Part 1: Liver178

18.1 Inflammation, fibrosis, cirrhosis and liver failure178

18.2 Alcohol- and drug-related liver disease181

18.3 Genetic, metabolic and vascular liver disease182

18.4 Liver tumours183

The liver performs many varied and vital functions. These include: the metabolism of protein, carbohydrate and fat; synthesis of proteins (including albumin, α1-antitrypsin, transferrin and coagulation factors); detoxification of waste products and ingested chemicals; and participation in the reticuloendothelial system. Chronic liver disease, the causes and consequences of which are discussed in this chapter, most frequently results from viral or alcohol-induced injury. Genetic, autoimmune and vascular diseases also affect the liver. Primary hepatocellular carcinoma is uncommon in the UK but is very common in countries with high rates of hepatitis B infection. The liver is a very common site for metastatic malignancy.

The biliary system functions include digestion of dietary fat and excretion of certain metabolites via the bile. While gall bladder stones and inflammation are very common in the Western world, congenital biliary atresia and malignant disease are unusual but clinically important conditions.

The exocrine pancreas produces digestive enzymes, including lipases, amylases and trypsin. These enzymes have a role in pancreatitis, a disease that is usually precipitated by alcohol ingestion or gallstones. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is a major cause of cancer mortality.

Part 1: Liver

You should:

• understand the definition, causes and clinical consequences of cirrhosis

• know the natural history of hepatitis B and C infections

• know the pathological effects of alcohol on the liver

• understand how therapeutic drugs can cause liver disease

• understand the range of viral, genetic and autoimmune diseases that can cause chronic hepatitis

• know the epidemiology and pathology of hepatocellular carcinoma.

18.1. Inflammation, fibrosis, cirrhosis and liver failure

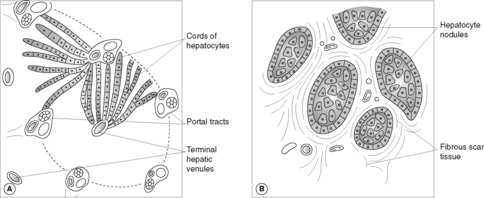

The clinical effects of cellular injury in the liver depend on the extent of cell death and the duration of the insult. For example, infection with hepatitis A virus may cause minimal asymptomatic disease, clinically apparent acute hepatitis with jaundice or, very rarely, acute liver failure (Box 25). In virtually every case, liver mass and architecture will be restored once the transient infection is cleared, and there is no residual hepatic damage. However, chronic inflammation in the liver can result in extensive fibrous tissue formation. Scarring may link portal tracts and central veins. Bands of fibrous tissue entrap regenerating nodules of hepatocytes, causing liver cirrhosis (Figure 49). Cirrhosis is the end stage of chronic inflammatory liver disease from numerous causes, including:

• alcohol

• chronic viral hepatitis (B and C)

• biliary disease (primary and secondary biliary cirrhosis)

• haemochromatosis

• idiopathic.

Box 25

Hepatic failure

Jaundice

Encephalopathy

• drowsiness, confusion, coma

• coarse hand tremor (‘liver flap’)

• fetor hepaticus

Hepatorenal syndrome (renal impairment secondary to liver failure)

Ascites/oedema

Chronic liver disease

Bruising

Gynaecomastia

Testicular atrophy

Palmar erythema

Clubbing

Dupuytren’s contracture (alcoholic cirrhosis)

Xanthomas (primary biliary cirrhosis)

Spider angiomas (spider naevi)

Ascites/oedema

Hypoalbuminaemia

Raised liver enzymes, coagulopathy, hyponatraemia

Raised serum ammonia in liver failure

Cirrhosis

Cirrhosis is a diffuse process and the damage is usually irreversible. The scarring disrupts and impairs blood flow through the liver, elevating the portal venous pressure (portal hypertension). As a consequence, blood flow increasingly bypasses the liver and flows through lower resistance vessels that communicate between the portal and systemic circulations. These anastomoses arise at four main sites:

• gastro-oesophageal junction (oesophageal varices)

• rectum

• retroperitoneum

• anterior abdominal wall (caput medusae).

There are two serious consequences of this vascular shunting:

• life-threatening haemorrhage from rupture of oesophageal varices

• impaired detoxification of noxious chemicals (e.g. ammonia), contributing to hepatic encephalopathy, coma and death.

Portal hypertension also causes splenomegaly and contributes to the development of ascites. Portal hypertension can be caused by other lesions that obstruct hepatic blood flow in the absence of cirrhosis, such as portal vein thrombosis and Budd–Chiari syndrome (see Section 18.3).

Cirrhosis is associated with development of hepatocellular carcinoma, although the degree of risk varies with the underlying disease.

Liver failure

Liver failure can be acute or chronic, and results when hepatic functional impairment is extreme. Mortality exceeds 70%. It is often precipitated by an event such as gastrointestinal haemorrhage or infection in a patient with chronic liver disease. Acute liver failure is uncommon, but may follow viral infection, drug exposure (e.g. paracetamol overdose, halothane), toxin damage (carbon tetrachloride), acute fatty liver of pregnancy and Reye’s syndrome (Section 18.3). In acute liver failure without pre-existing hepatic disease, there is extensive liver necrosis with shrinkage of the organ, and clinical features of hepatic failure – clotting deficiencies, jaundice, hepatic encephalopathy – developing over 2–3weeks. Massive liver destruction may prove fatal without transplantation, or cause irregular scarring in survivors.

