33

Lupus Erythematosus

General

• A multisystem AI-CTD disorder that prominently affects the skin.

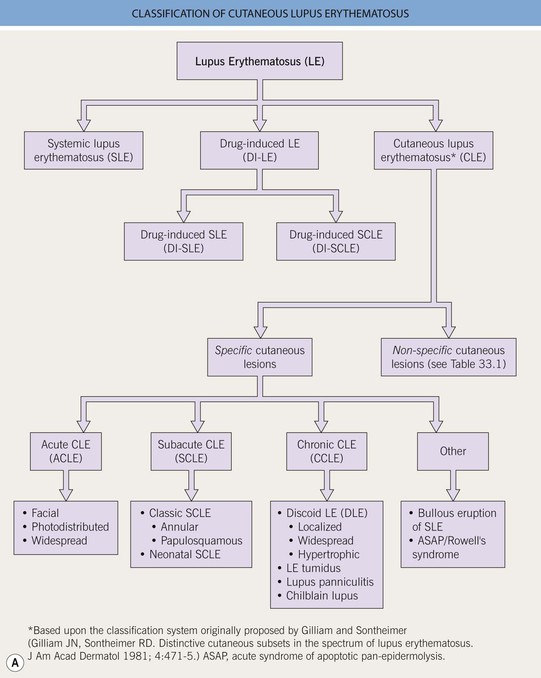

• Broadly divided into systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE), and drug-induced lupus erythematosus (DI-LE) (Fig. 33.1).

Fig. 33.1 Classification of cutaneous lupus erythematosus (LE). A Spectrum of LE. B Major forms of cutaneous LE.

• CLE is further classified into specific and nonspecific skin lesions, based on the histopathologic presence (specific) or absence (nonspecific, Table 33.1) of an ‘interface dermatitis’; however, this is not a perfect classification scheme because some specific entities (e.g. LE tumidus, lupus panniculitis) do not demonstrate an ‘interface dermatitis’ and other, non-lupus entities may display an ‘interface dermatitis’ on histopathology (e.g. dermatomyositis).

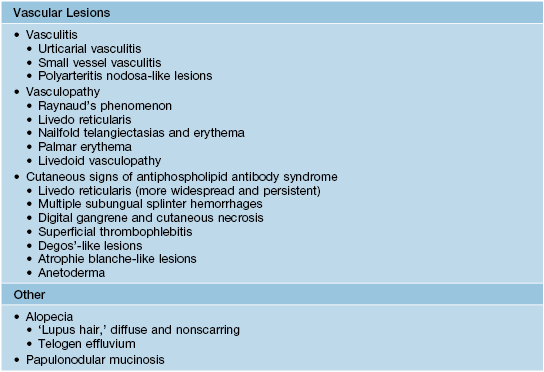

Table 33.1

Cutaneous findings (nonspecific) that suggest the diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus.

These cutaneous lesions are associated with LE but are not specific to LE itself. The presence of nonspecific LE skin lesions raises the possibility of SLE and may signify more significant internal disease. The presence of these nonspecific lesions should prompt an evaluation for SLE (see Tables 33.2 and 33.3).

• Classically, the three major forms of specific skin lesions are chronic cutaneous LE (CCLE), subacute cutaneous LE (SCLE), and acute cutaneous LE (ACLE), with CCLE being subdivided into four different entities (see Fig. 33.1).

• Once a diagnosis of CLE is made, initial and longitudinal evaluation for systemic manifestations of SLE is recommended (Tables 33.2–33.4).

Table 33.2

The American College of Rheumatology 1982 revised criteria for classification of systemic lupus erythematosus.*

Although these criteria are very helpful in distinguishing SLE from other rheumatologic conditions, they are not very helpful in distinguishing other skin diseases from LE. See Appendix for 2012 Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for SLE.

| Criterion | Basic Definition |

| 1. Malar rash | Fixed erythema, flat or raised over malar eminences |

| 2. Discoid rash | Typical DLE lesions |

| 3. Photosensitivity | Skin rash due to an unusual reaction to sunlight |

| 4. Oral ulcers | Oral or nasal ulceration, observed by a physician |

| 5. Arthritis | Non-erosive, involving ≥2 peripheral joints |

| 6. Serositis | Pleuritis or pericarditis |

| 7. Renal disorder | Persistent proteinuria or cellular casts |

| 8. Neurologic disorder | Seizures or psychosis |

| 9. Hematologic disorder | Hemolytic anemia or leukopenia or thrombocytopenia |

| 10. Immunologic disorder | Anti-dsDNA or anti-Sm or antiphospholipid antibodies |

| 11. Antinuclear antibody | Abnormal ANA titer, in the absence of drug-induced SLE |

* The proposed classification is based on 11 criteria. For the purpose of identifying patients in clinical studies, a person shall be said to have SLE if any 4 or more of the 11 criteria are present, serially or simultaneously, during any interval of observation.

