CHAPTER 66 Macular hole surgery

Introduction

Macular hole (MH) was an incurable condition until the late 1980s, when its first successful surgical treatment was reported1. Since then it has aroused ophthalmologists’ interest, which has led to improved understanding of its pathogenesis, surgical treatment, and postoperative results.

History

MH was first described by Knapp in 1869. In 1924, Lister considered the role of the vitreous in the occurrence of MHs by describing vitreous bands causing traction on the macula, but this hypothesis was ignored for a long time. Gass in 1988 postulated that focal shrinkage of the prefoveolar vitreous cortex and tangential retinal traction are responsible for MH formation2. Finally in 1999 Gaudric et al. and Haouchine et al., using optical coherence tomography (OCT), provided a precise description of the formation of MHs3,4.

Epidemiologic consideration and terminology

The onset of idiopathic MH usually occurs in the 6th decade of life, predominantly among women. Both eyes are affected in 10% of cases. Population studies has found an incidence of idiopathic MH of 7.8 per 100 000 persons per year, with a female to male ratio of 3.3 to 1 and a prevalence of 0.33% in elderly subjects over 55 years old5,6.

Clinical features, diagnosis, and differential diagnosis

Diagnosis of an idiopathic full-thickness MH

Most MHs occur in eyes with no previous pathology (‘idiopathic’). The patient generally complains of acute or subacute decrease in both far and near visual acuity (VA), ± metamorphopsia and/or micropsia, ± positive or negative scotoma. Five percent of patients are asymptomatic7. The visual loss caused by MH is variable. VA decreases gradually with time, and after several months of evolution it is usually around 0.1. In a series of unoperated MHs, more than 80% of eyes had a VA between 0.1 and 0.05 after 5 years of follow-up8. In practice, the VA of an eye with a full-thickness MH is usually less than 0.5 (typically 0.2). Patients rarely identify a central scotoma, but fairly frequently report what is indicative of a negative microscotoma (i.e. the disappearance of a letter from a word). The distortion or constriction of images and words is also reported.

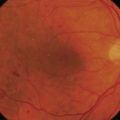

At fundus biomicroscopy, the MH appears as a round full-thickness defect with sharp edges located at the center of the fovea. The size of the hole varies and tends to increase with time8–10. The surrounding retina is usually thickened by edema and microcysts, and is slightly detached from the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). In half the cases, 1–15 yellow deposits are present on the exposed RPE. An operculum may also be found in front of the hole. It is generally smaller than the hole, usually round but sometimes irregular in shape, translucent, discreetly yellow, and slightly mobile with eye movements. An epiretinal membrane may also be present around the hole. It appears as a discreet reflection, usually with no wrinkling of the internal limiting membrane (ILM). The prevalence of epiretinal membranes is higher in long-standing MHs11–13. Posterior vitreous detachment may vary, from incomplete separation of the vitreous from the macula to a vitreous completely detached from the macula and even from the disc3,4.

