CHAPTER 41 Malignant disease of the vulva and vagina

Introduction

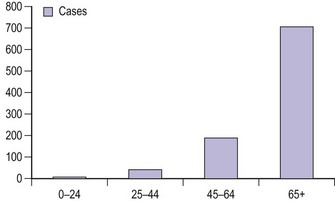

Vulval cancer is an uncommon condition that largely affects elderly women (Figure 41.1). The Office of National Statistics recorded 842 cases in 2005 (Office of National Statistics 2008). This incidence of 3.3 per 100,000 ranks vulvar cancer as the 20th most common cancer in women. The most recent mortality figures recorded 270 deaths for all age groups, giving a death rate of 1.05 per 100,000 women (0.53/105 persons), ranking it the 19th most common cause of cancer death in women.

Aetiology

There seem to be two distinct types of vulval carcinoma: the first type occurs predominantly in older women, is typically a well-differentiated keratinizing tumour that is not associated with usual-type vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) or human papilloma virus (HPV) infection, but which often shows adjacent epithelial disorders such as lichen sclerosus and/or differentiated VIN; and a second type which mainly occurs in younger women, is associated with usual-type VIN, shows evidence of oncogenic HPV infection, and may be associated with synchronous or metachronous squamous preneoplastic or neoplastic lesions of the cervix, vagina and anal canal (Crum et al 1997, van der Avoort et al 2006). Smoking may be an important cofactor involved in the aetiology of HPV-related vulvar tumours (Hussain et al 2008).

The following are recognized risk factors for all types of vulval cancer:

Histology

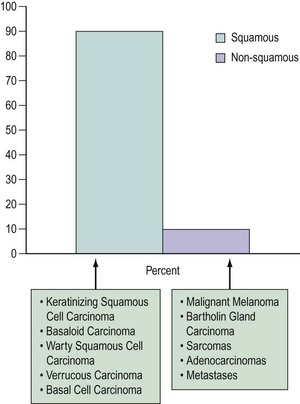

The majority of vulvar cancers (90%) are squamous in origin (Figure 41.2). Verrucous and basal cell cancers are squamous cell variants.

Non-squamous cancers include Bartholin’s gland cancer and other adenocarcinomas, malignant melanoma, Paget’s disease and sarcomas. The vulva may also be a site for lymphoma and metastases from elsewhere (Finan 2003). Rarely, primary breast cancers have been reported (Piura et al 2002).

Lymphatic Drainage

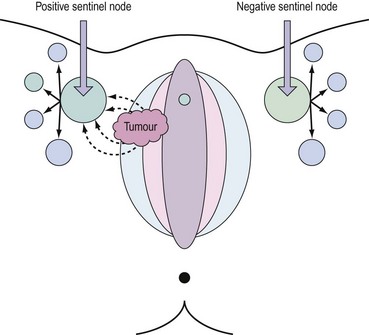

Lymph drains from the vulva to the superficial inguinal glands and then to the deep femoral glands in the groin. Drainage continues to the external iliac glands. Drainage to both groins occurs from midline structures — the perineum and the clitoris — but some contralateral spread may take place from other parts of the vulva (Iversen and Aas 1983). Direct spread to the pelvic nodes along the internal pudendal vessels occurs very rarely, and no direct pathway from the clitoris to the pelvic nodes has been demonstrated consistently. An important aspect of the lymphatic drainage is the concept of sentinel nodes in each groin. This is the first node that draining lymph encounters as it drains bilaterally from the vulvar basin (Cabanas 1977). This anatomical concept has been exploited recently to develop selective lymphadenectomy in this disease.

Natural History of Squamous Cancers

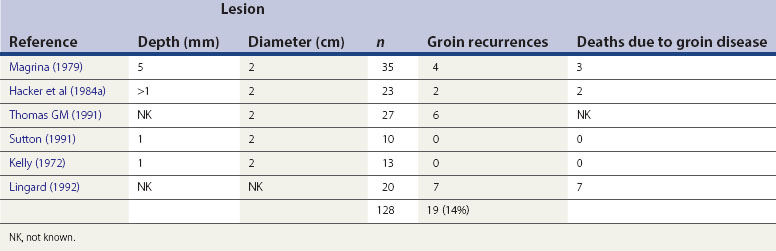

Malignant transformation may occur in more than one site, and this appears to apply in both HPV-negative and -positive scenarios, although more commonly in the latter. The earliest recognizable phase of vulval cancer is termed ‘superficially invasive disease’ (stage Ia). The tumour is less than 2 cm in lateral dimension, and there is less than 1 mm invasion when measured from the base of an adjacent dermal papilla. Accurate identification and classification of this stage requires expert pathological interpretation, and is exceptionally important as the current consensus would suggest a virtually negligible risk of lymph node metastases. As the cancer gradually increases in size and progressively invades the deeper layers of the dermis, it spreads locally. The tumour will eventually involve the local lymphatics, hence the propensity for groin lymph node involvement (Table 41.1).

Presentation

The medial aspects of the labia majora are the most common sites for disease to develop (70%). The labia minora, clitoris, periurethral areas, posterior fourchette and perineum account for the remainder (30%). Small lesions may be asymptomatic and go unnoticed by the patient. However, both Hacker et al (1981) and Monaghan (1990) have commented that, in a significant minority of patients, there appears to be considerable delay in presentation. The intimate nature of the disease, fear and/or ignorance and the advanced age of many patients might partly explain this observation. The fact that the disease is uncommon may also be contributory, as primary carers may not recognize the significance of symptoms or fail to recognize the clinical signs. Whatever the cause, a significant number of cases continue to present in advanced stages.

The reasons for presenting have been analysed by Podratz et al (1983a). Pruritus is the most common presenting symptom (71%), and an ulcer or mass will have been noted in nearly 80% of cases. Surprisingly, pain is only a feature in 23% of cases. Bleeding (26%), discharge (13%) and urinary tract dysfunction (14%) are other common reasons for presentation.

Examination

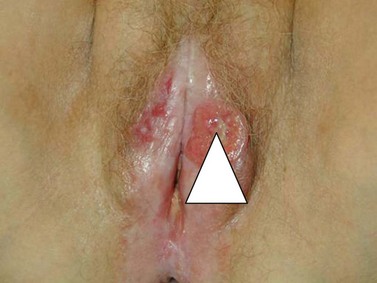

The character, size and location(s) of all lesions should be documented. Particular attention should be paid to assess any involvement of the vagina, urethra, bladder base or anus. Palpation is important to determine possible involvement of the surrounding bony structures. Discomfort and tenderness may necessitate an examination (and biopsies) under general anaesthesia. The groin should be examined, although a negative assessment cannot reliably exclude cancer. Hard, enlarged, fixed or ulcerated nodes (Figure 41.3) need to be documented as this will almost certainly influence management.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based upon a representative biopsy of the tumour. The biopsy should include an area where there is a transition from normal to malignant tissue (Figure 41.4). Biopsies should be of a sufficient size to allow differentiation between superficially invasive tumours and frankly invasive tumours, and orientated to allow quality pathological interpretation. Radical excision should not be undertaken without prior biopsy confirmation of malignancy unless there are extenuating circumstances.