Infectious hepatitis

Viral infection of the liver has various clinical manifestations, according to the specific agent involved:

• asymptomatic subclinical infection with complete resolution

• acute hepatitis

• chronic hepatitis

• asymptomatic carrier state

• hepatic failure (acute or chronic)

• cirrhosis

• hepatocellular carcinoma.

Acute hepatitis

In acute viral hepatitis (Box 26) there may be isolated liver cell necrosis or more severe bridging necrosis between portal tracts and central veins. Portal tracts are inflamed and there are increased numbers of Kupffer cells (sinusoidal macrophages). Swelling, necrosis and regeneration of hepatocytes produces architectural distortion called lobular disarray. All of these changes can revert to normal if infection is cleared.

Box 26

• Symptoms can include fever, fatigue, nausea, anorexia and right upper quadrant pain.

• Mild hepatomegaly may be detected on examination.

• Liver function tests (LFTs) are abnormal, with raised serum liver enzymes.

• If there is conjugated hyperbilirubinaemia, jaundice develops.

• Increased urinary bilirubin excretion produces dark urine, whereas decreased biliary excretion results in pale stools.

• Bile salt retention in the skin causes itching.

Chronic hepatitis

Chronic hepatitis is defined as abnormal LFTs and/or clinical evidence of continuing hepatic inflammation for >6months. The severity of inflammation varies within and between individual cases over time. Bile duct injury, fatty change, portal tract lymphoid aggregates and lobular inflammation are typical features of hepatitis C. Hepatocytes infected with hepatitis B may show ‘ground glass’ pink (eosinophilic) cytoplasm. The fibrosis and hepatocyte regeneration associated with chronic inflammatory damage may develop into cirrhosis.

Chronic hepatitis is not only due to viral infection – drugs, autoimmune disease and certain genetic disorders (see later) can cause very similar histological changes. Reaching the correct diagnosis requires consideration of all the clinical, serological, biochemical and pathological findings.

Carrier state

Disease carriers harbour persistent asymptomatic infection; they may be entirely healthy or have covert subclinical chronic liver disease. A carrier can pass infective virus on to non-immune contacts. Hepatitis B, C and D infections can produce a carrier state.

Hepatic failure, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma

These have been discussed above. Within the family of specific hepatitis viruses (Table 30), hepatitis B and C are the clinically most important causes.

| Hepatic virus | Nature of virus | Mode of spread | Clinical disease |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Single-stranded RNA virus | Faecal–oral spread from contaminated food and water, especially seafood | Usually self-limiting acute infection |

| Acute liver failure occurs in <1% | |||

| No chronic disease | |||

| No carrier state | |||

| B | Double-stranded DNA virus | Vertical (mother to fetus), sexual contact, blood transfusion, intravenous drug misuse | Very high rate of carrier state if infected in early life, with frequent chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Risk of chronic disease and malignancy is less if infection is acquired in adult life | |||

| C | Single-stranded RNA virus | Blood transfusion (patients with haemophilia) and inoculation (intravenous drug misuse) | Up to 85% develop chronic hepatitis; up to 50% of these progress to cirrhosis ± hepatocellular carcinoma ± hepatic failure |

| D | Defective RNA virus only infective in association with HBV | Parenteral | Can co-infect with HBV (usually recover normally, but risk of severe acute hepatitis is increased) or super-infect a HBV chronic carrier, with greatly increased risk of chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis |

| E | Single-stranded RNA virus | Faecal–oral spread from contaminated water | Usually self-limiting but 20% mortality rate in pregnant women |

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B infection occurs worldwide, but is extremely common in southeast Asia, where the disease is frequently transmitted from mother to fetus. Exposure early in life creates a permanent carrier state in over 90% of patients. Infection in the UK is usually acquired in adult life, through sexual contact, infected needles (drug misusers and healthcare workers) or an unknown source. Needlestick injury from a hepatitis B carrier confers a 30% risk of infection. The virus is present in blood and body fluids during incubation (which can be up to 6months from inoculation) and during periods of acute liver inflammation. The viral antigens and host antibodies detected in the serum reflect the stage of disease and infectivity of the patient. Core antigen (HbcAg) and the related HBe antigen are infective. The presence of IgM anti-HBc indicates recent infection. As the time period from infection increases, the antibody class switches to IgG. Surface antigen (HbsAg) positivity indicates acute infection or carrier state. HbsAb appears late and indicates immunity.

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C prevalence is uncertain, but estimated at between 0.1% and 1% of the UK population. There is an estimated 3% risk of transmission from an infected needlestick injury. Acute infection is asymptomatic in the majority. HCV antibodies are found in many patients with previously unexplained cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver function tests characteristically fluctuate throughout the course of the disease, and HCV RNA is detectable despite anti-HCV antibodies (the latter do not appear to confer immunity). Liver damage in part appears immunologically mediated. Patients may benefit from immune modulation therapy with interferon. Selection for such treatment is based on histological assessment of the degree of active inflammatory damage and the extent of fibrosis in a liver biopsy specimen.

Other causes of infectious hepatitis include:

• bacterial – tuberculosis, leptospirosis

• viral – cytomegalovirus (CMV), infectious mononucleosis (EBV)

• parasitic – malaria, amoebiasis.

