62 Lumbar Radiculopathy

Clinical Presentation

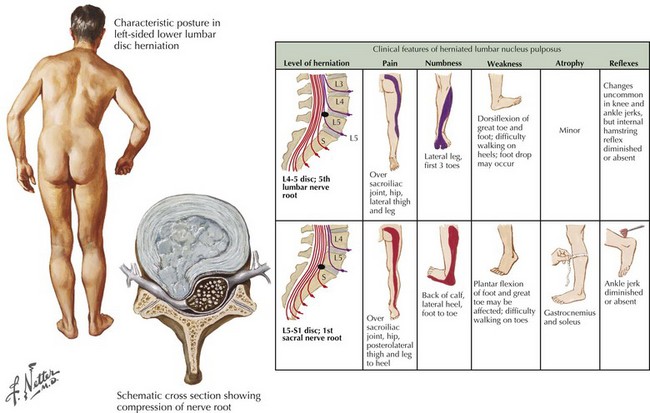

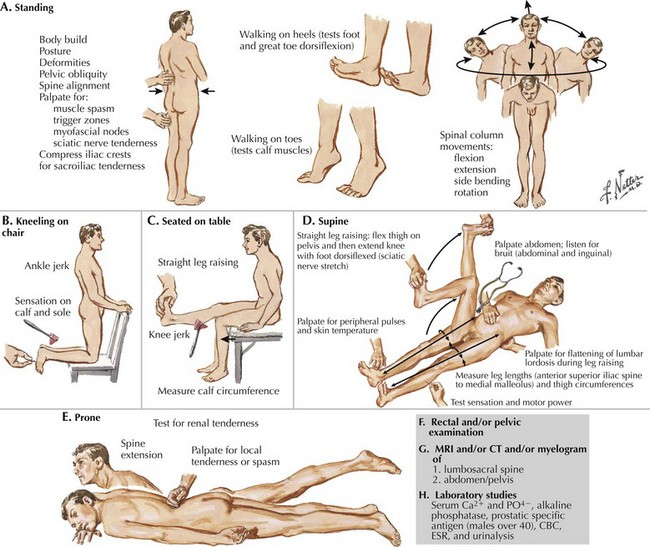

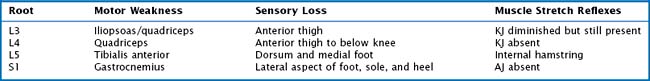

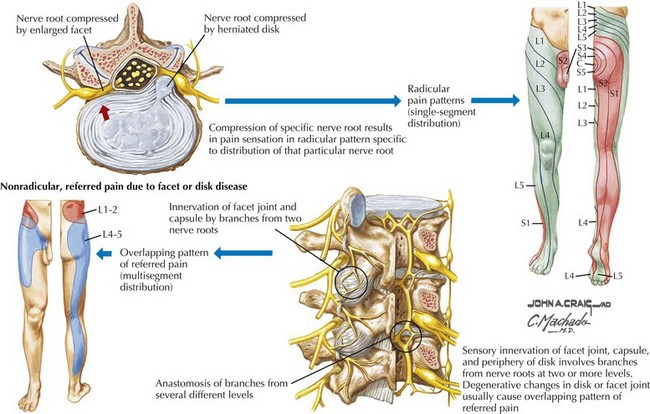

Sciatic pain may occur acutely or evolve more gradually; when the onset is sudden, it may be spontaneous or related to a specific incident, sometimes a seemingly trivial event, such as bending over to make a bed. The symptoms may be minor and clinically inconsequential or significant requiring urgent evaluation and treatment (Fig. 62-1). Depending on the specific nerve root involved, the pain may be classic sciatica with radiation down the posterior aspect of the leg into the foot, as is seen with compression of the L5 or S1 roots (Figs. 62-2 and 62-3). At higher levels, with L3 or L4 root compression, the pain may radiate to the anterior thigh. The clinical signs of lumbar radiculopathy are due to the specific level of involvement (Table 62-1), and the most common levels of nerve root irritation are L5 and S1 roots, followed less commonly by L4 and L3 roots. It is rare to have involvement of the higher roots (L1 and L2).