Staging

There are two staging systems: the Tumour, Node, Metastasis system and the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) system. Most gynaecologists use the latter which, since its last update in 2000, is based upon clinical and surgical findings. Table 41.2 details both staging systems.

| FIGO stage | Description |

|---|---|

| I | Tumour confined to the vulva |

| Ia | Lesions ≤2 cm in size, confined to the vulva or perineum and with stromal invasion ≤1 mm. No nodal metastasis |

| Ib | Lesions >2 cm in size or with stromal invasion >1 mm confined to the vulva or perineum. No nodal metastasis |

| II | Tumour of any size with extension to adjacent perineal structures (lower 1/3 urethra; lower 1/3 vagina; anus) with negative nodes |

| III | Tumour of any size with or without extension to adjacent perineal structures (lower 1/3 urethra; lower 1/3 vagina; anus) with positive inguinofemoral nodes |

| IIIa |

FIGO, International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics.

Prognostic Factors

The size of the primary tumour and the status of the regional lymph nodes are the only two factors that have been consistently associated with outcome (Homesley et al 1991). The 5-year survival rate in cases without lymph node involvement is in excess of 80%, falling to less than 50% if the inguinal nodes are involved and 10–15% if the iliac or other pelvic nodes are involved.

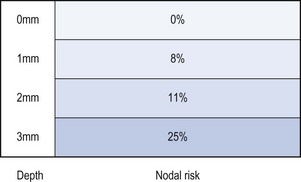

Depth of invasion

Invasion less than 1 mm (superficially invasive or stage Ia) has a negligible risk of lymph node involvement, and groin node dissection may be omitted (Hacker et al 1984b). The risk of nodal metastasis rises to 8% for a depth of 1–2 mm, 11% for 2–3 mm, and over 25% for lesions with a depth greater than 3 mm (Morrow et al 1993) (Figure 41.5).

Lymphovascular space permeation

This factor along with tumour border pattern (infiltrating vs pushing) and perineural invasion are not included in the surgicopathological staging of vulvar cancer, although they are associated with an increased risk of metastasis (Heaps et al 1990, Hopkins et al 1991).

Lymph node status

This is the most important prognostic variable. The number of lymph nodes involved and the nature of involvement influence the prognosis. Microscopic involvement of a single groin node, without extracapsular involvement, represents a low risk of recurrence, and adjuvant therapy is not necessary (Hacker et al 1983). Conversely, multiple nodal diseases and macroscopic and/or capsular involvement are indications for adjuvant radiotherapy in order to reduce the risk of groin recurrence, which is usually fatal (van der Velden et al 1995). It is well recognized that groin node dissection is associated with significant morbidity. Almost 50% of patients undergoing groin node dissection will suffer postoperative complications, most commonly wound infection, wound breakdown and lymphoedema (Gaarenstroom et al 2003). For these reasons, a presurgical investigation that could identify those at risk could have a significant therapeutic benefit. Assessment by clinical palpation of the groins is inadequate; of patients with clinically normal lymph nodes, 16–24% have metastases, while 24–41% of those with clinically involved nodes are negative when examined histologically (Sedlis et al 1987, Homesley et al 1993). Even though the majority of vulval cancers are still assessed clinically, there is increasing interest in utilizing additional imaging, particularly of the regional node groups. Ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography have all been assessed but lack the sensitivity to exclude microscopic disease reliably (Selman et al 2005). Sentinel node sampling (vide infra) has shown promise, and the collective experience of this technique now suggests that it is reliable, at least in early-stage disease.

Sentinel lymph node detection

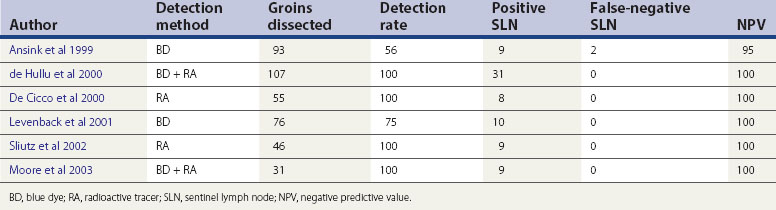

The concept of the ‘sentinel lymph node’ (SLN) was introduced in 1977 by Cabanas (1977). He defined the SLN as the first node in the lymphatic basin that receives primary lymphatic flow. Subsequent studies have confirmed that a tumour-free SLN implies absence of lymph node metastases in the entire draining lymphatic basin (Balega and van Trappen 2006). The last two decades have seen the technique become established in the management of cutaneous melanoma and breast cancer. The concept (Figure 41.6) has now been introduced for the management of early vulval cancers, and the published performance data to date are promising (Table 41.3).

A large-scale international trial, the Groningen International Study on Sentinel Nodes in Vulvar Cancer (GROINSS-V), was established to test the safety and clinical utility of SLN dissection in early-stage vulvar cancer. This was an observational study. Patients with stage I and II disease with tumour size less than 4 cm were recruited. Only patients found to have disease in either SLN underwent full inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy. Among 259 patients with unifocal vulvar cancer and a negative sentinel node, groin recurrences occurred in six (2.3%) women, and the 3-year survival rate was 97%. This result was comparable with similar historical groups of patients that had full inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy. However, both short- and long-term morbidity were significantly reduced, including shorter hospital stay and less wound breakdown and lymphoedema (van der Zee et al 2008). The authors thus proposed that sentinel node dissection should be the standard treatment for patients with unifocal early-stage vulvar cancer. In the second phase of the GROINSS-V study, investigators are evaluating radiotherapy, rather than complete inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy, in patients with metastatic SLNs. The objective is to further reduce morbidity by avoiding double-modality treatment.

Treatment

Factors influencing the management plan

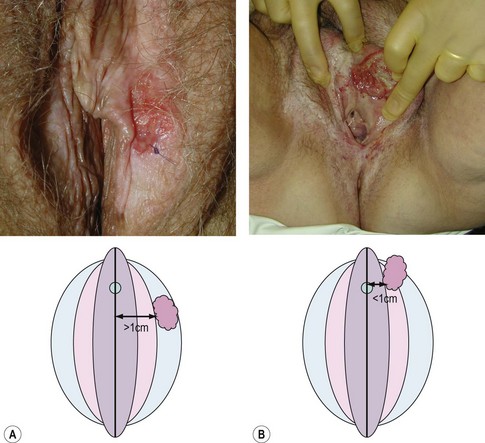

Site of the tumour

Centrally located tumours lie close to midline structures such as the clitoris, urethra, vagina and anus, and are associated with a higher risk of bilateral inguinal nodal spread compared with more lateral tumours. If the medial margin lies within 1 cm of the midline, they should be defined as central (de Hullu and van der Zee 2006). Bilateral groin node dissection is recommended for central tumours, and ipsilateral groin node dissection is recommended for lateralized tumours (Figure 41.7). Furthermore, if central tumours approximate to the urethra or anal canal such that these structures would be sacrificed to achieve satisfactory clearance, urinary or bowel diversion may be necessary.

Surgery

Surgery is the mainstay of treatment. The traditional ‘butterfly’ incision en-bloc radical (Figure 41.8) vulvectomy introduced by Taussig (1940) and Way (1960) clearly improved survival. The excised tissues included the vulvar lesion, the inguinofemoral lymph nodes and the lymphatics in between. Large areas of normal tissue were frequently included, and primary wound closure was rarely achieved. Protracted postoperative recovery and severe wound complications and disfigurement were associated with this procedure. This postoperative morbidity has been the main driver for progress over the last two decades. Surgical treatment has become more individualized and conservative, aimed at reducing morbidity without compromising survival.