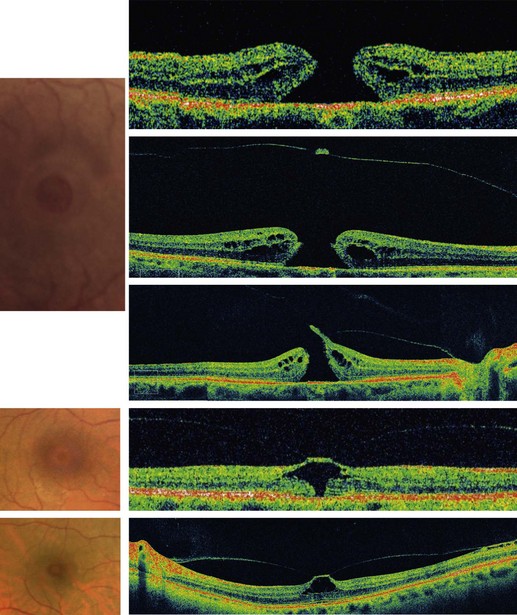

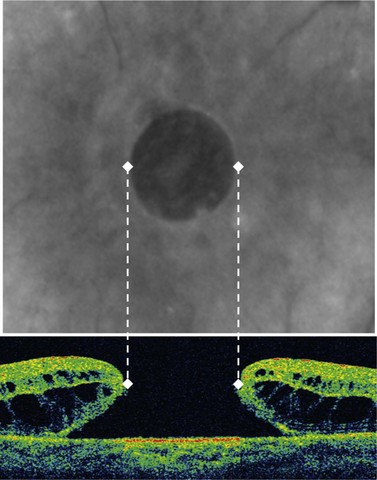

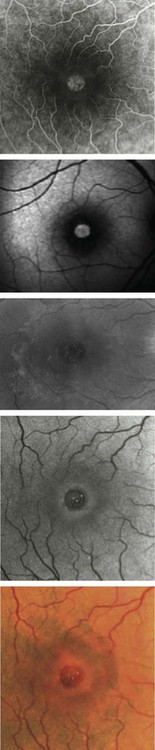

OCT allows a reliable diagnosis of MHs by confirming the existence of a full-thickness opening in the center of the fovea with no interposition of tissue between the vitreous cavity and the RPE. OCT also clearly differentiates full-thickness MHs from lamellar or pseudo-holes, shows the stage of MH, measures its diameter, and provides information regarding the risk of developing a MH in the fellow eye. No other ancillary testing is mandatory. Fundus photographs can be used as archive. Fundus autofluorescence images and fluorescein angiography are not of great interest for MHs. The defect is usually hyperautofluorescent and after fluorescein injection shows a discrete early hyperfluorescence. The surface area of fluorescence does not increase during angiography and its intensity decreases at later phases with no dye diffusion (Fig. 66.1)14,15.

Differential diagnosis

Without OCT, MHs might be misdiagnosed. With OCT, the differential diagnosis is very reliable. Unlike a full-thickness MH, in a macular lamellar or pseudohole there is an interposition of retinal tissue between the vitreous cavity and RPE on OCT scans. Lamellar holes, usually due to an aborted process of MH formation, are characterized by thinning of the base of the foveal center, and normal thickness of the foveal edge that presents a cleft between its inner and outer retina16. Pseudoholes are due to tangential retraction of an epiretinal membrane that thickens the foveal edge with a normal or thin foveal center16.

Impending MHs

In most cases, early stage MHs are foveal cysts3,4. VA in these cases is usually normal or above 0.5. The macula may look normal on fundus biomicroscopy, or else an outer central yellow spot may be present, combined with a flattened foveal pit and foveolar radial striae17. In more advanced cases, outer MHs, the foveola has a cystic appearance, with radial striae. An outer yellow ring is present17.

Secondary MHs

Post-traumatic MHs mostly occur in young males. Traumatic MH is due to a violent deformation of the eyeball, which results in rupture of the fovea18,19. The vitreous remains completely attached to the retinal surface. The profile of the traumatic hole is not different from that of the idiopathic hole, except in cases in which the retina is thinner than normal at the hole edge due to post-traumatic atrophy of the pigment epithelium. Indeed, in some cases, these MH may be associated with a break in Bruch’s membrane or an area of pigment epithelium atrophy at the posterior pole, which on OCT scans corresponds to retinal thinning and to a deep scotoma in the visual field. If the lesion involves the foveal center, there is a risk that vision will not improve, even if the MH is closed.

In about 10% of highly myopic eyes, OCT reveals the presence of a MH in the staphyloma, which causes moderate loss of vision and is not seen on biomicroscopy. In eyes with high myopia, an MH may also occur after a long evolution of a myopic foveoschisis, especially when it is complicated by foveal detachment20.

Anatomical considerations

Before OCT became available, Gass classified MHs into several stages on the basis of fundus biomicrospy. Later he revised his classification. This revised classification is still in use and is summarized in Box 66.1. Mainly on the basis of OCT examination of MHs and their relationship with posterior vitreous detachment, Gaudric et al. and Haouchine et al. gave the description of the different steps in MH formation and evolution (Fig. 66.2)3,4. Gaudric’s description of MHs is also used as a system of classification mainly based on OCT. In this classification the size of the MH is indicated separately. The information provided by Gaudric’s classification is more accurate.

