Lumbar sympathetic blockade

Technique

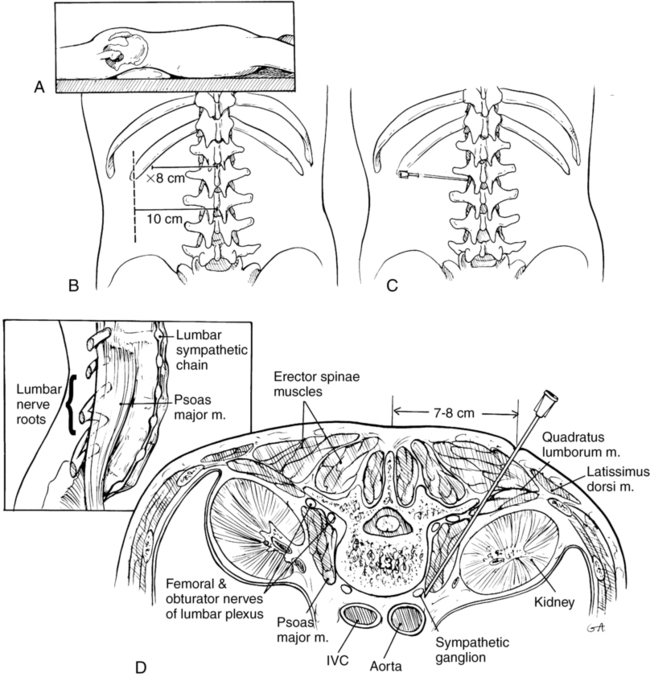

Lateral approach first described by reid

A 22-gauge 12-cm to 18-cm needle is advanced until it contacts the vertebral body at the cephalad portion of L3. The typical angle of insertion is 45 degrees, but this angle may be modified depending upon the patient’s body habitus. If bone is encountered soon after inserting the needle, the clinician has likely come into contact with a transverse process, and the needle trajectory should be modified cephalad or caudad to avoid contact with bone. If this occurs, the needle depth is noted, and the needle is retracted to skin level and redirected at a steeper angle under fluoroscopy to clear the lateral margin of the vertebra and position the tip at the anterolateral border of the vertebral body (Figure 219-1). The needle should be anterior to the psoas fascia. The needle is aspirated to verify extravascular position, taking into account the proximity of the aorta and vena cava. A small volume of iodinated contrast agent is injected, and spread should ideally be seen from L2 to L4. If spread is limited, additional needles can be placed at L2 and L4. Obtaining anteroposterior and lateral radiographic views helps to assess contrast spread, and, if striations (psoas stripe) are seen on fluoroscopy, the needle position may be too posterior.