Separate incisions

The use of three separate incisions for groin dissections and vulvectomy instead of the traditional ‘butterfly incision’ has improved wound healing and reduced the frequency of wound breakdown (Hacker et al 1981). The suggestion that this lesser approach might result in an increase in skin bridge recurrence was not born out in a Cochrane review, which showed a skin bridge recurrence rate of less than 1% (Ansink and van der Velden 2000). The hypothesis underpinning this strategy is based upon the belief that in early tumours, cells disseminate by embolization rather than in continuity (Willis 1973); therefore, there should be no residual tumour in the lymphatic channels between the tumour and the groin nodes. Reported cases of skin bridge recurrences were mainly seen in women with large groin node metastasis (Rose 1999). No prospective randomized controlled studies have been performed comparing the traditional radical vulvectomy with en-bloc inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy with the separate incision technique. However, de Hullu et al (2002) did undertake a retrospective comparison and noted a significant increase in groin and skin bridge recurrence with the less radical procedure (6.3% vs 1.3%, P=0.029). This, however, did not result in a difference in overall survival. They concluded that in view of the morbidity of the ‘butterfly incision’ and relatively low skin bridge recurrence rate, separate incisions were the preferable technique for stage I and II disease.

Modified radical vulvectomy or wide local excision

The main factor causing severe morbidity and disfigurement following radical vulvectomy is the extensive dissection and removal of normal tissue from the vulvar region. In the last two decades, less radical surgery, such as modified radical vulvectomy, hemivulvectomy and wide local excision, has been introduced to reduce morbidity without compromising survival. Tumour-free margins are the most important predictive factor for local recurrences. Both Heaps et al (1990) and de Hullu et al (2002) showed that a tumour-free margin of more than 8 mm was associated with significantly lower local recurrence rate. These studies found that suboptimal tumour-free margins (<8 mm) were more likely when the intentional macroscopic margin was 1 cm or less. A lesion might extend further than judged by macroscopic inspection, and tissues usually shrink during preparation for histological examination (Balega et al 2008). A macroscopic surgical margin of 2 cm is thus recommended. This may be difficult to achieve in some cases where the tumour is adjacent to the urethra and anus, but every effort should be made to maximize the margins. The tumour-free margins should be the same regardless of whether a radical vulvectomy or a wide local excision is performed.

Unilateral inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy

Lateralized vulvar tumours rarely metastasize to the contralateral inguinofemoral lymph nodes without the ipsilateral nodes being involved. van der Velden (1996) pooled 489 patients with unilateral vulvar cancers and found only 0.9% with isolated contralateral lymph node metastases in lateralized stage I disease. Similarly, Gonzalez Bosquet et al (2007) reviewed 320 patients who underwent bilateral groin lymph node dissection. Among 163 patients with unilateral vulvar lesions, only three (1.8%) had an isolated contralateral nodal metastasis. No patients with a tumour diameter equal to or less than 2 cm and depth of invasion less than 5 mm had bilateral groin lymph node involvement. Given the recognized higher morbidity and low numbers of patients with contralateral metastases, it is now a generally accepted practice to perform a unilateral inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy in patients with stage I and II lateralized tumours, without suspicious lymph nodes on palpitation. If nodal disease is found in one groin, the opposite groin should also be explored. Normal lymph flow may be disturbed in cases of ipsilateral groin node metastases with alternate channels developing, thus allowing contralateral spread.

Superficial inguinal lymphadenectomy

In order to reduce lymphoedema and wound breakdown associated with groin dissection, DiSaia et al (1979) proposed removing only the superficial inguinal lymph nodes lying anterior to the cribriform fascia, without exploration of the deeper femoral nodes. The rationale for this was that lymphatic drainage from the vulva passes first to the superficial inguinal nodes before subsequently draining to the femoral nodes. The superficial inguinal nodes were assessed by frozen section, and a deep dissection was performed if the superficial nodes were found to be positive. However, the results of subsequent studies have not been encouraging. Unexpected groin recurrences occurred in patients with early-stage disease and presumed negative inguinal nodes (Hacker et al 1984b, Kelley et al 1992, Stehman et al 1992a). The current practice is that a full inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy including all superficial inguinal lymph nodes and femoral lymph nodes medial to the femoral veins should be performed whenever there is an indication for node dissection.

Pelvic lymphadenectomy

Routine pelvic lymphadenectomy is no longer considered in the surgical management of vulvar carcinoma. The incidence of pelvic node metastases is approximately 5% and is very rare in the absence of inguinofemoral lymph node metastases (Gadducci et al 2006). One randomized trial (Homesley et al 1986) compared pelvic lymphadenectomy with pelvic radiotherapy in patients with inguinofemoral lymph node metastases after radical vulvectomy and bilateral inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy. The 2-year survival rate for the radiation group was significantly better than that for the pelvic lymphadenectomy group (68% vs 54%, P<0.03). The incidence of groin recurrence was less in the radiation group (5.1% vs 23.6%, P<0.02). However, the rate of pelvic recurrence was increased in patients who received pelvic irradiation. It was postulated that radiation may not be able to sterilize bulky pelvic metastatic nodes. Therefore, removal of enlarged pelvic nodes seen on CT scan via an extraperitoneal approach was suggested before starting radiotherapy.

Vulvar morbidity

Problems with micturition (spraying, angulation of urine, urethral stenosis) are not uncommon if the distal third of the urethra is excised. Surgery for perineal and perianal lesions may give rise to problems with defaecation (constipation, tenesmus and faecal incontinence), localized pain when sitting and coital difficulties (Barton 2003). Occasionally, repeat surgery is needed to excise fibrotic tissue or to widen the stenotic introitus in order to facilitate coitus.

Groin morbidity

Lymphocysts and infection are the two most common short-term groin complications. Despite the routine use of drains and antibiotics, complications are still as high as 66% (Gaarenstroom et al 2003). More troublesome is the long-term complication of lower limb lymphoedema, which is often difficult to treat and can cause significant distress to patients. The incidence of lymphoedema is further increased if adjuvant radiotherapy is given after surgery (Barton 2003). The simplest approach to reduce groin morbidity is less radical surgery and avoidance of double treatment. SLN dissection goes some way to addressing this need without compromising disease control, at least in early vulval cancer. The incidence of wound breakdown, infection and lymphoedema decreased to 11.7%, 4.5% and 1.9%, respectively (van der Zee et al 2008).

Postoperative adjuvant therapy

Patients with risk factors for local recurrence, such as a close surgical margin, lymphovascular space permeation, poorly differentiated tumour grade or diffuse infiltrative growth pattern, should be considered for adjuvant external beam radiation therapy to reduce the risk of recurrence (Perez et al 1998, Blake 2003).

With regard to the nodal status, no additional treatment is recommended if there is only one microscopically positive lymph node (Hacker et al 1983). However, if two or more metastatic nodes are present, or there is capsular involvement in a single metastatic node, postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy is usually recommended (van der Velden et al 1995). In a subgroup analysis of Homesley et al’s study, the survival advantage of radiotherapy was limited to those patients with clinically evident groin nodes or more than one positive groin node (Homesley et al 1986).