Box 66.1

Gass’s revised classification of macular holes

Fundamental principles

Since the first description of MH surgery, the surgical technique is based on vitrectomy with posterior vitreous detachment, peeling of any epimacular membrane, thorough fluid–gas exchange, and postoperative face-down positioning of the patient1,21. However, many variants of this technique have been proposed. The use of several adjuvants, including TGFβ2, autologous serum, or autologous platelets, has been proposed to increase the success rate, without becoming widespread22,23. The peeling of the ILM has become popular for the same purpose, especially since it has been facilitated with the use of visualizing agents, even without being proved useful for all MH (Clip 8.5). Different types of tamponade are now used and the dogma of face-down positioning for all MHs is challenged.

The role of gas tamponade is to create contact of the gas bubble with the macula rapidly resulting in the flattening of the edematous edge of the hole, and the mechanical narrowing of the foveal defect. The necessary duration of the tamponade depends on the duration of the following healing process, which requires glial cell proliferation resulting in the formation of a small central foveal scar. The duration of this healing process seems to be different, depending on the size of the hole, varying from a few days to a few weeks24.

Goals of surgery

The goal of MH surgery is to increase VA by closing the MH, i.e. by reducing its size as much as possible by flattening its edges and creating a small glial scar that fills the remaining gap and supports the center of the fovea25–27.

Indications for surgery

Idiopathic full-thickness MHs usually remain open if they are not treated and cause great visual impairment after several years (VA between 0.1 and 0.05 in more than 80% of cases)8. They constitute an indication for surgery.

Rarely, very small holes (especially those with a diameter ≤250 µm) may close within a few weeks without surgery, even if the vitreous cortex is already detached28. Surgery for these very small MHs may therefore be delayed until up to 3 months after their appearance, to give them a chance to close spontaneously.

Very large MHs, usually long-standing holes, are considered to have a poor prognosis. However, in a series of selected very large MHs (>800 µm in diameter), the postoperative closure rate was reported to be higher than 70%, with an increase in the mean VA of closed holes (Surgical outcome of extra-large MHs. R. Tadayoni, M. Bennani, A. Gaudric, AAO 2007). Selected cases of very large MHs with no significant pigment epithelium alteration, even if they are long standing, may also benefit from surgery29,30.

Traumatic MHs may close spontaneously in the first few months. Observation during this period may therefore be the preferred choice in the management of traumatic MHs31,32. If such holes are still open after this period, surgery can close them in most cases. In myopic eyes, many of the MHs incidentally detected by OCT are asymptomatic and do not need surgery. Symptomatic holes can benefit from surgery. MHs secondary to central retinal atrophy of various etiologies have a poor postoperative prognosis and may not constitute good indications for surgery.

Preoperative assessment

Preoperative assessment of a patient presenting with a MH includes a complete examination of both eyes including fundus biomicroscopy and also OCT examination of the macula and posterior hyaloid. Of particular interest are: whether the vitreous is completely detached (Weiss’s ring), size of the MH (Fig. 66.3), and the possible presence of an epiretinal membrane.

Examination of the fellow eye provides information about their risk of a MH, which is around 10%. Fellow eyes whose posterior hyaloid is already detached from the macular area are not at risk for developing a MH, even if the hyaloid remains attached to the optic disc and the periphery of the posterior pole33. OCT makes it possible to diagnose such premacular posterior vitreous detachment, which cannot be detected by biomicroscopy alone. When, on the other hand, part of the posterior hyaloid remains attached to the foveal center, the risk of MH remains34. However, in some cases, spectral domain (SD) OCT shows very subtle changes in the shape of the foveal pit at the junction between the posterior hyaloid and the ILM, due to vitreous traction. In individuals whose fellow eyes already exhibit an MH, this may constitute a risk of MH.

