72 Lower Extremity Venous Ultrasonography

• Lower extremity ultrasound is the primary modality used to diagnose or exclude deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

• Clinician-performed bedside ultrasound can be accurate in detecting DVT when compared with radiology-performed examination.

• Two-point compression lower extremity ultrasound is a simplified approach that consists of compression of the common femoral vessels in the groin and the popliteal vessels in the popliteal fossa.

• Compressibility of veins via gray-scale B-mode ultrasound is the most important criterion for assessing DVT.

• Current practice guidelines recommend that proximal lower extremity ultrasound be repeated in 5 to 7 days after an initial negative two-point compression result to rule out propagation of unseen distal DVT.

Epidemiology

About 250,000 cases of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) are diagnosed each year. Failure to recognize and appropriately manage DVT can increase risk for the development of postthrombotic syndrome (disabling leg symptoms caused by venous reflux or ulceration) or pulmonary embolism (PE).1–4

DVT may develop in the lower or upper extremities. Although up to 18% are located in the upper extremities,5 the majority arise from the lower extremities. In the lower extremities, DVT is referred to as proximal when it is found in the popliteal veins or higher and as distal when it is located in the calf.

Perspective

Unfortunately, the diagnosis of DVT cannot be made on clinical signs and symptoms alone. The location of swelling and pain does not correlate with the location or extent of the clot, and symptoms localized to the calf may have an etiology in more proximal veins.6 Clinical signs have been analyzed statistically and found to be of little value in reliably determining the presence or absence of DVT.7 The differential diagnosis for leg pain and swelling includes lymphedema, chronic venous insufficiency, infection (cellulitis), aneurysm, pseudoaneurysm, Baker cyst, and other musculoskeletal causes. Diagnosis of DVT depends on the clinician’s pretest probability assessment and a combination of several noninvasive diagnostic tools (lower extremity ultrasound, D-dimer, or both). The exact diagnostic path or algorithm pursued depends somewhat on local availability and expertise. When available, lower extremity ultrasound is the primary modality used to diagnose or exclude DVT. The lower extremity ultrasound may be a proximal lower extremity examination, a whole-leg examination, or an abbreviated, two-point compression examination. If proximal lower extremity ultrasound is performed, current practice guidelines recommend that ultrasound of the proximal veins be repeated 5 to 7 days after an initial negative result to safely exclude clinically suspected DVT.8,9 This recommendation stems from the observation that up to 20% of cases of distal DVT may propagate into the proximal veins.10,11 A systematic review and metaanalysis published in 2010 found that after a negative whole-leg study, anticoagulation may be withheld safely without the need for a repeated ultrasound examination.12

Despite the numerous benefits of lower extremity sonography, many emergency providers continue to be unable to obtain lower extremity ultrasound after hours, on weekends, and on holidays. Clinician-performed two-point compression lower extremity ultrasound is now considered an appropriate method for assessing lower extremity DVT in the emergency department (ED) and is one of the 11 core emergency ultrasound applications.13,14 Emergency providers who perform two-point compression lower extremity sonography have demonstrated scan times of less than 4 minutes per patient and time savings of more than 2 hours in terms of time to patient disposition.15,16 When ultrasound is not available, providers may be forced to administer low-molecular-weight heparin and either keep the patient in the ED overnight or coordinate an outpatient study for the patient the following day. Although the risk for bleeding in these situations is low, boarding the patient in the ED or relying on patient-initiated follow-up is less than ideal. Given ever-increasing patient volumes and ED crowding, the value of clinician-performed two-point compression lower extremity ultrasound cannot be overstated.