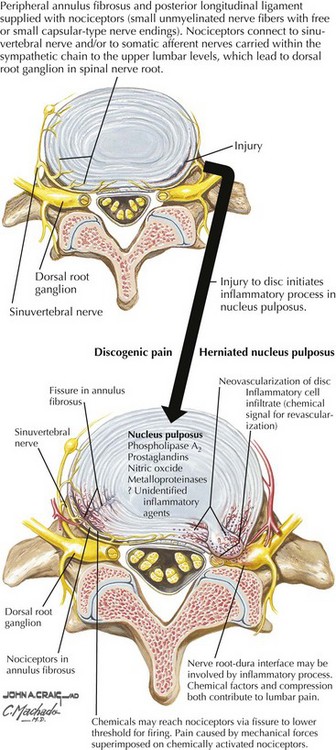

Etiology

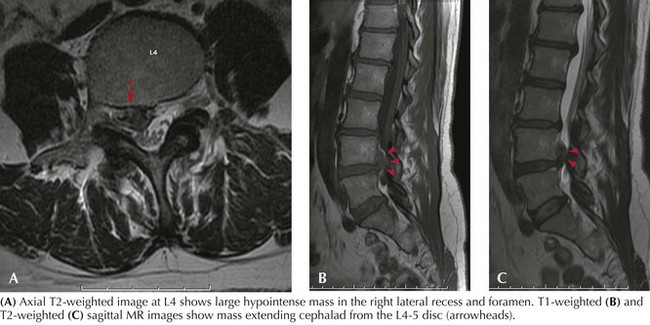

The most frequent cause of lumbar radiculopathy is a herniated lumbar disc, due to herniation of the nucleus pulposus, usually occurring with an equal frequency at the lowest two levels, L4–5 and L5–S1 (Figs. 62-4 and 62-5; see Fig. 62-1). Only ~5% of lumbar disc herniations occur at higher levels. Herniation is the last manifestation of disc degeneration that is an ongoing process in all humans. Hence, disc herniation is uncommon in youth, although occasionally teenagers and rarely toddlers have symptomatic herniations. Disc herniation occasionally occurs with spinal stenosis and may be the cause of rapid deterioration. Most lumbar radiculopathies are unilateral; bilateral sciatica has an ominous significance, suggesting compression of the cauda equina; these patients are at risk for loss of sphincter functions as well as sexual function in males. Early recognition is essential, as even after expeditious decompression, sphincter control and potency may not always return. Rarely spondylosis with foraminal encroachment resulting from disc degeneration may cause radiculopathy.