DLE, discoid lupus erythematosus.

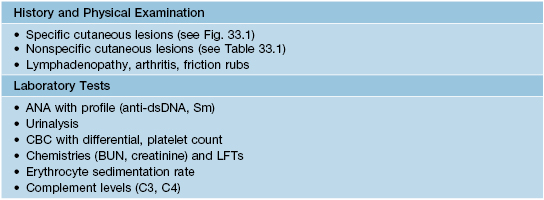

Table 33.3

Evaluation for systemic lupus erythematosus.

ANA, antinuclear antibodies; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CBC, complete blood count; ds, double-stranded; LFTs, liver function tests; Sm, Smith.

Table 33.4

Different forms of cutaneous lupus and their associations with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

| Type of Cutaneous Lupus | Association with SLE |

| • Acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (ACLE) | ++++ |

| • Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) | ++ |

| • Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE) | |

| • Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE*) | |

| – Localized (head and neck) | + |

| – Widespread/disseminated | ++ |

| – Hypertrophic | + |

| • Lupus erythematosus tumidus (LET) | +/– |

| • Lupus panniculitis | + |

| • Chilblain lupus | ++ |

| • Other variants | |

| • Bullous eruption of SLE | ++++ |

| • Rowell’s syndrome | ++ to ++++ |

* Risk factors for the development of SLE include widespread DLE, arthralgias/arthritis, anemia, leukopenia, increased ESR, and higher ANA titers.

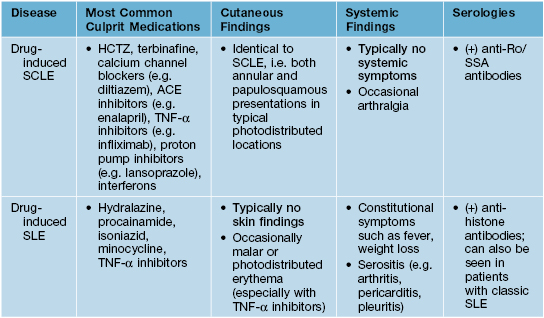

• Before making a definitive diagnosis of cutaneous lupus, it is necessary to exclude a drug-induced etiology (Table 33.5).

Table 33.5

Classic distinctions between drug-induced SCLE and drug-induced SLE.

Note that TNF-α inhibitors can cause both DI-SCLE and DI-SLE.

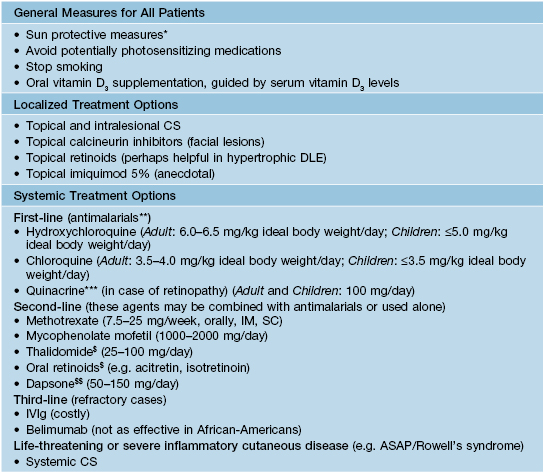

• Treatment options for the various subtypes of CLE are fairly similar (Table 33.6).

Table 33.6

Suggested therapies for cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE).

All patients should be counseled about daily sun protection, as both UVA and UVB can trigger flares of CLE and may even lead to exacerbations of systemic symptoms. Topical therapy is indicated in local disease and as an adjunct to systemic therapy in severe and widespread CLE. Systemic therapy is indicated when skin lesions are widespread, disfiguring, scarring, or refractory to topical agents, or when extracutaneous manifestations are present, e.g. arthritis.

* Broad-spectrum sunscreen, sun avoidance, sun-protective clothing.

** Delayed onset of action (4–8 weeks); earlier institution may stave off progression of CLE to SLE; recommended monitoring includes baseline and every 3–4 month CBC, LFTs, BUN/Cr, and yearly eye examinations.

*** Quinacrine can be added, as combination therapy, to either hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine.

$ Risk of teratogenicity.

$$ Exclude glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency.

DLE, discoid lupus erythematosus; IV, intravenous; CBC, complete blood count; LFTs, liver function tests; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Cr, creatinine; ASAP, acute syndrome of apoptotic pan-epidermolysis.

Drug-Induced Lupus Erythematosus

Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus: Specific Lesions

Chronic Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus (CCLE)

Discoid Lupus Erythematosus (DLE)

• Most common skin manifestation of LE; the terms CCLE and DLE are often used interchangeably, but CCLE encompasses four entities (see Fig. 33.1).