Evidence-Based Review

Radiology-performed lower extremity duplex ultrasound has reported sensitivities of 91% to 96% and specificities of 98% to 100%.17,18 Multiple studies have demonstrated that clinician-performed two-point compression bedside ultrasound can be accurate in detecting DVT when compared with radiology-performed examinations.19–22 In a systematic review, Burnside et al. found an overall sensitivity of 95% and specificity of 96% for detection of lower extremity DVT by emergency physician–performed ultrasound.19 The authors caution that the six studies included in their analysis were limited by small sample size and by emergency physicians with high levels of ultrasonographic expertise, thus leaving their estimates at risk for being overly optimistic. A prospective study by Kline et al. in the same year assessed a more diverse range of clinician sonographers with more limited training in ultrasonography and found a sensitivity of 70% and specificity of 89%.20 They concluded that ultrasound performed by providers with limited training in compression ultrasonography of the lower extremity had intermediate diagnostic accuracy that may be improved by pretest probability assessment. A more recent prospective study by Crisp et al. included a large, heterogeneous group of emergency providers with variable levels of ultrasonographic experience but found the test results to be similar to those from the Burnside review with a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 99%.21

It is important to note that clinician-performed lower extremity sonography focuses on compressibility and typically does not include color flow Doppler or pulsed wave spectral Doppler beyond its use to localize or distinguish between vessels. Compressibility of veins with gray-scale B-mode ultrasound is the most important criterion and is widely accepted as being highly accurate.7 Color flow Doppler and pulsed wave spectral Doppler provide additional information and may be particularly useful when uncertainty exists or when assessing for pelvic DVT. Even though Doppler imaging has utility, it can be limited by the following: nonocclusive thrombus, the presence of collateral flow, and sonographer skill. Some studies have found that Doppler adds little to the information obtained by compression ultrasound for the detection of proximal DVT.22 In a prospective study by Biondetti et al., vein compressibility alone was compared with contrast-enhanced venography and found to have an overall sensitivity of 87% and a specificity of 100%.23 Because six of the seven false-negative examinations resulted from isolated distal DVT, the sensitivity of compression-only ultrasound for detecting proximal DVT was noted to be 98%. It is reasonable that clinician-performed lower extremity ultrasound studies consist only of compression.