Neoadjuvant therapy

In order to achieve an adequate surgical margin with large tumours close to the urethra and/or anal canal, it may be necessary to compromise urethral and/or anal function with an associated diversion. In 1973, Boronow suggested a combined radiosurgical approach to shrink the tumour preoperatively, aiming to spare this group of patients from exenterative surgery. Subsequent reports (Hacker et al 1984a, Boronow et al 1987) confirmed the feasibility of this function-sparing approach. More recently, concurrent chemoradiation has been used with the same intent. Moore et al (1998) gave concurrent cisplatin/5-fluorouracil (5FU) and radiation therapy to 71 patients with stage III–IV disease. Thirty-three patients (46.5%) had no visible tumour after chemoradiation, and only three patients were not able to preserve urinary and/or gastrointestinal continence after surgery. van Doorn et al (2006) reviewed the available literature and concluded that preoperative chemoradiotherapy reduces tumour size and improves operability. However, complications are considerable, especially in delayed wound healing, and overall increased treatment-related morbidity.

Primary treatment

Radiotherapy alone as a treatment for vulvar cancer is not recommended in operable tumours, mainly because of the perceived intolerance of vulvar tissue. However, it is an option in patients who cannot undergo surgery because of advanced disease or comorbidity issues. In selected cases, primary radiotherapy can cure vulvar cancer with acceptable morbidity (Busch et al 1999). Chemotherapy can be added to the regimen, either as a neoadjuvant to reduce tumour bulk or as concomitant chemoradiotherapy to improve cure rates (Moore et al 1998).

Although the groin tolerates radiotherapy better than the vulva, primary radiotherapy to treat groin disease is not recommended. One study has reported a higher recurrence rate when comparing radiation therapy with inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy (Stehman et al 1992b). However, this study has been criticized on the basis of suboptimal radiotherapy technique, particularly that the maximum dose did not reach the deep inguinofemoral nodes. More recently, Katz et al (2003) re-evaluated the value of primary radiotherapy for groin disease. Comparable recurrence rates were observed when radiotherapy alone was compared with inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy (15% vs 16.6%). The authors concluded that radiotherapy alone was as effective as surgery in preventing groin recurrence. This study was criticized largely because of difficulties in interpreting the individualized treatment. There were also doubts about the radicality of lymphadenectomy.

Chemotherapy

The role of chemotherapy in vulvar cancer is either as concomitant therapy with radiation or as a palliative manoeuvre in recurrent or metastatic disease. Several cytotoxic drugs (cisplatin, methotrexate, bleomycin, mitomycin C and 5FU) have been shown to have activity when used alone or in combination (Shimizu et al 1990, Benedetti Panici et al 1993). 5FU appears to be the most effective agent. In a series of 12 patients with advanced vulvar cancer involving either or both the anus and urethra, a combination of cisplatin and 5FU gave a 100% response rate. The anal sphincter and urethra were conserved in these patients during subsequent radical surgery. However, three patients receiving cisplatin alone showed no response or even progression (Geisler et al 2006). However, all of the studies were small and uncontrolled, and should be interpreted with caution.

Advanced Disease

Advanced vulvar cancer (T3/T4) is characterized by local extension to neighbouring structures (urethra, vagina, bladder and anus). Regional lymph node metastases are present in over 50% of these patients (Hacker et al 1983). Ultraradical surgery with urinary tract and/or bowel diversion is required for complete excision. Unfortunately, most of these patients are elderly and frail, having significant comorbidities rendering them unsuitable for such extensive surgery. Radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy can shrink some tumours before surgery, sparing them from stoma formation and reducing surgical morbidity (Hacker et al 1984a, Boronow et al 1987). Furthermore, preoperative chemoradiation can result in fixed groin nodes becoming resectable (Montana et al 2000). Radiation therapy with or without concurrent chemotherapy should be considered as an alternative option for patients with advanced vulvar cancer who would otherwise require exenterative surgery.

Recurrences

Rouzier et al (2002) identified three patterns of local recurrence:

Tumour size, surgical margins and depth of invasion (Rouzier et al 2002) are risk factors for primary site relapse. It is usually salvageable with repeat surgical excision or radiotherapy (Thomas et al 1989, Hopkins et al 1990). Local recurrence remote from the primary tumour site should be considered as a new primary lesion and is seen more frequently in patients with a background of lichen sclerosus or differentiated VIN. Again, surgical excision is the first choice of treatment. The prognosis is generally good, with more than 60% of patients surviving for more than 3 years. Patients with skin bridge recurrence seldom live for more than 1 year (Rouzier et al 2002).

Almost one-third of all recurrences occur in the groin. Groin recurrence is seen more often when previous node dissection was omitted, or when positive nodes were present at primary surgery. The prognosis is poor, with more than 90% of patients dying within 1 year (Hacker et al 1984b).

Malignant Melanoma

Malignant melanoma is the second most common vulvar malignancy, accounting for 5–10% of cases of vulvar cancer. The incidence is less than 0.2 per 100,000 women per year (Piura 2008). It is a disease of the elderly, occurring in the fifth to seventh decades, and is more common in Caucasians. They usually present with a vulvar mass, bleeding and pruritus. The labia minora, clitoris or inner aspects of the labia majora are the most common sites. A variety of pigmented lesions mimic vulvar melanoma, including vulvar melanosis, different types of nevi and acanthosis nigricans. Biopsy is essential for diagnosis. Three histological subtypes have been described (Ragnarsson-Olding et al 1999a):

Up to 25% of tumours are amelanotic.

Various staging systems have been proposed for vulvar melanoma. The most commonly used are the Clark et al (1969), Breslow (1970) and Chung et al (1975) systems. However, in 1994, a Gynecologic Oncology Group study showed that the American Joint Committee on Cancer melanoma staging system is more accurate in predicting outcome (Phillips et al 1994).

Radical vulvectomy has been recommended for vulvar melanoma in the past. However, the available literature suggests no survival difference in patients having a radical vulvectomy, simple vulvectomy or wide local excision (Rose et al 1988, Tasseron et al 1992). The current consensus is to aim for a tumour-free margin of at least 1 cm for tumour less than 1 mm thick, a tumour-free margin of 2 cm for tumours 1–4 mm thick, and a tumour-free margin of at least 1 cm at the subcutaneous layer for all cases. The role of elective regional node dissection is controversial for both cutaneous and vulvar melanoma. A prospective study by the Gynecologic Oncology Group in 1994 failed to find a definite survival benefit for elective lymph node dissection in patients with vulvar melanoma (Phillips et al 1994). The role of adjuvant therapy for treatment of vulvar melanoma is also unclear. Radiotherapy has been suggested for incomplete tumour resection or positive groin/pelvic lymph nodes (Piura 2008). Interferon α-2b seems to be a promising adjuvant therapy for cutaneous melanoma (Kirkwood et al 2001), but data in vulvar melanoma are lacking.

Vulvar melanoma is usually highly aggressive, with a tendency to recur locally and spread haematogenously to distant organs such as the liver, lung and brain. Reported 5-year survival rates range from 21% to 54% (Podratz et al 1983b, Blessing et al 1991, Ragnarsson-Olding et al 1999b, Verschraegen et al 2001). As with cutaneous melanoma, the survival rate correlates with depth of invasion.

Bartholin’s Gland Carcinoma

Primary carcinoma of Bartholin’s gland is rare, accounting for 0.1–7% of all vulvar carcinomas (Nasu et al 2005). Bartholin’s gland carcinomas may initially be confused with Bartholin’s cyst or an abscess. The tumour may arise from either the gland or the duct, thus various histological types may occur, including adenocarcinomas, squamous carcinomas, transitional cell carcinomas, adenosquamous carcinomas and adenoid cystic carcinomas. Since most of these lesions are located deep in the vulva, radical excision usually involves removing part of the vagina, levator muscles and the ischiorectal fat in order to achieve an adequate tumour-free margin. If regional groin or pelvic lymph nodes are positive, adjuvant radiotherapy is indicated to reduce the risk of recurrence (Copeland et al 1986). Adenoid cystic carcinoma is a rare variant, characterized by slow growth, with a marked tendency for perineural and local invasion. The tumour seldom metastasizes and carries a better prognosis (Nasu et al 2005).