• Overall, ~5–10% of patients will go on to develop SLE (see Table 33.4), but DLE can be a presenting manifestation of SLE.

• Three clinical variants of DLE are recognized.

– Localized: Most common; involves the head and neck region; ≤5% risk of progression to SLE.

– Hypertrophic: Unusual variant; favors extensor arms > face, upper trunk (Fig. 33.2H); thick scale overlying or at periphery of DLE lesions; may resemble hypertrophic actinic keratoses, SCC, hypertrophic lichen planus, or prurigo nodularis.

Fig. 33.2 Various presentations of discoid lesions of lupus erythematosus (DLE). Lesions, which favor the head and neck region, may show erythema, scaling, atrophy, and dyspigmentation in addition to scarring (and alopecia) (A–D). The scarring process may be destructive (E). Less common sites include the palms and soles, where lesions can be keratotic or ulcerative (F, G), as seen in lichen planus. The latter patient had systemic lupus erythematosus and responded well to isotretinoin. H Occasionally, hypertrophic lesions develop within significant hyperkeratosis. I Discoid lupus lesions with vitiligo-like depigmentation. C, Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD. H, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD; I, Courtesy, Joyce Rico, MD.

• Occasionally can involve mucosal surfaces, palms and soles (see Fig. 33.2F,G).

• May occur in sun-exposed or sun-protected sites (e.g. scalp).

• Early lesions: inflamed, indurated plaques with erythema and scale.

• Well-established lesions: typically display follicular plugging, atrophy, scarring (and alopecia), and dyspigmentation (see Fig. 33.2A–E); the follicular plugging is often best appreciated in the conchal bowl of the ear.

• DDx: Early lesions: Jessner’s lymphocytic infiltrate, polymorphic light eruption (PMLE), lymphocytoma cutis, lymphoma cutis, granuloma faciale, sarcoidosis; Late lesions: lichen planus (hypertrophic, palmoplantar and mucosal variants), sarcoidosis.

• Typical Rx: high-potency topical CS, intralesional CS (5 mg/cc), and/or antimalarials (see Table 33.6).

Lupus Erythematosus (LE) Tumidus

• Most common on the face and upper trunk; reportedly <1% of patients eventually develop SLE.

• Lesions characterized by erythema, induration, and often central clearing (Fig. 33.3); scale, follicular plugging, scarring, and atrophy are absent.

Fig. 33.3 Lupus erythematosus tumidus. Annular pink plaques on the chest (A) and pink-violet plaques on the face (B). None of the lesions have epidermal change. B, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• DDx: Jessner’s lymphocytic infiltrate, PMLE, REM (chest lesions), papulonodular mucinosis.

Lupus Panniculitis (See Chapter 83)

• The most common sites of involvement are the face, upper outer arms, upper trunk, breasts, buttocks, and thighs, with the majority representing sites of abundant fat (Fig. 33.4).

Fig. 33.4 Lupus panniculitis. Erythematous plaque on the upper arm. The lesions may resolve with lipoatrophy.

• Sometimes overlying DLE lesions are seen (termed ‘lupus profundus’).

Chilblain Lupus (SLE Pernio)

• Typically presents with erythematous to dusky purple papulonodules and plaques on the toes, fingers > nose, elbows, knees, and lower legs (Fig. 33.5).

Fig. 33.5 Chilblain lupus. Violaceous plaques, some with scale, on toes. If there is a family history of this disorder, the possibility of mutations in TREX1, which encodes a DNA exonuclease, can be considered.

• With time, some lesions may progress to resemble DLE both clinically and histopathologically.

• DDx: idiopathic chilblains (following exclusion of SLE), familial chilblain lupus (TREX1 mutation), other cold-induced syndromes (see Chapter 74).

Subacute Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus (SCLE)

• Characterized by non-scarring, annular, or papulosquamous eruptions in photodistributed sites (Fig. 33.6).

Fig. 33.6 Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE). A Papulosquamous and annular lesions on the upper back; this site along with the upper, outer arms are the most common distribution patterns. B, C The margins of the annular lesions may have scale-crust (B) or be composed of multiple papules (C). D The lesions on the hands conform to the typical distribution of lupus lesions, sparing the knuckles. A, Courtesy, Kathryn Schwarzenberger, MD; B, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD; D, Courtesy, Lela Lee, MD.

• Favors the upper trunk and upper outer arms > lateral neck, forearms, hands (see Fig. 33.6).

• Interestingly, often spares the mid-face.

• Two common clinical presentations are recognized.

– Annular: raised erythematous borders with central clearing (see Fig. 33.6B, C).

– Papulosquamous: psoriasiform or eczematous appearance (see Fig. 33.6A).