Two-Point Compression Versus Whole-Leg Color Duplex Ultrasound

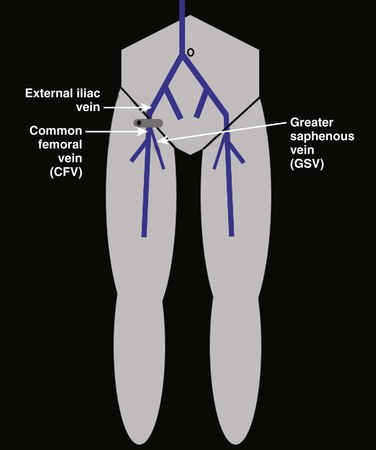

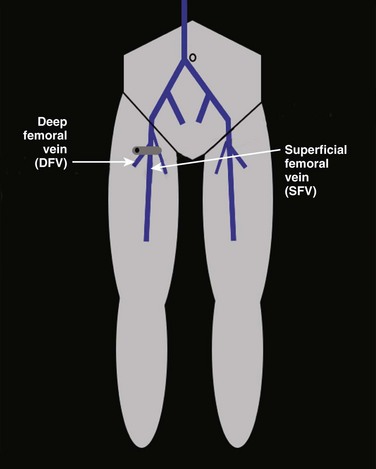

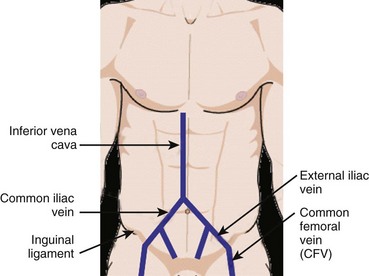

Two-point compression lower extremity ultrasound is a simplified approach that consists of compression of the common femoral vessels in the groin and the popliteal vessels in the popliteal fossa. The concept behind this abbreviated approach stems from the idea that clot usually involves multiple or whole venous segments. Several studies have shown that few cases of proximal DVT occur without involving either the common femoral vein (CFV) or the popliteal vein (PV), or both, and that isolated thrombus in the superficial femoral vein (SFV) is rare.24–27 In a study of limited compression ultrasound in patients with symptomatic DVT, Pezzullo et al. found a 54% reduction in examination time (9.7 minutes) while still maintaining high accuracy and patient safety.26 To the contrary, Frederick et al. prospectively studied 721 symptomatic patients and determined after 755 examinations that DVT limited to a single vein occurs with sufficient frequency that the lower extremity ultrasound cannot be abbreviated without resultant loss of diagnostic accuracy.28 To that end, in a retrospective study of 2704 lower extremity ultrasound examinations, Maki et al. found that acute DVT was isolated to the SFV in 22.3% of patients with DVT.29 They concluded that abbreviated imaging studies that evaluate only the CFV and PV could fail to detect up to 20% of proximal DVT and recommended interrogation of the SFV. The question of whether two-point compression can be performed in place of full-length examination remains controversial. In clinical situations in which radiology-performed, whole-leg sonography is not available, there is little controversy; clinicians should proceed with performing two-point compression lower extremity ultrasound. One solution to the vexing problem of missed SFV clots is to perform “two-region” compression ultrasound—that is, perform compression in the groin region from the greater saphenous junction through the bifurcation of the superficial and deep femoral veins and perform compression in the popliteal region from the PV to the trifurcation of the distal calf veins. This “two-region” approach has not been studied as a specific technique, although previous research would seem to support it as a compromise approach.

The value of whole-leg color duplex ultrasound is dependent on the significance of identifying distal DVT. The clinical relevance plus need to treat distal DVT is a controversial topic that continues to be debated. Proponents of full-length lower extremity examination point to a randomized trial by Lagerstedt et al. in which the usefulness of long-term anticoagulation (for 3 months) was assessed in patients with distal DVT. The authors found that those who did not receive long-term anticoagulation therapy had a significantly higher recurrence rate than those who did (8 of 28 patients versus 0 of 23 patients; P < .01).30 This study suggests that calf vein thrombi are important, should be sought in symptomatic patients, and when found, should be treated with long-term anticoagulation. Although the American College of Chest Physicians is in agreement with these findings,31 there is no universally accepted consensus on the management of distal DVT.32 Proponents of full-length examination often point to literature in which a proximal progression rate of up to 20% has been observed.10,11 Righini et al. contend that there is considerable uncertainty over the natural history of distal DVT and, in particular, over the rate of extension to proximal veins.33 The authors argue that if identifying and treating distal DVT do not improve patient outcomes, whole-leg color duplex ultrasound is of less clinical utility. Previous trials have demonstrated that it is safe to withhold anticoagulation in patients with suspected venous thrombosis and negative serial proximal ultrasound results even though some patients have calf vein thrombi.34 In a more recent, prospective, randomized multicenter study, Bernardi et al. compared serial two-point ultrasonography plus D-dimer testing with whole-leg color-coded Doppler ultrasonography for diagnosing suspected symptomatic DVT.35 Although the two-point protocol missed 65 cases of isolated calf DVT, the long-term outcomes for the two groups were similar, thus suggesting that searching for distal clots may be unnecessary.

One Leg Versus Both Legs

The question of whether lower extremity ultrasound examination should include only the symptomatic extremity or both lower extremities is a controversial topic. Proponents of scanning both legs point to literature demonstrating that unsuspected contralateral DVT and bilateral DVT are not uncommon and occur in up to 30% of cases.36,37 By interrogating both legs, a baseline study for future comparison can be obtained that may help differentiate acute from chronic venous thrombosis. Opponents of the bilateral lower extremity approach point to literature that describes the likelihood of finding clot solely in the asymptomatic leg to be as low as 0% to 1%.38 A retrospective study by Strothman et al. found that unilateral scanning would decrease examination times by 21% and could potentially increase total reimbursement for symptomatic venous scans by 9% when compared with routine bilateral duplex scanning.37 Supporters of single-leg studies note that treatment of DVT is typically the same regardless of whether DVT is found to be unilateral or bilateral. Because treatment with systemic anticoagulation is not altered and the potential for significant time and cost savings is real, many question the necessity of bilateral lower extremity imaging in all patients. As per the American College of Radiology–American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (ACR-AIUM) practice guidelines for the performance of peripheral venous ultrasound examinations, compression sonography may be unilateral (depending on the patient’s signs and symptoms and the clinical indication), but spectral Doppler, when performed, must at a minimum include spectral waveforms from both lower extremities.39