Invasive Paget’s Disease

Paget’s disease of the vulva is a rare intraepithelial neoplasia, probably originating from the vulvar apocrine glands. Approximately 10% of cases are invasive and 4–8% are associated with adenocarcinoma (Fanning et al 1999). The disease predominantly affects postmenopausal Caucasian women, usually presenting with vulvar pruritus and soreness. The lesion is usually multifocal, well demarcated and characterized by red eczematous patches (Figure 41.9). These originate on the hair-bearing regions of the vulva. Notoriously, vulvar Paget’s disease extends beyond the macroscopic lesions, and recurrence frequently occurs despite a clear surgical margin obtained at wide local excision (MacLean et al 2004). Thus, it is not uncommon for patients to undergo multiple recurrences and re-excisions over years of surveillance. In the event of finding invasive carcinoma, the patient should be treated with radical vulvectomy and groin node dissection, as for squamous cell carcinoma.

Verrucous Carcinoma

Verrucous carcinoma is a rare variant of squamous cell carcinoma, characterized by local invasion without nodal or distant metastases. The gross appearance resembles a giant condyloma. Histologically, there is an exophytic papillary component of well-differentiated squamous epithelium with hyperparakeratosis and well-demarcated pushing borders. The treatment is modified radical vulvectomy. Lymphadenectomy is not indicated (Finan 2003).

Basal Cell Carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma accounts for approximately 2–4% of all cases of vulvar cancer. It usually appears as a small (1–2 cm), raised, nodular lesion with well-defined edges. Wide local excision with a 1 cm margin is usually curative, and recurrence and metastases are rare (Mulayim et al 2002).

Sarcoma

Vulvar sarcoma is extremely rare and treatment options are derived from anecdotal case reports. Leiomyosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, dermatofibrosacroma protuberans and epithelioid sarcoma are all reported in the literature. The usual treatment is radical vulvectomy and groin node dissection (Aartsen and Albus-Lutter 1994, Hensley 2000).

Cancer of The Vagina

Introduction

Vaginal carcinoma accounts for less than 2% of gynaecological cancers (Kirkbride et al 1995). In 2005, 216 cases were registered in the UK, equivalent to 0.8/100,000 women (Office of National Statistics 2008). Seventy percent of these patients were 60 years of age or older. Squamous cell carcinoma was the most common variant (Grigsby 2002). The evidence base is drawn from case reports and retrospective reviews.

Aetiology

The exact aetiology for primary vaginal cancer is unknown. Up to one-third of patients have a history of a cervical lesion, either benign or malignant (Peters et al 1985). Stock et al (1995) reviewed 100 cases of vaginal cancer and found that patients who had a previous hysterectomy were more likely to develop a lesion in the upper third of the vagina compared with women who had not had an hysterectomy (62% vs 34%, P<0.005). Possible explanations for this are: occult residual disease from a cervical lesion, HPV as a persisting carcinogenic agent (Daling et al 2002), an effect of radiation therapy given for previous genital tract cancer may induce vaginal cancer, and the disease interval is usually more than 10 years (Chaturvedi et al 2007).

Similar to cervical cancer, there is a premalignant condition in the vagina, vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN). However, the true malignant potential of VAIN is unclear. Vaginal cancer caused by chronic irritation, such as procidentia and vaginal pessaries, has been reported (Ghosh et al 2009) but the incidence is extremely low. Intrauterine exposure to diethylstilboestrol was thought to be a causative agent for clear cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina in the past (Herbst et al 1971). However, with the cessation of its use in the 1970s, it is rarely seen nowadays.

Pathology

More than 80% of primary vaginal tumours are squamous cell carcinomas; adenocarcinomas are the second most common, accounting for approximately 15% (Grigsby 2002). The remainder are sarcomas, malignant melanomas, small cell carcinomas, lymphomas and carcinoid tumours. Metastatic lesions from non-gynaecological sites have also been reported, including bladder, kidney, colon and rectum (Tarraza et al 1998, Parikh et al 2008).

Clinical assessment

The most common presenting symptoms are painless vaginal bleeding (81%) and abnormal discharge (33%) (Pingley et al 2000). Large, posteriorly sited tumours may cause tenesmus. When disease has spread beyond the vagina, patients may present with pelvic pain. Occasionally, vaginal cancer may be recognized after an abnormal Pap smear (Pride et al 1979).

The majority of lesions are located in the upper posterior vagina, usually in the form of an exophytic mass with contact bleeding (Pingley et al 2000). It is not uncommon to miss a small lower vaginal lesion at the initial examination, when it may be hidden by the blades of the speculum. If vaginal cancer is to be excluded, a full and thorough inspection of the entire vagina is required.

In order to make a diagnosis of vaginal cancer, apart from histological confirmation, certain criteria are to be met (Benedet et al 2000):

Staging

The FIGO staging system for vaginal cancer is shown in Table 41.4. It is a clinical staging system based on findings from physical examination, cystoscopy, proctoscopy and chest X-ray.

Table 41.4 International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging for carcinoma of the vagina

| FIGO stage | Description |

|---|---|

| Stage 0 | Carcinoma in situ, intraepithelial carcinoma, high-grade vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia |

| Stage I | The carcinoma is limited to the vaginal wall |

| Stage II | The carcinoma has invaded the subvaginal tissues but has not extended on to the pelvic sidewall |

| Stage IIa | The carcinoma has invaded the subvaginal tissues but has not extended to the parametrium |

| Stage IIb | The carcinoma involves the parametrium but has not extended to the pelvic sidewall |

| Stage III | The carcinoma has extended to the pelvic sidewall |

| Stage IV | The carcinoma extends beyond the true pelvis or has clinically involved the mucosa of the bladder or rectum. Bullous oedema as such does not permit a case to be allocated to stage IV |

| Stage IVa | The carcinoma has spread to adjacent organs and/or direct extension beyond the true pelvis |

| Stage IVb | The carcinoma has spread to distant organs |

Treatment

Radiotherapy is the most commonly used treatment modality for vaginal cancer. The close proximity of the bladder and rectum limit the ability of surgery to radically excise tumour without significant functional compromise. Exenterative surgery is often needed in order to achieve adequate margins, especially with lower vaginal tumours (Figure 41.10).

Both teletherapy and brachytherapy are used in managing these cancers. A number of reports have shown that sequential use of teletherapy followed by brachytherapy results in a better outcome (Perez et al 1999, Pingley et al 2000). External radiation is used to treat disease with lateral infiltration; the irradiation field is similar to that for cervical cancer. The pelvis receives 50 Gy, covering the side walls, pelvic nodes and the whole vagina (Grigsby 2002). The irradiation field should be extended to the groin if the tumour is located in the lower third of the vagina. External beam irradiation also results in shrinkage of large tumours, facilitating subsequent brachytherapy. Interstitial implants using premade templates may be indicated for deeply invasive tumours. Early-stage disease (stage I–II) may be treated by brachytherapy alone.