Differential Diagnosis

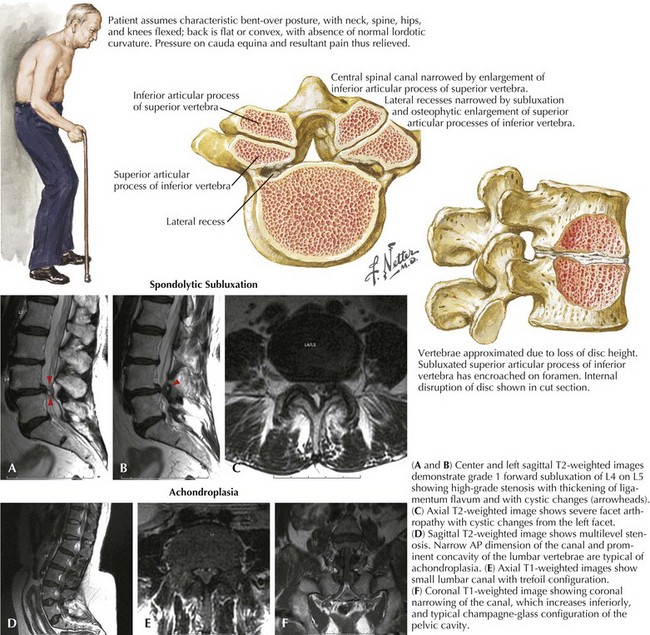

Spinal stenosis is becoming more prevalent with the increasingly aging population. It rarely occurs before age 60 years, although individuals with achondroplasia or other congenital processes, with narrow spinal canals caused by shortened pedicles, are predisposed to premature spinal stenosis. Spondylosis is the primary pathologic process, characterized by hypertrophy of the ligaments and facet joints (Fig. 62-6). Patients may develop single or multilevel spinal canal compression of the lumbosacral nerve roots; L3–4 and L4–5 interspaces are the most commonly affected levels; it is rare at L5–S1, unless there is subluxation of the vertebral bodies. Characteristically, the patient has a neurogenic claudication pain pattern mimicking arteriosclerotic occlusive (ASO) disease of the legs. Most individuals become symptomatic with standing or ambulating (Fig. 62-6). They are able to walk a set distance and then feel the need to sit; relief is usually rapid with sitting. Characteristically patients are more comfortable flexed at the waist; thus walking uphill may be easier than walking downhill, as spinal hyperextension associated with walking downhill may precipitate symptomatology. Patients may also be more comfortable leaning forward on a walker or grocery cart. Often the patient has a normal neurologic exam; occasionally, with long-standing symptomatic spinal stenosis, there may be neurologic deficits.

Spondylolisthesis, the anterior slippage of the superior vertebral body with respect to the inferior is another common cause of lumbar root compression, resulting in low back pain (Figs. 62-6A and B), radiculopathy symptoms, and sometimes cauda equina syndrome. The two common causes of spondylolisthesis involve spinal degenerative (spondylotic) changes and congenital defects of the vertebral pars interarticularis. Patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis tend to be older, whereas those with a pars defect usually present in their third or fourth decade with significant lumbar and root pain, usually related to postural change.

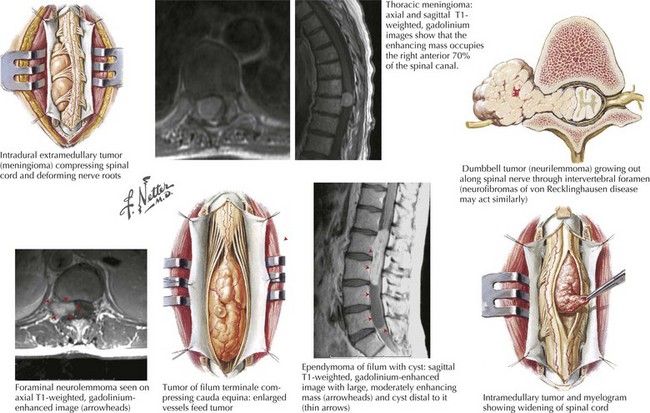

Neoplasms may be a cause of lumbosacral pain. Metastatic extradural cancers to the spine are the most common tumors. Primary bone tumors and intradural primary and metastatic tumors may also mimic discogenic disorders. The common cancers that metastasize include prostate, breast, lung, melanoma, and myeloma. Usually symptoms begin with spine pain that worsens gradually; root pain starts once neural elements become involved and may worsen rapidly. Evaluation and treatment in this situation is urgent, as recovery after treatment may not be complete. Schwannoma, meningioma, myxopapillary ependymoma, and lipoma are the common lumbar spinal intradural tumors (Fig. 62-7). The symptoms of schwannoma, meningioma, and ependymoma are gradually progressive. Patients with a lipoma, a congenital tumor, may have a history of baseline neurologic deficits with a slow, later progression.