Hydatid disease

Hydatid disease is a systemic infection due to the canine tapeworm Echinococcus. Although uncommon in the UK, hydatid disease occurs worldwide and incidence is increased in sheep- and cattle-farming areas. The liver is frequently involved with formation of single or multiple infected cysts, causing mass effects. There is a risk of disease dissemination or fatal anaphylactic shock if the cyst contents are liberated and care must be taken during surgical removal.

Liver abscesses

Liver abscess is uncommon in the UK and is usually due to bacterial infection. Organisms reach the liver via the bloodstream, biliary system or direct spread. Abscesses can be single or multiple. Surgical drainage is usually necessary. Parasitic and protozoal abscesses are more common in the developing world.

Autoimmune hepatitis

Autoimmune liver disease typically occurs in young and middle-aged adult females. Patients have a chronic hepatitis, which clinically and histologically resembles viral hepatitis, but serological tests show raised serum IgG and specific autoantibodies. The latter include antinuclear antibodies (ANA), antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA), antismooth-muscle and antimicrosomal antibodies. There is often associated extrahepatic autoimmune disease such as thyroiditis or rheumatoid arthritis.

18.2. Alcohol- and drug-related liver disease

Alcohol misuse is the major cause of chronic liver disease in the UK. Excessive alcohol intake can cause:

• fatty change (steatosis)

• alcoholic hepatitis

• cirrhosis, ± hepatocellular carcinoma.

Fatty change

Fatty change is the accumulation of fat droplets within the cytoplasm of hepatocytes, usually as a single large vacuole (macrovesicular steatosis). The change occurs throughout the liver, and may develop in chronic alcohol misuse or following ‘binge’ drinking in non-habituated individuals. Fatty change is reversible over several days of abstinence, but with repeated attacks, fibrosis can develop.

Alcoholic hepatitis

In alcoholic hepatitis (steatohepatitis) fatty change is accompanied by acute inflammation, with neutrophil polymorph infiltration around degenerate and necrotic hepatocytes. Abnormal liver cells may contain condensed intracytoplasmic proteins, known as Mallory bodies. Alcoholic hepatitis is associated with developing liver fibrosis, which characteristically starts around centrilobular veins. Whereas simple fatty change usually produces no clinical symptoms, patients with alcoholic hepatitis present with right upper quadrant pain and jaundice. Either condition may cause hepatomegaly.

With or without recurrent attacks of alcoholic hepatitis, individuals who maintain a high regular alcohol intake over several years are at risk of progressive fibrosis, cirrhosis and liver failure. Women appear to be at greater risk with a relatively lower alcohol intake. Coexistent liver disease, particularly haemochromatosis and hepatitis C infection, can be important contributory factors in progression to cirrhosis. Current recommendations are for women to drink no more than 14 units of alcohol per week, and men fewer than 21 units. Moderate regular intake seems less harmful than erratic, heavy, binge drinking. Indeed, regular, low ethanol intake seems to have a protective influence in coronary heart disease.

Acute alcohol intoxication

Acute alcohol intoxication causes injury and death through accidents, hypoglycaemia, epilepsy and direct cerebral toxicity. Chronic alcohol misuse can result in pancreatitis, cardiomyopathy, physical dependence, malnutrition and neurological disease (Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome – confusion, ataxia and ocular disturbances due to thiamine deficiency; if untreated, severe, irreversible amnesia often results).

Hepatic fat accumulation is most frequently seen in association with ethanol but other causes include:

• non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (diabetes mellitus, obesity, drugs)

• hepatitis C infection

• drugs

• Reye’s syndrome

• acute fatty liver of pregnancy.

Drugs and the liver

Drugs can cause many morphological changes in the liver; more common examples are shown in Table 31. As the histological features often mimic endogenous liver disease a thorough clinical history is essential. Mechanisms of drug damage are:

• direct toxicity

• conversion of drug to active toxin by liver

• immune-mediated (e.g. drug causes autoantibody production).

| Liver lesion | Examples of drugs responsible |

|---|---|

| Fatty change | Methotrexate, tetracycline |

| Hepatocyte necrosis | Paracetamol, halothane, isoniazid |

| Hepatitis and fibrosis | Methotrexate, amiodarone |

| Granulomatous inflammation | Sulphonamide antibiotics |

| Cholestasis | Chlorpromazine, contraceptive pill |

| Veno-occlusive disease | Cytotoxic drugs |

| Venous thrombosis | Cytotoxic drugs, contraceptive pill |

| Hepatocellular adenoma | Contraceptive pill |

Drug damage may be predictable, occurring in any individual who ingests a large enough dose, or idiosyncratic (host dependent).

18.3. Genetic, metabolic and vascular liver disease

Haemochromatosis

Haemochromatosis is an autosomal recessive disease with excessive iron storage predominantly in the liver, pancreas, myocardium and synovial joints. The gene involved is on chromosome 6. The heterozygote rate is approximately 10% in the white UK population and the homozygote disease state is relatively common (0.5%). Gene testing can confirm suspected clinical cases of haemochromatosis and can be used to screen other family members for the disease. Men are affected more often than women, possibly due to the ameliorating effect of menstruation in reducing total body iron. Presentation is most frequent in middle-aged adults.

