Chapter 40 Malignant Melanoma

In the early 1930s, when categorizing tumor radiosensitivity gained widespread acceptance, melanoma was considered to be categorically radioresistant. This belief was perpetuated by popular textbooks of the time until laboratory data showed that the reputed radioresistance of melanoma might reflect a broad shoulder in the low-dose portion of the cell survival curve. The data suggested that melanoma cells might be more sensitive to radiation delivered as a large dose per fraction (i.e., hypofractionation regimen). Although a randomized trial performed by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) did not confirm clinical superiority for hypofractionation in a heterogeneous group of patients receiving palliative radiation therapy, these types of regimens are favored by clinicians specializing in melanoma radiation therapy.1 Retrospective reviews of clinical experiences have suggested that the hypofractionated regimens are effective and can be safely delivered in a short period of time to a group of patients for whom survival is ultimately dictated by the risk of distant metastasis.2,3

Etiology and Epidemiology

For 2010, 68,130 new cases of cutaneous malignant melanoma were estimated, or 5% of all newly diagnosed cancers.4 Although the incidence of malignant melanoma more than doubled between 1975 and 2000, new cases of melanoma are being diagnosed earlier in the course of the disease because of increased public awareness, and the mortality rate has steadily decreased.4 The reason for the rise in incidence has not been explained. The number of deaths due to melanoma in 2010 was estimated to be 8700.

Several lines of evidence link sun or ultraviolet (UV) radiation exposure to the development of cutaneous melanoma.5,6 There is a higher incidence of melanoma in populations living in areas of high ambient sunlight, among sun-sensitive people, on sun-exposed body sites, in populations with high sun exposure, and among people with other sun-related skin conditions.7,8 The development of melanoma may also be reduced by protection of the skin against sun exposure.7

Analysis of patients with familial clustering of melanoma has identified two genes, CDKN2A and CDK4, that confer increased susceptibility to melanoma development.9 Although only a small percentage of patients with melanoma has a mutation in CDKN2A, carriers of this mutation have an almost 70% chance of developing melanoma by the age of 80 years.10,11

The presence of an increasing number of nevi also represents a well-accepted risk factor for the development of melanoma.12 Whether the type of nevi (i.e., common, atypical, or dysplastic) is also important or merely reflects the degree of previous sun-related damage remains controversial.

Prevention and Early Detection

A panel of the American College of Preventive Medicine (ACPM)13 performed a thorough review of the medical literature and issued a practice policy statement regarding skin cancer prevention. Recommended preventive measures include avoidance of sunlight exposure—particularly limiting time spent outdoors between 10 AM and 3 PM—and wearing protective physical barriers such as hats and clothing. If sun exposure cannot be limited because of occupational, cultural, or other factors, the use of sunscreens that are opaque or that block ultraviolet A and B radiation is recommended.

Clinical Manifestations, Pathobiology, and Pathways of Spread

Clinical Presentation and Pathology

Primary cutaneous melanoma may develop in or adjacent to one of the precursor lesions (e.g., lentigo maligna, dysplastic nevus) or in normal skin, and it can manifest clinically in four major growth patterns.14 The most prevalent variant is superficial spreading melanoma, which constitutes approximately 70% of cases.15,16 This growth pattern can occur at any age after puberty and affects women more frequently than men. Superficial spreading melanoma often arises in a junctional nevus, where it first appears as a deeply pigmented area, progressing gradually to a flat induration, generally over several years. There are often patches of amelanotic areas within the lesion thought to result from focal regression. As the lesion grows, the surface and perimeter may become irregular. On histologic examination, it is characterized by a prominent intraepidermal proliferation of malignant melanocytes. The malignant cells resemble the cells of Paget’s disease; hence, this pattern is called pagetoid melanoma.17 The malignant cell may be confined to the lower portion of the epidermis or may spread up into the granular cell layer of the epidermis, which is frequently hyperplastic. As the lesion enlarges, clusters of malignant cells invade the dermis and subcutaneous tissues.

Nodular melanoma is the second most common variant (15% to 25% of melanoma lesions).15,16 Nodular melanoma develops more frequently de novo on the trunk, head, or neck of middle-aged individuals. In contrast to superficial spreading melanoma, the nodular variant affects men more than women. It manifests as a raised or dome-shaped, blue-black lesion, which is usually darker than superficial spreading melanoma. Approximately 5% of nodular variants manifest as nonpigmented, fleshy nodules, and, therefore, this type of lesion is called amelanotic melanoma. Histologic testing shows that nodular melanoma is characterized by an expansile nodule centered at the papillary dermis, with little or no epidermal component, composed of epithelioid cells. Spindle cells, small epithelioid cells, and mixtures of cells may be present. Deeper invasion of the dermis and subcutis occurs as the lesion grows.

Lentigo maligna melanoma is seen in less than 10% of malignant melanoma lesions.16,18 This variant occurs most frequently on the face or neck of white women older than 50 years, and it arises from a precursor lesion of melanoma in situ called lentigo maligna (i.e., Hutchinson’s melanotic freckle).19 It manifests as a relatively large (>3 cm), flat, tan-colored (with different shades of brown) lesion that often has been present for more than 5 years. The border becomes irregular as the lesion enlarges. On histologic examination, an invasive tumor is usually composed of spindle-like cells. These cells may be embedded in a fibrous stroma (i.e., desmoplastic pattern) or may form fascicles displaying neural features and infiltrating endoneural and perineural structures of the cutaneous nerves.19,20

Acral lentiginous melanoma occurs characteristically on the palms or soles or beneath nail beds.21–23 The relative frequency of acral lentiginous melanoma varies substantially with race. It represents about 5% of melanomas in white individuals and 35% to 60% in dark-skinned individuals.24,25 Most acral lentiginous melanomas occur on the foot sole in individuals older than 60 years. They generally start as tan or brown stains and evolve over a period of years to reach an average diameter of 3 cm before a diagnosis is established.22,23 Histologic testing reveals that early-stage acral lentiginous melanoma is composed of large, highly atypical, pigmented cells along the dermoepidermal junction in an area of hyperplastic epidermis. At the invasive stage, infiltrating cells may be epithelioid or spindle shaped.20 Sometimes, infiltration to deeper structures occurs, predominantly through the eccrine ducts.17

Biology and Patterns of Spread

Previously, two microstaging systems were used. The Breslow system classifies lesions by the vertical thickness between the granular layer of the epidermis and the deepest part of invasion, measured with an ocular micrometer. In ulcerated lesions, measurements are made from the surface to the deepest part.26 The Clark method categorizes lesions into five groups by the level of dermal or subcutis invasion: level I, confined to the epidermis; level II, invasion to the papillary dermis; level III, invasion to the papillary-reticular dermal interface; level IV, invasion to the reticular dermis; and level V, invasion to the subcutaneous tissue.15 Of the two systems, tumor thickness is more accurate in predicting outcome, although level of invasion remains prognostic for patients with lesions less than 1 mm thick.27