Operation techniques

Peeling

In about 30% of cases there is an epiretinal membrane around the hole. Membranes are more frequent in stage 4 and large MHs11,35. They are not contractile like idiopathic epiretinal membranes: they are composed of vitreous collagen and a few cellular elements, especially fibroblasts. As they are soft and friable, it is easier to remove them, for example by gently brushing the retinal surface from the outside to the MH edge, with either the soft tip of a back-flush cannula or with a soft retinal scraper, rather than trying to remove them with forceps. These membranes often adhere firmly to the hole edge, in which case they can be cut with the vitreous probe.

ILM peeling is currently performed in MH surgery, although one should bear in mind that at least 80% of all MHs and about 95% of small MHs (up to 400 µm in diameter) can be closed without ILM peeling36,37. Discrete damage to the nerve fiber layer and small but asymptomatic paracentral scotomata detected during microperimetry after MH surgery with ILM peeling have been reported38,39. For small MHs, ILM peeling is not mandatory36. However, several studies suggest that ILM peeling increases the success rate of MH surgery, at least for large MHs (>400 µm) (Internal limiting membrane peeling for large macular holes: a randomized, multicentric, and controlled clinical trial. R. Tadayoni R et al. ARVO 2009)36,40,41. Several techniques, using forceps or scrapers, are used to peel the ILM. Peeling usually begins a small distance away from the hole edge, where the ILM is thicker and less adherent. It is then dissected about 1 mm all round the hole (see also Clip 8.5).

Intraoperative complications

The most common intraoperative complication of MH surgery is an iatrogenic retinal break. Despite continuous progress in vitrectomy techniques, this risk has not been re-evaluated since the 1990s, when it was found to be around 5%42,43. It warrants careful examination of the retinal periphery before the injection of gas, in order to detect and treat any breaks.

Postoperative care

For the patient, the most difficult part of MH surgery is the postoperative positioning. There is no consensus about the duration of face-down positioning. The most common practice is to encourage the patient to remain face-down, as much as possible for 1 week. Several proposals have been made to ease this positioning. However, only two randomized series have so far been carried out in this respect. One showed a significant reduction of the success rate without face-down positioning, but a post hoc analysis of this study suggested that the reduction was significant only for MH > 400 µm and not in smaller holes44. The other study, which only considered only idiopathic MHs ≤400 µm in diameter, demonstrated that after surgery for these small MHs a strategy that did not impose the face-down positioning was not inferior to face-down positioning (confidence interval for closure rate reduction: 0 to 14.88%, with a 5% risk of error)37. In this study, the patient had a large (>90%) bubble of C2F6 and avoided the supine position for 10 days. The results may not apply to patients treated with a small volume of non-lasting postoperative bubble gases or to patients with full freedom of positioning, including the supine position. Consequently, depending on the size of the hole, and the surgical technique (in particular, the type of gas used, and the actual size of the bubble), one can choose from different strategies, taking into account on the one hand the painfulness of face-down positioning (and also a small risk of complications like thrombophlebitis and pulmonary embolism or ulnar nerve palsies) and, on the other hand, the need to tamponade the fovea during the time necessary for a scar to form in a closed MH.

Postoperative complications

The most serious postoperative complication is retinal detachment, which may occur within days or weeks after the operation. Estimates of its frequency vary from 1 to 14%21,43. Today, with better fluidics and operational precautions, the rate of retinal detachment should remain below 3%. However, it remains mandatory to detect these detachments carefully as soon as possible as the gas bubble prevents some patients from noticing visual symptoms.

The occurrence of a cataract after MH surgery is common45,46. Patients should be aware that, in most cases, cataract surgery becomes necessary 1–2 years after MH surgery. For some surgeons this justifies combining MH surgery with cataract surgery at the same operating time.

Reopening of the MH may occur up to more than 6 years after surgery. However, most reopenings occur during the first 2 years (approximately the mean and median values for the time from surgery to reopening)47. Rates of reopening vary considerably in the literature, from 0 to 25%, with a mean of about 6%. The real cause of reopening is still not known. Recently, its incidence seems to have decreased, corresponding to a concomitant increase in the success rate of MH surgery. Some authors believe this is connected with the improvement in surgery, including ILM peeling47,48. A reopened MH can be operated on in the same way as for initial surgery, with similar positive results49.