Diagnostic Approach

Lumbar spine plain radiographs, including lateral flexion and extension views, serve two purposes: the anatomy of the spine with its degenerative changes is demonstrated, as are subluxations and instability and destructive lesions in the vertebral bodies, and disc space can be seen. MRI is the primary spinal imaging modality (Figs. 62-5 and 62-6). Good-quality MRI demonstrates disc herniation or spinal stenosis and identifies the rare tumor or infection. However, on occasion, for technical reasons, MR imaging may not be successful; for example, the patient may have moved during imaging; obesity or claustrophobia may be other impediments. Myelogram with CT continues to be a valuable adjunct to the diagnostic repertoire, especially when MRI is contraindicated (e.g., pacemaker) or not tolerated. Myelography with water-soluble contrast, followed by axial CT scanning, can demonstrate nerve root filling or lack thereof with more clarity than MRI. Sagittal and coronal reconstructions of CT data give excellent additional information. Electrodiagnostic studies are invaluable in those situations where data from imaging are difficult to interpret or where other superimposed conditions, for example polyneuropathy, coexist.

Treatment

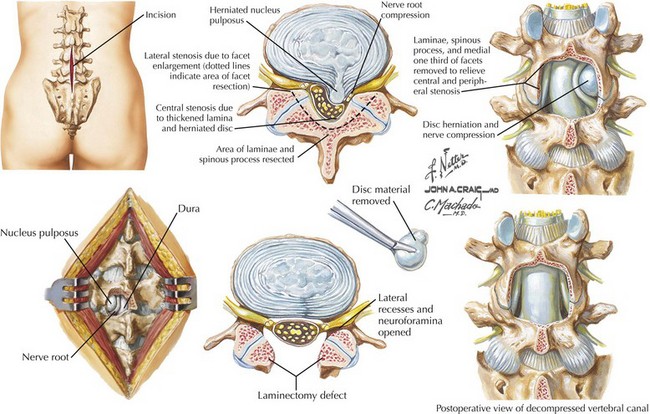

When acute symptoms do not improve, or the chronic degenerative disc-related pain persists, surgery is an option (Fig. 62-8). An important indication for surgery is the presence of a significant persistent neurologic deficit such as foot drop. However, severe or chronic unrelenting nerve root pain that disrupts a patient’s life is a common reason to proceed with nerve root decompression. When advising patients who are making decisions about surgery, they should be clear that postponing surgery would not place them in neurologic jeopardy, but that the discomfort will likely persist. Surgical goals for patients with degenerative disease or disc rupture relate to the pain’s origin. If the patient has root pain with corresponding root compression on imaging, the root or roots should be decompressed, and the herniated disc or synovial cyst removed. Surgery for an extruded disc requires removal of the extruded fragment with freeing of the compressed nerve root. With this technique, >90% of patients obtain symptomatic relief.

Berven S, Tay BB, Colman W, Hu SS. The lumbar zygapophyseal (facet) joints: a role in the pathogenesis of spinal pain syndromes and degenerative spondylolisthesis. Semin Neurol. 2002 Jun;22(2):187-196.

Binder DK, Schmidt MH, Weinstein PR. Lumbar spinal stenosis. Semin Neurol. 2002 Jun;22(2):157-166.

Katz JN, Dalgas M, Stucki G, et al. Degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Diagnostic value of the history and physical examination. Arthritis Rheum. 1995 Sep;38(9):1236-1241.

Schultz IZ, Crook JM, Berkowitz J, et al. Biopsychosocial multivariate predictive model of occupational low back disability. Spine. 2002 Dec 1;27(23):2720-2725.

Storm PB, Chou D, Tamargo RJ. Lumbar spinal stenosis, cauda equina syndrome, and multiple lumbosacral radiculopathies. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2002 Aug;13(3):713-733. ix

Winstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al. Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disk herniation: the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) a randomized trial. JAMA. 2006 Nov 22;296(20):2441-2450.