Although surgery has a limited role in the treatment of vaginal cancer, it is indicated in certain situations. Stage I–II upper vaginal lesions can be treated surgically. Upper vaginectomy in combination with radical hysterectomy and bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy can be performed for patients with an intact uterus. If the patient has had a hysterectomy, radical upper vaginectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy may be considered. In a retrospective study of 89 stage I and II patients, Davis et al (1991) reported no survival differences when comparing surgery and radiotherapy.

Prognosis

Staging is the only consistent prognostic factor in predicting outcome. The 5-year survival rates for stage I, II, III and IV disease are 73%, 51%, 33% and 20%, respectively (Beller et al 2001).

Uncommon vaginal tumours

Rhadbomyosarcoma (sarcoma botryoides)

This rare tumour mainly affects children below 5 years of age. The polypoid tumour protrudes from the vagina, resembling a bunch of grapes. Treatment is based upon primary chemotherapy using vincristine, actinomycin D and cyclophosphamide plus doxorubicin, followed by conservative organ-sparing surgery or radiotherapy. Survival rates of over 80% are now achievable (Andrassy et al 1999, Harting et al 2004).

Clear cell adenocarcinoma

Approximately 15% of primary vaginal cancers are adenocarcinomas, predominantly affecting young women. In the main, they arise from vaginal adenosis, which is a consequence of disrupted Müllerian development. This malformation may or may not be related to in-utero diethylstilboestrol exposure (Herbst and Anderson 1990). The treatment is similar to that of squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina. However, every effort should be made to retain vaginal and ovarian function as most of these patients are still in their reproductive years.

Malignant melanoma

Primary malignant melanoma of the vagina constitutes less than 0.3% of all melanomas and less than 3% of malignant vaginal tumours (Siu et al 2004). It is highly malignant and is notoriously more aggressive than non-genital and vulvar melanoma. Most patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage with a deeply invasive tumour. The 5-year survival rate is 17%. Radical surgery does not appear any better than conservative surgery (wide local excision) in terms of survival (Reid et al 1989). Radiotherapy is mainly used as an adjuvant therapy to decrease recurrence.

KEY POINTS

Aartsen EJ, Albus-Lutter CE. Vulvar sarcoma: clinical implications. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 1994;56:181-189.

Andrassy RJ, Wiener ES, Raney RB, et al. Progress in the surgical management of vaginal rhabdomyosarcoma: a 25-year review from the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 1999;34:731-735.

Ansink AC, Heintz AP. Epidemiology and etiology of squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 1993;48:111-115.

Ansink AC, Sie-Go DM, van der Velden J, et al. Identification of sentinel lymph nodes in vulvar carcinoma patients with the aid of a patent blue V injection: a multicenter study. Cancer. 1999;86:652-656.

Ansink A, van der Velden J 2000 Surgical interventions for early squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2: CD002036.

Balega J, van Trappen PO. The sentinel node in gynaecological malignancies. Cancer Imaging. 2006;6:7-15.

Balega J, Butler J, Jeyarajah A, et al. Vulval cancer: what is an adequate surgical margin? European Journal of Gynaecological Oncology. 2008;29:455-458.

Barton DPJ. The prevention and management of treatment related morbidity in vulval cancer. Best Practice and Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2003;17:683-701.

Beller U, Sideri M, Maisonneuve P, et al. Carcinoma of the vagina. Journal of Epidemiology and Biostatistics. 2001;6:141-152.

Benedet JL, Bender H, Jones H3rd, Ngan HY, Pecorelli S. FIGO staging classifications and clinical practice guidelines in the management of gynecologic cancers. FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2000;70:209-262.

Benedetti-Panici P, Greggi S, Scambia G, Salerno G, Mancuso S. Cisplatin (P), bleomycin (B), and methotrexate (M) preoperative chemotherapy in locally advanced vulvar carcinoma. Gynecologic Oncology. 1993;50:49-53.

Blake P. Radiotherapy and chemoradiotherapy for carcinoma of the vulva. Best Practice and Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2003;17:649-661.

Blessing K, Kernohan NM, Miller ID, Al Nafussi AI. Malignant melanoma of the vulva: clinicopathological features. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 1991;1:81-87.

Boronow RC. Therapeutic alternative to primary exenteration for advanced vulvovaginal cancer. Gynecologic Oncology. 1973;1:233-255.

Boronow RC, Hickman BT, Reagan MT, Smith RA, Steadham RE. Combined therapy as an alternative to exenteration for locally advanced vulvovaginal cancer. II. Results, complications, and dosimetric and surgical considerations. American Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1987;10:171-181.

Bradgate MG, Rollason TP, McConkey CC, Powell J. Malignant melanoma of the vulva: a clinicopathological study of 50 women. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1990;97:124-133.

Breslow A. Thickness, cross-sectional areas and depth of invasion in the prognosis of cutaneous melanoma. Annals of Surgery. 1970;172:902-908.

Busch M, Wagener B, Dühmke E. Long-term results of radiotherapy alone for carcinoma of the vulva. Advances in Therapy. 1999;16:89-100.

Cabanas RM. An approach for the treatment of penile carcinoma. Cancer. 1977;39:456-466.

Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Gilbert ES, et al. Second cancers among 104,760 survivors of cervical cancer: evaluation of long-term risk. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2007;99:1634-1643.

Chung AF, Woodruff JM, Lewis JLJr. Malignant melanoma of the vulva: a report of 44 cases. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1975;45:638-646.

Clark WHJr, From L, Bernardino EA, Mihm MC. The histogenesis and biologic behavior of primary human malignant melanomas of the skin. Cancer Research. 1969;29:705-727.

Copeland LJ, Sneige N, Gershenson DM, McGuffee VB, Abdul-Karim F, Rutledge FN. Bartholin gland carcinoma. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1986;67:794-801.

Crum CP, McLachlin CM, Tate JE, Mutter GL. Pathobiology of vulvar squamous neoplasia. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1997;9:63-69.

Daling JR, Madeleine MM, Schwartz SM, et al. A population-based study of squamous cell vaginal cancer: HPV and cofactors. Gynecologic Oncology. 2002;84:263-270.

Davis KP, Stanhope CR, Garton GR, Atkinson EJ, O’Brien PC. Invasive vaginal carcinoma: analysis of early-stage disease. Gynecologic Oncology. 1991;42:131-136.

De Cicco C, Sideri M, Bartolomei M, et al. Sentinel node biopsy in early vulvar cancer. British Journal of Cancer. 2000;82:295-299.

de Hullu JA, Hollema H, Piers DA, et al. Sentinel lymph node procedure is highly accurate in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Journal of. Clinical Oncology. 2000;18:2811-2816.

de Hullu JA, Hollema H, Lolkema S, et al. Vulvar carcinoma. The price of less radical surgery. Cancer. 2002;95:2331-2338.

de Hullu JA, van der Zee AGJ. Surgery and radiotherapy in vulvar cancer. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2006;60:38-58.

DiSaia PJ, Creasman WT, Rich WM. An alternate approach to early cancer of the vulva. American Journal of Obstetrics Gynecology. 1979;133:825-832.

Fanning J, Lambert HC, Hale TM, Morris PC, Schuerch C. Paget’s disease of the vulva: prevalence of associated vulvar adenocarcinoma, invasive Paget’s disease, and recurrence after surgical excision. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;180:24-27.

Finan MA. Bartholin’s gland carcinoma, malignant melanoma and other rare tumours of the vulva. Best Practice and Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2003;17:609-633.

Fishman DA, Chambers SK, Schwartz PE, Kohorn EI, Chambers JT. Extramammary Paget’s disease of the vulva. Gynecologic Oncology. 1995;56:266-267.