How to Scan

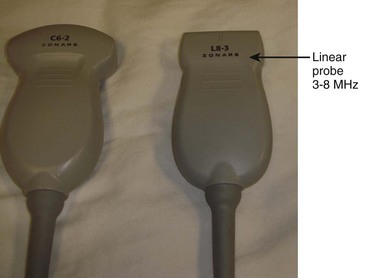

Lower extremity ultrasound is performed with the ultrasound machine positioned on the right side of the patient. Most ultrasound machines have different settings, and if available, the vascular or venous lower extremity setting should be selected. Room lighting should be decreased as much as possible to reduce the amount of gain required and help optimize the image. Typically, a linear probe with a frequency of 8 to 10 MHz is used (Fig. 72.1). For larger patients or those with significant edema, a probe with a lower frequency of 5 to 8 MHz may be used. Transducers with a curved footprint may make compression and assessment of vessel collapse more challenging. The probe should be held with the transducer marker pointing toward the patient’s right side or, in an equivalent manner, pointing toward the sonographer’s left side. The patient is positioned in the supine position with the head of the bed elevated 30 to 45 degrees, or alternatively, the head of the bed may be elevated in the reverse Trendelenburg position. Placing the patient in this position distends the lower extremity vessels and allows easier visualization and assessment. Color flow Doppler and pulsed wave spectral Doppler may be used to help distinguish or localize vessels when visualization through soft tissue is poor. The depth and focal zones should be adjusted accordingly to optimize the image.

Fig. 72.1 Linear probe with a frequency of 3 to 8 MHz.

Compression with a curved footprint transducer may be more challenging.