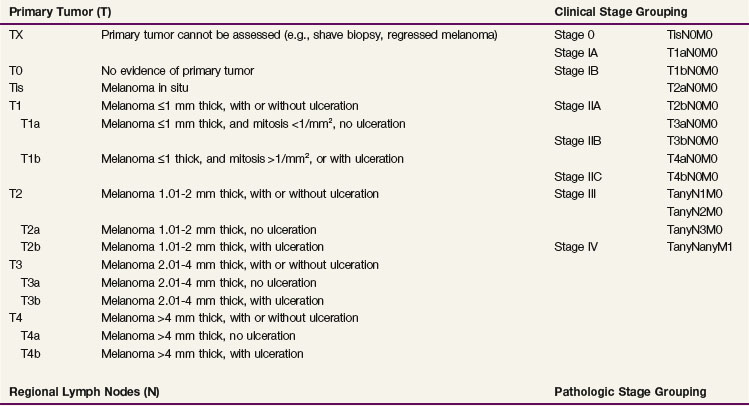

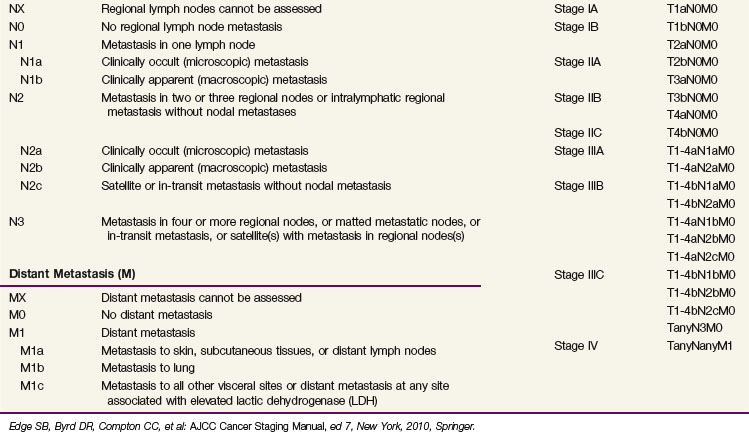

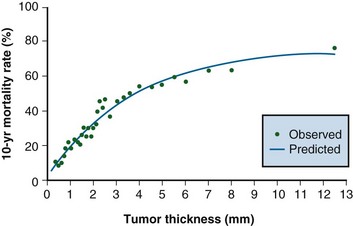

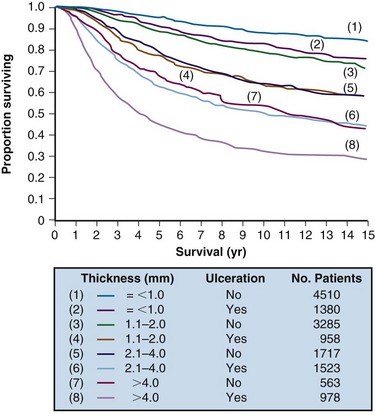

In an analysis of 17,600 patients with melanoma, several clinical and histologic variables were found to be of prognostic value, and they formed the basis for an updated American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system27,28 (Table 40-1). For patients without clinical evidence of nodal spread, primary thickness and ulceration were the most important prognostic features. The 10-year melanoma-specific mortality increased proportionally as the thickness of the primary tumor increased (Fig. 40-1), and the survival of patients with ulcerated primary lesions diminished to a level equivalent to that of patients with thicker primary lesions that were not ulcerated27 (Fig. 40-2). There was significantly inferior 10-year disease-specific survival (DSS) according to site of the primary lesion (i.e., worse for trunk, head, and neck lesions than extremity lesions), gender (i.e., worse for male than female patients), and age (i.e., worse for older than younger patients).27

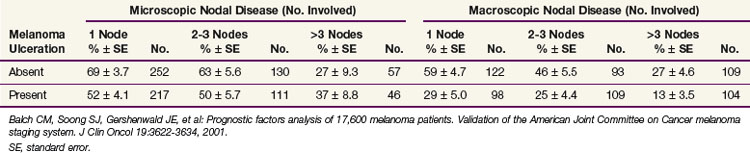

For patients with documented nodal metastases, the most important prognostic feature was the number of involved lymph nodes, but primary tumor ulceration and burden of nodal disease (microscopic vs. macroscopic) remained of prognostic significance on multivariate analysis27 (Table 40-2). Patients with skin, subcutaneous, and distant lymph node metastases fared better than those with visceral metastases.27

Patient Evaluation and Staging

Suggested staging guidelines for patients with melanoma are shown in Table 40-3. Clinical evaluation of patients with melanoma consists of inspection and palpation of the involved area of skin and the regional lymph nodes. Patients with primary lesions 1 mm thick or larger are generally staged at the time of wide local excision with sentinel lymph node biopsy. Patients with thinner lesions may still be at risk of nodal disease and may benefit from sentinel lymph node biopsy if the primary lesion is ulcerated, is associated with satellitosis, or is Clark level IV or V. Imaging studies (i.e., CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis or MRI studies of the brain) should be obtained as indicated by the result of immunohistochemical examination of the sentinel node. If the sentinel node is involved, CT scanning of the lungs, abdomen, and pelvis is warranted as a baseline evaluation.29

| Disease Presentation | Workup |

|---|---|

| Primary lesion <1 mm, and Clark level II-III, and not ulcerated | History and physical examination* |

| Primary lesion ≥1 mm, or Clark level IV-V, or ulcerated | History and physical examination* |

| Sentinel lymph node biopsy | |

| Microscopic nodal metastases | History and physical examination* |

| Chest radiograph and serum LDH level | |

| Further imaging if warranted | |

| Macroscopic nodal metastases | History and physical examination* |

| Serum LDH level | |

| CT imaging of chest, abdomen, pelvis | |

| CT imaging of head and neck if primary tumor above clavicles | |

| Consider brain MRI | |

| Further imaging if warranted | |

| Distant metastases | History and physical examination* |

| Chest radiograph and serum LDH level | |

| CT imaging of chest, abdomen, pelvis | |

| CT imaging of head and neck if primary tumor above clavicles | |

| Brain MRI | |

| Further imaging if warranted |

CT, computed tomography; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

* Attention to comprehensive skin and nodal basin examination.

Primary Therapy and Results

Primary Tumor

Standard treatment for localized melanoma (stages I and II) is wide local excision. Wide local excision is a therapeutic intervention, but it also establishes tissue diagnosis and provides accurate microstaging. Five randomized trials have examined the appropriate width of excision for primary melanoma.30–33,34 The recommended skin margins are 1 cm for lesions less than 1 mm thick and 2 cm for melanomas 1 mm or thicker.34,35

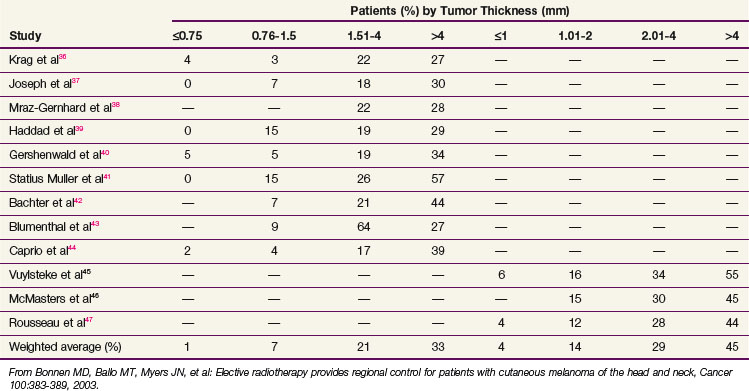

Sentinel lymph node biopsy is recommended according to the aforementioned criteria (see Patient Evaluation and Staging). This procedure provides accurate nodal staging, but it should be followed by nodal irradiation (see Regional Nodes) or formal lymph node dissection if the sentinel node is involved. The rate of nodal spread according to primary thickness is shown in Table 40-4; it is less than 5% for lesions 0.75 mm or smaller, 10% for lesions 0.76 to 1.5 mm, 20% for lesions 1.51 to 4 mm, and 30% to 50% for lesions larger than 4 mm.36–44,45,46,47

