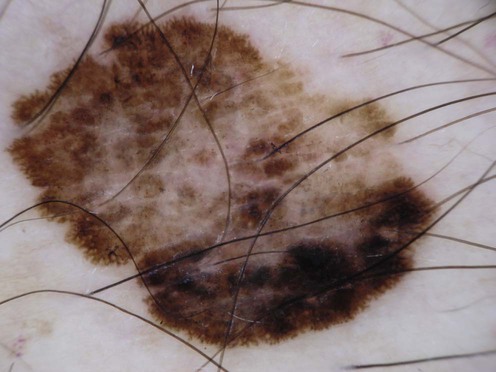

Malignant melanoma

Management strategy

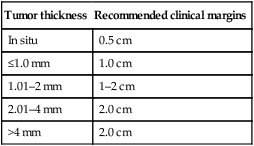

Staging of melanoma is crucial because it not only assigns patients into well-defined risk groups, it also aids in clinical decision-making as reviewed in the latest National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) clinical practice guidelines on melanoma. The goal of surgical management of primary cutaneous melanoma is to achieve negative histological margins to prevent recurrence and metastases. The current surgical margin guidelines from the NCCN are based on Breslow depth (Table 143.1). The standard treatment for stage IA melanoma is wide local excision. Total excision of primary melanoma with wide margins offers the best chance for cure. However, melanoma cells may extend non-contiguously for several millimeters beyond the visible lesion.

Table 143.1

Current melanoma excisional margin guidelines

| Tumor thickness | Recommended clinical margins |

| In situ | 0.5 cm |

| ≤1.0 mm | 1.0 cm |

| 1.01–2 mm | 1–2 cm |

| 2.01–4 mm | 2.0 cm |

| >4 mm | 2.0 cm |

Specific investigations

First-line therapies

Second-line therapies

Surgical excision

Surgical excision Selective lymphadenectomy

Selective lymphadenectomy Elective lymphadenectomy

Elective lymphadenectomy Pegylated interferon alfa-2b

Pegylated interferon alfa-2b Paclitaxel and carboplatin

Paclitaxel and carboplatin Imiquimod

Imiquimod Interleukin-2

Interleukin-2 Isolated limb perfusion

Isolated limb perfusion Bcl-2 antisense and dacarbazine

Bcl-2 antisense and dacarbazine Dacarbazine

Dacarbazine Dacarbazine

Dacarbazine Vemurafenib

Vemurafenib Trametinib

Trametinib Imatinib

Imatinib Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy Mohs micrographic surgery

Mohs micrographic surgery