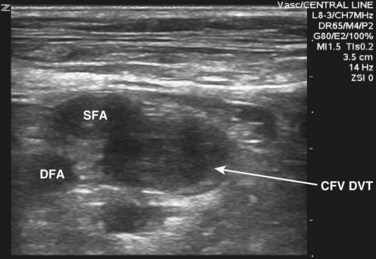

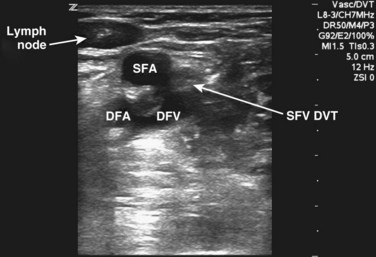

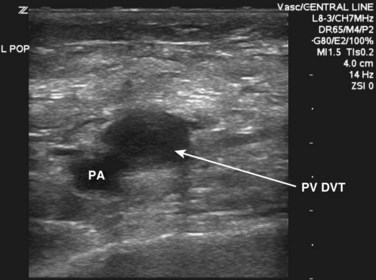

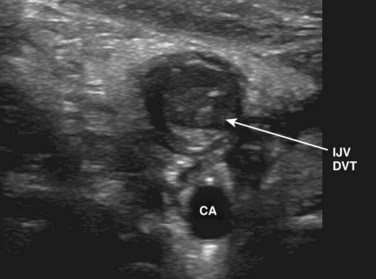

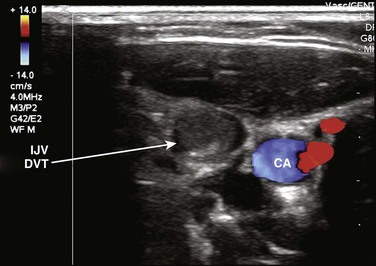

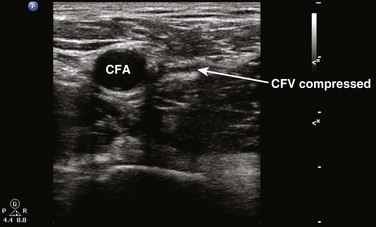

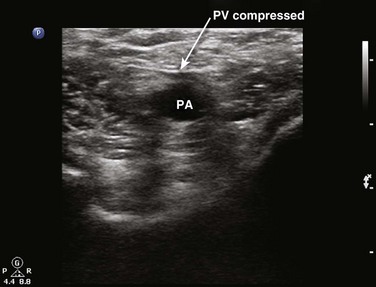

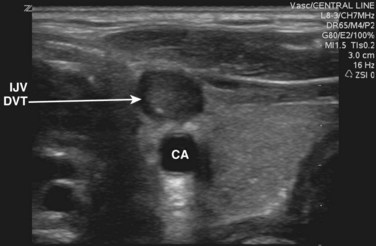

Compressibility is determined by applying direct pressure over the vein with the probe and assessing for coaptation of the vessel walls. It is important to note that firm pressure is often required and that the appropriate amount of downward pressure is typically achieved when the walls of the adjacent artery begin to deform. Compressibility is normal when coaptation of the vessel walls and complete obliteration of the intravascular space are seen. Anything short of this is concerning for DVT. With the amount of pressure required, some have questioned whether lower extremity ultrasound could potentially dislodge a thrombus and result in PE. Only one case report of PE resulting from compression sonography has been published.40 In general, compression sonography is regarded as safe, and gentle compression is advised. In situations in which thrombus can be directly visualized or is noted to be free floating, compression is not generally indicated. Another key point is the importance of applying pressure evenly and not at an angle; otherwise, the probe may roll off the vessel. A frequent initial challenge of performing lower extremity ultrasound is keeping the vessel in the middle of the viewing screen as pressure is applied. The probe is marched one probe width or approximately 1 to 2 cm at a time down the lower extremity. Acute DVT is diagnosed when the vein is found to be noncompressible. In some instances, thrombus may be directly visualized, but it is important to note that acute DVT tends to be less echogenic than chronic thrombus (Figs. 72.2 to 72.6). Acute DVT may also expand the vessel lumen or appear as a color void on color flow Doppler (Fig. 72.7).

Fig. 72.6 Noncompressible and hyperechoic deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in the internal jugular vein (IJV).