The typical clinical triad consists of cirrhosis, diabetes and skin pigmentation (‘bronze diabetes’). Depending on the stage of disease, liver biopsy in homozygotes shows fibrosis or cirrhosis with excess iron in hepatocytes and Kupffer cells (liver macrophages). Iron is present in the form of haemosiderin pigment and appears yellow-brown on histological examination. A special stain, known as Perl’s stain, gives a bright blue colour to iron deposits and this allows the degree of iron overload to be graded microscopically. Heterozygotes for the abnormal haemochromatosis gene also show increased hepatic iron storage but not sufficient to cause significant tissue damage. The liver shows little inflammation. Cirrhosis occurring in haemochromatosis carries a very high risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, which is the leading cause of death in these patients. Complications of diabetes or of cardiac involvement (arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy) may also prove fatal. Treatment with iron chelators and regular venesection in the precirrhotic phase is successful.

Secondary causes of hepatic iron overload include severe anaemia, repeated blood transfusions and excessive dietary intake linked to use of iron cooking utensils.

α1-Antitrypsin deficiency

α1-Antitrypsin deficiency is a rare autosomal recessive disease which causes emphysema (see Ch. 15) and hepatic cirrhosis. Liver biopsy shows variably sized, round intracytoplasmic globules of α1-antitrypsin within hepatocytes, demonstrated by diastase periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining (see Box 27). Depending on the exact nature of the allele mutation, α1-antitrypsin can present in neonates, children or adult life. In severe disease, liver transplantation is curative.

Box 27

Routine histology slides are stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Nuclei take up the blue haematoxylin stain while cytoplasmic components show variable pink–red colouration from the eosin. When required, additional stains can be used in any tissues to demonstrate specific cell components and infectious agents. Examples are:

• Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS): stains carbohydrates magenta pink; PAS will stain glycogen in many cell types. Additional treatment with a diastase enzyme (DPAS stain) removes glycogen reactivity but allows demonstration of: mucin in gland-derived tumours (adenocarcinomas); fungi; and intracellular accumulations, such as α1-antitrypsin.

• Perls’ stain: demonstrates iron, for example in haemochromatosis. It can distinguish haemosiderin (iron-containing) pigment from melanin, both of which appear brown on H&E staining.

• Congo red: stains amyloid deposits salmon pink in normal light. When viewed with polarised light, the amyloid appears light green. (See Ch. 13.)

• Ziehl–Neelsen (ZN): stains mycobacteria (acid fast bacilli).

• Giemsa’s: demonstrates Helicobacter pylori and Giardia organisms.

Wilson’s disease

Wilson’s disease is a rare autosomal recessive disorder of copper metabolism, which affects the liver, eye and brain. The incidence is approximately 1 : 200 000. There is a decrease in the serum copper-containing protein caeruloplasmin. Histological examination shows increased hepatic copper, often with quite marked chronic inflammation, fibrosis and fatty change. Presentation can be at any age but is often in adolescents or young adults. Extrahepatic manifestations include a parkinsonian movement disorder, psychiatric symptoms and iris abnormalities (Kayser–Fleischer rings; green-brown copper deposits). If diagnosed early enough, copper chelating drugs are effective. If cirrhosis intervenes, liver transplantation may be considered.

Reye’s syndrome

Reye’s syndrome is a rare metabolic liver disease, with fatty change and encephalopathy. Reye’s syndrome usually arises in young children following a viral illness. Most patients recover but occasionally fulminant liver failure or permanent neurological deficit results. Reye’s syndrome is a disease of mitochondrial metabolism and has been associated with aspirin use – because of this association, aspirin is usually contraindicated in children under 12years of age.

Vascular disease in the liver

Venous congestion

Venous congestion of the liver is very common in cardiac decompensation, both right sided and congestive (biventricular). Cut section of the liver at autopsy resembles the stippled appearance of the cut surface of a nutmeg, hence the pathologist’s descriptive phrase, ‘nutmeg liver’. This appearance results from more intense congestion of blood around centrilobular veins than around portal tracts. If there has been severe hypoperfusion of the liver, centrilobular necrosis can occur – this central perivenular area is more at risk of ischaemic damage than the better oxygenated periportal zone.

Portal vein thrombosis

Portal vein thrombosis is uncommon. It is associated with local sepsis, liver cirrhosis, malignancy, adjacent lymphadenopathy and the postoperative state. It may present with pain, ascites, oesophageal varices or bowel infarction.

Hepatic vein thrombosis (Budd–Chiari syndrome)

Hepatic vein thrombosis (Budd–Chiari syndrome) occurs in thrombotic conditions (post-partum, pregnancy, polycythaemia, oral contraceptives, malignancy). It can be acute and fatal or chronic. Membranous webs, presumably representing resolved thrombus, may be seen in hepatic veins and inferior vena cava.

Veno-occlusive disease

Veno-occlusive disease in the UK is seen in bone-marrow transplant recipients, as a result of initial chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Intra-hepatic veins are obliterated and there is a high mortality rate, up to 50%.

18.4. Liver tumours

Benign liver tumours

Benign liver tumours include haemangiomas and liver cell adenomas. The latter occur most commonly in women and are associated with oral contraceptive use. There is a risk of tumour rupture with intraperitoneal haemorrhage during pregnancy.