Radiation therapy is not indicated as definitive management of primary malignant melanoma. An exception to this rule is large facial lentigo maligna melanomas for which wide surgical resection may require extensive reconstruction. In a series of 25 patients treated at the Princess Margaret Hospital with primary radiation therapy and followed for a period of 6 months to 8 years (median, 2 years), local control was achieved in 23 patients (92%).48 The median time to complete regression of lesions was 8 months, and some lesions took 2 years to disappear. Radiation treatment was delivered with orthovoltage x-rays (100 to 250 KeV), and regimens used were 35 Gy in 5 fractions over 1 week for lesions smaller than 3 cm, 45 Gy in 10 fractions over 2 weeks for primary tumors of 3 to 4.9 cm, and 50 Gy in 15 to 20 fractions over 3 to 4 weeks for tumors 5 cm or larger.

Irradiation is rarely recommended as an adjuvant to wide local excision. Local recurrence in the five randomized trials examining margin width for primary lesions ranged from less than 1% to 8% of patients.30–33,34 Although high-risk features such as primary thickness greater than 4 mm, head or neck primary site, and primary ulceration or satellitosis have been reported to significantly increase the risk of local recurrence, few series report recurrence rates much higher than 15%32,49–60 (Table 40-5).

TABLE 40-5 Local Recurrence after Surgery Alone for Primary Tumor According to High-Risk Pathologic Characteristics

| Characteristic | % | References |

|---|---|---|

| Breslow thickness ≥4 mm | 6 to 14 | 35, 49-53 |

| Head and neck location | 5 to 17 | 32, 49, 50, 52, 54-58 |

| Ulceration | 10 to 17 | 32, 35, 50, 52 |

| Satellitosis | 14 to 16 | 59, 60 |

Adapted from Ballo MT, Ang KK: Radiotherapy for cutaneous malignant melanoma. Rationale and indications, Oncology 18:99-107, 2004.

One variant of melanoma, the desmoplastic subtype, has historically been associated with recurrence rates as high as 50% after wide local excision alone.61–66,67,68 One series specifically examining the role of radiation therapy in 44 patients with desmoplastic melanoma reported recurrence rates of 48% (21 of 44 patients) without irradiation and 0% (0 of 14 patients) with irradiation.67

More contemporary surgical series have reported recurrence rates of little more than 10% after careful pathologic examination of resection margins, bringing into question the routine use of adjuvant radiation therapy.69–72 Based on these experiences, we acknowledge the efficacy of radiation therapy but are selective in our recommendations. We reserve radiation therapy for patients with positive resection margins, Clark level IV disease or greater, Breslow thickness of more than 4 mm, and head and neck location, particularly when margins are narrow and recurrence might be difficult to salvage.

Regional Nodes

Elective Nodal Treatment

The role of elective nodal therapy at the time of wide local excision of the primary tumor has been disputed extensively. Advocates of elective lymph node dissection argue that melanoma progresses in a stepwise fashion from the primary lesion to regional nodes and then to distant sites, whereas opponents suggest that positive regional lymph nodes are only indicators of systemic spread. Results of an early nonrandomized study by the Sydney Melanoma Unit involving 1319 patients suggested that elective lymph node dissection improved the survival rates of patients with intermediately thick melanomas (0.76 to 4 mm).73 Four prospective phase III trials, however, have not confirmed these results. The first trial, conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO) Melanoma Group, randomized 553 patients to receive wide local excision and elective lymph node dissection or wide local excision and delayed therapeutic lymphadenectomy (i.e., lymph node dissection only if regional nodes became clinically detectable), and results showed no difference in the survival rates for the two groups.74 A smaller trial, performed at the Mayo Clinic, showed results similar to those of the WHO group.75

An Intergroup Melanoma Surgical Trial enrolled 740 patients with clinically localized melanomas of 1 to 4 mm and revealed no significant difference in 10-year overall survival (OS) between patients randomized to receive elective lymph node dissection or observation (77% vs. 73%; p = .12). Significant differences in OS were observed, however, in subsets of patients as old as 60 years (81% with elective lymph node dissection vs. 74% with observation; p = .03), particularly when they had nonulcerative tumors (84% vs. 77%; p = .03) and had melanomas 1 to 2 mm thick (86% vs. 80%; p = .03).76 A second WHO Melanoma Trial enrolled patients with trunk melanomas thicker than 1.5 mm to elective lymph node dissection or delayed dissection at the time of regional recurrence. This trial demonstrated a trend toward improved survival in the immediate-dissection arm (p = .09).77

The surgical community has embraced sentinel lymph node biopsy with selective lymph node dissection as a replacement to elective lymph node dissection, despite no reported therapeutic benefits in terms of OS. This choice depends on several lines of reasoning.78,79 The status of the sentinel lymph node is a powerful determinant of subsequent survival and provides prognostic information to the patient; it identifies patients with early regional lymph node metastases that might benefit from nodal dissection as a way of avoiding advanced regional recurrence; and it identifies patients who may be candidates for investigational systemic therapy trials.

Morton and colleagues80 randomly assigned 1269 patients with intermediate-thickness primary melanoma to wide excision and postoperative observation of regional lymph nodes with lymphadenectomy if nodal relapse occurred, or to wide excision and sentinel lymph node biopsy with immediate lymphadenectomy if nodal micrometastases were detected on biopsy. This trial, known as the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial (MSLT-I), reported improved 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) when patients undergoing sentinel lymph node biopsy with selective lymph node dissection were compared with patients who were observed. There were no differences in melanoma-specific survival. In a subgroup analysis confined to patients with nodal metastases, there was improved melanoma-specific survival in patients undergoing immediate lymphadenectomy compared with those in whom delayed lymphadenectomy was required for recurrent disease. Although the validity of this postrandomization analysis has been questioned by many,81 the prognostic information provided by sentinel lymph node biopsy was confirmed, and the improvement in DFS was sufficiently important to recommend sentinel lymph node biopsy with selective lymphadenectomy as the standard of care.

Although this remains the standard approach to patients with early-stage melanoma, there are some patients with significant medical comorbidities for whom detailed prognostic information is of little relevance and enrollment in a clinical trial is unlikely. For these patients, elective nodal irradiation is superior to observation, which places the patients at unnecessary risk of regional recurrence.82 In a retrospective analysis from the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Bonnen and colleagues83 reviewed 157 patients with stage I or II cutaneous melanoma of the head and neck who received elective regional irradiation instead of lymph node dissection after wide local excision of the primary site. Indications for regional irradiation included primary thickness of 1.5 mm or greater or Clark level IV or V disease. There were 15 regional failures (89% regional control at 10 years) despite an estimation that 33 to 40 patients had microscopically involved regional nodes (based on data from Table 40-4). Six percent of patients required medical care for a clinically significant complication, with moderate hearing loss being the most common complaint (five patients). Although elective nodal irradiation has the same limitations as elective lymph node dissection, it can effectively provide regional control for patients at risk for regional recurrence while avoiding surgical dissection.