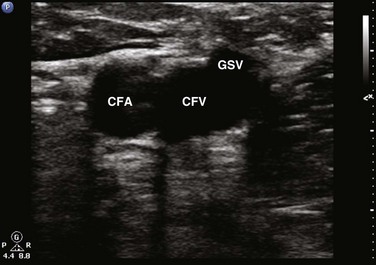

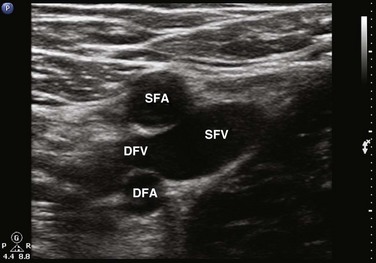

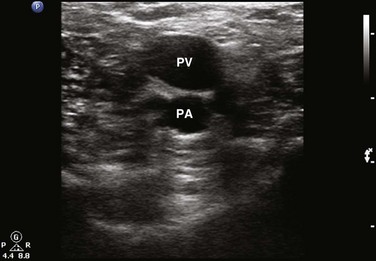

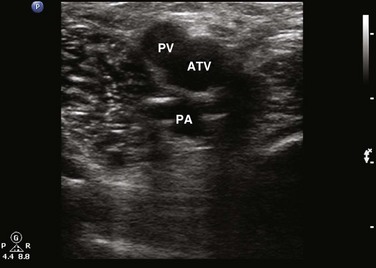

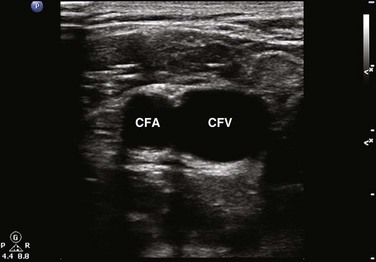

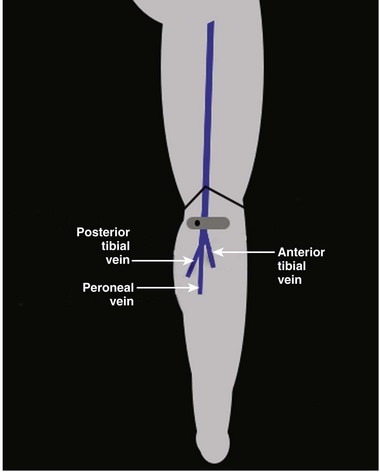

Compression sonography of the lower extremity begins just below the inguinal ligament, where the CFV is identified medial to the common femoral artery (Figs. 72.8 to 72.10). Within a few centimeters below the inguinal ligament, the most proximal branch of the CFV may be seen—the greater saphenous vein (GSV). The GSV runs medial and superficial as the probe is moved caudad away from the inguinal ligament (Figs. 72.11 and 72.12). Compression of the proximal GSV at its junction with the CFV is important because thrombus in this location is considered DVT and requires treatment. As the probe is marched caudad, the CFV then divides into the SFV and the deep femoral vein (DFV) (Figs. 72.13 and 72.14). It is important to recognize that the SFV is part of the deep venous system and not a superficial vein despite its name. There is considerable duplication of the lower extremity venous system, with multiple femoral veins occurring at a frequency of up to 20% to 30%.7,41 Compression sonography of the first few centimeters of the SFV and DFV should be performed, and once completed, the scan then proceeds down behind the knee in the popliteal fossa. To obtain access to the popliteal fossa, the lower extremity is flexed and externally rotated. Alternatively, the patient may be positioned in either a decubitus position with the study side up or in a prone position with the knee flexed 20 to 30 degrees. The PV is more posterior than the popliteal artery. Because the probe is placed posteriorly in the popliteal fossa, the PV appears more superficial on the viewing screen (i.e., at the top in the near field) (Figs. 72.15 to 72.17). The probe is placed behind the knee, high in the popliteal fossa, and compression is performed. The probe is then marched caudad along the PV until it trifurcates into the anterior tibial vein, posterior tibial vein, and peroneal vein (Fig. 72.18). It is important to scan the most proximal portions of these calf veins because thrombus in any of these locations is considered DVT and warrants anticoagulation. Although the venous system is relatively straightforward in the proximal end of the lower extremity, there is considerable variability below the popliteal fossa and in the calf. As per the ACR-AIUM practice guidelines, interrogation of the calf veins is not required.39 Even with the most careful and detailed examination of the calf veins it can be difficult to be certain that all of the possibly duplicated veins are free of thrombus.

Fig. 72.8 Compression sonography of the lower extremity begins just below the inguinal ligament at the CFV.

Fig. 72.9 Right lower extremity.

The common femoral vein (CFV) is identified medial to the common femoral artery (CFA).

Fig. 72.15 The popliteal vein divides into the anterior tibial vein, peroneal vein, and posterior tibial vein.

How to Incorporate into Practice

Clinician-performed lower extremity ultrasound can be performed in any patient with suspected DVT. As stated previously, the diagnosis of DVT depends on pretest probability assessment and a combination of several noninvasive diagnostic tools. In a certain subset of patients, D-dimer combined with clinical assessment may be used to eliminate or safely reduce the number of patients needing further noninvasive testing.32,42 Even with the use of such algorithms, D-dimer testing can exclude only less than half of patients with suspected DVT.43 With focused education and training,14 emergency providers may perform lower extremity ultrasound accurately and safely integrate bedside sonography into their specific DVT evaluation algorithms. Providers must remember that current practice guidelines recommend that proximal lower extremity ultrasound be repeated in 5 to 7 days after an initial negative result.8,9 Emergency providers should recognize that patient follow-up can be an issue and limitation. In a prospective observational study assessing patient follow-up after negative lower extremity bedside ultrasound, McIlrath et al. found that only 28% of patients obtained a follow-up ultrasound examination to rule out propagation of unseen distal DVT.44

American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine, American College of Radiology, Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound. Practice guideline for the performance of peripheral venous ultrasound. J Ultrasound Med. 2011;30:143–150.

