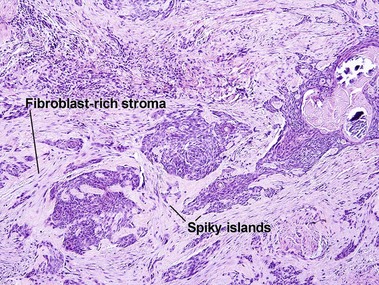

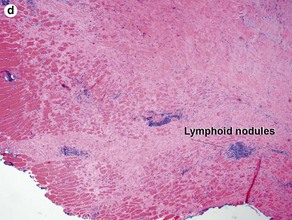

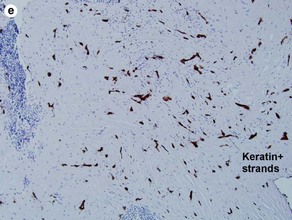

Fig 3-10 (a,b) Well-differentiated invasive squamous cell carcinoma. (c) Acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma. (d,e) Desmoplastic squamous cell carcinoma (H&E and keratin 907 immunostain)

Keratoacanthoma

Table 3-1

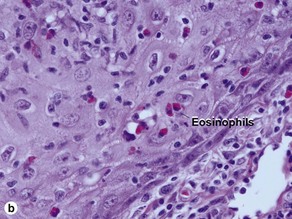

Characteristics of keratoacanthoma versus squamous cell carcinoma

| Characteristic | Keratoacanthoma | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and hypergranulosis | At center of lesion | At periphery of lesion |

| Cell type | Large light pink glassy cells | Often large, light pink and glassy |

| Dermal infiltrate | Eosinophils common | Plasma cells common |

| Gland involvement | Pushes eccrine glands down | Invades eccrine glands |

| Traps elastic tissue | Commonly | Rarely |

| Acantholysis | No | Often |

| Perineural invasion | Yes | Yes |

| Neutrophilic microabscesses | Common | Rarely |

| Growth | Explosive | Slow |

| Terminal differentiation | Yes | No |

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC)