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is relatively rare in the UK but represents the commonest visceral carcinoma in countries endemic for viral hepatitis (Table 32). The distribution is linked to hepatitis B infection, especially if acquired by vertical transmission from mother. The incidence of HCC in the Western world is likely to rise in future years due to hepatitis C infection. In the UK over 85% of patients with HCC have cirrhosis (compared to 50% or less in endemic hepatitis B countries), and most patients are over 60. Aflatoxin is a chemical carcinogen associated with HCC. It is produced by the Aspergillus fungus growing on mouldy food materials, particularly peanuts.

| Incidence | <2% of UK cancers; commonest visceral cancer in parts of Far East with high hepatitis B prevalence |

| Risk factors | Cirrhosis; hepatitis B infection (especially vertical transmission); hepatitis C; aflatoxin exposure |

| Protective factors | Prevention of hepatitis B and C infection |

| Associated lesions | Chronic viral hepatitis, haemochromatosis, cirrhosis from other causes |

| Common clinical presentation | Abdominal pain or mass, malaise, weight loss |

| Raised serum α-fetoprotein on monitoring of high-risk patients | |

| Location | Single mass or multiple lesions anywhere in liver |

| Macroscopic appearance | Well-defined solid lesion(s) or diffusely infiltrating |

| Histological features | Varies from well-differentiated lesion resembling normal liver cell plates to anaplastic malignancy |

| Pattern of spread | Lymph nodes; vascular spread, bones, lung |

| Prognosis (per cent 5-year survival) | Death usual within 6months of diagnosis |

| Much better prognosis, 60%, for fibrolamellar variant (young adults, no cirrhosis and hepatitis B negative) |

The majority of patients with HCC have raised serum α-fetoprotein (AFP), although this is not a specific finding. AFP can be raised in yolk-sac tumours of testis and ovary, in cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis without tumour, and in early pregnancy (fetal neural tube defects also cause raised AFP levels in the mother). Patients usually die within a few months of diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma due to cachexia, gastrointestinal bleeding, liver failure or tumour rupture and haemorrhage.

Angiosarcoma

Angiosarcoma is a malignant vascular tumour associated with vinyl chloride and Thorotrast (a radiological contrast agent) exposure.

Metastatic malignancy

The liver is a very common site for secondary tumour spread. Breast, lung, colon and other gastrointestinal cancers metastasise most frequently, but virtually any primary site may seed to the liver. Metastases usually form multiple nodules, and may cause massive hepatomegaly.

Part 2: Biliary disease

18.5. Inflammatory and other non-neoplastic biliary disease

Ascending cholangitis

Ascending cholangitis is infection of the biliary tree, usually by Gram-negative gut bacteria. There is often a biliary stone or stricture causing obstruction and stasis, which predispose to infection.

Primary biliary cirrhosis

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is characterised by granulomatous inflammation and destruction of intrahepatic bile ducts. It is an autoimmune condition with female predominance, which peaks in middle age. Symptoms include itching, jaundice and xanthomas (the latter due to cholesterol retention). LFTs show a marked increase in alkaline phosphatase, and autoantibodies to mitochondria. PBC is associated with other autoimmune diseases including Sjögren’s syndrome, thyroiditis and rheumatoid arthritis. Some cases will progress to cirrhosis.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

Primary sclerosis cholangitis (PSC) describes chronic inflammation with obliterative fibrosis and segmental dilatation of intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts. As with other causes of bile duct damage, serum alkaline phosphatase is increased. Males are most frequently affected and 70% have coexistent ulcerative colitis. The aetiology of PSC is uncertain. Progressive bile duct obstruction leads to secondary biliary cirrhosis.

Secondary biliary cirrhosis

Secondary biliary cirrhosis follows prolonged extrahepatic biliary obstruction, most commonly due to gallstone impaction in the common bile duct.

Bile duct damage can also occur in viral hepatitis, drug injury and liver transplant rejection.

Gallstones

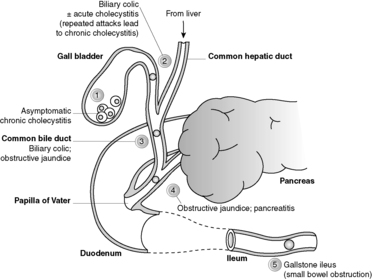

Gallstones occur in 20% of the adult population, but most do not cause symptoms. Female gender, increasing age, obesity, high-fat diet, pregnancy and oral contraceptive use are risk factors for the commonest type of stone (cholesterol rich). Stone formation requires supersaturation of cholesterol in bile. Biliary stasis – due to prolonged fasting, pregnancy, rapid weight loss or parenteral nutrition – is a promoting factor. Gallstones rich in pigment material develop in individuals with haemolytic anaemia. Biliary tract infection induces deconjugation of bilirubin, and the concentration of deconjugated bilirubin can exceed the low solubility. Clinical consequences of gallstones include biliary colic, obstructive jaundice and cholecystitis (Figure 50). Gallstones are a major cause of acute pancreatitis.

|

| Figure 50 |

Acute cholecystitis

Acute cholecystitis is usually caused by impaction of a stone in the neck of the gall bladder or the cystic duct. Bile outflow obstruction leads to chemical irritation of the gall bladder mucosa. With increasing distension and intraluminal pressure, blood flow to the gall bladder becomes compromised and ischaemia develops. The microscopic changes are typical of acute inflammation, with oedema and neutrophil polymorph infiltration. Complications of acute cholecystitis include:

• secondary bacterial infection

• gall bladder perforation and abscess formation

• rupture with peritonitis and fistula formation between gall bladder and bowel

• gall bladder infarction.