Bernardi E, Camporese G, Buller HR, et al. Serial 2-point ultrasonography plus D-dimer vs whole-leg color-coded Doppler ultrasonography for diagnosing suspected symptomatic deep venous thrombosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300:1653–1659.

Burnside PR, Brown MD, Kline JA. Systematic review of emergency clinician–performed ultrasound for deep venous thrombosis. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:493–498.

Crisp JG, Lovato LM, Jang TB. Compression ultrasonography of the lower extremity with portable vascular ultrasonography can accurately detect deep vein thrombosis in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:601–610.

Dean AJ, Ku BS. Deep venous thrombosis. Hoffman B, ed. Ultrasound guide for emergency physicians. 2008. Accessed 20.04.12 http://www.sonoguide.com/dvt.html

Johnson SA, Stevens SM, Woller SC, et al. Risk of deep venous thrombosis following a single negative whole-leg compression ultrasound: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303:438–445.

1 Anderson FA, Wheeler HB, Goldberg RJ, et al. A population-based perspective of the incidence and case-fatality rates of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:933–938.

2 Gillum RF. Pulmonary embolism and thrombophlebitis in the United States. Am Heart J. 1987;114:1262–1264.

3 Trottier SJ, Todi S, Veremakis C. Validation of an inexpensive B-mode ultrasound device for detection of deep vein thrombosis. Chest. 1996;110:1547–1550.

4 Calder KK, Herbert M, Henderson SO. The mortality of untreated pulmonary embolism in emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45:302–310.

5 Mustafa S, Stein PD, Patel KC, et al. Upper extremity deep venous thrombosis. Chest. 2003;123:1953–1956.

6 Hirsh J, Hull RD. Venous thromboembolism: natural history, diagnosis, and management. In: Hirsh J, Hull RD. Diagnosis of venous thrombosis. Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC Press; 1987:23–28.

7 Cronan JJ. Venous thromboembolic disease: the role of US. Radiology. 1993;186:619–630.

8 Kearon C, Julian JA, Newman TE, et al. Non-invasive diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:663–677.

9 Qaseem A, Snow V, Barry P, et al. Joint American Academy of Family Physicians/American College of Physicians Panel on Deep Venous Thrombosis/Pulmonary Embolism. Current diagnosis of venous thromboembolism in primary care. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:454–458.

10 Birdwell BG, Raskob GE, Whitsett TL, et al. The clinical validity of normal compression ultrasonography in outpatients suspected of having deep venous thrombosis. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:1–7.

11 Fraser JD, Anderson DR. Venous protocols, techniques, and interpretations of the upper and lower extremities. Radiol Clin North Am. 2004;42:279–296.

12 Johnson SA, Stevens SM, Woller SC, et al. Risk of deep venous thrombosis following a single negative whole-leg compression ultrasound: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303:438–445.

13 American College of Emergency Physicians. Emergency ultrasound imaging compendium. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:487–510.

14 American College of Emergency Physicians. Policy statement: emergency ultrasound guidelines. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:550–570.

15 Blaivas M, Lambert MJ, Harwod RA, et al. Lower-extremity Doppler for deep venous thrombosis—can emergency physicians be accurate and fast? Acad Emerg Med. 2007;7:120–126.

16 Theodoro D, Blaivas M, Duggal S, et al. Real time B-mode ultrasound in the ED saves time in the diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Am J Emerg Med. 2004;22:197–200.

17 Lensing AWA, Prandoni P, Brandjes D, et al. Detection of deep vein thrombosis by real-time B-mode ultrasonography. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:342–345.

18 Gaitini D. Current approaches and controversial issues in the diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis via duplex Doppler ultrasound. J Clin Ultrasound. 2006;34:289–297.

19 Burnside PR, Brown MD, Kline JA. Systematic review of emergency clinician–performed ultrasound for deep venous thrombosis. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:493–498.

20 Kline JA, O’Malley PM, Tayal VS, et al. Emergency clinician–performed compression ultrasonography for deep venous thrombosis of the lower extremity. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:437–445.