Therapeutic Nodal Approaches

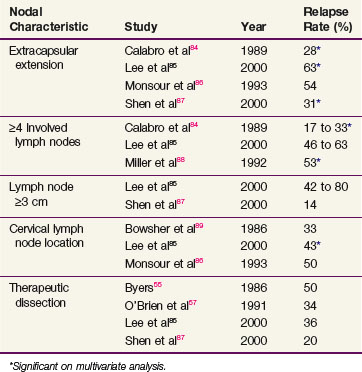

For most patients, nodal dissection results in more than an 80% likelihood of regional control. For patients with certain clinicopathologic features, however, the surgical literature suggests regional recurrence rates as high as 80% and, therefore, a need for additional regional therapy. Although nodal extracapsular extension remains the strongest predictor of subsequent regional recurrence after surgery alone, several series have reported elevated recurrence rates if at least four lymph nodes are involved, the lymph nodes measure at least 3 cm in diameter, they are located in the cervical basin, or they are detected during a therapeutic dissection (as opposed to elective dissection or at the time of sentinel lymph node biopsy).84,85,86–89 Although less well described in the literature, nodal recurrence after previous dissection for involved regional nodes also places the patient at increased risk of subsequent relapse. Patients with one of these six clinicopathologic features have a 30% to 50% rate of subsequent regional recurrence after nodal dissection alone (Table 40-6).

TABLE 40-6 Regional Relapse Rates after Surgery Alone for Nodal Disease According to High-Risk Pathologic Characteristics

There are substantial data supporting the effectiveness of regional irradiation for patients with one of the aforementioned high-risk features. Relapse rates after adjuvant irradiation range from 5% to 20%, compared with the much higher range seen without adjuvant irradiation* (compare Tables 40-6 and 40-7). The Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group and the Australia and New Zealand Melanoma Trials group completed a randomized trial comparing nodal observation with radiation therapy after lymphadenectomy in patients with palpable nodal disease and one of the high-risk features.101 Although there was no improvement in OS, this trial reports an acceptable acute toxicity and 2-year regional control of 80% with radiation therapy compared with 68% without it (p = .041).

TABLE 40-7 Regional Relapse Rates after Surgery and Radiotherapy for Regionally Advanced Nodal Disease

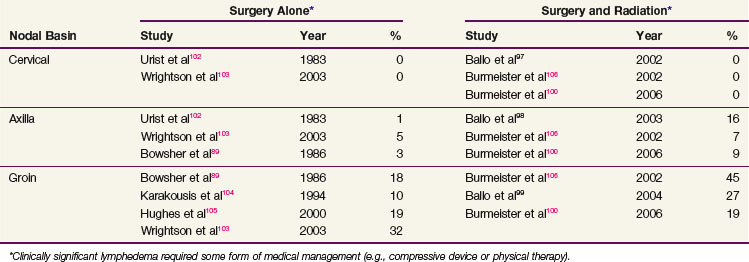

Tolerance to adjuvant radiation therapy is generally excellent. Most patients receiving comprehensive neck irradiation experience transient parotid swelling after the first radiation fraction that typically lasts 1 day. For most sites, brisk erythema with patches of moist skin desquamation, particularly within the axilla and the groin, are common. Late radiation-related complications are distinctly uncommon, except for thinning of the subcutaneous fat with mild or moderate fibrosis. Clinically significant extremity lymphedema (requiring some form of medical management such as a compressive sleeve or physical therapy) occurs in a minority of patients, but it can be problematic. It is more common after groin dissection than after cervical or axillary dissection, and it appears to moderately increase further in the setting of adjuvant irradiation, particularly for patients with locally advanced groin metastases89,97–99,100–106 (Table 40-8). In one series examining the timing of lymphedema, however, half of the patients had developed lymphedema before starting adjuvant groin irradiation.99 This suggested that the higher rate of lymphedema was to some extent a consequence of locally advanced disease and its surgical treatment and not due solely to the irradiation. In this same series, there was a correlation between body mass index and the development of chronic lymphedema, suggesting that patient factors need to be incorporated into rational treatment guidelines.99

Distant Disease and Adjuvant Systemic Therapy

A great amount of resources has been directed toward developing effective systemic therapy for patients with melanoma. Although surgical resection with selective use of adjuvant irradiation results in satisfactory local and regional control for most patients, even thin melanomas have significant metastatic potential. Most research initiatives have focused on interferon alpha-2b (IFN) or vaccines, or combinations of both. European investigators have examined the role of low-dose IFN therapy, and U.S. investigators have focused primarily on high-dose regimens. Three randomized Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) trials support the use of adjuvant IFN for patients with stage T4 primary disease and those with nodal metastases from melanoma.107,108,109

The first trial (ECOG 1684) enrolled 287 patients with primary melanomas thicker than 4 mm without palpable nodes, lymph node metastasis detected at elective lymph node dissection, a clinically palpable regional lymph node with primary melanoma of any stage, or regional lymph node recurrence at any interval after appropriate surgery for primary melanoma of any depth.107 This prospective study revealed a significant prolongation of relapse-free survival (RFS) (5-year actuarial, 37% vs. 26%; p = .002) and OS (5-year, 46% vs. 37%; p = .02) associated with high-dose IFN therapy (i.e., intravenous administration five times per week for 4 weeks, then subcutaneous administration three times per week for 48 weeks). The overall benefit of treatment in this trial was correlated with the tumor burden and the presence of microscopic nonpalpable and palpable regional lymph node metastases. The benefit of therapy with IFN was greatest among recipients with palpable regional nodal metastases or nodal recurrences.

The second trial (ECOG 1690) compared high-dose IFN for 1 year or low-dose IFN for 2 years versus observation.108 Intent-to-treat analysis revealed 5-year RFS of 44% and 40% for the high-dose and low-dose IFN arms, respectively, compared with 35% in the observation arm (p = .05 for high-dose IFN vs. observation, and p = .17 for low-dose IFN vs. observation). Most of the benefit was observed for patients with two to three involved lymph nodes. For OS, there was no difference demonstrated for the three treatment arms (52%, 53%, and 55% for high-dose IFN, low-dose IFN, and observation, respectively).

The third trial (ECOG 1694) compared high-dose IFN with a ganglioside GM2 melanoma vaccine.109 After 880 patients were randomized to one of the treatment arms, an interim analysis indicated inferiority of the ganglioside vaccine with respect to RFS and OS. In a subgroup analysis, however, the beneficial effects of IFN were seen only in the patients with stage T4N0 disease and not those with nodal disease.

Debate over the merits of routine IFN therapy has focused on the inconsistent subgroup analysis findings and concerns about the toxicity of IFN.110 In ECOG trials 1684 and 1690, the node-positive patients benefited most from adjuvant IFN, whereas only the node-negative patients benefited in ECOG trial 1694. Advocates of IFN argue that the subgroups analyzed in the individual trials were too small to detect real differences in survival and that the relative benefits of interferon are consistent across all subgroups of patients. IFN toxicity was evaluated using a survival analysis adjusted for quality of life.111 This determined that although the high-dose IFN group was essentially trading 8.9 months of time without disease relapse for 5.8 months of severe IFN-related toxicity, the time without disease relapse was valued more than the time with toxicity.