Recurrent attacks of acute cholecystitis can progress to chronic cholecystitis with fibrosis and mucosal outpouchings into the muscle layer (Rokitansky–Aschoff sinuses). Acute cholecystitis can also occur in the absence of calculi; precipitating factors include dehydration, gall bladder stasis, bile concentration (‘biliary sludge’) and bacterial infection. Such patients are often post operative or have suffered severe trauma, burns, sepsis and multiple organ failure.

Extrahepatic biliary atresia

Extrahepatic biliary atresia occurs 1 in 100 000 live births. Bile flow is completely obstructed due to destruction or absence of extrahepatic bile ducts in the neonatal period. The aetiology is uncertain – viral infection, genetic inheritance and anomalous embryological development have been suggested. Untreated, cirrhosis will develop within 6months. Surgical correction is not often possible as intra-hepatic ducts are also involved, and transplantation may offer the only chance of survival.

18.6. Bile duct and gall bladder neoplasia

Cholangiocarcinoma

Cholangiocarcinoma is a malignant tumour of either the intrahepatic or extrahepatic bile ducts. Associated factors include:

• Thorotrast

• liver fluke infection (Clonorchis sinensis)

• gallstones, ulcerative colitis and choledochal cysts (extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma).

Cholangiocarcinoma is usually a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, which induces a large amount of fibrous stroma (desmoplasia), imparting a very hard consistency to the tumour. Prognosis is poor due to local invasion and irresectability.

Carcinoma of the gall bladder

Carcinoma of the gall bladder is rare; it occurs in the elderly, usually associated with gallstones. Extensive local invasion is common at presentation and these unresectable tumours have a very poor prognosis. The vast majority are adenocarcinomas.

Part 3: Exocrine pancreas

18.7. Inflammatory disease of the pancreas

Inflammation of the pancreas can occur as a single acute attack or a chronic relapsing condition. Pancreatitis occurs most frequently in middle-aged men. Known precipitating factors of pancreatic inflammation include:

• Common:

• gallstones and biliary tract disease

• alcohol misuse (chronic pancreatitis, ?also acute).

• Rare:

• infection (mumps)

• drugs

• trauma

• shock

• localised surgical or endoscopic procedures

• congenital pancreatic abnormalities

• hypercalcaemia.

Pancreatic duct obstruction and direct injury to acinar cells seem to be involved in the initial insult. Damage to the exocrine pancreas liberates digestive enzymes – lipases, proteases and amylases – which increase the amount of tissue injury within the pancreas and adjacent organs. Raised serum amylase to greater than five times the normal is virtually diagnostic of acute pancreatitis. In severe acute haemorrhagic pancreatitis there is extensive blood vessel damage and abdominal fat necrosis. Systemic effects of enzyme release can include disseminated intravascular coagulation, adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and shock. Less serious complications are pancreatic abscess and pseudocyst formation. A pseudocyst is a collection of secretions within or outside the pancreas. The pseudocyst has a fibrous capsule but no epithelial lining. (True epithelial-lined pancreatic cysts occur in von Hippel–Lindau disease and adult polycystic kidney disease.)

Repeated, often mild, acute attacks lead to chronic pancreatitis, with marked scarring of the organ and loss of exocrine and endocrine function, with development of steatorrhoea and diabetes in severe cases. Pseudocysts are frequent in chronic pancreatitis. There is an increased risk of pancreatic carcinoma.

18.8. Neoplastic disease of the exocrine pancreas

Benign tumours of the pancreas are often cystic, and may be composed of mucinous or serous glandular epithelium. Malignant pancreatic tumours – adenocarcinomas – almost always derive from the ductal epithelium. Most tumours arise in the proximal organ (Table 33), and cause localising symptoms due to obstruction at the ampulla of Vater or distal common bile duct. The prognosis is poor, death often occurring within months of diagnosis.

| Incidence | Common visceral cancer; middle-aged and older males, incidence increasing |

| Risk factors | Not well defined – ?smoking, previous gastric surgery, chronic pancreatitis (alcohol) |

| Protective factors | Not known |

| Associated lesions | – |

| Common clinical presentation | Abdominal and back pain, weight loss, jaundice |

| Migratory thrombophlebitis (10%) | |

| Location | 60% in head of pancreas, 20% diffusely involve gland |

| Macroscopic appearance | Hard grey/white mass |

| Histological features | Gland formation, with reactive, dense, fibrous tissue |

| Perineural invasion | |

| Pattern of spread | Extensive local spread to duodenum, bile duct, stomach, retroperitoneal organs, lymph nodes, liver |