1 Kelly NE, Wendel RT. Vitreous surgery for idiopathic macular holes. Results of a pilot study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109(5):654-659.

2 Ho AC, Guyer DR, Fine SL. Macular hole. Surv Ophthalmol. 1998;42(5):393-416.

3 Gaudric A, Haouchine B, Massin P, et al. Macular hole formation: new data provided by optical coherence tomography. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117(6):744-751.

4 Haouchine B, Massin P, Gaudric A. Foveal pseudocyst as the first step in macular hole formation: a prospective study by optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(1):15-22.

5 Aaberg TM, Blair CJ, Gass JDM. Macular holes. Am J Ophthalmol. 1970;69(4):555-562.

6 Bronstein MA, Trempe CL, Freeman H. Fellow eyes of eyes with Macular Holes. Am J Ophthalmol. 1981;92(6):757-761.

7 Morgan CM, Schatz H. Idiopathic macular holes. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;99(4):437-444.

8 Casuso LA, Scott IU, Flynn HWJr, et al. Long-term follow-up of unoperated macular holes. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(6):1150-1155.

9 Chew EY, Sperduto RD, Hiller R, et al. Clinical course of macular holes: the Eye Disease Case-Control Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117(2):242-246.

10 Hikichi T, Yoshida A, Akiba J, et al. Natural outcomes of stage 1, 2, 3, and 4 idiopathic macular holes. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79(6):517-520.

11 Blain P, Paques M, Massin P, et al. Epiretinal membranes surrounding idiopathic macular holes. Retina. 1998;18(4):316-321.

12 Cheng L, Freeman WR, Ozerdem U, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and natural history of epiretinal membranes surrounding idiopathic macular holes. Virectomy for Macular Hole Study Group. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(5):853-859.

13 Kim JW, Freeman WR, el-Haig W, et al. Baseline characteristics, natural history, and risk factors to progression in eyes with stage 2 macular holes. Results from a prospective randomized clinical trial. Vitrectomy for Macular Hole Study Group. Ophthalmology. 1995;102(12):1818-1828. discussion 28–9

14 Gass JDM. Idiopathic senile macular hole. Retina and VitreousRM FranklinEdAmsterdamNew YorkKugler, 1993.

15 Gass JDM, 3rd edn. Stereoscopic Atlas of Macular diseases: Diagnosis and Treatment, vol. 2. St Louis: CV Mosby; 1987.

16 Haouchine B, Massin P, Tadayoni R, et al. Diagnosis of macular pseudoholes and lamellar macular holes by optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138(5):732-739.

17 Gass JD. Reappraisal of biomicroscopic classification of stages of development of a macular hole. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;119(6):752-759.

18 Oehrens AM, Stalmans P. Optical coherence tomographic documentation of the formation of a traumatic macular hole. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142(5):866-869.

19 Johnson RN, McDonald HR, Lewis H, et al. Traumatic macular hole: observations, pathogenesis, and results of vitrectomy surgery. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(5):853-857.

20 Coppe AM, Ripandelli G, Parisi V, et al. Prevalence of asymptomatic macular holes in highly myopic eyes. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(12):2103-2109.

21 Wendel RT, Patel AC, Kelly NE, et al. Vitreous surgery for macular holes. Ophthalmology. 1993;100(11):1671-1676.

22 Gaudric A, Massin P, Paques M, et al. Autologous platelet concentrate for the treatment of full-thickness macular holes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1995;233(9):549-554.

23 Paques M, Chastang C, Mathis A, et al. Effect of autologous platelet concentrate in surgery for idiopathic macular hole: results of a multicenter, double-masked, randomized trial. Platelets in Macular Hole Surgery Group. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(5):932-938.

24 Yamana T, Kita M, Ozaki S, et al. The process of closure of experimental retinal holes in rabbit eyes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2000;238(1):81-87.

25 Rosa RHJr, Glaser BM, de la Cruz Z, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of an untreated macular hole and a macular hole treated by vitrectomy, transforming growth factor-beta 2, and gas tamponade. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;122(6):853-863.