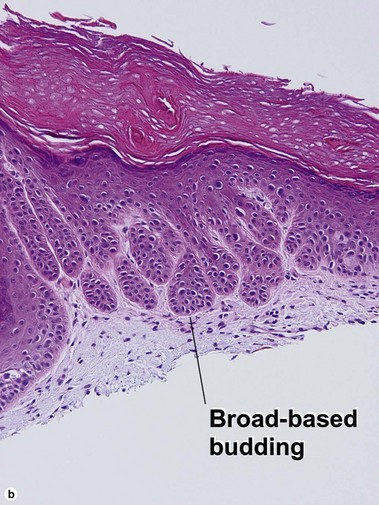

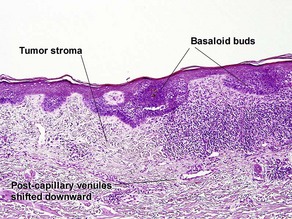

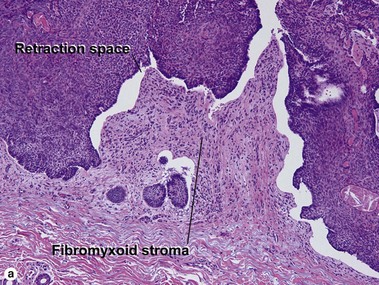

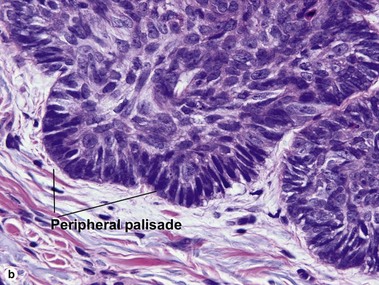

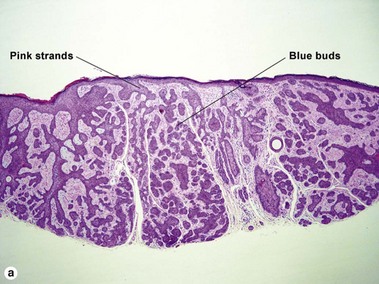

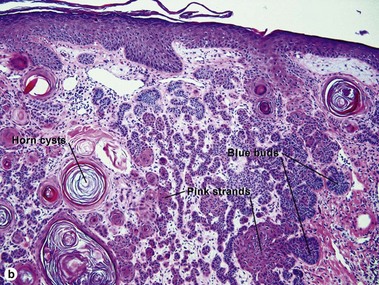

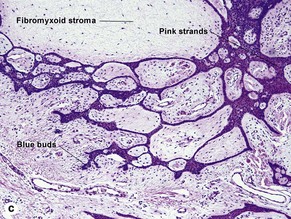

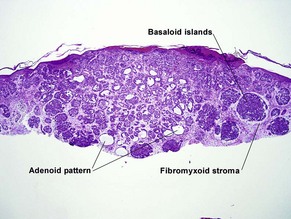

Superficial multifocal BCC

Superficial multifocal BCC grows in a pattern resembling garlands draped from the epidermis. In two-dimensional sections, this gives the appearance of multifocal blue buds. Because the buds are spaced far apart, margin evaluation is based largely on the surrounding tumor stroma. The tumor stroma displaces the reticular dermis and solar elastosis downward.

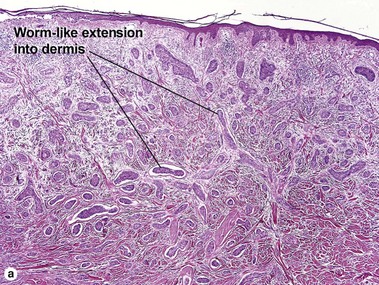

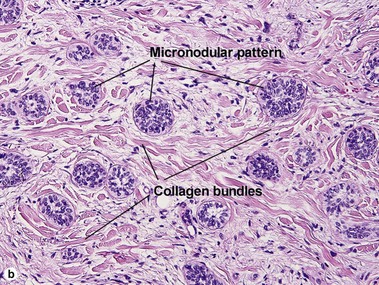

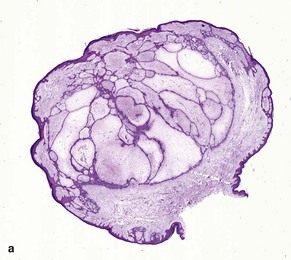

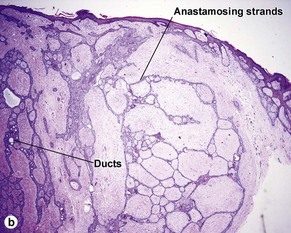

Micronodular BCC

Micronodular BCC is characterized by aggressive worm-like growth into the dermis. In cross-section, the appearance is micronodular. Because of the thick dermal collagen bundles between tumor islands, the tumors are poorly defined clinically, and curettage has a high failure rate.

Infiltrative BCC

At first glance, the fibroblast-rich stroma of an infiltrative BCC can resemble the stroma of a trichoepithelioma. Glance again. Trichoepitheliomas never have spiky islands. If you remember that spiky things are likely to hurt you, it may help you to remember that this feature matches with an aggressive form of BCC. Papillary mesenchymal bodies are absent in infiltrative BCC.

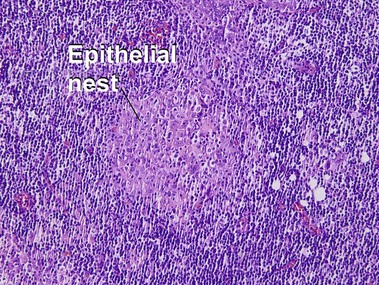

Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma

Despite the anaplastic character of the cells, the prognosis is generally good. Nasopharyngeal lymphoepithelioma can have a similar appearance, and metastatic disease should be ruled out. Cutaneous lesions are EBV negative, unlike the nasopharyngeal counterpart.

Cigna, E, Tarallo, M, Sorvillo, V, et al. Metatypical carcinoma of the head: a review of 312 cases. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012; 16(14):1915–1918.

Hernandez-Perez, E, Figueroa, DE. Warty and clear cell Bowen’s disease. Int J Dermatol. 2005; 44(7):586–587.

Mengjun, B, Zheng-Qiang, W, Tasleem, MM. Extramammary Paget’s disease of the perianal region: a review of the literature emphasizing management. Dermatol Surg. 2013; 39(1 Pt 1):69–75.

Rubin, AI, Chen, EH, Ratner, D. Basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2005; 353(21):2262–2269.

Rudolph, R, Zelac, DE. Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004; 114(6):82e–94e.

Sah, SP, Kelly, PJ, McManus, DT, et al. Diffuse CK7, CAM5. 2 and BerEP4 positivity in pagetoid squamous cell carcinoma in situ (pagetoid Bowen’s disease) of the perianal region: a mimic of extramammary Paget’s disease. Histopathology. 2013; 62(3):511–514.