| Prognosis (per cent 5-year survival) | Less than 5% |

Self-assessment: questions

True-false questions

1. The following diseases are associated with the development of cirrhosis:

a. hepatitis C

b. hepatitis A

c. haemochromatosis

d. haemolytic anaemia

e. alcoholic steatohepatitis

2. Acute liver failure typically occurs in:

a. paracetamol overdose

b. acute viral hepatitis

c. primary biliary cirrhosis

d. Reye’s syndrome

e. Budd–Chiari syndrome

3. Regarding hepatitis B:

a. acute infection is usually asymptomatic

b. infection early in life confers a higher risk of chronic carrier state

c. the source of infection is always identifiable

d. HbsAg detection in the blood indicates immunity

e. co-infection with HDV increases the risk of severe acute hepatitis

4. Complications of cirrhosis include:

a. gynaecomastia

b. hepatocellular carcinoma

c. renal failure

d. gastrointestinal haemorrhage

e. confusion

5. The following are correctly paired:

a. Wilson’s disease – abnormal lead metabolism

b. haemochromatosis – hepatocellular carcinoma

c. α1-Antitrypsin deficiency – bronchiectasis

d. Veno-occlusive disease – cytotoxic chemotherapy

e. angiosarcoma – vinyl chloride exposure

6. Pancreatic carcinoma:

a. is increasing in incidence

b. has a 5-year survival rate of 50%

c. often presents with painless jaundice

d. is usually surgically resectable at presentation

e. histologically is a squamous cell carcinoma

7. Concerning gallstones:

a. cholesterol is the most frequent stone component

b. most patients are symptomatic

c. they are associated with gall bladder adenocarcinoma

d. stones can develop following prolonged fasting

e. the incidence is increased in oral contraceptive users

8. The following are causes of extrahepatic bile duct obstruction:

a. biliary atresia

b. primary biliary cirrhosis

c. primary sclerosing cholangitis

d. gallstones

e. pancreatic adenocarcinoma

9. Acute cholecystitis:

a. can occur in the absence of gallstones

b. is characterised by lymphocytic infiltration of the gall bladder

c. can be complicated by fistula formation

d. frequently results in gall bladder infarction

e. is increased in incidence in postoperative patients

10. The following are associated with primary biliary cirrhosis:

a. xanthomas

b. raised serum antimitochondrial antibodies

c. rheumatoid arthritis

d. granulomatous inflammation of the portal tracts

e. decreased serum alkaline phosphatase

Case history questions

Case history 1

A 52-year-old woman presents with abdominal discomfort and increasing girth secondary to ascites. On examination there are additional signs of chronic liver disease.

1. What other physical signs of liver disease would you look for? What specific questions would you ask in the clinical history?

2. What further investigations would you consider?

3. What information might be provided by a liver biopsy?

4. What are the most important complications of cirrhosis?

Case history 2

You are an occupational health physician and a venesector asks you for advice after sustaining a needlestick injury. The healthcare worker has been immunised against hepatitis B but is anxious about contracting hepatitis C infection.

1. What information could you give regarding the incidence, rate of transmission and rate of progression of hepatitis C infection in this situation?

2. What measures should be taken to reduce the risk of healthcare personnel contracting hepatitis B and C?

Case history 3

A 44-year-old man is admitted to hospital with nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain radiating to the back. He admits to a high alcohol intake. The surgical registrar suspects acute pancreatitis and requests serum amylase, calcium, liver function tests and arterial blood gas measurement.

1. How will these investigations contribute to the patient management?

The patient is confirmed to have acute pancreatitis. He recovers with hospital treatment and is discharged home, but returns 2weeks later with further pain and vomiting. Ultrasound examination reveals a cystic mass.

2. What is the likely cause of the mass?

Viva questions

1. How would you classify tumours of the liver?

2. How does knowledge of the pathology of haemochromatosis help in the management of patients and their families?

Self-assessment: answers

True-false answers

1.

a. True.

b. False. There is no chronic infective state in hepatitis A.

c. True.

d. False.

e. True. If excess alcohol consumption continues.

2.

a. True.

b. True. Uncommon but can occur in hepatitis A (and E), very rare in B and C.

c. False. Liver failure develops chronically following cirrhosis in severe cases.

d. True.

e. True.

3.

a. True.

b. True.

c. False. Vertical transmission, sexual contact and inoculation of infected blood are the major methods of transmission but the actual source may not always be identifiable.

d. False. Hepatitis B surface antigen indicates acute infection or carrier state. HbsAb indicates immunity.

e. True. See Table 30.

4.

a. True. Probably due to altered oestrogen metabolism.

b. True.

c. True. Decompensated cirrhosis can lead to hepatorenal syndrome, in which renal failure occurs secondary to liver failure. The mechanism is thought to involve altered renal blood flow. Kidney dysfunction is reversible if the liver failure can be successfully treated.

d. True. Usually from oesophageal varices, an important complication.

e. True. If hepatic encephalopathy develops.

5.

a. False. Copper metabolism is deranged in Wilson’s disease.

b. True. There is a high risk of liver cancer in patients with haemochromatosis who develop cirrhosis.

c. False. The lung lesion present in α1-antitrypsin deficiency is emphysema.

d. True.

e. True.

6.

a. True.

b. False. Five-year survival is less than 5%.

c. True.

d. False.

e. False. Adenocarcinoma.

7.

a. True.

b. False. Many adults do not complain of symptoms related to their gallstones.

c. True. But the risk to individual patients is very low given the high prevalence of gallstones and rarity of gall bladder cancer.

d. True. Presumably due to increased bile concentration and cholesterol saturation.

e. True.

8.

a. True.

b. False. This disease is confined to intra-hepatic ducts.

c. True.

d. True.

e. True. Sixty per cent of pancreatic carcinomas arise in the head of the gland and can obstruct the distal common bile duct.

9.

a. True. But stones are present in >90% of cases, either in the gall bladder neck or cystic duct.

b. False. Neutrophil polymorphs are characteristic of acute inflammation.

c. True. Between the gall bladder and intestine, usually colon.

d. False. Ischaemic necrosis is a rare but serious complication leading to perforation and peritonitis.

e. True.

10.

a. True.

b. True.

c. True. There is an association between primary biliary cirrhosis and other autoimmune conditions.

d. True.

e. False. Alkaline phosphatase is raised in biliary tract damage, and may be the only abnormality in the liver function tests in primary biliary cirrhosis.