26 Madreperla SA, Geiger GL, Funata M, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of a macular hole treated by cortical vitreous peeling and gas tamponade. Ophthalmology. 1994;101(4):682-686.

27 Funata M, Wendel RT, Green WR. Clinicopathologic study of bilateral macular holes treated with pars plana vitrectomy and gas tamponade. Retina. 1992;12(4):289-298.

28 Privat E, Tadayoni R, Gaucher D, et al. Residual defect in the foveal photoreceptor layer detected by optical coherence tomography in eyes with spontaneously closed macular holes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143(5):814-819.

29 Stec LA, Ross RD, Williams GA, et al. Vitrectomy for chronic macular holes. Retina. 2004;24(3):341-347.

30 Haritoglou C, Neubauer AS, Gandorfer A, et al. Indocyanine green for successful repair of a long-standing macular hole. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136(2):389-391.

31 Kusaka S, Fujikado T, Ikeda T, et al. Spontaneous disappearance of traumatic macular holes in young patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;123(6):837-839.

32 Yamashita T, Uemara A, Uchino E, et al. Spontaneous closure of traumatic macular hole. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133(2):230-235.

33 Chan A, Duker JS, Schuman JS, et al. Stage 0 macular holes: observations by optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(11):2027-2032.

34 Uchino E, Uemura A, Ohba N. Initial stages of posterior vitreous detachment in healthy eyes of older persons evaluated by optical coherence tomography. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(10):1475-1479.

35 Kurihara K, Ishibashi T, Oshima K. The residual epiretinal membrane after vitrectomy for macular hole. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1999;237(8):648-653.

36 Tadayoni R, Gaudric A, Haouchine B, et al. Relationship between macular hole size and the potential benefit of internal limiting membrane peeling. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(10):1239-1241.

37 Tadayoni R, Vicaut E, Devin F, et al. A randomized controlled trial of alleviated positioning after small macular hole surgery. Ophthalmology. 2011 Jan;118(1):150-155. Epub 2010 Oct 29

38 Tadayoni R, Paques M, Massin P, et al. Dissociated optic nerve fiber layer appearance of the fundus after idiopathic epiretinal membrane removal. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(12):2279-2283.

39 Haritoglou C, Ehrt O, Gass CA, et al. Paracentral scotomata: a new finding after vitrectomy for idiopathic macular hole. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85(2):231-233.

40 Christensen UC, Kroyer K, Sander B, et al. Value of internal limiting membrane peeling in surgery for idiopathic macular hole stage 2 and 3: a randomised clinical trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93(8):1005-1015.

41 Kwok AK, Lai TY, Wong VW. Idiopathic macular hole surgery in Chinese patients: a randomised study to compare indocyanine green-assisted internal limiting membrane peeling with no internal limiting membrane peeling. Hong Kong Med J. 2005;11(4):259-266.

42 Sjaarda RN, Glaser BM, Thompson JT, et al. Distribution of iatrogenic retinal breaks in macular hole surgery. Ophthalmology. 1995;102(9):1387-1392.

43 Park SS, Marcus DM, Duker JS, et al. Posterior segment complications after vitrectomy for macular hole. Ophthalmology. 1995;102(5):775-781.

44 Guillaubey A, Malvitte L, Lafontaine PO, et al. Comparison of face-down and seated position after idiopathic macular hole surgery: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146(1):128-134.

45 Ogura Y, Shahidi M, Mori MT, et al. Improved visualization of macular hole lesions with laser biomicroscopy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109(7):957-961.

46 Thompson JT, Glaser BM, Sjaarda RN, et al. Progression of nuclear sclerosis and long-term visual results of vitrectomy with transforming growth factor beta-2 for macular holes. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;119(1):48-54.

47 Kumagai K, Furukawa M, Ogino N, et al. Incidence and factors related to macular hole reopening. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149(1):127-132.

48 Passemard M, Yakoubi Y, Muselier A, et al. Long-term outcome of idiopathic macular hole surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149(1):120-126.

49 Valldeperas X, Wong D. Is it worth reoperating on macular holes? Ophthalmology. 2008;115(1):158-163.