Gaarenstroom KN, Kenter GG, Trimbos JB, et al. Postoperative complications after vulvectomy and inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy using separate groin incisions. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 2003;13:552-557.

Gadducci A, Cionini L, Romanini A, Fanucchi A, Genazzani AR. Old and new perspectives in the management of high-risk, locally advanced or recurrent, and metastatic vulvar cancer. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2006;60:227-241.

Geisler JP, Manahan KJ, Buller RE. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in vulvar cancer: avoiding primary exenteration. Gynecologic Oncology. 2006;100:53-57.

Ghosh SB, Tripathi R, Mala YM, Khurana N. Primary invasive carcinoma of vagina with third degree uterovaginal prolapse: a case report and review of literature. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2009;279:91-93.

Gonzalez Bosquet J, Magrina JF, Magtibay PM, et al. Patterns of inguinal groin metastases in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Gynecologic Oncology. 2007;105:742-746.

Grigsby PW. Vaginal cancer. Current Treatment Options in Oncology. 2002;3:125-130.

Hacker NF, Leuchter RS, Berek JS, Castaldo TW, Lagasse LD. Radical vulvectomy and bilateral inguinal lymphadenectomy through separate groin incisions. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1981;58:574-579.

Hacker NF, Berek JS, Lagasse LD, Leuchter RS, Moore JG. Management of regional lymph nodes and their prognostic influence in vulvar cancer. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1983;61:408-412.

Hacker NF, Berek JS, Juillard GJ, Lagasse LD. Preoperative radiation therapy for locally advanced vulvar cancer. Cancer. 1984;54:2056-2061.

Hacker NF, Berek JS, Lagasse LD, Nieberg RK, Leuchter RS. Individualization of treatment for stage I squamous cell vulvar carcinoma. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1984;63:155-162.

Harting MT, Blakely ML, Andrassy RJ. Surgical management of gynecologic rhabdomyosarcoma. Current Treatment Options in Oncology. 2004;5:109-118.

Heaps JM, Fu YS, Montz FJ, Hacker NF, Berek JS. Surgical-pathologic variables predictive of local recurrence in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Gynecologic Oncology. 1990;38:309-314.

Hensley ML. Uterine/female genital sarcomas. Current Treatment Options in Oncology. 2000;1:161-168.

Herbst AL, Ulfelder H, Poskanzer DC. Adenocarcinoma of the vagina. Association of maternal stilbestrol therapy with tumor appearance in young women. New England Journal of Medicine. 1971;284:878-881.

Herbst AL, Anderson D. Clear cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina and cervix secondary to intrauterine exposure to diethylstilbestrol. Seminars in Surgical Oncology. 1990;6:343-346.

Herod JJ, Shafi MI, Rollason TP, Jordan JA, Luesley DM. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: long term follow up of treated and untreated women. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1996;103:446-452.

Homesley HD, Bundy BN, Sedlis A, Adcock L. Radiation therapy versus pelvic node resection for carcinoma of the vulva with positive groin nodes. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1986;68:733-740.

Homesley HD, Bundy BN, Sedlis A, et al. Assessment of current International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging of vulvar carcinoma relative to prognostic factors for survival (a Gynecologic Oncology Group study). American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1991;164:997-1003. discussion 1003–1004

Homesley HD, Bundy BN, Sedlis A, et al. Prognostic factors for groin node metastasis in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva (a Gynecologic Oncology Group study). Gynecologic Oncology. 1993;49:279-283.

Hopkins MP, Reid GC, Morley GW. The surgical management of recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1990;75:1001-1005.

Hopkins MP, Reid GC, Vettrano I, Morley GW. Squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva: prognostic factors influencing survival. Gyncologic Oncology. 1991;43:113-117.

Hussain SK, Madeleine MM, Johnson LG, et al. Cervical and vulvar cancer risk in relation to the joint effects of cigarette smoking and genetic variation in interleukin 2. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention. 2008;17:1790-1799.

Iversen T, Aas M. Lymph drainage from the vulva. Gynecologic Oncology. 1983;16:179-189.

Jones RW, Baranyai J, Stables S. Trends in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva: the influence of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1997;90:448-452.

Katz A, Eifel PJ, Jhingran A, Levenback CF. The role of radiation therapy in preventing regional recurrences of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 2003;57:409-418.

Kelley JL3rd, Burke TW, Tornos C, et al. Minimally invasive vulvar carcinoma: an indication for conservative surgical therapy. Gynecologic Oncology. 1992;44:240-244.

Kelly J. Malignant disease of the vulva. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the British Commonwealth. 1972;79:265-272.

Kirkbride P, Fyles A, Rawlings GA, Manchul L, Levin W, Murphy KJ, Simm J. Carcinoma of the vagina — experience at the Princess Margaret Hospital (1974–1989). Gynecologic Oncology. 1995;56:435-443.

Kirkwood JM, Ibrahim JG, Sosman JA, et al. High-dose interferon alfa-2b significantly prolongs relapse-free and overall survival compared with the GM2-KLH/QS-21 vaccine in patients with resected stage IIB–III melanoma: results of intergroup trial E1694/S9512/C509801. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2001;19:2370-2380.

Levenback C, Coleman RL, Burke TW, Bodurka-Bevers D, Wolf JK, Gershenson DM. Intraoperative lymphatic mapping and sentinel node identification with blue dye in patients with vulvar cancer. Gynecologic Oncology. 2001;83:276-281.

Lingard D, Free K, Wright, Battistutta D. Invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva: behaviour and results in the light of changing management regimens. A review of clinicohistological features predictive of regional lymph node involvement and local recurrence. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1992;32:137-145.

MacLean AB, Reid WM. Benign and premalignant disease of the vulva. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1995;102:359-363.

MacLean AB, Makwana M, Ellis PE, Cunnington F. The management of Paget’s disease of the vulva. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2004;24:124-128.

Magrina JF, Webb MJ, Gaffey TA, Symmonds RE. Stage I squamous cell cancer of the vulva. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1979;15:453-459.

Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen sclerosus. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1995;32:393-416.

Monaghan JM. Management of Vulval Carcinoma in Clinical Gynaecological Oncology. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1990. p 145

Montana GS, Thomas GM, Moore DH, et al. Preoperative chemo-radiation for carcinoma of the vulva with N2/N3 nodes: a gynecologic oncology group study. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 2000;48:1007-1013.

Moore DH, Thomas GM, Montana GS, Saxer A, Gallup DG, Olt G. Preoperative chemoradiation for advanced vulver cancer: a phase II study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 1998;42:79-85.

Moore RG, DePasquale SE, Steinhoff MM, et al. Sentinel node identification and the ability to detect metastatic tumor to inguinal lymph nodes in squamous cell cancer of the vulva. Gynecologic Oncology. 2003;89:475-479.

Morrow CP, Curtin JP, Townsend DE. Tumour of the vulva. In Synopsis of Gynaecologic Oncology, 4th edn, New York: Wiley; 1993:65-92.

Mulayim N, Foster Silver D, Tolgay Ocal I, Babalola E. Vulvar basal cell carcinoma: two unusual presentations and review of the literature. Gynecologic Oncology. 2002;85:532-537.

Nasu K, Kawano Y, Takai N, Kashima K, Miyakawa I. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of Bartholin’s gland. Case report with review of the literature. Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation. 2005;59:54-58.