Frequently observed regression of primary melanoma and even occasionally metastatic disease has suggested an important role for the immune system. This has fueled a long-standing search for active vaccine therapies against melanoma, which have included whole-cell, dendritic cell, peptide, ganglioside, and DNA vaccines as well as viral vectors.112 To date, none of these approaches has demonstrated clinical efficacy in terms of OS or been granted approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in melanoma patients.113

Irradiation Techniques

Target Volume

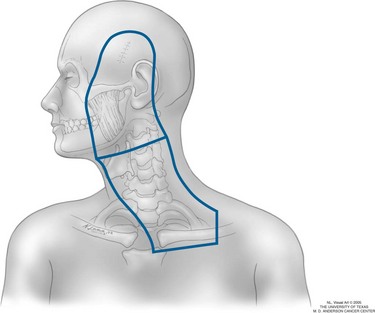

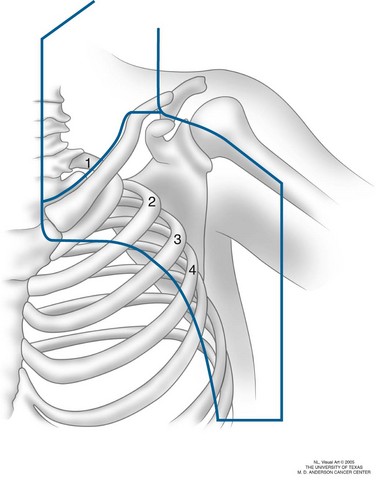

The target volume for patients receiving elective nodal irradiation for head and neck primary sites includes the primary lesion, the preauricular and postauricular lymph nodes (for high facial and scalp primary tumors), and the ipsilateral lymph nodes from levels I through V, including the ipsilateral supraclavicular fossa (Fig. 40-3). For patients receiving therapeutic nodal irradiation for one of the aforementioned high-risk nodal features, the target volume is essentially the same, except that the primary tumor bed is irradiated only if regional relapse occurred less than 1 year after excision of the primary disease.

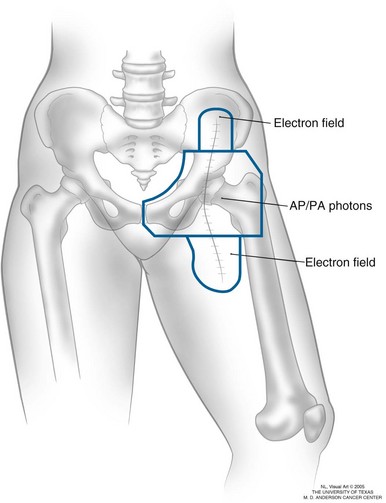

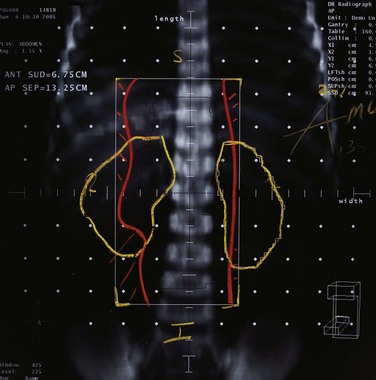

For axillary nodal metastases, radiation fields include the axillary lymph nodes from levels I through III (Fig. 40-4). The supraclavicular fossa and low cervical lymph nodes may be included if there is bulky high axillary disease.

At a minimum, fields for groin lymph node metastases cover the nodal regions that have pathologically confirmed nodal disease and always include the entire surgical scar (Fig. 40-5). Judgment must be used regarding elective irradiation of adjacent nodal regions (i.e., external iliac coverage in the setting of confirmed inguinal disease) because of concern about the increased toxicity associated with groin irradiation, particularly for obese patients. Unlike the cervical or axillary regions, where electrons and flashing photon fields, respectively, generally deliver a full dose to the skin, special attention must be paid to delivering a full dose to the groin scar.

Setup, Field Arrangement, and Dose-Fractionation Schedule

For all sites of regional disease, an alternative fractionation schedule is 48 Gy in 20 daily fractions, based upon the results of the Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group and the Australia and New Zealand Melanoma Trials group randomized trial.101

Treatment Algorithms and Clinical Trials

Therapeutic Nodal Approaches

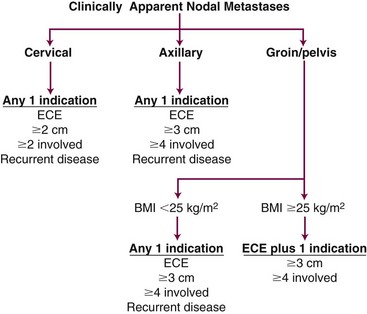

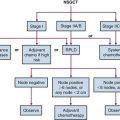

Therapeutic nodal dissection is the standard treatment for patients with lymph node metastases, and available data support the use of systemic, high-dose adjuvant IFN. Adjuvant postoperative irradiation is also indicated to reduce the regional recurrence rate in patients with high-risk clinicopathologic features. Although some of the same features that predict regional failure, such as extracapsular extension and number of involved lymph nodes, also predict distant failure, the importance of regional control should not be underestimated, and irradiation should not be systematically avoided, because the risk of distant metastasis is perceived to be too high. At the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, we have developed radiation treatment guidelines that account for the complex clinical interaction between the risk of regional recurrence, the risk of regional toxicity, and the risk of distant metastatic disease (Fig. 40-6). For patients with cervical disease, the threshold for irradiation may be lowered to include those with at least two involved lymph nodes or those with tumors measuring at least 2 cm in diameter. For patients with groin metastases, the threshold may be raised so that combinations (two or more) of the high-risk features must be present before adjuvant irradiation is given.

1 Sause WT, Cooper JS, Rush S, et al. Fraction size in external beam radiation therapy in the treatment of melanoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1986;12:1839-1842.

2 Ballo MT, Ang KK. Radiation therapy for malignant melanoma. Surg Clin North Am. 2003;83:323-342.

3 Chang DT, Amdu RJ, Morris CG, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy for cutaneous melanoma. Comparing hypofractionation to conventional fractionation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:1051-1055.

8 Tucker MA, Goldstein AM. Melanoma etiology. Where are we? Oncogene. 2003;22:3042-3052.

13 Hill L, Ferrini RL. Skin cancer prevention and screening. Summary of the American College of Preventive Medicine’s practice policy statements. CA Cancer J Clin. 1998;48:232-235.

27 Balch CM, Soong S, Gershenwald JE, et al. Prognostic factors analysis of 17,600 melanoma patients. Validation of the American Joint Committee on Cancer melanoma staging system. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3622-3634.

34 Thomas JM, Newton-Bishop J, A’Hern R, et al. Excision margins in high-risk malignant melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:757-766.

45 Vuylsteke RJ, van Leeuwen PA, Statius Muller MG, et al. Clinical outcome of stage I/II melanoma patients after selective sentinel lymph node dissection. Long-term follow up results. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1057-1065.