21 Crisp JG, Lovato LM, Jang TB. Compression ultrasonography of the lower extremity with portable vascular ultrasonography can accurately detect deep vein thrombosis in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:601–610.

22 Lensing AWA, Doris CI, McGrath FP, et al. A comparison of compression ultrasound with color Doppler ultrasound for the diagnosis of symptomless postoperative deep vein thrombosis. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:765–768.

23 Biondetti PR, Vigo M, Tomasella G, et al. Diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis of the legs: accuracy of ultrasonography using vein compression. Radiol Med. 1990;80:463–468.

24 Cogo A, Lensing AW, Prandoni P, et al. Distribution of thrombosis in patients with symptomatic deep vein thrombosis. Implications for simplifying the diagnostic process with compression ultrasound. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:2777–2780.

25 Lansing AW, Hirsh J, Buller H. Diagnosis of venous thrombosis. In: Colman RW, Marder VJ, Clowes AW, et al. Hemostasis and thrombosis: basic principles. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 2001:1305.

26 Pezzullo JA, Perkins AB, Cronan JJ. Symptomatic deep venous thrombosis: diagnosis with limited compression US. Radiology. 1996;198:67–70.

27 Vogel P, Laing FC, Jeffrey RB, Jr., et al. Deep venous thrombosis of the lower extremity: US evaluation. Radiology. 1987;163:747–751.

28 Frederick MG, Hertzber BS, Kliewer MA, et al. Can the US examination for lower extremity deep venous thrombosis be abbreviated? A prospective study of 755 examinations. Radiology. 1996;199:45–47.

29 Maki DD, Kumar N, Nguyen B, et al. Distribution of thrombi in acute lower extremity deep venous thrombosis: implications for sonography and CT and MR venography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175:1299–1301.

30 Lagerstedt CI, Olsson CG, Fagher BO, et al. Need for long term anticoagulant treatment in symptomatic calf-vein thrombosis. Lancet. 1985;2:515–518.

31 Buller HR, Agnelli G, Hull RD, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for venous thromboembolic disease: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest. 126, 2004. 401S–28S

32 Ginsberg JS. Management of venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1816–1828.

33 Righini M, Paris S, Le Gal G, et al. Clinical relevance of distal deep vein thrombosis. Review of the literature data. Thromb Haemost. 2006;95:56–64.

34 Heijboer H, Büller HR, Lensing AWA, et al. A comparison of real-time compression ultrasonography with impedance plethysmography for the diagnosis of deep-vein thrombosis in symptomatic outpatients. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1365–1369.

35 Bernardi E, Camporese G, Buller HR, et al. Serial 2-point ultrasonography plus D-dimer vs whole-leg color-coded Doppler ultrasonography for diagnosing suspected symptomatic deep venous thrombosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300:1653–1659.

36 Naidich JB, Torre JR, Pellerito JS, et al. Suspected deep venous thrombosis: is US of both legs necessary? Radiology. 1996;200:429–431.

37 Strothman G, Blebea J, Fowl RJ, et al. Contralateral duplex scanning for deep venous thrombosis is unnecessary in patients with symptoms. J Vasc Surg. 1995;22:543–547.

38 Cronan JJ. Controversies in venous ultrasound. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 1997;18:33–38.

39 American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine, American College of Radiology, Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound. Practice guideline for the performance of peripheral venous ultrasound. J Ultrasound Med. 2011;30:143–150.

40 Perlin SJ. Pulmonary embolism during compression US of the lower extremity. Radiology. 1992;184:165–166.

41 Quinlan DJ, Alikhan R, Gishen P, et al. Variations in lower limb venous anatomy: implications for US diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis. Radiology. 2003;228:443–448.

42 Fraser JD, Anderson DR. Venous protocols, techniques, and interpretations of the upper and lower extremities. Radiol Clin North Am. 2004;42:279–296.

43 Stein PD, Hull RD, Patel KC, et al. D-dimer for the exclusion of acute venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:589–602.

44 McIlrath ST, Blaivas M, Lyon M. Patient follow-up after negative lower extremity bedside ultrasound for deep venous thrombosis in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:325–358.