• Long-term residual changes include dyspigmentation (most often hypo- to depigmentation).

• Approximately 10–15% of patients may over time develop SLE (see Table 33.4).

• Depending on the laboratory, ~70% of patients have associated anti-Ro/SSA antibodies.

• Roughly 50% of patients fulfill ≥4 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for SLE (see Table 33.2), but they rarely develop serious systemic involvement; arthralgias most common.

• DDx: Annular variant: dermatophytosis, granuloma annulare, erythema annulare centrifugum, or other annular erythemas (see Chapter 15); Papulosquamous variant: photo-lichenoid drug reaction (e.g. HCTZ, antimalarials), psoriasis, photoexacerbated eczema, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), lichen planus, PMLE.

• Before a diagnosis of classic SCLE can be made, exclude the possibility of DI-SCLE (see Table 33.5).

Neonatal SCLE (NLE)

• These infants primarily have anti-Ro/SSA antibodies (>98%), but may also have anti-La/SSB or anti-U1RNP antibodies.

• Cutaneous lesions are similar to adult SCLE but favor the face and periorbital areas and may be atrophic (Fig. 33.7).

Fig. 33.7 Neonatal lupus erythematosus (NLE). Annular erythematous plaques on the forehead and scalp. Note the resemblance to the annular form of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• Photosensitivity is common but sun exposure is not necessary for lesion formation.

Acute Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus (ACLE)

• Three clinical presentations are recognized:

– Facial (malar): the classic ‘butterfly’ eruption, presenting with symmetric erythematous patches or more infiltrated plaques over the nasal bridge and cheeks; spares nasolabial folds (Fig. 33.8A–C).

Fig. 33.8 Acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (ACLE). The facial erythema, often referred to as a ‘butterfly rash,’ may be variable (A), edematous (B), or have associated scale (C). The presence of small erosions can aid in the clinical differential diagnosis. This patient (D) had ACLE lesions on the arms as well as the face. A, Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD; B–D, Courtesy, Lela Lee, MD.

– Photodistributed: exanthematous to urticarial eruption involving primarily UV-exposed skin, e.g. upper chest, extensor arms (Fig. 33.8D), dorsal hands (with sparing of the knuckles).

Other

Bullous Eruption of SLE

• Clinically presents as blisters (ranging from tiny vesicles to large tense bullae) on an erythematous base, typically involving the face, neck, upper trunk, proximal extremities, and mucosal surfaces; seen in patients with underlying SLE (Fig. 33.9).

Fig. 33.9 Bullous eruption of systemic lupus erythematosus. Vesicles and bullae due to autoantibodies against type VII collagen can develop in patients with systemic disease.

Acute Syndrome of Apoptotic Pan-Epidermolysis (ASAP)/Rowell’s Syndrome

• The term ASAP embraces various entities in which there is acute and widespread epidermal cleavage resulting from hyperacute apoptotic injury of the epidermis from various causes (e.g. drug-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis [TEN], TEN-like GVHD, and TEN-like ACLE).

• Rowell’s syndrome and TEN-like ACLE are thought to occur along a spectrum of ASAP, with the former representing a less severe erythema multiforme major-like presentation in the setting of lupus and the latter a potentially life-threatening TEN-like presentation in the setting of ACLE (Fig. 33.10).

Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus: Nonspecific Lesions

• A variety of cutaneous lesions not entirely specific to LE may be seen, signaling not only internal organ involvement (SLE) but also increased systemic disease activity (see Table 33.1).

Vascular Lesions and the Antiphospholipid Antibody Syndrome (APL)

• Vascular lesions and APL are common in patients with LE, especially those with SLE (see Table 33.1).

• Approximately one-third of APL cases occur in the setting of lupus (see Chapter 18); compared to primary APL, these patients are more likely to have arthritis, livedo reticularis (LR), and cytopenias.

• Patients with LE and APL may benefit from antimalarial therapy.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)

• The organ systems most commonly involved are the joints, skin, hematologic, lungs, kidneys, and CNS, which in large part are reflected in the ACR criteria for SLE diagnosis (see Table 33.2); however, this list is not exhaustive and clinical judgment is required.

• In individual patients it is often only one or a few organs that are significantly affected.

• ACLE is the specific CLE variant most closely associated with SLE, but patients with any type of CLE may develop internal involvement (SLE) (see Table 33.4).

• Indicators of an increased risk for SLE in patients presenting with CLE include fever, weight loss, fatigue, myalgia, lymphadenopathy, and nonspecific skin findings (see Table 33.1).

• The basic evaluation for SLE is highlighted in Table 33.3, and it is important to exclude drug-induced SLE (see Table 33.5).

• A negative ANA is helpful because it is highly unlikely that a patient with a negative ANA has SLE.

For further information see Ch. 41. From Dermatology, Third Edition.