46 McMasters KM, Wong SL, Edwards MJ, et al. Factors that predict the presence of sentinel lymph node metastasis in patients with melanoma. Surgery. 2001;130:151-156.

67 Vongtama R, Safa A, Gallardo D, et al. Efficacy of radiation therapy in the local control of desmoplastic malignant melanoma. Head Neck. 2003;25:423-428.

76 Balch CM, Soong S, Ross MI, et al. Long-term results of a multi-institutional randomized trial comparing prognostic factors and surgical results for intermediate thickness melanomas (1.0-4.0 mm). Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:87-97.

77 Cascinelli N, Morabito A, Santinami M, et al. Immediate or delayed dissection of regional nodes in patients with melanoma of the trunk. A randomised trial. Lancet. 1998;351:793-796.

79 McMasters KM. What good is sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma if it does not improve survival? Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:810-812.

80 Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al. Sentinel–node biopsy or nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1307-1317.

81 Thomas JM, A’Hern RP, Grichnik JM, et al. Sentinel-node biopsy in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:418.

83 Bonnen MD, Ballo MT, Myers JN, et al. Elective radiotherapy provides regional control for patients with cutaneous melanoma of the head and neck. Cancer. 2003;100:383-389.

85 Lee RJ, Gibbs JF, Proulx GM, et al. Nodal basin recurrence following lymph node dissection for melanoma. Implications for adjuvant radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;46:467-474.

97 Ballo MT, Strom EA, Zagars GK, et al. Adjuvant irradiation for axillary metastases from malignant melanoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52:964-972.

98 Ballo MT, Bonnen MD, Garden AS, et al. Adjuvant irradiation for cervical lymph node metastases from melanoma. Cancer. 2003;97:1789-1796.

99 Ballo MT, Zagars GK, Gershenwald JE, et al. A critical assessment of adjuvant radiotherapy for inguinal lymph node metastases from melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:1079-1084.

108 Kirkwood JM, Ibrahim JG, Sondak VK, et al. High- and low-dose interferon alpha-2b in high-risk melanoma. First analysis of intergroup trial E1690/s9111/c9190. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2444-2458.

110 Sabel MS, Sondak VK. Pros and cons of adjuvant interferon in the treatment of melanoma. Oncologist. 2003;8:451-458.

111 Cole BF, Gelber RD, Kirkwood JM, et al. Quality-of-life-adjusted survival analysis of interferon alpha-2b adjuvant treatment of high-risk resected cutaneous melanoma. An Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2666-2673.

1 Sause WT, Cooper JS, Rush S, et al. Fraction size in external beam radiation therapy in the treatment of melanoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1986;12:1839-1842.

2 Ballo MT, Ang KK. Radiation therapy for malignant melanoma. Surg Clin North Am. 2003;83:323-342.

3 Chang DT, Amdu RJ, Morris CG, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy for cutaneous melanoma. Comparing hypofractionation to conventional fractionation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:1051-1055.

4 Jemal A, Siegal R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(5):277-300.

5 Beral V, Evans S, Shaw H, et al. Cutaneous factors related to the risk of malignant melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 1983;109:165-172.

6 Gellin GA, Kopf AW, Garfinkel L. Malignant melanoma. A controlled study of possibly associated factors. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:43-48.

7 English DR, Armstrong BK, Kricker A, et al. Sunlight and cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 1997;8:271-283.

8 Tucker MA, Goldstein AM. Melanoma etiology. Where are we? Oncogene. 2003;22:3042-3052.

9 Hussussian CJ, Struewing JP, Goldstein AM, et al. Germline p16 mutations in familial melanoma. Nat Genet. 1994;8:15-21.

10 Aitken J, Welch J, Duffy D, et al. CDKN2A variants in a population-based sample of Queensland families with melanoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;3:446-452.

11 Bishop DT, Demanais F, Goldstein AM, et al. Geographical variation in the penetrance of CDKN2A mutation in melanoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:894-903.

12 Bliss JM, Ford D, Swerdlow AJ, et al. Risk of cutaneous melanoma associated with pigmentation characteristics and freckling. Systematic overview of 10 case controlled studies. The International Melanoma Analysis Group (IMAGE). Int J Cancer. 1995;62:367-376.

13 Hill L, Ferrini RL. Skin cancer prevention and screening. Summary of the American College of Preventive Medicine’s practice policy statements. CA Cancer J Clin. 1998;48:232-235.

14 Gruber SB, Barnhill RL, Stenn KS, et al. Nevomelanocytic proliferations in association with cutaneous melanoma. A multivariate analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:773-780.

15 Clark WH, Ainsworth AM, Bernardino EA. The developmental biology of primary human malignant melanomas. Semin Oncol. 1975;2:83-103.

16 McGovern VJ, Murad TM. Pathology of melanoma: An overview. In: Balch CM, Milton GW, editors. Cutaneous Melanoma: Clinical Management and Treatment Results Worldwide. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1985:29-53.

17 Barnhill RL, Mihm MC. Histopathology of malignant melanoma and its precursor lesions. In: Balch CM, Houghton AN, Milton GW, et al, editors. Cutaneous Melanoma. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1992:234-263.

18 Urist MM, Balch CM, Soong SJ. Head and neck melanoma in 534 clinical stage I patients. A prognostic factor analysis and results of surgical treatment. Ann Surg. 1984;200:769-775.

19 Clark WH, Mihm MC. Lentigo maligna and lentigo-maligna melanoma. Am J Pathol. 1969;55:39-67.

20 Reed RJ. The pathology of human cutaneous melanoma. In: Malignant melanoma I. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff; 1983:85-116.

21 Arrington JH, Reed RJ, Ichinose H, et al. Plantar lentiginous melanoma. A distinctive variant of human cutaneous malignant melanoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1977;1:131-143.

22 Coleman WP, Loria PR, Reed RJ, et al. Acral lentiginous melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:773-776.

23 Krementz ET, Feed RJ, Coleman WP, et al. Acral lentiginous melanoma. A clinicopathologic entity. Ann Surg. 1982;195:632-645.

24 Seiji M, Takahashi M. Acral melanoma in Japan. Hum Pathol. 1982;13:607-609.

25 Reintgen DS, McCarty KM, Cox E, et al. Malignant melanoma in black American and white American populations. A comparative review. JAMA. 1982;248:1856-1859.

26 Breslow A. Thickness, cross-sectional areas and depth of invasion in the prognosis of cutaneous melanoma. Ann Surg. 1970;172:902-908.

27 Balch CM, Soong S, Gershenwald JE, et al. Prognostic factors analysis of 17,600 melanoma patients. Validation of the American Joint Committee on Cancer melanoma staging system. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3622-3634.

28 Balch CM, Buzaid AC, Soong S, et al. Final version of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3635-3648.

29 Buzaid AC, Tinoco L, Ross MI, et al. Role of computed tomography in the staging of patients with local-regional metastases of melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2104-2108.

30 Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Adamus J, et al. Thin stage I primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. Comparison of excision with margins of 1 or 3 cm [Erratum: N Engl J Med 325:292, 1991]. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:1159-1162.

31 Cohn-Cedermark G, Rutqvist LE, Andersson R, et al. Long term results of a randomized study by the Swedish Melanoma Study Group on 2-cm versus 5-cm resection margins for patients with cutaneous melanoma with a tumor thickness of 0.8-2.0 mm. Cancer. 2000;89:1495-1501.