Office of National Statistics 2008 Cancer Statistics Registration, Registration of Cancer Diagnosed in 2005, England. Series MB1 No. 36. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, London.

Parikh JH, Barton DP, Ind TE, Sohaib SA. MR imaging features of vaginal malignancies. Radiographics. 2008;28:49-63.

Perez CA, Grigsby PW, Chao C, et al. Irradiation in carcinoma of the vulva: factors affecting outcome. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 1998;42:335-344.

Perez CA, Grigsby PW, Garipagaoglu M, Mutch DG, Lockett MA. Factors affecting long-term outcome of irradiation in carcinoma of the vagina. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 1999;44:37-45.

Peters WA3rd, Kumar NB, Morley GW. Carcinoma of the vagina. Factors influencing treatment outcome. Cancer. 1985;55:892-897.

Phillips GL, Bundy BN, Okagaki T, Kucera PR, Stehman FB. Malignant melanoma of the vulva treated by radical hemivulvectomy. A prospective study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Cancer. 1994;73:2626-2632.

Pingley S, Shrivastava SK, Sarin R, et al. Primary carcinoma of the vagina: Tata Memorial Hospital experience. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 2000;46:101-108.

Piura B, Gemer O, Rabinovich A, Yanai-Inbar I. Primary breast carcinoma of the vulva: case report and review of literature. European Journal of Gynaecological Oncology. 2002;23:21-24.

Piura B. Management of primary melanoma of the female urogenital tract. The Lancet Oncology. 2008;9:973-981.

Podratz KC, Symmonds RE, Taylor WF, Williams TJ. Carcinoma of the vulva: analysis of treatment and survival. Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1983;61:63-74.

Podratz KC, Gaffey TA, Symmonds RE, Johansen KL, O’Brien PC. Melanoma of the vulva: an update. Gynecologic Oncology. 1983;16:153-168.

Pride GL, Schultz AE, Chuprevich TW, Buchler DA. Primary invasive squamous carcinoma of the vagina. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1979;53:218-225.

Ragnarsson-Olding B, Johansson H, Rutqvist LE, Ringborg U. Malignant melanoma of the vulva and vagina. Trends in incidence, age distribution, and long-term survival among 245 consecutive cases in Sweden 1960–1984. Cancer. 1993;71:1893-1897.

Ragnarsson-Olding BK, Kanter-Lewensohn LR, Lagerlöf B, Nilsson BR, Ringborg UK. Malignant melanoma of the vulva in a nationwide, 25-year study of 219 Swedish females: clinical observations and histopathologic features. Cancer. 1999;86:1273-1284.

Ragnarsson-Olding BK, Nilsson BR, Kanter-Lewensohn LR, Lagerlöf B, Ringborg UK. Malignant melanoma of the vulva in a nationwide, 25-year study of 219 Swedish females: predictors of survival. Cancer. 1999;86:1285-1293.

Reid GC, Schmidt RW, Roberts JA, Hopkins MP, Barrett RJ, Morley GW. Primary melanoma of the vagina: a clinicopathologic analysis. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1989;74:190-199.

Rose PG, Piver MS, Tsukada Y, Lau T. Conservative therapy for melanoma of the vulva. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1988;159:52-55.

Rose PG. Skin bridge recurrences in vulvar cancer: frequency and management. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 1999;9:508-511.

Rouzier R, Haddad B, Plantier F, Dubois P, Pelisse M, Paniel BJ. Local relapse in patients treated for squamous cell vulvar carcinoma: incidence and prognostic value. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2002;100:1159-1167.

Sedlis A, Homesley H, Bundy BN, et al. Positive groin lymph nodes in superficial squamous cell vulvar cancer. A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1987;156:1159-1164.

Selman TJ, Luesley DM, Acheson N, Khan KS, Mann CH. A systematic review of the accuracy of diagnostic tests for inguinal lymph node status in vulvar cancer. Gynecologic Oncology. 2005;99:206-214.

Shimizu Y, Hasumi K, Masubuchi K. Effective chemotherapy consisting of bleomycin, vincristine, mitomycin C, and cisplatin (BOMP) for a patient with inoperable vulvar cancer. Gynecologic Oncology. 1990;36:423-427.

Siu SSN, Lo KWK, Chan ABW, Yu MY, Cheung TH. Nodal detection in malignant melanoma of vagina using laparoscopic ultrasonography. Gynecologic Oncology. 2004;92:985-988.

Sliutz G, Reinthaller A, Lantzsch T, et al. Lymphatic mapping of sentinel nodes in early vulvar cancer. Gynecologic Oncology. 2002;84:449-452.

Stehman FB, Bundy BN, Dvoretsky PM, Creasman WT. Early stage I carcinoma of the vulva treated with ipsilateral superficial inguinal lymphadenectomy and modified radical hemivulvectomy: a prospective study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1992;79:490-497.

Stehman FB, Bundy BN, Thomas G, et al. Groin dissection versus groin radiation in carcinoma of the vulva: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 1992;24:389-396.

Stock RG, Chen AS, Seski J. A 30-year experience in the management of primary carcinoma of the vagina: analysis of prognostic factors and treatment modalities. Gynecologic Oncology. 1995;56:45-52.

Sutton GP, Miser MR, Stehman FB, Look KY, Ehrilich CE. Trends in the operative management of invasive squamous carcinoma of the vulva at Indiana University, 1974 to 1988. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1991;164:1472-1478.

Tarraza HMJr, Meltzer SE, DeCain M, Jones MA. Vaginal metastases from renal cell carcinoma: report of four cases and review of the literature. European Journal of Gynaecological Oncology. 1998;19:14-18.

Tasseron EW, van der Esch EP, Hart AA, Brutel de la Rivière G, Aartsen EJ. A clinicopathological study of 30 melanomas of the vulva. Gynecologic Oncology. 1992;46:170-175.

Taussig FJ. Cancer of the vulva — an analysis of 155 cases (1911–1940). American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1940;40:764-779.

Thomas G, Dembo A, DePetrillo A, et al. Concurrent radiation and chemotherapy in vulvar carcinoma. Gynecologic Oncology. 1989;34:263-267.

Thomas GM, Dembo AJ, Bryson SC, Osborne R, DePetrillo AD. Changing concepts in the management of vulvar cancer. Gynecological Oncology. 1991;42:9-21.

van der Avoort IA, Shirango H, Hoevenaars BM, et al. Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma is a multifactorial disease following two separate and independent pathways. International Journal of Gynecological Pathology. 2006;25:22-29.

van der Velden J, van Lindert AC, Lammes FB, et al. Extracapsular growth of lymph node metastases in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. The impact on recurrence and survival. Cancer. 1995;75:2885-2890.

van der Velden J 1996 Some Aspects of the Management of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Vulva. Thesis. Amsterdam.

van Doorn HC, Ansink A, Verhaar-Langereis M, Stalpers L 2006 Neoadjuvant chemoradiation for advanced primary vulvar cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 3: CD003752.

van der Zee AG, Oonk MH, de Hullu JA, et al. Sentinel node dissection is safe in the treatment of early-stage vulvar cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:884-889.

Verschraegen CF, Benjapibal M, Supakarapongkul W, et al. Vulvar melanoma at the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center: 25 years later. International Journal of Gynecological. Cancer. 2001;11:359-364.

Way S. Carcinoma of the vulva. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1960;79:692-697.

Willis RA. The Spread of Tumours in the Human Body, 3rd edn. London: Butterworth; 1973.