Case history answers

Case history 1

1. The signs of chronic liver disease are shown in Box 25 (page 179). Relevant information from the clinical history would include alcohol consumption (although patients may not give an honest answer!), family history of liver disease (which may point to an inherited disease), possible exposure to hepatitis B and C and any history of autoimmune disease. As many therapeutic drugs can damage the liver in numerous ways, a careful history of recent and long-term prescribed medications is often helpful.

2. Full investigation of chronic liver disease may include:

• liver function tests – liver enzymes released from damaged cells (γ-glutamyl transferase, aspartate aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase), and markers of synthetic function, such as albumin

• coagulation tests (international normalised ratio (INR))

• viral serology – hepatitis B and C (hepatitis A does not cause chronic disease)

• autoimmune screen – helpful for diagnosing primary biliary cirrhosis and autoimmune chronic hepatitis

• ultrasound – to assess liver size, texture (fatty change or cirrhosis) presence of masses/cysts and examine the biliary tree for dilatation (obstruction)

• gene analysis for haemochromatosis

• serum protein electrophoresis for α1-antitrypsin

• serum caeruloplasmin measurement (Wilson’s disease)

• liver biopsy.

3. Liver biopsy is an invasive procedure which can be helpful in the investigation of:

• unexplained hepatomegaly or abnormal liver function tests

• cirrhosis

• tumours (primary or metastatic)

• hepatic damage by medications – for example, methotrexate used in psoriasis

• assessing degree of inflammation and fibrosis in hepatitis C infection, in order to select patients for interferon therapy.

Percutaneous liver biopsy carries a very small risk of mortality but should not be undertaken in patients with abnormal clotting, obstructive jaundice or ascites. An alternative approach in high-risk patients is to perform a transjugular biopsy, approaching the liver through the inferior vena cava.

4. Important complications of cirrhosis are discussed in the text (Section 18.1) but include:

• haemorrhage from portal-systemic anastomoses, especially oesophageal varices

• hepatic encephalopathy

• development of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Case history 2

1. The incidence of hepatitis C in the UK is probably less than 1% of the general population but there are high-risk factors including intravenous drug misuse and blood transfusion prior to the introduction of hepatitis C screening of blood donations in 1991. There is an approximately 3% risk of contracting hepatitis C via a needlestick injury from an infected patient but the risk may vary according to the stage of the disease and the viral load as assessed by HCV RNA analysis using the polymerase chain reaction. The rate of progression to chronic hepatitis may be as high as 85% and up to 50% of these individuals may develop cirrhosis.

2. All healthcare workers potentially exposed to blood and body fluids should be immunised against hepatitis B for their own and their patients’ safety. There is no vaccination for hepatitis C, so minimising the risk of infection is vital, by wearing protective clothing including gloves and eye protection when appropriate. Open wounds must be fully covered with waterproof dressings. Any specimens of blood, body fluid or tissue sent to pathology laboratories with suspected or known infection risk must be clearly labelled as ‘high risk’ to protect staff – nurses, operating department assistants, porters, laboratory scientists and doctors – who may come into contact with the material. High-risk status applies to any material potentially infected by hepatitis B or C, HIV or tuberculosis. If you need advice, contact your hospital’s occupational health department.

Case history 3

1. The clinical history suggests an acute abdomen; the differential diagnosis would include acute pancreatitis, acute cholecystitis and a perforated peptic ulcer. Myocardial infarction must also be excluded. The investigations ordered would be appropriate to confirm a clinical diagnosis of acute pancreatitis and to assess the severity of the attack. Amylase is released from the inflamed pancreas and a serum rise to greater than five times the normal upper limit usually indicates acute pancreatitis. However, less severe elevation of serum amylase can occur with other conditions including cholecystitis and perforated peptic ulcer. Severe attacks of acute pancreatitis may be associated with decreased serum albumin and calcium, and a lowered arterial oxygen concentration. The mortality rate in poor prognosis cases exceeds 50%.

2. The likely cause is a pancreatic pseudocyst. If large, the cyst may require drainage by aspiration or surgical excision.

Viva answers

1. Comment: Remember in viva answers to be logical, structured and emphasise the more common conditions. In the UK, liver metastases are more common than primary tumours. You could classify primary intrahepatic tumours by their cell of origin. The list below is not exhaustive but would be appropriate for this question:

Benign neoplasms

• Epithelial: hepatocellular adenoma.

• Vascular (endothelium): haemangioma.

Primary liver malignancies

• Epithelial: hepatocellular carcinoma; cholangiocarcinoma (arising in intrahepatic bile ducts)

• Vascular (endothelium): angiosarcoma.

Secondary liver tumours

• From many sites, but particularly colon, upper gastrointestinal tract, breast and lung.

2. Comment: The question requires you to explain the clinical implications of the pathogenesis, genetics, incidence, progression and complications of haemochromatosis. Points to include are:

• mode of inheritance (autosomal recessive)

• heterozygote carrier and homozygote population frequencies

• subclinical disease in heterozygotes

• the opportunity for familial disease screening and early diagnosis through genetic testing

• prevention of serious complications, cirrhosis and liver cancer, by early treatment aimed at reducing body iron (venesection and chelating agents)

• role of liver biopsy in assessing stage and severity of disease, and response to treatment (reduction in hepatic iron stores and cessation of disease progression).