32 Balch CM, Soong S, Smith T, et al. Long-term results of a prospective surgical trial comparing 2 cm versus 4 cm excision margins for 740 patients with 1-4 mm melanomas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:101-108.

33 Khayat D, Rixe O, Martin G, et al. Surgical margins in cutaneous melanoma (2 cm versus 5 cm) for lesions measuring less than 2.1-mm thick. Long-term results of a large European multicentric phase III study. Cancer. 2003;97:1941-1946.

34 Thomas JM, Newton-Bishop J, A’Hern R, et al. Excision margins in high-risk malignant melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:757-766.

35 Heaton KM, Sussman JJ, Gershenwald JE, et al. Surgical margins and prognostic factors in patients with thick (>4 mm) primary melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 1998;5:322-328.

36 Krag DN, Meijer SJ, Weaver DL, et al. Minimal-access surgery for staging of malignant melanoma. Arch Surg. 1995;130:654-658.

37 Joseph E, Brobeil A, Glass F, et al. Results of complete lymph node dissection in 83 melanoma patients with positive sentinel nodes. Ann Surg Oncol. 1998;5:119-125.

38 Mraz-Gernhard S, Sagebiel RW, Kashani-Sabet M, et al. Prediction of sentinel lymph node micrometastasis by histological features in primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:983-987.

39 Haddad FF, Stall A, Messina J, et al. The progression of melanoma nodal metastasis is dependent on tumor thickness of the primary lesion. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999;6:144-149.

40 Gershenwald JE, Thompson W, Mansfield PF, et al. Multi-institutional melanoma lymphatic mapping experience. The prognostic value of sentinel lymph node status in 612 stage I and II melanoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:976-983.

41 Statius Muller MG, Borgstein PJ, Pijpers R, et al. Reliability of the sentinel node procedure in melanoma patients. Analysis of failures after long-term follow-up. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:461-468.

42 Bachter D, Michl C, Büchels H, et al. The predictive value of the sentinel lymph node in malignant melanomas. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2001;58:129-136.

43 Blumenthal R, Banic A, Brand CU, et al. Morbidity and outcome after sentinel lymph node dissection in patients with early-stage malignant cutaneous melanoma. Swiss Surg. 2002;8:209-214.

44 Caprio MG, Carbone G, Bracigliano A, et al. Sentinel lymph node detection by lymphoscintigraphy in malignant melanoma. Tumori. 2002;88:S43-S45.

45 Vuylsteke RJ, van Leeuwen PA, Statius Muller MG, et al. Clinical outcome of stage I/II melanoma patients after selective sentinel lymph node dissection. Long-term follow up results. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1057-1065.

46 McMasters KM, Wong SL, Edwards MJ, et al. Factors that predict the presence of sentinel lymph node metastasis in patients with melanoma. Surgery. 2001;130:151-156.

47 Rousseau DL, Ross MI, Johnson MM, et al. Revised American Joint Committee on Cancer staging criteria accurately predict sentinel lymph node positivity in clinically node-negative melanoma patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:569-574.

48 Harwood AR. Conventional fractionated radiotherapy for 51 patients with lentigo maligna and lentigo maligna melanoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1983;9:1019-1021.

49 Urist MM, Balch CM, Soong S, et al. The influence of surgical margins and prognostic factors predicting the risk of local recurrence in 3445 patients with primary cutaneous melanoma. Cancer. 1985;55:1398-1402.

50 Ames FC, Balch CM, Reintgen D. Local recurrence and their management. In: Balch CM, Houghton AN, Milton GW, et al, editors. Cutaneous Melanoma. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1992:287-294.

51 Roses DF, Harris MN, Rigel D, et al. Local and in-transit metastases following definitive excision for primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. Ann Surg. 1983;198:65-69.

52 Karakousis CP, Balch CM, Urist MM, et al. Local recurrence in malignant melanoma. Long-term results of the multiinstitutional randomized surgical trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 1996;3:446-452.

53 Ng AK, Jones WO, Shaw JH. Analysis of local recurrence and optimizing excision margins for cutaneous melanoma. Br J Surg. 2001;88:137-142.

54 Neades GT, Orr DJ, Hughes LE, et al. Safe margins in the excision of primary cutaneous melanoma. Br J Surg. 1993;80:731-733.

55 Byers RM. The role of modified neck dissection in the treatment of cutaneous melanoma of the head and neck. Arch Surg. 1986;121:1338-1341.

56 Loree TR, Spiro RH. Cutaneous melanoma of the head and neck. Am J Surg. 1989;158:388-391.

57 O’Brien CJ, Coates AS, Petersen-Schaefer K, et al. Experience with 998 cutaneous melanomas of the head and neck over 30 years. Am J Surg. 1991;162:310-314.

58 Fisher SR, O’Brien CJ. Head and neck melanoma. In: Balch CM, Houghton AN, Sober AJ, Soong S, editors. Cutaneous Melanoma. St Louis: Quality Medical Publishing; 1998:163-174.

59 Kelly JW, Sagebiel RW, Calderon W, et al. The frequency of local recurrence and microsatellites as a guide to reexcision margins for cutaneous malignant melanoma. Ann Surg. 1984;200:759-763.

60 Leon P, Daly JM, Synnestvedt M, et al. The prognostic implications of microscopic satellites in patients with clinical stage I melanoma. Arch Surg. 1991;126:1461-1468.

61 Egbert B, Kempson R, Sagebiel R. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma. A clinicohistopathologic study of 25 cases. Cancer. 1988;62:2033-2041.

62 Beenken S, Byers R, Smith JL, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989;115:374-379.

63 Smithers BM, McLeod GR, Little JH. Desmoplastic melanoma. Patterns of recurrence. World J Surg. 1992;16:186-190.

64 Calson JA, Dickersin GR, Sober AJ, et al. Desmoplastic neurotropic melanoma. A clinicopathologic analysis of 28 cases. Cancer. 1995;75:478-494.

65 Quinn MJ, Crotty KA, Thompson JF, et al. Desmoplastic and desmoplastic neurotropic melanoma. Experience with 280 patients. Cancer. 1998;83:1128-1135.

66 Payne WG, Kearney R, Wells K, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma. Am Surg. 2001;67:1004-1006.

67 Vongtama R, Safa A, Gallardo D, et al. Efficacy of radiation therapy in the local control of desmoplastic malignant melanoma. Head Neck. 2003;25:423-428.

68 Jaroszewski DE, Pockaj BA, DiCaudo DJ, et al. The clinical behavior of desmoplastic melanoma. Am J Surg. 2001;182:590-595.

69 Arora A, Lowe L, Su L, et al. Wide excision without radiation for desmoplastic melanoma. Cancer. 2005;104:1462-1467.

70 Chen JY, Hruby G, Scolyer RA, et al. Desmoplastic neurotropic melanoma. A clinicopathologic analysis of 128 cases. Cancer. 2008;113:2770-2778.

71 Pawlik TM, Ross MI, Prieto VG, et al. Assessment of the role of sentinel lymph node biopsy for primary cutaneous desmoplastic melanoma. Cancer. 2006;106:900-906.

72 Posther KE, Selim MA, Mosca PJ, et al. Histopathologic characteristics, recurrence patterns and survival of 129 patients with desmoplastic melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:728-739.

73 Milton GW, Shaw HM, McCarthy WH, et al. Prophylactic lymph node dissection in clinical stage I cutaneous malignant melanoma. Results of surgical treatment in 1319 patients. Br J Surg. 1982;69:108-111.

74 Veronesi U, Adamus J, Bandiera DC, et al. Delayed regional lymph node dissection in stage I melanoma of the skin of the lower extremities. Cancer. 1982;49:2420-2430.

75 Sim FH, Taylor WF, Pritchard DJ, et al. Lymphadenectomy in the management of stage I malignant melanoma. A prospective randomized study. Mayo Clin Proc. 1986;61:697-705.

76 Balch CM, Soong S, Ross MI, et al. Long-term results of a multi-institutional randomized trial comparing prognostic factors and surgical results for intermediate thickness melanomas (1.0-4.0 mm). Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:87-97.

77 Cascinelli N, Morabito A, Santinami M, et al. Immediate or delayed dissection of regional nodes in patients with melanoma of the trunk. A randomised trial. Lancet. 1998;351:793-796.

78 Doubrovsky A, de Wilt JH, Scolyer RA, et al. Sentinel node biopsy provides more accurate staging than elective lymph node dissection in patients with cutaneous melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:829-836.

79 McMasters KM. What good is sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma if it does not improve survival? Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:810-812.

80 Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al. Sentinel–node biopsy or nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1307-1317.

81 Thomas JM, A’Hern RP, Grichnik JM, et al. Sentinel-node biopsy in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:418.

82 Ang KK, Peters LJ, Weber RS, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy for cutaneous melanoma of the head and neck region. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1994;30:795-798.

83 Bonnen MD, Ballo MT, Myers JN, et al. Elective radiotherapy provides regional control for patients with cutaneous melanoma of the head and neck. Cancer. 2003;100:383-389.

84 Calabro A, Singletary SE, Balch CM. Patterns of relapse in 1001 consecutive patients with melanoma nodal metastases. Arch Surg. 1989;124:1051-1055.

85 Lee RJ, Gibbs JF, Proulx GM, et al. Nodal basin recurrence following lymph node dissection for melanoma. Implications for adjuvant radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;46:467-474.

86 Monsour PD, Sause WT, Avent JM, et al. Local control following therapeutic nodal dissection for melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 1993;54:18-22.

87 Shen P, Wanek LA, Morton DL. Is adjuvant radiotherapy necessary after positive lymph node dissection in head and neck melanomas? Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:554-559.

88 Miller EJ, Synnestvedt M, Schultz D, et al. Loco-regional nodal relapse in melanoma. Surg Oncol. 1992;1:333-340.

89 Bowsher WG, Taylor BA, Hughes LE. Morbidity, mortality and local recurrence following regional node dissection for melanoma. Br J Surg. 1986;73:906-908.

90 Burmeister BH, Smithers BM, Poulsen M, et al. Radiation therapy for nodal disease in malignant melanoma. World J Surg. 1995;19:369-371.

91 O’Brien CJ, Petersen-Schaefer K, Stevens GN, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy following neck dissection and parotidectomy for metastatic malignant melanoma. Head Neck. 1997;19:589-594.

92 Corry J, Smith JG, Bishop M, et al. Nodal radiation therapy for metastatic melanoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;44:1065-1069.

93 Fenig E, Eidelevich E, Njuguna E, et al. Role of radiation therapy in the management of cutaneous malignant melanoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 1999;22:184-186.

94 Morris KT, Marquez CM, Holland JM, et al. Prevention of local recurrence after surgical debulking of nodal and subcutaneous melanoma deposits by hypofractionated radiation. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:680-684.

95 Cooper JS, Chang WS, Oratz R, et al. Elective radiation therapy for high-risk malignant melanoma. Cancer J. 2001;7:498-502.

96 Fuhrmann D, Lippold A, Borrosch F, et al. Should adjuvant radiotherapy be recommended following resection of regional lymph node metastases of malignant melanomas? Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:66-70.

97 Ballo MT, Strom EA, Zagars GK, et al. Adjuvant irradiation for axillary metastases from malignant melanoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52:964-972.

98 Ballo MT, Bonnen MD, Garden AS, et al. Adjuvant irradiation for cervical lymph node metastases from melanoma. Cancer. 2003;97:1789-1796.

99 Ballo MT, Zagars GK, Gershenwald JE, et al. A critical assessment of adjuvant radiotherapy for inguinal lymph node metastases from melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:1079-1084.

100 Burmeister BH, Smithers M, Burmeister E, et al. A prospective phase II study of adjuvant postoperative radiation therapy following nodal surgery in malignant melanoma. Trans Tasman Radiation Oncology Group (TROG) study 96.06. Radiother Oncol. 2006;81:136-142.

101 Burmeister B, Henderson M, Thompson J, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy improves regional (lymph node field) control in melanoma patients after lymphadenectomy. Results of an intergroup randomized trial (TROG 02.01/ANZMTG 01.02). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75(Suppl 1):S2. (Abstract 3)

102 Urist MM, Maddox WA, Kennedy JE, et al. Patient risk factors and surgical morbidity after regional lymphadenectomy in 204 melanoma patients. Cancer. 1983;51:2152-2156.

103 Wrightson WR, Wong SL, Edwards MJ, et al. Complications associated with sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:676-680.

104 Karakousis CP, Driscoll DL, Rose B, et al. Groin dissection in malignant melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 1994;1:271-277.

105 Hughes TM, A’Hern RP, Thomas JM. Prognosis and surgical management of patients with palpable inguinal lymph node metastases from melanoma. Br J Surg. 2000;87:892-901.

106 Burmeister BH, Smithers BM, Davis S, et al. Radiation following nodal surgery for melanoma. An analysis of late toxicity. ANZ J Surg. 2002;72:344-348.

107 Kirkwood JM, Strawderman MH, Ernstoff MS, et al. Interferon alfa-2b adjuvant therapy of high-risk resected cutaneous melanoma. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial EST 1684. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:7-17.

108 Kirkwood JM, Ibrahim JG, Sondak VK, et al. High- and low-dose interferon alpha-2b in high-risk melanoma. First analysis of intergroup trial E1690/s9111/c9190. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2444-2458.

109 Kirkwood JM, Ibrahim JG, Sosman JA, et al. High-dose interferon alpha-2b significantly prolongs relapse-free and overall survival compared with the GM2-KLH/QS-21 vaccine in patients with resected stage IIB-III melanoma. Results of intergroup trial E1694/S9512/C509801. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2370-2380.

110 Sabel MS, Sondak VK. Pros and cons of adjuvant interferon in the treatment of melanoma. Oncologist. 2003;8:451-458.

111 Cole BF, Gelber RD, Kirkwood JM, et al. Quality-of-life-adjusted survival analysis of interferon alpha-2b adjuvant treatment of high-risk resected cutaneous melanoma. An Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2666-2673.

112 Lens M. The role of vaccine therapy in the treatment of melanoma. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2008;8:315-323.

113 Morton DL, Faries MB. Therapeutic vaccines for melanoma. Current status. Biodrugs. 2005;19:247-260.